Artful Subversion: Empress Dowager Cixi’s Image Making by Ying-chen Peng

Reviewed by Michael J. HatchMichael J. Hatch

Associate Professor of Fine Arts

Trinity College

Email the author: michael.hatch[at]trincoll.edu

Citation: Michael J. Hatch, book review of Artful Subversion: Empress Dowager Cixi’s Image Making by Ying-chen Peng, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.1.9.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Ying-chen Peng,

Artful Subversion: Empress Dowager Cixi’s Image Making.

New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023.

208 pp.; 82 color and 19 b&w illus.; selected names and terms; notes; selected bibliography; index.

$50 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978–0–300–26343–5

In Artful Subversion: Empress Dowager Cixi’s Image Making, Ying-chen Peng recuperates the voice of Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908), one of late imperial China’s most important and controversial leaders, through an accounting of the visual and material culture she commissioned for the late Qing dynasty court. Each chapter explores Cixi’s efforts in a particular medium, including her portraits in painting and photography; her designs for palace renovations and new construction; sets of porcelain she commissioned for her private palaces; the calligraphy and paintings she made as imperial gifts; and, as an epilogue, her mausoleum. Throughout these chapters, Peng shows how Cixi shaped physical spaces and visual experiences at court in order to redefine gender boundaries that otherwise constricted her involvement in political decision-making. This “artful subversion”—Cixi’s strategic use of the arts to gain greater agency in a patriarchal system—gives the book its title.

Confucian expectations for proper behavior by women at court create the central tension in Peng’s narrative. These dictated everything from where women were seen, and by whom, to what colors and motifs they could wear. We learn that as Cixi matured she put increasing pressure on the spaces and symbols allowed to her by gender conventions. The target of these artistic subversions was not just constraints on her personal expression. This was not art for art’s sake. By making her presence at court multi-faceted, multi-sensory, and undeniable, Cixi was able to undermine patriarchal Confucian prohibitions against her participation in court politics.

Peng spends little time describing how Cixi shaped policy and guided China with the political agency she gained from these artistic commissions. Rather than focusing on economic and cultural events in greater China that were impacted by court politics, Peng keeps her narrative honed on the insular world of the court. At times, this seems entirely appropriate to the subject of the book, an artistic biography of Cixi, whose own circulation was largely limited to imperial palaces and gardens. The clear presence of Cixi’s hand in political events of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and the efforts of many previous authors to describe it allows Peng to leave these implications unarticulated to some degree. However, sometimes the reader begins to want for a greater understanding of how Cixi’s artful subversions at court mattered for the rest of the country.

A brief orientation to the major events and politics of Cixi’s life come in the introduction, along with other foundational knowledge such as the nature of Confucian thinking toward women at court, existing scholarship on powerful empresses and empress dowagers who preceded Cixi as politically-motivated patronesses of the arts, and a discussion of the central conundrum facing any biographer of a woman at court—a lack of primary documentation written by her. Cixi’s career as empress dowager at the Qing dynasty court in Beijing was remarkably long. After becoming a consort to the Xianfeng emperor (r. 1850–61) in 1852, Cixi went on to preside over three consecutive regencies for a period that lasted more than four decades. She first guided her son, the Tongzhi emperor (r. 1861–75), who inherited the throne at age five. Tongzhi died of smallpox only a few years after coming into the full power of the throne, leading to Cixi’s second stewardship of the court during the reign of her nephew, the Guangxu emperor (r. 1875–1908), who inherited at age four. To become heir, Guangxu first had to be adopted as the son of an emperor. Cixi revealed her ambitions at this point. Tradition should have dictated Guangxu become the adopted son of his recently deceased cousin, Tongzhi. This would have made Guangxu’s birthmother the new empress dowager and regent. Instead, Cixi and her allies pushed to have the boy named as a son of the previous emperor, Xianfeng, which made him Cixi’s adopted son and allowed her to maintain her position as regent. Once the Guangxu emperor came into the full power of the throne, he attempted to reform the Qing government in 1898, in what was later called the Hundred Days Reform. Cixi quashed these ambitions and placed the emperor under house arrest for the remainder of his life, leading to her third regency.

