The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends

National Portrait Gallery

London, England

February 12–May 25 2015

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

New York, New York

June 30–October 4, 2015

Catalogue:

Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends.

Edited by Richard Ormond with Elaine Kilmurray.

New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2015.

256 pp.; 135 color illus.; index.

$60.00

ISBN: 978-0847845279

In the last decade, a succession of John Singer Sargent exhibitions have focused on the artist’s impressionistic, dappled light and images of elegant women, swathed in lush fabric. While these familiar tropes certainly appear in the Metropolitan Museum’s recent exhibition, Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends, the exhibition's curators took pains to demonstrate that the artist’s interests expanded well beyond grand manner portraits of upper class sitters. By emphasizing themes of experimentation and intimacy, the show carved out a new space for the productive consideration of John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) as a portraitist, significantly amplifying his more familiar body of work as a society painter. In doing so, the retrospective reminded visitors not only of Sargent’s breadth and facility, but also of his place within a transnational community of artists, performers, authors, and prominent expatriates. This undercurrent of artistic exchange revealed anew the influence of Sargent’s friendships on his artistic growth. As the curators aimed to elucidate, these relationships with creative personalities, ranging from William Butler Yeats and Vernon Lee to Edwin Booth and Claude Monet, informed Sargent's stylistic experimentation and affected his episodes of informal and idiosyncratic portraiture.

First exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery in London, Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends was conceived by Richard Ormond, Samuel H. Kress Professor at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, former Deputy Director of the National Portrait Gallery, London, and Sargent’s great-nephew. In addition to co-authoring the Sargent catalogue raisonné project with Elaine Kilmurray, Ormond has contributed to a number of Sargent exhibitions and catalogues in the past decade, including John Singer Sargent’s Watercolors (2013), Sargent and the Sea (2009), and Sargent and Italy (2008).

Led by Elizabeth Kornhauser, the Alice Pratt Brown Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture, and Stephanie L. Herdrich, Assistant Research Curator of the Metropolitan Museum’s American Wing, the curators of the New York iteration of the exhibition drew from the Metropolitan Museum’s extraordinary permanent collection in order to add depth and variety to the works on display. The exhibition expanded upon the categories of “friendship” and “portraiture” by including pencil and charcoal drawings, chalk renderings, and oil sketches of colleagues, mentors, and acquaintances in addition to grand-manner oil paintings. Together, these created a more generative picture of Sargent’s work and emphasized the capaciousness of the artist’s geographical and social networks. Many of the figural works on display have been categorized as character studies or genre scenes in previous exhibitions or catalogues. By hanging them alongside more traditional portraits, the curators queried genre distinctions and visitors’ assumptions, making the point that, for Sargent, portraits were a touchstone of experimentation.

With over ninety paintings, drawings, and preliminary studies by Sargent, the scope and scale of the show suited the generous proportions of the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Exhibition Hall, which was divided into five rooms to parallel the trajectory of the corresponding catalogue. The exhibition was arranged both chronologically and by geographic region to comprise a cross-section of Sargent’s oeuvre between roughly 1879 and 1922, beginning in Paris and moving through Broadway, London, the United States, and Europe. In New York, curators extended the impressive collection of permanent holdings and loans from museums and private collections—and the catalogue’s course—by appending a reading room in which watercolors and works on paper from the Metropolitan Museum’s permanent collection were displayed.

Ormond’s introduction to the exhibition catalogue establishes its aim to challenge “. . . the conventional view of John Singer Sargent as a bravura painter of the old school, of limited imagination and originality. What materializes here is a painter in the vanguard of contemporary movements in the arts, in music, in literature and the theatre” (9). In this vein, Ormond and his colleagues aimed to shift the conversation away from Sargent as an autonomous artistic genius, re-staging his portraiture with recourse to his international community and extensive networks. Ormond later notes that Sargent’s relationships extended far beyond the British art world to include painters such as “Italian Giovanni Boldidi, the Swede Anders Zorn and the Spaniard Joaquín Sorella” (19).

