The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

| Please note: selected figures are viewable by clicking on the figure numbers. Publication of this article has been supported by a generous contribution from Christopher Forbes. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Empress Eugénie's Quest for a Napoleonic Mausoleum |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In a fifteen-year odyssey that changed the history of two English towns and situated France's last Empire on foreign soil in perpetuity, Empress Eugénie (1826–1920) carried out one of her most significant and politically controversial architectural projects: a mausoleum for the tombs of her husband and son. Eugénie engaged in two commissions to construct a mausoleum, originally designed as a memorial for her husband Napoleon III, which she then reconceived to include their son, the Prince Imperial. Eugénie contributed financial support for these projects, as well as meaningful aspects of their design. An examination of her patronage demonstrates both Eugénie's profound agency and the strength of her political resolve, even during her long years in exile. The mausoleum she had built in Farnborough is the only significant public monument dedicated exclusively to the Second Empire of France (1852–70).1 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| After Napoleon's capitulation to the Prussians in 1870 and the fall of the Second Empire, Eugénie, who was then regent, fled Paris and took refuge in England, where she was reunited with her husband and son. They established themselves at Camden Place, a house they rented from a friend in Chislehurst, a small town approximately 12 miles (19.5 kilometers) southeast of London (fig. 1). Living in England as exiles posed political and social challenges for the former Imperial family. While many English were sympathetic to their plight, they were Catholics in a predominantly Protestant nation and some regarded them as a threat to the Third Republic in France, thus capable of destabilizing political relations between England and the new French regime. If the family hoped for a restoration of Napoleonic rule in France, those hopes were dashed by the deaths of Napoleon III in 1873, following three operations to remove kidney stones, and the death of the Prince Imperial, Louis Napoleon, who was killed fighting in South Africa in 1879. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Beginning in 1873, Eugénie sought to raise a monument that would be worthy of the memory of one, then both men, a sepulcher that would celebrate their Napoleonic lineage. Her first project, Napoleon III's tomb, was designed by the French architect Hippolyte Destailleur as an addition to St. Mary's Church at Chislehurst (fig. 2). Destailleur had not worked for Eugénie while she was Empress and it is not entirely clear how he came to work for her in England. Perhaps they were brought together by her friend Ferdinand de Rothschild, a regular visitor to Camden Place and the patron of Waddesdon Manor, Destailleur's most significant secular commission in England (fig. 3).2 At Chislehurst, Destailleur designed a modest neo-Gothic chapel that was large enough to hold an altar and Napoleon's tomb. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For Eugénie, the negotiations around enshrining Napoleon's remains at St. Mary's were a test of her skills in diplomacy. The family had established an excellent rapport with Monsignor Isaac Goddard, who led St. Mary's parish from 1871 to 1892, but that relationship was sorely tested by controversy over where and how to bury Napoleon that arose on the day of his death, 9 January 1873. Napoleon died without formally apologizing for withdrawing the French troops from Rome, which he had promised the pope to protect during and after the unification of Italy in 1861. Napoleon's unexpected death meant that his anticipated request for absolution had not taken place. Burial within the sacred space of St. Mary's church by the highest official of the diocese was, therefore, not ensured. Bishop Danell, who led the Diocese of Southwark from 1871 to 1882, wrote to the Rector of the English College in Rome the very day of Napoleon's death, pleading for guidance:

