The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Johan Thorn Prikker - de Jugendstil voorbij (Beyond Art Nouveau)

Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam

November 13, 2010 – February 13, 2011

Museum Kunst Palast, Düsseldorf (Mit allen Regeln der Kunst: Vom Jugendstil zur Abstraktion)

February 26, 2011 – August 7, 2011

Publications:

Johan Thorn Prikker: De Jugendstil voorbij.

Edited by Christiane Heiser, Mienke Simon Thomas and Barbara Til.

Brugge: Drukkerij Die Keure, 2010.

256 pp.; 262 illustrations, bibliography, index.

34 €

ISBN: 9789069182506

Johan Thorn Prikker, Mit allen Regeln der Kunst: Vom Jugendstil zur Abstraktion.

Edited by Christiane Heiser, Mienke Simon Thomas, Barbara Til.

Brugge: Drukkerij Die Keure, 2010.

256 pp.; 262 illustrations, bibliography, index.

36 €

ISBN: 9789069182513

Beyond Art Nouveau is the title of the exhibition that the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam has dedicated to the artist Johan Thorn Prikker (1868 The Hague, The Netherlands–1932 Cologne, Germany) (fig.1). Thorn Prikker has been a highly controversial artist ever since he left the Netherlands in 1904 to pursue success in Germany. While Dutch art history has concentrated on his Dutch oeuvre, German art history has thus far usually focused only on Thorn Prikker's German legacy. Dr. Christiane Heiser, the guest curator who wrote her doctoral dissertation on the artist, has tried to show Thorn Prikker's work in all its richness with an exhibition that integrates his art works from both sides of the border. The show crosses national boundaries to demonstrate how an integrated view of an artist's work gives more insights into his oeuvre, but also into the artist himself.

Thorn Prikker became popular in The Netherlands in the 1890s for his symbolist paintings and drawings. In the same period he began designing furniture, making his art nouveau creations a sensation in The Hague. However, tensions within the Dutch avant-garde circles and a tempting offer in Germany led him to cross the border. Here, he developed his art and became a groundbreaking designer of stained glass, mosaics and wall paintings. Artistic successes during these years led him to request German nationality in 1914. The Dutch public, which regularly despised Thorn Prikker, would later learn to admire his works thanks to the German appreciation for this artist, and would commission and acquire his creations.

The exhibition, Johan Thorn Prikker: Beyond Art Nouveau, constituted an all-encompassing show. The Dutch and German legacies—paintings and drawings as well as the arts and crafts productions—hung next to each other according to a transnational and multidisciplinary approach. By addressing the art works in this way, the exhibition successfully raised questions of national identity and the categorization of the arts. The title, Beyond Art Nouveau, not only ensured commercial success through the appeal of "art nouveau," but also seemed to push the art nouveau lexicon forward by using the description of "beyond" in order to circumscribe all of Thorn Prikker's works (fig. 2).

The controversial Dutch-German tension prevalent in his oeuvre was not reflected in the exhibition, although Thorn Prikker's physical migration was easily noticeable in the six chronologically organized sections focused on the six cities where he worked and lived. These were The Hague in The Netherlands, and Krefeld, Hagen, Munich, Düsseldorf, and Cologne in Germany. The artist's transnational life and work was under-represented in the brief exhibition pamphlet, which ultimately resulted in a superficial analysis of the artist's works. While this superficiality was the intent of the curators, the exhibition still lacked the intellectual challenge that some visitors may have appreciated. This situation is not unique since it regularly takes place in art exhibitions where the institution prepares a depthless presentation of a topic for the broad audience at the exhibiting space, and an academic presentation in the form of a symposium and catalogue for the academic elite. Surely it is not impossible to add archival insights, academic information, or broader contexts to the show itself. As it stands, this exhibition chose to separate the general and the academic presentations, increasing their mutual alienation.

