The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

This article, based on recently discovered material in several archives, tells the story of the bronze doors of the Morgan Library.[1] It narrates the travel of the allegedly Renaissance bronze doors from their acquisition in Florence in 1901, to their brief sojourn in London before arriving in New York to adorn the principal façade of McKim, Mead & White’s building. This case study also addresses the attribution of the work to Thomas Waldo Story (1855–1915) and analyzes his position within the complex social microcosm of the art market in which the acquisition of J. Pierpont Morgan’s doors took place.

The Transaction of the Doors

On Friday, May 10, 1901, the New York attorney and financier William Salomon (1852–1919)[2] visited Florence in order to acquire art and decorative furnishings for his future mansion at 1020 Fifth Avenue, across the street from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Perhaps his most important appointment that day was a visit to the collections of the Florentine dealer Stefano Bardini (1836–1922).[3] Following an introduction to the Bardini Galleries in Piazza Mozzi, at some point in the shopping spree, the Philadelphian sculptor Albert Harnisch (1842–after 1918), then working for Bardini, escorted Salomon to Villa Marignolle (fig. 1).[4] Located in the hills south of the city and purchased by Bardini in 1891, Villa Marignolle was restructured over time and installed with a keen eye for the display of Italian fifteenth-century style art and decorative arts.[5] In the end, Salomon selected objects from the Villa, and probably also from the Galleries.

In addition to shopping for himself, Salomon was also shopping for the American financier and collector J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913). And, most incredibly, Salomon was shopping for art and decorative fittings for the future Morgan Library, which would be realized between 1902 and 1906 by the architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White.[6] Indeed, the two financiers, Salomon and Morgan, would have traveled in the same professional and social circles, and were likely friends, as they both enthusiastically collected art and decorative art.[7] Moreover, Salomon was surely privy to some of the earliest musings and ideas for the plan to build the Morgan Library because the very property for the library had been purchased by Morgan from Salomon in January 1900.[8]

Salomon’s visit to Bardini’s Galleries and Villa is documented by a small envelope bearing his name and the dates of what were, in all, three days of shopping.[9] The envelope contains several sheets of paper with descriptions and prices of objects in the handwriting of Albert Harnisch. Two of the lists are moderate in their ambition in terms of object and cost, whereas a third list, lacking a name, is for a far grander vision, that of Morgan for his library:

[In pencil; translated from Italian by the author]

| Gothic Column | £4,000 | |||

| fragment Roman column | £600 | |||

| ceramic door [sic] | £5,000 | |||

| fireplace mantle | £7,000 | |||

| large fireplace | £40,000 | |||

| fresco | £25,000 | |||

| [fresco] | £10,000 | |||

| Library door | £25,000 | |||

| 3 Doors | 50,000 | £150,000 | ||

| 50,000 | ||||

| 50,000 | ||||

| 2 gilded boxes | £25,000 | |||

| small bronze pin | £25,000 | |||

| door knocker | £3,000 | |||

Recent research has revealed that a bronze door, either the aforementioned “library door,” or one of the other three doors listed for 50,000 lire, was sent to London. By May of 1902, Morgan—apparently believing them to have been made in the fifteenth century in the style of Ghiberti—had the door shown to the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) with the hope of loaning it for exhibition. Records in the archive of the museum dated May 21, 1902 describe the door as having “bronze panels representing scenes in the life of Our Lord with border of fruits and flowers, birds and animals, etc. (portions of woodwork damaged).”[10] It was further acknowledged by Sir Joseph Henry Fitzhenry (1836–1913), collector and advisor to the museum,[11] who noted that the offer would be declined because,

These again are not of an interesting type and do not recommend themselves on account of striking artistic qualities either of design or execution, so that it would be inadvisable for the Museum to accept such works on loan. Indeed, considering the increased commercial value which objects acquire through being exhibited on loan at the Museum, which is thus assumed to place a sort of stamp of authenticity upon them, too great care can hardly be exercised in accepting objects upon loan.[12]

From South Kensington, the doors were sent to Durlacher Brothers,[13] on Old Bond Street, who in turn shipped them on behalf of Morgan to Duveen Brothers in New York City where they would remain until 1904.[14] In October 1904, McKim, Mead & White was informed by the William H. Jackson Company,[15] that it had examined “the wood and bronze doors now at Duveen Brothers, calculated for the front entrance doors for Morgan Library (fig. 2).” It further indicated that it was ready to install the doors, with “all of the necessary bronze and glass work complete, including the entire arrangement for hanging these doors, furnishing the new bronze transom bar with frames, trim, etc., including new bronze supports and hangings for the doors.”[16] And, by May 1905, in a McKim, Mead & White memorandum, the doors were noted as, “at entrance, bronze door of the Renaissance” (figs. 3–5).[17] Still, in 1914, the doors were described as “antique, of bronze, Italian in design.”[18] In 1966, when the Morgan Library and Annex received its designation as a New York City landmark, the doors were described as having been “ascribed to Italian craftsmen of the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, and are in the tradition of Ghiberti’s renowned doors, the Gates of Paradise on the east side of the Baptistery in Florence.”[19] In addition to the Gates of Paradise (fig. 6), a comparison can also be made with Ghiberti’s first set of bronze doors, now on the north side of the Florence Baptistery (fig. 7). The Morgan Library doors can be seen today, in situ (fig. 3), in the portico on the building’s 36th Street entrance (fig. 4).

The Attribution of the Doors to Waldo Story

In an altogether different scenario, the bronze doors of the Morgan Library have been attributed to Thomas Waldo Story (1855–1915; fig. 8)[20] and dated to circa 1906. In 2009, Kathleen Lawrence attempted to restore attention to Waldo as the forgotten son of William Wetmore Story (1819–95),[21] and to readdress the issue of the Morgan doors, categorizing them as the most significant of Waldo’s commissions for America and as “the final major work of Story’s career and one that is unappreciated and rarely recognized to be of Story’s making.”[22]

Thomas Waldo Story[23] was the son of the American sculptor from Boston, William Wetmore Story, who by 1856 had effectively relocated to Rome. Waldo was raised and trained in his father’s atelier, which occupied, together with the family’s apartments, some 20 rooms in Palazzo Barberini in the Via delle Quattro Fontane.[24] No doubt, Waldo lived in the long shadow of his father, who had achieved international repute as a sculptor, and as a socio-politically conscious transplant from Boston. The elder Story’s career was also bolstered by his many relationships with writers, among them, his biographer Henry James (1843–1916). Indeed, throughout his career, Waldo reaped benefits from his father’s social network.

Waldo included among his friends James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), who in 1887 succeeded in getting Waldo elected to the Society of British Artists.[25] He exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in London from 1882 until the gallery’s closure in 1890.[26] During the 1890s, Waldo completed several commissions for large-scale garden fountains and statuary, as well as for grand-scale interior decoration for prominent British clients, such as Lord Leopold Rothschild (1845–1917), William Waldorf Astor (1848–1919),[27] and Lord Randolph Henry Spencer Churchill (1849–95), the second son of the sixth Duke of Marlborough.[28]

The tax increase on imports of art, implemented by the United States Congress in the summer of 1883, had a lasting and devastating effect on artists working abroad; it would have grave consequences, as well, for American dealers,[29] and just as much for the recently wealthy American collectors eager to shop abroad. This was the primary reason that most of J. Pierpont Morgan’s numerous acquisitions of the 1890s were stored in London.[30] Indeed, it was Waldo’s father who led the campaign to repeal the increase, presenting more than once to Congress an impassioned petition signed by more than two dozen artists, including Albert Harnisch, Waldo Story, Edmonia Lewis (1844–1907), and Elihu Vedder (1836–1923).[31]

The 1880s and ’90s also saw escalating opportunities for public and private commissions in America. And, it is evident that by the turn of the century Waldo cast his eye abroad, traveling in 1901 to Newport and New York in order to drum up business.[32]

In February 1902, Waldo was among thirty-six artists who submitted a model in competition for the monument to Ulysses S. Grant to be erected in Washington.[33] At the time, the project was considered to be “the most important art project that had ever come before American sculptors and architects.”[34] Two finalists were chosen, and six others, including Waldo, each received a merit prize of $1,000.[35] In June of the same year, Waldo’s name was submitted for the competition for the Davis Arch Memorial in Richmond Virginia.[36] In less than a week, it was determined by the committee that they did not think Waldo could complete the project within the budget of $75,000, and they instead accepted the design of Louis A. Gudebrod (1872–1961), noting that he had the advantage of “the best masters, among them Augustus St. Gaudens, in New York and Jean Dampt, in Paris.”[37]