In addition to Ormond’s essay, the exhibition catalogue includes contributions by established Sargent scholars Marc Simpson, Elaine Kilmurray, Barbara Dayer Gallati, Erica E. Hirshler, Trevor Fairbrother, and H. Barbara Weinberg. In their respective essays, these scholars follow the organization of the physical exhibition and take on Sargent’s chronological movements through Paris, Broadway, London, Boston, New York, and Europe (fig. 1). The catalogue concludes with Weinberg’s useful timeline of selected international political, economic, social and cultural events from 1856 to 1925. All essays advance the exhibition’s broader objective to emphasize Sargent’s diverse practices and engagement with “art, music, literature, and the spectacle” as encouraged by his motley network of friends (31).

This goal was manifested in an installation that prompted new discourses by juxtaposing works not usually paired together. Subtle changes were also made to the physical space of the exhibition hall. The clean, modern lines and minimalist aesthetic deployed by Brian Butterfield, the Metropolitan Museum’s Senior Exhibition designer, forcefully held the temptation for Gilded Age nostalgia at bay. In the initial vestibule, crisp white walls surrounded a rectangular glass window through which visitors could peer into the second gallery space (fig. 2). This design decision reinforced a commitment to porous boundaries between galleries, and thus a more fluid conversation between works created in different years and inspired by different locations. Meanwhile, the adjacent introductory wall text concisely established Sargent’s protean nature and social acumen among his theatrical, musical, and literary contemporaries.

Those who chose to follow the audio tour, beginning in this entryway, would hear not only commentary by the exhibition’s curators, but also observations by Katy Grannan, a contemporary portrait photographer. By adding yet another artistic dialogue to the mix, this auditory component reflected the continued relevance of Sargent’s innovations in the twenty-first century and supported the exhibition’s interest in transnational, trans-temporal artistic exchange.

Paris, 1874–1885

In the first room, “Paris: 1874–85,” an introductory panel introduced Sargent’s early biography and artistic training at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and in the atelier of Carolus-Duran. Although Paris served as his home base, this room deemphasized Sargent’s critical trips to Spain, Venice, the Netherlands, and Morocco, focusing instead on his Parisian colleagues and mentors including Carolus-Duran, François Flameng, and Auguste Rodin.

The term “portrait,” the unifying generic theme of the exhibition, was immediately complicated thanks to the inclusion of Rehearsal of the Pasdeloup Orchestra at the Cirque d’Hiver (1879–80), one of the first paintings encountered in the gallery (fig. 3). This study of Jules-Etienne Pasdeloup’s orchestra features a grisaille palette and blurred amphitheater. By eliminating detail or identifiable likenesses, Sargent draws attention away from specific musicians in order to highlight the aural experience of the orchestra itself. While this image certainly reinforced Sargent’s interest in performance and spectacle, it could have also anchored an exhibition devoted entirely to Sargent’s discipleship of Wagner and love of music, or an exploration of Sargent and the performing arts more broadly. In the context of this exhibition, the experimental study reinforced Sargent’s aesthetic response to the Concert Populaires conducted by his Parisian contemporary. Nearby, visitors congregated around the Portrait of Edouard and Marie-Loise Pailleron (1880), which was united in the gallery space with flanking portraits of the sitters’ parents (fig. 4). The children’s penetrating gazes confront the viewer, and their distinct identities unsettle conventions of traditional portraiture, particularly portraits of young sitters who were typically rendered as deferential accessories to prominent parents.

A particular strength of this initial room was the inclusion of multiple renderings of the same figure to demonstrate Sargent’s stylistic range and experimental tendencies. French poet and novelist, Judith Gautier, for example, was presented twice; once in 1885 as a stylish sitter costumed à la japonaise, and again in an impressionistic sketch entitled A Gust of Wind (1886–87). Paul Helleu also appears twice—in an 1880 pastel on brown wove paper and later in a double portrait with François Flameng.