In all three of these periods, Cixi made decisions for the empire beneath the name of a boy emperor, first as part of a triumvirate of regents including the Xianfeng emperor’s first wife, Ci’an (1837–81), and Prince Gong (1833–98), and from 1884 on as the sole regent. Each transition gave her an increasing amount of say over politics at court, culminating in her most impressive political feat—the outmaneuvering of the reforms put forward by the Guangxu emperor and his allies. Peng’s book aims to help answer the question of how Cixi accumulated this influence despite the existing Confucian prohibitions designed to prevent the rise of a dowager empress as de facto ruler. Each chapter contributes to Peng’s convincing overall argument that as Cixi bent the court’s gendered rules around artistic authorship and symbolism, her greater aim was to gradually reposition the boundaries of her political possibilities.

Chapter 1, titled “Fashioned Exposure,” analyzes portraits of the Empress Dowager in various media, including Chinese paintings, oil paintings by Western portraitists, and photography. Peng accounts for a total of eight Chinese paintings, thirty-one sets of photographs, and four oil portraits, describing Cixi as “the most illustrated imperial woman in China” (19). As formally posed images of her person, these are the most direct forms of representation Cixi worked to create. The chapter begins with two public-facing portraits in oil on canvas by Hubert Vos (1855–1935), one made in 1905 for the throne and another unauthorized version that he exhibited in the 1906 Paris Salon (fig. 1). We then jump back in time to Cixi’s earliest court-facing portraits in ink and pigment on paper from 1865, from which we proceed through images made between these two dates, ending with a lavish portrait by Katherine Carl (1865–1938) displayed at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Peng divides these portraits into three periods: the early regency; a middle period in which Cixi often took on the persona of the Buddhist deity Guanyin; and a later period following the Hundred Days Reform and the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, when a concern for international relations encouraged her to direct her portraits toward audiences outside of the court.

Several of these images have been the focus of previous scholarship. By bringing them together in relation to the chapters that follow, Peng encourages us to consider Cixi’s many forms of self-representation in a more holistic sense. She describes this first chapter as the keystone for the whole book, and it does feel the fullest because it spans all three regencies while also introducing the analytical method that Peng uses through the rest of her chapters: iconographic interpretations as seen through the lens of Confucian gender norms. As an example, the inclusion of male-coded objects such as a snuff powder dish or a book in an 1865 portrait (fig. 2) breaks portrait precedent for women because these are male-coded objects. By including these in a painting made during her first regency, Cixi presents herself as having the “capacity to rule like a man” (20). Likewise, in another painting for court, an orchid branch pinched between Cixi’s fingers foregrounds the feminine root of her power at court while alluding to her first court title, “Worthy Lady Orchid,” as well as her “self-possession” (24). Peng spends time analyzing the colors and motifs of the matriarch’s robes in these images as well, introducing the fact that Cixi created her own personal textile manufactory in 1890, a sign of her direct agency over an increasing number of visual and material cultures at court during this later period of her rule.

Peng argues that Cixi’s non-normative assertions of a self that existed somewhere between genders become more explicit in later portraits, beginning with images of her as the bodhisattva Guanyin. These allowed the aging Cixi to co-opt an existing model of fecundity that was independent of her sexuality. After the diplomatic blunder of her support for the anti-Western Boxer Rebellion of 1900, she increasingly directed her images toward international communities in order to reform her degraded public image. Cixi began a public relations campaign in photographs and oil portraits, including a three-foot square photographic print sent to President Roosevelt in 1905 and the Carl portrait for the St. Louis World’s Fair. The latter was the only instance in which a Chinese monarch provided their image for public viewing. On top of that notable point, this image also bypassed general Confucian restrictions on the presentation of women beyond the domestic sphere.

Peng’s reading of the Carl portrait as a performance of gender reveals the blunt ways in which the empress dowager put classical motifs to use (fig. 3). A preponderance of phoenixes and peacocks serve as a feminine backdrop to the image, but the exotic hardwood frame around the painting, carved with numerous dragons, evokes male symbols of imperial power. Peng calls the “overwhelming” frame “masculine in its own right” (59). In this world, it seems a motif or a space is rigidly defined as either masculine or feminine, and Cixi transgressed the limits of Confucian propriety by using both at will. This same fundamental approach to interpretation grounds most of the visual analysis in the following chapters. References to gender in the Qing court may have been as direct as this. However, in an era of scholarship where gender theory can be a subtle scalpel for dismantling normative modes of interpretation, these images often seem to ask for more nuanced analysis.

