“Her Own Room Will Be a Picture”: Alva Vanderbilt’s Bedroom à la Pompadour at Marble House (1892) by Jules Allard et Fils

by Kedra KearisKedra Kearis is associate curator of art and visual culture at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library and affiliated assistant professor at the University of Delaware where she is a faculty member in the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture. She earned a PhD in art history from the Tyler School of Art and Architecture, Temple University, and an MA in literature from Eastern Michigan University. Her research specialties include transnational portrait style, revival interiors, and the history of collecting.

Email the author: kedrakearis[at]gmail.com

Citation: Kedra Kearis, “‘Her Own Room Will Be a Picture’: Alva Vanderbilt’s Bedroom à la Pompadour at Marble House (1892) by Jules Allard et Fils,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.1.3.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

The bedroom of US society leader Alva Vanderbilt (1853–1933)[1] at Marble House[2] in Newport, Rhode Island (1892), showcases a spectacular, French Revival[3] furniture suite crafted by the studio of French furnituremaker and designer Jules Allard (1832–1907) (fig. 1).[4] The nineteen-piece, pale gray ensemble includes a pierced scroll-back chaise lounge, a marble-top writing desk, velvet upholstered chairs, and a heavy, gilt-bracketed commode.[5] The largest and most visually imposing piece is a double bed ornamented with hand carving in high relief (fig. 2). Raised on a dais with a canopy that stretches sixteen-and-a-half feet, the bed nearly touches the room’s traceried ceiling. Its upward-sweeping lines lead to a soaring painting by the Venetian artist Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1675–1741) of Minerva in the heavens that appears to transcend the room’s architectural limits (fig. 3). Pellegrini was a painter patronized by European courts, and the placement of his work at Marble House signaled Vanderbilt’s ambitions to rival in status the great aristocrats of Europe’s Old World.

Vanderbilt’s bedroom furniture also reflected her taste for courtly furniture of the past. However, the furniture’s subtle shifts in ornamental vocabulary as well as its industrial construction reflected Allard’s modern attitudes and practices. Allard’s innovative approach to revival styles resonated with the forward-thinking Vanderbilt, whose family’s wealth was gained through the railroad industry. She challenged the conventions of Knickerbocker New York when, in 1883, she secured her position in society by throwing an extravagant fancy dress ball at her Fifth Avenue, French Revival château. Vanderbilt also defied the Victorian mores of old New York when she became one of the first in society to divorce her husband, William K. Vanderbilt (1849–1920), and vociferously sought to advance the position of women, using her wealth to support the women’s suffrage movement by hosting rallies at Marble House in 1909 and 1914.

Allard’s perspective on the past intertwined the taste for revival style with contemporary construction innovations that appealed to a modern client such as Vanderbilt, as Allard synthesized past and present in bespoke creations for each client and their desired space. Certain features of Vanderbilt’s bedroom by Allard follow baroque principles. For example, a diapered motif with florets adorns the headboard of the bed. The bed’s siderails also present rococo decorative elements, such as interlacing S-scroll and leafy-vine arabesques with dimensional, hand-carved rose blossoms. The bed’s design can be traced to a historic source: a print of circa 1702 (fig. 4) by Daniel Marot, the elder (1661–1752),[6] which was reproduced in the popular Dictionnaire de l’ameublement et de la décoration (Dictionary of furniture and decoration) (1884–87) by Henry Havard (1838–1921),[7] a book Allard kept in his library.[8] Yet, Allard took significant creative license in remaking the bed for Vanderbilt. His designs also reflect art trends and furniture creations by contemporaries such as Henri Auguste Fourdinois (1830–after 1894) (figs. 5, 6). Allard replaced Marot’s classical figures with two sea nymphs that coil up out of a watery realm. Rather than strictly adhering to eighteenth-century fashions, the nymphs sport chignons with a fringe of bangs and lively facial expressions that evoke the contemporary fashions of France’s Belle Époque (fig. 7). Allard’s emphasis on sea imagery further intimates the environment of late nineteenth-century Newport, the glamorous “city by the sea” that became the premier summer colony for the wealthy and powerful during the Gilded Age in the United States.

Allard carved out a significant place in the creation of Gilded Age furniture and interiors, though the designer and maker has received limited attention for a few reasons. Little documentation survives from his offices and workshops, and, unlike other makers of his time, Allard did not sign his furniture pieces, which has posed certain challenges to attribution. Paul F. Miller, curator emeritus at the Preservation Society of Newport County, has established Allard’s role as a cosmopolitan tastemaker and purveyor of artistic goods for a newly minted aristocracy in the United States.[9] This article aims to present Allard within an industrialized global market for luxury furniture and interiors during the Gilded Age. In focusing on Allard and his Marble House bedroom commission for Alva Vanderbilt, this study seeks to add to research on late nineteenth-century Parisian furniture, particularly the ways in which it conjured the past while also participating in a complex modernity—a subject worthy of more attention from scholars.

Allard tapped into a burgeoning global market for historically styled furniture and interiors through several strategies. In the 1880s and 1890s, he established satellite offices in New York (1885) and London (1895),[10] expanding beyond the Parisian clientele he inherited from his father, furnituremaker Célestin Allard (1807–54).[11] He pursued advantageous business partnerships, for example, collaborating with renowned beaux-arts architect Richard Morris Hunt (1827–95) to provide US elites with “Louis Room” adaptations of eighteenth-century French furniture and boiseries (carved-wood paneling).[12] He was reputed for salvaging old-master European ceiling paintings from Parisian townhouses and Italian villas, which lent an old-world mystique to newly constructed spaces. His arsenal of ancien régime paintings available to clients included versions of portraits of stylish eighteenth-century aristocrats and courtiers, such as an adaptation of Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour (styled as the goddess Diana), by the French artist Jean-Marc Nattier (1685–1766), which was listed in a sale inventory of 1907 after the death of Allard (fig. 8).[13] Additionally, while Allard wielded an ornamental language of the classical past, his business utilized the latest technological and industrial advances to meet massive market demands. Allard oversaw a large-scale industrial workshop of three hundred workers who performed taskwork using steam-powered machines.[14] Further, he promised to deliver complete room furnishings with speed. In order to meet the desired two-year production schedule for The Breakers in Newport, Allard promised Cornelius Vanderbilt II (1794–1877), the New York Central Railroad magnate and Alva Vanderbilt’s brother-in-law, that he and his workers would provide him with his furniture order “in a very short time” and that he could “entrust [Allard] with new rush orders,” a mode of rapid delivery that approached the prêt-à-meubler (ready-to-furnish) experience of a shopper in a modern department store.[15]

Using Alva Vanderbilt’s bedroom as a case study, this article will explore how Allard marketed his designs, seemingly paradoxically, as embodying the very best of the preindustrial past while embracing such industrialized and modern practices. In doing so, it will draw on material evidence produced by a long-term conservation survey of Allard’s furniture in progress at the Preservation Society of Newport County that began in December 2021.[16] Led by objects conservator Carola Schueller,[17] the Allard survey provides important information about the designer’s approach to construction and ornament, which made him a major figure in a global market for rapidly made, historicized French furniture and interiors. Lastly, this article will frame Allard’s complete room design of Vanderbilt’s bedroom as a tableau vivant (living picture) set within the context of Gilded Age performative culture. Allard and Hunt, the chief architect of Marble House, conceived of Vanderbilt’s bedroom as a performative space, as a tableau vivant of the eighteenth-century world of the French courtier Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, best known as the Marquise de Pompadour (1721–64), that would be animated by Vanderbilt’s own artistic, social, and imperial aspirations.

Reconstructing Alva Vanderbilt’s Bedroom à la Pompadour

Since its original staging in 1892, Alva Vanderbilt’s bedroom and its constellation of rooms at Marble House has been deconstructed and reconstructed, though the original layout was modeled after an eighteenth-century bedroom suite à la Pompadour. With the sale of the property to Frederick H. Prince in 1932, the bed was removed from Marble House, its hangings and bed textiles were packed away, and the bedroom space was converted to a sitting room. Following the acquisition of the house by the Preservation Society of Newport County in 1963, the room furnishings were reassembled and the original bed was located and reinstalled, although its canopy and dais had been lost. Using the cornice of an original but severely damaged wardrobe by Allard, Preservation Society staff improvised the baldachin and installed it as it currently appears (see fig. 1). They also rebuilt the dais, which Vanderbilt’s daughter, Consuelo Vanderbilt-Balsan (1877–1964), recounted in her memoirs.[18] As it stands now, the connecting space between Vanderbilt and her daughter’s rooms is dedicated as a trophy room in honor of Harold S. Vanderbilt (1884–1970), containing a display of his yachting memorabilia. An attempt at reconstructing this space suggested that Vanderbilt’s bedroom suite likely included a dressing room and boudoir, a type of room made popular by Pompadour herself.[19]

Pompadour, who was an art patron and society leader as well as aide and advisor to King Louis XV (1710–74) and his cosmopolitan court, held a particular appeal for ambitious women of the Gilded Age like Alva Vanderbilt.[20] In the nineteenth century, newly made women like Vanderbilt admired Pompadour not only for the artistic and social realms she commanded but also for her self-fashioning agenda via portraiture and theatrical tableaux vivants that transformed her image from bourgeois to aristocrat. Writing in the late nineteenth century, the Goncourt brothers, Edmond (1822–96) and Jules (1830–70), contributed to the idealization of Pompadour, devoting pages of writing to her in their biography Madame de Pompadour (1888) and in their volumes on the eighteenth-century artists who painted her image.[21] By emulating Pompadour through portraiture and interiors, nineteenth-century American arrivistes sought a similar status transformation from bourgeoisie to new aristocracy through channeling her mode of self-fashioning.

