The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

An American Journey: The Life and Photography of James Presley Ball

Cincinnati Museum Center, Cincinnati, Ohio

May 1–October 24, 2010

Last summer the Cincinnati Museum Center (CMC) assembled a significant exhibition, the first extensive display of daguerreotypy and photography by James Presley Ball (1825–1904). All holdings were from the Cincinnati Historical Society (part of the CMC), which houses the nation's largest collection of images by Ball and his partners, numbering over 400. The compilation covers almost his entire career, which lasted over fifty years and took him from coast to coast in the United States, as well as to Hawaii and Europe. Ball was an award-winning artist, celebrated internationally for his portraits of well-known whites, African Americans, and Asians. His sitters included such celebrities as Frederick Douglass, Jenny Lind, and Ulysses Grant's family. The exhibition featured sixty original images.

Since Ball began his career in Cincinnati and spent a quarter century there (ca. 1845–1871), it was appropriate that the show accentuated those early years. An American Journey, although a modest historical display in the John A. Ruthven Community Gallery, was a non-ticketed show that admirably met its goal of raising local awareness about the numerous artistic and entrepreneurial talents of this remarkable African American man. Lamentably, due to a shortage of funds, the CMC was unable to advance scholarship in the form of a catalogue or generate wider interest by traveling the exhibition nationally, as originally intended.[1] It, however, did include much new information unearthed since the publication of Deborah Willis's book, J.P. Ball, Daguerrean and Studio Photographer (New York, NY: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1993), and presented this in text-heavy wall labels.

An American Journey appeared in a 900-square foot peripheral gallery on the lower level of the Cincinnati Museum Center located in the acclaimed art deco Union Terminal train station (1933). Because the Ruthven Gallery is underground, there is no natural light. Although the low light level was admittedly necessary for displaying fragile, light-sensitive works over six months, the exhibition's introductory space was drab, dark and cramped. The lack of original photographs in this area and the dull installation in a shallow space only reinforced a cave-like and unwelcoming atmosphere at the entrance to the show (fig. 1). Granted, the CMC did the best it could with its restricted budget, borrowing relevant props from the historical society.

The first scene was an approximation of Ball's "Great Daguerrean Gallery of the West" at No. 28 West Fourth Street in Cincinnati, based in very limited form on a woodblock illustration from Gleason's PictorialDrawing-Room Companion (April, 1854). An enlarged facsimile of that print hung on the back wall for reference. It depicted fifteen white appreciative clients in a large, elegant reception room furnished with a piano, five oil paintings by Cincinnati African American landscapist Robert S. Duncanson (1821–1872) (who worked for Ball as a retouch artist), and at least forty-two photographs by Ball. By contrast, the studio simulation had just four items—a red, theatrical drape; a heavy metal head brace with U-shaped clamp; an upholstered chair with carved wooden frame; and a potted artificial fern atop a column. The header of a placard on the platform, with an enlarged reproduction an unidentified carte-de-visite (cdv) portrait taken in Ball's studio, announced that these are "A Victorian Photographer's Props." An arrow superimposed on the photograph points to the bottom of the neck brace behind the legs of the standing client, who needed the support to help keep still during the long exposure time, which could last up to a minute.

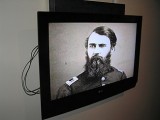

The large introductory wall label featured the only known photograph of the bald, long-bearded, and light-skinned Ball, taken from Esther Hall Mumford's book, Seattle's Black Victorians, 1852–1901 (1981), itself copied from a Washington newspaper. Rather patronizingly, the text stated, "Even an African American photographer could succeed if he could learn to attract white clients who wanted to sit for their portrait." It explained that Ball was a middle-class entrepreneur in a small community of African Americans, who arrived in the "Queen City" in 1845. Also known as "Porkopolis" (because of the prosperous pork industry), Cincinnati was the fastest growing city in America at that time, connected to rapidly growing markets by railroad and steamboat; the city is located in the southwest corner of the state, on the banks of the Ohio River, then the border of slavery. Ball was an abolitionist who sought to educate people about the horrors of slavery. One way he did this was by commissioning a team of African American artists to create a 2,400-square yard painting, "Ball's Splendid Mammoth Pictorial Tour of the United States, Comprising Views of the African Slave Trade; of Northern and Southern Cities; of Cotton and Sugar Plantations; of the Mississippi, Ohio and Susquehanna Rivers, Niagara Falls, & C." (1855). He exhibited the unprecedented work for profit both in Cincinnati and at Boston's Amory Hall. Alas, the amazing canvas no longer exists and there are no images of it. However, Quaker Achilles Pugh printed a fifty-six-page pamphlet that describes the thirty scenes that range from Africa to the southern ports of Charleston and New Orleans, moving north through various cities to freedom in Queenston, Canada. A copy of the original publication was on display in a small case to the left of the label. Thus, Ball had several goals with this project. Clearly, he wanted to promote the cause of abolition by illustrating the breadth and depth of the slave trade in the western world. The panorama would have been appreciated in a city known for anti-slavery activity; Lyman Beecher and Calvin Stowe (Harriet Beecher Stowe's husband) taught at the Lane Theological Seminary, and Stowe based some of her novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852) on Cincinnati; she lived there in the 1830s and 1840s. Further, Cincinnati was home to ardent activists, such as lawyer Salmon P. Chase, "attorney general for runaway slaves," Levi Coffin, who sheltered black fugitives with his wife, and the afore-mentioned Pugh, who published The Philanthropist, an abolitionist newspaper, from 1835 to 1843 with editor James G. Birney, a former slave owner. Additionally, the Anti-Slavery Society financed Duncanson's trip abroad.

