Louis Janmot: Le Poème de l’âme (Louis Janmot: The Poem of the Soul)

Reviewed by Jonathan P. RibnerJonathan P. Ribner

Associate Professor

Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University

Email the author: Jribner[at]bu.edu

Citation: Jonathan P. Ribner, exhibition review of Louis Janmot: Le Poème de l’âme (Louis Janmot: The Poem of the Soul), Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.1.19.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Louis Janmot: Le Poème de l’âme (Louis Janmot: The Poem of the Soul)

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

September 12, 2023–January 7, 2024

Catalogue:

Servane Dargnies-de Vitry and Stéphane Paccoud, with contributions by Isabelle Saint-Martin, Elena Marchetti, and Clément Paradis,

Louis Janmot: Le Poème de l’âme (Louis Janmot: The Poem of the Soul).

Paris: Musée d’Orsay, in association with In Fine éditions d’art, 2023.

192pp.; 4 b&w and 184 color illus.; bibliography; chronology; checklist; notes and references; index.

€ 35 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978–2–35433–368–3

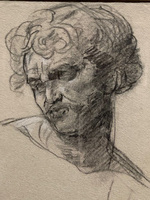

In 1832, the eighteen-year-old Louis Janmot (1814–92) was awarded the Laurier d’or (Golden Laurel) at Lyon’s École des Beaux-Arts for an arrestingly odd self-portrait (fig. 1).[1] If the sharp contour and mimetic specificity foretell that the artist would study under Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867), there is also evidence of a sensibility too idiosyncratic to ever be justly called ingriste. Hieratic frontality and a hint of androgyny speak of otherworldliness. And the close-fitting, square-collared garb is distinctly not of the painter’s time. These peculiarities and the unnerving intensity of the stare—as if Janmot is searching the mirror to glimpse his soul—are prophetic of the undertaking that would occupy forty-three years of this devout Catholic’s long career, Le Poème de l’âme (The Poem of the Soul; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon).

This was a project of dizzying ambition: an exposition of the soul’s advent, development, temptation, fall, and redemption represented in novel visual form and accompanied by 2,814 lines of Janmot’s own verse. Eighteen paintings (ca. 1836–54) were followed by a second cycle comprising sixteen large charcoal drawings (ca. 1856–79) that the artist considered complete works rather than preparatory studies. Two additional, unrealized cycles were planned. According to Janmot, these were to have represented “la vie active de l’âme sur la terre” (“the active life of the soul on earth”) and “sa vie active au delà du temps” (“its active life beyond time”).[2]

On April 1, 1854, Janmot exhibited the paintings in his Lyon studio. Between April 22 and June 7, he reexhibited them in Paris. Having garnered positive attention from critics Théophile Gautier (1811–72) and Alphonse de Calonne (1818–1902), the paintings were admitted to the Exposition Universelle of 1855 on the recommendation of Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863). The hanging and public response left Janmot bitterly disappointed. Located apart from the painting section, the canvases were hung with architectural drawings, at a height that prevented clear viewing. According to Charles Baudelaire (1821–67), they were “l’objet d’un auguste dédain” (“regarded with august contempt”).[3]

Le Poème de l’âme then descended into near oblivion despite the publication in 1881 (by the Auguste Théolier press in Saint-Étienne) of 400 copies of the thirty-four-poem text.[4] By subscription, readers could acquire an additional volume with carbon photographic reproductions of both cycles, printed in an edition of 160. Offered for sale as a single lot following Janmot’s death, the ensemble found no buyer. Rediscovery would be slow. In 1921, the Lyon Musée des Beaux-Arts declined to purchase the painted cycle due to cost and lack of space. That year, five of the works appeared in a Paris exhibition dedicated to the students of Ingres and organized by the Société de Saint-Jean; Maurice Denis (1870–1943) wrote of them admiringly. In 1948, René Jullian (1903–92), director of the Lyon Musée des Beaux-Arts, was offered the ensemble by the artist’s descendants on the condition that it be exhibited. Notwithstanding Jullian’s enthusiasm, spatial limitations blocked acquisition. Jullian exhibited both cycles at the museum in 1950; in 1955, they were gifted to the Faculté des Lettres of the Université de Lyon. Ten years later, the painted cycle was hung in the Faculté’s council room; the second cycle was transferred to the museum. After some of the paintings in the first cycle were vandalized during the political turbulence of May 1968, the paintings and drawings were given to the city of Lyon and entered the collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts. In 1973, both cycles were declared monuments historiques. The paintings and drawings were restored and exhibited at the museum in 1976; afterwards, the paintings remained on view. Renovation of the museum in 1998 yielded a gallery dedicated to the painted cycle; the drawings are too fragile for permanent display.