A Silent Record for the Doors and Their Attribution to Waldo

In a focused article promoting Waldo’s work to America, the Minneapolis Journal reported in 1906 that Waldo was providing works for Newport and that he was planning to open a studio in New York. The article discussed Waldo’s sculptural talent for portraiture, bas-relief, and grand-scale interior and garden decoration, mentioning some prominent clients, among them J. Pierpont Morgan’s sister, Mrs. Burns. Incredibly, there is no mention of the bronze doors on the Morgan Library.[38]

The first brief mention of the attribution of Mr. Morgan’s doors to Waldo Story appeared two years after Morgan’s death, in 1915, when they were listed in two of Waldo’s obituaries.[39] Owing to the lack of documentation in the papers of J. Pierpont Morgan, the attribution fell from the official record. According to the family of Waldo,[40] nothing existed in the family papers—the attribution was “family word of mouth.”[41]

With respect to material in the Morgan Archives, the provenance of these doors had been a mystery mainly for two reasons. First, it had been assumed that they were acquired after Charles McKim’s final plan for the building had begun to materialize circa 1903.[42] The Bardini archive evidence, however, effectively re-dates the transaction of the doors to May 1901. In part, the lack of record in the Morgan Archives was understandable, since many of Morgan’s European purchases prior to circa 1904 stayed in London until import duty loopholes were discovered (as, for example, at Mrs. Gardner’s museum, which allowed for public access to its treasures); much of the object documentation never made it to the archive in New York.[43] This situation remained until the arrival in 1905 of Morgan’s librarian—and then archivist—Bella da Costa Greene (1883–1950). However, working with a revised date of 1901 for the acquisition, the receipt for the doors’ arrival at Duveen’s in New York in November 1902 is now easily located in the Morgan Archives.[44]

Both Stanford White[45] and Charles McKim were longstanding, tremendously active clients of Bardini, and, indeed, the Bardini archive is rich in their correspondence and records of their transactions. Curiously, there is no evidence that either White or McKim knew anything about these purchases made by Salomon on behalf of Morgan. This in turn raises interesting questions, among them, whether the objects purchased in Florence initially informed the architectural early changes to the design of the building.

In addition, nothing on record indicates that Morgan knew Waldo had made his doors, which is odd especially since they knew each other, and probably fairly well. In 1867, Morgan’s partner Walter Hayes Burns (1838–97) married J. Pierpont Morgan’s sister, Mary Lyman Morgan (1844–1919), and by 1878 they moved to England where Burns continued the partnership.[46] Their country residence at North Mymms Park, near Hatfield, was the site of several commissions to Waldo Story, including, “the large gates, the loggia, hall and dining room.”[47] In August 1901, when McKim was soliciting support for the fledgling American Academy in Rome, at a time before he had first met J. Pierpont Morgan, McKim reached out to Waldo Story to capture Morgan’s interest in the Academy.[48] By November, and within the space of forty-eight hours, Waldo succeeded in enlisting Morgan’s support.[49] It is evident that Waldo had a relationship with Morgan well before this point, and indeed Waldo had known Charles McKim since the earliest years of the American Academy, when Waldo was appointed as a local member to the board.[50] Waldo’s relationship would continue with both McKim and Morgan, for in 1904, Waldo was in Rome and, on behalf of McKim, he was scouting porphyry and travertine for what would become the exquisite floor of the vestibule of the Morgan Library.[51]

At the time of the sale of the doors to Salomon, the sixty-five year old Bardini had become increasingly ill and increasingly difficult.[52] Though, what follows is a working hypothesis, it seems as though at least some in the group of his managers[53] sought to discredit him, driving business in their direction instead of his. This plan apparently took its actual shape in the transaction of the bronze doors which came from Bardini’s villa carrying the attribution of “style of Ghiberti,” which is also to say that the doors were branded as having been made in the fifteenth century. However, details given in an unpublished manuscript (Appendix B)[54] of one of Bardini’s managers, Riccardo Nobili (1859–1939),[55] suggest that Nobili purposefully passed on the intelligence to Fitzhenry that the doors were, in fact, modern. Nobili wrote,

In earlier days we are told that Mr. Morgan was attracted by the literary field, it was even said that he wrote very good lyrics and it is small wonder that this axiom finally led him to the real Art. And it is not strange either that some of his friends who claimed a certain experience of connoisseurship should have been his first advisers. . . . We cannot tell to what extent these friendly counsellors helped the enthusiastic newcomer but it is certainly a fact that a friendly advice given by people mostly belonging to the literary field, art critics, etc. . . . must bear the brunt of the responsibility of certain blunders attributed to Mr. Morgan. Such was the acquisition made in Italy in 1902 of the so-called Ghiberti’s bronze door, which Morgan bought upon the advice of an American friend,[56] an appreciated writer of Art; a dilettante as a connoisseur, and at the time Editor of one of the important New York dailies. The said gate was taken to London and deposited temporarily in the Kensington Museum. A friend who was employed in the Museum showed me this recent purchase of Pierpont Morgan Sr. It had been placed in a private room “for examination” before being exhibited publicly. It was a large double door, an oak frame covered with bas-reliefs in bronze—Biblical subjects if I remember rightly—in the manner of Ghiberti. I had already seen a door of the same style in Lord Mexborough’s villa at Maiano,[57] near Florence. That one was an authentic fake though of beautiful workmanship which might easily deceive. So I concluded: “Since that one is false, this one is false also.” My “discovery” had no more merit than that of a cashier who recognizes a forged signature. After carefully examining Pierpont Morgan’s door, I said to the friend: “it is beautiful, old chap, but modern.” My words made pandemonium break loose!

At the time, Pierpont Morgan was away from London. Sir Fitzhenry, his alter ego, came to see me and begged me to give him the proofs of my rash judgment. Not wishing to give him the chief reason for my opinion, I told him briefly the results of my examination. I noted that the gilding was not of the antique system, that is, gold amalgamated with mercury; that some grains of sand left by the mould when it cooled after casting were lodged in the cavities, that the patina of the angles imitating the wear of centuries was not transparent enough, or to use a technical term, it was “dull.” The work was stupendous, the price—50,000 lire—moderate, and Pierpont Morgan, being a lover of beauty, decided to keep it. It was proved later that the bronze door was cast at Pistoia, a very few years before this clamorous sale. One thing might be said, that this fine door was fully worth the price paid by Mr. Morgan, but, of course, if it had been a question of a genuine Ghiberti, half a million would hardly have been enough.

In this scenario, Nobili functioned as the hero and tipped off Fitzhenry that the doors were modern. In turn, this would have had the effect of disparaging the business practices of Bardini, and just as much, it served to advertise Nobili’s expertise. It seems as though the plan was at least partially successful insofar as Nobili, Harnisch, and Story all turned up in New York shortly thereafter, and they can all be documented as having various dealings with J. Pierpont Morgan. As a further corroboration, the Bardini archive conspicuously lacks evidence of any direct dealings whatsoever between Bardini and J. P. Morgan. For reasons still unknown, Bardini seems to have allowed the managers to deal directly with Morgan, although the reason may have been one as simple as a language barrier.

In the end though, they may have outsmarted themselves, since Nobili, Harnisch, and Story could hardly have admitted to their involvement with the doors. In any case, the current was against them, since by this time the wealthy art-collecting, mansion-building Americans were changing their taste from Roman-trained American sculptural production (both modern and works pretending to be from the Renaissance) to work inspired by the École des Beaux Arts and channeled into American mainstream architectural practice via the curriculum of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[58] The younger generation of artists working in its tradition were out in full force competing for commissions.[59] Thus, among the first decorative decisions for the Morgan Library were the imported “Italian Renaissance” bronze doors and the Roman porphyry vestibule floor, whereas the lunette and putti above the bronze doors were made by Andrew O’Connor (1874–1941),[60] and the façade reliefs were executed by Adolph Weinman (1870–1952).[61] It was a similar situation with respect to the artists hired by McKim for much of the interior adornment, which was executed by artists with ties to Paris: the ceiling paintings of the rotunda and the library were executed in 1904 by Harry Siddons Mowbray (1858–1928);[62] the French-born James Wall Finn (1866–1913) combined old parts from Florence with new parts to create the painted “distressed” look of the wood coffered ceiling in the study.[63]

What About the Attribution to Waldo?