However, Ball was also motivated financially and artistically. He clearly wanted to make a profit, and boasted that he had invested $6,000 in the project, the same amount that Leon Pomarède had put into his panorama of the Mississippi River in 1849. Ball was well aware that large paintings of that grand body of water enticed large audiences. In 1847, John Banvard bragged that he made $200,000 when he toured the "Biggest Picture in the World" (supposedly three miles long) in New Orleans, New York, and Washington, D.C., where over 400,000 people saw it. Later, Charles Dickens published a review of Banvard's endeavor when it appeared in London. In 1848, Henry Lewis also produced a panorama of the Mississippi, launching his enterprise in Cincinnati. He then exhibited the painting throughout the United States and Germany for two years. In addition to competing with these successful showmen, Ball sought to rival local daguerreotypists Charles Fontayne and William Porter with his imagery, praised for its exacting nature because he based his mammoth pictorial tour on daguerreotypes he had taken "on the spot." In 1848 Fontayne and Porter created a magnificent panorama of Cincinnati on the Ohio River in a series of eight stunning whole-plate daguerreotypes taken in Newport, Kentucky, which they exhibited at the first world's fair in London in 1851. None of these significant details appeared in the CMC display of Ball's work, but that would have made the show more text-heavy.

One walked through the exhibition in a counter-clockwise direction, around a central, freestanding wall unit. In the next section was text about Ball's beginnings as an itinerant daguerreotypist in Ohio, Pittsburgh, and Richmond, Virginia, in the late 1840s. A free man born in Virginia to free persons of color (who had married in 1814), Ball had apparently learned the still-new daguerreotype process from an African American, John B. Bailey (originally from Boston), in White Sulphur Springs, Virginia, in the fall of 1845, and first tried his hand at business in Cincinnati. He settled again in the city in 1849 and hired his brother Thomas as an operator. Later his brother Robert would also work with him, as would his father and brother-in-law, Alexander Thomas, as well as his son and daughter. Within a short time, Ball owned the largest daguerrean gallery west of the Alleghenies, and exhibited his work at the Ohio Mechanics Institute in 1852, 1854, 1855 and 1857, winning a bronze medal in the latter show.

As visitors rounded the corner, they saw two glass-topped black cases (fig. 2). In the first were nine of Ball's exquisite cased daguerreotypes—three sixth plates, three quarter plates, and three half plates, all ca. 1855 (fig. 3). The sitters in six of them remain unidentified. One featured Ball's sister Elizabeth, her husband Alexander Thomas, and their daughter Katie. Another depicted Ball's paternal grandmother, Susan. Another was a crystal-clear likeness of the pious, but fashionable Harriet Buchanan (ca. 1801–1885), wife of Robert, a grocer, industrialist, and distinguished civic leader (fig. 4). Although the labels give little information, one can see the reasons why clients found Ball's work attractive. Although many daguerreotypists enhanced the preciousness of their unique images, silver-coated copper plates, by housing them in velvet-lined leather or Union cases, Ball took extra care with polishing plates to a lustrous finish, using natural light (his studio had a skylight), posing sitters, eliciting a sense of their personality, and embossing his name and "Cincinnati" diagonally in the lower corners on brass mats. Placing a group of daguerreotypes in a case was likely the easiest and safest way to display them in this out-of-the-way environment (often unguarded), but it is a pity the portraits could not be hung on the wall at eye level and spotlighted individually.