“Paris” culminated with Sargent’s iconic Madame X (1883–84), which supervised the gallery from its place of honor in a recessed niche in the rear wall (fig. 5). Although the painting was omitted in the exhibition’s London installation, and does not comfortably fall under the category of artist or friend, the choice to include Madame X, one of the stars of the Metropolitan Museum’s American wing, did not distract from the other works in the gallery. On the contrary, the painting’s presence strengthened the magnetism of Dr. Pozzi at Home (1881). Pozzi, in his vibrant red robe, served as a worthy and appropriate foil to Madame X (fig. 6). Sargent’s pictures of the scandalized Parisienne and adjacent gynecologist pulsate with sensual facture and saturated pigment. Dr. Pozzi’s power and elegance are especially evident in his hands, the charged site of his surgical touch. This juxtaposition with Madame Gautreau called to mind Alison Syme’s deft analysis of the two works: “Unlike the softly palpating portrait of Dr. Pozzi, Gautreau’s painting as a whole is coldly analytical, her razor-sharp, surgically precise silhouette unusual, and, at the same time, critically unsuccessful, for Sargent.”[1]

Although this room successfully reinforced the curators’ aim to address Sargent’s engagement in contemporary art and literature, it failed to attend to the changes in visual media at the time, and the relationship between Sargent’s portraits and the shifting urban environment of Paris. The advent of the locomotive, telegraph, electric street lighting, and steel bridges instigated particularly dramatic changes to the geographical landscape of the city. Meanwhile, advancements in photography and print technology arguably led to a nostalgic desire for acts of human agency and traces of human touch. A viewer would have been more engaged if prompted from the onset to reflect on how these portraits bespeak such epochal shifts and, by extension, how their materiality might respond to their particular time and place of origin.

Broadway: The English Countryside, 1885–1889

As the exhibition continued to trace Sargent’s movements through time and space, visitors arrived next in “Broadway,” a liminal moment in Sargent’s career when he paused between Paris and London to spend time in the English countryside (fig. 7). Located in a Cotswold village, Broadway served as a colony of American and English writers and artists in the late-nineteenth century including Frank Millet, Edwin Austin Abbey, Frederick Barnard, Henry James, and Edmund Gosse.

As with the previous gallery, “Broadway” operated around a clearly delineated and recessed anchor, in this case, Garden Study of the Vickers Children (1884) (fig. 8). Notably absent from this gallery was Carnation Lily, Lily Rose (1885–86), one of Sargent’s best-known works and an example of his experimentation with English Aestheticism en plein air. More interesting, however, were the preparatory studies that revealed his process and gestural facture. In addition to Garden Study of the Vickers Children, the Metropolitan Museum included a double-sided preparatory pencil drawing of Dorothy and Polly Barnard, acquired mere months before the exhibition’s opening and here placed in dialogue with the larger oil studies of the same scene (fig. 9). This thoughtful juxtaposition served as an effective didactic tool, allowing visitors to engage with, and learn about, Sargent’s method without the inclusion of extra wall texts or invasive touch screens.

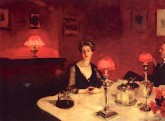

One particularly evocative group of portraits within the “Broadway” portion of the exhibition hung on the far side of the long gallery space. While not the largest or best known of the works on view, these four paintings of destabilized domestic spaces, Robert Louis Stevenson and his Wife (1885), Fête Familiale (The Birthday Party) (1887), Robert Louis Stevenson (1887), and A Dinner Table at Night (1884) shared a rich red tonality that enticed exhibition visitors. In A Dinner Table at Night (1884) (fig. 10), Sargent adheres to upper class conventions of a well-appointed room only to subvert the terms of his fashionably organized interior by deploying unsettling vacancies and denying the viewer a coherent narrative. Upon closer inspection, one can see where Sargent exposed the canvas throughout the painted white tablecloth, which further disrupts the viewer’s illusion of the dining room. The work is generally quite thinly painted, a quality made more vivid in those passages where Sargent scraped away layers of paint and ground wash to reveal high points of the canvas weave. This is thrown into relief thanks to the impasto highlights added to the still-life elements in the foreground using a heavily laden dry brush.

Other portraits in this room drew attention to the performance of painting by depicting an artist at work. Dennis Miller Bunker Painting at Calcot (1861–90) and An Out-of-Doors Study (1889) emphasize body language over exact likeness and demonstrate the casual environment and palpable energy of the Broadway artist colony.