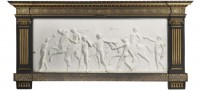

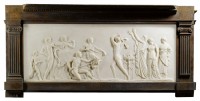

With respect to the attribution of J. Pierpont Morgan’s doors to Waldo Story, one can only come so close. First, there is the issue of imagining Waldo’s winsome, vaguely neoclassical style transposed into the medium of bronze. Second, there is the issue of either anachronic stylistic appropriation, or outright intent to deceive. Despite these caveats, a reasonable stylistic comparison can be made with two pair of marble reliefs depicting Paris and Helen and The Horse Race in the Isthmian Games signed and dated by Waldo in 1882. One pair (figs. 9, 10) was exhibited in the summer of 1882 at the Grosvenor Gallery, London;[64] they were last sold by Sotheby’s in New York in 2006 and are presently in a private collection in Switzerland.[65] In 2008, another pair (figs. 11, 12) was sold at Sotheby’s London, and these are currently in a private collection in Massachusetts.[66] Though much smaller in scale, they have been compared to the relief decoration executed by Waldo for Rothschild’s Billiard Room at Tring Park.[67] They share with the Morgan doors a certain figural style, in particular with respect to the vaguely choreographic outstretched arms (figs. 9, 11). More generally, the treatment of the relief surface is the same, especially in the abrupt mitigation of the mid-distance. And, despite the fact the doors were transacted as in the style of Ghiberti, that they could be considered even remotely fifteenth-century Florentine is out of the question.[68]

The doors are not signed or dated, nor is there any extant archival material to suggest that the doors bought by Morgan were knowingly commissioned from Waldo. Furthermore, Riccardo Nobili’s essay suggests that Morgan was duped into believing the doors were Renaissance; at the same time there is the obvious omission on the part of Nobili to identify the real author of the doors. To be sure, as a high-level manager for the Bardini business, there is no doubt that Nobili would have known the backstory of the doors. What remains to be done is to connect the dots from Waldo Story in Rome to Bardini’s Villa Marignolle in Florence. The degrees of separation between Waldo and Florence are actually very few. On the 6th of February 1876, his younger sister, Edith, married the Florentine Marchese Simone Peruzzi de’ Medici,[69] whose family enjoyed ancient noble lineage. The marchese owned a summer home at the Lago di Vallombrosa in the countryside of Florence, which was frequented by members of the Story family. Indeed, it would be here that the elder William Wetmore would retire and eventually die.[70] But it is possible to connect more dots between Waldo and Bardini & Co., and these may be found within the relationship between Waldo and Albert Harnisch.

Albert E. Harnisch was born in Philadelphia in 1842 and trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.[71] By 1869, he relocated to Rome. In 1871, it was reported in the Art Journal that he had a studio in the Via Margutta, and that the “young American sculptor” was already enjoying success.[72] The following year he rented a studio in the Via Sistina, 58B.[73] From 1871 until 1885, Harnisch rented a room from Anne Brewster on the via delle Quattro Fontane, 107B.[74] It was here that Brewster conducted her weekly salons, which included her literary, musician, and artist friends, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, James Russell Lowell, Franz Liszt, Harriet Hosmer, and Elihu Vedder.[75] Closest among these friends were William Wetmore Story and his wife Emelyn,[76] whose apartments in the Palazzo Barberini were less than two blocks away. Thus, from at least the age of seventeen, Waldo Story would have known Albert Harnisch quite well.

In 1879, Harnisch competed for and won the commission for the Monument to John Calhoun destined for Charleston, South Carolina. By 1885, parts of it were cast in the public foundry in Rome, where it already met with poor reception.[77] The reception did not improve when it was shipped across the Atlantic and dedicated in 1887; by circa 1894, it was already dismantled and replaced with another monument.[78] Indeed, Harnisch’s experience might be seen as the harbinger of Waldo Story’s own less-than-spectacular career in America. Immediately following what had to have been a devastating career setback, Harnisch packed himself up, evidently temporarily leaving behind his bride of two years, and relocated to Florence. Here, he registered himself as domiciled at Bardini’s property.[79] Harnisch worked for Bardini, certainly through 1903, and probably through 1909, and perhaps even longer as they were in touch up until the year before Bardini died.[80] By 1901, at the time the doors were sold to Salomon, Harnisch was among the three top senior managers working for Bardini. The doors could have easily been brought from Rome to Florence—they are actually composed of bronze panels and ornament[81] attached to wood—and installed in Villa Marignolle, possibly on the exterior chapel (fig. 1), where they would be shown to Salomon by Harnisch. Based on his friendship with Waldo, and the fact of Waldo’s knowledge of Morgan, and presumably his taste, a scenario presents itself wherein Waldo, in effect, made the doors to order. Waldo branded the doors with a pair Medici heraldic devices (figs. 5, 13, 14), situating them prominently above the upper narrative scenes. This was a marketing strategy, which subtly drew upon the relationship between the Golden Age Renaissance Florentine banker, Lorenzo the Magnificent de’ Medici, and the Gilded Age banker par excellence, J. Pierpont Morgan.

Additional archival material suggests the presence of a tangled web of dealings, wherein it is difficult as yet to fully understand the real roles of the many men who were trying to lure Morgan’s millions. Included among them was Fitzhenry, functioning as advisor to Morgan as well as to the London museums; in the case of the bronze doors, he emerges as a bit of a double agent. In a letter to Nobili on July 1, 1902, Fitzhenry wrote,

Dear Friend,

I await with impatience your report on the “Bronze Doors” you believe to be fake. If you can present indisputable proof, this will benefit you in your own future dealings.

I still hope to persuade Mr. M[organ] to consider your busts and stuff [textiles], but he is “most vexed” at present by what is going on. Mr. M has seen your much talked-of Bronze[82] decried at the Museum—something that had never happened before.

He paid Durlacher the £6000 you demanded for the Bronze. Everyone finds your price exaggerated, even those who admire it; and if it hadn’t been for my determination to destroy this cabal (against you) I would not have authorized Durlacher to go above 100,000 frs – £4000! Most good judges thought £2000 (50,000 francs) a good price to pay! Anyway, it’s done now.[83] I hope to be in Florence & to make a quiet tour of the whole of Umbria (this winter). So fix a price the museum can afford for the early Maiolica it wishes to have. I trust in the King’s recovery and in the resulting rise in value of “art objects.”[84]

Another colorful character is one Maurice de Bosdari (1856–1943) who was buying objects from Bardini and working with Fitzhenry to sell them to Morgan.[85] One case involved the transaction of a small bronze statuette of Ganymede which Bosdari and Fitzhenry sold to J. P. Morgan as by Cellini.[86] Bosdari retained the check from Morgan from which he counterfeited Morgan’s signature on more checks. On February 11, 1903, Morgan received a report forged checks, whereupon a warrant was issued.[87] When found out, Bosdari went on the lam in 1903[88]—but only sort of—from 1913, under the assumed name of Bremont, he worked for Thomas Agnew and Sons Ltd[89] as an agent and mediator.[90] He was finally arrested in 1917[91] and, ironically, it was J. Pierpont Morgan’s son who placed the decisive signature on the petition circulated by the London dealers to win his release from jail.[92]

If Bosdari was sly, Bardini’s managers were more so, and they succeeded in attracting Morgan’s attention.[93] This was possible since Riccardo Nobili knew J. Pierpont Morgan’s advisor Fitzhenry, and he also had strong network ties to New York.[94] Although it is too soon to be certain, it seems that Nobili and Albert Harnisch, together with Waldo Story, circumvented Stanford White and Charles McKim, and likely also Stefano Bardini, in an attempt to garner what they thought would be an enormously profitable relationship with J. Pierpont Morgan and his soon to be built Morgan Library.

Appendix A, Formal Description: The Morgan Library Bronze Doors

The doors are composed of ten individual bronze panels set onto constructed wooden doors; the three pairs of central panels are narrative and framed by decorative borders, also in bronze, consisting of animals, fruit, and vegetal garland which ascends from two pair of vases in the corners of the lowest narrative register (fig. 5). The garland terminates at the top center of each door with baroque escutcheons bearing the heraldic device of the Medici, with six palle. At each of the corners of the panels are small rosettes. A pair of smaller rectangular horizontal panels runs on both the top and bottom of the doors (figs. 15, 16). On the top left is depicted what looks to be the Holy Spirit as a dove, situated in the heavens, emitting rays of light. On the right, also in the heavens, indicated by swirling curls of clouds, is represented a bearded God the Father whose right hand is raised in benediction. At the bottom of the doors are two rectangular panels, each depicting heavily draped semi-reclining bearded male figures (fig. 16). The one on the left, apparently a prophet, holds a scroll, though it more resembles a banderole. The figure on the right looks downward and gesticulates a blessing with a slightly raised right arm. Of the six narrative panels, the top and bottom pairs are rectangular and vertically oriented; the two at the center are square.

