From Center to Periphery: International Collaboration in Mid-Nineteenth Century Rome and the Artistic Milieu for a Silver Commission for Malta

by Mark SagonaMark Sagona is head of the Department of Art and Art History, Faculty of Arts, University of Malta, where he lectures in art history and fine arts. His research has focused primarily on the nineteenth century, with a particular interest in the decorative arts in Malta in their international context. He has published widely on this subject, including in several issues of the Journal of the Decorative Arts Society, 1850 to the Present (2015, 2021) and in Revivals (2022). His recent publications include International Perspectives on the Decorative Arts: Nineteenth-Century Malta (Midsea Books, 2021) and Identity of an Island – Gozo: Art between Past and Present (Teatru Astra and Midsea Books, 2022). He has recently participated in international conferences convened by the Universita’ degli Studi di Napoli Federico II (June 2021), the Universita’ degli Studi di Palermo (April 2023), and the International Committee for Museums and Collections of Decorative Arts and Design (ICDAD) in Lisbon (October 2023). Sagona is also a practicing visual artist and curator.

Email the author: mark.sagona[at]um.edu.mt

Citation: Mark Sagona, “From Center to Periphery: International Collaboration in Mid-Nineteenth Century Rome and the Artistic Milieu for a Silver Commission for Malta,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.1.5.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

On Wednesday, April 27, 1853, the Giornale di Roma carried a short article regarding the commission of four silver altar statues of the Evangelists—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—for the Parish Church of St. Philip of Agira in Żebbuġ on the island of Malta.[1] Intended for the first gradine of the high altar (fig. 1),[2] the sculptures were a gift of the wealthy Żebbuġ priest Don Michelangelo Raimondo Calleja (fig. 2), a generous benefactor of his parish church,[3] whose coat of arms appears on each of the supporting gilt dadoes. The Evangelists (fig. 3) were produced in the workshop of the artistically significant but little-studied Roman silversmith Vincenzo Belli the Younger (active 1828–59), who hailed from an important family of silversmiths.[4] For the completion of the sculptures, Belli was paid the considerable sum of 5,500 scudi.[5] This commission was first mentioned in an article in the Maltese newspaper L’Ordine in April 1852.[6] A subsequent article in the same paper mentioned, much to the delight of the Maltese, that it had even drawn the attention of Pope Pius IX (r. 1846–78).[7]

The Evangelists commission epitomizes Malta’s strong artistic ties to Rome throughout most of the nineteenth century. The island nation’s fascination with Rome went back to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when the ruling Knights of Saint John sought to acquire art of the highest quality from the Eternal City, commissioning significant works from the hands of sculptors, silversmiths, and bronze founders such as Ciro Ferri (1634–89), Urbano Bartalesi (1641–1726), Girolamo Lucenti (ca. 1625–98), Giuseppe Mazzuoli the Elder (1644–1725), Massimiliano Soldani (1656–1740), and Antonio Arrighi (active 1733–76), among others, to adorn their Conventual Church in Valletta.[8] The important Arrighi commission of a magnificent set of fifteen silver altar statues for the high altar of the Conventual Church in the early 1740s,[9] now preserved at the Mdina Cathedral Museum in Malta, can be considered as an antecedent to the Belli Evangelists.

Though the sociopolitical climate of Malta changed drastically in the nineteenth century, especially after the island had become a British protectorate in 1800 and a full-fledged Crown Colony in 1813, the Italian connections remained strong, and among the numerous foreign influences visible in nineteenth-century Maltese art, which included British, French, German, and North African, Roman art continued to be paramount. This happened in part because of the powerful presence in Malta of the Roman Catholic Church, which dominated all rungs of society.[10] It caused many Maltese churches to commission artworks from artists in Rome, particularly those who had made a name in the Roman ecclesiastical world. Paradoxically, however, it was the British who further encouraged the artistic links with Rome by sending a number of promising Maltese students to train at the Accademia di San Luca in the second decade of the nineteenth century, through the so-called Maitland Bursaries,[11] established during the governorship of Thomas Maitland (1760–1824; governor from 1813). Henceforth and throughout the nineteenth century, the majority of Maltese artists of significance were trained in Rome, further strengthening Malta’s artistic ties with the Eternal City.[12]

Though the Żebbuġ Evangelists, commissioned by a Maltese church from a Roman silversmith, reflected the standard nineteenth-century ecclesiastic-patronage practice on the island, the work is unusual for the international context within which it was generated. As will be shown in this article, the Roman silversmith Belli fashioned his Evangelists after four models, presumably in plaster, by the sculptor Pietro Galli (1804–77), a student, and later assistant, of the famous Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (ca. 1770–1844). Galli, in turn, based his models on four drawings by the German Nazarene painter Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789–1869) or on the frescoes produced from his drawings by Overbeck’s student Alexander Maximilian Seitz (1811–88) in the chapel of the Casino Torlonia in the town of Castel Gandolfo. The Żebbuġ Evangelists thus show the receptiveness on the periphery of Europe not only to art produced in one of the continent’s artistic centers—Rome—but also to one of the major characteristics of Roman art of the period, namely, its international character. This openness to international collaboration that led to the production of the Evangelists, even in a small Maltese town like Żebbuġ, may be seen as a reflection of the culture of the island itself, which in its long history had been ruled by Phoenicians, Romans, Arabs, Normans, Angevins, the Knights of the Order of Saint John, the French, and the British. In such a culture, marked by amalgamation and hybridity, the complex international production history of the Żebbuġ Evangelists made for their ready reception.

The Commission of the Żebbuġ Evangelists

Most of what we know about the genesis of the Żebbuġ Evangelists comes from the Giornale di Roma article mentioned above. It contains a sentence that appears to provide important insights into the evolution of the silver altar figures:

With wise advice, Mr. Belli wanted them [the Żebbuġ Evangelists] to portray the concept, and the purity of the Evangelists painted by the brush of the distinguished Cav. Overbeck in the chapel of the Casino Torlonia in Castel Gandolfo; in which he was so well supported by the very able sculptor Signor Galli, who had supplied him with the plastic models, that in reality nothing could be more in conformity with the sound principles of art.[13]

“Signor Galli” was, no doubt, the sculptor Galli,[14] and his “plastic” (i.e., three-dimensional) models, according to the article, were based on the four Evangelists painted by Overbeck in the chapel of the Casino Torlonia. The author of the article apparently did not know that, in reality, the four Evangelists in the Torlonia chapel, as well as a series of figures of the apostles, were drawn by Overbeck but painted by his follower and collaborator, the German painter Alexander Maximilian Seitz.[15]

