The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Emma Conant Church (1831–93) was an American artist who had a successful career painting both original works of art and Old Master copies in the United States and Europe. Regular and affordable transatlantic ships and expanding railroad lines brought significant numbers of Americans to and around Europe for travel and study by the mid-nineteenth century.[1] Many of the travelers wanted souvenirs of their trips, and before originals and photographs were widely available and affordable, those souvenirs frequently consisted of full-size or scaled-down casts and Old Master copies.[2] Yet copies, and the copyists who painted them, occupied a rapidly changing cultural position. Many of the most popular and recognizable paintings represented Catholic subjects, and this created an obvious tension for Protestant Americans.[3] Copyists themselves, many of whom were Americans who went to Europe to study, were described as "mere operatives who infest the galleries of Europe," crowding out art lovers and hiding celebrated paintings behind their easels.[4] But the acquisition of painted copies cultivated an appreciation of the past and the cachet of elite culture in their purchasers. And they had a pedagogical purpose; when copies were brought back to America, where few public collections existed, they became teaching tools for budding artists to emulate. So demand was high, and women, whose natural abilities were thought to be more suited to painting inexpensive copies rather than costly and intellectually demanding originals, responded to that demand, although the necessarily public process of copying a painting was contrary to the norms of female invisibility. This article uses the life and art of Emma Conant Church as a case study of an American woman copyist abroad and the community within which she circulated and succeeded.

Parents of young women artists were cautioned not to send their daughters to Europe unchaperoned, despite—or perhaps because of—the well-known model of Nathaniel Hawthorne's copyist Hilda, a character in his novel The Marble Faun (1860) which was set in the Rome he knew in the late 1850s.[5] But Church was thirty years old when she traveled to Europe, no longer an impressionable girl and already a professional artist. Her decision to work in Italy was probably prompted by knowledge that travel abroad let women push against the social and cultural limits imposed on them in pre-Civil War America; it legitimized them as artists and enhanced their future careers.[6] Like other aspiring women, Church would have been informed by texts like Hawthorne's Marble Faun, Germaine de Staël's Corinne (1807), and Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Aurora Leigh (1857), all of which celebrated Italy as a destination for creative women. In 1864 British author Francis Power Cobbe described Italy as full of women "admirably working their way: some as writers, some as artists of one kind or another, bright, happy, free, and respected by all."[7] And the character of Amy in Louisa May Alcott's Little Women (1868), a thinly veiled version of Alcott's painter sister May, stated that she always wanted to "go to Rome, and do fine pictures, and be the best artist in the whole world."[8] May Alcott was born in 1840, and in many ways her success as an artist abroad was made possible by women like Church who went before her.

Emma Church was the second of the Baptist minister Pharcellus Church and Chara Emily Conant's seven children. The Reverend Church was a religious reformer, a prominent author of theological tracts, and a higher education advocate; work-related moves took the family to Rhode Island, Louisiana, New York, Massachusetts, and Vermont during Church's childhood and early adult life.[9] It may have been his reformist outlook that gave Church, like other women who grew up in similar environments, the freedom to live in Europe while establishing herself as an artist.[10] Church's career spans the era of increased emancipation for women and the growth of the suffragist movement, and her independent behavior puts her at the forefront of these ideas; she was one of very few professional women artists working before the Civil War.

Despite their small numbers, women artists had training opportunities in and around Boston, Chicago, and Brooklyn, where Church lived during her late teens and twenties, as well as various drawing and painting manuals to aid their efforts.[11] However Church studied, an 1860 newspaper article described her as "a very literal and faithful young artist."[12] Her earliest known painting, a still life of grapes, is dated to this year (fig. 1). The close observation of the living plant, in a trompe l'oeil tradition that went back to Pliny's Natural History (35.36), accords with the advice of John Ruskin, whose writings were very popular with American artists at that time.[13] But her adherence to observation—the same skill would serve her well as a copyist and costume painter in Rome—also relegated her work to a lowly position in an established artistic hierarchy that celebrated imagination.[14] Nonetheless, Church had an impressive six paintings accepted for the 1861 National Academy of Design exhibition in New York: a trout, a spaniel, three still lifes of fruit, and one, presumably a genre painting, entitled The Little Stroller's Dream.[15] This was a large number for a woman painter, though all were in the lesser genres, and all were for sale.

But Church did not get to bask in her accomplishment; by the time the exhibition opened she was in Paris. She and her brother William, a correspondent for the New York Sun, sailed on the steamship Arabia on December 12, 1860, docking in Liverpool around Christmas.[16] Following the typical tourist itinerary, they likely went to London where Church could have visited the National Gallery on one of its twice-weekly student days.[17] In 1860, 483 oil painters and 105 watercolorists received permission to copy in the galleries.[18] But Church would have had little time to join them, because the siblings were in Paris by late January; William left soon after to tour the continent, but Church remained to study.[19]

In 1861 Parisian schools did not take female students, so Church may have made private study arrangements. She immediately applied to copy at the Louvre and received her permission card at her residence at 8 Boulevard des Invalides on January 23, allowing her to study in the galleries and, perhaps, to make money by painting copies for travelers.[20] She had to know that copyists led a public life; like the art, they were on view in the galleries and subject to constant scrutiny. Nonetheless, many copyists were women and travelers noticed them; in 1855, art historian and collector James Jackson Jarves observed,

The female copyists at the Louvre are a numerous class, with a decidedly artistic air in the negligence of their toilets. They find time both to fulfill their orders, and have an eye to spare to the public, particularly to their male brethren … they have for their home, during most of the week, the comfortable galleries of the finest museum in Europe; inhabiting a palace by day, and sleeping in a garret at night.[21]

Jarves was presumably a reliable judge of paintings.[22] But the appearance of the work produced by such women seemed to matter less to him than the appearance of the women themselves. It was understood that the visibility necessary to acquire artistic skill ran contrary to women's dictated invisibility, and their presence as copyists caused both discomfort and titillation in male viewers. Henry James even equated the visibility of his copyist character Noémie Nioche in The American (1876) with her sexual availability.

Despite this potential risk to their reputations, women copyists were represented at work at the Louvre as early as 1831, in Samuel F. B. Morse's painting of the Salon Carré (fig. 2) and a few decades later in Winslow Homer's wood engraving of the Grande Galerie in 1868 (fig. 3).[23] Church must have carried the same slim, folding easels, sturdy seats, and other tools of the trade used by the women in these representations. Although this was her first documented experience of copying from a collection of original masterworks, it must have made a great impression on her, and she returned to Paris at least twice later in her career.

This stay in Paris was relatively short, since Church was in Rome by the summer of 1862. The city was at a critical juncture; the papal government, assisted by French forces, opposed the rule of Vittorio Emmanuele II, who had just declared himself king of the otherwise unified Italy. But American visitors like Church largely ignored politics and saw Rome as a popular and hospitable destination with much to see, learn, and purchase.[24] Church probably joined up with others traveling south over the Alps and entered the city by coach through the Porta del Popolo, near the heart of the Anglo-American community around the Spanish Steps. Like most Americans, she would have quickly located Piale's and Spithoever's libraries—to purchase books and photographs and read English-language newspapers—as well as the American consulate near the church of Trinità dei Monti and the banks, shops, and restaurants that catered to travelers' needs.