The next wall label, "The Daguerreotype: Mirrors of Truth and Realism," included reproductions of one of the earliest daguerreotypes, Louis Daguerre's Boulevard du Temple (ca. 1839) and a carte-de-visite of Samuel F. B. Morse with one of his cameras (ca. 1871). An advertisement for Fontayne and Porter's Gallery of Daguerreotypes in the Cincinnati Directory (1850–51) stated "Prices for Pictures, all complete, from $2.00 to $20.00, according to the size and style, or richness of case and frame." That was the equivalent of $57 to $579 in 2010 dollars.

The second case in this area was beneath a large label, "Glossary of Common 19th Century Photographic Terms and Processes," with descriptions of the processes and dates of usage of albumen prints, ambrotypes, cabinet cards, cartes-de-visite, the collodion process, daguerreotypes, and tintypes. These were listed alphabetically, although the information might have been easier to digest if the processes been ordered according to dates of invention and use. Examples on display included two ambrotypes and three tintypes with personal items, such as two brass Civil War-era buttons (apparently to provide some contrast in scale and texture), a cameo brooch, and photo-jewelry pins and lockets. None of the latter items were identified as made by Ball or his partners.

Turning around, one was in the most open space of the exhibition (fig. 5). Walking to the left, one found a woman's blue geometric striped silk dress with pagoda sleeves and a lace collar in the cage crinoline style (ca. 1855). The point was to show period clothing representative of the kind Ball's sitters wore. The outfit, on a headless human form, stood next to a small round table with a Bible, as though a client were in the process of posing for a photograph. While the gown added some life-size three-dimensionality, color, and texture to the exhibition, it did not demonstrably enhance an understanding of Ball's work.

To the left was a lengthy label, "J.P. Ball in Cincinnati, 1849–1871," outlining Ball's drive and financial success, as well as his partnerships, and the half-year long trip he made to Europe in 1856, where he claims to have opened studios in London, Liverpool, and Paris. Unfortunately, those claims have yet to be substantiated; Ball does not appear in business directories or scholars' lists of photographers active in those cities at those times. It is possible that Ball had contacts abroad (he supposedly had a letter of introduction to Dickens from a gentleman in Cincinnati) and operated businesses informally, under the radar. In London, he resided in a neighborhood called the Quadrant, where a number of people of color lived. There, his daughter Estella Victoria was born in May, and Ball named her, in part, after the queen. The text does not state that, according to the London Times, Ball photographed both Queen Victoria and Charles Dickens while in England; those images have not been found. Reproduced here are Cincinnati city directory advertisements for Ball's studios (announcing his photo jewelry and willingness to take pictures of the deceased at a moment's notice), as well as a rare daguerreotype of Myers & Co. Confectioners in Cincinnati (ca. 1850). Not stated is the fact that this broke all auction records for a daguerreotype when it sold to a private collector for $63,800 in the early 1990s. This is one of the earliest known works by Ball, remarkable because it is an outdoor scene in sharp detail (the horse is not blurred in the least), and it is a shame that the original was not shown.

To the right of the dress was a wall text, "J.P. Ball & Abolition: Communicating the Horrors of Slavery to the Public" rather out of order, situated on the opposite of the introductory scene (fig. 6). The label is also duplicative, as it reproduces the cover of the pamphlet for the panorama, as well as the exterior of the Ohio Mechanics Institute, where the painting was first exhibited. The text simply says that the narrative, detailing "the horrors of slavery from capture in Africa through middle passage to bondage," would be told by unwinding the gigantic canvas before an audience. In local papers Ball's advertisements lured customers with advance publicity starting in January 1855. He stated that the panorama would "offer a most useful geographical lesson," for only ten to thirty cents. Ball claimed that thousands came to his twice-daily, two-and-a-half hour shows that took place for twelve days, beginning March 11, 1855 in Cincinnati. Sympathetic to those with lower incomes, he offered benefit showings to families, children, and schools. He then took the display to Boston's Amory Hall, starting April 30. Little of this information is in the labels.

Next is a small case with four items (fig. 7). These were the well-worn Ball family album (ca. 1860), open to envelope-like pages with openings in them holding a tintype of Thomas Ball opposite a cdv of Alexander Thomas, whose names are handwritten in graphite beneath them. Also on view were photographs of Grandma Ball (ca. 1874–75), and Elizabeth "Betty" Ball (ca. 1874–77). In the center was a lace collar, similar to the one worn by Ball's sister. The large panel above this, "Alexander S. Thomas," provided a mini-biography of Ball's brother-in-law (1826–1910), who worked as a steward on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. In November 1857, Thomas became a full partner in the business and the name of the studio changed to Ball & Thomas. Three years later the union dissolved for unknown reasons, and Thomas continued in business with Tom Ball, still under the name of Ball & Thomas. Within two months a tornado destroyed that gallery, but many white friends helped them to repair the place, outfitting it more elaborately than before. On this placard are large reproductions of a cabinet card depicting young white siblings by Thomas, and a daguerreotype of the debonair Thomas, leaning his cheek upon his fist, elbow propped on a table. It is regrettable that this arresting original was not in the show.