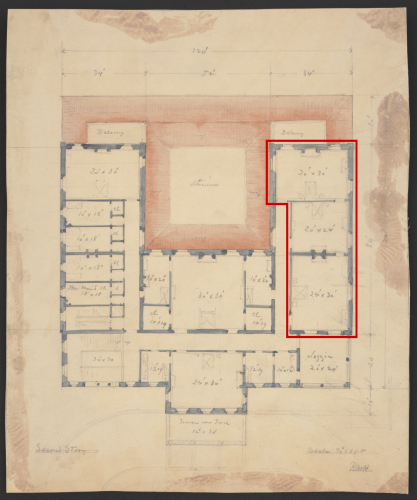

The plans and drawings produced by Hunt for the second floor of Marble House provide insight into the use of the space from the outset as well as establish a Pompadour stylistic agenda developed further by Allard.[22] The varying plans for the second-floor layout each contain key elements of the final execution, but none presents a clear and complete roadmap. One drawing indicates a communicating door to the right of the mantel wall of Vanderbilt’s bedroom that likely led to a dressing room and boudoir space (fig. 9). Labeled “Second Story” and signed “RMH,” the drawing shows an expanded plan extending street side. Moving beyond the extended space, the three rooms that flow west reveal a closer vision of the 1892 view of the bedroom suites of Vanderbilt and Vanderbilt-Balsan. There are corresponding fireplace mantels on either side of the adjoining wall between the room labeled 24' x 30' and the room labeled 20' x 24'. The drawing also shows communicating doors joining those rooms and another door leading to the room labeled 20' x 30' on the eastern right corner of the house.[23] In establishing the connectivity between the two bedrooms through intermediary spaces, an elaborate eighteenth-century conception of the space emerges that includes a Pompadour-type boudoir. For the eighteenth-century woman, according to French literary scholar Joan DeJean, the boudoir constituted “the ultimate interior room” and “the archetypal room of one’s own.”[24] While no architectural plan labels a room as a boudoir, Vanderbilt refers to the room in her memoirs: “There is a life-sized marble bust of a young girl done by [French sculptor Augustin] Pagou [sic] on the mantel of the boudoir.”[25] Some have assumed the ladies reception room on the mezzanine to be the boudoir, yet the public nature of this location and its use by guests to Marble House do not equate with the concept of a private, inner room attached to a bedroom.[26] Additionally, the small mantel in the reception room would not feasibly hold a bust the size of typical works by Augustin Pajou (1730–1809).

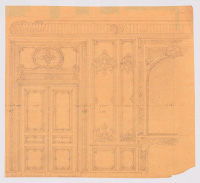

Another drawing by Hunt illustrates concepts for the mantel or east wall of Vanderbilt’s bedroom and reveals not only a communicating door but, more importantly, a theme related to Louis XV and Pompadour (fig. 10).[27] The sketch depicts one of a pair of double doors to the left of the wall axis, with the symmetrical pair to the right omitted. It also includes a large picture frame or mirror containing a centrally placed figure clearly based on the Marquise de Pompadour, from the iconic Maurice-Quentin de La Tour portrait (1753–55) at the Musée du Louvre (fig. 11).[28] Visible in Hunt’s drawing are the unmistakable attributes of La Tour’s rococo portrait d’apparat (ceremonial portrait): a finely carved fauteuil, a gilt bureau with a convex shell, volumes of the Encyclopedia edited by Denis Diderot (1713–84) and Jean d’Alembert (1717–83), and a globe. This public-facing portrait contains objects that signal Pompadour’s vast contributions to the decorative arts and the cultivation of knowledge in France as well as her imperial influence as a powerful confidant of the king in matters regarding global affairs. The shape and decoration of the sketched dress in Hunt’s version echoes La Tour’s portrait of Pompadour as well.

In one important detail, however, Hunt’s Pompadour sketch departs from the La Tour portrait: the sitter’s hair. Rather than Pompadour’s loosely styled tête de mouton (sheep’s head), a popular hairstyle in France in the 1850s with curls in rows around the face, Hunt describes a mass of curls cascading to just beneath the figure’s shoulders. This hairstyle strongly resembles Vanderbilt’s curled locks in her own most iconic portrait, the photograph taken by José Maria Mora (1849–1926) on the occasion of the Vanderbilt Fancy Dress Ball in 1883 (fig. 12). The drawing, therefore, evokes not exactly Pompadour but Vanderbilt in performative dress in the role of Pompadour.[29] The image can be seen as the reflection of Vanderbilt observable in an inset ornamental mirror. That is, rather than a painted picture in a frame, the drawing describes a framed mirror. Therefore, through Hunt’s visualization, the viewer regards Vanderbilt herself in reflection seated within the projected space of her Pompadour-styled bedroom. Placing her at the marble-top writing table in the center of the bedroom, Hunt has added a vertical extension to the background of the La Tour pastel to account for the height of the Marble House bedroom. Hunt envisions this Louis XV bedroom as a performative space where Vanderbilt fashions herself as the eighteenth-century Pompadour, establishing a collaboration between patron and architect in constructing the self-portrayal, in the form of a tableau vivant that this room will become.[30]

Allard fully realized the theatrical environment that bolstered Vanderbilt’s performance as Pompadour. In his final execution of the room, he followed, but also modernized, Hunt’s conception. A second drawing by Hunt of the same wall shows the addition of a mantel with caryatid figures and a mirror (fig. 13). Allard animated and electrified this vision with his sculptural hand and modern sensibility, transforming Hunt’s classical caryatids into more prominent, three-dimensional Belle Époque figures holding candelabra wired for electricity (fig. 14).

Allard may also have chosen or advised Vanderbilt on the selection of the mauve textiles in her bedroom, which signaled his looking to Pompadour in the past as well as toward current technologies of the 1890s. The purple dyes appearing in the wall coverings, bed textiles, and upholstery were innovations developed at the Pompadour-sponsored Sèvres porcelain factory during the 1700s.[31] Additionally, the use of mauve points to color experimentations from the 1850s.[32] In the late nineteenth century, the color mauve was equated with haute couture, a phenomenon resulting from developments in industrial dye processes.[33] Allard’s and Vanderbilt’s involvement in the selection of heliotrope, a variant of purple, can be traced through the records of Lyon-based textile company Prelle, which indicate that samples were ordered on May 24, 1890, followed by a swift order exactly one month later. This rapid timeline suggests that Vanderbilt was consulting with Allard in Paris and was present to approve the color. Developed in 1856 by British chemist William Perkin (1838–1907) from extracted coal tar, the dye used by Prelle was known as Perkin’s mauve. Its development and use in France in the late 1850s and early 1860s resulted in the phenomenon called the mauve decade.[34] French Empress Eugénie (1826–1920) was cited in 1859 in London’s Punch as a sartorial leader in France for wearing mauve,[35] and she appeared in an equestrian portrait in 1856 by Charles Edouard Boutibonne (1816–97) and John Frederick Herring I (1795–1865) wearing the same hue (fig. 15).