Visitors to the splendid exhibition Louis Janmot: Le Poème de l’âme at the Musée d’Orsay had a rare opportunity to view both cycles, last shown together in 2007.[5] The challenge of exhibiting thirty-four large pictures intended to be viewed consecutively was brilliantly met. Most of the components of Le Poème de l’âme hung on trios of freestanding, double-sided planar supports, whose stele form imparted a solemnity appropriate to the numinous aspect of the program (fig. 2). Evenly spaced to encourage study of individual works, the stelae were grouped so as to reveal counterpoint and continuity within subsections of each cycle. Views through gaps between the slabs piqued curiosity regarding the next stage of the itinerary. In the painted cycle, blue skies, green foliage, and translucent, white robes resonated with light gray surroundings. Dark gray supports provided an effective foil to the sepia and black charcoal drawings opening the second cycle (fig. 3). Toward the conclusion of the second cycle, the stelae again became light gray. Throughout, the side walls were a dark shade of blue, effectively setting off the beige paper of the drawings.

Preparatory drawings and those comprising the second cycle demonstrated that Janmot was a skilled draftsman—he grasps a sharp pencil in the Autoportrait (Self-Portrait) of 1832. Although the centrality of drawing to the artist’s creative process could only have been reinforced in the Ingres studio, Janmot’s graphic style became progressively more distant from that of his teacher. Subtle chiaroscuro softens the graphite pencil and stump drawings contemporaneous with the painted cycle (e.g., fig. 4). This gentle variant of the maestro’s manner gave way to vigorously expressive mark making as the artist worked in charcoal on the second cycle (e.g., fig. 5).

The exhibition included five subsidiary “cabinets” respectively titled “Pictorial and Illustrated Epics,” “The Soul and the Guardian Angel,” “The Ideal,” “Nightmare, the Dangers of the Unconscious,” and “Landscape and Reality.” Alongside works by Janmot, these galleries featured art produced by a heterogeneous cohort of visionaries, idealists, and dreamers. Some (e.g., Salvador Dalí, 1904–89) postdate Janmot’s death or were likely unknown to him (e.g., William Blake, 1757–1827). Others were acquaintances, such as Odilon Redon (1840–1916) who, along with Janmot, frequented the Parisian literary, musical, and artistic salon of the latter’s student Berthe de Rayssac (1846–92) in the 1870s. If the cost of these transhistorical panoplies was diminution of historical specificity, the benefit was an enhanced sense of Janmot’s singularity within these areas of common endeavor.

Janmot’s strange imagery—variously beautiful and disturbing—is admirably illuminated in a richly-illustrated catalogue by the exhibition’s organizers, Stéphane Paccoud, chief curator of nineteenth-century painting and sculpture at the Lyon Musée des Beaux-Arts, and Servane Dargnies-de Vitry, curator of painting at the Musée d’Orsay, each of whom provided a lucid introductory essay and insightful commentary on one of the cycles. Paccoud articulates the artist’s concerns and sets forth his career’s principal turning points. Investigating the relationship between word and image in Le Poème de l’âme, Dargnies-de Vitry makes a convincing case that Janmot took seriously both of his twin pursuits as poet and painter—that the verbal and visual imagery are effectively interwoven, and that the verse is integral to the ensemble, rather than adjunct to it.[6] Visitors could audibly experience the verbal dimension of the ensemble by listening, in a pair of niches, to recordings of the Lyonnais polymath (writer, director, actor, humorist, musician, and composer) Alexandre Astier (b. 1974) reading selections of the verse.

Essays by three scholars complement the curators’ contributions. Addressing two legacies that nurtured Le Poème de l’âme—Lyon’s fervent Catholicism and its tradition of arcane mysticism—Isabelle Saint-Martin characterizes the artist as an eclectic whose sources can only be traced through inference and sleuthing. That these include eighteenth-century editions of seventeenth-century religious emblem books squares with the insularity of Janmot’s work vis-à-vis contemporaneous Parisian art. Of the artist’s piety, there can be no doubt. As a student at the Collège Royal de Lyon (1826–31), he became close friends with Frédéric Ozanam (1813–53), a founder of the Société de Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, devoted to charity and spiritual vigilance of the poor. Ozanam was a mentee of the Abbé Joseph-Mathias Noirot (1793–1880), a professor of philosophy who would open class on his knees, invoking the Holy Spirit. A member of the Société and attendee at Noirot’s lectures, the artist admired and portrayed in 1846 Henri Lacordaire (1802–61), the militant ultramontane and charismatic sermonizer who reestablished the Dominican Order in France.

