Caspar David Friedrich und die Vorboten der Romantik (Caspar David Friedrich and the Precursors of Romanticism)

Reviewed by Gregor WedekindGregor Wedekind

Professor of Modern Art, Department of Art History and Musicology

Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, Mainz

Email the author: gregor.wedekind[at]uni-mainz.de

Citation: Gregor Wedekind, exhibition review of Caspar David Friedrich und die Vorboten der Romantik (Caspar David Friedrich and the Precursors of Romanticism), Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.1.21.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Caspar David Friedrich und die Vorboten der Romantik (Caspar David Friedrich and the Precursors of Romanticism)

Museum Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt

April 2–July 2, 2023

Kunst Museum Winterthur, Winterthur

August 26–November 19, 2023

Catalogue:

Wolf Eiermann and David Schmidhauser, eds.,

Caspar David Friedrich und die Vorboten der Romantik (Caspar David Friedrich and the Precursors of Romanticism).

Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2023.

240 pp.; 150 color illus.; bibliography; notes.

CHF 48.00 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978–3–7774–4339–3

2024 marks the 250th anniversary of Caspar David Friedrich’s birth in Greifswald on September 5, 1774. This year will present an impressive array of events and publications in honor of the painter. In Germany, a total of eight special exhibitions will take place at five locations—Hamburg, Berlin, Dresden, Greifswald, and Weimar—followed by the first comprehensive exhibition dedicated to the artist in the US at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from February 7 to May 11, 2025. The appreciation of Friedrich as the main master of German Romanticism, which has been continually underway since the 1970s, and his international position as one of the great painters of the nineteenth century, are thus definitively established. The challenges posed by the anniversary year in terms of the availability of loans are easily imagined. Their availability is further restricted by Putin’s imperial war against Ukraine, which makes it currently impossible to borrow Friedrich’s works from Russian museums.

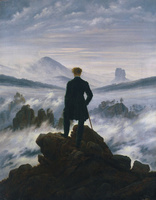

This situation was the reason why two other museums, the Museum Georg Schäfer in Schweinfurt and the Kunst Museum Winterthur, each of which owns a substantial collection of Friedrich’s works, joined forces. They shared a catalogue and a number of artworks in order to dedicate an exhibition to the forerunners of Romanticism in 2023, a prelude to the anniversary year. The intention was to show that Friedrich’s atmospheric landscape art had precursors and can be embedded in an art historical development that goes back to the seventeenth century. Since Schweinfurt and Winterthur have so many important works by Friedrich, essential to the exhibitions planned for 2024, they were able to acquire spectacular loans in turn. These include Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (fig. 1) and Meadows near Greifswald (1821–22) from the Hamburg Kunsthalle, The Watzmann (1824–25) and Moonrise by the Sea (1822) from the Berlin National Gallery, and The Ruins of Eldena Abbey in the Riesengebirge (fig. 2) from the Pomeranian State Museum in Greifswald. All of them are normally unavailable for loan but were presented first at the Museum Georg Schäfer and then at the Kunst Museum Winterthur.

While the exhibition in Schweinfurt was conceived as a series of consecutive rooms of different sizes and could therefore be experienced as a structured sequence, in Winterthur the museum’s attic offered only a single, sober, rectangular room. The massive suspended ceiling with its sloping panels created an oppressive effect. The entrance, located in the center of the hall, divided the exhibition into a right and a left side, but without giving the visitor any supplemental orientation. For further subdivision, three movable walls were installed across the room on each side. They provided both wall space and additional demarcation in their staggered arrangement. Even if the spatial conditions of the exhibition were not ideal, they had the advantage over the Schweinfurt venue of appearing much more compact. It was easier for the visitors to assess its size, encouraged visitors to move back and forth between the different sections, and, thanks to the open-plan layout, offered a variety of different views. The visitors were not so much guided as sent on a journey of discovery.

The color scheme in Winterthur was designed to impress: the partitions inserted into the room were kept in a vibrant, deep ultramarine blue (fig. 3). This was certainly intended to provide a color appropriate to Romanticism on the one hand, but also to show off the gold of the picture frames in a particularly brilliant way. Each wall was also dedicated to a single painting placed in the center, thus showcasing the first-class loans as precious masterpieces. The strong colors unintentionally contrasted with the unpretentiousness of Romantic art. On the light-colored sidewalls of the exhibition space, the paintings were hung in an orderly arrangement of fitting constellations.