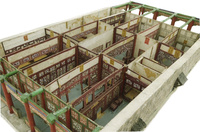

Chapters 2 and 4, “An Unfulfilled Dream” and “Reconfigured Patriarchal Space,” examine Cixi’s architectural ambitions, first with a set of 1873 plans for a residential palace building in the Garden of Perfect Brightness (Yuanming yuan) that was never completed, and second with her expansions within the Forbidden City and her 1884 design of the Garden of Nurtured Harmony (Yihe yuan). The garden sites were located in the northwestern area of Beijing that was looted and sacked by the Eight Allied Armies in 1860. The timing of these proposals also conveniently coincided with the end of Cixi’s regencies over Tongzhi and Guangxu, and both appear to be efforts by her young charges to assert their independence by distancing her from court. Yet, as Peng shows, Cixi took unprecedented control over these projects, shaping them to a presentation of self that far exceeded her predecessors in terms of scale and decoration. Two models for the 1873 plans still remain and are among the more fascinating objects revealed by Peng’s research (fig. 4).

Peng measures Cixi’s architectural transgressions by noting the greater scale of her quarters compared to those of the senior dowager empress, Ci’an, and even to those of the emperor himself. She also labels the inner quarters of the Forbidden City as the emperor’s private domain, noting that because no imperial censors or male members of the imperial family objected when Cixi took control of their partial redesign, the court was now under matriarchal management rather than patriarchal rule. Still, there were limits to Cixi’s control, such as where and how she could receive high officials or foreign dignitaries. The later set of residential palaces in the Garden of Nurtured Harmony became a transgressive site for such receptions, where Cixi flouted Confucian gender boundaries between the outer public court of the emperor and the inner domestic palaces to which the only males allowed were physicians, servants, or family members. By creating a space outside of the Forbidden City for such meetings, Cixi could avoid direct conflict with the norm.

Chapter 3, “Gendered Vessels,” considers the porcelain Cixi commissioned from the imperial kilns after their reopening in 1866. First came Tongzhi’s wedding service, and then, later in 1874, a set of brightly decorated wares known as the Studio of Utmost Grace (Daya zhai) porcelains, which were meant for Cixi’s first architectural project in the Garden of Perfect Brightness. The name Studio of Utmost Grace came from one of the Xianfeng emperor’s early names for the young Cixi, and her use of it twenty years later bolstered her relationship to the root of her power at a moment when her son, Tongzhi, was beginning to distance her from court. The gendered powerplay here, according to Peng, happens at the level of the commission itself, as imperial porcelain orders during the previous reigns of the Qing emperors were male-initiated. The name Fan Changlu may stand on the official command for production, but Fan was a servant in Cixi’s palaces, and the order came from the embroidery workshop within the palace, an institution long associated with imperial consorts.

The exquisite designs for these wares still exist and, as Peng points out, these images outstrip any proposals for prior court porcelain commissions (fig. 5). The subtle tones achieved with washes of water-based pigments on paper, called boneless technique for its lack of linear brushwork, were transferred to a new material, porcelain, through a difficult enameling technique. The demands of this process also offer us one of the few moments when we hear Cixi’s voice directly, in her corrections to the faulty enameling of the earlier wedding wares for her son. The rarity of hearing from Cixi in her own words reminds the reader of one of the book’s key methodological concerns—how do we reconstruct Cixi’s voice and agency from sources that tend to exclude direct record of it? Reading between the lines and interpreting Cixi’s decisions through the commands of officials loyal to her or in the edicts of her imperial charges leaves us open to accusations of overdetermination or selective interpretation. Throughout the chapters, Peng manages to tread this line carefully by focusing on visual and material culture rather than privileging primary documents written by the empress herself. In the last chapter, this issue of direct and indirect voice becomes central.

In chapter 5, “Elegant Gifts for Publicity,” Peng shows us how Cixi extended her influence through painting and calligraphy made both by her own hand and under her name by court painters. Peng rightly directs us away from previous scholarship that focused on whether Cixi was a skilled artist or if these artworks were authentic to her hand, approaches that force the artworks to make meaning under a male literati brushwork paradigm. Instead of using these artworks to demonstrate gentlemanly self-cultivation, Cixi extended her imperial presence through them, making them political gifts for both private and public audiences in domestic and international spheres. The volume of painting and calligraphy by Cixi (over seven hundred objects in the Beijing Palace Museum collection alone) attests to their usefulness to her in this regard and to the fact that the act of gift-giving was more important than the question of whether Cixi’s brush actually touched the artwork.