Saint-Martin’s essay touches on an aspect of Lyonnais culture that lay outside of Church dogma. In the 1770s and 80s, the author’s namesake Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin (1743–1803) sojourned in Lyon. Adopting as alias “The Unknown Philosopher,” the visitor was an apostle of illuminism—a nebulous movement seeking knowledge of the divine mysteries to which mankind was blinded by the Fall.[7] Janmot had contact with descendants of Saint-Martin’s host in Lyon and kindred spirit, Jean-Baptiste Willermoz (1730–1824). And he knew—from the Paris salon of a Lyonnaise, Juliette Récamier (1777–1849)—a Catholic monarchist from Lyon influenced by illuminism, Pierre-Simon Ballanche (1776–1847). Like Janmot, Ballanche aspired to create a vast, totalizing masterwork. His vision of mankind’s past, present, and future was to be embodied in a multi-part, epic text conceived in 1827 as Palingénésie sociale (Social Regeneration)—an undertaking realized, like Le Poème de l’âme, only in part. These counter-enlightenment currents align with Janmot’s contempt for the carnal, pagan aspect of the Italian Renaissance and his admiration of Girolamo Savonarola (1452–98) as a heroic martyr. Nor did Lyon’s grim fate during the French Revolution (abhorred by Janmot) encourage respect for humanism or reason. Having resisted the Convention, the city was subjected to siege and bombardment. During the five months following Lyon’s fall on October 9, 1793, there were almost 1,900 executions.

Given the artist’s preoccupation with spirituality and ideal beauty, Elena Marchetti’s essay regarding Janmot’s representation of landscape in Le Poème de l’âme is a revelation. Acutely observed renderings of trees, foliage, and meadows attest to habitual work en plein air amid the woods, marshes, and verdant plateau northeast of Lyon in the Bugey region, birthplace of the artist’s maternal line. Starting in the late 1830s, Janmot was a regular summer guest of the Lyonnais landscape painter Florentin Servan (1811–79) in the village of Lacoux in Bugey. There, together with another friend and landscapist from Lyon, Paul Flandrin (1811–1902), Servan and Janmot would pursue open-air study. Nor would one suspect that a painter ill at ease in his own time would be interested in photographic reproduction. In the final essay, Clément Paradis recounts the artist’s collaboration with Félix Thiollier (1842–1914) —a Saint-Étienne art collector and amateur photographer and archaeologist who made (and modified by hand) the carbon prints published concurrently with the Théolier edition of the complete verse.

The catalogue is a major contribution to Janmot studies, which commenced in earnest in 1969 with a four-volume doctoral dissertation by Élisabeth Hardouin-Fugier at the Université de Lyon, followed by her series of monographs.[8] Challenging the hegemony of secular subject matter in the Paris-centered literature on nineteenth-century French art, Louis Janmot: Le Poème de l’âme was a welcome sequel to an exhibition by Marchetti and Paccoud devoted to Ingres’s pious, Lyonnais pupil Hippolyte Flandrin (1809–64), the century’s preeminent French practitioner of religious art (apart from the non-believer Delacroix), and his artist brothers—also students of Ingres—Auguste (1804–42) and Paul.[9]

Both cycles of Le Poème de l’âme are discussed and comprehensively reproduced in the catalogue. This review can only sample an ensemble unfamiliar even to specialists in nineteenth-century European art. The painted cycle opens with the soul’s celestial birth. Incorporating the then popular motif of the guardian angel, the second painting Le Passage des âmes (The Passage of Souls; fig. 6) represents infant souls borne to earth by angels. In most of the remaining paintings, the soul takes the form of a male youth dressed in various tones of red, accompanied by a female soulmate of the same age clothed in white, both barefoot. One of the loveliest paintings, Le Printemps (Spring; fig. 7) shows the pair as young children in an Edenic meadow. Thanks to Marchetti’s essay, we can view the dewy freshness of the setting as the fruit of sustained outdoor study.