Upon entering the exhibition space, visitors were greeted by two particularly spectacular loans on blue walls: to the right, The Ruins of Eldena Abbey in the Riesengebirge (see fig. 2), to the left the Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (see fig. 1). The Eldena referenced Friedrich’s birthplace of Greifswald and pointed to the focus on his biography in the right wing of the exhibition. Panels attached to the rear wall offered a chronology of Friedrich’s life and offered a series of keywords, each characteristic for his oeuvre and important for “German Romanticism.” This didactic material was visually complemented by a portrait of Friedrich at the age of around thirty-five by his painter friend Gerhard von Kügelgen (1772–1820; fig. 4). His head is almost completely enclosed by a flowing mutton chop beard, and his hair is combed over his forehead, inviting comparison with the heart-shaped face of a barn owl. This analogy is supported by the strong bridge of the nose, critically pursed lips, and the curved brow above the narrow and deep-set eyes, with their sharp, skeptically distant gaze. His face recalls Charles Le Brun’s comparisons of the faces of animals and humans and Johann Caspar Lavater’s physiognomic theories.

Visitors were thus introduced to a painter who was as proud as he was distant, giving them an idea of the philosophical seriousness of Friedrich’s artistic endeavors. Facing back towards the center of the hall, the iconic The Chalk Cliffs on Rügen (fig. 5) and Meadows near Greifswald (again referencing Friedrich’s birthplace) were hung on the backs of the partitions and had to be discovered within the exhibition route. The Chalk Cliffs was further deemphasized as a highlight by the fact that the exhibition title was displayed on the wall above the painting in large white letters. This disposition made the picture seem like nothing more than a poster image for the exhibition.

Apart from the initial space, written explanations were used with restraint in Winterthur. A panel entitled “Appreciation and Rediscovery” referred to the changing perceptions of Friedrich by his contemporaries and his “rediscovery” by the Norwegian art historian Andreas Aubert in the context of his studies on Johan Christian Clausen Dahl (1788–1857). Shortly thereafter, the Centennial Exhibition of German Art in Berlin in 1906 initiated his reappraisal in relation to French impressionism. One of its initiators was Julius Meier-Graefe, to whom Oskar Reinhart, the founder of the Winterthur Museum, had close ties. Meier-Graefe encouraged Reinhart to collect nineteenth-century German art, including Caspar David Friedrich.

After these introductory sections, a further panel on “Precursors of Romanticism” provided information about the exhibition’s specific aim to relate Friedrich to seventeenth-century Dutch landscape painting, eighteenth-century French landscape painting, and the local tradition of landscape established with the appointment of Adrian Zingg (1734–1816) to the Dresden Academy of Art in 1766. The exhibition did not content itself with bringing together a few capital Friedrich paintings but instead emphasized the heritage that enabled Friedrich’s achievement. This perspective helps visitors to understand a group of sepia works, created between 1801 and 1807, with which Friedrich established himself as an artist in Dresden and achieved his first successes in the art market and with critics. Although only a few of them were on display in Winterthur, they were shown alongside works by Zingg, who developed sepia into an artistic trademark in Dresden in the 1770s and 1780s (fig. 6). In other words, Friedrich was not only a pupil of the Dresden Landscape School in the literal sense—in 1798 he enrolled in the Dresden Academy’s register for some additional study in the “Kunstfach Landschaftsmalerey” (subject of landscape painting)—but also in his choice of sepia as a medium. One would have liked this to be examined in more detail and to have included works by Jacob Crescentius Seydelmann (1750–1829), the Dresden Academy professor and actual inventor of the technique that made Zingg and his school famous. However, Seydelmann is only mentioned once in the catalogue, without reference to existing research.[1]

The comparison of Zingg’s works with Friedrich’s shows that the latter developed his artistic practice in direct connection with the local tradition, whose pictorial type he adapted. At the same time, he used his engagement with this tradition to develop his own style and gain artistic individuality (fig. 7). Zingg’s sepias appear overloaded with detail and meaningful motifs, as well as entirely committed to the classical pictorial structure of foreground, middle ground, and background. In contrast, Friedrich simplifies, breaks up the spatial structure, reduces the composition to striking symmetries, and dramatizes the landscape through the abrupt confrontation of the near and the far.