The defiance of gender expectations here builds upon the precedent of Peng’s earlier chapters. Previously, the brushwork of court women had largely been used to gain the eye of the emperor, and rarely circulated beyond the inner palaces. Male emperors traditionally performed public assertions of presence through the imperial brush. To tie her work to these precedents, Cixi explicitly emulated paintings made by earlier emperors, especially those of the first Qing emperor to rule over China, Shunzhi (r. 1644–61).

The book closes with an epilogue, “The Hinterland of Matriarchy,” that describes the motifs of Cixi’s mausoleum as the “final act of her artful subversion” (155). These buildings were begun in 1873, well before the death of the Tongzhi emperor and before Cixi’s influence had grown to its greatest reach. But in 1895, the mausoleum underwent repairs, and at this time Cixi’s control of court went largely unchallenged. Her additions at this point included the motif of the phoenix leading the dragon as well as stand-alone dragons, which would have violated Confucian gender decorum for an empress dowager. Though the Qing mausoleums were meant only for members of the imperial family, the display made a clear statement about Cixi’s influence on the imperial line. This natural ending point to a narrative about Cixi’s artistic commissions at court also leads to the enduring question of how we continue to remember her.

Only three years after Cixi’s death, internal rebellion brought Qing dynasty rule over China to an end, and many laid the blame for this at her feet. Whatever role Cixi’s decisions had in weakening the state, many explanations of the dynasty’s fall conveniently and unfairly focused on her gender and age. Her reputation as an overbearing and malignant matriarch—the likely root for the early twentieth-century stereotype of the “dragon lady”—was already being stoked abroad well before her death, especially during the debacle of the Boxer Rebellion, as seen in a poem on the cover of the July 14, 1900 edition of the French magazine Le Rire (fig. 6). The poem is purportedly translated from Chinese, though its racist overtones and male chauvinist descriptions of the empress dowager clearly indicate otherwise:[1]

I live in Peking, the sublime city where

I reign under the sweet name of Dowager.

I detest when you bore of me, and I abhor when you malign a

one [such as me] who only ever loved this country, so yellow, China!

Seeing my visage, such an unmaidenly face,

all fear China won’t be run by the Chinese race;

until God, reading the ancient canons

grows teeth in the mouths of old hens.

The poem casts Cixi as vain, attention-seeking, and thin-skinned in the face of foreign criticism of her support for the anti-Western Boxers. It also describes her as homely and aged, aspects the author directly connects with accusations of political impotency. Outside of China, Cixi has never entirely shed this agist, racist, and misogynist image. Several of these overtones are certainly present in what is perhaps the most famous foreign image of Empress Dowager Cixi, her short but captivating presence in The Last Emperor (dir. Bernardo Bertolucci, 1987), a film that dominated the 1988 Academy Awards and reignited Western fascination with China just a few months before events in Tiananmen Square would direct that global attention in an entirely different direction.

In her one scene in Bertollucci’s film, the aged Cixi is seen on her ornately carved and mobile deathbed, a throne in all but name, and one from which she is too weak to rise.[2] A large retinue of richly adorned ladies-in-waiting and eunuchs flank her, while the movie’s naive title character, two-year-old Aisin-Gioro Puyi (1906–67), is led to the throne by his father to bow in reverence to the de facto court in front of them. The empress dowager, whose age and caked make-up clearly confuse the boy, confers her power to the child who would be the Xuantong emperor (r. 1908–12) just before her final breath. As she does so, she looks up to the “black pearl,” a large, mirrored orb set into the ceiling, to contemplate her reflection one last time (fig. 7). Bertolucci’s dramatic license in this moment aptly highlights the importance Cixi placed on her own image. The various modes of self-representation that Cixi cultivated at the Qing court were the tools by which she also cultivated power in an otherwise male-dominated world. But until Peng’s book we have not appreciated the subversive nature of those images or the agency they offered.