London, 1889–1913

Section three, “London,” proved the most nebulous category within the exhibition, containing the widest variety of painted and drawn portraits. Beginning with the striking Ellen Terry as Lady MacBeth (1889), however, the question of role-playing and identity emerged as one unifying theme. In addition to depictions of dancers, singers, and actors, whose identities as performers were explicit, Sargent’s painting of Mrs. Charles Hunter (1898) revealed how the sitter fashioned her identity through costume and conduct as a society figure and Edwardian hostess. This productive cluster encouraged such insight into flamboyance and theatricality in the context of both public and private personas (fig. 11).

Elsewhere in the gallery other paintings likewise accentuated Sargent’s attentiveness to the subtleties of gesture, movement and theatricality. Recessed in a prominent niche on the gallery’s right was Carmencita (1890), flanked by A Javanese Dancing Girl (1889) and La Carmencita Dancing (1890). A video of Carmencita herself from Edison studios was subtly placed on an opposing wall and tastefully recessed (fig. 12).

Complementing A Javanese Dancing Girl (1889) was Sargent’s Javanese Dancers Sketchbook and graphite sketch, After “El-Jaleo,” shown in a nearby display case. These works on paper certainly pertained to themes of performance, exoticism, and movement, but did not fit neatly into the category of “portrait.” The curators explored this tension between traditional portraiture and intimate, unconventional likenesses in the initial wall texts, but did not revisit its implications in the context of the Javanese dancers. The gallery’s wall text and corresponding catalogue entries instead focused on the womens’ physical characteristics, mask-like features, and gestures.

This gallery space also included more conventional, large-scale portraits such as Léon Delafosse (1895), W. Graham Robertson (1894) with his arm akimbo, the distinguished Coventry Patmore (1894), the Metropolitan Museum’s own Mrs. Hugh Hammersley (1892), and a series of charcoal portraits that emphasize Sargent’s rapid technique. The presence of Eleonora Duse (1893), an Italian actress, helpfully demonstrated this swift process: the portrait was left unfinished when the subject abruptly left the room after only one hour.

United States, 1887–1922

“United States,” the fourth of five geographical galleries, did not appear as a distinct unit within the National Portrait Gallery’s installation. The addition of this gallery in the New York venue at once allowed for the inclusion of many prominent works from the Metropolitan Museum’s American wing and had the effect of emphasizing Sargent’s Americanness. Isabella Stewart Gardner (1888), which rarely leaves its namesake museum in Boston, presided over the gallery space, which included members of the Players Club, a nineteenth-century social club for actors in New York City (fig. 13). This gallery further developed themes of identity, performance, and costume, establishing thematic connections with the previous “London” gallery and its portraits.

The portrait of Shakespearean actress Ada Rehan (1894–94) appeared after a year of cleaning and conservation work that successfully removed a discolored varnish over the portrait’s surface (fig. 14). Rehan, portrayed in an ornate costume and lavish setting, typifies how Sargent took just as much care rendering the details of the total work—the tapestry behind the sitter and reflective fabric of her gown—as he did with her distinctive facial features. Once again, Sargent’s emphasis shifts from the depiction of a likeness, a move that reflects the artist’s continuing disengagement with the fundamental terms and conventions of portraiture.

A recurring theme throughout the exhibition was Sargent’s inclusion of brushes and palettes within his portraits of artists, pictorial elements that emphasized the act of art making and the performance of artistic identity. One such painting, William Merritt Chase (1902) clearly takes up notions of artistic identity in the late-nineteenth century (fig. 15). Sargent appears to have been sensitive to the expectation that artists would act and dress to conform to a recognizable “type” and reportedly insisted that Chase wear “his working rags” instead of the frock coat to visually cement Chase’s status as an artist (199). One wishes that it would have been possible to display in this gallery Sargent’s own palette, currently housed in the Harvard Art Museum, so that viewers could consider the arrangements of pigments and physical presence of paint, as it relates to Sargent’s alleged instructions to his students: “Do not starve your palette.”[2]

Europe, 1899–1914

Intimate in scale, the final gallery, “Europe,” showcased Sargent’s transnational friendships and ceaseless peregrinations (fig. 16). In An Artist in His Studio (Ambrogio Raffele) (1904), Sargent’s inclusion of paintings within the painting not only identifies the interior as an artistic domain, but also calls attention to the act of creation in a larger sense.

