An Evening at Anderson House

Introduction

The first part of the digital component, with the aid of floor plans and photographs, offers a virtual tour that approximates the path and experience of guests who came to Anderson House in Washington, DC, in the early decades of the twentieth century for an evening dinner party of about twelve to fourteen couples, including Larz and Isabel Anderson. The house offered a succession of rooms that guests moved through over the course of an evening’s entertainments, from arrival to greeting to having cocktails to dinner and then finally to after-dinner coffee, cordials, and conversation accompanied by live music. Each room presented guests with a different ambience and experience of design, lighting, and, most importantly, art and other objects from the Andersons’ collections, displayed prominently in carefully planned eclectic installations that served as hallmarks of their cosmopolitan identity. In each room, particular objects make reference to both their Anglo-European ancestry and their travels to places with what they regarded as exotic cultures. The tour unfolds by scanning down the page, and as you scan the photographs, clickable halos will appear. Clicking on them brings you to another window with additional information about either a specific object or the decoration of the room.

Anderson House (1902–5)

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Front façade in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington.

Anderson House, located at 2118 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, in Washington’s Dupont Circle neighborhood, was the winter home of Isabel and Larz Anderson. Designed by the Boston firm of Arthur Little (1852–1925) and Herbert W. C. Browne (1860–1946) starting around 1901, construction of the house began in 1902 and was completed in 1905. The house comprised 45,000 square feet and 95 rooms, including bathrooms, storage, and service areas. Its total cost, including land and outbuilding, was $838,000 (approximately $25.3 million in 2023). The Andersons took occupancy of the house in March 1905, several years before the furnishing and decorating of the house was completed.

Main Entrance

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Driveway, front door, and portico columns in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington.

As guests arrived for a dinner party, they were dropped off under the portico and ushered through the mansion’s broad, paneled door into the Entrance Hall or Lobby of Anderson House.

The Ground Floor

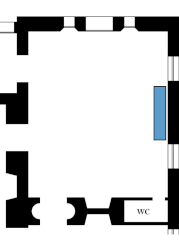

Floorplan of the ground floor of Anderson House redrawn from the original Little and Browne blueprints by Harry I. Martin III, 2015.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Entrance Hall or Lobby in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington.

This piece is described in the 1911 inventory as “1 Old bronze statue of Buddha seated in lotus blossom, right hand raised in benediction; halo decorated with figures in relief. Inscriptions on costume....Perfect.”[8] It measures 90 x 40 in. (229 x 102 cm), and in 1910 sat on a block base 52 in. (132 cm) square. The base was redesigned for its later move to an outdoor installation in the garden by the Society of the Cincinnati, as seen in this photograph. Larz described the purchase of this object in the inventory: “After having unsuccessfully sought a bronze Buddha while on trips to Japan in 1888 and 1897[.] This one was acquired from Mssrs. [A. A.] Vantine in 1903.”[9] By 1903, Vantine was a well-established New York dealer for Japanese antiques and handicrafts.

The front entrance hall, known during the Anderson era as the “Lobby,” provided arriving guests with their first view of the interior of the house. At the time of Johnston’s photograph in 1910, the Lobby was furnished and decorated sparsely with fewer than a dozen items that allude to the Andersons’s interest in and travel to Asia and Europe: religious objects from Japan and India and wooden seating from Holland and Italy.

Left: Floorplan of the ground floor of Anderson House redrawn from the original Little and Browne blueprints by Harry I. Martin III, 2015.

Right: Little and Browne (architecture firm), Entrance Hall looking west into the public side of the house in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington.

After arriving in the Lobby, guests would turn to the right and , through the door flanked by two bronze Japanese temple lanterns.

Choir Stall Room

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Choir Stall Room looking east in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington..