These beginnings were preceded by other beginnings, which were also displayed in Winterthur but not given enough attention. Friedrich’s training at the Copenhagen Academy between 1794 and 1798 played virtually no role in the exhibition. Rather, it was assumed that it was only in Dresden that he turned his attention to the study of nature and, against this backdrop, to landscape painting and its European tradition. Two of the rare examples of oil painting in Friedrich’s early work, shortly before 1800, could be seen in the exhibition. One was The Oak Tree (1798; private collection, Lübeck). The attribution to Friedrich was not explained and treated only en passant in Detlev Stapf’s catalogue essay on Friedrich’s biography, where it is noted that the picture is a partial copy after a painting by Jens Juel (1745–1802) from around 1790. Juel was one of Friedrich’s teachers in Copenhagen. Are we supposed to imagine that Friedrich was occupied with copying after his former teacher at the time of his reorientation in the early Dresden period? The second painting in this category was Landscape with a Bare Tree from 1798–99 from the Galerie Neue Meister in Dresden (fig. 8). It is listed in Helmut Börsch-Supan’s and Karl Wilhelm Jähnig’s catalogue raisonné of 1973. There and in Winterthur, it serves as evidence of an early pictorial production in the footsteps of Jacob van Ruisdael (1628–82).

The formal and stylistic characteristics of both pictures are weakly developed. Are these the signs of an undeveloped epigone or an indication of a searching journey through styles and pictorial concepts? And why, if Friedrich was already capable of painting such landscapes in oil shortly before 1800, did he simply stop and only return to oil painting at the end of 1807? Not only do The Oak Tree and Landscape with a Bare Tree require further discussion as to whether they are by Friedrich’s hand, but also Marine with Ruined Temple (1802; private collection), which was attributed to Friedrich by Bettina Erche (an attribution that has so far been completely ignored by researchers following the publication of her article).[2] Similarly, the etching Landscape with Ruined Temple (1802; Herzog-August-Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel) has been conventionally assigned to Friedrich, but this needs to be questioned. A lot is still lying in the dark here.

The exhibition demonstrated throughout that questions of continuity and demarcation not only play a role in the beginnings of every artistic career, including Friedrich’s, but also run through his entire oeuvre. For example, it underlines Friedrich’s commitment to the Dutch tradition of marines and seascapes with the juxtaposition of Friedrich’s Sailing Ship (ca. 1815; Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, Chemnitz) and Aert van der Neer’s (1604–77) magnificent Canal Landscape in the Moonlight (after 1650; Museum Heylshof, Worms) at either end of one wall. Between them, seven of Friedrich’s seascapes were flanked by paintings by Jan van Goyen (1596–1656) in a beguiling arrangement. The group emphasized the depiction of light reflecting off the water and the sky, in particular the enchantment of the evening atmosphere and nocturnal moonrises. The juxtaposition with van Goyen was instructive. In the latter’s work (fig. 9), the sky takes up much more of the picture’s surface; by means of a very low horizon, it appears as an enormous dome, which is experienced as a space belonging to the viewer. Friedrich, on the other hand, is interested in both sky and sea, and begins the picture in the foreground, where the viewer is confronted with a proximate view of sandy shore, puddles, and shallows (fig. 10). The surface of the water extends up from the shore to a horizon that is further back and higher, thus making the distance appear much more remote and the space more extensive than in the van Goyen. The atmospheric and wistful stillness of his work strikes a distinctly different note from van Goyen’s harmonious interplay of nature and man in a bustling world. And in turn, the decidedly graphic qualities of a painting such as Harbor by Moonlight (fig. 11) drew attention to those of van Goyen.