Blending politically-charged symbolism with bourgeois domesticity, the sixth painting, Le Toit paternel (The Paternal Roof; fig. 8) is no less surprising than the reasonable, if opinionated, discourse of Janmot’s sixty-seven-page review of the Salon of 1874 and his 555-page Opinion d’un artiste sur l’art (1887).[10] The Paternal Roof represents a family sheltered from a storm emblematic of the Revolution of 1848, initially supported by Janmot. At a window, the soul seems entranced by lightning; his white-clad companion shows concern. In reassuring contrast to the threat outside, the artist’s wife sews at a table beside a companion as an elder reads a psalm. Seated apart is Janmot. His uneasy attitude (echoed by an alert dog at his feet) registers alarm at the threat to the family posed by republican divorce legislation.

Like many in Lyon, Janmot was hostile to state-sponsored, secular education. He gave this pedagogy and its consequence sinister forms in two episodes that depart from the serenity of the other paintings, Le Mauvais Sentier (The Evil Path; fig. 9) and Cauchemar (Nightmare; fig. 10), numbers seven and eight, respectively. These date from a time of passionate debate regarding the place of religion in French education. In 1850, the Loi Falloux—named after the bill’s devout, monarchist sponsor, Count Alfred de Falloux (1811–86)—controversially permitted the establishment of Catholic primary and secondary schools alongside secular counterparts concurrently run by the government. In The Evil Path, the soul and soulmate fearfully ascend a vertiginous stairway lined with forbidding, gowned figures set in rectangular niches and bearing lit tapers. These are secular professors offering the baleful alternative to Catholic instruction, their perversion of wisdom signaled by an owl nesting in the gnarled branches of a dead tree.[11] Watching the youths from a doorway adorned with skeletons, a darkly clad, elderly woman represents false knowledge toxic to faith (fig. 11). In Nightmare, the vulnerable youths have entered her lair, prey to the despair that comes from believing solely in reason. Bearing away the soul’s unconscious companion, the predator chases the protagonist to the brink of an abyss before gnome-like witnesses. Primal fear is enhanced by the swift recession of an inclined corridor that suctions us toward a drop into the clouded sky. It is hardly surprising that The Evil Path and Nightmare impressed Baudelaire, translator of Edgar Allan Poe (1809–49).[12]

Some of the cycle’s most captivating paintings follow these dark imaginings. In number twelve, L’Échelle d’or (The Golden Ladder; fig. 12), Janmot drew on the biblical motif of Jacob’s dream, blending the sacred and profane in a nocturnal setting. The soul and his companion slumber as angels descend from, and ascend to, God—identified in the verse with ideal beauty. That Painting, Music, Architecture, Astronomy, Science, Theology, Philosophy, and Holiness are led by Poetry, buttresses Servan-de Vitry’s claim that the verse is integral to Le Poème de l’âme. In Poetry’s melancholy voice, Janmot reveals the motivation behind his tireless life work in pursuit of the Ideal and God: “It’s the ideal, it’s God that, dreamy and troubled, / I seek without rest, ever since that distant day, / In which beautiful and happy, but since then a sad exile, / The human soul fell from his divine hand.”[13]

Despite Janmot’s hatred of the Renaissance, there is a reminiscence of Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510) in number thirteen, Rayons de soleil (Sun Beams; fig. 13), which features a circle dance at the close of an autumnal day. Turning away from the tempting allure of a dancer in multi-colored dress and floral crown, the soul faces his white-clad soulmate. Chaste attraction is again represented in the stunning fourteenth canvas, Sur la montagne (On the Mountain: fig. 14). Here the couple’s spiritual ascent takes the form of a climb up a hill, their gendered innocence mirrored in flowering plants, one upright (before the soul) and one bending (behind his companion). The soul’s androgynous features temper the note of desire struck by his rapt gaze.

The soul’s longing is again represented in the seventeenth painting, L’Idéal (The Ideal; fig. 15), in which the pair soars above cloud-piercing, forbidding crags. Here the soul’s beloved prepares to depart, exhorting him to seek the ideal: “Only it can finally provide white wings / that one day will / Carry your heart, delayed by mortal loves / Toward immortal love.”[14] In the eighteenth and final canvas, Réalité (Reality; fig. 16) the bereft soul presses a funerary cross into the grave of his departed doppelgänger at a specific site in Bugey.