This room was lit by what Larz called an “Old Italian silver font-shape sanctuary lamp with pear-shape pendant of embossed figured and flutes” that was “fitted to electricity with Baccarat bead globe.”[12] On the south wall of the room, two electrified Venetian gilded polychrome torches with kneeling angels holding candlesticks provided supplemental illumination for the paintings above. These torches were acquired from the firm of Edward F. Caldwell & Co. of New York, known for providing both antique and custom-designed lighting fixtures to numerous US churches, public buildings, and residences, including the White House.[13]

A view of the ceiling and east end frieze shown with modern illumination. The emblems on the frieze above the paneling, from left to right, are the Order of the Crown of Japan; Military Order of the Spanish–American War; and Grand Officer of the Order of the Crown of Italy. The ceiling includes small cartouches and squares displaying the seals of Phillips Exeter Academy and of Harvard College, where Larz was educated, and the signal of the Anderson’s houseboat, the S. S. Roxana.

In the Andersons’ time, the Choir Stall Room was also called The Ante-Camera Stall Room or sometimes the “Inner Hall.” Serving as a transitional space between the lobby and the stairway hall and continuing the ecclesiastical character of the entry space, it was fitted with carved walnut paneling that had been removed from an unidentified church in Italy. The Andersons acquired the panels in 1905 from the antiquarian firm of E. & C. Canessa in Naples, Italy.[10]

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Choir Stall Room in 2015. Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Bruce M. White, 2015.

This 2015 photograph taken from the west end of the Choir Stall Room shows that the complexity and ornateness of the Italian woodwork and lighting fixtures harmonized with the complexity and lustrous painted surfaces above.

Main Staircase Hall or Great Stairs Hall

Floorplan of the ground floor of Anderson House redrawn from the original Little and Browne blueprints by Harry I. Martin III, 2015.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Northeast corner of the Great Stairs Hall in 1910. Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington.

Larz acquired this “Mexican carved walnut confessional chair” from the Córdoba Cathedral (Mexico, early 17th c.). In his 1911 inventory, he notes that he obtained it directly from a priest at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Córdoba, Mexico, “in exchange for a contribution to the repair of the church” that the Bishop had approved.[15] The piece measures 108 x 72 in. (274 x 183 cm). The Andersons hung a framed post card of the cathedral on the front of the confessional to document its provenance. Though the confessional may seem out of place in these secular surroundings, its decoration harmonizes with that of the Great Stairs Hall. In particular, the shield at the top of the confessional incorporates a stars and stripes design that recalls the US flag and the themes of war and patriotism in the nearby murals.

The grisaille trompe l’œil murals of the Great Stairs Hall of Anderson House were painted in 1908 by the Italian artist Oreste Paltrinieri (1873–1966). Larz described in his journal the genesis of this panel’s design: “Years ago I bought an ‘Ambassador’s Box’, a silver box with ink well and place for pens and sealing wax, such as was presented to English Ambassadors ‘on their appointment’ in the old days, although it didn’t seem then that I should ever be able to make proper use of it: -- but here it is now in its proper place: and I had ‘cheek’ enough to have this box design worked into the fresco work over the fireplace in the great staircase hall of the Washington house, to represent my career in Diplomacy (with swords, and ‘trophies’ of my own and my Father’s military services, etcetera) even before I had a right to do, or even an evident hope.”[16]

Larz described this piece as a “Hindoo antique stone idol” acquired from Watson and Co. in Bombay (Mumbai) on their 1899 wedding trip to India.[17] It measures 31 x 18 in. (79 x 46 cm). The placement of this object at a geometrically central position in a space that was otherwise dominated by Christian liturgical objects suggests Larz wished to highlight both its similarity to other pieces (religious statues) and differences from those same pieces (Hindu versus Christian, male versus female). It is now displayed on the floor in the Gallery of the piano nobile at Anderson House.

This room, known in the Andersons’ time as the Main Staircase Hall or the Great Stairs Hall, was an area where guests could remove their coats and get ready to make their way to activities on the piano nobile above.

The Great Stairs Hall continued the ecclesiastical character of the Choir Stall Room. Dark, heavy pieces of European domestic and ecclesiastic furnishings were placed at intervals along the walls, some of which referenced a specific liturgical activity like preaching or confessing. Religious figures from both eastern and western religions, secular sculptures, and architectural fragments, all placed in careful and well-spaced juxtaposition to one another, gave the Great Stairs Hall a processional, religious character that seems to reference the nave of a church.