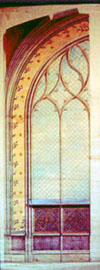

Bishop Danell received approval to officiate at Napoleon's funeral and Eugénie proceeded to negotiate the construction of a permanent burial chapel with architect Destailleur, Monsignor Goddard, and Bishop Danell. In less than five months, she approved Destailleur's plans for a chapel dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus and, in the early afternoon of the first Saturday in June, the Empress and Prince Imperial laid the foundation stone of the new chapel at a ceremony blessed by Monsignor Goddard.4 The chapel was completed by the end of 1873 and Eugénie arranged for Napoleon's tomb to be transferred from its temporary home in the main nave of St. Mary's to the chapel, which was attached to the nave's north wall, on 9 January, the first anniversary of his death, accompanied by a requiem mass.5 The tomb, a Scottish granite sarcophagus, was a gift from Queen Victoria, whose friendship with the exiled couple began as a result of diplomatic visits during the early years of the Second Empire. Officially, the chapel served as a memorial to the Second Empire and was open to the public, although for the first five years it was principally a private space for the Empress and Prince Imperial to mourn their loss (fig. 4). A small exterior door on the west wall offered them direct access to the chapel. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The iconography of the stained-glass window above this door reinforced the function of the addition as a place for personal devotions. Eugénie selected representations of five saints: John the Evangelist, Louis IX, Helen, Margaret Mary, and Henry IV. These encircle a heart surrounded by flames and rays of light that contain the intertwined letters S and H, referring to the dedication of this space as the Sacred Heart chapel (fig. 5). Clockwise from the top, St. John the Evangelist holds a poisoned chalice with a dragon in his right hand and palm leaf in his left; just as he survived this test of his faith, he triumphed over Satan. St. Louis, the patron saint of Paris, wears a crown and rests his hand on a sword. St. Helen, mother of Constantine and one of Eugénie's favorite saints, stands with a cross symbolizing her discovery of the True Cross on which Christ was crucified.6 The blessed Margaret Mary looks toward the Sacred Heart, the direction of her gaze reproducing the historical significance of her visions, which helped to establish the devotions to the Sacred Heart that were authorized in 1765. Henri IV holds a flag and bird in his right hand and a model of a church in his left. He converted to Catholicism and, as king of France (1589–1610), issued the Edict of Nantes (1598), a decree promoting religious toleration directed specifically toward the acceptance of French Protestants. Each of the figures represented in the stained-glass window contributes to Eugénie's desire to have the sacred space focus on French history and figures whose faith in Christianity has been forged through personal experiences. At the same time, the iconography clearly expresses tolerance for religious minorities, which relates to Eugénie's own position as a Catholic in England, where she was generally accepted for her beliefs. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

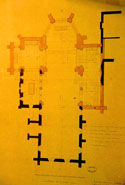

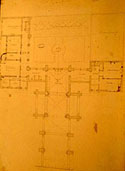

| When the Prince Imperial was killed on 1 June 1879 during a reconnaissance mission with British soldiers fighting Zulus in South Africa, Eugénie decided to expand the mausoleum. As a temporary step, Eugénie ordered that the Prince Imperial's body be entombed in the chapel dedicated to St. Joseph, to the right of the nave and directly across from his father's burial place. An exterior door was cut into the west wall of the chapel to provide Eugénie with private access (fig. 6). But Eugénie desired a more permanent double-tomb structure that would require a reconfiguration of Napoleon's funerary chapel. As early as 24 July, Destailleur presented a plan to Eugénie that shortened Napoleon's chapel on the east end and enlarged it on the west in order to accommodate both Louis's sarcophagus as well as an altar in a domed, hexagonal space. On the southern side of the church Eugénie planned to add a larger chapel dedicated to the Holy Sacrament (fig. 7). On 9 November, Destailleur presented two possibilities to fulfill Eugénie's vision to create an apse for the church that would lead directly to the joint memorial spaces of her husband and son (fig. 8, fig. 9). A rendering from 10 November and a related drawing indicate how the new apse would be flanked by an altar for Eugénie's private use and an effigy of her son Louis being guided to heaven by an angel (fig. 10, fig. 11). As the months passed, Eugénie's vision of the memorial grew more elaborate. A plan from 31 July 1880 repositioned Louis's sarcophagus below an august dome (fig. 12). The most ambitious alternative, dated the same day, shows how Eugénie planned to turn the parish church into a monastic church. This version included two chapels on either side of the church's nave, as well as living quarters, a refectory, a cloister, and gardens for monks who would be charged with attending to the daily rites for the deceased (fig. 13). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The magnitude of Eugénie's plans demonstrate that she was fully committed to staying in Chislehurst and living at Camden Place where she had spent her last years with both men. As early as August 1879, however, Monsignor Goddard feared trouble would flow from the various schemes and wrote to Bishop Danell in the hopes of soliciting his assistance: "My dear Lord, I saw the Empress yesterday about the proposed new building. I should like very much to talk about it with your Lordship. I anticipate difficulties."7 The "difficulties" were that Eugénie's plans for a more exalted structure had aroused the ire of the church's neighbors. Eugénie was well aware of their complaints and, six months prior to the last architectural plans Destailleur developed for Chislehurst, she wrote to Queen Victoria:

Eugénie did not, however, consider abandoning the project. Indeed, a pilgrimage to South Africa, where she visited the precise location where Prince Louis died at Itelezi, as well as a stop, on her return voyage, at Saint Helena where Napoleon I had been exiled, only served to reconfirm her sense of duty to her family's memory. After returning to England she continued to discuss possibilities for Chislehurst with Destailleur while also beginning the search for suitable land elsewhere. The neighbors of St. Mary's did not alter their resolve and Eugénie's relationship with the church officials also deteriorated. This was due in part to Monsignor Goddard's unrealistic expectations about the financial support St. Mary's and his related projects could expect from Eugénie, which she chose not to fulfill.9 Furthermore, the growing fame of the small church with its two illustrious residents caused an administrative ordeal for Goddard. He lamented: "We have every Sunday a crowd of reactionists [sic], French and English, who pretend to think it a great hardship because they cannot turn our Church into a peep show on that day as well as every other in the week."10 Goddard also drafted four new regulations for the church that he sent to Bishop Danell for approval:

Eugénie had lost control over the management of, and her privileged access to, the space she had commissioned Destailleur to create. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Monsignor Goddard's respectful treatment of Eugénie also diminished. Goddard had enjoyed a strong friendship with the Prince Imperial and independently erected an effigy of him in St. Mary's with the inscription: "This monument is erected by his faithful servant and friend The Rt Revd MgR Goddard Rector of this Parish."12 Goddard had also tired of Eugénie's continual state of mourning and even before she left for South Africa he expressed his intolerance in a letter to Bishop Danell:

Clearly Eugénie did not have the necessary support from the local community to pursue her project. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In October 1880, Eugénie found the much-needed solution and bought a mansion on 257 acres of property at Farnborough, 32 miles (51 kilometers) southwest of London. It offered her the space and privacy she cherished, and the freedom required to undertake the commemorative monument she envisioned.14 Again, Eugénie called on Destailleur to construct two buildings, a chapel-mausoleum and a monastery, which together she called St. Michael's Abbey. Contrary to the accepted view, Eugénie was very active in the decisions concerning the construction of the abbey, just as she had been at Chislehurst. Her involvement is evident through two sources: the day-to-day accounts kept by the Clerk of the Works, still preserved at St. Michael's, and the plans for the buildings and interior decorative schemes.15 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

From the start of the Farnborough church and monastery project, Eugénie showed herself to be a meticulous and deliberate patron, in charge of every aspect of planning and construction. She sent Queen Victoria a map of the land she had bought and wrote: "I think that if my dear child would have been able to see the site, he would have liked it. It's near the camp where he passed a period of time he liked to remember." After this reference to the army base at Aldershot where the prince trained before joining the British military, Eugénie continued, "I have marked in pencil the place where I propose to put the mausoleum."16 Two weeks later, she wrote again to Queen Victoria: "The architect came yesterday; he is enchanted by the property and I think he will do as I would like and make a mausoleum which is not sad."17 Construction on the chapel-mausoleum began on 26 April 1883 and continued until 1888, thus overlapping with the building of the monastery, which was constructed in 1886 and 1887 (fig. 14, fig. 15). For the new chapel-mausoleum and the home for the monks who would pray daily for the deceased, Eugénie selected elements from Destailleur's final designs for Chislehurst. At Farnborough, however, she was free to pursue her desire to build a monument worthy of her husband's political achievements and the distinguished lineage of father and son. The only restriction would be her finances. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The stylistic elements of the church, the late flamboyant Gothic design of the chapel raised above a Romanesque crypt, have already been thoroughly studied (fig.16).18 Potential sources for the plans and architectural details of the church and priory have also been noted elsewhere, as has the church's evocation of the funerary traditions of ancien régime France. Aspects of the building were certainly derived from the Lady Chapel of the church of Nôtre-Dame-des-Marais at La Ferté-Bernard and the crypt of the cathedral at Bourges, the latter in a much reduced and almost unrecognizable form. However, the connection of St. Michael's with the cathedral at Tours, which does not have such a prominent dome, is a less convincing comparison.19 To date, the architect Destailleur has been regarded as the most significant decision-maker, however, the following evidence reveals Eugénie's agency in the abbey's creation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A patron such as Eugénie developed mediated relationships with her employees and thus less conventional clues need to be considered to elucidate her precise role. The empress visited the construction site at St. Michael's regularly, however, the records of the Clerk of the Works are, for the most part, registers of expenses rather than an account of decisions made regarding design. Likewise, Eugénie's correspondence offers little guidance, since she was not in the habit of writing to her architect directly. Nor is there any record that she transmitted her specific requests for adjustments to the church and priory directly to the builders. But this does not mean that she was uninvolved. Her secretary Franceschini Pietri acted as an intermediary between Eugénie and the workers, and in the numerous instances where the Clerk of the Works' Diary for New Chapel indicates "Mr. Pietri gave orders"—for example, to approve the bull's eye design and glazing of the nave windows, to accept the contract for stained-glass windows in the sanctuary, or to begin building on the priory—Pietri did not act autonomously but rather with the authority given to him by Eugénie to transmit her instructions (fig. 17). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eugénie's own determination is most readily apparent in the plans, those both intended and realized, for the architecture and interior decoration. Her aspirations for a domed space at Chislehurst were transported to Farnborough and rendered even more grandly. She approved the design of a double-dome that Destailleur submitted on 4 August 1881, a scheme that expanded on her preferred plan for Chislehurst (fig. 18 & fig. 12). The origin of the idea for St. Michael's dome stems from a long tradition of mausoleum design and may also have flowed from a desire to emulate the dome of Les Invalides, under which Napoleon I had been re-interred in 1840. Furthermore, Eugénie had earlier commissioned Eugène Viollet-le-Duc to design a domed mausoleum for her sister Paca, the Duchess of Alba, in 1867; after studying various designs, she chose a presentation drawing, but the building was never constructed (fig. 19, fig. 20). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