Fascinated by Janmot’s 1854 Paris exhibition, Gautier was astonished that a painter would try to visualize such immaterial subjects: “M. Janmot has found for these scenes of the other world deathly pallors, tones of wax and the host, past grays and future blues unknown to human palettes. One would say the shadow of a dream caught by daguerreotype in those regions of the infinite beyond the light of stars.”[15] Delacroix—later praised by Janmot—was ambivalent. Having suffered public incomprehension, he empathized with Janmot’s outsider status in a Journal entry written a month after the opening of the Exposition Universelle: “This naïve artist will never be accorded a particle of the justice to which he is due.” In Janmot’s paintings, Delacroix discerned “a remarkable Dantesque fragrance. . . . He brings to mind those angels from the purgatory of the famous Florentine; I love those dresses, green as the meadow grass in the month of May, those inspired or dreamt heads that are like reminiscences of another world.” Delacroix was dismayed, however, by what he considered poor technique and inaccessible imagery, observing that Janmot “speaks a language which no one else ever will speak; it is not even a language; but one perceives his ideas through the confusion and the naïve barbarism of his means of rendering them.” Delacroix predicted that Janmot would never develop beyond the ability with which he was born, likening him to a bird dragging its shell. Despite these reservations, Delacroix was impressed by an originality impervious to the homogenizing instruction that Ingres imparted to his other students: “This is an entirely singular talent in our place and time.”[16]

Delacroix’s admirer Baudelaire was more critical. Conceding that “there was in the composition of these scenes [by Janmot], and even in the bitter color in which they were arrayed, an immense charm that is difficult to describe, something of the sweet savor of solitude, of the sacristy, of the church, and of the cloister, an unconscious and childish mysticism,” Baudelaire considered Le Poème de l’âme “trouble et confuse” (“murky and vague”); he was unsure whether it represented a male and female soul or twin counterparts of one soul.[17] And he bristled at Janmot’s Lyonnais background: “This is a religious and elegiac spirit, he must have been marked from youth by Lyonnais bigotry.”[18] In Lyon, he complained, “ideas are managed. . . with difficulty. All that comes from Lyon is meticulous, slowly elaborated, and timid. . . . You could say that brains there are stuffed up like a nose.”[19] Baudelaire wrote from experience, having attended as a youngster the Collège Royal de Lyon—Janmot’s alma mater.

Whereas the opinions of Delacroix and Baudelaire remained private during their lifetimes, the paintings were publicly attacked in the Catholic paper L’Univers. Having “unfortunately strayed into the nebulous and abstract conceptions of Idealism,” the artist was taken to task for not considering original sin, baptism, or life’s temptations and trials.[20] This critique must have deeply wounded Janmot, for it came from a close friend, a Lyonnais disciple of Lacordaire and fellow Ingres student, Claudius Lavergne (1815–87). In their youth, the artists had traveled together to Rome; when Lavergne fell ill, Janmot cut short his stay to see his companion home. That Lavergne broke with Janmot reflects the radically wayward character of Le Poème de l’âme. In regard to the unorthodoxy of the paintings, it is telling that Delacroix, Gautier, and Baudelaire appreciated them for reasons distinct from their intended didactic purpose.

The second cycle was apparently unknown to Delacroix, Gautier, Baudelaire, and Calonne. Janmot’s abandonment of paint and canvas in favor of large-scale charcoal drawings may have been prompted by viewing the work of another artist from Lyon at the 1855 Exposition Universelle. These were studies for Paul Chenavard’s (1807–95) staggeringly outsized program of at least sixty-three murals setting forth humanity’s universal history. Intended for the interior of the Panthéon, the project had been thwarted by clerical opposition.[21] Bridging ideological difference, Janmot and Chenavard became friends.

Bathed in crepuscular light, the second cycle’s charcoal drawings are mostly lugubrious in content, reflecting political bile and personal loss. Some of the images are bluntly reactionary and freighted with the former liberal’s hatred of the Third Republic. The death of Janmot’s mother in 1838 and the passing of Ozanam in 1853 had impacted the first cycle. Commencing in the wake of the debacle at the 1855 Exposition Universelle, work on the second cycle coincided with the death of the artist’s newborn son in 1865 and the wartime sack of his Bagneux home and studio in 1870, shortly after the death of Janmot’s wife, Léonie. In place of the lyrical mysticism of the painted cycle, the drawings demonstrate that temptation and torment are the cost of redemption for the soul, now grown to mustachioed adulthood.