The 1911 inventory describes this piece as an “Old Spanish carved walnut figure of a crowned Madonna and Child.” In a handwritten notation, Larz further describes it as an example of “Spanish Gothic carving,” which thus dates it to circa thirteenth to fifteenth century. The Andersons acquired this statue on a trip to Madrid in 1906.[19] During the Anderson era, it was displayed in the Great Stairs Hall in juxtaposition with the Lord Shiva and his Wife Parvati sculpture, setting up a dialogue between Christianity and Hinduism.

The 1911 Inventory identifies this object as an “Old Spanish” statue that the Andersons acquired in Madrid in 1906. Larz thought this statue might have been of Saint Margaret, a saint venerated in the Anglican Communion, of which he was a member.[20] When the item was deaccessioned by the Society of the Cincinnati in 2000, a Sloan’s appraiser identified it as possibly early-seventeenth-century Flemish.

In the 1911 inventory, Larz explains how he came to acquire six of these large Spanish tobacco jars [25 in. (64 cm) high]. The Andersons traveled to Spain in 1906 with the intention of purchasing these jars directly from the manufacturer but were unable to do so. The jars “had been sold out of a factory in Sevilla a while before our visit,” he wrote, and were already on their way to the US. By the time they returned to New York, “[the jars] were in a dealer’s hands (Watson of New York)” and they then purchased them from that firm. [21]

One of the main architectural features of the Great Stairs Hall are six columns that recall the nave of a church or cathedral, furthering the ecclesiastical character of the space already evident with the confessional and other pieces of church furniture in the room. In the 1911 inventory, Larz emphasized this connection to church architecture when he noted that, as shown in this photo, the columns were sometimes draped in “old Spanish rose color velvet panels” as was often done in Spanish churches “on ceremonial occasions.”[18] This ecclesiastical reference is also continued in the arrangement of several statues of Christian female saints and divines placed on pedestals and bases in front of columns, an arrangement that suggests the placement of statuary throughout a church sanctuary for devotional purposes.

Larz acquired this “Mexican carved walnut confessional chair” from the Córdoba Cathedral (Mexico, early 17th c.). In his 1911 inventory, he notes that he obtained it directly from a priest at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Córdoba, Mexico, “in exchange for a contribution to the repair of the church” that the Bishop had approved.[15] The piece measures 108 x 72 in. (274 x 183 cm). The Andersons hung a framed post card of the cathedral on the front of the confessional to document its provenance. Though the confessional may seem out of place in these secular surroundings, its decoration harmonizes with that of the Great Stairs Hall. In particular, the shield at the top of the confessional incorporates a stars and stripes design that recalls the US flag and the themes of war and patriotism in the nearby murals.

Larz described this piece as a “Hindoo antique stone idol” acquired from Watson and Co. in Bombay (Mumbai) on their 1899 wedding trip to India.[17] It measures 31 x 18 in. (79 x 46 cm). The placement of this object at a geometrically central position in a space that was otherwise dominated by Christian liturgical objects suggests Larz wished to highlight both its similarity to other pieces (religious statues) and differences from those same pieces (Hindu versus Christian, male versus female). It is now displayed on the floor in the Gallery of the piano nobile at Anderson House.

possibly Saint Margaret

The 1911 Inventory identifies this object as an “Old Spanish” statue that the Andersons acquired in Madrid in 1906. Larz thought this statue might have been of Saint Margaret, a saint venerated in the Anglican Communion, of which he was a member.[20] When the item was deaccessioned by the Society of the Cincinnati in 2000, a Sloan’s appraiser identified it as possibly early-seventeenth-century Flemish.

The 1911 inventory describes this piece as an “Old Spanish carved walnut figure of a crowned Madonna and Child.” In a handwritten notation, Larz further describes it as an example of “Spanish Gothic carving,” which thus dates it to circa thirteenth to fifteenth century. The Andersons acquired this statue on a trip to Madrid in 1906.[19] During the Anderson era, it was displayed in the Great Stairs Hall in juxtaposition with the Lord Shiva and his Wife Parvati sculpture, setting up a dialogue between Christianity and Hinduism.