The narrative order of the panels is decidedly eccentric in their positioning within the overall program. Beginning at the center and reading from right to left is the scene of the Birth of the Baptist, or possibly the Birth of the Virgin (fig. 17); it seems based on a conflation of aspects from the scene of the Birth of the Baptist and the scene of the Birth of the Virgin by Ghirlandaio in the Tornabuoni Chapel in Santa Maria Novella, Florence (1486–90). On the left of the panel, in low relief, a (not old) woman reclines in a canopy bed, with curtains drawn open at the four corners; the face of another woman can be seen behind the bed. Three women in higher relief occupy the center of the composition; they bare a vessel and basket which holds a baby. The panel on the left depicts the Annunciation (fig. 18); the Virgin kneels at a pew, with left hand to her breast, while gesticulating out from the door with her upturned right palm. She gazes across to the genuflecting Archangel Gabriel, with long flowing hair, whose right hand is raised, and in whose left hand are lilies; between them is a vase of lilies. The figures are in high relief, whereas the background is treated in very low relief. The space is divided; that of the Virgin is an interior, with a massive fireplace at the left, and possibly a window frame at the right. Two putti hover atop. Gabriel occupies a seemingly exterior space, framed at the left by a loggia, which terminates at the back, opening to a distant view. In the center at both the top and the bottom of the horizontally running decorative borders around these two panels are small eagles, with outstretched wings perched within a circle.

The narrative continues on the upper right of the doors with a scene of the Adoration of the Magi (fig. 13), depicted kneeling in high relief in the left foreground. Seated on rocks, the Virgin displays the infant; standing behind her, under a manger frame, is Joseph. On the left, in low relief is depicted a mountainous landscape, with a bridge in the mid distance. Winged angels, holding a long banderole populate the heavens above. The narrative—abruptly—continues in the panel on the left, which depicts the Flagellation of Christ (fig. 14). With arms bound behind, Christ sits on what looks to be a bell-shaped object. Amidst a flurry of drapery, two men participate in the scene. Figures, among them probably Pontius Pilate, are huddled under the loggia in the background; in the left foreground are a helmet, shield and sword.

The bottom two panels conclude the sequence. On the left is the Carrying of the Cross (fig. 19); Christ has slumped under the weight of the cross which is being drawn by a Roman soldier. At the lower right corner, a seated figure supports the other end of the cross; his left draped leg with bent knee projects out and down from the rocky plinth of the scene. In the mid distance, stands a cloaked figure with clasped hands, and to the right is another soldier on horseback holding a spear. More spears and a flag are in low relief behind him. The last scene on the lower right depicts the Lamentation of Christ (fig. 20) whose prone body is supported in the lap of the Virgin. Two other figures are pulling the shroud onto the body, while a third stands at the left, with hands clasped in prayer. In very low relief in the background, a mountain ridge rises to the upper right; upon it are visible three empty crosses. In the sky hovers a winged angel carrying a palm frond.

The perspectival adjustments in the individual panels are in accordance with a viewer standing before the doors. That is, the upper panels are rendered so as to be seen from below, whereas the lower panels are treated so as to be seen from above.

Thus, according to the placement of the panels, the viewer is expected to read them from center, right to left, then at the top from right to left, and at the bottom, from left to right. Not only is the placement odd, but so are the choices of scenes represented. The relationship to Ghiberti is evocative in the ornamental additions of garland and rosettes, and in the way the background of the scenes is treated in very low schiacciato relief, as well as in the placement of reclining figures at the bottom. Overall, the doors are evocative of Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise (ca. 1425–52; fig. 6)[95] on the east side of the Baptistery in Florence.[96] The relationship of the figures to the frame compares to Ghiberti’s first set of bronze doors (ca. 1404–24; fig. 7) now on the north side of the Baptistery. The small eagles depend from those by Ghiberti on the left and right of the predella of the niche that houses his St. John the Baptist on Orsanmichele in Florence.[97] However, the style is not Florentine, and this produces a visual sensation that is on the overall quite jarring.

Appendix B: Riccardo Nobili’s Essay on J. Pierpont Morgan

Typescript, “Reminiscences of the late Pierpont Morgan Sr. as an art collector,” Box 1, Grace Nobili Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, MA.[98]

Reminiscences of the late Pierpont Morgan Sr. as an art collector

Very few in the world of Art collectors have paid their experience at such high price, as did the late Pierpont Morgan Sr. in his curriculum as an art amateur. Any other less persistent, in all probability would have given up the job before the desired end. Yet this indefatigable millionaire not only persisted in swimming against the tide but finally gained what he wished as a man of taste and eclectic disposition and gathered a multiform art collection which ranges from miniature to valuable paintings, from classic sculptures to small bronzes and plaquettes.

According to his taste, Mr. Morgan carried on his work as collector with the most liberal view, extending his choice to decorative objects even if some of these ornaments had no tradition, no genuine family tree.

Entering into his train of thought and for the sake of an explanation, one must admit that Mr. Morgan, or possibly his architects, must have been facing this particular dilemma: Considering that it was a question of enriching the walls of the museum—say with ornamented doors or artistic chimney pieces and so forth—was it better to insist on genuinity, integrity, namely the Simon Pure objects from top to bottom, or winking an eye and accepting objects of and ornaments of the above character either largely restored and composed of heterogeneous parts admirably assembled, more harmoniously adapted. When on thinks that the most genuine art piece taken out of the wall of its birthplace and transferred into a different art climate is always a misfit, we are not surprised that the architects of Mr. Morgan or his advisers for his library, for the sake of beauty, did away with the pedantic view.

In fact, Mr. Morgan or his architects, in this special case must have been of the opinion of one of the most witty curators of the Kensington Museum, the late Mr. Armstrong[99] who, when an object of suspicious character was offered to the Museum, used to answer whimsically: “My dear, it is too beautiful to be an antique.”

The chimneypieces, for instance, that adorn Mr. Morgan’s library are mostly antique even if some of the parts do not belong to the original chimney. But as a fact, they are so well composed, so well arranged and rendered so beautiful through these manipulations as to justify even in this case Mr. Armstrong’s remark. Speaking of their manipulations, one of the best of the said chimneys for the number and variation of the pieces that composed it might justify carving in the blank escutcheon the motto “E pluribus unum.”

The most important chimneypiece of the Morgan collection, a real chef-d’oeuvre of composition serves to point how different pieces of various origin with taste and talent can be turned into a most admirable harmonious totality. This art piece in the style of the XVth century has the following origin: the entablature, the most important part of it is of a stone called “Lavagnino,” a rare type of stone that, in olden times was found in a quarry in Fiesole, near Florence. One quarter of the entablature is modern work admirably carved by a Venetian artist called De Pol. The genuine part of the entablature was bought in Venice in the shop of Giuponi, a stone carver who kept this treasure in a depository in Campo Santa Maria del Giglio.

The entablature of this chimney is enriched by following bas-reliefs: in the center is an escutcheon with no coat of arms, the said shield of the form called “testa di cavallo” (horse’s head) has no heraldic emblems. In olden times, chimneypieces were kept ready for marriage occasions to receive the quartered coats of arms of the bridegroom and the bride. According to the fashion of the time, the shield was encircled by a garland of palms with a cupid on either side. At the right and left sides of the entablature are vases with conventional foliage and carved roses. The upper cornice of the entablature is of the usual type of moulding with egg friezes. The stone of the cornice is of a different grain, possibly from a Verona quarry and of a slightly reddish tonality. Before leaving the entablature let me say that to my knowledge the small modern part of the entablature, in order to be a perfect match of the genuine portion, would have needed the sacrifice of an old chimneypiece of the epoch. We have said that Lavagnino does not exist anymore; a small piece, considering the rarity of this material might be estimated at about two thousand lires. . . .

The brackets and the two pillars are evidently antique but not utterly in keeping with the rest, either for age or style. The pilasters (candelabra) ornamented with bas-reliefs of pine, poppies and foliage is a work at least fifty years younger than the rest. The two brackets seem to be handsomely hyphening the upper part of the candelabra, but are however too projecting to belong logically to the superior part of the chimney.

It is to be noted that the entablature has been left with the original line so that the demarcation between the antique and the modern part rendered visible the division line with a crack from top to bottom. When this chimneypiece reached New York and was mounted, for a last inspection before being transferred to Mr. Morgan’s library, Mr. Mac Kim suggested filling the crack and thus obliterating every sign of it. Noting my surprise, he remarked with his whimsical smile: “You see, Mr. Morgan does not like cracks. What is the use of advertising one in this chimney-piece?” So I spent the morning in re-mending the crack, filling it with a composition of Styrian silicate and ground stone.