A variation on the mauve color used in the Allard bedroom suite appears in a portrait of Vanderbilt as Diana from after 1884 (fig. 16). Vanderbilt recollected how the portrait once hung in the Morning Room[36] of Marble House; it is now in the collection of the Historic Mobile Preservation Society in Alabama.[37] The picture, by US portrait painter Benjamin Curtis Porter (1843–1908), engages with the classical-revival mode of the fin de siècle, while specifically evoking Pompadour styled as Diana in the portrait of 1746 by Nattier (see fig. 8). Just as Pompadour costumed herself in a guise from antiquity, so does Vanderbilt channel the goddess of the hunt. With a half-moon diadem crowning her head and her famous pearls that formerly belonged to Catherine the Great sweeping across her chest, Vanderbilt’s portrayal exemplifies a popular fashion in transnational portraiture of the 1880s and early 1890s. The Diana theme became especially fashionable as Marble House was being completed in the early 1890s, following the mounting of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s (1848–1907) Diana (1892–93; Philadelphia Museum of Art) on the second Madison Square Garden building designed by architect Stanford White (1853–1906), which opened in 1890. The shades of Vanderbilt’s classical-style cloak appear distinctively mauve compared to the pink of her cheeks and of the contouring on her shoulder. Importantly, although scholars have often dated the portrait earlier, it was most likely painted within a few years of the completion of Marble House. Porter entered the circle of Alva and William. K. Vanderbilt[38] with the first portrait commission of their son around 1884.[39] The Porter portrait provides further evidence for Vanderbilt’s multilayered self-styling within the home’s theatrical spaces. Her presentation as the goddess Diana within the public space of the Morning Room, done in the style of Louis XV, reinforces the Pompadour-era style agenda of the private space of her bedroom. As one performative scene unfolding upon the next, the house and its decorations serve as the ideal setting in which to hold “court.”

“De ma main” (By My Hand): Jules Allard between Art and Industry

Just as Vanderbilt self-fashioned as Pompadour, the Portrait of Jules Célestin Allard (1889) by the French artist Fernand Cormon (1845–1924), in the collection of the Preservation Society of Newport County, depicts the designer in self-fashioning mode. Surrounded by the luxury items of a genteel negotiator of cosmopolitan style, the portrayal presents other signs of Allard as a hardworking, industrial maker (fig. 17). Placed close to the front of the picture plane, the sitter draws the viewer into his confidence. Seated in a Louis XIII chair at a Louis XV bureau plat, both likely Allard creations, the designer speaks directly to the viewer, his lips parted and eyes twinkling over the prospect of new clientele. The Légion d’honneur (Legion of Honor) ribbon fastened to his coat lapel recalls his success at the Paris World’s Fair of 1878 that brought him a gold medal. The ribbon and his choice of Cormon to paint his portrait tie him to the Opéra Garnier sculptor Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse (1824–87), who was previously painted by Cormon wearing the same Legion of Honor ribbon.[40] The desk’s rich gilt moldings, with precisely carved serpentine edges, seem to wrap around the hand of the maker, which appears large and foregrounded. The outsize hand underscores Allard’s position as a craftsman as well as a cosmopolitan sophisticate. Exhibited at the Paris Salon, which was held concurrently with the Paris World’s Fair of 1889, the painting presented Allard to the public as a gentleman-maker.

Today Cormon’s portrait presents signs of editing and signs of areas painted over, perhaps in the days leading up to the Salon. The pose depicts Allard with one hand conspicuously raised and partially closed and the other hand with somewhat elongated fingers fanning out from an arm with its wrist firmly planted on the desk. It is conceivable that there was formerly a cigar painted in Allard’s left hand and a glass of libation in the other, and that these were painted over by Cormon in extraordinary circumstances just prior to the exhibition. The pentimenti remain visible, fine traces of white highlights that formed the glass in his right hand.[41] One month before the May exhibition of the portrait at the Salon, Allard’s name had been splashed across the pages of US newspapers attached to accusations of smuggling art objects inside cabinets and other items of furniture for elite patrons, including William K. Vanderbilt.[42] With tax-fraud allegations leveled against the designer, Cormon may have painted out objects depicting Allard as well-to-do, living off ill-gotten gains from undeclared imports. Cormon’s covering over the maker’s signs of success leaves the left hand, with space between the fingers where the cigar was painted out, with no set activity attached to it, except to lean on a desk of his own making. The viewer is left with a picture of a maker and purveyor of luxury objects rather than a consumer of those objects.

Contemporary critics of the Paris World’s Fair of 1878, the show that garnered Allard accolades, framed his works within a salient period debate of art versus industry, of hand versus machine.[43] The fair was a venue for showcasing the technological advancements of France in all areas of art and industry, furniture included. At the same time, the critical reception of both the luxury and the affordable furniture presented that year revealed a deep anxiety over the potential loss of the heritage of French artistry when it was faced with the threat of mechanization. Commentaries about Allard specifically emphasized his hand as a fine sculptor and also his hand enhanced by machines, resolving potential conflict between them. This rhetoric of Allard’s artistic hand, picked up by more than one critic, undoubtedly carried over into Cormon’s portrait of Allard more than ten years later at Marble House.

French critic Émile Bergerat, reporting on the 1878 fair, railed against the latent fears over lost heritage, citing Allard’s hand and comparing it to that of French Renaissance sculptor Jean Goujon (1510–65): “the artist’s figures of Painting and Sculpture seem to have come from the hand of Jean Goujon.”[44] The nineteenth-century romanticization of the Renaissance underpins this comparison and places Allard, the industrially trained cabinetmaker, in the lineage of great French sculptors.[45] Diane de Poitiers visitant l’atelier de Jean Goujon (Diane de Poitiers Visiting the Studio of Jean Goujon) by French painter Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard (1780–1850) portrays France’s artistic rebirth as a means of shaping a narrative for a French national style in the nineteenth century (fig. 18).[46] The image illustrates the moment when Goujon has laid down his mallet after the creation of his masterpiece La Diane d’Anet, in which he styles Diane of Poitiers (1500–1566), mistress to French King Henry II (1519–59), as the classical goddess of the same name. The fingertips of Goujon’s left hand just graze his draped worktable, while his right hand holds the sculptor’s chisel. Light streams through a window at the upper left, highlighting parts of the sculptor’s finished product and fully illuminating the model, Diane de Poitiers, in a suggestion of the divine inspiration of Goujon. Through such narrative associations, Allard’s hand was aligned with France’s great artists of the past, while his artistry, which was assisted by industrial acumen, was emphasized elsewhere.

An unnamed critic from Le Panthéon de l’industrie insisted in 1879 that Allard’s worth rested upon both his artistic mind and his hand guided by the machine:

From his magnificent workshops, where there are legions of draftsmen, modelers, sculptors, he was careful not to exclude the simple cabinetmaker, carpenter, turner and upholsterer; he introduced, with jealous eagerness, the most perfected machine tools; he put them into action by a powerful steam engine, recognizing that if only the hand guided by intelligence and taste can handle wood, chisel it finely, make it live, no hand can [do precise construction work] as well as a machine, cutting the material, planing it, slotting it, turning it and polishing it.[47]

The passage emphasizes Allard’s status as master of the workshop, guiding the many hands of the Maison Allard’s industry. However, “no hand can [do precise construction work] as well as a machine.”

Allard’s industrial capabilities, combined with his assurance of artistic merit, appealed to his clientele of industrial elites. He gained their confidence through a constant reassurance that his artistic hand was behind the creations of the Maison Allard and that his firm business hand was guiding the house. Though his sons and agents sent updates from time to time, Allard himself handled the correspondence with premier wealthy buyers. His handwriting and signature appeared on solicitations for business, requests for meetings, design proposals, and even detailed information about shipments of goods.[48] He even promised his signature as a nonnegotiable marker on one occasion. In June of 1887, Allard wrote to New York real estate baron Ogden Goelet (1851–97) regarding payment for design work, adamantly insisting that Goelet should wait for Allard’s signature on the bill. “I will present you a receipt signed by my hand,” he wrote,[49] demonstrating the unswerving control he sought over his house’s business affairs and his willingness to share that fact with his clients.

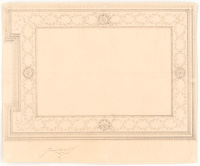

Allard’s signatures as a designer and maker reveal that he prioritized certain media for signing, which provides insight into his self-conception vis-à-vis his clientele. His penned signature on correspondence resembles his signature on the few of his designs that survive. A design for the ceiling of the Ladies’ Reception Room at The Breakers, for which Allard provided the interior design and furniture suite, bears his signature (fig. 19). Allard did not sign his furniture creations, perhaps reflecting his dealings with private clients and galleries; makers supplying department stores were more likely to stamp and sign their pieces.[50] The creations Allard did sign were rather permanent house installations placed in prominent locations, ranging from the faces of clocks and barometer pendants to garden sculptures and sculptural reliefs.

Unlike a piece of Allard furniture that has been handled by any number of craftspeople, Allard’s unique sculptural works came directly from the hand of their maker. For example, the base of the newel post of the grand staircase at Marble House presents a mold stamp with the words “J. Allard et Fils” in block letters, shaped not unlike those used in a typical furniture stamp. Attached to the massive wrought-iron stair railing designed by Allard, the post stands in direct view upon entering the foyer. Its high visibility and permanent placement point to Allard as a major contributor to the mansion’s interior design. Though the role of furniture in the staging of these interiors was paramount, the suites and individual pieces were moveable, subject to breakage, and could ultimately be sold off and thereby removed from their intended setting.[51] The immovable ornamental and sculptural features of the house are permanent homages to Allard the designer and sculptor.