Although the sentence in the Giornale di Roma suggests only an indirect relation between Belli and Overbeck, it appears that the involvement of Overbeck was more direct than what was implied. The Żebbuġ priest Salvatore Ciappara, in his book of 1882 on the history of his Parish Church of St. Philip of Agira, speaks of a letter sent by Belli from Rome to his compatriot and fellow priest Filippo Grima.[16] Quoting the letter, Ciappara states that Overbeck had visited Belli’s studio to see the Saint Mark and Saint John statues and had enthusiastically approved of his work.[17] This clearly shows that Overbeck was directly following the development of the work and perhaps was even giving Belli personal advice. Indeed, though the commission for the Żebbuġ Evangelists had clearly gone to Belli, it may be possible to see the outcome as one that was conceived and carried out in phases, supervised by Overbeck, Galli, and Belli. In each phase, the four figures were translated into a new medium—from drawing to painting, from painting to sculpture, and from sculpture to decorative art.

The Żebbuġ Evangelists also are significant for heralding another crucial moment in the island’s artistic history. In 1860, Luigi Fontana (1827–1908), Tommaso Minardi’s (1787–1871) closest pupil and follower, was entrusted with the production of Saint Philip of Agira, a silver processional statue for the same Żebbuġ parish church (fig. 4), a work which was to crown and seal the Malta-Rome connection.[18] Undoubtedly, the success of the Evangelists spurred the Żebbuġ parishioners to strengthen their aspiration for a life-size effigy of their patron saint. It is fascinating to note that the Saint Philip of Agira project was supervised by Overbeck, who sent a report to Malta in January 1863.[19] The statue finally arrived in Malta, accompanied by its artist, in July 1863. Indeed, Belli would have been a strong candidate for the silver execution of the statue of Saint Philip, but his death in 1859 robbed him of this prospect. The repeated involvement of Overbeck with commissions coming from the Parish Church of St. Philip of Agira might indicate that someone in the parish had direct access to the artist.

Johann Friedrich Overbeck

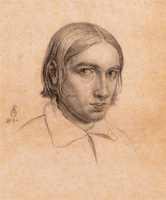

Though the precise role of Overbeck in the creation of the Żebbuġ Evangelists is unclear, his connection to the works is undeniable. It is not known how he became connected with the commission of the Evangelists, but by the 1850s, his name was well-known in artistic and cultural circles in Malta, and together with his contemporary Minardi, he had become one of the luminaries for Maltese artists to follow.[20] Overbeck’s relationship with Malta was established through Giuseppe Hyzler (1787–1858), a dominant artistic figure on the island in the first half of the century. Hyzler, belonging to a Maltese family of German extraction, was the first among several promising artists of the early nineteenth century to travel to Rome under Governor Maitland, establishing close contacts with the Lukasbrüder or, as they came to be more popularly known, the Nazarenes. This group of German painters had established themselves in the Eternal City in 1810 under the leadership of Overbeck and Franz Pforr (1788–1812).[21] Following the latter’s tragic early death, it was Overbeck who came to epitomize the movement’s ideology, and Hyzler formed an important and enduring relationship with him, which continued even after his return to Malta. A wonderful Self-Portrait in graphite by the young Overbeck, signed and dated 1824 (fig. 5), in the Maltese National Collection at MUŻA, arrived in Malta most probably through Hyzler.

Back in Malta in 1822,[22] Hyzler sought to establish Nazarene ideals with an almost missionary zeal, gradually purging the islands from the outmoded theatricality of the baroque.[23] Hyzler was thus largely responsible for the shift in Maltese artistic taste from Baroque to Renaissance Revival between the 1830s and the 1860s. Overbeck’s imprint can especially be witnessed in the works created by Hyzler in the 1830s, such as the altarpiece of the Virgin of the Rosary at the Valletta Dominican Church (an extraordinary line drawing which may be seen at MUŻA) and the altarpiece that comes closest to the purity and chastity of the German master: the Virgin of Manresa Appearing to Saint Ignatius of Loyola at the Jesuit Retreat House in Victoria, Gozo, Malta (fig. 6). These two works, like the works of Overbeck, are inspired by Early Renaissance masters like Giovanni Bellini (1430/1436–1516) and Pietro Perugino (1450–1523), perhaps with a hint of Giorgione (1477–1510). Hyzler also surrounded himself with several students who propagated the Nazarene ideals in their works.[24]

Pietro Galli

In September 1853, L’Ordine provided important details about the sculptor who produced the models of the Evangelists. Together with Pietro Tenerani (1798–1869),[25] who was fifteen years his senior and had become the principal sculptor in Rome by mid-century, Galli was one of the favorite students of Thorvaldsen, who had made Rome his home since 1797 and who was, after Antonio Canova (1757–1822), the best-known neoclassical sculptor in Europe. Like numerous young sculptors of his time, such as Pietro Bienaimé (1781–1857) and his younger brother Luigi (1795–1878), Giovanni Albertoni (1806–87), Ercole Dante (active mid-nineteenth century), and Cesare Benaglia (active mid-nineteenth century), Galli formed part of Thorvaldsen’s well-organized atelier, which catered to an ever-growing number of buyers and allowed for the execution of commissions even during Thorvaldsen’s prolonged absences.[26]

In his short biography of the artist, Galli’s nephew Guido recounts how the master received his artistic education at the Accademia di San Luca and was taken under the wings of Thorvaldsen after the latter had admired a bas-relief by the young artist in the early 1820s. Henceforth Galli collaborated with Thorvaldsen for twenty-three years and in 1838 was placed in charge of his atelier, completing several of the master’s unfinished works.[27] Like Thorvaldsen’s older student Tenerani, Galli was thoroughly familiar with his teacher’s neoclassical style and his works generally share its character, though at times they show more Renaissance characteristics.