When the work was finished, I stood contemplating the beautiful chimneypiece and became convinced that Mr. Mac Kim was right as an artist and as an architect. Decorative art means to obtain a given effect and all helps are legitimate to this end. Means do no concern the public any more than that the public should be ushered behind the scene into the mystery of stage effects.

Among the other chimneypieces that Mr. Mac Kim thought fit to modify, is N.2, which, originally had impossible brackets of Byzantine character; Mr. Mac Kim rebelled against such an anachronism and replaced it by two peacocks, with simpler modern brackets more in keeping with the rest. This change, as the others suggested for the different chimneys was done for art’s sake and with Mr. Morgan’s consent.

In the same spirit of adaptation, another large chimney of Gothic style which had a big marble hood, too bare to harmonize with the ornamental parts of the rest, was carved with rich foliage by a modern artist. Scandalmongers can look in vain into this matter since the work was prospected by the architects and approved by Mr. Morgan. As for the antiquarian who sold the art pieces, he had related the true story of the chimneypieces to Mr. Morgan; moreover, as it was impossible to find in America an artist who could imitate antiques, this eminent antiquarian supplied and shipped to America the required parts.

We have stated at the beginning of this article that very few collectors had paid their apprenticeship at such a high price as Mr. Morgan did, but we may add that very few profited as he did by the lessons. I do not believe that Mr. Morgan as a collector had so early a start as Mr. Quincy Shaw, a financier like Mr. Morgan and one of the best connoisseurs in America.

In earlier days was are told that Mr. Morgan was attracted by the literary field, it was even said that he wrote very good lyrics and it is small wonder that this axiom finally led him to the real Art. And it is not strange either that some of his friends who claimed a certain experience of connoisseurship should have been his first advisers. . . . We cannot tell to what extent these friendly counsellors helped the enthusiastic newcomer but it is certainly a fact that a friendly advice given by people mostly belonging to the literary field, art critics, etc. . . must bear the brunt of the responsibility of certain blunders attributed to Mr. Morgan. Such was the acquisition made in Italy in 1902 of the so-called Ghiberti’s bronze door, which Morgan bought upon the advice of an American friend,[100] an appreciated writer of Art; a dilettante as a connoisseur, and at the time Editor of one of the important New York dailies. The said gate was taken to London and deposited temporarily in the Kensington Museum. A friend who was employed in the Museum showed me this recent purchase of Pierpont Morgan sr. It had been placed in a private room “for examination” before being exhibited publicly. It was a large double door, an oak frame covered with bas-reliefs in bronze—Biblical subjects if I remember rightly—in the manner of Ghiberti. I had already seen a door of the same style in Lord Mexborough’s villa at Maiano,[101] near Florence. That one was an authentic fake though of beautiful workmanship which might easily deceive. So I concluded: “Since that one is false, this one is false also.” My “discovery” had no more merit than that of a cashier who recognizes a forged signature. After carefully examining Pierpont Morgan’s door, I said to the friend: “it is beautiful, old chap, but modern.” My words made pandemonium break loose!

At the time, Pierpont Morgan was away from London. Sir Fitzhenry, his alter ego, came to see me and begged me to give him the proofs of my rash judgment. Not wishing to give him the chief reason for my opinion, I told him briefly the results of my examination. I noted that the gilding was not of the antique system, that is, gold amalgamated with mercury; that some grains of sand left by the mould when it cooled after casting were lodged in the cavities, that the patina of the angles imitating the wear of centuries was not transparent enough, or to use a technical term, it was “dull.” The work was stupendous, the price—50,000 lire—moderate, and Pierpont Morgan, being a lover of beauty, decided to keep it. It was proved later that the bronze door was cast at Pistoia, a very few years before this clamorous sale. One think might be said, that this fine door was fully worth the price paid by Mr. Morgan, but, of course, if it had been a question of a genuine Ghiberti, half a million would hardly have been enough. Speaking of fakes, it is better, in certain cases to call them “imitations” because it is an art in itself, these artists do not fake, they imitate and interpret. I may say that this matter is a game which has been going on for centuries. My book “The Gentle Art of Faking” (falsifications in Art from the times of the Old Romans, up to the present day) is called the “Bible of the Antiquarians” and is intended as a guide for the unwary but I don’t think it will succeed in putting neophytes on their guard. They all think they are called to this art but few have a real desire to search and learn. Hoaxing is on the increase, it was so yesterday, it will be so tomorrow, in centuries and centuries.

Real genuine experts have however never been wanting and they are not wanting today, there are persons who recognize and discourage the incompetent as did Mannheim[102], an old antiquarian of the Place Vendome in Paris, a first rate connoisseur and hater of dilettantism. Every time a presumptuous collector came to ask his help regarding some great hoax, he would say: “I regret, Monsieur, but I am not the policeman of curiosities.”

Learning, practice and flair are necessary to become a collector. The first is helpful, conditionally even to the point of causing disasters, the second is never sufficient if not combined with the third. It sounds like a charade but this for me is the threefold equipment of the art of connoisseur. In short, as you see, the most dangerous is learning. Its blunders are incredible. I remember this episode. One day a painter, at Dijon, saw a chipped pot with four letters engraved on it in Roman characters. He bought it for a few sous, took it home and placed it on a shelf in his studio. A writer on Roman subjects came in, read the initials: M.J.D.D., thought for a moment and exclaimed: Good Heavens! This is a Gaelic Roman votive vase! The letters stand for “Magnus Jovi Deorum Dei.”

The learned scholar was preparing a repost to present to some Academy when an old model entered the studio, caught sight of the pot and said: “We ate that mustard when I was a boy.” “Mustard,” cried the artist, “then what are those letters?” “The initials of the firm: ‘Moutarde Jaune de Dijon.’”

Practice is the most necessary thing; as a youth, I visited galleries and collections without troubling about names, to learn to recognize the various types of art and various personalities. Perhaps my passion for fake had been a method of study. Just as the cashier of a bank studies false notes so as to better recognize the genuine ones.

As it often happens, by chance I was in London when an antiquarian friend asked me to take a precious ancient steel chiseled gun rest to Baron Nathaniel Rothschild,[103] who lived in a fine palace in Vienna and wished to buy the antique. The Baron received me with his usual courtesy and showed me his magnificent collection of arms. In the course of conversation, he asked me if the gun rest was by Cellini, as he had been told. I replied that I thought it was by Negroli, a celebrated engraver of the Milanese school. At first my scanty knowledge of arms consisted in having read Hoepli’s and Demmin’s manuals. The Baron thought I was a connoisseur and wished to test me, saying he had received two swords and would like my opinion on them. The beautiful swords lay before me and I gazed at them in embarrassment. Presently the Baron warned me: “Take care! One of them is a fake.” I confess I felt a shiver down my spine, but as an old fencer, the idea came to me to choose the plainer, the one I should have liked to handle, a Quattrocento sword of marvelous lines. “This one,” I said.

I was right! Perhaps it was not a chance; something urged me it might have been intuition.

“Well done,” said the Baron, “many have been taken in,” he added.

To return to Pierpont Morgan Sr., his sad experiences were chiefly due to his friends in whom he believed implicitly. Another would-be trouvailles was acquired owing to the advice of a French writer to whom the history of art owes a great deal, and proves that this adviser and celebrated writer had deluded himself in thinking that writing on Art and connoisseurship were identical, as if writing the history of the violin should entitle the author to call himself a violinist! The piece in question was a carved glass bowl attributed to Valerio Vicentino, but was in fact one of the most marvelous imitations of this esteemed artist of the XVIth century.

These examples serve to show how in the field of art it is easy to equivocate between learning and practical knowledge. But for Mr. Morgan’s luck, these counsellors were few and, in his growing experience he learned how to pick up his “animicustus,” one of these being Mr. Mannheim who was a great friend of Mr. Morgan and consented to be the expert for this client of choice.

Other renowned experts of real value joined the entourage of Mr. Morgan and a new atmosphere was felt; at this time, a bank collector was very much like an old banker of the Renaissance, Lorenzo dei Medici, who learned, like an alert hunter, the wisdom of having hounds in every country. Constant practice, open-eyed assistance, natural artistic bent finally ushered Mr. Morgan into connoisseurship, the Promised Land was reached.