A similar stamp, containing the words “J. Allard & Ses Fils” in block letters, appears on an overdoor relief at The Elms, the Newport home of industrialist Edward J. Berwind (1848–1936) and his wife Hermione (fig. 20). Its placement in an equally important location, the entrance to the ballroom from the Grand Foyer, signals Allard’s leading role as interior designer. His signature is placed just near a putto’s hammer (representing Allard’s artistry as a sculptor) and anvil (representing the industry of cabinetmaking), a playful suggestion of the mythical source of the “chiseled” signature (fig. 21). Allard’s use of a furniture-style stamp in this overdoor and on his sculptural molds in general call to mind his cabinetmaker identity, reminding the viewer that his status as a sculptor and furniture designer are united in his industrial-art persona.

Findings from the Allard furniture survey[52] at the Preservation Society of Newport County illustrate further this tension between hand and machine—between the precision of industrial machines and the unique irregularities of the hand. Allard’s workshop approach was one that combined steam-powered tools in the preparatory stages of production with artistic hand tools in the finishing stages. In the example of the double bed in Vanderbilt’s bedroom, which was a standard bed construction for the 1890s, the frame, prepared by steam-powered tools, takes on new dimensions with the massive, hand carved figures on the headboard and footboard. Additionally, the roses along the sideboards present fully dimensional, high-relief carving made possible only through the use of hand tools. In comparing four seemingly identical side chairs made for the suite, the tool marks that are the evidence of hand carving are clearly visible, as are the idiosyncrasies of the hand-tooled ornaments (figs. 22, 23). Notably, the flower petals in each example vary ever so slightly in shape and placement, their irregularities affirming the handcraftsmanship of each individualized piece. Vanderbilt’s bedroom, designed by Allard the industrial artist, demonstrates the value of both hand production and machine production in the details of its carved ornaments and in the precise, durable construction made possible by steam-powered tools.

What is clear is that Allard’s efficiency in delivering furniture orders to clients depended upon a large staff of workers using an assembly-line approach to production. In a letter of 1894 from Allard to Vanderbilt’s brother-in-law Cornelius Vanderbilt II concerning work for The Breakers, he reveals that Allard et Fils was three hundred workers strong.[53] The submission forms for the furniture section of the Paris World’s Fair of 1878 offer further insight into a large group of makers, revealing the number of workers employed at various tasks in each shop, the type of machines at a given firm, and the degree of steam power utilized.[54] Because of the long-standing participation of its workshop in international fairs, Allard et Fils was not required to disclose this information in the registration for the event.[55] Nonetheless, the forms filled out by comparably sized exhibitors provide helpful insight into Allard’s shop practices.

The completed submission forms from 1878 for workshops of a size similar to Allard’s indicate that he had access to a vast number of steam-powered machines used by makers of both luxe (luxury) and à bon marché (affordable) furniture. The submission form of Félix de Fallois, a luxury-furniture maker with three hundred workers and a close match to Allard’s quality and scale, indicates that the following machines were in use in his workshop: a tenon machine running at fifteen hundred turns per minute, a mortise machine at two thousand turns per minute (at three horsepower), a trimming-and-drilling machine at fifteen hundred turns per minute, and a molding machine at five thousand turns per minute.[56] Also, Garrett-Cox and Schueller’s survey from 2022, which includes Vanderbilt’s bedroom at Marble House, found toolmarks from a mechanical planer visible on the underside of the suite’s nightstand as well as toolmarks from a fine-toothed, mechanical fretsaw visible on the backside of the apron (fig. 24).[57] The survey also found hand-tooled scribing and saw marks on the dovetailed drawers to the suite’s commode (fig. 25). With its large, gilded mounts, precious woods, and high-relief carving, the commode is one of the showpieces of the room, rivaled only by the double bed (see fig. 1). The hand-tooled elements of the commode’s framework likely would have given it a higher perceived value than a similar piece made entirely by machine, placing it on caliber with furniture made by the illustrious eighteenth-century French cabinetmakers of the past. Another way Allard presented his furniture as high caliber was by applying expensive finishes. For example, he frequently made use of gildings that he called “old gold,” applied to a new piece of furniture to make it look old and costly.[58] Through these methods, Allard distinguished himself from affordable furniture makers with the promise of hand-carved ornament, high-quality woods, and costly finishes.

Allard’s Design Empire: Sourcing the Past in the Contemporary

While there is no extant correspondence between Vanderbilt and Allard for the design of Marble House’s interiors, other correspondence between Allard and his clients proves useful for understanding the artist’s design process at Marble House. Exchanges with clients regarding designs would include sketches, physical examples of ornamental moldings, fabric samples, and cost estimates, as well as follow-up conversations to adjust plans according to a client’s tastes. Notably, Allard would identify a key design motif or motifs around which a room’s conception would unfold or a centerpiece(s) for the furniture suite that would lead the design organization. These motifs were sourced either from celebrated designs by contemporary designers or from the ornamentation on examples of historical furniture.[59] In the case of a summary bill of 1887 for the bedroom of Ogden and May Goelet’s daughter, Allard lists the design centerpiece for the suite first: a Norman two-tone lacquered armoire with painted lovers inset in the door panels.[60] Next, he lists the remaining suite items: a bed, commode, and chairs, each preceded by the word “matching.” Allard’s bill for the bedroom of Mrs. Goelet follows the same framework, with the bed as centerpiece and the remaining furniture pieces described as matching. This method reveals Allard’s close attention to creating a harmony of materials, ornament, and style in his designs for furniture suites.

Allard also worked with complete room furnishings, harmonizing the furniture suite with its corresponding interior, utilizing motifs from a classical past placed in conversation with contemporary cultural trends. The trellis motif on the walls of Vanderbilt’s Pompadour bedroom, a form of fine tracery with interlocking florals, is an example of a motif that functions in harmony with the furniture suite. The trellis repeats across the stucco ceiling, affirming its importance in the ornamental harmony between the furniture and the rest of the interior (fig. 26). It reappears in multiple formats, carved into several surface areas of the bed frame and on the pierced back splat of the velvet-upholstered light chair (fig. 27), where it rhymes with the embroidery design on the upholstery of the seat. Like other ornamental motifs used by Allard, the trellis evokes the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in France, in particular the decorative trellising of the garden follies at Versailles.

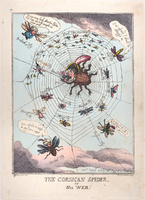

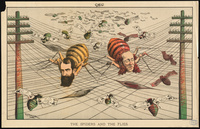

But the trellis motif also takes on more varied shapes, evoking contemporaneous uses of the spider web in the popular imagery of empire building. While the web motif dates back to antiquity in its association with the web of the ill-fated weaver Arachne, spider webs took on new meanings in the nineteenth century, when they were ubiquitous as representations of empire. Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) appeared as a spider in a British caricature of 1808 titled “The Corsican Spider in His Web!” (fig. 28). With the words “Unbounded Ambition” written across his arachnid belly, his mouth opens to devour flies, while a fly labeled “Turkish fly” declares, “I am afraid it will be my turn next.” The image reflects the conflict of the Napoleonic wars but also Napoleon’s colonial conquests in the Middle East and North Africa as he built his empire. Caricaturists of the Gilded Age took up the spider web as well to depict the industrial robber barons and their “webs” of crisscrossing railroad tracks and telegraph wires, the means of building industrial corporations on an imperial scale and a phenomenon that coincided with US expansionist agendas of the late nineteenth century. In an editorial cartoon by Charles Kendrick titled “The Spiders and the Flies,” telegraph magnates Jay Gould (1836–92) and William Henry Vanderbilt (1821–85) appear as spiders weaving their competing webs of empire, featuring the telegraph wires of the American Union and Western Union Telegraph companies (fig. 29). Not only does the image take a jab at the wealthy business tycoons dominating the telegraph industry; it also shows Gould and Vanderbilt climbing the wires at a height above the city, an analogy for their high financial and social standing. But webs could have positive connotations as well. In her memoir, Vanderbilt referred to “the old Commodore,” her husband William K. Vanderbilt’s grandfather, as a financier with a web-like vision: “He saw that the future of this vast country lay in Railroad Development. In vision he saw the web of steel which has since become the New York Central System and he set about weaving it.”[61] The spider’s web as a metaphor for the telegraph and the railroad lay within the imagination of Vanderbilt, and its presence in her bedroom ornament tied the classical past with such contemporary imagery and an understanding of her own family’s industrial empire.