Rome had the added appeal of being relatively inexpensive. Anne Brewster, who supported herself by writing articles for American publications, maintained a large apartment with servants and an active social life for much less than it would have cost her at home.[25] Travelers who learned to adapt economically to Roman life had food sent to their residences from nearby trattorie, bought wine wholesale in large barrels, and hired carriages only for special occasions.[26] They also benefitted from the steady turnover of apartment and studio rentals, the relative merits of which depended as much on their prior occupants as on their respective conditions, locations, and conveniences. The sculptor Anne Whitney's letters home during her extended stays in Italy, which provide a vivid case study of American women abroad, record where artists past and present worked and lived.[27] She herself was delighted to secure the former residences of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning for two of her visits to Rome and Florence.[28] Not that all of these rentals were especially glamorous; the dark hallways of the aged buildings that housed many of them required a plentiful supply of wax-coated wicks called cerini to light one's way and ensure one's safety.[29] The papal daily Giornale di Roma provided a convenient source of international news and local information; foreigners and residents alike inserted advertisements for missing dogs, language instructors, and studio open houses.[30] Regularly updated strangers' lists, which provided interested parties with the names and nationalities of visitors to the city, kept everyone informed of comings and goings and facilitated socializing.[31] However, since the English-speaking community lived in the same area, visited the same sites, and frequented the same businesses, regular chance encounters were inevitable. Guidebooks provided both historical and practical information, helping with arrangements for torchlight visits to the Vatican and the services of doctors, homeopaths, and dentists, as well as voice, harp, and watercolor instructors and even laundresses.[32]

Artists made their own community within this enclave, which during Church's time in Rome was led by William Wetmore Story, whose long residence in the city and lodgings in the Palazzo Barberini gave him considerable clout.[33] Male artists gathered at the Caffè Greco for meals, mail, and socializing, and they drew from life at the English Academy and at other venues run by the French, the Neapolitans, the Florentines, and the Prussians; this academic training was necessary for creating history paintings, the most elite of the genres, but women were not welcome in these formal settings.[34] Women could, however, make arrangements for private instruction, as Harriet Hosmer did with John Gibson and Alcott with Frederic Crowninshield.[35] More informally, they took advantage of the art around them in the cold museums—dubbed "picturesque refrigerators"—and the surrounding countryside.[36] They also obtained permission to draw informally from the casts at the French Academy and they hired models from the locals who loitered around the Spanish Steps.[37] But they also attended informal studios that were open, in a limited fashion, to artists of both genders; Luigi Talarici, a former model known as Gigi, ran the most popular of these during Church's time in Rome, where models posed for both nude and costume sessions every evening.[38] Women were welcome at the costume sessions, and the resulting paintings of models in local dress or historicizing garb, though criticized by some, were in great demand among travelers as souvenirs of the city, at least until photographs of similar subjects were more widely available.[39] These paintings were made on speculation, and they were sold from studios, libraries, print shops, and other places frequented by travelers.[40] Guidebook listings indicate that Church responded to this market for costume paintings, so her presence at Gigi's is almost certain; she must have been like the occasional women who, according to one contemporary, "would come in quietly, make a sketch, and go away unmolested, and almost unnoticed."[41]

The incursion of women artists into places like Gigi's, or, in rare cases, the Caffe Greco, corresponded with their greater visibility in the city, but they were still inevitably characterized in the language of contemporary sensibilities. For example, in 1866 longtime Roman resident Henry Wreford described them as "a fair constellation … of twelve stars of greater or lesser magnitude, who shed their soft and humanising influence on [the visual arts]."[42] The female sculptors in his constellation were especially prominent; sketching and painting, at least on the amateur level, were acceptable occupations for well-bred ladies, but sculpture was a masculine realm, even if these women rarely carved or cast their own work, and its practice led to both gossip and scandal.[43] Henry James infamously called them a "strange sisterhood of American 'lady sculptors' who at one time settled upon the seven hills in a white marmorean flock."[44] He referred in particular to Hosmer, whose unusually independent activities often caused alarm and who, as Elizabeth Barrett Browning noted, "lives here all alone … dines and breakfasts at the caffes precisely as a young man would; works from six o'clock in the morning till night, as a great artist must."[45] Browning admired the ways in which Hosmer and her companions ignored gender boundaries and referred to them as "emancipated," but she was certainly in the minority.[46] But Rome allowed this emancipation if women wanted it. Nathaniel Hawthorne emphasized this through the voice of his fictional sculptor Kenyon in The Marble Faun; Kenyon observed, "Rome is not like one of our New England villages where we need the permission of each individual neighbor for every act we do, every word we utter, and every friend we make or keep."[47] Hawthorne's copyist Hilda, who lived alone and traveled unchaperoned through the city, was surely a composite of the women artists he encountered in Florence and Rome. The same could be said for the flower painter Augusta Blanchard in Henry James's Roderick Hudson (1875). Both Hawthorne and James knew many of the expatriate women artists active in Italian cities, as did their well-traveled readers, and their descriptions were both convincing and evocative.[48] Over the course of her career, Church was in Europe at the same time as the artists May Alcott, Caroline Petrigru Carson, Eliza Greatorex, Harriet Hosmer, Edmonia Lewis, Vinnie Ream, Emma Stebbins, Anne Whitney, and the sisters Mary E. and Abby O. Williams, among others; these women formed their own supportive community, assisting each other with apartments, studios, and patrons when they could.[49]

Church probably followed the routine typical of most foreign residents and travelers, leaving the city only in the hottest months, when most people fled to avoid the allegedly poisonous air.[50] Her mornings might have been spent in her studio or in lessons, while her afternoons were devoted to social calls, gallery visits, or country rides, and her evenings to more calls, or perhaps working in a studio like Gigi's.[51] Business was not conducted on the many feast days that cluttered the calendar; instead, processions and visits to specially lit monuments entertained Romans and visitors alike. The activities of Holy Week, in particular, forced travelers to a standstill, though most probably shared the feelings of young Hartford native Eliza Sheldon Butler, who observed the celebrations with a critical anti-Catholic eye, finding delight only in the brilliantly lit outline of Saint Peter's basilica in the night sky.[52] Despite the almost anthropological interest they stimulated, such celebrations were not always seen in a positive light: in a letter to her sister Anne Whitney ruefully commented, "Today is a festa. Yesterday was a festa. Every other day about is a festa. On a festa you can get nothing done for money + certainly not for any other consideration."[53]

But Church was there to paint, and in this she found much company. Art was in demand, and artists were said to make "pictures by the yard, and statuary by the pound" to meet the continuous need.[54] Popular novels, journals, newspapers, and guidebooks described artists' studios and listed their addresses and visiting hours.[55] The availability of this information made "doing the studios," as the lawyer Howard Payson Arnold described it, a significant part of most Roman tours.[56] Some of the paintings purchased on these tours were small-scale and relatively inexpensive costume paintings, views of the Roman countryside, or commissioned portraits. But a significant quantity were copies of the celebrated Old Masters hanging in Rome's galleries, which required, as copying at the Louvre required, special permits to execute on site.[57] Copies after the popular so-called portrait of Beatrice Cenci in the Palazzo Barberini, for instance, then attributed to Guido Reni and thought to represent the sixteenth-century girl condemned for arranging the murder of her abusive father, were described by one traveler as "the picture of which we so often see copies in American homes."[58] Even more so than Reni, however, the work of Raphael was particularly revered, whether through painted copies or reproductions in illustrated books.[59] Raphael's name was synonymous with the highest ideals: in Alcott's Little Women, the painter Amy was described as "Little Raphael" while Hawthorne's Marble Faun referred to Hilda as "the handmaid of Raphael."[60] But few modern artists achieved Raphael's level; Hawthorne also criticized the mechanical copies produced by Rome's many "Raphaelic machines."[61]

As Hawthorne's comment implies, both professional and amateur copyists were particularly widespread in Rome, to the extent that travelers complained of the many easels that obstructed their views of famous paintings in the galleries.[62] Just like in Paris, the copyists, rather than the art, became the main attraction. The gendered nature of copying made it particular fodder for novels about Roman life published during this period. Nathaniel Hawthorne contrasted the innocent copyist Hilda with the mysterious painter Miriam throughout his Marble Faun.[63] But even Hilda could lead men astray; Hawthorne noted that she stood out "among the wild-bearded young men, the white-haired old ones, and the shabbily dressed, painfully plain women, who make up the throng of copyists," and some besotted men were lured into painting her, rather than the works in front of them.[64] Most of the professional copyists, of course, were men. The 1858 edition of F. S. Bonfigli's Guide to the Studios in Rome included almost 400 listings for the convenience of travelers, encompassing artists, related occupations, and useful establishments like bankers, libraries, and picture galleries. Thirty-four of the artists were copyists, but only four of these were women.[65] The 1860 edition listed more than 400 such individuals and establishments, 38 of them copyists, of whom five were women.[66] But as women journeyed to Europe in increasing numbers, a significant number of amateur women copyists also worked in the various galleries. Both amateur and professional women artists must have been of particular, if somewhat prurient, interest; in no other context would it be appropriate for an otherwise unrelated man to engage a woman in conversation, never mind walk into her quarters to converse and exchange money for goods. This put women artists in a difficult position. For example, the sculptor Louise Lander suffered from scurrilous and probably unfounded gossip in Rome in the late 1850s, which discomfited Nathaniel Hawthorne so much that he publicly distanced himself from her and her work.[67] As women became more professional in their art, and entered the public sphere on a more regular basis, they inevitably jeopardized both their names and their careers.[68]