Galli’s participation in the commission of the Evangelists coincides with the years of his increased patronage by Pius IX. As an appointed sculptor to the Fabbrica di San Pietro (the institution in charge of the maintenance and conservation of St. Peter’s) from 1850,[28] Galli’s works in marble for St. Peter’s Basilica include the colossal statues representing Saint Francesca Romana and Saint Angela Merici. The latter (fig. 7) is signed and dated 1866. Additionally, Galli is the author of the sensitively carved bas-relief of Pius IX Proclaiming the Dogma of the Immaculate Conception on the base of the Immaculate Conception column in the Piazza di Spagna. Another significant work, which is treated at some length in Galli’s biography, is the holy-water basin in the right transept of the Basilica of San Paolo fuori le Mura (St. Paul Outside the Walls), signed and dated 1860 (fig. 8). In a considerably original approach, the work is fashioned in the form of an elegantly decorated baluster carrying a shallow basin surmounted by the coat of arms of Pius IX. It includes the figures of a Renaissance-inspired barefooted child, who reaches up for holy water, setting to flight a kneeling devil, hiding his face in shame. Furthermore, some of the wooden reliefs in the richly carved choir stalls in the Church of San Crisogono in Trastevere are based on models by Galli.[29]

Information on Galli’s models for the Malta Evangelists, which are not known to be extant today, is extremely scant. L’Ordine talks about Galli and his works rather than about the actual models. The likelihood that they were produced in plaster is particularly high, because Galli would have learned this method from his master.[30] It is not known either who commissioned Galli for the production of the models. Most likely the initiative for this would have come either from Overbeck himself or else from Belli, who would have known perfectly the requirements for such a commission. Due to the lack of correspondence, documentation, and the models themselves, the dynamics of the commissioning and execution of the models remains very hypothetical.

Vincenzo Belli the Younger

The central player in the Evangelists commission is Belli, the silversmith (or, as the Giornale di Roma calls him, “metal sculptor”) responsible for their manufacture. Belli, a pivotal figure for the relationship between Malta and Rome in the middle years of the century, received his license as master goldsmith on August 31, 1828, soon after the death of his father Pietro in July 1828.[31] Vincenzo took over his father’s workshop at 63 and 64, via del Teatro Valle, where he collaborated with his brother Antonio (active mid-nineteenth century),[32] subsequently moving premises to 86, Piazza Borghese. Belli was elected goldsmiths’ console, or value regulator of precious metals, in Rome in 1835 and 1843. His works usually carry his distinct maker’s mark VIIB (Vincenzo Belli II).[33] This mark features in various places on the Malta Evangelists.

Belli the Younger came from a long dynasty of gold- and silversmiths. Members of the Belli family included Vincenzo Belli the Elder (1710–87), who moved from Turin to Rome around 1740,[34] and his sons Gioacchino Belli (active 1788–1822)[35] and Pietro Belli (active 1780–1828),[36] Vincenzo the Younger’s father. Designs by Pietro are extant at the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York,[37] while a chalice in the Sacrario Apostolico (Apostolic Shrine) of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican by Gioacchino epitomizes the family’s elegant and sophisticated style.[38] Belli the Younger came to push the important tradition of Roman neoclassical silver into the second half of the nineteenth century.

Belli died on November 12, 1859. A brief announcement appeared in L’Ordine on November 25, 1859,[39] but the same newspaper carried a detailed obituary on December 23 of that year, quoting the December 3, 1859, issue of the Giornale di Roma.[40] It hailed Belli as a sculptor whose work deserved comparison with that of Benvenuto Cellini (1500–71) and Giambologna (1529–1608). The obituary is of special interest since it refers to a number of works by the artist. These include the gilt-bronze decoration of the transeptal altars of the Basilica of San Paolo fuori le Mura in Rome (fig. 9) together with the papal throne in the apse of the same church (fig. 10); the gilt-bronze altar for the Benedictine Monastery of San Nicolò l’Arena at Catania; three silver lamps for Orvieto Cathedral; a monstrance (the liturgical objet d’art used for the adoration of the Eucharist) for a church in Dublin, Ireland; and a life-size silver crucifix for the Buonfratelli Church at Pisa, after a model by Tenerani. The gilt-bronze decoration on the spectacular transeptal altars at San Paolo fuori le Mura in Rome mentioned above, consecrated by Pope Pius IX in 1854, is typical of the master. The decoration and the two standing angels on either side of the altar create a striking contrast with the malachite which makes up the altar’s body. The ornamental decoration is produced with great sensitivity and an intimate familiarity with the classical repertoire. The final effect is one of a sober sophistication and dignified elegance, comparable to the artistic ethos of the Malta Evangelists.[41]

Belli’s obituary in L’Ordine also mentions several works he produced for Maltese churches, including the Żebbuġ Evangelists, two antependia (removable screens, generally of a decorative nature, made of silver, wood, or cloth and placed in front of the altar table) for St. Paul’s Shipwreck Church in Valletta, and the exposition throne for the Valletta Carmelites. Belli had made an effort to establish Malta as a notable outlet for his fine silver production. The reason for his ten-month stay on the island, between January and November 1843,[42] may have been to tap potential clients and possible commissions. Although the dynamics of Belli’s first links with Malta are still nebulous, it is likely that his earliest patron in Malta was St. Paul’s Shipwreck Church in Valletta, which boasts the largest concentration of works by Belli on the island. The church owns what may be Belli’s first work produced for Malta, perhaps even during his 1842 stay, a parcel-gilt reliquary for the arm of St. Paul, the island’s most important relic (figs. 11a, 11b). The reliquary, which carries Belli’s maker’s marks,[43] is devised in the form of an open right lower arm, which rises from a rectangular shallow pedestal, typical of Roman Neoclassicism. It is admirable for its beautiful modeling and refined tooling.

Some ten years later, in the early 1850s, the confraternities of Saint Homobonus (tailors) and Saints Crispin and Crispinian (cobblers) acquired a number of important works from the master for the same church. The first was a silver antependium for the altar of Saint Homobonus (fig. 12), which arrived in Malta in 1852, accompanied by the artist himself.[44] The artist’s presence in Malta is proven by a receipt dated March 19, 1852,[45] written in Malta in the artist’s own handwriting. Other commissions followed, including modifications to the confraternity’s already existing reliquary, a pendant lamp, and a similar pendant lamp and antependium for the confraternity of cobblers,[46] delivered by February 1853.[47] Two years later, in 1855, Belli delivered a full set of twelve candlesticks with their cross for the altar of the Confraternity of the Virgin of Charity also at St. Paul’s Shipwreck Church.[48] The two antependia at St. Paul’s are among the most remarkable works by Belli and demonstrate the full breadth of his artistic prowess. The Żebbuġ Evangelists commission arrived in the middle of this succession of works, which kept the master extremely busy for the first half of the 1850s.