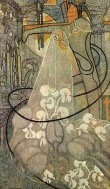

The Anarchist Worker Makes Art Nouveau

The opening area highlighted Johan Thorn Prikker's status as a symbolist and anarchist artist, and as an art nouveau designer in his last years in The Hague (1868–1903). Preceded by a few peasant paintings and drawings à la Millet, the symbolist painting The Bride hung next to other two symbolist canvases in a triptych composition (fig. 3). It was an eye-catching prelude to the symbolist sub-section, The Bride being one of the most renowned paintings from the artist (fig. 4). A large central space provided several examples of Thorn Prikker's designs from when he was the artistic leader of the art and interior design shop, Arts and Crafts, at The Hague in the late 1890s (fig. 5). There, he assimilated traditional craftsmanship techniques and designed various batik fabric, furniture and lithographs.[1] "The Hague Interior" contained a wooden couch, several chairs, a table, a closet, a lamp, a cot and several of his batik fabrics lying on tables. Exhibition curator Dr. Mienke Simon Thomas (Museum Boijmans van Beuningen) intended this first of two large spaces to create a special sphere by evoking real places, in this case the interior of the shop in The Hague.

Thorn Prikker's anarchist orientation was the third element conceptualized in this section. The artist considered art first and foremost as manual laborer, and, therefore, perceived himself as an artist-worker. He created art that could influence the life of the viewer, awakening and moving him towards revolution. A certain messianism was made evident by his political aesthetics in the figure of Christ, who appears in several drawings depicted as a suffering humble man. It resonated with Thorn Prikker's rendering of men working in many other drawings. The figure of Christ operated as a stringent metaphor for the coming anarchist order as imagined by the artist. Neither anarchism nor the figure of God were further explained, and the interesting relationship between these two elements in the eyes of the artist is also missing from the wall texts; the exhibition catalogue, however, has a whole chapter devoted to these issues.[2]

The artistic quality of Thorn Prikker's works cannot be easily correlated to their success. Commented upon in an exhibition catalogue of 1968, his work was somewhat of a displacement in Dutch visual culture.[3] Christiane Heiser also stressed this point in the presentation. This out-of-tune characteristic was seen in the last subsection within the section on The Hague, which displayed a series of drawings of rural landscapes featuring bright chromatic compositions executed with vibrating strokes. These proto-expressionist works certainly shocked the contemporary Dutch audience only just adapting to the works of The Hague School (not having developed a taste for Impressionism yet). Moreover, the question of "Dutchness" in The Netherlands at the end of the nineteenth century was a highly fluctuating concept; nationalism was at its peak, but the terms of its expression were still under discussion. What happened before with The Hague School works, first admired abroad rather than in the Netherlands, happened again with the work of Thorn Prikker. The following section showed the artist's work made in the country where it was appreciated: Germany

A New Language to Express the Same Message: Monumental Art

This area presented a new period in Thorn Prikker's career, focusing on a series of experimental directions (fig. 6). When the artist moved to Krefeld, Germany, in 1904, he went to work as an art lecturer at the new School of Applied Arts, accepting the invitation of Friedrich Deneken, Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum, Krefeld. Besides teaching, he painted animal watercolors, designed posters and textiles, and developed weaving techniques for the city's textile industry. His greatest achievement of the period was, however, his monumental art.

Wall painting was in full bloom in turn-of-the-century Germany. Even more, it constituted a subject in the Arts and Crafts school where Thorn Prikker lectured. These factors, in combination with his concern for creating art for the people, led to the artist's active engagement with monumental art. With wall paintings dedicated to religious subjects, Thorn Prikker aimed to reach a greater audience. The cartoons for The Sower and The Blind constitute a fine example of the subject matter chosen by Thorn Prikker and the abstracting treatment he used to depict them (fig. 7). These cartoons hung prominently in the exhibition. They were next to each other against a wall with two color planes, light pink from the floor to the midpoint of the wall, and white from the midpoint to the ceiling. This progress of the wall's color from dark to light emphasized the great size of the works, suggesting the opposition of the monumental work against a horizon-like view.