Left: Harry Siddons Mowbray, Detail of The Order of the Loyal Legion Was Born Out of Cruel Civil War, 1909. Oil on canvas. Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington.

Right: Detail of Little and Browne (architecture firm), Key Room looking north into the Great Stairs Hall in 1910 showing Kannon sculpture, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington.

Left: Harry Siddons Mowbray, The Order of the Loyal Legion Was Born Out of Cruel Civil War, 1909. Oil on canvas. Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington.

Right: Little and Browne (architecture firm), Key Room looking north into the Great Stairs Hall in 1910 showing Kannon sculpture, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington.

The arrangement of the Key Room connects the Kannon to another female figure that Larz referred to simply as “the South,” a central figure in the nearby Civil War mural by US artist Henry Siddons Mowbray.[22] Both figures are in a direct line of sight to each other that suggests a tacit, sympathetic relationship between them: a figure representing compassion and mercy connected to another figure representing defeat and loss. Their relationship to each other is further established by a similarity of pose and costume. Larz described the position of the Kannon’s right hand as expressing “an attitude of blessing” [23] whereas the South uses her right hand to tender her sword to an allegorical male figure representing “War Bursting Forth.”[24] The Andersons created several installations throughout the public rooms of the house in which figures representing East and West were juxtaposed, thus contributing to the eclecticism of the interiors and emphasizing the Andersons’s cosmopolitan outlook on the world.

The Billiard Room

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Northeast corner of the Billiard Room in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington.

Located in the southwest corner adjacent to the Saloon and facing the garden, the Billiard Room functioned as a space for Larz to entertain his male guests after dinner in a club-like atmosphere with its “billiard and pool table,” brown oak paneling, comfortable armchairs, and portraits of notable Washington men hanging on the wall. Today it serves as a gallery for temporary exhibitions primarily on American Revolutionary history, the art of eighteenth century warfare, and occasionally exhibitions about the Andersons themselves. The original Anderson furnishings and decorative objects have been relocated or sold.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Northwest corner of the Billiard Room in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington.

This photograph of the northwest corner of the Billiard Room includes the pottery from a variety of Southwestern producers and locations (Zuni, Acoma, Hopi, and possibly Laguna) stacked in an orderly fashion both inside and on top of a carved wood cabinet with glass doors and arranged together with a collection of Larz’s yachting flags and photographs of yachts owned by the Andersons and by the Weld branch of Isabel’s family. According to the 1911 inventory, there were 14 pots though they are not all visible in this photograph.[26] As discussed in more depth in the accompanying article, the Billiard Room exemplifies how Isabel and Larz Anderson incorporated Native American objects into their eclectic interior arrangements as a means to convey to visitors their actual and aspirational cosmopolitan identity.

Hanging on the walls of the Billliard Room, as seen in this photograph of the Southeast corner, were sixty-nine “caricatures of well-known Washington characters,” all Larz’s acquaintances and friends, commissioned from US artist Clary Ray (1865–1916). Their current whereabouts is unknown. Larz remarked in the 1911 inventory that “this collection continually being added to painted by Clary Ray on order of L.A. Among the first, about 1906, were the portraits of Doctor Frank Loring and Mr. Hugh Legare, which were seen by L.A. and suggested the collection.”[34] Many of the portraits represent their sitters in urban male business suits with hats and walking sticks; however, several of them depict their subjects in riding or hunting attire suitable for a country gentleman and one of them appears as a chef. Although family photographs and heirlooms like those displayed throughout this room might not seem that unusual in a domestic interior, these caricatures have a more eccentric character and seem to reinforce the clubby atmosphere associated with a Billiard Room while contributing to its eclectic and ecclesiastical aesthetic, as discussed in the article that accompanies this digital component.

The whereabouts of the set of Japanese lacquerware is unknown, and there unfortunately are not any detailed or color images of it. In the 1911 inventory, it was described as “Japanese black lacquered tin set with gold lacquer decoration of typical figure scenes, and Larz added a notation in his own hand: “This very interesting and complete set of lacquer on metal acquired from Koopman (abt 1906) probably English or Dutch Chinoiserie.” There also is a note in graphite in Isabel’s hand: “sent to Weld – Brookline,” indicating that it may have been moved to Brookline after the house was gifted to the Society of the Cincinnati in the late 1930s.