Belli’s “Maltese” oeuvre has been significantly amplified through recent documentary, technical, and comparative research. Rather unexpected are the commissions for the Cathedral of the Assumption in Victoria, on the island of Gozo, also part of the Maltese archipelago, which includes a silver frame with gilt-metal borders for the embroidered antependium of the high altar, dating to 1854; and a chalice and a remarkable silver missal cover (fig. 13), donated separately in 1853 and 1855.[49] Additional works have been identified in other churches in Valletta, Cottonera, and Rabat. These comprise a set of three altar cards at the Cospicua parish church, a set of four processional lanterns belonging to the Confraternity of the Blessed Sacrament at Senglea parish church, a set of six baldachin staffs at St. Paul’s parish church in Rabat, a silver frame for the effigy of the Virgin of Doctrine on one of the side altars at the Valletta Dominican church, and a chalice in the collection of the Church of St. Francis of Assisi in Rabat (fig. 14). All the works carry Belli’s maker’s marks and his distinct classical, ornamental vocabulary.

Belli’s last fully documented work for Malta dates to 1858 and was commissioned by the Confraternity of the Virgin of Mount Carmel in the Carmelite Church in Valletta (fig. 15). This is a splendid exposition throne for use during the Quaranta Ore (Forty Hours) devotion, which was reported in the local[50] and the Roman press.[51] The work could be viewed in the artist’s studio, which had, by now, moved to the Piazza Borghese. The press commented on the beauty of the work, the variety of decoration and ornament, the Eucharistic symbols, and the striking effect of a large raggiera, or sunburst, of gilt metal which acted as a backdrop. The Giornale di Roma showered Belli with praise, stating that this work outshone his other works for Malta. The throne, in silver with gilt-bronze mounts, has unfortunately not survived in its original form, since it was sadly mutilated and partly refashioned into a tabernacle.[52] It nonetheless impresses for the high level of its execution and the nobility of its design, which is largely classical in inspiration. Payments for the work were settled in three transactions, and the final bill settled almost a year and a half after Belli’s demise, on April 13, 1861.[53]

The Torlonia Connection

The connection between the Torlonia family and the artists in Belli’s network is paramount both to the significance of the commission of the Evangelists and the argument of this paper, because several of the key players involved, directly or indirectly, with the commission hailed from a network of artists who profited from the patronage of the newly established, princely family. Both Overbeck and Galli worked for the powerful Torlonia family, which administered the finances of the Vatican and participated actively in art patronage in nineteenth-century Rome.[54]

The rags-to-riches story of the Torlonia family can be traced to seventeenth-century France. Rising from a modest peasant background in Auvergne, Marino Tourlonias (1725–85) arrived in Rome around 1750 as a servant in the entourage of his master, the abbé Charles Alexandre de Montgon (1690–1770).[55] Subsequently working as a valet for the diplomat Cardinal Acquaviva, Marino transformed himself from servant to merchant, thanks to a small legacy he received from the cardinal. The ambitious and enterprising Marino launched a thriving trade in textiles from Lyon.[56] In 1764 he was registered as a merchant under the Italianized name of Torlonia, and in 1776 he supplemented his trading activity with moneylending.[57] The extensive fortune he succeeded in accumulating served as the basis for the ascent of his son Giovanni Raimondo (1754–1829), who would give up the family’s trading activity in favor of banking, gaining access to the Corpo dei Banchieri di Roma (Bankers’ Association of Rome) in 1779.[58]

In the aftermath of the papacy’s financial crisis of the mid-1790s, resulting from the armistice of Bologna and the Treaty of Tolentino, Giovanni Raimondo Torlonia became the principal banker for the Papal States,[59] attaining, among others, the title of nobility in 1794 from the Holy Roman Empire, and the Dukedom of Bracciano in 1803. In the meantime, he took on important business ventures such as the Tolfa alum quarries and the textile factory of the Papal States in Rome.[60] Significant purchases followed, including a large villa on via Nomentana and a palazzo in Piazza Venezia, the latter sadly demolished in 1903, which was to become the new home of Canova’s famous Hercules and Lichas (1795–1815; Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome).[61]

Art patronage and collecting consolidated the Torlonias’ social emancipation and attainment of nobility. Many of the great artists of the time worked for Prince Giovanni, including the eminent architect Giuseppe Valadier (1762–1839),[62] the painters Vincenzo Camuccini (1771–1844) and Pelagio Palagi (1775–1860), and the sculptors Canova and Thorvaldsen.[63] Giovanni commissioned a colossal group from Thorvaldsen representing Achilles and Pentesiliea—destined to remain at the stage of a bozzetto (a small clay sketch)—as a pendant to Canova’s Hercules and Lichas in the palazzo in Piazza Venezia, which witnessed the employment of the most important artists and craftsmen in the city.[64] Canova produced ten reliefs, now lost, for the ballroom of the villa in via Nomentana.[65] Giovanni’s sons Marino (1796–1865), Carlo (1798–1847), and Alessandro (1800–86) were born into this sphere of wealth and aristocracy.

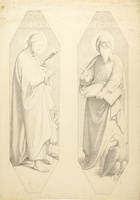

Thorvaldsen’s link with the Torlonias began as a client of their bank. It was only after Giovanni’s demise that his artistic services were sought by the brothers Alessandro and Carlo. From the early 1830s onward, Thorvaldsen and his pupils were in constant Torlonia employment. The patronage of the family was at times so strong that it even eclipsed that of the papacy. The protagonist in promoting the grand commissions for the two Roman residences in via Nomentana and Piazza Venezia was the third-born Alessandro, the heir to the ambition of his father and the new head of the Torlonia bank.[66] His elder brother Carlo focused his efforts on the Villa Carolina at Castel Gandolfo, which he had received as a legacy from his father. The Overbeck frescoes were commissioned for the chapel inside this villa. Described as “a man of great gentleness and poor health,”[67] Carlo directed his wealth to charitable acts, displaying an ascetic and religious sensibility which pushed him away from material gains.[68] Perhaps it was his pious temperament that drew him toward the chaste and spiritual art of Overbeck. Carlo wanted Overbeck to decorate the Castel Gandolfo with frescoes, but the artist was too pressed with commitments to take it on. At the prince’s insistence, however, Overbeck agreed to produce drawings and cartoons of the apostles and the Evangelists, selecting Seitz—a former pupil of Peter von Cornelius (1783–1867)—to execute the commission in fresco. Overbeck scholar Margaret Howitt places the production of the drawings and cartoons between December 1835 and February 1844; the fresco realization purportedly started in September 1843, and for a number of days, Seitz was accompanied by Overbeck himself onsite.[69]