In contrast to chaste pursuit of the ideal in the first cycle, the unattached soul abandons himself to sensual pleasure in L’Orgie (The Orgy; fig. 17). This drawing (number eight) differs in tenor from its antecedent, Les Romains de la décadence (Romans of the Decadence, 1847) by Thomas Couture (1815–79). In Couture’s painting, stern antique statues seem disgusted by the revelers. In contrast, Janmot’s inclusion of sculptures of Venus and Bacchus (i.e., lust and gluttony) indicts pagan antiquity. In the ninth drawing, Sans Dieu (Without God; fig. 18), the faithless soul is at the brink of disaster. Seated on a sawn, dead tree at the edge of a precipice, he is depicted as an anti-Evangelist, spurning the Gospels with his foot while pointing to a cloaked figure. This is the Phantom, who subsequently subjects the soul to torture and precipitates his fall.

That catastrophe is represented in drawing eleven, Chute fatale (Fatal Fall; fig. 19). Tumbling downward, the soul reaches in vain toward the Phantom, whose true name (“Fatality”) is inscribed along with “Revolt” and “Materiality” in the book he holds. Seated beneath the serpent-bearing Tree of Knowledge (i.e., under the aegis of original sin), veiled Fatality is flanked by two bare-breasted women. At left, Revolt brandishes torch and dagger; the conflagration behind her refers ominously to the recent Commune. At right, seductive Materiality holds a goblet filled by a winged genius. To the rear, a classical temple speaks of the artist’s hostility toward pagan antiquity.

Following this dismal, turgid allegory, there are scenes of torment. Then, the cycle takes an optimistic turn. The title of the final drawing (number sixteen), Sursum corda! (Let Us Lift up Our Hearts!; fig. 20), is borrowed from the Mass liturgy. Here, the punished soul is redeemed by his beloved soulmate, personified as Dante’s Beatrice, in the presence of theological and cardinal virtues, most of whom bear the features of the artist’s five daughters. In a heavenly zone, Christ (as the Good Shepherd) is worshiped by a blessed host, which includes the artist’s deceased wife (in the guise of Mary Magdalene), Lacordaire, and the Lyonnais cult healer Jean Vianney (1786–1859), popularly known as the Curé d’Ars. In the verse, Beatrice dampens this cheer by exhorting the soul to remain vigilant as he faces further trials—perhaps planned for the two unexecuted cycles.

Notwithstanding this pious conclusion, Janmot’s decades of labor hardly produced an effective guide to Christian devotion. This, despite Ozanam’s assertion that Le Poème de l’âme would be offered “à la bénédiction de Dieu et à l'instruction des hommes” (“to the benediction of God and the instruction of mankind”).[22] Though appreciative of the paintings, the critic Calonne wondered who would buy them and where they could be hung.[23] Like other spiritual and artistic radicals—William Blake and Philipp Otto Runge (1777–1810) spring to mind—Janmot sacrificed public comprehension and Christian orthodoxy to the dictates of private vision.

Viewing the exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay in proximity to paintings by the impressionists and their contemporaries, whether vanguard or academic, brought home the distance of Le Poème de l’âme from the nineteenth-century Parisian art world. The disparity is all the more striking given that, in 1861—hoping to gain commissions and disappointed by his failure to be named director of the Lyon École des Beaux-Arts—Janmot moved to Paris. Before the financially insecure artist relocated to Toulon in 1879, he exhibited examples of his work in the Salon (1861, 1865, 1868), in the Exposition Universelle of 1867, and in an exhibition (1867) organized by the Société de Saint-Vincent-de-Paul.

Such was the embittered artist’s longevity that he could have witnessed French culture undergoing a sea change prophesied by Le Poème de l’âme. In the nineteenth century’s twilight, contemporaneity and secular realism were challenged by symbolism, Catholic revival, and a vogue for the occult. Like Janmot, the Sâr Mérodack Joséphin Péladan (1858–1918), Lyonnais founder of the Salons de la Rose + Croix, was steeped in their city’s legacy of Catholic mysticism. His idealism and hatred of realism are conveyed by Carlos Schwabe’s (1866–1926) poster for the first exhibition of the Salon de la Rose + Croix, held in the year of Janmot’s death (fig. 21). Schwabe shows two women ascending a stairway into the realm of the ideal. They contrast with a woman mired in materiality below. The similarity to The Golden Ladder (see fig. 12) speaks of Janmot’s enduring legacy. In a recent book, I doubted that Janmot would ever be the subject of a world-class exhibition comparable to those dedicated to Delacroix.[24] I am delighted to confess that the outstanding exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay proved I was mistaken.