The web ornament throughout the Pompadour-style bedroom further connects Vanderbilt to images of empire associated with the Marquise de Pompadour, the unofficial “queen” of Versailles. In the painting Sultana Drinking Coffee (1755) by French artist Carle van Loo (1705–65), Pompadour appears in Middle Eastern costume as a sultana with a Black woman in attendance (fig. 30). Reflecting the fashionable trend to appear à la Turque (in Turkish style), this and other such images expanded the “empire” of women at the French court to include the colonial reach of the realm, emphasizing differences in skin color as well as perceived cultural differences.[62] Likewise, Vanderbilt extended her New York empire to that of Newport, conquering the social scene by way of her Marble House building project. While the house was under construction in 1889, she also traveled to the Mediterranean, extending her reach to Egypt where she was photographed before the Great Sphinx of Giza (fig. 31).[63] With her daughter seated at her feet, her pale face framed by a plumed black hat, and her gloved hands clutching a black parasol, Vanderbilt squints in the sunlight reflecting off the sand. Her figure stands in contrast to the translucent backdrop that is the desertscape of the Valley of Giza. The image’s faded background layers lend a surreal, almost staged quality to the photograph, though the sand under the feet of the subjects betrays that this is in fact Egypt. Later, in 1893, Vanderbilt traveled to British colonial India,[64] where she was photographed on an elephant (fig. 32). Seated in a carriage on the elephant pictured second from the right in the photograph, she shoots an inquisitive look at the photographer from her position high above the ground. These photographs and the frequent travels of Vanderbilt suggest her active, restless nature and her desire to explore and expand her reach beyond the United States and Europe.

Staging Marble House in the Age of the Department Store

Key to the expansion of Vanderbilt’s influence was realizing the massive artistic setting of Marble House, conceived of as a performative site for staging her extensive power. Its construction saw the importation of raw materials from abroad on a sizable scale. Allard’s complete room furnishings were crated and shipped by freight from Paris. With Hunt and Allard at the helm, antique furniture and the designs for new creations were sourced in Paris as well. The design for Vanderbilt’s bed, the room’s pièce de résistance, was discovered on one of her shopping trips for art and furnishings coinciding with the Paris World’s Fair of 1889. That a design model for the bed was displayed in the public space of an industrial fair and was placed on a platform for ease of viewing blurs the line between public and private modes of consumption.

In his meditation upon the Paris arcades as symbols of a lost era, German philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) points to a self-fashioning that occurs within the performative space of one’s own home where the normative bounds between public and private are blurred, a reflection of the commodity culture born out of the massive displays of the Paris World’s Fairs.[65] Benjamin cites the Paris World’s Fair of 1867, the crowning display of the Second Empire’s material achievements, as the apex of such phantasmagoria. The circulation of fantasy interiors increased rapidly in the second half of the nineteenth century, first through the channels of world’s fair displays and department store displays and their print media, then through interior-design plates in the form of printed books and trade catalogues. Beginning with London’s Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851, the style of arranging goods at fairs started to have a significant impact on displays in the emporia of the department store.[66] The printed images of domestic interiors in the 1870s and 1880s favored historical styles labeled as such, but they also distinguish the pure “fantasy” interior, which defied description with a single revival style. Art and design historian Anca I. Lasc explores the phenomenon of circulating interior designs depicting “interior dreamscapes” and identifies the private home in the nineteenth century as a stage for the display of such fantasy rooms.[67] Decorative painter Georges Rémon (1889–1963) distinguished between a bedroom in the style of Louis XV and a “fantasy” bedroom in his Intérieurs d’appartements modernes (Interiors of modern apartments) (ca. 1892; figs. 33, 34).[68] A fantasy bedroom defies the superficial decorative motifs associated with specific revival styles. With its blend of Louis-style ornaments and overarching Pompadour styling, Vanderbilt’s private bedroom spaces at Marble House emerge as a fantasy suite, a phantasmagoria.

There was another, equally famous marble building constructed during the Gilded Age: dry-goods merchant Alexander Turney Stewart’s (1803–76) Marble Palace department store in New York City (fig. 35), which has been long overlooked in scholarship on Vanderbilt, though it captured her imagination.[69] In her memoirs, Vanderbilt highlighted her father’s friendship with Stewart, which developed upon her family’s move to New York City in 1859 or 1860 when she was six or seven years old.[70] Vanderbilt even set the record straight when she noted that Stewart’s Marble Palace predated the opening of Aristide Boucicaut’s (1810–77) Bon Marché department store in Paris in 1852,[71] emphasizing that the Marble Palace was therefore not only the first department store in the United States but “the first in the world.”[72] Vanderbilt defends Stewart against his critics, lauding his democratization of luxury goods for the lower classes and stating that he provided them “an opportunity to purchase things then available as a rule at prices beyond their means.”[73]

The appearance of the Marble Palace set a new standard for large retail establishments. Stewart started his business in 1823 as a small-scale draper, boasting innovations in Irish laces. In a city filled with red-brick facades, Stewart eventually expanded his operation into a new building fronted with Tuckahoe marble at 280 Broadway, on the northwest corner of Broadway and Chambers Street in New York City.[74] The Italianate marvel was built between 1845 and 1846 by New York architects Joseph Trench (1810–79) and John Butler Snook (1815–1901) and was quickly dubbed “the Marble Palace.” Decades later, newspapers frequently called Vanderbilt’s Newport mansion “the Marble Palace” when word had spread that it was to be constructed in marble, suggesting that commentators were drawing a connection between Marble House and Stewart’s iconic department store.

The public’s desire for information about Marble House rivaled Vanderbilt’s intense efforts to conceal the plans and designs for the home, at least initially. After the family’s purchase in 1888 of the Bellevue Avenue property then known as Fern Cliff, the future site of Marble House, Vanderbilt had insisted upon strict secrecy regarding the construction and the interior designs of Marble House.[75] The Newport Mercury related that a reporter from Frank Leslie’s Magazine had disguised himself as an electrician in order to enter the Marble House property while it was under construction. “Armed with a coil of wire, gimlets and kodak,” the reporter allegedly “entered the grounds and in a twinkling of an eye had the representation of Marble Hall indelibly impressed upon the photographic negative.”[76] On May 9, 1892, Newport’s Observer released an exclusive report on Vanderbilt’s mansion titled “The Marble Cottage,” with the subtitle “First Published Description of Mr. Vanderbilt’s Villa; A Masterpiece of Construction and Decoration by Some of the Greatest Artists.”[77] While it appears that the Observer’s article was the first full account of the mansion’s interior spaces, information about Vanderbilt’s bedroom was lacking. The Observer reported the following:

Suffice it to say, that the carloads of furniture are now arriving to be unpacked and shortly the mistress herself will be here to adjust the pieces. Her own room will be a picture. A model of the apartment was set up before the Parisian connoisseurs in the salon there and was awarded the first prize.[78]

As previously demonstrated, Vanderbilt’s “own room” was transformed into a picture, a tableau vivant, through the imagination of the architect and the interior designer. While this article of 1892 does not reveal the design of Vanderbilt’s bedroom at Marble House, we do learn that there was a model of the bedroom suite on display at the Paris Salon.

However, as noted above, the Paris World’s Fair of 1889 featured a furniture display, though it did not include Allard’s bedroom furniture. We do know that Vanderbilt was in Paris in time for the Longchamp races held in July of 1889, which she attended with her husband William. This suggests that she might well have visited the fair, which had opened in May. In fact, she was at the races with the architect Hunt and his wife Catherine Howland Hunt, who noted that Vanderbilt had traveled to Paris “in order to arrive at certain decisions for the interior of Marble House.”[79] One aim of Vanderbilt’s trip was to find an art collection and furnishings for the Gothic Room at Marble House. While there is no known correspondence to prove that Vanderbilt was meeting with Allard in Paris at this time in 1889, it is feasible that she would have consulted with her choice decorator about a certain bedroom-furniture suite she would have seen at the fair.

In a review of the Paris World’s Fair of 1889, Havard cited a bed on a dais designed by Fourdinois for the furniture house of Schmitt as one of the two best pieces in the show (see fig. 5).[80] While the bed differs in ornament from Vanderbilt’s, its Renaissance Revival style, its dramatic presentation on a raised dais with an open canopy, and its large tiebacks on the curtains make a strong argument for it being the model Vanderbilt desired. In addition, Fourdinois had produced a related bed in 1867 (see fig. 6), which garnered much praise at that year’s Paris World’s Fair.[81] Though it lacks the dais of the 1889 creation, it features similar sea nymphs with coiling tails like those on Vanderbilt’s headboard. Allard combined these contemporary design sources by Fourdinois from 1889 and 1867 with the design by Daniel Marot from Havard’s Dictionnaire, resulting in a bed that evokes the overarching Pompadour theme of the bedroom.[82] The drawing of 1889 of the Fourdinois bed emphasizes its show presentation, raised on a dais according to fashion, but also raised on a sale platform in the context of the furniture display at the World’s Fair. The modes of display in this and other international fairs mirrored those of the department stores, and vice versa. Reflecting a department store window display or showroom display, the world’s fairs incorporated interior design elements that curated furniture and interiors for the public. By 1900, the major Paris department stores had their own floor spaces at the fair, further blending the industrial aspects of the fair with the products offered by department stores for furnishing private spaces. Therefore, in the public presentation of the Fourdinois bed and in the private presentation of Vanderbilt’s bed, sale platform and dais merge, blurring the line between the public and the private.