Installed in the Southwest corner near the Native American pottery was a carved teak wood, Shvetambara Jain household shrine (ghar derasar).[28] The woodwork frame, seen here, would have been separated from its icon(s) and been deconsecrated prior to its arriving in the hands of the major dealer of Indian art and antiques, Watson and Co. in Bombay (now Mumbai) from which the Andersons purchased it during their wedding journey in 1899. In addition, to suit Anglo-European and US tastes, it would have been stripped of its brightly colored paint though traces remain across its surface.[29] Placed in the corner against the wall on a pedestal like a piece of sculpture, this shrine, like the Native American pottery, was divorced from its original function. It became part of the Andersons’s eclectic collection, serving as a souvenir of their trip to India. In a letter to his mother, Larz associated the wood carving on the two shrines they acquired with their visit to see the “exquisite work in marble” on the Dilwara Jain temples not far from Mount Abu.[30]

Larz’s annotation in the 1911 inventory suggests that he was particularly proud of this Jain household shrine, now located in the Great Stairs Hall at Anderson House, partly due to its rarity: “With other specimen at ‘Weld’ [the Andersons’ Brookline home] probably unique in America.”[31] However, he misunderstood its symbolism as revealed by the description of the iconography in the 1911 inventory along with Larz’s comments about it.[32] Rather than Vishnu or Buddha with elephants and nautch (court) dancers, it features a Gajalakshmi scene with elephants at the top of the universe bathing Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of wealth, fertility and prosperity, who, in turn, holds lotuses with elephants on top of them and is surrounded by a trailing vine that emerges from the mouths of two sea creatures (makaras). The Jains, who were merchants, regarded this subject as particularly meaningful and auspicious: according to the Indologist John Cort, Lakshmi “is essentially the occupational deity of the Jains.”[33] This scene frequently appears on household shrines and temples along with the door guardians (dvarapala) at the bottom of the four pillars and the “faces of glory” (kirtimurka) along the lower edge just below the door with the rosette pattern.

The display cabinet, now in the Library of the Society of the Cincinnati, measures 86 in. (218 cm) wide, 50 in. (127 cm) high, and 22 1/2 in. (57 cm) deep with 17 in. (43 cm) deep shelves in the center suitable for the pottery and 15 in. (38 cm) deep shelves on the sides. The Andersons may have removed the shelves so that they could stack the pots in the central section of the cabinet. It resembles the glass cases used for displays in natural history and anthropological museums, art museums, department stores, and at world’s fairs; however, its carved wood details, including the Ionic columns, the festoon of roses in the center of the frieze, and the rosettes on the glass doors, are more elaborate than those on many such cases and harmonize with the other wood decoration on the furnishings and the walls of the Billiard Room. For the Andersons and their guests, many of whom may have been unfamiliar with Southwest pottery, the cabinet lent a preciousness and an aesthetic value to these objects, linking them to the other decorative items in the room.

This Hopi Polychrome jar with its feather and wing motifs is attributed to the renowned Hopi-Tewa potter Nampeyo (1859–1942) or her daughter Annie Healing Nampeyo (1884–1968) and once belonged to the Andersons though there is no archival evidence that they were aware of the identity of its maker. It appears in Johnston’s photograph stacked on top of another Hopi pot with strapping and was used as a container for holding the signal (a triangular red flag with a jumping black horse) for the Andersons’ house boat, the Roxana, another example of how the Native objects were appropriated and repurposed by their elite white owners.

This Zuni Polychrome jar with a heart-line deer motif by an unknown maker once belonged to the Andersons. It is described in detail at the beginning of the article that accompanies this digital component. Given that formal harmony and balance was an important consideration in interior decoration during the Andersons’ period, it is not surprising that the colors of the pots—red, ochre, black, and white—would have harmonized with the brown oak wall panels, the inlaid oak floor, and the carved walnut furnishings throughout the room, and the reddish earth tones would have complemented the green cover of the billiard or pool table and “the green plaited silk” shades on the light fixtures nearby.[27] In addition, the natural motifs painted on their surfaces like the deer and the birds on this jar would have been in concert with the patterns and designs derived from nature and ranging from animals to flowers to leaves on the carved furnishings, the upholstery, the lacquerware, and the Jain household shrine.