The years in Krefeld were an intensively productive period for Thorn Prikker, who realized approximately twenty cartoons as designs for possible commissions.[4] Official assignments were most likely to come from Krefeld's bourgeoisie, the social class that owned capital for home decorations, but the majority of the cartoons were never used for real projects.[5] Dr. Lieske Tibbe, Radboud University, Nijmegen, commented on this interesting subject during the conference at the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam, on January 28, 2011. She discussed the paradox of monumental art, emphasizing how it worked against traditional bourgeois art while, in fact, needing wealth in order to materialize. Nonetheless, as Simon Thomas stated, there was no necessary contradiction between anarchism and the wealthy bourgeoisie; both W. J. H. Leuring and H. P. Bremmer (1871–1956) were bourgeois and anarchist, commissioning Thorn Prikker to embellish their villas. Crucial as it seems in understanding the large number of unfulfilled projects in this period, the question of patronage was dismissed in the show.

After Krefeld, Thorn Prikker moved to Hagen (1910–1919). He went on designing cartoons for wall paintings there, but he also ventured into new techniques like mosaic. Thorn Prikker's practices in both Krefeld and Hagen were multiple and fruitful, and they were generously displayed in the exhibition space that interconnected the cartoons in a colorful environment (fig. 8). Beautiful animal watercolors, fabric designs and weaving techniques were put on display, accompanied by concise explanations of style and artistic method (fig 9). These explanations appeared on wall texts, which also introduced the visitor to Symbolism, political drawings, batiks, stained-glass technique, mosaics, and vestments. The last area of the Hagen section presented several mosaic designs and even some mosaics that the artist made as trials for monumental projects (fig. 10). Interestingly enough, hidden behind the mosaics, there was a corner where three portraits were hung (fig. 11). They represented Anna Henry (Kröller-Muller Museum), Mrs J. E. Cronmelin-Tritein Nolthenhuis (Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam) and Gottfried Heinersdorff (private collection), painted in plain colors. The first two appeared in profile, in a fashion similar to Renaissance medals. These portraits conveyed a rather inglorious moment in the artist's career when he accepted such commissions in order to earn his living. Their marginal placement in the exhibition furthermore seemed to reflect upon the shame that accompanies such commercial artistic production.

Thorn Prikker's Art Becomes Official

The last area comprised both ecclesiastical commissions and assignments for public buildings, thus the artist's official art period. The scale of the projects and the masterly way of combining ornament and figures made him the most important master of modern glass art in the 1920s, according to Heiser.[6] The works he executed during the following twelve years underscored Thorn Prikker's artistic maturity.

This area of the exhibition constituted a representative display of ecclesiastical commissions. There was an interesting transition between the artistically heterogeneous production of the artist from Krefeld and Hagen and the homogeneous production of the last area, which was stained-glass work. The mobile modules placed in the exhibition space formed a corridor between the last section and the temple in the next one (fig. 12). These modules played a key role in the show. They functioned first as walls to hang artworks on when there was no real wall available to use but the section still required more exhibiting space. Second, some of the modules also provided a table-like element to display the material horizontally (books, fabrics, pictures, etc.). Third, they defined the boundaries between different sections, and fourth, they determined the path of the visitor by creating corridors. In addition, curator Simon Thomas admitted that they were extremely useful for the staff when choosing the placement of the works; their mobility allowed the staff to try several combinations before deciding the final design of the show.