In many ways, the powerful matriarch has always been a cypher for foreign understanding of China, though the international community’s general opinion of her has shifted very little since 1900. Despite many attempts to explain her exceptional place in history and in historical imagination, it is still common to see her from the outside and through lenses that threaten to strip her of her voice. As Pamela Crossley, the eminent historian of Qing-dynasty China, put it in her review of one of the recent trade biographies of Cixi, “Empress Dowager Cixi of the Qing dynasty is one of those historical figures who are renovated from time to time as the moment demands.”[3] Peng’s book offers us a new way to understand Cixi through the lens of material culture. While we still observe her from the outside in a way, through the various decorative skins and embellished surfaces with which she surrounded herself and projected her presence, we also finally see how she authored her own image. Through Peng’s analysis, we understand that Cixi’s shrewdness as a politician was directly tied to her cleverness as a designer.

The boons of Peng’s approach aside, there were a few missed opportunities as well as some areas where simple additions would have helped the argument, as is the case with any book. For an argument built around identity and gender, such ideas often go under-examined. Peng makes promising nods in this direction, such as, “Cixi simultaneously claimed personal authority and upheld the Qing imperial patrimony” (2), but in the end we are left wondering what it means to support patriarchy while also asserting female agency. Analysis tends toward more direct readings of images through conventional Confucian gender symbolism rather than leaning into the messy and potentially contradictory possibilities of gender theory. In the category of smaller gripes, an appendix of Cixi’s life events alongside major political events would have been welcome. Likewise, readers not already familiar with the various palace compounds of Beijing may struggle to visualize Peng’s arguments in chapters 2 and 4 by means of the maps and architectural plans offered.

Despite the inevitable wish list that any individual reader may bring to Peng’s book, it is a welcome contribution to the field. Chapter 1 may be especially useful for teaching upper-level undergraduate seminars on late Qing-dynasty portraiture and global interactions. Chapters 4 and 5 will be useful for teaching Chinese architectural history and later Chinese painting history. Peng’s focus on female agency through the arts in imperial China aligns her book with research over the past decade and a half by Hui-shu Lee, Dorothy Y. Ko, Yuhang Li, and the late N. Harry Rothschild.[4] This work also resonates with the recent reconsideration of the nineteenth century that has been percolating across the Chinese humanities, and especially in art history, as evidenced by the blockbuster British Museum exhibition, China’s Hidden Century, 1796–1912 (May 18–October 8, 2023).[5] When this first stand-alone book about Cixi’s artistic production is combined with the recent exhibition catalogue for Daisy Yiyou Wang and Jan Stuart’s Empresses of China’s Forbidden City,[6] to which Peng also contributed, Hui-shu Lee’s book on the artistic agency of Song dynasty empresses, and N. Harry Rothschild’s account of China’s only female emperor, Wu Zhao (624–705) of the Tang dynasty, the field of Chinese studies now has a relatively complete set of anchoring points for the study of imperial women as patronesses.

Notes

[1] As does the name of its invented author, “Aoh No! Mah toh péh.” As best I can tell with my rusty French, this is a pun mocking the sounds of Chinese language and corresponding to: “Ah non! Mon toupet,” which I will roughly translate (as rough as my English for the poem above; apologies to the French) as, “Oh no! My fringe.”

[2] As played by Lisa Lu (b. 1927), who portrayed Cixi on at least two earlier occasions in the successive Chinese language biopics The Empress Dowager and The Last Tempest (dir. Li Han-hsiang, 1975, 1976).

[3] Pamela Crossley, “In the Hornets’ Nest,” London Review of Books, April 17, 2014.

[4] Hui-shu Lee, Empresses, Art, and Agency in Song Dynasty China (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2010); Dorothy Y. Ko, Cinderella’s Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007); Yuhang Li, Becoming Guanyin: Artistic Devotion of Buddhist Women in Late Imperial China (New York: Columbia University Press, 2022); N. Harry Rothschild, Emperor Wu Zhao and Her Pantheon of Devis, Divinities, and Dynastic Mothers (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015).

[5] Jessica Harrison-Hall and Julia Lovell, eds., China’s Hidden Century, 1796–1912, exh. cat. (London: British Museum, 2023). Reviewed by William H. Ma in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 2 (Autumn 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.2.19.

[6] Daisy Yiyou Wang and Jan Stuart, Empresses of China’s Forbidden City, 1644–1912, exh. cat. (Salem: Peabody Essex Museum, 2018).