So near, yet so far away: the phrase applies to painters who were both personally and artistically close to Friedrich, such as Dahl. Friends since 1818, they even shared an apartment at An der Elbe 33 in Dresden in 1823. In Winterthur, Dahl’s Evening Landscape with Shepherd (fig. 12) was shown next to the somewhat earlier The Evening by Friedrich (fig. 13). The comparison suggests itself because of the atmospheric light on the horizon and darkened foreground sinking into colorlessness, and also because of the rigid linearity of the trunks of the conifers. At the same time, the differences are striking. Whereas in Dahl’s work the depiction of the shepherd with his dog and herd of cattle suggests an unexceptional rural narrative, in Friedrich’s work we don’t know what the two figures dressed in black are doing in the dark forest, but their action—contemplating the evening light shining through between the trees—suggests a spiritual or aesthetic purpose. In Dahl’s work, the shepherd also adopts a contemplative stance, but it remains unclear whether his attention is focused on the evening light or on his flock. Where Dahl shows the view of the landscape extending into the depths of the picture, Friedrich erects a barrier in the pictorial space with the tree trunks. This focuses our attention on their view and therefore foregrounds their gaze, or the act of viewing. Linked to this is the special way in which Friedrich lends the light a visionary quality. This could also be observed in Winterthur by looking at examples from the eighteenth century of effective depictions of light, such as Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg’s (1740–1812) Nocturnal Scene with Soldiers at the Fire (fig. 14), which explores nocturnal illumination by comparing the brightly shining moon in the dark sky to the man-made light of the campfire—i.e., through islands of light in the dark. Friedrich’s Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon (fig. 15), on the other hand, like The Evening, leaves the group of people in darkness, appearing only as silhouettes or shadows against the night sky, illuminated by the moon in the depths of the picture. For Friedrich, light is always remote.

The Wanderer, with its view of majestic mountains, signaled the theme for an important section on the left side of the exhibition space: Friedrich’s participation in what might be termed Philhelvetism, or the emergence at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries of admiration for Switzerland, and particularly for its mountains as a natural source of emotion or inspiration. This section could rely on pictures from the museums’ own holdings, which were grouped around the Berlin loan of the The Watzmann from 1824–25, placed in the center of the rear wall on the left side of the room (fig. 16). It was accompanied on the left and right by two mountainscapes created at almost the same time: Joseph Anton Koch’s (1768–1839) The Wetterhorn with the Reichenbach Valley (1824; Kunst Museum Winterthur, Winterthur) and Carl Gustav Carus’s (1789–1869) The Sea of Ice near Chamonix (1825–27; Museum Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt).

Although Friedrich never travelled to Switzerland, he was clearly fascinated by the political and natural attributes of the alpine country. Promoted by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78), Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805), and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), the appearance of the country was conveyed to him through travelogues and Swiss landscape prints, for example those by Salomon Gessner (1730–88), but also through his friends Dahl and Carus. They, unlike him, had seen the Alps with their own eyes and captured them in drawings and paintings, which became the basis for Friedrich’s own Swiss mountain pictures. In addition, Dresden had its own “Alps” on its doorstep in the form of the so-called Sächsische Schweiz, which Zingg, a native Swiss, had already established as a destination and motif for painters. Friedrich’s conceptualization of the mountains as an artistic subject directly followed Zingg’s example. To these he added the Harz Mountains and the Riesengebirge, which he had also hiked. His translation of nature into landscape paintings was meticulously made on the basis of drawings done after nature, which were then freely combined to create complex compositions.

For The Watzmann he used not only a watercolor study by his pupil August Heinrich (1794–1822), but also his own sketches of rocks in the Harz Mountains and the Riesengebirge. The resulting visual exaggeration of the motif by means of a channeling of vision toward something high and far away contributes to the emotionally heightened visual experience of the viewer. In this way, Friedrich took up the existing traditions, altered or perfected them, and imbued many of his landscapes with a sense of utter desolation. Where Carus, for example, domesticates the phenomena of the enormous alpine mountain world with the fascinated gaze of a worshipper of mountains, Friedrich distances them from the viewer as a world in its own right, foreign and elusive.

Overall, both versions of this exhibition offered rich material. With its subtly balanced hanging and convincing groupings of paintings, the Winterthur version was more successful in enabling visitors to study general theses on the basis of individual cases. It visualized by comparison the intellectual, political, and artistic stakes of landscape painting in Europe from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. At the same time, the exhibition was a fine demonstration of the fact that it is not necessary to isolate or separate Friedrich from tradition in order to demonstrate the modernity of his work; on the contrary, it is only by examination and confrontation with his predecessors and contemporaries that the extent and originality of his artistic achievement become clear.

Notes

[1] See Werner Busch, “Caspar David Friedrichs frühe Sepien als Vorstufe der romantischen Landschaft,” in Wissenschaft, Sentiment und Geschäftssinn: Landschaft um 1800, ed. Roger Fayet, Regula Krähenbühl und Bernhard von Waldkirch (Zürich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2017), 118–50.

[2] Bettina Erche, “Marine mit Tempelruine—ein Frühwerk von Caspar David Friedrich aus dem Jahre 1802,” Städel-Jahrbuch, N.F. vol. 20 (2009): 237–52.