The aforementioned corridor displayed different kinds of work, like ecclesiastical vestments and marquetry boxes (fig. 13). At the end of the corridor was the entrance to the temple, which constituted the second "special sphere" of the show (the aforementioned Hague Room being the first). The temple consisted of a white cube on the outside that turns into a black cube on the inside. The inner space comprised an entrance hall and a main hall, both decorated with colorful stained-glass windows presented in a miscellaneous logic (figs. 14 and 15). The neutrality and darkness of the black color enhanced the richly designed windows and made their color compositions look brighter. This effect was also reinforced by the external lighting of the exhibition space, in which the lights became progressively lighter and darker to give the feeling of the real vanishing of the daylight and to show how the colors varied with changing light intensities. The result was a sort of mystic capsule where the beautiful windows magnetically attracted the visitor's gaze and provide him or her with an aesthetic experience.

Munich was the city where Thorn Prikker spent the next three years after Hagen (1920–1923). The artist was again invited to teach monumental art at the city's art school. This period confirmed his artistic recognition not only in Germany, but also in The Netherlands. The wall text informed the visitor that Dirk Hannema, director of the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen at that time, acquired Thorn Prikker's rejected designs for the decoration of the City Hall in Rotterdam in 1922 (fig. 16). This action was likely motivated by the artist's promoter, H. P. Bremmer (1871–1956), who was an art collector, critic and dealer. He advised the art collector Helene Kröller-Müller (1869–1939) as well to purchase Thorn Prikker's work, and thanks to these initiatives, several very fine works from the artist have remained in Dutch territory. Thorn Prikker received an important commission to decorate the Burgerzaal of the City Hall in Rotterdam when he already resided in Düsseldorf (1923–1926). He worked for two years on six great canvases and two smaller pieces in his German studio, and brought them after their completion to their final destination. Their subject matter was Rotterdam's harbor, not surprising as this area designated the main commercial activity of the city. Executed in a decidedly flat and rough way (at times purposely unfinished bits surface on the canvases), the paintings constituted a tribute to the hard-working people who kept the city's economy going.

The resulting decoration of the Burgerzaal appeared on film, played in a loop, next to the section featuring the rejected designs of the former commission (fig. 17). The three-minute clip showed the building of the City Hall in Rotterdam, the Burgerzaal, and finally the eight canvases painted by Thorn Prikker. This cinematic resource worked remarkably well as it showed other works of the artist that were relevant, but could not physically be added to the exhibition at the museum. Several other videos featured in the exhibition had the same illustrative role (fig. 18). Short but compact, they provided beautiful images of the missing works. The presentation of these videos, in combination with their illustrative function, turned them into windows to the outside, thereby establishing an interesting dialogue between the material confines of the museum and the wider topography in which Thorn Prikker's work manifests. The smart integration of the films in the exhibition space not only made the visitor's experience more dynamic, but also avoided the common mistake of placing a film room at the end of a show with a long film that the visitor is not going to watch.

Düsseldorf and Cologne (1926–1932) were the artist's last two cities of residence. The sections devoted to this period displayed designs for stained-glass windows as well as examples of finished pieces (figs. 19 and 20). For instance, the Essen window hung next to a similar earlier design from 1925 (figs. 21 and 22); although the window was never materially realized by Thorn Prikker, his design was used in 1965 to create the final window. All the stained-glass windows in the show hung against a wall with two color planes, again in order to highlight the idea of monumentality (as has been noted with the cartoons for monumental art). The pieces were meticulously illuminated to show the full mastery of the designs. Despite the lively atmosphere this lighting produced, the sections on Munich, Düsseldorf and Cologne compared rather poorly to the first three sections. It is evident that Thorn Prikker's later work presented curatorial difficulties since many windows, mosaics and wall paintings could not be removed from their permanent places. Furthermore, a considerable part of his legacy was bombed during World War II, like the City Council of Hagen and the headquarters of Philips in Rotterdam.[7]

