The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Japanese Cloisonné Enamels: The Seven Treasures

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

June 13, 2011– August 19, 2012

Catalogue:

Japanese Cloisonné Enamels: The Seven Treasures.

Gregory Irvine.

London: Victoria and Albert Publishing, 2011.

96 pgs; 89 color illus; bibliography; index.

£9.99

ISBN 978 1 85177 657 3

Although the Meiji era in Japan has received considerable scholarly attention in recent years, the importance of cloisonné enamels that flourished in Japan during this period has been neglected. In an effort to remedy this lacuna, Gregory Irvine, Senior Curator in the Victoria and Albert Museum, has mounted a superb small exhibition of cloisonné objects drawn from the museum's recently received collection of pieces through the generous donation of Edwin Davies. In this show and in the catalogue that accompanies it, Irvine has charted the history of cloisonné enamel, demonstrating how prevalent the interest became once Japan started producing a wide range of objects to meet the insatiable demands of the West for objects in this material. But the exhibition is much more than simply an examination of objects from the Victoria and Albert collection (fig. 1). Through a careful selection of pieces, Irvine has been able to reveal the different types of cloisonné enamels, explaining how the creation of pieces were technically modified, and divulging the names of the principal creators and firms so as to provide a history of cloisonné enamels that deeply affected western artists in England and in France.

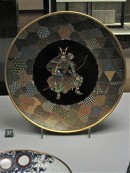

The show began with a series of pieces that were selected to reveal how cloisonné enamels were made. In the same vitrine, Irvine positioned examples that charted the evolution of cloisonné creativity from the eighteenth century to examples produced in the early nineteenth. In each instance he chose pieces that showed changes in coloring and in the selection of the motifs utilized (fig. 2). Historical phases were united with the rediscovery of pieces purchased early on by the Victoria and Albert Museum from collectors in France, including an incense burner or brazier produced in Nagoya (1865–70), which came from a series of works purchased in 1875 from the famous Parisian art dealer, Siegfried Bing (fig. 3). Other pieces, such as a silver dish with a central image of a samurai, were purchased from Arthur Lasenby Liberty, Bing's counterpart in London who displayed early on a passion for Japanese art, and who was able to promote the taste for Japanism through his famous store (fig. 4). These early pieces, placed at the beginning of the exhibition, helped set the foundation for the continuing examination of the golden age of cloisonné enamels that took place between 1880 and 19l0. A large part of the exhibition was devoted to pieces produced by single artisans or firms; it is thanks to Irvine's historical acumen and sensitive eye that the installation of so many examples added to our awareness of the Japanese craftsmen of this era.

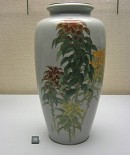

Examples from the golden age were numerous, varied in motif, and were selected because they contributed to the history of the movement by revealing the ways in which different artisans worked and how various companies reflected the interest in producing numerous pieces for export ware (figs. 5–8). As cloisonné became more sophisticated, individual designers who were in charge of studios, such as Namikawa Yasuyuki, dominated. Their works were characterized by "intricate wirework and the superb attention to detail." The scenes on vases became more naturalistic, suggestive of vignettes from actual landscapes drawn from scenes observed near Kyoto. Views such as these had a definite influence on European ceramic makers who not only borrowed from Japanese prints, but also were becoming increasingly aware of cloisonné enamels as a source to assimilate and appreciate.[1] Shown at major international exhibitions in Europe, Japanese enamelware had a powerful influence on collectors and on businessmen who recognized that there was a strong interest in obtaining pieces for European interiors.

While Irvine notes in his catalogue essay that a huge number of inferior cloisonné pieces were produced to meet the insatiable demands of popular consumption, his exhibition took a higher road. Almost all of the examples that were exhibited were of considerable aesthetic value and creativity, demonstrating just how varied the types of cloisonné enamels were. Even the technique of plique-à-jours enameling was represented in the exhibition, a form of creativity where the Japanese, under Ando Jubei, might have been influenced by European sources as they enlarged their sphere of influence during the Meiji era with reciprocal assimilations that made their art work more competitive with the West.

Although the assimilation of cloisonné enamels in the West was not directly addressed in the exhibition, the fact that a broad range of pieces had been placed on display was duly noted. The technical aspects of their creativity was discussed in concise, but well developed wall and case labels, presenting curious visitors with considerable room for speculation as to the impact these pieces had on artists both in the decorative arts and in painting. It is exactly this type of small, didactic show, covering material seldom studied by art and cultural historians of the nineteenth century that can help broaden the way in which Japanese influences have been perceived. Not every aspect of a Japanese influence in the West can be traced to the presence of ukiyo-e prints. In this show there is ample evidence that enamels from Japan, some produced for export ware, were widely available. They challenged western artists to think in new ways by nurturing innovation that inspired western creativity. The exhibition was not only a delight for the eyes of connoisseurs, but also challenged contemporary Japonistes to look beyond the often-examined influence of the Japanese print medium and to include more thoroughly that of the decorative arts.

Yvonne M. L. and Gabriel P. Weisberg

vooni1942[at]aol.com

[1] Philippe Burty, Les Émaux cloisonnés anciens et modernes (Paris: Chez Martz, Joaillier, 1868).