Across the room, The Fountain, Villa Torlonia, Frascati, Italy, (1907), served as a focal point amongst a collection of holiday pictures, drawing visitors who recognized the image immediately from the exhibition’s publicity materials or the cover of the catalogue. This image portrays the artist Jane Emmet de Glehn at work painting en plein air in Italy. Also painted in Italy, Villa Torre Galli: the Loggia (1910) depicts a scene of leisure and gives visual form to the Italian phrase Sargent knew well: “Il Dolce Far Niente” or, “The Sweetness of Doing Nothing.” At the same time, this scene characterizes Sargent’s pervasive interest in liminal and threshold spaces that focus the tension between interior and exterior. Other paintings in this room, including Group with Parasols (Siesta) (1904) and In the Garden (Corfu) (1909) further asserted Sargent’s ability to capture a restful outdoor scene while simultaneously asserting the artifice and constructed quality of his surfaces.

Sargent at the Met: Watercolors and Drawings

The Cantor Exhibition Hall’s reading room housed the final room of the exhibition, which featured twenty-one watercolors and drawings from the Metropolitan Museum’s permanent collection (fig. 17). Emphasizing Sargent’s acumen as a draftsman and watercolorist, the gallery showcased the museum’s corpus of Sargent’s figural works on paper, and situated Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends in conversation with the popular 2012 exhibition Sargent’s Watercolors.

Many of the pictures included in this room portrayed young men, often bathing or modeling in the nude. Mercifully, the curators opted to eschew the tired debate over Sargent’s sexual orientation and to instead place Sargent’s magnificent studies of the male body in dialogue with informal sketches of Paul Helleu and other friends from his Parisian artistic circle. By juxtaposing private and public works on paper, the curators encouraged visitors to consider complex ideas about identity rather than rely on circumstantial evidence and outmoded stereotypes.

Tellingly, the curators applied the same juxtapositional logic to query other aspects of identity and representation. On a wall containing bright depictions of a Venetian canal, Spanish architectural detail, and the lighthearted Woman with Collie (1890), viewers were confronted with Arab Woman (1905–06), a watercolor of a veiled woman in the Middle East, perhaps rendered during Sargent’s trip to Jerusalem (fig. 18). Here, Sargent asserts the material identity of each mark and dashing gesture, using paint as a permeable screen and extending the woman’s veil into a dynamic, energetic field of color. Sargent artfully ensures that we are made keenly aware of the illusionary interplay of texture that dissipates as the beholder moves closer to the canvas’s painted surface.

Conclusions

In an 1883 letter to his brother, FitzWilliam Sargent speaks proudly of his son’s accomplishments and integrity:

He [John Singer Sargent] seems to be respected, even admired and beloved (according to all accounts) for his talent and success as an artist, for his conduct and character as a man. His work is a pleasurable occupation to him and brings him a very handsome income. He travels about in countries, which provide him with materials for his pictures as well as bread and butter and elements of health and enjoyment. He is well received everywhere for his manners are good and agreeable. He is good looking, plays the piano well and dances well, converses well, etc., etc. In short, he has given us, his parents great satisfaction so far . . . [3]

Like all Sargent exhibitions, Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends risked reiterating the familiar vision of Sargent as a well-mannered conversationalist and agreeable son instead of inciting new dialogues. Its encyclopedic impulse, while impressive, at times felt hurried and incomplete. Moreover, the concurrent diachronic and geographic presentation of Sargent’s oeuvre failed to capture the peripatetic Sargent, equally at home in England, France, and the United States among a transatlantic coterie of artists and friends. The exhibition’s organization around these geographical moorings further limited thoughtful reflection on Sargent’s extensive social and geographic circuits. The bracketing of non-Western travel in particular was a missed opportunity to investigate Sargent’s artistic output in the Middle East and Morocco in the context of thematic and technical experimentation. Although Sargent’s travels to Tangiers, Cairo, Jerusalem, Bursa, and Istanbul typically resulted in studies of anonymous figures, they often paralleled his society portraits in compositional arrangement. The inclusion of An Egyptian Woman (1890–91) and Egyptian Woman with Earrings (1890–91), both owned by the Metropolitan Museum, could have sparked stimulating reflections when placed in relationship to finished, gestural portraits of the same scale such as Mrs. Frank Millet (1885–86) or Antonio Mancini (1902).