One may find the result not only in his magnificent collection, but in the tasteful setting of the different rooms the proper ambient air so happily created. Certainly, as a Connoisseur, more especially in painting, one would search in vain for the fine qualities of another Banker, a colleague, one might say Mr. Quincy Shaw[104] of Boston, but there ware bankers and bankers, and the two experiences could hardly be compared, for, while Mr. Morgan, a buoyant youth, was neatly scanning the syllables of hi lyric poetical form that never saw the light (though according to his friends fully deserved it) Mr. Quincy Shaw was already given to the passion of Renaissance art that so nobly characterized his Collection.

If these two careers represent the fact that Art and mathematics, one might say logosmography, can sometimes trot along side by side in life under a common Master, the case of these two Bankers, is somewhat inverted, as do Quincy Shaw gained his experience grain by grain, through systematic progress from early years, while Morgan through his eclecticism however blessed, gained it in later times through the metamorphosis of a Poet, I dare to say, a dreamer. In his newly awakened passion for Art, he leapt, fully armed by courage, to reach the Promised Land, and undertook to swim through the ocean where plenty of sharks were awaiting his passage; this is really the heroic period of the great Collector Mr. Morgan. Either he really ignored the existence of possible pitfalls or had never known the sad history of a Millionaire Collector, a man of taste also, banker like himself, the banker Nathaniel Rothschild. When it was known that Mr. Rothschild was about to undertake a trip in the Orient to eventually buy real Tanagra statuettes (to be sure, not the ones traded in Rue du Bac) all the sharks of this deceitful ocean, travelled to the oriental border of the Mediterranean, and became amphibious, arriving at the spot where Mr. Rothschild was expected, in due time, ready to show him some of the art of Rue du Bac, affording the plutocrat at the same time the pleasure of unearthing himself the desired Tanagra statuettes.

To return to Mr. Morgan, this eclectic collector of Art in organizing his Art Gallery did not follow the present mania which claims that objects should be classified in series as shells or botanical products. Here personality is respected and not sacrificed to study, moreover nothing is granted here to the cherished hobby of erudition.

I repeat again that though Mr. Morgan was not a great collector, he was a collector of taste; and through taste, he acquired experience.

Now I will end with an anecdote: Years ago, accompanied by Sir Fitzhenry, a friend and alter ego of Mr. Morgan, I had the privilege of visiting Mr. Morgan’s mansion at No. 10 Queen’s Gate. It was then enriched by objects of Art placed here and there casually. I admired many beautiful and curious things, for instance the picture of a young girl by Romney next to a photograph of an elderly lady basking in the sun of an English garden, bearing the scantiest resemblance to the fifteen, unrecognizable but for a line written on the photograph: “Dear Mr. Morgan, you bought the original, here is the last edition.”

After seeing the wonderful collection of miniatures, china and bibelots, we were going down the stairs when I happened to notice on the windowsill, an incongruous collection of china puppets, and other animals of no particular mark or value.

Sir Fitzhenry seeing my puzzled expression said in an almost apologetic way: “That is a little collection gathered by Mr. Morgan’s mother, it was been left there, just as she placed it.” Call me sentimental, if you like, but I was moved. The marvels that I had seen paled in the presence of this innocent collection of little souvenirs left untouched for years, as an eloquent altar of filial love.

Florence, Italy.

1930

Riccardo Nobili

This material is part of a much larger project regarding the business and family of Stefano Bardini, which has captivated me since 2011. I have occupied myself with the mostly unstudied material in the Archivio Storico Eredità Bardini in Florence (hereafter referred to as ASEB) and the Archivio Fotografico Eredità Bardini, also in Florence, hereafter referred to as (AFEB). The material has only recently been preliminarily processed, and it will be quite some time before it will be catalogued so as to be truly usable for scholars. I have to date consulted more than 70,000 items and this is but a fraction of what exists. Both the ASEB and AFEB are under the jurisdiction of the state and, in particular, the Soprintendente Polo Museale Toscano. I am immensely grateful to Stefano Casciu and Cristina Gnoni for their unflagging generosity, interest in the project, and willingness to collaborate. In addition, I owe a huge debt to Stefano Tasselli, whose understanding of the world of Bardini is unmatched; I have learned so much from him. I am also grateful to the Columbia University Libraries, the Frick Art Reference Library, the Morgan Library, the New York Historical Society, and the Berlin Museum and Zentralarchiv for their incredible assistance in so many areas. Likewise, this project continues to move forward thanks to support from the Frick Center for the History of Collecting, the American Philosophical Society, CASVA, and the International Scholarship Programme at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Preußischer Kulturbesitz, and the Samuel H. Kress and Leon Levy Foundations. I must thank in particular Jeremy Boudreau, Denise Budd, Henry Keazor, Jacki Musacchio, Kerri Pfister, Paul Tucker, and Janet Whitmore for their friendship, help, and thoughts throughout. I have also benefited from ongoing conversations with my students and with my younger colleagues, including Patrizia Cappellini, Tina Öcal, Giuseppe Rizzo, and Joanna Smalcerz. With respect to the Morgan doors, special thanks go to my friends and colleagues at the Morgan Library, in particular, Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator; Christine Nelson, Drue Heinz Curator; and John Vincler, Head of Reader Services. They have been enthusiastic and indispensable every step of the way.

All translations are by the author unless otherwise indicated.

[1] For my detailed description of the doors, see Appendix A.

[2] Various short biographical sketches of Salomon have been published, among which, see Bankers’ Magazine 115 (1899): 720–21. For his obituary, see “William Salomon, Banker, is Dead,” New York Times, December 15, 1919, 15. In 1923, Salomon’s house and contents were to be sold. For the contents, see American Art Association, The Palatial Mansion of the Late William Salomon (New York: American Art Association, 1923). For the Salomon auction records, see Boxes 5 & 6, American Art Association Records, The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York. I wish to thank Sally Brazil for calling my attention to this material. Additional material is to be found at American Art Association records, circa 1853–1929, bulk 1885–1922, 1.3; Estate Inventory and Appraisals, circa 1908-circa 1921, Box 2, Folder 31 and 9.6; Auction Records, 1884–1911, Box 17, Folder 71, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. The house failed to sell and was later demolished. By 1925, construction of a “new 100 per cent co-operative,” thirteen-story building was underway, and Samuel H. Kress had purchased its duplex penthouse, at the time dubbed “the House in the Sky.” See “Suite on Fifth Avenue Sold for $150,000,” New York Herald Tribune, May 26, 1925, 29.

[3] Almost all of the literature on Bardini is in Italian and stems from the archival material held by the city of Florence; it concerns itself primarily with the collection of the Museo Bardini. The biographical details of the man and his business have been thus far largely elusive. A recent contribution resulted from an exhibition in 2013 at Villa Bardini which explored the relationship between the Parisian collectors Edouard André and his wife, a painter, Nélie Jacquemart and Bardini. The dealer, the collectors, and their objects were united with a complement of rich archival material, for which see Marilena Tamassia, Musée Jacquemart-André and Museo Bardini, Rinascimento da Firenze a Parigi andata e ritorno: I tesori del Museo Jacquemart-André tornano a casa: Botticelli, Donatello, Mantegna, Paolo Uccello (Florence: Polistampa, 2013). Another fairly recent publication is admirable for its examination of Bardini’s relationship with Wilhelm Bode, and secondarily, with Julius Myer, on the basis of meticulous study of the Bode and Meyer papers held by the Berlin Zentralarchiv, for which see Valerie Niemeyer Chini, ed., Stefano Bardini e Wilhelm Bode: Mercanti e connoisseur fra Ottocento e Novecento (Florence: Polistampa, 2009). The main body of literature is as follows: Cristina Acidini Luchinat and Mario Scalini, eds., I tesori di un antiquario: Galleria di Palazzo Mozzi-Bardini, Ministero per I Beni e le Attività Culturali, Soprintendenza per I Beni Artistici e Storici per le Province di Firenze, Pistoia e Prato (Livorno: Sillabe, 1998); Alberto Bruschi, Stefano Bardini: Si scopron le tombe, si levano I morti (Florence: SP 44 Editore, 1992); Gabriella Capecchi, ed., Arte greca, etrusca, romana: L’Archivio storico fotografico di Stefano Bardini (Florence: A. Bruschi, 1993); Lynn Catterson, ed., Dealing Art on Both Sides of the Atlantic, 1860 to 1940 (Netherlands: Brill, 2017); Lynn Catterson, “Stefano Bardini & the Taxonomic Branding of Marketplace Style: From the Gallery of a Dealer to the Institutional Canon,” in Images of the Art Museum: Connecting Gaze and Discourse in the History of Museology, ed. Melania Savino and Eva-Maria Troelenberg (selected papers from the conference, Images of the Art Museum: Florence, September 26–28, 2013, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz-Max-Planck-Institut) (Berlin: de Gruyter GmbH, 2017), 41–64; Cristina De Benedictis and Fiorenza Scalia, Il Museo Bardini a Firenze: Le pitture (Milan: Electa, 1984); Lucia Ciotti Faedo, Enrica Neri Lusanna, and Bruno Santi, Il Museo Bardini a Firenze: Le sculture (Milan: Electa, 1986); Everett Fahy, ed., Dipinti, disegni, miniature e stampe, in L’archivio storico fotografico di Stefano Bardini (Florence: Alberto Bruschi editore, 2000); Fiorenza Scalia, “Il carteggio inedito di Stefano Bardini,” in San Niccolò Oltrarno, la chiesa, una famiglia di antiquari, ed. Giovanna Damiani and Anna Laghi (Florence: Comune di Firenze,1982), 199–208; and Roberto Viale, “Alcune considerazioni su Stefano Bardini ed i suoi allestimenti,” Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, classe di lettere e filosofia, 4th ser., 6, no. 2 (2001): 301–20.