Notes

[1] I am grateful to Stéphane Paccoud, Conservateur en chef, chargé des peintures et des sculptures du XIXe siècle, Musée de Beaux-Arts, Lyon for providing information and for inviting me to present a paper, “Janmot and Delacroix: Perpendicular Lives,” at the “Journée d’études: À la croisée des pratiques artistiques. Louis Janmot et les arts au XIXe siècle,” Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon, November 17, 2023. I also wish to thank Henrique Simoes, Chargé du service images, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon, for providing digital images and granting permission for their publication. This review incorporates material from Jonathan P. Ribner, Loss in French Romantic Art, Literature, and Politics (New York and London: Routledge, 2022), 75–88, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/.

[2] Louis Janmot, L’Âme, Poème. Trente-quatre tableaux et texte explicative (Saint-Étienne: Théolier, 1881), viii. All translations are the author’s.

[3] Charles Baudelaire, Critique d’art, suivi de Critique musicale, Claude Pichois, ed., Claire Brunet, int. (Paris: Gallimard, 1992), 264. Quotations from Baudelaire herein are from the notes (dating largely from 1858–60), for an unpublished article published posthumously as “L’Art philosophique,” reprinted in Baudelaire, Critique d’art, 258–65. The project is referred to under various titles in the author’s correspondence. See the editor’s note, 606–07.

[4] Prior to exhibiting the paintings in 1854, Janmot had the eighteen poems corresponding to the painted cycle published by the Lyon press of Aimé Vingtrinier.

[5] See Sylvie Ramond and Pierre Vaisse, eds., Le Temps de la peinture, Lyon 1800–1914, exh. cat. (Lyon: Musée des Beaux-Arts, in association with Paris: Éditions Fage, 2007).

[6] For analysis of the verse, see also Frank Paul Bowman, “Le texte du ‘Poème de l’âme’,” in Wolfgang Drost, Élisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, and Birgit Gottschalk, eds., Louis Janmot, Précurseur du symbolism, Avec le texte intégral du “Poème de l’âme” (1881) (Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter, 1994), 185–95. For the complete verse, see Louis Janmot, Le Poème de l’âme: Trente-quatre tableaux et texte explicative, Patrice Béghain, ed. (Paris: Éditions Fage, 2023); and Louis Janmot, Le Poème de l’âme/The Poem of the Soul, bilingual edition, Dominique Brachlianoff, ed., Brian Holmes, trans. (Lyon: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon and Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1995).

[7] For Saint-Martin and illuminism, see Frank Paul Bowman, Le Christ des barricades (1789–1848) (Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 1987), 45–8; see also the entries “Illuminism” and “Saint-Martin,” in The New Oxford Companion to Literature in French, Peter France, ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), 399, 734; and Paul Bénichou, Le Sacre de l’écrivain, 1750–1830: Essai sur l’avènement d’un pouvoir spirituel laïque dans la France moderne. 2d ed. (Paris: Librairie José Corti, 1985), chap. 3.

[8] See Élisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, “Louis Janmot” (PhD diss., Université Lyon 2, 1969); Élisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, “Le Poème de l’âme” par Louis Janmot (1814–1892) (Châtillon-sur-Chalaronne: Éditions La Taillanderie, 2007); Élisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, Louis Janmot 1814–1892 (Lyon: Presses Universitaires de Lyon, 1981); Élisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, “Le Poème de l’âme” par Janmot: Étude iconologique (Lyon: Presses Universitaires de Lyon, 1977); and Élisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, and Bernard Berthod, Louis Janmot, peintre de l’âme (Châteauneuf-sur-Charente: Frémur, 2020). Janmot’s art is also discussed in Bruno Foucart, Le Renouveau de la peinture religieuse en France (1800–1860) (Paris: Arthéna, 1987), 268–71.

[9] Elena Marchetti and Stéphane Paccoud, Hippolyte, Paul, Auguste: Les Flandrin, artistes et frères, exh. cat. (Lyon: Musée des Beaux Arts, 2021).

[10] See Louis Janmot, Salon de 1874, quelques considérations générales (Paris: Jules Le Clère, 1874); and Louis Janmot, Opinion d’un artiste sur l’art (Lyon: Vitte & Perrussel and Paris: Victor Lecoffre, 1887).

[11] For a discussion of The Evil Path in the context of hostility toward secular education, see Michael Paul Driskel, Representing Belief: Religion, Art and Society in Nineteenth-Century France (University Park: Penn State University Press, 1992), 41.