The Torlonia link may explain the intermediary role of Galli in the Evangelists commission. If Belli had contacted Overbeck to ask permission to base the four Evangelists on his drawings, Overbeck may have selected Galli as the sculptor to translate his two-dimensional drawings into three-dimensional sculptures, as both were part of the network of artists working for the Torlonia family. By the early 1850s, Galli had worked on various occasions for the Torlonia family. For example, upon Thorvaldsen’s decision to return to his homeland, he promised Carlo Torlonia that he would design a series of bas-reliefs to decorate the villa at Castel Gandolfo, which would be executed by Galli.[70] Additionally, Galli was responsible for the execution of the monumental marble tympanum on the façade of the same villa from models prepared by Thorvaldsen. Galli’s participation in the commission[71] was the subject of a long, front-page article which appeared in the Roman newspaper Il Tiberino, on Monday, June 1, 1840.[72] Also by Galli were the now-lost stucco reliefs representing scenes from the Iliad adorning the Sala di Diana (Hall of Diana) in the former Torlonia Palace in Rome. These were repeated in the theatre of the villa in via Nomentana.[73]

Galli was also employed on the decoration of the Torlonia Chapel at the Basilica of St. John Lateran, for which Tenerani provided his celebrated marble high relief of the Descent from the Cross in 1846.[74] The four elegant and polished reliefs of the Evangelists in the pendentives beneath the dome, and the several stucco reliefs within the coffers in the vault, are Galli’s work (fig. 16).[75] It is of particular interest for the argument of this paper that Galli had experience in the production of works in silver. Among the works mentioned in his nephew’s biography are four large silver salvers representing mythological themes commissioned by Prince Alessandro, for which Galli produced the models and oversaw their execution in silver.[76]

Reconstructing the Żebbuġ Evangelists Commission and Its Execution

Having set the scene for and discussed the various actors in the Żebbuġ Evangelists commission, it is now time to reconstruct the process of its execution. As stated earlier, most of what we know about the commission and execution of the four silver statues by Belli for the high altar of the Parish Church of St. Philip of Agira in Żebbuġ, Malta, comes from an 1853 article in the Giornale di Roma. From it we know that, having received the commission for four silver altar statues of the Evangelists from the Żebbuġ church, Belli, “with wise advice,” decided to base them on frescoes in the Casino Torlonia, which the Giornale attributes to Overbeck but which we now know were painted by Seitz after preliminary designs by Overbeck. We also know that the sculptor Galli was charged with making three-dimensional models for Belli’s silver statues.

Unfortunately, access to the Villa Torlonia at Castel Gandolfo has been prohibited for a long time, and no reproductions of the Overbeck/Seitz frescoes of apostles and evangelists in the villa’s chapel are available.[77] But several drawings for those frescoes are in the collection of the Museum Behnhaus Drägerhaus in Lübeck, including one representing the Evangelists Luke and John (fig. 17),[78] bearing clear similarities to the Maltese works and presumably to Seitz’s cycle. (No drawing representing the Evangelists Matthew and Mark has yet come to light.) It is likely that the Lübeck drawings served as the sources for the well-known engravings produced at an unknown date by Joseph Von Keller (1811–73), the German artist born in Linz am Rhein who was a professor of engraving at the Düsseldorf Academy and was active in Rome and London,[79] (figs. 18, 19), since they share the same chamfered outlines. Other versions of the Evangelists are also known to have been engraved by Keller’s younger brother Franz (1821–96).[80] Together with Overbeck’s drawings, the engravings by the Kellers give an idea of what the Torlonia Chapel frescoes may look like.

An attentive comparison between the Lübeck drawing and Joseph Von Keller’s prints with Belli’s Żebbuġ Evangelists (figs. 20–23) shows a number of disparities. Furthermore, a number of differences between the drawn and engraved works and Belli’s works in silver are noticeable. A comparison between the engraved and the three-dimensional Saint Matthew (see fig. 20), for example, reveals a protruding left knee and leg in Belli’s version, which are not visible in the printed work. An analogous case is seen in the knee of Belli’s Saint John the Evangelist (see fig. 23), which can be made out beneath the drapery folds. John’s right foot, which is altogether hidden in the engraved work, is also visible. Some liberties can also be observed in Saint Luke (see fig. 22), who presses his open book against his chest rather than holding it from below away from his body. The strongest parallels appear in Saint Mark (see fig. 21), who follows extremely faithfully the Overbeck/Keller prototype. Yet again, the saint rendered in silver has an ennobled aura which is absent in Keller’s known print. The other notable difference between the prints and the final works is registered in the haloes, which are transformed from a plain circle—much more in tune with Overbeck’s chaste iconography—to an ornamental element.

Conversely, the greatest divergences between the prints and the statues are in the positioning of the symbolic attributes which accompany the four saints. Matthew’s angel is placed on the left rather than on the opposite side and is turned to face the spectator while looking up toward his companion saint. The proportions seen in the print are retained, but the angel wears a short-sleeved garment in the silver work. Again, in Keller’s engraving, Luke’s ox appears on the right-hand side, while in the silver work it is placed on the left (see fig. 22). John’s eagle, on the other hand, has a tamer attitude in Belli’s final interpretation (see fig. 23). It is the lion of Saint Mark which remains the most faithful to the Overbeck/Keller archetype.

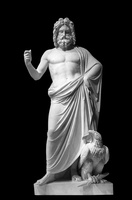

The process of transforming a flat drawing into a three-dimensional sculpture should have also presented an added challenge, one which Galli, given his huge experience as a sculptor, was certainly well-prepared to overcome. It is not known if Overbeck also provided drawings for the backs of the figures, but it seems that here Galli had the upper hand because, when examined from the back, they are perfectly comparable to his known sculptural works. In fact, the greatest parallels to the Evangelists’ modeling can be found in the two marble statues of mythological figures by Galli, now preserved at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome. These are the representations of Jupiter (fig. 24) and Apollo (fig. 25), both produced in 1838. Resulting from another Torlonia commission, these two works were originally placed in niches which adorned the hall housing Canova’s Hercules and Lichas at the palazzo in the Piazza Venezia.[81] Both Jupiter and Apollo share with the Evangelists the same solemn poses and dignified silence. There are further parallels in the modeling of the drapery folds. A direct comparison between the backs of Jupiter (fig. 26) and Saint Matthew (fig. 27) distinctly shows that the drapery folds fall in exactly the same manner, hence bringing the Evangelists closer to the Galli type.