[4] Bardini acquired the villa in 1891; it was sold in 1921, the year before his death. The numerous documents related to the ownership of the villa are contained in the ASEB. That Harnisch accompanied Salomon is established on the basis of the handwriting of the document, Attività Commerciale, 1901, Small envelope bearing the name “W. Saloman” and the dates, 1, 2, 3 May, ASEB, also discussed and cited in note 9.

[5] The Villa Marignolle was likely too remote, and by 1902 Bardini had acquired the Torre del Gallo for the purpose of displaying art. See small printed postcard; recto: photograph of Torre del Gallo; verso: printed text, excerpted: “Cartolina Postale Italiana (Carte Postale d’Italie) Vossische Zeitung. Berlino 25 Ottobre 1906. . . Il Palazzo Bardini in Piazza Mozzi di faccia al Palazzo Torrigiani era già rinomato come un ‘piccolo Bargello;’ la sua villa a Marignolle era conosciuta per il suo autentico addobbo e per i suoi numerosi bei mobili antichi, ambedue sorpassa molto la nuova villa. . . . . . Bode.” 1906, ASEB.

[6] The firm’s principles were Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909), William Rutherford Mead (1846–1928), and Stanford White (1853–1906).

[7] They sat together on a committee meeting convened in 1896 by Morgan to address the issue of the exportation of gold, for which see “To Stop Gold Exports,” New-York Tribune, July 23, 1896, 1, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress, accessed August 28, 2017, http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1896-07-23/ed-1/seq-1/.

[8] Evening Post Publishing Company, The Evening Post Record of Real Estate Sales in Greater New York, January 1900, 7: “William Salomon purchased the Arnold residence at the north corner of Fifth Avenue and Eighty-third Street, and sold to J. Pierpont Morgan the plot, 75x98.9, on the north side of Thirty-sixth Street, 175 feet east of Madison Avenue.” See also, “In the Real Estate Field,” New York Times, January 11, 1900.

[9] Small envelope bearing the name “W. Saloman” and the dates, 1, 2, 3 May, Attività Commerciale, 1901, ASEB.

[10] Report, Registered Paper RP/1902/85986, Morgan’s Nominal File, Victoria & Albert Archive, London. I am enormously grateful to James Sutton, Victoria & Albert Archive, for his long range assistance in locating the material regarding this event.

[11] “Joseph Henry Fitzhenry loaned and gave many objects to the Victoria and Albert Museum between 1870 and 1913. In 1910, to mark the opening of the new buildings designed by Aston Webb, he presented his collections of French porcelain and Dutch faience. Several other departments were also beneficiaries of his generosity. Born in 1836, Joseph Henry Fitzhenry was a prodigious art collector and dealer. He was a friend of the art collectors Sir Richard Wallace, George Salting and J. Pierpont Morgan, to the latter of whom he provided advice on purchases. According to his obituarist, ‘Nothing is certainly known about Mr. Fitzhenry’s origin or early life’. Fitzhenry was a founding member of the V&A’s Advisory Council, attending only one meeting before he died in London on 15 March 1913, aged 77. (1836–1913) He was buried in Brompton cemetery,” as quoted from “Joseph Henry Fitzhenry,” Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed August 28, 2017, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/j/joseph-henry-fitzhenry-1836-1913/.

[12] Report Registered Paper RP/1902/85986, Morgan’s Nominal File, Victoria & Albert Archive, London.

[13] The firm was founded in London in 1842. For Durlacher, see Mark Westgarth, “A Biographical Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Antique and Curiosity Dealers,” Regional Furniture 23 (2009): 90–91. For more on Durlacher, see also “Durlacher Brothers,” Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed August 28, 2017, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/d/durlacher-brothers/.

[14] Line item accounting for receipt of shipment, Duveen file 1/2, 1902, Morgan Library Archive, New York. Founded in London, Henry Duveen opened the New York office in 1879. For Duveen, and additional bibliography, see Westgarth, “Biographical Dictionary,” 91–92.

[15] Established in 1827 as a metalwork firm, by 1872 the company was located at 18 East 17th Street, New York, NY, advertising itself in the 1880s as “Designers and Manufacturers of artistic grates, open fire-places, fenders and chimney-piece novelties in every style.” Presently, the business, now branded as fireplace specialists, still occupies the same address. For their history, see “Wm. H. Jackson & Co., 138–144 Broadway, Brooklyn, N. Y., 2009,” accessed August 28, 2017, http://www.waltergrutchfield.net/jacksonwmh.htm and William H Jackson Company, accessed August 28, 2017, http://www.wmhjacksoncompany.com/.

[16] Wm. H. Jackson Company to McKim, Mead & White, October 19, 1904, box 268/file 626, McKim, Mead & White papers, New-York Historical Society, New York. The door frames are underway in the Spring of 1905, as recorded in a memorandum of McKim, Mead and White, dated May 25, 1905, box 269/file 627, McKim, Mead & White papers, New-York Historical Society, New York. I wish to thank to Christine Nelson for sharing with me these documents and those at notes 19 and 20.

[17] “Memoranda of sculpture, carving, etc., library of J. Pierpont Morgan, Esq. . . .” [undated, ca. 1905], box 268 or 269, McKim, Mead and White papers, New-York Historical Society, New York.

[18] Copy of letter from William Mitchell Kendall of McKim, Mead & White to Albert Hale, Pan American Union, Washington, DC, January 6, 1914: “In the center, a classic portal gives entrance to the building. The doors themselves are antiques, of bronze, Italian in design.” Operation Record Book 6, McKim, Mead and White, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York.

[19] The description is given in “Landmarks Preservation Commission, May 17, 1966, Number 9, LP-0239”: “The Pierpont Morgan Library and Annex, 29–33 East 36th Street . . . Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 866, Lot 25,” Neighborhood Preservation Center, accessed April 30, 2015, http://www.neighborhoodpreservationcenter.org/db/bb_files/PIERPONT-MORGAN-LIBRARY.pdf.

[20] Jan M. Seidler, “A Critical Reappraisal of the Career of William Wetmore Story (1819–95): American Sculptor and Man of Letters” (PhD diss., Boston University, 1985), 295. Waldo was actually born in Paris.

[21] For William Wetmore and additional bibliography, ibid.

[22] Kathleen Lawrence, “Where’s Waldo?: The Disturbing Disappearance of the Gilded Age Anglo-American Sculptor Waldo Story,” Sculpture Journal 18, no. 1 (June 2009): 67–85, esp. 80, evidently using the year the building was completed as the terminus post quem for the doors. Lawrence does not explicitly state, nor otherwise explain, the source of the attribution to Waldo.

[23] For Waldo Story, in addition to K. Lawrence, see Claire Jones. “A Creative Engagement with Historic and Modern Sculpture: Waldo Story’s ‘Fallen Angel,’” Sculpture Journal 23, no. 2 (2014): 145–58; and Evelyn March Phillipps, “Waldo Story: Sculptor,” Magazine of Art, n.s., 1, (January 1903): 137–40, 273–75.

[24] Seidler, Critical Reappraisal, 310.

[25] Jones, “Creative Engagement,” 146, and 146n8: “Whistler’s letter to Waldo Story, c. 3–10 April 1887, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Centre, University of Texas at Austin, TX; William Henry Hurlbert: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center, Story Archive. 26 letters to Story, William Wetmore, 1892–1894. Container 1.4, Ms Msc II. B.”