Yet Emma Church achieved her greatest success as a copyist in Rome. Her family was not sufficiently wealthy to support her extended European stay, so she had to earn her own income.[69] She probably established herself within the Roman community immediately and opened her studio to travelers. Her break came in June 1862, when the Reverend Milo P. Jewett, then President of Matthew Vassar's newly founded but not yet opened Vassar Female College, was in Rome as part of a tour to visit European institutions of higher learning. Vassar was keen to make his College a serious place for women to learn, a desire shaped by his contact with some of the leading educators of his time, including Jewett and Vassar's own niece Lydia Booth, both of whom had founded female seminaries.[70]

Within this context, Jewett's visit to Rome, and his subsequent contact with Emma Church, was fortuitous. It was while he was on this trip that he met Church and commissioned her to execute four copies for the future college gallery; Trustee minutes report that "from the fullest enquiry made upon the spot she seemed to be the most eminent copyist to be found."[71] Church's eminence, however, is questionable at that date. In the 1862 edition of John Murray's Handbook of Rome, with which most travelers to the city would have been familiar, she is not among the seventeen copyists cited.[72] Yet Jewett must have had a reason to believe he could entrust her with his commission. As a Baptist minister himself, he may have known her father; he certainly knew Rochester University president and Vassar trustee Reverend Martin Brewer Anderson, who knew her father, and Benson J. Lossing, another trustee, knew her brother William.[73] It may well have been a personal recommendation from one of these men that secured the commission for Church, and certainly her potential as a role model for Vassar's female students would have been in the background of Jewett's decision, too.

However the commission came about, Matthew Vassar went along with it. In November 1862 he wrote to Church and stated: "Professor Jewett speaks in the highest terms of your genius, personal, spotless and purity of character, and of the many warm friends you have in Rome which gives weight and additional value to your pictures." [74] He left all decisions about the paintings in her hands, although he expressed his hope that she would use good canvas.[75] A consummate businessman, but never confident with his own aesthetic judgment, Vassar wanted to ensure he got a quality product; what he perceived as trivial details, like iconography, were left to others.

Church's reply of January 1, 1863 mentioned those "warm friends." She assured Vassar that she would "make the most of those advisers who are within reach" and went on to describe her New Year's Day dinner with Charlotte Cushman, Harriet Hosmer, and Emma Stebbins.[76] Church must have assumed Vassar would recognize those names, but it is likely the business-minded brewer did not. Cushman, the actress and lecturer, resided largely in Rome from 1852 to 1870 while supporting an expanding group of women.[77] Her best-known protégée was Hosmer, and Stebbins, also a sculptor, became Cushman's lover and biographer; the three lived together at Via Gregoriana 38, in the heart of the Anglo-American community. Cushman's self-sufficiency was a model to the women in her circle, and her regular socials were occasions for artists and clients to meet; if Jewett did not contact Church through church or college connections he may well have done so at Cushman's home.[78]

According to Church, these friends were eager to assist: "they at once set their heads to work to think what they could do to help on the cause, for as Miss Hosmer said, 'it's for the right sex.'"[79] All four were keenly aware of the difficulties facing women in general, and Church praised Vassar for doing his part to alleviate them. She wrote, "You can be sure now Mr. Vassar of having all the women on your side, especially the noble ones who have the advancement and elevation of their sex at heart. For those here, we all mean to do every thing in our power to make the Vassar Female College one of the noblest and most successful institutions in the world."[80] The enthusiasm of these women was not misplaced; Vassar College did indeed become a leading institution in the suffrage movement and one with close ties to leading female thinkers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[81]

Church's first two Vassar copies were of popular Baroque originals, a Madonna by Carlo Dolci in the Galleria Corsini (fig. 4) and an Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Guercino in the Vatican (fig. 5). Since the Dolci is dated 1862, it was likely already completed and part of her studio stock, intended for purchase by a traveling connoisseur, before she set it aside for the Vassar commission. But the Guercino, which is dated 1863, was probably painted, or at least finished, specifically for the College. Both were completed by April 1863, when Martin Brewer Anderson visited Church's studio. Though untrained in art, the Reverend Anderson effusively declared them better than all other copies in Rome.[82] Church displayed the copies in her studio, an apparently common practice that took advantage of the constant flow of tourists to generate interest and sales.[83] Anderson boasted to Vassar's Executive Committee, "The best artists and connoisseurs in Rome have spoken in the highest terms of the copies and their exhibition has secured for Miss Church several orders already and in my judgment will establish Miss Church's reputation as one of the most promising of our young artists."[84]

On April 14, Church wrote to Jewett and described the care she had taken to have carved and gilded frames made at a reasonable price; she promised to finish the third copy, described as a Raphael, in the fall, and the fourth, still unnamed, after that. She also revealed that she was offered $200 for the Dolci by a gentleman named Gray, but that she kept Vassar's price at $150. Church requested that Jewett unpack the paintings immediately and test them in different lights for best effect, and preempted criticism of their different finishes by stating that she followed the style of the originals; ironically, this rather slavish attention to originals probably diminished the reputation of copyists to many of their contemporaries. Church proudly mentioned Anderson's visit; he "carefully studied the originals and compared my copies with them, and seems to be pleased with my work which is a great relief to my mind. He also likes the frames."[85]

The same letter contains Church's evaluation of her status as a painter. She turned down an offer to teach at Vassar College, stating that she needed to remain abroad for several years: "your very kind offer comes rather too early in my career for me. I am just now where it would be a mistake for me to change even for what may seem for the better."[86] The offer itself is curious because at this early point in the college's history, Matthew Vassar believed in the education of women, but not necessarily education by women; the first female faculty member he hired was Maria Mitchell, an astronomer whose international reputation far surpassed that of Church. Mitchell was hired in 1862, and the College opened in 1865, with Mitchell and Professor of Physiology Alida Avery the only two women of the nine original chief faculty members.[87]

Church also sent Jewett a bill for $450 ($250 for the Guercino, $150 for the Dolci, and $50 for the special frames, which still survive), stipulating that the shipping costs would be added later.[88] That bill was not paid promptly; she wrote again to both Jewett and Vassar on April 28, in an irritated tone, revealing that the paintings would not be shipped until she received payment and noting that she had already been inconvenienced because she had "waived in their favor the usual rule of artists, namely to receive half the pay in advance."[89] Vassar replied on May 22, to tell her Jewett had been out of town and his mail had not been opened so they had only just read her letter; he promised $1,200 on the next day's steamer, representing full payment for these paintings and an advance on the last two.[90] This seemed to resolve the problem. Vassar wrote again in July, telling Church that her paintings arrived and his Board was pleased.[91] His letter also reveals that Church had recommended Hosmer to carve Vassar's bust, although he apparently never followed through with a commission.[92] Church was a less successful artist than Hosmer, and she was certainly less well-known, but her efforts to assist her colleague by finding her a lucrative portrait commission indicates their continuing acquaintance; Hosmer later returned the favor by sending Vassar praise for Church's third copy.[93]

This third (and, despite the original commission, final) Vassar painting was a full-size copy of Raphael's Madonna of Foligno from the Vatican (fig. 6). The choice was not surprising given both Raphael's popularity and the fame of this particular painting.[94] In The Marble Faun, for instance, Hilda is chided for not taking care of herself by a friend who worries that he will find her reduced to "a heap of white ashes on the marble floor, just in front of the divine Raphael's picture of the Madonna da Foligno!"[95] But the original is over ten feet high; in the case of large or complex paintings like this one, copyists might focus on a single detail rather than the entire composition. To execute her full copy Church would have needed a ladder, and climbing that ladder would have been difficult in female dress. In such a public locale it is unlikely she emulated Hosmer, who in the privacy of her studio put on what she described as "Zouave costume" to facilitate movements on a high scaffold.[96]