Crossing the room again, one encountered one of the most compelling cases in the exhibition, which displayed six cdvs, a Union Army uniform button, an ivory hair comb, a fan, two cdv albums (one open, one closed, to show the brass fittings), a copy of The Photograph Manual; A Practical Treatise (1862), and Robinson's Patent Photograph Album (patented 1865) (fig. 8). The latter was a box in which one mounted cdvs on a long piece of paper, then wound the scroll via exterior knobs and viewed the images through two oval windows on the lid. Four of the sitters are unidentified, but two African Americans' names are known, those of Edward W. Berry, a prominent caterer, and Mattie Allen. A white man, Timothy C. Day (1819–1869), is shown standing against a blank backdrop, hands in pockets and staring straight ahead. He became managing editor of the Cincinnati Enquirer in 1849 and was elected to Congress in 1854. Although the header, "Carte de Visite: The Pocket Sized Images That Revolutionized Photography," of the accompanying text doesn't make it quite clear, this case deals with "cartomania," the intense demand for inexpensive, paper cartes-de-visite in the 1850s and 1860s.

To the left of this case was a very useful map of Ball and Thomas's Cincinnati studio locations (fig. 9). The relatives had multiple places of businesses in the heart of downtown, on 4th and 5th Streets, as indicated by the circle on the city grid. Five colored dots indicated the prime real estate where the men worked, ca. 1851–1877.

Next was one of the most popular collections in the show, concerning the Civil War (fig. 10). In addition to six cdvs were two Union Army uniform buttons, a military belt, and a U. S. Army Model 1858 officer's uniform hat (ca. 1863), and a letter from General Jacob Ammen to his wife, Martha Beasley Ammen (Jan. 29, 1862), in which he asked her to buy a regulation regimental color, including a belt and socket for the color bearer, from Shillito's, a Cincinnati department store. Two of the cdvs are of individual shots of the couple (ca. 1864–66). Another is of Henry Daggett (1842–1862). Also in the case is Dagget's diary (ca. 1861–62), in which he wrote about women in Bardstown, Kentucky who smiled in derision as Union troops marched through town. Daggett died after eating "green fruit" in 1862.

The next wall label, "The Impact of Early Photography on Society," was brief, simply saying that the new medium had a transformational effect on American society, facilitating the memorialization of friends and family, changing the perception of time and history, and becoming part of the mourning and grieving process. In particular, stark photographs of the Civil War created a sensation. To drive home the point, there were two reproductions of photographs of dead Confederate soldiers on the Antietam battlefield by Alexander Gardner (1821–1882). Such personal effects and handwriting truly enlivened the display.

The "Timeline of J.P. Ball's Life" on a panoramic wall label might have been better placed at the beginning of the exhibition (fig. 11). It reproduces images already seen, such as the streetscape by Daguerre, a city directory advertisement for Ball's work, the panorama pamphlet cover, and woodblock print of Ball's studio, but also cabinet cards of unidentified white women who posed in Montana. Below this is a case of cdvs featuring Cincinnati leaders/celebrities, such as Robert Buchanan (1797–1879) (whose wife appeared earlier in the exhibition), Rev. Moncure D. Conway (1832–1907), Rabbi Max Lilienthal (1815–1882), surveyor R.C. Phillips (1811–1881), sculptor Thomas D. Jones (1811–1881), Professor William Byrd Powell (1799–1866), opera house owner Samuel N. Pike (1822–1872), and Ulysses Grant's mother and siblings, Orvil, Clara, and Virginia (fig. 12). The captions of the mini-biographies of these important people were larger than the photographs themselves, but they would be hard to read otherwise. Historical documents included a program for a performance of Hamlet at the opera house and a speech, "East and West: An Inaugural Discourse," that Conway delivered to the First Congregational Church in 1859 as he abandoned Unitarianism for his "free Church." In addition, there was a compelling cdv, a bust of Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) with his leonine shock of white hair, when he spoke in Cincinnati on January 15, 1867, accompanied by a facsimile of a clipping about the event from the Cincinnati Daily Gazette. This assemblage indicated the respect with which prominent Cincinnatians held Ball. When faced with a choice of over thirty white photographers in town, they selected him, whether out of sympathy for African Americans generally, and/or because of Ball's skill, location, impressive business, and affordability, all factors he frequently touted in local newspapers.