Vanderbilt made the decision to open Marble House to the public in 1909 to draw attention to the women’s suffrage movement. In August of that year, she hosted suffrage lectures on the property of Marble House, offering tickets to see the house’s interiors, though the bedrooms and private spaces of the second floor were not on display. Without a doubt, this added to the mystique of her long-discussed bedroom, a model of which had once graced the platform of the furniture-section display at the Paris World’s Fair of 1889. In this case, the fantasy bedroom remains an imagined one, with word of mouth and newspaper reports enhancing its prestige and increasing its perceived, if incalculable, value.

Furthermore, Allard’s approach to working with clients aligned with the department-store mode of visual display and consumption. Allard’s prêt-à-meubler mode of working proved attractive to his elite US audience, for whom speed and accuracy of production went hand in hand with stylistic aplomb. Building and furnishing a luxurious revival-style mansion established the ideal setting for an elite socialite such as Vanderbilt to place her wealth on display and play the part of a modern Pompadour, a cultural and artistic tastemaker of her own social empire.

Conclusion

The collaboration of Hunt and Allard on Vanderbilt’s Pompadour-themed bedroom affirms the fact that the architect and the designer understood the needs of their mutual client and firmly grasped the ethos of the performative culture in which she was fully immersed. Vanderbilt’s self-portrayal as Pompadour through a revival interior setting resulted in a pictorial living space that suited her energy and ambition for building her empire. The fantasy creations of Allard within the context of a global market for furniture appealed to a US clientele who urgently sought period furniture and interiors with an original flair. His workshop’s modern equipment, installed in a large, industrialized setting, allowed the artist to tailor furniture suites to interiors with remarkable speed and artistry. Allard’s assurance of his artistic hand, guided by the precision of machinery, spoke to Vanderbilt’s own appreciation for old-world artistry and industrialized innovation. His visual lexicon met the demand for period furnishings that could be tailored to the requirements of a self-fashioning arriviste in the United States, building her social and artistic empire through luxury furnishings and interiors. An Allard piece or room[83] was made in France and recognizably pedigreed, rooted in historical styles while maintaining an imaginative and up-to-date flair. Allard’s manner of combining design sources from the past with his original ideas formed the basis for his theatrical, furnished, fantasy interiors like Vanderbilt’s Pompadour bedroom suite. The display of the room’s bed in the public arena of an industrial fair further underscored the blending of art and industry, public and private, and designs indicative of past and present.

Ostensibly, Allard’s successful global enterprise resonated with his US industrialist clientele, and his self-presentation was an important aspect in this regard. His cosmopolitan outlook meant that he understood his clients’ desire for luxury goods made in France and could satisfy their taste for old-world style. Allard’s “corporation” of design elements made his work recognizable as distinctly his own while giving a furnished room an air of originality, in which the individual elements worked together to form a singular creation, in this case one befitting the individual wishes of the intensely original, wholly modern woman who was Alva Vanderbilt.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Nicole Williams and Carola Schueller of the Preservation Society of Newport County for their invaluable feedback on the early drafts of this article. I offer special thanks to Erin Pauwels, Mariola Alvarez, Thérèse Dolan, and Laura Watts for their continued support as I brought the article to completion. And I am profoundly grateful to Isabel Taube, Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, and the anonymous reviewers at Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide for their comments and for recognizing the value of this article.

Notes

All translations, unless otherwise noted, are my own.

[1] Alva Erskine Smith Vanderbilt Belmont was born in Mobile, Alabama, in 1853 and died in Paris, France, in 1933. I will refer to her in this article as Alva Vanderbilt (shortened to Vanderbilt) unless otherwise noted.

[2] Vanderbilt commissioned US architect Richard Morris Hunt to build the beaux-arts-style Marble House project beginning in 1888 through its completion in 1892. Classically styled after the Athenian Parthenon, it included references to the neoclassical Petit Trianon (1762–68) at Versailles by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, which was designed for Louis XV’s maîtresse en titre (mistress in name), the Marquise de Pompadour, but not completed until after her death.

[3] For French Revival styles in the United States during the late nineteenth century and the courtly mode of furniture and interiors, see Kenneth Ames, Death in the Dining Room and Other Tales of Victorian Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992), 236–37, 190–91. On revivalist, Gilded Age architecture and interiors, see Wayne Craven, Gilded Mansions (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009).

[4] Jules Célestin Allard, who was a cabinetmaker, sculptor, and interior designer, first worked with Vanderbilt on her mansion Petit Château at 660 Fifth Avenue in New York (1882) and then on Marble House (1888–92).

[5] The finely carved wood, painted light gray, recalls the expert cabinet makers of eighteenth-century France, and the lightened palette of Regency Paris and rococo style stands in contrast to the dark colors and heavy, baroque ornamentation at the court of Louis XIV at Versailles.

[6] For the print of 1702 by Daniel Marot, see Cabelle Ahn, “A Bed for a King,” Department of Drawings, Prints and Graphic Design at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, October 9, 2014, https://www.cooperhewitt.org/2014/10/09/a-bed-for-a-king/.

[7] See Henry Havard, Dictionnaire de l’ameublement et de la décoration depuis le XIIIe siècle jusqu’à nos jour, vol. 3 (Paris: Maison Quantin, 1894), 356.

[8] Books in the collection of Allard at the time of his death are listed in Allard & Company Sale by Fifth Avenue Art Galleries (New York, N. Y.), January 11, 1907–January 12, 1907 (New York, 1907). Allard cites Havard’s Dictionnaire in a letter to Cornelius Vanderbilt II: “4 light chairs, design taken from Havard Dictionnaire,” in “Corrected Estimate for the Furniture of the Morning Room at the Residence of Cornelius Vanderbilt, Esq.,” The Breakers, Newport, Rhode Island, February 1, 1895, folder 5, box 41, vault A, The Breakers, Newport Historical Society, Newport, RI (hereafter cited as The Breakers NHS).

[9] On Jules Allard, see Paul F. Miller, “‘Handelar’s Black Choir’ from Chateau to Mansion,” Metropolitan Museum Journal, no. 44 (2009): 199–210; and Paul F. Miller, “Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, arbiter elegantiarum, and Her Gothic Salon at Newport, Rhode Island,” Journal of the History of Collections 27, no. 3 (2015): 347–62. Other discussions of Allard include Charlotte Vignon, Duveen Brothers and the Market for Decorative Arts, 1880–1940 (New York: Giles, 2019); and Richard Guy Wilson, Harbor Hill: Portrait of a House (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008). On the Parisian furniture market, see Christopher Payne, Paris Furniture: The Luxury Market of the 19th Century (New York: ACC Art Books, 2018); Camille Mestdagh and Pierre Lécoules, L’Ameublement d’art français: 1850–1900 (Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 2010); and Denise Ledoux-Lebard, Les Ébenistes du XIXe siècle 1795–1889: Leurs oeuvres et leurs marques (Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 1984).

[10] Allard set up in New York City with Eugène Prignot at 436 Fifth Avenue and in London at 9 Buckingham Street. See Payne, Paris Furniture, 242–43.

[11] For Célestin Allard, see Ledoux-Lebard, Les Ébenistes, 26–28; and Payne, Paris Furniture, 242–43.

[12] Regarding Allard’s “Louis Room” commissions, see Paul F. Miller, “The Truth Improved: A ca. 1903 French Salon at Boston” (unpublished manuscript, 1995); Miller, “Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, arbiter elegantiarum,” 355; Craven, Gilded Mansions, 119; and Bruno Pons, French Period Rooms, 1650–1800: Rebuilt in England, France, and the Americas (Paris: Éditions Faton, 1995). See also Courtney Harris, “Patrons, Period Rooms, and the Museum: The French Salon at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,” Furniture History, no. 57 (2021): 219–34; and John Harris, Moving Rooms: The Trade in Architectural Salvage (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007).

[13] See “After the celebrated Nattier portrait at Versailles,” in Allard & Company Sale, auction cat. (New York: Fifth Avenue Galleries, 1907). For examples of fine and decorative arts exhibited by Allard in his lifetime, see Très riche mobilier, marbres importants, objets d’art, tableaux, sortant des atelier de M. J. Allard, auction cat. (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, December 13–16, 1880), n.p., item 369.

[14] Jules Allard to Cornelius Vanderbilt II, December 14, 1894, folder 5, box 41, vault A, The Breakers NHS.

[15] Jules Allard to Cornelius Vanderbilt II, December 14, 1894, folder 5, box 41, vault A, The Breakers NHS.