Perhaps because of the difficulties this copy entailed, Church priced it at $1,200. Even considering its size, this was a high price for a copy, and one usually only commanded for major original works by male artists.[97] Church's confidence must have been bolstered by the success of her first two Vassar copies, and she may have been encouraged by well-paid colleagues like Hosmer. But the price, combined with the belief of some at Vassar that Jewett had commissioned Church without adequate consultation, created animosity. The College decided to have Church's first two copies evaluated by art collector and gallery chairman Reverend Elias Lyman Magoon.[98] To quell the dissent, Vassar decided to buy the Raphael himself to donate to the College.[99] But that dissent continued: the Reverend Magoon argued that the College should not acquire copies at all.[100] There is no record of Magoon's evaluation, but Vassar seems to quote it in a letter to Magoon in January 1864; apparently Magoon described Church as "an undistinguished American artist," and said that funds would have been better spent on original works by better artists.[101] By this time both originals and photographs of them were increasingly affordable and popular, so Magoon's critique had some justification. But his comments were particularly uncharitable because he, like so many in Vassar's administration, may have known Church's father; they both attended meetings of the American Baptist Missionary Union and had similar interests in higher education.[102] And his motivations were probably suspect, since later that same year Magoon sold his own art collection to the College for the then vast sum of $20,000; ironically, that collection included an unsigned half-size copy of Sebastiano del Piombo's Visitation from the Louvre, indicating that Magoon's opinion of copies had shifted with time and circumstances.[103]

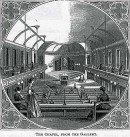

Church was still painting in February 1864, largely unaware of the dissent in Poughkeepsie, when a reporter from the New York Times described her at work, "copying with much success one of [the Vatican's] largest and most valuable pictures."[104] This, of course, must have been the Raphael. From Vassar's correspondence, it seems that both Church and Vassar hoped to exhibit the finished Raphael copy in New York City, an event that would have publicized both the painting and the newly founded College, as well as Church herself.[105] Hosmer may have suggested this course of action since she successfully exhibited several of her own sculptures in this way; indeed, many artists did this with particularly noteworthy works at this time.[106] But the painting took longer to complete, and deliver, than either Church or Vassar anticipated. It was signed 1864 but did not arrive until 1865, and when it did it had water damage from the sea voyage; nevertheless, when the College opened that fall it was displayed in the chapel, set off by red curtains covering the organ (fig. 7).[107] Although the College had no specific religious affiliation, students had mandatory daily prayer in the Chapel, so they were familiar with the space and its furnishings.[108] With such exposure, Church's painting would have served as a constant model for female artists and students. However, typical of nineteenth-century American inclinations, it was acclaimed for its artistic, rather than religious, merits. An 1866 newspaper article even observed that "frequent contemplation of it cannot fail to cultivate the taste of the pupils, and incite in them a desire to know more of the refining influences of art."[109]

Knowledge of Church's three paintings for Vassar Female College must have spread immediately within and beyond the close-knit community of Americans in Rome. It was probably due to this increased notoriety that she was first cited in the 1864 edition of John Murray's Handbook of Rome as a specialist in copies and costumes with a studio at Via di San Nicola da Tolentino 72, in the heart of the artist community, and the following year, as a figure painter, in W. Pembroke Fetridge's Harper's Hand-Book for Travellers in Europe and the East, by which time her studio had moved a few doors down the street to Via di San Nicola da Tolentino 68.[110] These listings, combined with her prominent location, would have brought a steady stream of customers to her door. The same year, her painting of a Roman girl, the property of philanthropist Abiel Abbot Low, was exhibited in the semi-annual exhibition of the Brooklyn Art Association; presumably Low acquired it from her on a trip abroad.[111] In the fall and winter of 1865–66, Church and her Rome studio were mentioned in both The New York Times and Harper's New Monthly Magazine. The brief Times reference described her as a notable landscape and figure painter.[112] She received more extensive treatment in Harper's; her studio was described, in a nod to Hawthorne, as "far up, like Hilda in her tower."[113] At that time Church was working on a copy of a Claude Lorraine landscape in the Louvre for either the financier LeGrand Lockwood or his son of the same name, as well as three costume paintings.[114]

By 1867 Rome was in the throes of revolution, with nationalists pitted against the French-supported papal forces for control of the city. But it was still a destination for American artists and its charms—and deficiencies—were explored in an article in The Galaxy, a journal published by Church's brothers. It is difficult to imagine them publishing such a piece without thinking of their sister, though she was not mentioned in the text.[115] She returned to New York that year, set up a studio in an artists' building at 1227 Broadway, and immersed herself in the community, opening her studio to visitors on Monday afternoons and perhaps even joining the newly-founded Ladies Art Association, a women artists' professional organization.[116] Given her earlier comments to Matthew Vassar about her concerns for "the advancement and elevation" of her gender, it makes sense that Church would seek out such an organization. A newspaper article in March 1867 described her as possessing "unusual talent," and compared her favorably to the better-known artist Eliza Greatorex; the reporter praised Church's skill as a copyist, portraitist, and still life painter and attributed it to her study abroad.[117] Church exhibited two costume paintings in the spring exhibition of the Brooklyn Art Association, and showed two unidentified portraits, a group of ducks, and a costume painting entitled Shepherd of the Apennines at the National Academy of Design.[118] The Academy paintings were singled out for praise in reviews of the exhibition by The New York Times and The Albion.[119]

Despite her success in New York, by late spring of 1868 Church returned again to Europe. This period in her life can only be traced through sporadic newspaper references and guidebook listings. According to these, she was still working in New York in February and March of 1868.[120]However, she must have left by early May because she registered with Parisian bankers later that month.[121] She was described as a figure painter in Rome, again at Via di San Nicola da Tolentino 68, inthe 1868 edition ofHarper's Hand-Book.[122] At some point Church returned to Paris, and remained there during the Prussian siege of 1870–71, when she volunteered for the American ambulance service.[123] After the war she traveled to Antwerp and again to Paris.[124] Later that year Church was in Rome, where she was again listed in two successive editions of Harper's Hand-Book.[125] Church then visited England, apparently for commissions, in early 1872.[126] If these commissions were for National Gallery copies, she was in good company; that year 375 students registered to copy in the museum, the most popular subjects being paintings by Claude-Marie Dubufe and Joshua Reynolds.[127] May Alcott had left London the previous November, after an extended stay copying the paintings of Turner, but Church would have heard of her success from other Americans when she arrived.[128] Conditions were rapidly changing for women copyists at this time; that same year the New York painter Susan Clark Gray noted that in both London and Paris "the most ambitious copyists were women and in many cases pictures of thirty and forty feet were in rapid process of painting and high ladies and scaffolding no barriers to the execution of the work which in many instances was excellent."[129] Apparently these women were not hindered by the sartorial obstacles both Church and Harriet Hosmer faced when working on such a large scale only a few years earlier.

Church seems to have returned, at least briefly, to New York and Chicago in 1874.[130] That October she married businessman James Long and they sailed together for Paris; Long was a widower 26 years her senior and he had been married to her aunt, who died the previous year.[131] The couple must have been well-suited; marrying at 43, after more than a decade living and working abroad, was not something Church would have done lightly. Indeed, prior to this, Church may have agreed with Harriet Hosmer, who stated, "Even if so inclined, an artist has no business to marry…she must either neglect her profession or her family, becoming neither a good wife and mother nor a good artist."[132] This was a common lament, and one that appeared as a plot device in Amelia B. Edwards's novel Barbara's History (1864), where the title character's production as a painter rises and falls with her marriage.[133] It may be no coincidence that we have no evidence for Church's artistic output during the years of her marriage.

Church and Long traveled around Europe until Long's death in Paris in 1876.[134] At this point her biography is even more uncertain. Church may have remained in Paris to study at one of the ateliers then taking female students. She may have continued to paint; a Mrs. Long, with no address provided, exhibited a Study for a Head at New York's National Academy of Design in 1877.[135] A Miss Church was again listed as a figure painter in Rome in the 1878 edition of Harper's Hand-Book; however, these identical references in multiple editions may only indicate that the guidebook was not scrupulously updated.[136] With that final reference, Church seems to disappear from the written record until her death in December 1893 in Port Chester, New York.[137]

Emma Church's independence, as well as her professional success, came during a tumultuous period for travel and art. Americans were going abroad in ever-increasing numbers. At the same time, photographs of European monuments and local color became both widespread and affordable souvenirs for these travelers. One popular souvenir involved inserting specially-purchased photographs into copies of Nathanial Hawthorne's Marble Faun; in 1869 the sculptor Anne Whitney wrote to her sister:

Visitors in Rome this winter find a good deal of amusement in illustrating the Marble Faun with photographs + having the book bound in Roman binding. Who first set this on foot I know not but a good many do it and the time and labor of hunting involved make almost every one who does so heartily sick of it before the end. I have been thinking of doing one for you but concluded that the result wd hardly compensate for the xpenditure + then again as everybody was illustrating the Marble Faun I thought it wd probably be a very old story before it reached you.[138]

And, of course, original works of art (and some fakes, too) were more accessible in the shops of Europe as venerable Italian families sold their patrimony, and this art began to arrive in the growing number of public and private collections in the United States.