[12] See Baudelaire, “L’Art philosophique,” in Baudelaire, Critique d’art, 264.

[13] “C’est l’idéal, c’est Dieu que, rêveuse et troublée, / Je cherche sans repos, depuis ce jour lointain / Où belle, heureuse alors, depuis triste exilée, / L’âme humaine tomba de sa divine main.” Janmot, Le Poème de l’âme, Béghain, ed., 56, lines 816–20.

[14] “Lui seul qui peut enfin donner les blanches ailes / Qui porteront un jour / Votre coeur attardé par des amours mortelles / Vers l’immortel amour.” Janmot, Le Poème de l’âme, Béghain, ed., 77, lines 1234–37.

[15] “M. Janmot a trouvé pour ces scenes de l’autre monde des pâleurs mortes, des tons de cire et d’hostie, des gris passés et des bleus futurs inconnus sur les palettes humaines. On dirait l’ombre d’un rêve prise au daguerréotype dans ces régions de l’infini où la lumière des astres n’arrive pas.” Théophile Gautier, “L’Âme, par M. Louis Janmot,” Le Moniteur universel, May 26–27, 1854, reprinted in Drost et al., eds, Louis Janmot, 140–44.

[16] “Il y a chez Janmot un parfum dantesque remarquable. Je pense en le voyant à ces anges du purgatoire du fameux Florentin; j’aime ces robes vertes comme l’herbe des prés au mois de mai, ces têtes inspirées ou rêvées qui sont comme des réminiscences d’un autre monde. On ne rendra pas à ce naïf artiste une parcelle de la justice à laquelle il a droit. . . . [I]l parle une langue qui ne peut devenir celle de personne; ce n’est pas même une langue; mais on voit ses idées à travers la confusion et la naïve barbarie de ses moyens de les rendre. C’est un talent tout singulier chez nous et dans notre temps; l’exemple de son maître Ingres, si propre à féconder, par l’imitation pure et simple de ses procédés, cette foule de suivants dépourvus d’idées propres, aura été impuissant à donner une exécution à ce talent naturel, qui pourtant ne sait pas sortir des langes, qui sera toute sa vie semblable à l’oiseau qui traîne encore la coquille natale et qui se traîne encore tout barbouillé des mucus au milieu desquels il s’est formé.” Eugène Delacroix, Journal, Michele Hannoosh, ed., vol. 1, 1822–1857 (Paris: José Corti, 2009), 912–13 (Champrosay, June 17, 1855).

[17] “[I]l faut reconnaître qu’au point de vue de l’art pur il y avait dans la composition de ces scènes, et même dans la couleur amère dont elles étaient revêtues, un charme infini et difficile à décrire, quelque chose des douceurs de la solitude, de la sacristie, de l’église et du cloître; une mysticité inconsciente et enfantine.” Baudelaire, “L’Art philosophique,” in Baudelaire, Critique d’art, 263-64.

[18] “C’est un esprit religieux et élégiaque, il a dû être marqué jeune par la bigoterie lyonnaise.” Baudelaire, “L’Art philosophique,” in Baudelaire, Critique d’art, 263.

[19] “Ville singulière, bigote et marchande, catholique et protestante, pleine de brumes et de charbons, les idées s’y débrouillent difficilement. Tout ce qui vient de Lyon est minutieux, lentement élaboré et craintif. . . . On dirait que les cerveaux y sont enchifrenés.” Baudelaire, Critique d’art, 261.

[20] “[I]l s’est malheureusement égaré dans les conceptions nébuleuses et abstraites de l’Idéalisme.” Claudius Lavergne, “L’Exposition universelle de 1855: Beaux-arts,” L’Univers (1855), 99–101, quoted in Drost et al., eds., Louis Janmot, 150.

[21] For Chenavard’s project, see Daniel R. Guernsey, The Artist and the State, 1777–1855: The Politics of Universal History in British and French Painting (Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate, 2007), chap. 3.

[22] Quoted from Ozanam’s correspondence (October 14, 1849), in Hardouin-Fugier, “Le Poème de l’âme” par Janmot: Étude iconologique, 110.

[23] Alphonse de Calonne, “Le Poème de l’âme en peinture et en vers, par M. Louis Janmot,” Revue contemporaine 14 (June–July 1854): 136–47, reprinted in Drost et al., eds, 147.

[24] See Ribner, Loss, 87.