Rounding the next corner, one found a poignant display of family likenesses, such as the young Meader brothers, each standing in suits with their right arms resting on truncated columns, a mother cuddling her son (the Bishops), and three of the nine Graveson siblings, as well as their parents. Their father, Isaac, was a stonecutter who made the base and esplanade for the Tyler Davidson Fountain (1871). On view was a receipt from I. & W. Graveson Steam Mill and Stone Yard for services connected with the construction of the fountain. Assorted three-dimensional props included a child's cast iron top and accessories (ca. 1850) and children's leather shoes. Two of the most attractive images were delicate, hand-tinted ambrotypes of sisters Belle and Emma Dyer, wearing identical pink striped dresses. Also included were charming cdvs of brothers James and Wallace Polk, two of the few cdvs of African American children by Ball whose identities are known.

The last case, a tall diorama of sorts, featured another woman's dress, an Empire Studio camera on a tripod with glass plate holders on the ground, and a large albumen print by Thomas on the wall (ca. 1878–1886; fig. 13). One label described the development of the dry plate camera around 1871. The other gave a mini-biography of Colonel William B. "Policy Bill" Smith (1828–1914) whose photograph Thomas took sitting in a horse-drawn carriage in front of a big house. Smith was commander of the First Regiment of the Ohio National Guard. The fact that someone of such stature selected Thomas as his photographer suggests the high esteem with which Cincinnati leaders held him.

The final label, "Ball Moves South and West," traced Ball's peripatetic career. In 1871 he moved to Greenville, Mississippi, and later to Vidalia, Louisiana. (One wonders why a black man would head south during Reconstruction. Not stated here is the fact that Ball bought and sold quite a bit of real estate.) He then kept moving westward, following railroad lines, through Missouri, Minnesota, Montana (where he photographed Chinese immigrants at work, Catholic nuns, and black service men, among others), and Washington, practicing photography all the way. At the turn of the century, Ball moved to Honolulu, presumably to help relieve his crippling rheumatism. Ball had numerous adventures, challenges, and successes along the way, none of which are recounted here.

The last item in the exhibition was a screen of moving digital reproductions of the entire collection of images by Ball and his partners in the CMC (fig. 14). The photographs were sometimes cropped, or not seen in their entirety, as the camera panned from head to toe, and the images appeared somewhat compressed horizontally. Still, at least one could see a much wider range of subjects, styles, and mediums than were physically on display. Even at the rate of only several seconds per image, the video program lasted about half an hour, and it seems that no one stayed to see the whole thing.

Six CMC staff members co-curated An American Journey Scott Gampfer, Director of History Collections; Beth Gerber, Preservation Manager; Linda Bailey, Curator of Audiovisual Collections; David Conzett, Curator of History Objects; Dave Might, Exhibits Production Coordinator; and Jay Bader, Exhibit Project Coordinator. Although they did not produce a catalogue of the exhibition, there is a "capture" on the internet; one can read Ball's mini-biography and view scans of 231 of images by him and his partners on the online catalogue of the Cincinnati Historical Society Library: http://library.cincymuseum.org/ball/jpball.htm.

In sum, this was an important show that gave viewers a sense of the scope and complexity of nineteenth-century daguerreotypy and photography, using Ball as a case study. This was not a major, traveling exhibition in an art museum accompanied by a full-color extensive catalogue (as many would have preferred), but rather a brief historical introduction to an extraordinary American whose career began in Cincinnati. The curatorial team did as well as it could, with very limited space and resources. An American Journey met its mark in contextualizing Ball's work and history in summary fashion, opening the door for deeper analysis of a fascinating man, one of a small community of nineteenth-century African American photographers.

Theresa Leininger-Miller

Associate Professor, Art History and Director of the Graduate Museum Studies Certificate Program

University of Cincinnati

theresa.leininger[at]uc.edu

[1] Leininger-Miller has worked on Ball extensively since the early 1990s, has conducted research on him in twelve cities throughout the United States and in London, and has given many lectures on his career. She was a Consulting Curator for the Cincinnati Museum Center (CMC), 2002–2006, when it was jointly planning a national traveling exhibition on Ball with the Cincinnati Art Museum. The CMC won a National Endowment for the Humanities Consultation Grant (2003) and a NEH Planning Grant (2005) for the proposed show. Because the CMC did not get a $200K NEH Implementation Grant in 2006, however, the collaboration ended then.