The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Nineteenth-Century Landscape Photographers in the Americas: Artists, Journeymen or Entrepreneurs?

Snite Museum of Art

The University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana

February 13–March 27, 2011

Nineteenth-Century Landscape Photographers in the Americas: Artists, Journeymen or Entrepreneurs?

Edited by Micheline Nilsen with contributions by Jeff Wimble, Krista Bailey, Stephanie McCune-Bell, Krista Kuskye, Melissa Bebout, Jennifer Wimble, Karla Forsythe, Jonathan Lawson, Joan E. Evens, Ayesha Mowry, Tabetha Coburn-McDonald, Lucas Eggers.

South Bend, Indiana: Wolfson Press, 2011.

Ix+ 97 pp.; 21 b/w illustrations; list of illustrations; notes; bibliography.

$15

ISBN: 9780979953293

Two of Eadweard Muybridge's large plate photographs from Yosemite were easily visible from outside the glass-walled entry to the Sholz Family Works on Paper Gallery (fig. 1). Their vivid presence created a compelling invitation to come in to see more of what was being offered from the collections of the Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame. Step through the door, and immediately to the right, ready for the close viewing it demands, was George Barnard's complex image of Lu-La Lake Atop Lookout Mountain (fig. 2). The exhibition, Nineteenth Century Landscape Photographers in the Americas: Artists, Journeymen or Entrepreneurs? looked at seventeen gems from the history of American landscape photography in an exhibition and catalogue offered to the public by student curators.

It's not unusual for photography to be exhibited at the Snite Museum. While photography is always a crowd pleaser, the museum has strong holdings in photography, which allow for an extraordinary variety of specialized and scholarly exhibits. It's not unusual for one of the special exhibitions drawn from the museum collections to have had student participation in its development. Hands-on education is one of the responsibilities of a college or university museum. Art history faculty and museum staff at Notre Dame, like their counterparts at other institutions, are constantly finding ways for art history students to work with objects and displays in the museum.

However, the creators of this exhibition were not art history students and not even from Notre Dame. For this exhibit, the Snite Museum opened its resources to the students of Micheline Nilsen, Associate Professor of Art History at neighboring Indiana University at South Bend. This was an exemplary cooperation between the institution with the collection and a teacher/scholar from another school who could utilize that collection for her students to develop both research skills and a sense of professionalism. Part of the reason for considering this exhibition is to see how twelve students from a Masters in Liberal Studies seminar developed a small exhibition and its themes. What they discovered as they worked was illustrated not only by what they hung on the walls, but also in the accompanying catalogue that they wrote. Indiana University at South Bend provided support for the catalogue to be published by the Wolfson Press at IUSB.

This is not the first time that Nilsen has cooperated with the Snite Museum. She works with the urban scene of nineteenth-century Europe and is recognized for her book, Railways and the Western European Capitals: Studies of Implantation in London, Paris, Berlin, and Brussels. The Snite Museum, with holdings in photography that include the Janos Scholz Collection of nearly 10,000 nineteenth-century European photographs, was an excellent place for her to exercise her expertise. In 2008 she selected twenty items to show The Architecture of Everyday Places: Nineteenth-Century Photographs of the Vernacular. Her concern for the many ways in which architectural photographs document aspects of history was developed further with a 2010 exhibition, Documenting History, Charting Progress and Exploring the World. Nilsen, with support from both IUSB and Notre Dame, organized an international symposium that brought scholars from as far as Ankara and Madrid for presentations on history and politics as enlightened by the study of historical photographs.

The student-curated show of seventeen photographs that is under consideration here was different in many ways from this prior display of nineteenth-century photographs selected by Nilsen herself. Not fifty-nine photographs, but seventeen. Not displayed in one of the Snite's large spaces for temporary exhibitions, but in its most intimate site. And, in particular, it was not devoted to architecture or to Europe, but to landscape and the Americas. This was an initial limitation set by the professor.

Next, a seminar of twelve students with little or no background in art history had to prepare to make decisions in the specialized fields of the history of photography and nineteenth-century American landscape. The entire task of developing the exhibition and writing the catalogue could take only one semester. Decisions about the works to be shown had to be made while the class was still in the process of grasping the basics of the history of photography. The students needed time to plumb one photograph for its history, relationships, and appearance in order to write a paper and a 2500-word catalogue entry. Readings that they all shared helped them to collectively agree on generalities and on the role of photographs. The question of "artists, journeymen or entrepreneurs?" that they raised is a basic one. It has to be answered as "all of the above" by each generation that studies it in order to understand how photography became "art." A good place to start.

There had to be a limit on the number of photographs from the vast collection that would be available for selection by the students. That the quality of the work in the show was excellent was pre-determined by Steven Moriarty, the Snite Museum's recently retired curator of photography, who has been carefully developing a collection for Notre Dame. He selected seventy-five American landscapes for the students to consider. The photographs which made the student cut, and were part of the exhibition, represented a curiously lopsided distribution of photographers. Out of seventeen images of American landscapes, two were by Muybridge, four represented O'Sullivan, and six were from Brazilian Marc Ferrez. Five other photographers were included with one print each. The selection of photographs seems to have been made visually, without preconceptions about who the photographers were, or about creating a balance of images or places. The anomaly of the process was to find South America represented, with one exception, by Marc Ferrez. Steven Moriarty has been assiduously collecting nineteenth-century South American photography for the Snite Museum for some years, so it would have been interesting to see a broader range.