With the church at Farnborough, Eugénie finally succeeded, after a decade of failed attempts, in having a domed mausoleum built for a loved one. Her conception of imperial iconography was reinforced by sculpted heraldry in the dome: Napoleon's coat of arms is placed in each of the four raised squinches and her own heraldic emblem appears in the nave arch (fig. 21, fig. 22).20 The painting of the dome interior was not completed as she had hoped, but both she and Destailleur kept a copy of the approved plan, a decorative combination of imperial gold and blue (fig. 23). Eugénie entrusted the interior decoration to a team of French painters with whom she had considerable experience; during the Second Empire, J. Lachaise and L. Gourdet had repainted the Salle des Cerfs at Fontainebleau and had also worked on Eugénie's private hôtel in Paris on rue de l'Elysée.21 The design they proposed for the transepts was completed as intended below the windows, but other iconographic details were never realized (fig. 24, fig. 25). Again, both patron and architect kept copies of the plans Eugénie had considered for the painting of the side chapel and nave ceiling. A flap on the drawing presenting alternative color schemes for the decorative patterning on the wall and vault shows that the choices were between blue and green or rose and red (fig. 26, fig. 27). Such evidence indicates Eugénie's principal role as decision-maker. Since none of this painting was completed, however, we do not know which project she approved. Eugénie had also thought to paint the sacristy door and to put a sculpted statue of St. Michael and the dragon above it, reinforcing the chapel's identification with the patron saint of France (fig. 28). The statue was placed instead more prominently over the altar, thus emphasizing Eugénie's final decision to dedicate the entire complex, not just the chapel, to St. Michael. Unlike most of the decorative wall painting, all of the elaborate patterning of the wood floors of the chapel and crypt were completed to Eugénie's specifications (fig. 29, fig. 30). And at great additional expense, Italian workers were engaged in the fall of 1884 to lay the stone floor of the chapel, which was designed after the tessellated pavement in Les Invalides.22 While only some aspects of the interior decoration were executed, it is clear that Eugénie's aesthetic choices were guided by politics. She intended to use colors and symbols that reinforced French nationalism and Bonapartism within the sacred space of the chapel-mausoleum. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Over time, Eugénie lost some control over the project as her relations with the abbey's monks deteriorated. This began in 1896, three years after the death of Destailleur, when Prior Cabrol, the principal religious leader at the abbey, began discussions with a new architect, Benedict Williamson, about enlarging the priory and church.23 While Eugénie was supportive of Williamson's grand plans to add two bays to the nave, a spire, a bell tower, and two sacristies, his proposals also directed her financial resources away from her plans for the painted interior designs (fig. 31). Ultimately, Williamson altered only the priory but not the church (see far right, fig. 14). Destailleur had designed the priory after the Louis XII wing at the Château of Blois and Williamson added an incongruous addition that he designed in the style of the neo-Romanesque architecture of the abbey of Solesmes (fig. 32). The addition at St. Michael's was completed at the same time that a wing was also added at Solesmes and, lacking Destailleur's skills at architectural pastiche, Williamson simply replicated Solesmes, the place of origin of the Benedictine monks who had newly arrived at Farnborough in 1895. Eugénie was so displeased with the addition that she withheld further financial support for the projects. After her death, a member of the priory wrote in amazement: "How could the abbot and chapter have opted for buildings which could never be finished or paid for, and which so upset Her Majesty?"24 Indeed, the relationship remained tense during the final twenty years of her life. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| If Eugénie had not taken on this project, there would be no comparable monument commemorating the Second Empire. The only other family member who was in a financial position to pursue such an undertaking was Prince Jérôme Napoléon, Napoleon III's cousin. But Jérôme was notoriously jealous and had always felt threatened by Eugénie, particularly after she gave birth to an heir, dashing his hopes of ever assuming the French throne. It was Eugénie, a Spaniard by birth, who embraced the country and family into which she married and who funded the construction of this monument.25 Despite the conflicts and unfulfilled plans, Eugénie's persistence and vision were such that she was able to create a grand structure that celebrates the Second Empire. Due to Napoleon III's notorious extramarital affairs, her marriage had been, at times, less happy than that of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. But their final three years together in England reunited the couple and consolidated Eugénie's dedication to the memory of her husband and his eighteen-year reign as emperor of France. At Farnborough, Eugénie's contributions to St. Michael's Abbey remained strongly rooted in French visual culture. To this day, the mausoleum to her husband and son testifies to her strategic role as a visionary architectural patron in the creation of the sole major monument commemorating the Second Empire. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I presented an earlier form of this paper, "Empress Eugénie and the Napoleonic Mausoleum at Farnborough," in the session Women as keepers of historical memory at the College Art Association conference in Philadelphia in February 2002. I am grateful to Pamela H. Simpson and Cynthia J. Mills for their comments on my oral report. I would also like to thank Hayden B.J. Maginnis and William H.C. Smith for their comments on an earlier draft of this essay. Research for this project was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. 1. In France, there is a small monument dedicated to the Prince Imperial located behind the château at Malmaison. This was designed by Hippolyte Destailleur in 1894 and houses a copy of Carpeaux's statue The Prince Imperial and his dog Nero (1867). 2. In his important study of Farnborough Abbey, Anthony Geraghty noted: "It is not known how the Empress came to select Destailleur as her architect...it may well have been they [the Duke and Duchess of Mouchy] who brought Destailleur to the attention of the Empress." Anthony Geraghty "Farnborough Abbey: Bonapartism, Legitimism and the Gothic," Master's Report, Courtauld Institute of Art, 1994, p.4. Ferdinand de Rothschild remarked in a letter he wrote while convalescing at Chislehurst: "The Empress Eugénie has purchased some land from Strode the owner of Camden Place, and my Frenchman is going to build her a house on it." 7 August 1880. Archives, Waddesdon Manor. I thank Philippa Glanville, Director, for making this material available.