[16] The Preservation Society of Newport County holds the largest collection of pieces by Jules Allard et Fils, with well over two hundred individual pieces at Marble House (1892), The Breakers (1895), The Elms (1901), and Rosecliff (1902).

[17] See Katherine Garrett-Cox and Carola Schueller, “Gilded Age Interiors at the Preservation Society of Newport County” in Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Symposium on Wood and Furniture Conservation: Louis, Louis, Louis! Origins, Flourishing and Spread of an International Furniture Style, March 25–26, 2022, ed. Helbertijn Krudop, Tirza Mol, and Paul van Duin (Amsterdam: Stichting Ebenist, 2023), 99–114. Garrett-Cox and Schueller’s article covers survey work conducted by Schueller between December 2021 and April 2022. Schueller reviewed all findings by the author referenced here and consulted on the technical points of this article.

[18] Vanderbilt-Balsan also confirmed this later in correspondence. Consuelo Vanderbilt-Balsan to the Preservation Society of Newport County, October 2, 1964, Marble House digital file, Preservation Society of Newport County Archives, Newport, RI.

[19] For the boudoir “craze” driven by Pompadour, see Joan DeJean, The Age of Comfort: When Paris Discovered Casual—and the Modern Home Began (New York: Bloomsbury, 2009), 178–85.

[20] For nineteenth-century interpretations of Pompadour, see Yuriko Jackall, “American Visions of Eighteenth-Century France,” in Yuriko Jackall and Joseph Baillio, America Collects Eighteenth-Century French Painting, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2017), 7–28. For a discussion of Pompadour’s self-fashioning in the context of the eighteenth century, see Melissa Hyde, Making up the Rococo: François Boucher and His Critics, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2006), 112; and Katie Scott, “Framing Ambition: The Interior Politics of Mme. de Pompadour,” Art History 28, no. 2 (2005): 248–90. See also Xavier Salmon, Madame de Pompadour et les arts, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2002).

[21] On the Goncourt brothers and Pompadour, see Jennifer Forrest, “Nineteenth-Century Nostalgia for Eighteenth-Century Wit, Style, and Aesthetic Disengagement: The Goncourt Brothers’ Histories of Eighteenth-Century Art and Women,” Nineteenth-Century French Studies 34, nos. 1–2 (2005): 44–62.

[22] The Library of Congress contains numerous sketches of Marble House by Hunt that include floor plans and exterior and interior drawings, as well as cross sections of the building at multiple stages, from conception to implementation.

[23] Jeff Moore, former chief conservator at the Preservation Society of Newport County, has pointed out that one of the two windows in the now trophy room matches the hardware of Vanderbilt-Balsan’s bedroom but the other has unique hardware that does not coordinate with Vanderbilt-Balsan’s or Vanderbilt’s windows, suggesting it was its own space with a functional chimney, likely the boudoir/sitting room with a pair of double doors connecting to the adjoining wall of Vanderbilt’s bedroom.

[24] DeJean, Age of Comfort, 178. See also Michel Delon, The Invention of the Boudoir (Paris: Zulma, 1999), 31.

[25] Alva Belmont and Sarah Bard Field, “Memoirs of Mrs. Oliver H. P. Belmont,” 1917, p. 44, box 101, folder 1, C. E. S. Wood Papers, 1829–1980, Huntington Library, San Marino, CA.

[26] See, for example, Michael C. Kathrens, Newport Villas: The Revival Styles 1885 to 1935 (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009).

[27] Hunt’s drawing is labeled in French côté face à la (side facing the) where the corner of the paper is torn away. We can reconstruct this phrase as côté face à la [rue] or “wall facing the street.” Known as the first US architect to train at the École des Beaux-Arts, Hunt was reported to have spoken perfect French. He was often mistaken for French, and he continued to write in French upon returning to the United States.

[28] See Melissa Hyde’s interpretation of the La Tour portrait as a performance and a persona in Making up the Rococo, 112. For the most complete resource on La Tour’s pastel portrait, see Neil Jeffares, “La Tour, Mme de Pompadour,” Pastels & Pastellists, April 7, 2022, http://www.pastellists.com/LaTour.htm.

[29] For Hunt’s approach to working on a project reflective of his and the client’s “merging of their interests,” see James Murray Howard, “Richard Morris Hunt: The Development of His Stylistic Attitudes” (PhD diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1982), 126. Paul F. Miller argues for the juxtaposition of Hunt’s academic classicism with what he terms Vanderbilt’s “cultural tourism” in “Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, arbiter elegantiarum,” 348.

[30] Vanderbilt would continue to style her rooms à la Pompadour by purchasing François Boucher’s Venus at Her Toilette in 1885 and placing it in her New York townhouse at 660 Fifth Avenue. The painting was originally hung in Pompadour’s luxe suite of rooms known as bathing apartments at her château at Bellevue, then later at the Hôtel d’Évreux, Paris. She purchased the painting through C. J. Wertheimer (1895) in London, and it remained at 660 Fifth Avenue until the death of W. K. Vanderbilt in 1920, at which time it was gifted to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[31] Gabriella Szalay discusses the experimental use of violet pigments at Sèvres in “Pompadour, Porcelain, and Pink,” in Madame de Pompadour Painted Pink, ed. A. Cassandra Albinson, exh. cat. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Art Museums, 2022), 62–73.

[32] The fugitive mauve textiles faded to gold and remained as such until 1990, when a reproduction of the textiles was made possible through discovery of original records at Prelle & Cie of Lyon, France, Allard’s frequent collaborator in room textiles. See the unnumbered folder “Mrs. Vanderbilt’s Bedroom,” Marble House, House Files, Preservation Society of Newport County Archives, Newport, RI.

[33] On the color purple in France, where “mauve became the color of high fashion,” see Phillip Ball, Bright Earth: Art and the Invention of Color (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002). On the development of mauve in the 1850s, see Anthony Travis, The Rainbow Makers: The Origins of the Synthetic Dyestuffs Industry in Western Europe (Bethlehem, PA: Lehigh University Press, 1993), 31–64. Travis describes a delegation of France’s Lyon dyers who traveled to London in search of rights to Perkin’s patent but without success. It was not until April of 1858, when Perkin attempted to patent his purple dye in France and failed, that his formula was exposed to the public and began circulating widely.

[34] See Travis, Rainbow Makers, 49–50; and Charlotte Ribeyrol, “John Singer Sargent and the Fin de Siècle Culture of Mauve,” Visual Culture in Britain 19, no. 1 (2018): 6–26. On the Mauve Decade, also known as the Gay Nineties in the United States, see Thomas Beer, The Mauve Decade: American Life at the End of the Nineteenth Century (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1926).

[35] See Horace Mayhew, “Impératrice de la France et de la mode,” Punch, June 18, 1859, 251. The empress appears as a colorful butterfly wearing a hoop skirt to house her crinoline, the invention of which the author gives her credit for, stating: “Again, it is to the same inspiration that the ladies have reason to be grateful for the endowment of that sumptuous and becoming colour, which modistes and Mantallanis delight in calling Mauve.” In Boutibonne and Herring’s Eugénie, Empress of France (1856) the sartorial message is clear: mauve is the fashionable color to wear. Eugénie Bonaparte’s dress, riding coat, and even the decoration on her horse’s bridle bear the color.

[36] Alva Belmont and Matilda R. Young, “Memoir of Alva Murray (Smith) Vanderbilt Belmont,” 1932–33, p. 116, Matilda Young Papers, William Perkins Library, Duke University, Durham, NC.

[37] This portrait was included in the exhibit Versailles Revival 1867–1937. See Laurent Salomé and Claire Bonnotte, eds., Versailles Revival 1867–1937, exh. cat. (Versailles: Château de Versailles, 2020), 316.

[38] See Barbara Dayer Gallati and Ortrud Westheider, High Society: American Portraits of the Gilded Age, exh. cat. (New York: Merrell, 2008).

[39] Portrait of W. K. Vanderbilt II, 1884, exhibited in 1885, now in the Suffolk County Vanderbilt Museum at Eagle’s Nest, the former estate of William K. Vanderbilt II, in Centerpoint, NY. For a reproduction, see Stephanie Gress, Eagle’s Nest: The William K. Vanderbilt II Estate (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2015), 10.

[40] Fernand Cormon, Portrait of Louis-Robert Carrier-Belleuse, 1877, now in the collection of the Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, Paris.

[41] The painting is awaiting XRF (X-ray fluorescence) analysis at the time of this article’s publication.

[42] Numerous articles appeared in early April of 1889, in the New York Times as well as the Buffalo Express.

[43] Allard participated in the Paris World’s Fair of 1867, winning a silver medal, as well as in the Paris World’s Fair of 1887. See Payne, Parisian Furniture, 242.