These changes may be explained in various ways. Galli may have worked from Seitz’s frescoes, which may already have departed somewhat from Overbeck’s drawings. Translation from a two-dimensional drawing to a three-dimensional sculpture would have resulted in further “departures.” Alternatively, Galli may have worked from Overbeck’s preliminary drawings, but in the translation of two-dimensional models into the sculptural model, some changes would have been unavoidable. Another scenario is also possible. Overbeck may have produced a new set of drawings, based on his earlier drawings, that were more apt to be translated from drawings to sculpture. This last assumption gains some strength from Ciappara’s claim in Storia di Żebbuġ (History of Żebbuġ), that the works were produced “after Overbeck’s designs and with his assistance.”[82] Though “after Overbeck’s designs” would not necessarily mean that he made new ones (based on his drawings for the Torlonia frescoes) specifically for the Żebbuġ Evangelists, it does raise the possibility that he made a second set of full-scale drawings with their three-dimensional execution in mind.

In the absence of the actual models, the degree of liberty that Galli might have taken with the drawings by Overbeck remains unknown. In spite of the disparities discussed above, there is in general a direct and strong similarity between the engravings and the finished silver works. The modeling, poses and proportions of the figures, together with the arrangement of the drapery folds, largely tally with the details evident in the engravings. The works in silver, however, communicate an aura of formality, dignity, and sophistication which is not present in the printed works.

The concluding phase of the commission was in the hands of the silversmith. Indeed, the way the Evangelists can be perceived and appreciated today is very much the result of Vincenzo Belli’s impressive mastery of the art of silversmithing. The superlative and sophisticated outcome of these four remarkable works is a tribute to the silversmith’s artistic capabilities, thus transforming a significant model into an equally noteworthy creation. The artistic significance of the works is furthermore an accolade to the excellence of the entire tradition of the Belli family. A careful and close examination of the works reveals very skillful and disciplined hands at work. This can be seen in the articulation of the details, the smooth modeling of the surfaces, and the careful rendering of the different textures: skin, dress, hair, beards, feathers, and fur. The fastidious and sensitive tooling of the chisel is breathtaking (fig. 28). All these elements coalesce to create a veritable triumph of workmanship which wonderfully brings together the collaborative effort of the artists involved and transports to Malta the very spirit of the Eternal City.

Conclusion

The four silver Evangelists by Belli the Younger that decorate the high altar of the Parish Church of St. Philip of Agira in Żebbuġ, Malta, exemplify the strong artistic ties that this small island, sixty miles south of Sicily, maintained with Rome, one of the great international artistic centers of Europe. As this study has shown, a thorough analysis of the history of the execution of the four figures shows that they are the product of international cooperation between several artists, working in different media, who together were responsible for the translation of a set of drawings by a German artist, already used as models for frescoes in an Italian villa, into four intricate silver figures produced by a Roman metalsmith after three-dimensional “translations” of the drawings by an Italian assistant of a Danish sculptor.

The commission brought together several well-known, mid-nineteenth-century artists working and living in Rome, all of whom had carried out important religious as well as secular commissions in the papal city. Indeed, it is fascinating to note how a commission coming from a provincial town on the remote and tiny island of Malta, geographically located at the periphery of Europe, was able to tap and secure the very same artists and workshops who were working for key patrons, including the Pope himself, in one of the great artistic centers of the Western world. The lure of all things Roman, which had a long history in Malta that culminated in the nineteenth century, had led the Maltese to establish contacts with artists and patrons at the heart of Roman culture and commission works that permitted its churches to compete in artistic refinement with most churches in the Eternal City. As the Evangelists commission clearly and strongly manifests, the story of art in Malta is thus aligned with a remarkable group of artists operating in Rome and, by extension, in the larger European artistic milieu.

Notes

All translations, unless otherwise noted, are my own.

[1] “Il sig. Vincenzo Belli scultore in metallo che in questo medesimo giornale fu lodato per due suoi egregi lavori di Paliotto d’altare in argento, eseguiti per il Tempio di S. Paolo di Valletta in Malta, è tornato or ora a darci novello e non men distinto saggio nell’arte sua con due statue per altare rappresentanti gli Evangelisti S. Marco e S. Giovanni, alle quali terranno dietro quelle degli altri due Evangelisti San Luca e S. Matteo.” (Mr Vincenzo Belli, metal sculptor, who in this same newspaper has been praised for two excellent silver antependia produced for the church of St. Paul in Valletta in Malta, has returned with new and no less distinguished essays in his art with two altar statues representing the Evangelists Saint Mark and Saint John, which will follow those of the other two Evangelists Saint Luke and Saint Matthew). “Belle Arti: Scultura Metallica,” Giornale di Roma, April 27, 1853, 376. This same article appeared a few days later in Malta, in the newspaper L’Ordine. “Belle Arti: Scultura Metallica,” L’Ordine, May 6, 1853, 4082.

[2] Today they are placed on the second gradine of the altar, but they were originally intended for the first gradine before new altar statues were commissioned in the first half of the twentieth century.

[3] Salvatore Ciappara, Storia del Żebbuġ e sua parrocchia con molte e svariate notizie risguardanti la stessa terra e parrocchia (Malta, 1882), 87–88.

[4] Mark Sagona, “The Ecclesiastical Decorative Arts in Malta 1850–1900: Style and Ornament” (PhD diss., University of Malta, 2014), 51–55.

[5] Ciappara, Storia del Żebbuġ, 87.

[6] Untitled article in L’Ordine, April 3, 1852, 2072.

[7] “Belle Arti,” L’Ordine, September 2, 1853, 4151.

[8] Keith Sciberras, Roman Baroque Sculpture for the Knights of Malta (Malta: Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti, 2004).

[9] Sciberras, Roman Baroque Sculpture, 164–76.

[10] Mark Sagona, “Gothic Revival Influences on Europe’s Border: Change and Resistance in Malta between Decorative Arts and Architecture,” Journal of the Decorative Arts Society, 1850 to the Present, no. 45 (2021): 31.

[11] Mark Sagona, “The Significance of Luigi Fontana’s St. Philip of Agira in the Context of Nineteenth-Century Art in Malta,” in Statva Argentea: Luigi Fontana’s Silver Statue of Saint Philip in Żebbuġ, ed. Philip Balzan, Joe P. Borg, and Philip Sciortino (Malta: Għaqda Każin Banda San Filep, 2013), 159–71.