However, the Ferrez prints found an effective place in the progression of the show. Each of the seventeen pieces had to find a place in a visual narrative and in an historical relationship in order to fit together on the walls of the gallery. This is not an easy project for a large committee, but the final hanging agreed on by this collective was sensibly and sensitively done. Begin with the East coast of the United States, explore west, then cross borders to the south. Hang Muybridge's Yosemite shots where their dramatic, long distance presence can attract the visitor. The show reads well and allows for a variety of imaginative narratives by its viewers.

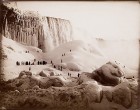

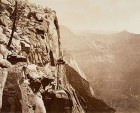

The way in which a show like this can break new ground is in the fresh juxtapositions that occur as different images are placed side-by-side, suggesting new interpretive possibilities. Barnard's Lu-la Lake (1866), which begins the exhibition, is nature without human figures, but not devoid of the baggage left by human habitation (fig. 3). Fallen building timbers can be found among broken trees. The water is serene, but there is much to be repaired. The time is immediately after the Civil War, and the lake was close to terrible battles. The next photograph, George Barker's Niagara Falls in Winter (1885), is full of people (fig. 4). The tiny antlike figures of sightseers stand in stupefied admiration of great dunes of frozen spray and the expanse of the falls above. Awe and wonder become themes. The Muybridge images of Yosemite are similar in their subjects, but different in their sensibilities. In The Domes, Valley of the Yosemite from Glacier Rock (1872), a layered landscape seen from a high point of view moves in stately progression across a broad valley and past framing peaks (fig. 5). The world is clearly laid out before the beholder, awesome but not threatening, concomitant to contemporary paintings by Bierstadt and Church. Very different is the equal division between near and far, the point of view from slightly down the cliff, of Yosemite Cliff at Summit Falls (1872). This more radical framing forcefully accentuates danger and the unexpected (fig. 6).

The four O'Sullivan works were next and had contrasts among themselves. The drama of the monumental cliffs of Cañon de Chelle (1873) played against the low and blocky plainness of Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico (1873) (fig. 7). They were a visual reminder of the varied landscapes that photographers encountered as they traveled. The low and blocky pueblo was a mountain compared to the successive flat planes laid out in the neighboring print by William Henry Jackson, Chihuahua (Mexican Railroad) (1884) (fig. 8). Human communities become abstract forms. Not awe and wonder, but peace and calm.

The explorations of the exhibition have now traveled west and south to Mexico as well as to another corner of the gallery. There, it takes a turn and finds itself in South America (fig. 9). Exploration is the motif and motive in Along the Orinoco River, Venezuelan Amazon (ca. 1886–1887), a photograph of a surveying party led by Jean Chaffanjon (fig. 10). The company fills up the middle ground, most of them up to their knees in water. Their small boats cluster behind them, and the group is closely framed by jungle. O'Sullivan's photograph of Apache scouts (View on Apache Lake, Arizona: Two Apache Scouts in Foreground, 1873) puts them closer to the foreground, but they are few and seem at home where they are. Chaffanjon and his comrades appear caught in a mire. However, their lengthy expedition to map the Orinoco more than fulfilled its goals. It takes a moment's observation to realize that they are not caught in jungle darkness at all, but that light is streaming through from overhead.

The photographs by Marc Ferrez make an interesting finish to the exhibition. In each work, the infrastructure of humankind permeates the landscape (fig 11). For instance, he catches a tram climbing diagonally upwards on a bridge that runs across a lush landscape in Pont de Sylvestre, to Corcovado (ca.1895). He takes us, or the works chosen for the show take us, to huge mountain reservoirs and local aqueducts. People are not featured, but they are definitely present. The final piece in the show is much smaller than Muybridge's Yosemite Cliffs, but has a similar impact. A bottomless mountain crevasse in the foreground confronts us with danger, but there appears to be a bright destination beyond the next mountain (fig. 12). However, this is not a landscape devoid of human presence. Tiny and tucked in the upper right of the photograph high on the neighboring slope is evidence of a railway cut that enters into a tunnel, the safe and easy access to that world beyond. (Tunnel De Sanga Funda, Estrade De Ferro Paranaguá-Curitiba, ca. 1884)

The seminar was on its own voyage of inquiry. The participants were not instructor led, but instructor guided, so they were finding their ideas and themes as they went. The catalogue entries are not startlingly new, but they are fresh with the sense of discovery. The repetition of certain ideas and history were inevitable. After all, there were similar social and historical issues for the photographs. The occasion of the photograph and the backstory of the photographer are all included, making the catalogue a useful tool for someone beginning the study of the history of photography. Other issues that were becoming apparent to the class emerged in the catalogue as well. Barker's Niagara, Haynes' Yellowstone, and Muybridge's Yosemite all have their place in the debates about how to preserve natural settings. These stories are separately told in individual entries, but collectively they add to our understanding of the development of the National Park system. The seminar students also became aware of how the exploration of the Americas hemmed in the Native Americans, and how mapping expeditions were part of territorial expansion and the eventual appropriation and exploitation of natural resources. In particular, the photographs of Ferrez document the alterations of the natural countryside made for the sake of modernization and for the needs of city and industry. For this reason his work fits well at the end of this journey through the Americas.

Individual articles provided interpretations of particular photographs, but the arrangement of this group of photographs became the collective history written by the seminar. The visual selection that had been made early on had become the story of the expansion of Europeans into the natural landscape and the eventual industrialization of that landscape.

Marjorie Schreiber Kinsey

mkinsey57[at]sbcgobal.net