[44] Émile Bergerat, Les Chefs-d’oeuvres d’art à l’Exposition universelle 1878, vol. 2 (Paris: L. Baschet, 1878), 57–58.

[45] Decorative arts in the 1830s, during the reign of Louis-Philippe, saw a renewed interest in the ordered classicism of the Renaissance, though it was London’s Great Exhibition of 1851 that cemented the success of the Renaissance Revival style. The popularity of the Renaissance Revival idiom in furniture is exemplified by Henri Fourdinois’s Renaissance Revival style cabinet, the grand-prix winner of the Paris World’s Fair of 1867, as well as by Allard’s gold-medal win in 1878 for his own Renaissance cabinet.

[46] For a discussion of Diane de Poitiers as Diana in sculpture and painting, see Kathleen Wellman, Queens and Mistresses of Renaissance France (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 185–223.

[47] “De ses magnifiques ateliers, où l’on compte des légions d’artistes dessinateurs, modeleurs, sculpteurs, il s’est bien gardé d’exclure le simple ouvrier ébéniste, menuisier, tourneur et tapissier; il a introduit, avec un empressement jaloux, les machines-outils les plus perfectionnées; il les a mises en action par une puissante machine à vapeur, reconnaissant que si la main conduite par l’intelligence et le goût peut seule fouiller le bois, le ciseler finement, le faire vivre, aucune main ne saurait, aussi bien qu’une machine, débiter la matière, la raboter, la mortaiser, la tourner et la polir.” “Jules Allard Fils: Ébéniste et sculpteur sur bois,” Le Panthéon de l’industrie: Revue hebdomadaire illustrée des expositions et des concours, January 1, 1879, 369–70.

[48] For example, evidence of Allard’s hands-on approach to working with Cornelius Vanderbilt II and Ogden Goelet can be found in a letter from Allard to Goelet, July 9, 1883, series 3, Interior furnishings and objects, RI, 1882–1897, 15, Collection of Salve Regina University, Newport, RI, https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/goelet-interior/15.

[49] Jules Allard to Ogden Goelet, June 30, 1887, series 3, Interior furnishings and objects, 1882–1897, RI, 23, Collection of Salve Regina University, Newport, RI, https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/goelet-interior/23.

[50] For a discussion of signatures, see Mestdagh and Lécoules, L’Ameublement, 249–55.

[51] While Allard did not stamp the furniture itself, he did stamp some furniture hardware, evidenced at Alice and Cornelius Vanderbilt II’s The Breakers. Additionally, Allard provided a full set of Louis XV brasses for Katherine Mackay’s Harbor Hill mansion on Long Island, presumably stamped by his workshop. Richard Wilson wrote about the brasses as follows: “All the hardware of Louis XV design . . . French make and finished in gild bronze.” Wilson, Harbor Hill, 87.

[52] The survey work, begun in December 2021 by Carola Schueller, comprises a series of assessments of Allard’s furniture in the Newport Mansions. For the purposes of this article, the data will primarily focus on assessments by Schueller and the author completed in 2022–23 in Vanderbilt’s bedroom at Marble House, using some additional examples from other Newport Mansions locations.

[53] Jules Allard to Cornelius Vanderbilt II, December 14, 1894, box 42, folder 5, The Breakers NHS.

[54] See François Lachaud, Le Meuble français à l’Exposition universelle de 1878: Demandes d’admission et questionnaires remplis par les exposants dans la classe 17: Meubles de luxe et à bon marché (Paris: Librairie Le Puits aux Livres, 2014), 180–90.

[55] For Allard’s submission form, see Lachaud, Le Meuble français, 39.

[56] Lachaud, Le Meuble français, 89.

[57] See Garrett-Cox and Schueller’s report on Vanderbilt’s bedroom in “Gilded Age Interiors,” where they indicate the possible use of a steam-powered saw and other mechanical tools. Garrett-Cox and Schueller, “Gilded Age Interiors,” 8.

[58] The terms “old gold” and “old silver” are listed in correspondence between Allard & Sons and Cornelius Vanderbilt II. See Allard & Sons to Cornelius Vanderbilt II, February 1, 1895, “Corrected Estimate for the Furniture of the Morning Room for the Residence of Cornelius Vanderbilt, Esq. ‘The Breakers,’ Newport R.I.,” folder 5, box 41, vault A, The Breakers NHS. Based on my consultations with gilding specialists, the term “old gold” likely refers to the tonality of the gold, possibly the carat of the gold leaf and/or additional pigmented glazes and toning layers.

[59] See Allard & Company Sale. The range of design sources used by Allard is not limited to the titles in his library at the time of his death; however, they indicate that he was aware of contemporary trends issued in the latest design books. His books also point to his interest in French and British heritage sites from before 1800.

[60] Jules Allard Fils, “Statement from Jules Allard to Ogden Goelet,” 1887, series 3, Interior furnishings and objects, Rhode Island, 1882–1897, 22, Collection Salve Regina University, Newport, RI, https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/goelet-interior/22.

[61] Belmont and Field, “Memoirs,” 34.

[62] See Oliver Wunsch, “Making up Race: Whiteness, Pinkness, and Pompadour” in Albinson, Madame de Pompadour Painted Pink, 74–85.

[63] Belmont and Field, “Memoirs,” 75–76.

[64] Belmont and Field, “Memoirs,” 68–72.

[65] Walter Benjamin, “Paris: Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” Perspecta, no. 12 (1969): 163–72.

[66] See Toshio Kusamitsu, “Great Exhibitions before 1851,” in History Workshop, no. 9 (Spring 1980): 9, cited in Bill Lancaster, The Department Store: A Social History (London: Leicester University Press, 1995), 16.

[67] Anca I. Lasc, Interior Decorating in Nineteenth-Century France: The Visual Culture of a New Profession (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2018), 107.

[68] Georges Rémon, Intérieurs d’appartements modernes (Dourdan: E. Thézard Fils, ca. 1892). This book was owned by Jules Allard and appeared in the Allard & Company Sale of 1907.

[69] See William Leach, Land of Desire (New York: Vintage, 1993), 15.

[70] In her memoir of 1917, Vanderbilt remembers her arrival in New York City at the age of seven, though the manuscript shows a line drawn through this portion of the text. Belmont and Field, “Memoirs,” 6. In her later memoir of 1932–33, she confirms the family moved to the city when she was six years old. Belmont and Young, “Memoirs,” 19.

[71] For a history of the Bon Marché, see Michael B. Miller, The Bon Marché: Bourgeois Culture and the Department Store, 1869–1920 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981).

[72] Belmont and Young, “Memoir,” 23–24.

[73] Belmont and Young, “Memoir,” 23.

[74] Stewart was born in Ulster, Ireland, and first came to New York in 1818. He was a New York celebrity, deemed the richest man in Manhattan by 1863. His success was both revered and reviled by the public. His lace insertions and scallop trimmings led to the founding of his first dry-goods operation at 280 Broadway. See City of New York, Landmarks Preservation Commission, “Designation Report for the Sun Building, 280 Broadway in Manhattan,” Designation List 186 LP-1439; and Kirstin Purtich, “Palaces of Consumption: A. T. Stewart and the Dry Goods Emporium,” Visualizing 19th-Century New York, Bard Graduate Center, New York, 2014, https://visualizingnyc.org/essays/palaces-of-consumption-a-t-stewart-and-the-dry-goods-emporium/.

[75] Vanderbilt purchased the Fern Cliff property, located on the east side of Bellevue Avenue, from Francis M. Stout in 1888. See the account of Fern Cliff in George C. Mason, Newport and Its Cottages (Boston: J. R. Osgood, 1875).

[76] Earlier in February the Newport Mercury commented that “the greatest secrecy in all the operations have been observed,” including discouraging contact between workers from one room to the next in Marble House. “Marble House,” Newport Mercury, February 27, 1892, 8.

[77] “The Marble Cottage: First Published Description of Mr. Vanderbilt’s Villa; A Masterpiece of Construction and Decoration by Some of the Greatest Artists,” Observer (Newport, RI), May 9, 1892, 1, 5.

[78] “The Marble Cottage,” 1.

[79] See the unpublished biography of Richard Morris Hunt, written by his widow, Catherine Clinton Howland Hunt, 1895–1909, vol. 3, 338, American Institute of Architects/American Architectural Foundation Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, cited in Paul F. Miller, “A Labor in Art’s Field: Alva Vanderbilt Belmont’s Gothic Room at Newport,” in Virginia Brilliant, Paul F. Miller, and Françoise Barbe, Gothic Art in the Gilded Age: Medieval and Renaissance Treasures in the Gavet-Vanderbilt-Ringling Collection (Sarasota, FL: John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, 2009), 24; and also cited in Alan Burnham, “The New York Architecture of Richard Morris Hunt,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 11, no. 2 (May 1952): 9–14.