To clarify Sargent’s relationship to Orientalism and frequent depictions of veiled or so-called “exotic” women who appear throughout the exhibition, it would have been useful to also include Women Approaching (1890s), a watercolor in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection that employs traces of pigment to suggest the veils of female worshippers exiting a mosque. Regrettably, one of the few wall texts that engaged with this theme noted Sargent’s “longstanding interest in the exotic” without defining the issues surrounding the concept of “exotic” women or situating these works in a larger art historical context. Indeed, at times, the shadow of Orientalism haunted the exhibition’s attempts to demonstrate Sargent’s progressive friendships and avant-garde techniques.

As pictures that reflect Sargent’s persistent interest in issues of identity, performance, and surface, the portraits of artists and friends on display in this exhibition are clearly not outliers. Indeed, by the end of Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends, the curators had very effectively secured their place within his long career. This exhibition commendably exposed both Sargent’s distinctive preoccupation with portraits and his approach to the process of painting. Instead of relying solely on symbols or narrative, he shows sensitivity towards the beholder’s awareness of medium and process: his painterly logic precludes a purely illusionistic view. While Sargent denies the beholder access to the inner psyche of the sitters or access to imagined spaces beyond the surface, he does provide access to the physicality of the canvases and paper, access to the materials of the painted compositions, and access to the artist’s process.

In his 2000 review of the 1998 exhibition, John Singer Sargent, Christopher Capozzola asked, “But what can we say about Sargent’s work other than that it pleases us? Can we learn from the painter at this moment without participating in the romantic and mythologizing impulses of the return to loveliness?”[4] Fifteen years later, Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends encouraged visitors to set aside such romantic impulses, and to engage more deeply in Sargent’s discourses on performance and process.

While this exhibition did not preclude us from appreciating the pleasing aspects of Sargent’s portraiture, it refused to let us remain there, broadening the scope of conventional interpretation to reveal the risk-taking, experimental artist whose friendships were as diverse as his pigments. A patient viewer of Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends could be simultaneously dazzled by Sargent’s brushwork and aware of his skepticism towards portraiture’s precepts. And yet, for such active paintings and works on paper—defined by dazzling brushwork and dynamism—the passivity of the exhibition’s title was disappointing, and the most interesting themes of the exhibition—performance, identity, and the fraught conventions of representation—remained unacknowledged. Perhaps a future exhibition could investigate the semantics of his painting process, allowing viewers the chance to experience the surfaces of his portraiture as a discursive arena. Such queries could encourage further analysis of his material experimentation in tandem with his friendships.

The ultimate success of Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends will rest in its capacity to foment further study, catalyzing scholars to consider Sargent in new terms. While this exhibition may not revolutionize our understanding of Sargent’s prodigious oeuvre, it has certainly opened up new productive lines of inquiry into his role within a transnational creative community and reconsidered his disinclination to produce complacent portraiture.

Elizabeth W. Doe, Ph.D. Student

History of Art and Architecture

University of Virginia

ewd4nt[at]virginia.edu

I wish to thank Stephanie Herdrich at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for her valuable insights and assistance providing installation photographs. I am grateful also to Sarah Betzer and the editors at Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide for their helpful comments.

[1] See Alison Syme, A Touch of Blossom: John Singer Sargent and the Queer Flora of Fin-de Siècle Art (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2010), 142.

[2] Evan Charteris, John Sargent (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1927), 187.

[3] Letter from FitzWiliam Sargent to his brother. See David McCullough, The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 400.

[4] Christopher Capozzola, “The Man Who Illuminated the Gilded Age?” American Quarterly 52 (2000): 516.