The exhibition closed with a long glass table displaying the literature available on Thorn Prikker prior to this show (fig. 23). Dr. Christiane Heiser was intent on having a sample of books on display for the visitor to realize how much already has been written on the artist, yet how narrow the nationalistically oriented approaches were. The table's presence sought to legitimize the exhibition itself for its aim to present a corpus of the artist's work in an inclusive way. The bibliographical section provided the visitor with the right mood to attend the academic conference given in the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam, with a follow-up event at the Museum Kunst Palast in Düsseldorf. Both conferences shared broad research areas while they explored different case studies. The research areas were "Collecting Thorn Prikker," "Thorn Prikker and the avant-garde in Holland and Germany," "New perspectives on monumental art," "Fine art, arts and crafts and design," and "National identity and the canon of Modernism." The first-class speakers led the discussion of several topics and made the figure of Thorn Prikker appear in all his richness and complexity.

In addition to the conferences, there is an exhibition catalogue that includes several of the presentations and adds the research of other professionals who did not participate in the lectures and debates. The catalogue shares the title of the exhibition and contains fourteen academic articles (fig. 24). The articles are thoroughly written and present highly specific aspects of Thorn Prikker's work. With this inclusive catalogue, it is difficult to imagine the publication of another book on Thorn Prikker in the near future.

Johan Thorn Prikker: Beyond Art Nouveau was a beautiful exhibition. The intelligent placement of the mobile modules structured the sections within the squared exhibition space and suggested a clear path to the visitor. The presence of films throughout the show constituted refreshing instants that entertained the visitor and expanded the information on the works. In addition, the inclusion of label texts to explain the different artistic techniques that the artist used was very instructive. The metaphor of the monumental art works breaking the ceiling by the combination of two color planes worked brilliantly. Finally, the placement of the "special atmospheres" helped the visitor envision how some of Thorn Prikker's works actually functioned in their real environment, instead of in the aseptic windows of the exhibition. The recreation of the temple especially made the visit more participatory, allowing the visitor to experience the magic of the windows in the interior of a temple.

The exhibition established an aesthetic tribute to the artist. His work was tastefully displayed although his life remained a succession of moving from one city to another. The strong focus on the visual left the visitor with some certainties, but very few questions. The provocative spirit of the approach already mentioned did not lead to a provocative exposure of the works and the information related to them. Johan Thorn Prikker: Beyond Art Nouveau was a good exhibition even with its shortcomings. Surely its legacy will foster discussion of exhibition practices, and hopefully will lead to a more balanced exposition of artwork and intellectually challenging information.

Alba Campo Rosillo

MA Art History candidate

alba[at]albacampo.com

[1] Christiane Heiser, "Johan Thorn Prikker (1868–1932). Een kunstarbeider' op zoek naar sociale gerechtigheid en religieuze ervaring" in Johan Thorn Prikker - de Jugendstil voorbij, Christiane Heiser, Mienke Simon Thomas, and Barbara Til, eds., (Brugge: Drukkerij Die Keure, 2010), 18.

[2] Ibid., 8–39.

[3] J. M. Joosten, Johan Thorn Prikker (1868-1932): schilderijen, tekeningen, litho's, glas-in-lood ramen, mozaïeken, inlegwerk. Catalogue Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, nr. 443 (Amsterdam: Stadsdrukkerij, 1968), 38. (Catalogue of the exhibition held from September 6–October 20, 2010 at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, with the title: Johan Thorn Prikker).

[4] Martina Padberg, "Terug naar de toekomst. De periode Krefeld: van toegepaste naar monumetale kunst" in Johan Thorn Prikker - de Jugendstil voorbij, 98.

[5] Ibid., 102.

[6] "Art Nouveau artist Johan Thorn Prikker fled the Netherlands," University of Groningen News (October 6, 2008), http://www.rug.nl/Corporate/nieuws/archief/archief2008/persberichten/122_08 (15/01/2011)

[7] Heiser, Christiane, "Johan Thorn Prikker (1868–1932). Een 'kunstarbeider' op zoek naar sociale gerechtigheid en religieuze ervaring" in Johan Thorn Prikker - de Jugendstil voorbij, 36.