[12] For a brief survey of nineteenth-century art in Malta, see Mark Sagona, “Michele Bellanti: New Discoveries and a Fresh Reading of His Ecclesiastical Works,” in The Bellanti Family: Contributions to Art and Culture in Malta, ed. William Zammit (Malta: Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti, 2010), 140–41; and Mark Sagona, “The Artistic Context for Salvatore Dimech’s Annunciation of the Virgin at Ħal Balzan Parish Church: A Critical and Analytical Study,” in Il-vara titulari tal-Lunzjata ta’ Ħal Balzan, ed. Carmel Bezzina (Malta: Balzan Parish Church, 2019), 53–91.

[13] “con savio avviso volle il Sig. Belli che ritraessero il concetto, e la purezza di modi degli Evangelisti dipinti dal pennello dell’esimio Sig. Cav. Overbeck nella cappella del Casino Torlonia a Castel Gandolfo; nel che è stato egli cosi bene secondato dallo scultore chiarissimo Sig. Galli, che gli n’ebbe forniti i modelli in plastica, che nel vero non puo’ desiderarsi cosa piu conforme ai sani principi dell’arte.” “Belle Arti: Scultura Metallica,” Giornale de Roma, 376.

[14] Sagona, “The Ecclesiastical Decorative Arts,” 53.

[15] Giovanna Capitelli, Mecenatismo pontificio e Borbonico alla vigilia dell’unità (Rome: Viviani, 2011), 184.

[16] Ciappara, Storia del Żebbuġ, 87.

[17] “Il sigr. Cav. Overbech [sic] venuto testè al mio studio per vedere i due detti Evangelisti (S. Marco e S. Giovanni) mi ha fatto mille espressioni di approvazione.” (Overbeck came himself to my studio to see the two mentioned Evangelists and he showed a thousand signs of approval). Ciappara, Storia del Żebbuġ, 87.

[18] Sagona, “The Significance of Luigi Fontana’s St. Philip of Agira,” 168–69.

[19] Anthony Gatt, “The Statue, Its Masters, and Further Connections with Malta,” in Fontana’s St. Philip of Agira: Contextual, Stylistic, and Technical Considerations, ed. Joe P. Borg (Malta: Żebbuġ Parish Church, 2021), 5.

[20] Mark Sagona, “The Ecclesiastical Decorative Arts,” 30–34.

[21] The story of the Nazarenes in Rome is told in Keith Andrews, The Nazarenes: A Brotherhood of German Painters in Rome (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964).

[22] Emmanuel Fiorentino, Il-Pittura f’Malta fis-Seklu Dsatax (Malta: Pubblikazzjonijiet Indipendenza, 2006), 35.

[23] Antonio Espinosa Rodriguez, “The Nazarene Movement and Its Impact on Maltese Nineteenth-Century Art” (master’s diss., University of Malta, 1997), 27–45.

[24] Artists within Hyzler’s following included his own younger brother Vincenzo, Antonio Falson (1805–66), and later, Giuseppe Calleja (1828–1915). Vincenzo Hyzler frequented Overbeck’s studio in Rome between 1839 and 1843 and collaborated with the German master on the Crucifixion for the Sanctuary of the Holy Crucifix in Stresa on the Lago Maggiore.

[25] “Belle Arti,” 4151.

[26] Alberta Campitelli, “La Scuola di Thorvaldsen nelle Ville Torlonia di Roma e Castel Gandolfo,” in Thorvaldsen: L’Ambiente, L’Influsso, Il Mito, ed. Patrick Kragelund and Mogens Nykjær (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1991), 59.

[27] Guido Galli, “Biografia di Pietro Galli,” in La Vicenda di una Dimora Principesca Romana: Thorvaldsen, Pietro Galli e il demolito Palazzo Torlonia a Roma, ed. Jörgen Birkedal Hartmann (Rome: Fratelli Palombi, 1967), 99.

[28] Ernesto Bianchi, “Pietro Galli,” in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 51 (Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1998), 632.

[29] Galli, “Biografia di Pietro Galli,” 100.

[30] Ulrich Pfisterer, “Workshop Cult and Workshop Knowledge: Production and Portraits in Thorvaldsen’s Studio,” in Face to Face: Thorvaldsen and Portraiture, ed. Jane Fejfer and Kristine Bøggild Johannsen (Copenhagen: Strandberg, 2020), 68–77.

[31] Costantino G. Bulgari, Argentieri, Gemmari e Orafi d’Italia (Rome: Lorenzo del Turco, 1958), 124–25.

[32] Works by Antonio Belli in Malta have been identified at both St. Paul’s Shipwreck Church, Valletta, and at the Mdina Cathedral. Sagona, “The Ecclesiastical Decorative Arts,” 114–16.

[33] Bulgari, Argentieri, Gemmari e Orafi, 129.

[34] Zenaide Giunta di Roccagiovine, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (1965), s.v. “Belli.”

[35] Bulgari, Argentieri, Gemmari e Orafi, 124–25, 127; and Anna Maria Pedrocchi, Argenti Sacri nelle Chiese di Roma dal XV al XIX secolo (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2010), 192.

[36] Bulgari, Argentieri, Gemmari e Orafi, 125.

[37] See the design for a centerpiece at the Cooper-Hewitt, Inv. 1938-88-5779.

[38] Various works by members of the Belli family belong to Roman churches. See Pedrocchi, Argenti Sacri, 112–14, 121–22, 128–29.

[39] Untitled article in L’Ordine, November 25, 1859, 4.

[40] Untitled article in L’Ordine, December 23, 1859, 3–4; and “Necrologia di Vincenzo Belli Argentiere e Scultore in Metalli,” Giornale di Roma, December 3, 1859, 1099.

[41] Two standing angels are also present in the beautiful papal chair in white marble and gilt-bronze in the same church, with its splendidly repetitive scrolls and its stylized acanthus, palmettes, and anthemions. Additionally, the trio of silver lamps hanging in the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament at Orvieto Cathedral are also of superb quality.

[42] Albert Ganado and Antonio Espinosa Rodriguez, An Encyclopedia of Artists with a Maltese Connection (Malta: Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti, 2018), 53.

[43] Sagona, “The Ecclesiastical Decorative Arts,” 23–24; and Mark Sagona, “Changing Artistic Taste in Malta at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century,” in At Home in Art: Essays in Honour of Mario Buhagiar, ed. Charlene Vella (Malta: Midsea Books, 2016), 294–95.

[44] Untitled article in L’Ordine, April 3, 1852, 2072.