As a result of these changes, the formerly vital role of the copyist and costume painter decreased. Like other institutions, Vassar College's pride in and reliance on copies decreased as its collection of originals increased. Despite the early praise it generated, Church's copy of Raphael may have been too problematic for such a prominent position at the College; in 1870, it was moved to the art gallery in Vassar's Avery Hall and Charles Loring Elliot's full-length portrait of Matthew Vassar took its place of honor in the chapel.[139] As archival photographs indicate, all three of Church's paintings were exhibited there, together with other copies and originals and an array of plaster casts of celebrated Ancient and Renaissance sculptures (fig. 8). Yet an 1876 article in Scribner's Monthly described Vassar's teaching collection as inadequate, and noted that the Raphael copy "cost enough to pay for a respectable gallery of large autotypes covering almost the entire range of art history."[140] As this quotation reveals, the unavoidably inexact appearance and high cost of painted copies was deemed increasingly problematic.

Church's greatest success occurred in the 1860s in Rome, where she was part of an important community of women artists who made the city their home and served the tourist population through the production of Old Master copies. But her disappearance from the art world by 1878 may indicate her inability to have adapted to change. It is somewhat ironic that women artists received greater access to formal training and increased professional status at the same time that the reputations of their earlier, pioneering colleagues, like Church, diminished.[141] Nevertheless, the contributions of Emma Conant Church and her contemporaries were critical to the improved status and position of American women artists in the late nineteenth century.

I first examined Church for the exhibition Copies, Casts, and Pedagogy at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, in 2006; my curatorial research was funded by an Andrew W. Mellon Inter-Institutional Faculty Grant and assisted by Margaret E. Dull, Jarrett Gregory, Karen Lucic, Ron Patkus, and Dean Rogers. More recent work was possible due to Wellesley College's Class of 1932 Humanities Research Fund; I am grateful to Temma Balducci, Jane Callahan, Ian Graham, Heather Jensen, Christopher H. Jones, Kathie Manthorne, April Masten, Deborah Pollack, Nancy Siegel, and especially Martha McNamara and Joy Sperling.

[1] This travel generated numerous publications; see Harold F. Smith, American Travelers Abroad: A Bibliography of Accounts Published before 1900 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1969); Mary Suzanne Schriber, Writing Home: American Women Abroad 1830–1920 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997); and William W. Stowe, Going Abroad: European Travel in Nineteenth-Century American Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994).

[2] Since copies could be modified to match contemporary taste, they were often considered better than originals; see Marius Schoonmaker, John Vanderlyn Artist 1775–1852, exh. cat. (Kingston: Senate House Association, 1950), 44; and Mark Twain, Innocents Abroad (Hartford: American Publishing Co., 1869), 191. For the difficult relationship between painting and photography see Angela Miller, "Death and Resurrection in an Artist's Studio," American Art 20, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 84–95.

[3] Jenny Franchot, Roads to Rome: The Antebellum Protestant Encounter with Catholicism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994).

[4] John Waters, "A Word on Original Paintings,"New York Knickerbocker, July 1841, 51.

[5] Elizabeth Dickinson Bianciardi, At Home in Italy (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1884), 20–22.

[6] Mary Cadwalader Jones, European Travel for Women (New York: MacMillan Company, 1900), 3; and Alice A. Bartlett, "Some Pros and Cons of Travel Abroad," Old and New, 1871, 433–42. Women artists in particular depended on texts like Anna Mary Howitt, An Art-Student in Munich (Boston: Ticknor, Reed, and Fields, 1854); and May Alcott Nieriker, Studying Art Abroad and How to Do it Cheaply (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1879).

[7] Francis Power Cobbe, Italics.Brief Notes on Politics, People, and Places in Italy in 1864 (London: Tribner, 1864), 398.

[8] Louisa M. Alcott, Little Women (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1880), 209.

[9] Reverend Church's autobiography, now in the American Baptist Historical Society, makes scant mention of his children. I am grateful to Deborah Bingham Van Broekhoven for assistance with the manuscript, and to Max Roesler, Emma's great-great nephew, for information on the family. See also Frederick Odell Conant, A History and Genealogy of the Conant Family in England and America (Portland: Harris & Williams, 1887), 393–94; John A. Church (Emma's youngest brother), Descendents of Richard Church of Plymouth, Massachusetts (Rutland: Tuttle Company, 1913); and Donald Nevius Bigelow, William Conant Church and the Army and Navy Journal (New York: Columbia University Press, 1952).

[10] Ros Pesman, "In Search of Professional Identity: Adelaide Ironside and Italy," Women's Writing 10, no. 2 (2003): 311. Church's brothers were particularly successful in their respective careers. William Conant and Francis Pharcellus were involved in journalism and literature; they co-edited The Galaxy and William also published The Army and Navy Journal while Francis authored the Sun editorial "Yes Virginia, there is a Santa Claus." Another brother, John Adams, was an internationally-known mining engineer.

[11] Jean Gordon, "Early American Women Artists and the Social Context in Which They Worked," American Quarterly 30, no. 1 (Spring 1978): 54–69; and Nancy Siegel, "Remember the Ladies: Women of the Hudson River School," in Nancy Siegel and Jennifer Krieger, Remember the Ladies, exh. cat. (Catskill: Thomas Cole National Historic Site, 2010), 10–11. Church does not appear in the student records for the National Academy of Design or the Cooper Union in New York; I thank Bruce Weber, Carol Salomon, and David Chenkin for this information. She may have studied with an unidentified artist in Walden, New York, when she used that town as the address for her Crayon subscription; see letters from Church to Crayon editors, February 1855 and December 24, 1855, John Durand Papers, Box 1, New York Public Library (henceforth NYPL).

[12] "Art and Artists," New York Times, November 29, 1860, 3.

[13] John Ruskin, The Works of John Ruskin, ed. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (London: George Allen, 1909), 36:268. My thanks to Rebecca Bedell for this reference.

[14] For further analysis of these differing trends in American art see Patricia Johnston, ed., Seeing High and Low (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

[15] Maria Naylor, The National Academy of Design Exhibition Record 1861–1900 (New York: Kennedy Galleries, 1973), 1:160. Church's paintings attracted no notice but a reference to the many still life paintings on view may have been meant as an insult to the genre; see "Fine Arts.National Academy of Design Concluding Notice," New York Albion, April 20, 1861, 189.

[16] Their passage cost either $60 or $110, depending on class (Boston Daily Advertiser, November 12, 1860, 4); Emma, though not her brother, is listed as a passenger in "Passengers Sailed," New York Commercial Advertiser, December 13, 1860, 3. Numerous accounts attest to the hardship of these voyages; see Harriet Beecher Stowe, Sunny Memories of Foreign Lands (Boston: Phillips, Sampson, 1854), 1:1–13; and Anne Whitney to Sarah Whitney, March 15, 1867, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, Wellesley College Archives (henceforth WCA). For a packing list of items intended in part to deflect these hardships see Louisa M. Alcott, Aunt Jo's Scrap-Bag. Shawl-Straps (Boston: Little, Brown, 1915), 4.

[17] Frances A. Gerard, "Students' Day at the National Gallery," Cassell's Family Magazine, 1893, 119–23.

[18] Annual Report, 1862, National Gallery Archive, London. I am very grateful to Alan Crookham, Archivist at the National Gallery, for his assistance; copyist ledgers for this period are lost.

[19] Bigelow, William Conant Church, 64–76; and William Conant Church, "Letter from Paris," New York Sun, March 11, 1861, 1.

[20]Registres des cartes délivrées aux artistes, permissions délivrées, classement chronologique 1860–1865, LL16, page 23, no. 107, Archives des Musées Nationaux, Paris. My thanks to Alain Prévet, Chargé d'études documentaires principal responsable des archives des musées nationaux, and Touba Ghadessi, Wheaton College, for their generous help with this citation. For Louvre regulations see Boston Art Students' Association, The Art Student in Paris (Boston: T. R. Marvin and Son, 1887), 39–43.

[21] James Jackson Jarves, Parisian Sights and French Principles, Seen Through American Spectacles (New York: Harper and Bros., 1855), 150–51. See also Mrs. Edwards, "Steven Lawrence, Yeoman," Temple Bar, December 1867, 167–68; Nathaniel Hawthorne, The French and Italian Notebooks, ed. Thomas Woodson (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1980), 15; and Lydia Huntley Sigourney, Pleasant Memories of Pleasant Lands (Boston: James Munroe, 1842), 273.