4. Monsignor Goddard wrote to Bishop Danell on 28 May 1873: "My dear Lord, on Saturday June 7th at 1-30 the Empress and Prince Imperial will lay the foundation stone of the new chapel. If your Lordship is able, it would be a great satisfaction and happiness to us if you would kindly preside at this simple ceremony. If your Lordship is able to come down on Saturday next perhaps you will be able to drive down to see what has been done." It is not known if Bishop Danell attended the ceremony. Chislehurst Papers, Archive of the Archdiocese of Southwark, London. 5. Monsignor Goddard wrote to Bishop Danell on 21 December 1873: "My dear Lord, As at present arranged, subject, of course, to your Lordship's sanction, the late Emperor is to be transferred to his new resting place on the anniversary of his death Jan 9th between 8 and 9 in the morning. The te deum requiem mass is to be sung between 11 and 12. Will your Lordship come and officiate at the mass? I shall be extremely grateful if you will. The 9th is within the octave of the Epiphany, but there will be no difficulty about a solemn mass for the dead, will there?" Chislehurst Papers, Archive of the Archdiocese of Southwark, London. 6. For my in-depth discussion of the significance of Saint Helena see: "Empress Eugénie and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre," Source vol.21, n.1, Fall 2001, 33-37. 7. Letter from Monsignor Goddard to Bishop Danell 21 August 1879. Chislehurst Papers, Archive of the Archdiocese of Southwark, London. 8. RA VIC/Z 136/33, 24 January 1880. Royal Archives, Windsor Castle. I thank Miss Pamela Clark, Registrar, for her assistance with my work at the Royal Archives. Materials from the Royal Archives are included with the permission of Her Majesty The Queen. It is not accurate, as has previously been stated, that Eugénie was prevented from completing this addition solely because of the "Protestant zeal of a local landowner." See Anthony Geraghty "St. Michael's Abbey, Farnborough: A Gothic mausoleum for Napoleon III," Apollo vol.143 no.407 (January 1996): 9-12 (9). 9. Monsignor Goddard was specifically concerned with financial support for a school which he built across the road from the church. He wrote to Bishop Danell 29 September 1877: "My dear Lord, Telegram just received. I am most grateful to your Lordship. When I began the school I had every reason to hope that the Imperial family would not only be here, but would subscribe handsomely. So far from that they have been absent for more than a year, making me no allowance whatever and not subscribing a penny to the building." Chislehurst Papers, Archives of the Archdiocese of Southwark, London. 10. Letter from Monsignor Goddard to D. Cullington, 9 July 1879. Chislehurst Papers, Archive of the Archdiocese of Southwark, London. 11. Letter from Monsignor Goddard to Bishop Danell, 2 July 1879. Chislehurst Papers, Archive of the Archdiocese of Southwark, London. 12. The artist and date of this work were not recorded. 13. Letter from Monsignor Goddard to Bishop Danell, 25 March 1880. Chislehurst Papers, Archive of the Archdiocese of Southwark, London. 