[45] The receipt is found in Libro d’Introito ed Esito No. 2, n.p., Archives of the Confraternity of St. Homobonus, St. Paul’s Shipwreck Church, Valletta.

[46] Untitled article in L’Ordine, February 11, 1853, 4034.

[47] Sagona, “The Ecclesiastical Decorative Arts,” 47.

[48] “Feste Religiose,” L’Ordine, February 16, 1855, 4458. The artifacts carry Belli’s maker’s marks and the assay mark of the Pontifical State.

[49] For details about the commission, see Sagona, “The Ecclesiastical Decorative Arts,” 55–59; and Mark Sagona, “The Decorative Arts in Gozo: Artistically Significant Ecclesiastical Specimens from the Nineteenth Century,” in Identity of an Island – Gozo: Art between Past and Present, ed. Mark Sagona (Malta: Midsea Books and Teatru Astra, 2022), 53–55.

[50] “Feste e Divozioni,” L’Ordine, December 31, 1858, 5276. The work is also mentioned in Achille Ferres, Descrizione Storica delle chiese di Malta e Gozo (Malta, 1866), 222.

[51] An extract from the article “Scultura Metallica,” Giornale di Roma, December 29, 1858, was published in the article “Belle Arti,” L’Ordine, January 7, 1859, 4.

[52] The date of the actual remodeling is unknown.

[53] Receipt no. 51, Ricevuti dei pagamenti dei lucri della Ven. Confraternità del Carmine della Valletta: Beni segregati delle Procure Capitali Fruttiferi 1860–1868, vol. 227, n.p., Archives of the Confraternity of the Virgin of Mount Carmel, Carmelite Church, Valletta.

[54] Stefano Grandesso, “La Vendita delle disiecta membra di palazzo Torlonia a piazza Venezia,” in Capitale e Crocevia: Il mercato dell’arte nella Roma Sabauda, ed. Andrea Bacchi and Giovanna Capitelli (Milan: Silvana, 2020), 257.

[55] For the story of the Torlonia family, see Hartmann, La Vicenda di una Dimora Principesca Romana, 11; and Daniela Felisini, Alessandro Torlonia: The Pope’s Banker (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 17.

[56] Felisini, Alessandro Torlonia, 17.

[57] Hartmann, La Vicenda di una Dimora Principesca, 11.

[58] Felisini, Alessandro Torlonia, 18.

[59] Felisini, Alessandro Torlonia, 23.

[60] The swift ascent of the Banco Torlonia and the business ventures of Giovanni Torlonia are recounted in detail in Felsini, Alessandro Torlonia, 18–49.

[61] Felisini, Alessandro Torlonia, 24, 35; and Hartmann, La Vicenda di una Dimora Principesca, 11, 21.

[62] Hartmann, La Vicenda di una Dimora Principesca, 12. The façades of the churches of St. Pantaleone and Santi Apostoli in Rome were both remodeled by Valadier.

[63] Campitelli, “La Scuola di Thorvaldsen,” 59.

[64] Hartmann, La Vicenda di una Dimora Principesca, 12–13.

[65] Campitelli, “La Scuola di Thorvaldsen,” 59.

[66] Campitelli, “La Scuola di Thorvaldsen,” 60.

[67] Felisini, Alessandro Torlonia, 60.

[68] Hartmann, La Vicenda di una Dimora Principesca, 69.

[69] Margaret Howitt, Friedrich Overbeck: Sein Leben und Schaffen (Freiburg im Bresigau: Herder, 1886), 149–50.

[70] Hartmann, La Vicenda di una Dimora Principesca, 11.

[71] Campitelli, “La Scuola di Thorvaldsen,” 73.

[72] “Roma – Scultura – Apollo che suona la lira attorniato da pastori,” Il Tiberino: Giornale Artistico con varietà, June 1, 1840, 1. My thanks to Prof. Giovanna Capitelli for bringing this source to my attention.

[73] Campitelli, “La Scuola di Thorvaldsen,” 68–71.

[74] Barbara Steindl, “Una committenza Torlonia: La Cappella Torlonia a San Giovanni in Laterano,” in Kragelund and Nykjær, Thorvaldsen: L’Ambiente, L’Influsso, Il Mito, 83.

[75] Steindl, “Una committenza Torlonia,” 85.

[76] Galli, “Biografia di Pietro Galli,” 99.

[77] Personal communication with Giovanna Capitelli, Università Roma Tre, July 11, 2023.

[78] The five chalk drawings, all housed in the collection of the Museum Behnhaus Drägerhaus, Lübeck (formerly Museen für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte), are Thomas and Philip (Inv. 1926/22), Simon and Andrew (Inv. 1926/23), Peter and Paul (Inv. 1926/24), and Matthias and Barnabas (Inv. 1926/25)—all of which were acquired in 1926 with unknown provenance—and Luke and John (Inv. 2004/139), received as a donation in 2004. My thanks to Dr. Alexander Bastek for his generous assistance in the identification of these works.

[79] Emmanuel Bénézit, Dictionnaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs, vol. 6 (Paris: Librarie Gründ, 1976), 187. Bénézit claims that Joseph Von Keller went to work in Rome in 1841. This could be the date when he came across Overbeck’s original works which served as models for his engravings.

[80] Emmanuel Bénézit, Dictionnaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs, vol. 6 (Paris: Librarie Gründ, 1976), 187. The Keller prints were employed as the prototypes for the respective marquetry panels in the new choir stalls at Mdina Cathedral in Malta, which were inaugurated in December 1876. The mastermind of this commission was the erudite and well-traveled Canon Paolo Pullicino (1815–90), one of Malta’s most important nineteenth-century art patrons. See Mark Sagona, “Malta and the Renaissance Revival: Ecclesiastical Decorative Arts at the Crossroads of Britain and Italy,” Journal of the Decorative Arts Society, 1850 to the Present, no. 39 (2015): 17–18; and Peter Aquilina, “The Renaissance Revival Choir Stalls and Lectern at Mdina Cathedral: Their Maltese and European Decorative Arts Context” (bachelor’s [honors] diss., University of Malta, 2023), 53.

[81] Hartmann, La Vicenda di una Dimora Principesca, 29. There were twelve niches in all, housing works by, among others, Tenerani, Rinaldo Rinaldi (1793–1873), and Antonio Solà (1782/3–1861).

[82] “Nel 1853 si lavorarono in Roma dal Prof. Vincenzo Belli le quattro statuette degli Evangelisti sul disegno e coll’assistenza di Overbech [sic].” Ciappara, Storia del Żebbuġ, 87.