[22] For further information on Jarves see Charles Colbert, "A Critical Medium: James Jackson Jarves's Vision of Art History," American Art 16, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 18–35.

[23] Patricia Johnston, "Samuel F. B. Morse's Gallery of the Louvre," in Johnston, Seeing High, 42–65; and "The Louvre Gallery," Harper's Weekly, January 11, 1868, 25–26. For women copyists at the Louvre see Paul Duro, "The 'Demoiselles a Copier' in the Second Empire," Women's Art Journal 7, no. 1 (1986): 1–7.

[24] For the vast literature on this topic see especially Regina Soria, Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century American Artists in Italy (Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1982); Irma B. Jaffe, ed., The Italian Presence in American Art 1760–1860 (New York: Fordham University Press, 1989); William L. Vance, America's Rome (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989); Theodore E. Stebbins Jr., ed., The Lure of Italy. American Artists and the Italian Experience 1760—1914, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc., 1992); and Paul S. D'Ambrosio, ed., America's Rome: Artists in the Eternal City, 1800–1900, exh. cat. (Utica: Brodock Press, 2009).

[25] Helen Barolini, Their Other Side: Six American Women and the Lure of Italy (New York: Fordham University Press, 2006), xviii. For cost of living calculations see also Regina Soria, Elihu Vedder American Visionary Artist in Rome (Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1970), 255n3; W. L. Alden, "A Day with the Painters," Galaxy,February 1, 1867, 309–15; Alice A. Bartlett, "Our Apartment. A Practical Guide to Those Intending to Spend a Winter in Rome," Old and New, 1871, 399–407 and 663–71; and Dolly Sherwood, Harriet Hosmer, American Sculptor, 1830–1908 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1991), 67. Anne Whitney estimated she would need $2,000 for her year of study in France and Rome in 1868. Anne Whitney to Sarah Whitney, March 6, 1868, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, WCA.

[26] For examples of such behavior, see the letter from Mary Shannon to Sarah Whitney, January 6, 1868, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, WCA, "we have our dinners sent to us daily in a tin-box in which there are coals, and it is served out to us just as hot as thought it came from our own kitchen at 7 francs for all three of us, from which enough remains for our breakfast and lunch, and then we have some to give to a poor old woman."; and Bartlett, "Our Apartment," 663–64 and 666–67.

[27] "We have taken rooms in a house strongly recommended by Miss Foley, on the Pincian (hill), 107 via Filice—Primo Piano- that is the first floor—what we call the 2nd floor at home—the ground floor counting for no floor at all…It is a good place to be in for a little while but when there are more apartments to let we can find a more open space for less price. Flaxman lived + worked here in a little studio upstairs not far from this is a house in wh Salvator Rosa lived + another the home of Claude Lorraine." Anne Whitney to Sarah Whitney, May 2, 1867, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, WCA.

[28] Apparently the Brownings left a great impression on their Roman landlady, even a decade after Elizabeth's death; Whitney tells her sister, "The Brownings were here for some years + our padrona gave us yesterday some little pleasant anecdotes of them. She seems to have been very fond of them + when we asked her if she remembered a husband + wife + little boy, English, who were here so many years ago she said "O yes una signora Poetessa (that's Mrs Browning) tanta buona tanta buona" so good so good." Anne Whitney to Sarah Whitney, January 14, 1871, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, WCA. Whitney rented the Browning's former Florentine residence, Casa Guidi, when she traveled to Florence alone in early 1876; she instructed her partner Adeline Manning, "Casa Guidi is enough [of an address] on the letters – 2o po." Anne Whitney to Adeline Manning, February 27, 1876, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, WCA.

[29] Alden, "A Day with the Painters," 309; and Henry P. Leland, Americans in Rome (New York: Charles T. Evans, 1863), 128.

[30] For examples, see the various notices in Giornale di Roma, March 12, 1861, March 10, 1862, and January 30, 1862.

[31] I have not found any examples of actual strangers' lists from this period in Rome in my research. However, the importance of these lists in the daily lives of many travelers and artists is evident from references in a variety of diaries and letters; for example, upon her arrival in Rome in 1868 Anne Whitney wrote, "We walked out with the intention of going to Hattie's studio but were overtaken by a shower and were obliged to turn back. Unfortunately that evg our names appeared in the Strangers' List. So Friday morning before we were up, a note came from Hattie, inquiring "She had seen Aunt Mary's name in the List. Was it her Aunt Mary? If so, would she see her in the evg? + if so, would she + her flock come and dine with her on Saturday?" Anne Whitney to Sarah Whitney, January 6, 1868, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, WCA.

[32] For examples of this kind of information, see the unpaginated section labeled "First-Rate Establishments of the Fine Arts and Other Trades" at the back of F. S. Bonfigli, Guide to the Studios in Rome with Much Supplementary Information (Rome: Tipografia Legale, 1860).

[33] On Story and his long residence in Rome see his Roba di Roma (London: Chapman and Hall, 1863); and James, William Wetmore Story.

[34] For the male artist's life in Rome, see James E. Freeman, Gatherings from an Artist's Portfolio (New York: D. Appleton, 1877), 10–16; George L. Brown, "Artist Life in Rome. The Caffe Greco Again," Zion's Herald, May 28, 1868, 254; and Mary K. McGuigan, "This Market of Physiognomy: American Artists and Rome's Art Academies, Life Schools, and Models, 1825–1870," in D'Ambrosio, America's Rome, 39–71.

[35] For early sources on the careers of Hosmer and Alcott, see Cornelia Carr, ed., Harriet Hosmer: Letters and Memories (New York: Moffat, Yard, 1912) and Caroline Ticknor, May Alcott: A Memoir (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1928).

[36] Alcott, Aunt Jo's Scrap-Bag, 166; and William H. and Jane H. Pease, ed., The Roman Years of a South Carolina Artist: Caroline Carson's Letters Home, 1872–1892 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2003), 47.

[37] On the use of casts at the French Academy, see Anne Whitney to Sarah Whitney, October 17, 1868, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, WCA, "Just round that balustrade to the left of the picture is the French Academy, the old Medicean villa with beautiful grounds + fountains + there are rooms filled with casts from all the best antiques + we have permits to go there + study or work all day long if we chose. I have been there nearly all day." On the use of models, see F. W., "Notes in Rome, Artistic and Social," London Society, April 1866, 320–24; McGuigan, "This Market," 63–68; and Ticknor, May Alcott, 107–8. In 1867 Anne Whitney reveled in the many resources, including models, available in Rome: "Living models I must use unsparingly + the vast difference between working here + at home is at once manifest in the abundance with wh these necessities of study present themselves to you without any wearisome search. The moment yr wants are known an hundred offers are at yr service." Anne Whitney to Sarah Whitney, November 17, 1867, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, WCA.

[38] "A Journey from Westminster Abbey to St. Peter's," Bentley's Miscellany, 34 (1853), 506–18; Leland, Americans in Rome, 105–7; and McGuigan, "This Market," 58–62.

[39] William James Stillman, The Old Rome and the New and Other Studies (London: Grant Richards, 1898), 205; and Simonetta Tozzi, "Tra pittura e fotografia: costume, ritratti e reportages di guerra," in Pittori fotografi a Roma 1845–1870, ed. Lucia Cavazzi, exh. cat. (Rome: Multigrafia Editrice, 1989), 91–125.

[40] Leland, Americans in Rome, 148.

[41] Ibid., 106. See also Margaret Bertha Wright, "'Gigi's:' A Cosmopolitan Art-School," Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, January 1881, 9–16; and Ellen Creathorne Clayton, English Female Artists (London: Tinsley Brothers, 1876), 2:160–61.

[42] H[enry].W[reford]., "Lady-Artists in Rome," Art-Journal, n.s., 5 (June 1866): 177.

[43] On these sculptors, see Joy S. Kasson, Marble Queens and Captives: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990).

[44] Henry James, William Wetmore Story and his Friends, from Letters, Diaries, and Recollections (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1904), 1:257.

[45] Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Letters to her Sisters 1846–1859, ed. Leonard Hutley (London: John Murray, 1932), 196.

[46] Ibid. For criticism of Hosmer see James, William Wetmore Story, 1:254–59; and Elihu Vedder, The Digressions of V (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1910), 334.

[47] Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, or, The Romance of Monte Beni (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1901), 124.