This floor plan of the Billiard room indicates the careful placement of the Native American pottery along the west side of the house across from the door to the Saloon so that it would have been visible before entering the space and would have assumed a prominent position in the room. The Andersons also carefully arranged the room so that an almost triangular sightline was created among the pots, the Japanese lacquerware, and the Jain household shrine, all objects that authenticated the Andersons’ worldwide travels and their interest in what they regarded as exotic cultures.

Notes

[1] Isabel Anderson, “Home Journal, 1909,” box 11, Larz and Isabel Anderson Collection, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center, Boston University, 62.

[2] These details come from the original blueprints for Anderson House prepared by Little and Browne in 1902. Anderson Collection, Society of the Cincinnati, Washington.

[3] Larz’s Letters and Journals of a Diplomat (New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1940) contains more than two dozen references to “tiffin.”

[4] On Belton House, see Adrian Tinniswood, Belton House, Lincolnshire (London, National Trust, 1992). The similarities between Anderson House and Belton House are so marked that the latter could have been an historical source for it. The exterior façade, basic floorplans, and interior décor of some of the main public rooms of Anderson House seem to have been inspired at some level by Belton House, though there is no documentary evidence of any kind to support this observation, only the evidence that comes from the buildings themselves.

[5] See Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos, ed., Le guide du patrimoine: Paris. (Paris: Hachette, 1994), 277

[6] For a discussion of Japonisme in Boston, see Victoria Weston, ed., Eaglemania: Collecting Japanese Art in Gilded Age America (Boston: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 2019), 9 et passim.

[7] Undated Town Topics clipping (before 1911), MSS L1938D11 [Box 2], file NN18 Indian Purchases, Anderson Collection, Society of the Cincinnati, Washington.

[8] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House, Washington City” (with annotations), 1911, Anderson Collection, Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, 2.

[9] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 3.

[10] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 4.

[11] Larz Anderson, Identification of Emblems, Crests, and Family Members Referenced in the Ceiling of the Choir Stall Room, Anderson House, Washington, DC, reproduced in Self-Guided Tour Book, The Society of the Cincinnati Museum at Anderson House (Washington: Society of the Cincinnati, [n.d., ca. 1996]), [5]. A drawing (ca. 1920) in this book identifies the various emblems and crests on the ceiling.

[12] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 4.

[13] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 4.

[14] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 6.

[15] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 8.

[16] Larz Anderson, Some Scraps [Journals, 1888–1936], vol. 17, An Embassy to Japan. Across Siberia and through Korea to Happy Days and Associations in Tokyo [1912–1913], Anderson Collection, Society of Cincinnati, Washington, 10–12.

[17] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 11.

[18] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 9.

[19] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 12.

[20] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 11.

[21] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 12.

[22] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 90. The full description is: ““An Allegorical figure represents War bursting forth, while the South tends her sword and the Republic seeks to restrain her.”

[23] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 98.

[24] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 90.

[25] For a detailed list of items in the Billiard Room, see Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 17–27.

[26] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 25.

[27] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 17.

[28] Shvetambara is one of the two central branches of Jainism.

[29] The discussion of the Jain household shrine is informed by Isabel Taube’s Zoom conversation with John Cort, professor emeritus of Asian and Comparative Religions, East Asian Studies, Environmental Studies, and International Studies, Denison University, May 3, 2023.

[30] Larz Anderson, “Some Scraps—Our Wedding Journey and Our Trip to India,” 24.

[31] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 25. The other Jain household shrine they purchased on their trip in 1899 from Watson and Co. is now in the collection of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts.

[32] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 25.

[33] John E. Cort, “Connoisseurs and Devotees: Lockwood de Forest and The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Jain Temple Ceiling,” Orientations 25, no. 3 (March 1994), 74.

[34] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House” (with annotations), 1911, 23.