14. The property first went up for auction 17 June 1880. The auction catalogue described the property as: "delightfully situate[d] on Farnborough Hill, commanding picturesque views on all sides…surrounded by its own beautiful flower gardens, pleasure grounds, ornamental Park and woodlands" and a copy of the auction catalogue remains with Destailleur's papers in the National Archives, Paris, 536AP66. For the history of Farnborough Hill and Eugénie see Dorothy Mostyn The Story of a House (Farnborough Hill, 1980) and William H.C. Smith "The Empress Eugénie and Farnborough," Hampshire Papers (Hampshire County Council, 2001) William H.C. Smith has also written the most important recent biographical study of Eugénie: Eugénie, impératrice des Français (Paris, 1998). 15. Diary for New Chapel. 4 vols. Archives, St. Michael's Abbey. I am very appreciative of Prior Dom Cuthbert Brogan's (OSB) help and guidance during my visits to Farnborough. 16. RA VIC/Z 137/7, 21 September 1880. 17. RA VIC/Z 137/10, 7 October 1880. 18. See Geraghty 1994. 19. These quotations were first cited by Anthony Geraghty, see fn.1, p.8-14, 20-21. The exterior of the chapel has recently been restored; for a complete account see Michael Carden "St. Michael's Abbey, Farnborough," Church Building 63 (May-June 2000): 30-33. 20. Geraghty noted that such use of heraldry adds a Spanish flavor to the crossing and can be compared with architectural devices at Santiago de Compostela and San Juan de los Reyes in Toledo (Geraghty 1994, p.11). Further research may clarify Eugénie's role in developing these parallels. 21. Several designs by Lachaise and Gourdet for Fontainebleau, and the Hôtel, rue de l'Elysée, are in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 22. The floor work is documented in Diary for New Chapel, vol.4. No evidence supports the anecdote that Eugénie's selections for the floor evoked Les Invalides only by chance; this is also a misinterpretation of the extant evidence of her close management of the project. The anecdote is repeated by Geraghty p.18-19, as noted previously in David Higham Chapters of the History of Saint Michael's Abbey, Farnborough, MS in Farnborough Abbey Archive, n.d., p.7. 23. Four of Williamson's architectural drawings remain in the archive of St. Michael's Abbey. Williamson drew the most developed of these drawings on the back of a letter to Abbot Cabrol dated 27 May 1896. Williamson trained as an architect with the firm Newman & Jacques, Stratford, London E. and practiced architecture from 1896-1906. For a discussion of his life and architectural projects see Ulla Sander Olsen "The Revival of the Birgittine Monks in the Twentieth Century: Various Attempts," in Analecta Cartusiana Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik un Amerikanistik, 2000, pp.37-73. Prior Cabrol was raised to Dom Cabrol after the priory was elevated to the status of an Abbey in 1903. 24.Quote of Dom l'Huillier in "Chapters in the History of Saint Michael's Abbey," Laudetur (May 2001), p.21. 25. Funding for the project came largely from properties she owned in Spain. For a discussion of some of these properties see Pierre Ponsot "Economie traditionelle, techniciens étrangers, et poussée capitaliste dans les campagnes espagnoles au XIXe siècle. L'exemple de deux domaines d'Eugénie de Montijo," in Études sur le dix-neuvième siècle espagnol (Cordoba, 1981) pages 105-136. I thank William H.C. Smith for sharing a copy of this article. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||