[48] On the lives of Hawthorne and James in Italy, and their interactions with both artists and travelers, see in particular Hawthorne, French and Italian Notebooks; and Henry James, Italian Hours (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1909).

[49] See, for example, Anne Whitney's account of her attempts to assist the painter Anna Blunden: "One evng this week we had neighbors Cushman + Stebbins to tea along with Miss Blunden an English watercolor artist of unusual ability. She spent another evening with us a little while before + gave us an acct of her struggles + the absolute want of recognition in her art in a practical way with wh she had to contend in England, notwithstanding that Ruskin + Holman Hunt + others had given her the highest praise. She told us that a picture by a well known watercolorist on xhibition at the same time with one of hers but adjudged inferior sold for 400 pounds while hers bought but 40 + this difference in success she attributed to the superior opportunities wh a male artist has of going about + making himself known among editors + newspaper puffers. She spoke with a good deal of self appreciation but not like a deluded or conceited person + her pictures wh we went to see fully bear out her opinion being very delicate and faithful studies. So we promised to speak of her + send people as far as we were able to her room wh is on the 4th story of a pension + not in the way of the world." Anne Whitney to Sarah Whitney, February 7, 1869, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, WCA.

[50] This dangerous air was so well known it became a plot element in Henry James's Daisy Miller (1878).

[51] Anne Whitney commented on the constant social obligations in 1868: "The bane of students + students' work here is this eternal going. The now acknowledged best painter in Rome Hotchkiss has kept himself entirely aloof from it + his work thanks him + the public thanks it…He paints + lives in one of those altitudinous lofts in Roman houses that are reached by toil of heart +breath + foot but delightful when once attained." Anne Whitney to Sarah Whitney, December 25, 1868, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, WCA.

[52] Butler observed, "Easter our 2nd from home, we could not think it right to spend it at St Peter's, witnessing all these foolish ceremonies, so we merely went for a few minutes to see the procession pass us…in the evening to see the illumination of St Peter's, we took our place in the square, where we waited a long time & saw them gradually light it up, the men were all over the dome, we could see them hanging there, at just eight they lighted all the pans of shavings at once, the effect was indescribably beautiful, the whole church was a mass of light, I do not think it could be imagined." Journal of Eliza Sheldon Butler, April 4, 1858, Butler McCook House, Hartford, Connecticut.

[53] Anne Whitney to Sarah Whitney, June 23, 1867, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, WCA.

[54] Freeman, Gatherings, 35; see also William Cullen Bryant, Letters of a Traveler (New York: D. Appleton, 1859), 259; and Leland, Americans in Rome, 164–72.

[55] See, for example, P. H. Fitzgerald, Roman Candles (London: Chapman and Hall, 1861), 190–96; and S. W., "A Glance at Rome in 1862," Bentley's Miscellany, 51 (January 1862), 640–45.

[56] Howard Payson Arnold, European Mosaic (Boston: Little, Brown, 1864), 259.

[57] Rembrandt Peale, Notes on Italy Written During a Tour in the Years 1829 and 1830 (Philadelphia: Carey and Lea, 1831), 132.

[58] Lucy Yeend Culler, Europe, Through a Woman's Eye (Philadelphia: Lutheran Publication Society, 1883), 89. For a copyist claiming to have made some five hundred copies of this painting see Charles Richard Weld, Last Winter in Rome (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green, 1865), 383.

[59] James P. Walker, Book of Raphael's Madonnas (New York: Leavitt and Allen, 1860).

[60] Alcott, Little Women, 63; and Hawthorne, Marble Faun, 71.

[61] Hawthorne, French and Italian, 315. For Raphael's popularity, see David Brown, Raphael and America (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1983), 15–96.

[62] Benjamin Silliman, A Visit to Europe in 1851 (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1853), 105; Charlotte A. Eaton, Rome in the Nineteenth Century (London: George Bell and Sons, 1892), 2:60–61; and Hippolyte Taine and John Durand, Italy: Rome and Naples, Florence and Venice (New York: Leypoldt and Holt, 1871),141–42.

[63] David Leverenz, "Working Women and Creative Doubles: Getting to The Marble Faun," in Hawthorne and the Real: Bicentennial Essays, ed. Millicent Bell (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2005), 144–58.

[64] Hawthorne, Marble Faun, 72–73.

[65] F. S. Bonfigli, Guide to the Studios in Rome with Much Supplementary Information (Rome: Tipografia Legale, 1858). The figures I provide for both editions were culled from information scattered throughout the volumes.

[66] Bonfigli, Guide to the Studios in Rome (1860).

[67] Charmaine Nelson, The Color of Stone: Sculpting the Black Female Subject in Nineteenth-Century America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 34–35.

[68] Laura R. Prieto, At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 70–107.

[69] On Church family finances see Bigelow, William Conant Church, 94–95 and 232. Church was well integrated into European life. For example, she utilized the consular services for various administrative tasks; see Leo Francis Stock, Consular Relations between the United States and the Papal States: Instructions and Dispatches (Washington, DC: American Catholic Historical Association, 1945), 274, 276, and 306. Her correspondence with Vassar and Jewett reveals that she also had accounts with the bankers Freeborn and Co. in Rome and John Monroe and Co. in Paris to deal with financial matters.

[70] On Jewett, Booth, and the beginnings of Vassar College see Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, Alma Mater: Design and Experience in the Women's Colleges from their Nineteenth-Century Beginnings to the 1930s (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1993), 30; William H. Brackney, Congregation and Campus: North American Baptists in Higher Education (Macon: Mercer University Press, 2008); and Renée L. Bergland, Maria Mitchell and the Sexing of Science: An Astronomer among the American Romantics (Boston: Beacon Press, 2008), 166–67.

[71] Trustee Minutes, June 1862, Vassar College Archives and Special Collections Library (henceforth VCASCL).

[72]A Handbook of Rome and its Environs (London: John Murray, 1862),23 and 287.

[73] For the interrelationships between New York state universities and the Baptist community see Jesse Leonardo Rosenberger, Rochester and Colgate: Historical Backgrounds of the Two Universities (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1925).

[74] Matthew Vassar to Emma Conant Church, November 21, 1862, Box 8, Folder 202, 58–59, Matthew Vassar Papers, VCASCL. This letter, like several others, is transcribed in Matthew Vassar, Autobiography and Letters of Matthew Vassar, ed. Elizabeth Hazelton Haight (New York: Oxford University Press, 1916), 107–8; other of Vassar's letters apparently survive only as transcriptions.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Emma Conant Church to Matthew Vassar, January 1, 1863, Archives File 2.7, VCASCL. A festive dinner at the Cushman residence during this period consisted of "American oysters and wild boar with agro-dolce sauce, and dejeuners including an awful refection menacing sudden death, called 'woffles,' eaten with molasses." Cobbe, Italics, 358. Since Church dined there on a holiday, the menu may have been similarly extravagant.

[77] Lisa Merrill, When Romeo was a Woman: Charlotte Cushman and her Circle of Female Spectators (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999); and Sara Foose Parrott, "Networking in Italy: Charlotte Cushman and 'The White Marmorean Flock'," Women's Studies 14, no. 4 (1988): 305–38.

[78] Cushman continued this social whirl throughout her time in Rome; in 1868, according to Anne Whitney, "Miss C has had a pretty severe winter—never she says has there been such a rush + her time is all given to taking strangers in. It is an inconscionable task wh she imposes on herself to see + entertain crowds of people who she doesn't care for + wd never know again." Anne Whitney to Sarah Whitney, April 30, 1868, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, WCA. See also "The Last Winter's Work of our Roman Artists—The Painters," Zion's Herald, 46, September 2, 1869, 410.

[79] Emma Conant Church to Matthew Vassar, January 1, 1863, Archives File 2.7, VCASCL.

[80] Ibid.

[81] For further information on this see the various sources available at http://150.vassar.edu/index.html I am grateful to Colton Johnson and Susan Kuretsky for their assistance with my queries about the College's role in women's history.

[82] Martin Brewer Anderson to Matthew Vassar, April 8, 1863, Archives File 2.7, VCASCL.

[83] Anne Whitney did the same with some of her sculpture: "This week I shall open my studio in the PM's to those who choose to come but as I give only vive voce invitations to the few I chance to know or whom I meet or who have xpressed a desire to come I shall probably see but a very few." Anne Whitney to Sarah Whitney, March 22, 1868, Anne Whitney Papers, Correspondence, WCA. Other artists were more savvy marketers; for an announcement of Carl Bloch's studio exhibition of his painting Prometheus Unbound, see "Belle arti," Giornale di Roma, February 3, 1865, 108. Coincidentally, Bloch's studio was on the first floor of Via di San Niccolo da Tolentino 72, the same address as Church's studio in 1864.

[84] Martin Brewer Anderson to Matthew Vassar, April 8, 1863, Archives File 2.7, VCASCL.

[85] Emma Conant Church to Milo P. Jewett, April 14, 1863, Archives File 2.7, VCASCL.

[86] Ibid. She suggested Cornelia Conant, a colleague and relative, as an alternative; for information on Conant see Naylor, National Academy, 1:182–83; and Lois Fink, American Art at the Nineteenth-Century Paris Salons (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 331.

[87] Edward R. Linner, Vassar: The Remarkable Growth of a Man and his College 1855–1865,ed. Elizabeth A. Daniels (Poughkeepsie: Vassar College, 1984).

[88] A copy of the bill was included in Emma Conant Church to Milo P. Jewett, April 18, 1863, Archives File 2.7, VCASCL. However, it no longer survives.

[89] Emma Conant Church to Milo P. Jewett and Matthew Vassar, April 28, 1863, Archives File 2.7, VCASCL.

[90] Matthew Vassar to Emma Conant Church, May 22, 1863, Box 8, Folder 202, 66, Matthew Vassar Papers, VCASCL.

[91] Matthew Vassar to Emma Conant Church, July 16, 1863, Box 8, Folder 202, 69–70, Matthew Vassar Papers, VCASCL; and Vassar, Autobiography, 115–16.

[92] Matthew Vassar to Emma Conant Church, July 16, 1863, Box 8, Folder 202, 69, Matthew Vassar Papers, VCASCL; and Vassar, Autobiography, 116.

[93] Vassar, Autobiography, 155–56.

[94] For this painting see Brown, Raphael, 22–23. Rembrandt Peale described the Guercino and the Raphael as two of the best paintings in the Vatican. Peale, Notes on Italy, 132–33.

[95] Hawthorne, Marble Faun, 118.

[96] "To-morrow I mount a Zouave costume, not intending to break my neck upon the scaffolding, by remaining in petticoats," Carr, Harriet Hosmer, 122.

[97] Joy Sperling, ""Art, Cheap and Good:" The Art Union in England and the United States, 1840–60," Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 1, no. 1 (Spring 2002), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring02/qart-cheap-and-goodq-the-art-union-in-england-and-the-united-states-184060 (accessed July 27, 2011). Copies cost between $10 and $60 in the 1850s, indicating that Church's later prices were high; see James Jackson Jarves, Italian Sights and Papal Principles Seen through American Spectacles (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1856), 106. Due in part to the limited opening hours of the various museums and galleries, copies often represented a significant outlay of time; it could take two months to copy a relatively simple composition like Raphael's Madonna della Sedia. "Art," Eclectic Magazine, August 1870, 253.

[98] Linner, Vassar, 155.

[99] Ibid.; and Vassar, Autobiography, 119–20. The College later reimbursed him.

[100] Linner, Vassar, 157. See also Report to Trustees, February 1864, Archives File 1.30, VCASCL.

[101] Linner, Vassar, 157–58.

[102] See, for example, the references to both men in American Baptist Missionary Union, Fortieth Annual Report: With the Proceedings of the Annual Meetings, Held at Philadelphia, May 16-19, 1854 (Boston: Missionary Rooms, 1854).

[103] I am grateful to Joann Potter, Registrar and Collections Manager at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College, for access to object files that provided this information.

[104] "American Art Abroad," New York Times, March 6, 1864.

[105] Vassar, Autobiography, 155.

[106] Hosmer's Zenobia in Chains, for example, was on display at the Derby Gallery in New York from November 1864, and at the Child and Jenks Gallery in Boston from January 1865; see Kate Culkin, Harriet Hosmer: A Cultural Biography (Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2010), 77–78.

[107] Cyrus Swan to Emma Conant Church, March 28, 1865, Archives File 2.7, VCASCL; and Benson J. Lossing, Vassar College and its Founder (New York: C. A. Alvord, 1867), 126–28.

[108] W., "Vassar Female Institute," Advocate and Family Guardian 31, no. 19 (October 6, 1865): 225.

[109] "The Vassar Female College. Its Origin and History. The Course of Study," New York Evening Post, August 8, 1866, 1.

[110]A Handbook of Rome and its Environs (London: John Murray, 1864), xlv; andW. Pembroke Fetridge, Harper's Hand-Book for Travellers in Europe and the East (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1865), 331.

[111] Brooklyn Art Association, Catalogue of Pictures Exhibited at their Fall (Eighth) Exhibition, exh. cat. (Brooklyn: The Union Steam Presses, 1864), no.155.

[112] "American Travelers and American Artists in Europe," New York Times, October 15, 1865.

[113] Katherine G. Walker, "American Studios in Rome and Florence," Harper's New Monthly Magazine, June 1866, 103. Hilda's tower, made famous through Hawthorne's novel, was in fact the Torre della Scimmia, on the corner of Via della Scrofa and Via Portoghesi; see S. Russell Forbes, Rambles in Rome:An Archaeological and Historical Guide to the Museums, Galleries, Villas, Churches, and Antiquities of Rome and the Campagna (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1892), 146–47. This same year Church was also cited as a Roman painter in The American Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events of the Year 1866 (New York: D. Appleton, 1867), 823.

[114] LeGrand Lockwood Senior and Junior traveled to Europe that year; Lockwood Senior's art collection was sold in 1872, but Church's painting was not included (Executrix' sale: The Entire Collection of Important Modern Paintings, Statuary, Bronze, Articles of Vertu, etc; Belonging to the Late Mr. Le Grand Lockwood (New York: George A. Leavitt, 1872). Lockwood Junior's collection cannot be traced.

[115] Alden, "A Day with the Painters," 309–15. They similarly published an account of artists in France; see Albert Rhodes, "Views Abroad: A Day with the French Painters," Galaxy, July 1873, 1–15.

[116] "Art Gossip. The Artists in the University Building – Some of the Lady Artists of New York," New-York Commercial Advertiser, March 21, 1867, 2. I am grateful to April F. Masten for the suggestion that Church joined the Ladies Art Association; its records do not survive intact so I cannot confirm Church's involvement.

[117] Ibid. The author also praises Church's relative Cornelia Conant, whom Church had earlier suggested as a professor for Vassar College; see note 86 above.

[118] Brooklyn Art Association, Catalogue of Pictures Exhibited at their Spring Exhibition at the Academy of Music Brooklyn, exh. cat. (Brooklyn: The Union Steam Presses, 1867), 2; and Naylor, National Academy, 1:160.

[119] "The National Academy of Design," New York Times, April 24, 1867, 4; and "Fine Arts, Exhibition of the National Academy of Design," New York Albion, April 27, 1867, 201.

[120] "The Women Artists of New York and Its Vicinity," New York Evening Post, February 24, 1868, 2; and "Art Gossip, The Lady Artists of Brooklyn and Vicinity," Brooklyn Eagle, March 6, 1868, 2.

[121] "Personal," New York Times, May 29, 1868, 2.

[122] W. Pembroke Fetridge, Harper's Hand-Book for Travellers in Europe and the East (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1868), 387.

[123] "American Artists in Europe," Philadelphia Inquirer,February 3, 1871, 7; I am grateful to Emily Burns for information on the ambulance. Church does not appear in the lists of volunteers provided in Thomas W. Evans, History of the American Ambulance Established in Paris During the Siege of 1870–71 (London: Chiswick Press, 1873).

[124] "Americans Abroad," New York Times, March 20, 1871.

[125] W. Pembroke Fetridge, Harper's Hand-Book for Travellers in Europe and the East (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1871), 448; and W. Pembroke Fetridge, Harper's Hand-Book for Travellers in Europe and the East (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1872), 455.

[126] "Personal," New York Tribune, March 25, 1872, 5.

[127] Annual Report, 1872, National Gallery Archive (London). Again, I am very grateful to Alan Crookham, Archivist at the National Gallery, for assistance.

[128] Ticknor, May Alcott, 99–101.

[129] Susan Clark Gray to Alice Donlevy, March 8, 1872, Box 1, Letters 1870–1879, Alice H. Donlevy Papers, NYPL.

[130] "Fine Arts," New York Times, March 15, 1874.