[26] Jones, “Creative Engagement,” 145–58.

[27] Phillipps, “Waldo Story,” 140.

[28] Ibid.

[29] “The New Tariff Law To Go Into Operation On July 1. How It Differs From the Old Law,” New York Tribune, June 30, 1883, 3. The tax was raised from 10 percent to 30 percent. On the history of the tariff and its revision, see Revision of the Tariff. Hearings Before the Committee of Ways and Means, Report (1890), 51st Congress, 1st Session, House of Representatives, Misc. Doc. No. 176, 616ff, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., Washington, DC.

[30] For which see “Residences,” The Morgan Library and Museum, accessed August 28, 2017, http://www.themorgan.org/about/pierpont-morgan-collector/4.

[31] For a history of the tariff, its revisions, and repeals, see Kimberly Orcutt. “Buy American? The Debate over the Art Tariff,” American Art 16, no. 3 (Autumn 2002): 82–91; and “The American Artists in Rome on the Art Tariff Question,” American Register, February 28, 1885, 5. On December 1, 1883, Waldo and his brother Julian, along with Albert Harnisch and some thirty others signed William Wetmore Story’s petition to the US Congress to repeal the duty on foreign art. “Petition of Artists in Rome, praying for the repeal of the duty on works of art,” Report (1884), 48th Congress, 1st Session, Senate, Congressional Series of United States Public Documents, Vol. 2171, Mis. Doc. No. 28, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., Washington, DC.

Again, in 1885, Harnisch was one of the thirty signatories on another of Story’s petitions to the US Congress to remove the tariff on imported foreign art, for which see M. Elizabeth Phillips, Reminiscences of William Wetmore Story, the American sculptor and author: Being incidents and anecdotes chronologically arranged, together with an account of his associations with famous people and his principal works in literature and sculpture (Chicago and New York: Rand McNally and Co., 1897), 233ff.

[32] “An interesting personage at Newport just now is Mr. Waldo Story, the son of the sculptor and poet, who lives in Rome. He is being entertained a great deal, and this is his first long visit in this country for years. His wife, who was a Miss Broadwood, a niece of Mrs. John A. Morris, does not accompany him. He represents, with Gheredesca, who is half American and with Sternberg, the foreign element at Newport this summer. There have never been so few counts and marquises and other titled gentlemen. Allloti has returned from a summer in London, and is much favored by the Astor set.” “Society,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 18, 1901, 13. In 1906, Waldo traveled to San Francisco, stopping over in Salt Lake City, for which see Salt Lake City Deseret Evening News, January 18, 1906, final edition.

[33] “The Fine Arts,” St. Albans Daily Messenger (VT), February 15, 1902, 4.

[34] “Music and Art,” Dallas Morning News, April 27, 1902, 13.

[35] Selected first was the model of Henry Shrady of Brooklyn, at the same time stating the “model of Charles H. Niehaus was so interesting that the final choice would lie between these two. Each was requested to submit a new model, about four feet in height, for the equestrian group.” It was further noted, “Mr. Shray, who is one of the younger sculptors, came into prominence last summer as winner of the Home monument competition in Brooklyn for a statue of Washington to cost $50,000. Before that he had done nothing of any size except a figure of a buffalo for the Pan-American Exposition. Mr. Shrady is a son of Dr. Shrady, who was Gen. Grant’s personal physician.” Ibid.

[36] “Davis Arch Design. Competition of Artists Rapidly Drawing to a Close,” Columbia Sunday State (SC), June 1, 1902, 7.

[37] “The Davis Memorial. Daughters of the Confederacy Decide to Erect an Arch. The Design of,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 6, 1902, 11.

[38] “Portrait Busts Done in Rilievo, Novel Phase of Portraiture Finds Favor in the East,” Minneapolis Journal, February 27, 1906, 8.

[39] “T. Waldo Story Dead,” New-York Tribune, October 24, 1915, 11, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress, accessed June 3, 2017, http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1915-10-24/ed-1/seq-11/; and “Waldo Story, Noted Sculptor is Dead,” New York Sun, October 24, 1915, 11. Oddly, there is no mention of the doors in the other New York obituaries, for which see, “T. Waldo Story, Sculptor, Is Dead,” New York Times, October 24, 1915, 17; “Waldo Story, Sculptor, Dies at Home Here,” New York Evening World, October 23, 1915, 3, final edition. Nor is it mentioned in the following obituaries: “Noted Sculptor Dead,” Marshalltown Evening Times-Republican (IA), October 23, 1915, 12; “Sculptor Story Dies,” Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, October 23, 1915, 3, final edition; and James C. Hyde and others, Art News (New York: Art Foundation Press, 1915), 14:4.

[40] I wish to thank Christine Nelson for putting me in touch with the family in 2015.

[41] Communicated via email August 10, 2015 by a family member who prefers to remain anonymous.

[42] McKim learns that Morgan has given him the project of the library on April 2, 1902, for which see the letter from Charles Follen McKim to William Rutherford Mead, April 2, 1902, reel 5, p. 483, Charles Follen McKim papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, with thanks to Christine Nelson.

[43] This is evident by the lack of material in the Morgan Archives in NY. I am assuming that Morgan’s records in London were of the same quality and quantity as what does exist today in NY.

[44] Invoice from Duveen Brothers, 302 Fifth Ave, NY, dated September 29, 1903, with line item dated November 1902: “To duty and freight on 2 Bronze Doors. . . .382,” D Duveen 1903 09 16, Morgan Collections Correspondence 1887–1948 (ARC 1310), Morgan Library & Museum Archives, New York.

[45] Stanford White had evidently visited Bardini’s galleries ca. 1884; that is, shortly after they opened. Writing to Bardini in 1889, Stanford White remarked that he had not seen Bardini’s collection for five years, for which see, White to Bardini, September 30, 1889, Corr. 1889, ASEB.

[46] In 1861, he became a partner in L.P. Morgan & Co. He married P. J. Morgan’s sister Mary Lyman on January, 1867; by 29, 1878 he continued the partnership in London, for which see Daniel A. Gleason, Memorial of the Harvard College Class of 1856: Prepared for the Fiftieth Anniversary of Graduation, June 27, 1906 (Boston: G.H. Ellis Co., 1906), 50.

[47] “Portrait Busts Done in Rilievo,” 8. It was reported that these commissions came from Mrs. Howard Burns, so possibly after the death of her husband in 1897.

[48] Charles Moore, The Life and Times of Charles Follen McKim (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1929), 173; and Letter from Charles Follen McKim to Samuel Abbott, August 1901: “I sincerely hope that [Waldo] Story will be able and willing to interest Pierpont Morgan in the subscription.”

[49] “I send you herewith the American Academy list headed by Mr. Morgan, whose signature was obtained through Mr. Story’s efforts of 48 hours ago.” Charles Follen McKim to Henry Walters, November 23, 1901, quoted in Moore, Life and Times, 173.

[50] Moore, Life and Times, 168; Waldo was appointed in 1898.

[51] Again, with thanks to Christine Nelson: Charles Follen McKim to Waldo Story, April 14, 1904, reel 5, Charles Follen McKim papers, Library of Congress. This information is again given in a description of the library in 1927, for which see, William Mitchell Kendall at McKim, Mead and White to Meta Harssen, June 1, 1927, file 472, McKim, Mead and White Papers, New-York Historical Society: “The ceiling of the west room of the Library was obtained from Stefano Bardini of Florence, Italy, and the color decoration was carried out by the late James Wall Finn. The fireplaces in the west, east and north rooms were obtained also from Bardini. All the above works were inspected by Mr. McKim and myself in July 1904. Mr. Bardini, who has since died, at that time occupied the Villa called Del Gallo near the Church of San Miniato. His son, I understand, still occupies the Villa. In Rome, furthermore, with the help of Mr. Waldo Story, we obtained the Porphyry Disc in the main entrance hall of the Library, and selected the various marbles for the rest of the pavement. This selection was based upon the floor in the celebrated Villa Pia in the Vatican Gardens.”

[52] From the 1890s, there are mentions too numerous to list, of what seems to be recurring bouts of illness, with fever, and long periods of convalescence. See, for example, letter dated July 14, 1905 from Robinson & Fisher in London to Bardini’s secretary in Florence mentioning that a planned sale of Bardini objects had to be canceled as a consequence of Bardini’s bad health. Correspondence Misc., 1905, AFEB.

[53] Though the individuals who had managerial roles changed over the years, at the time of the transaction of the doors, the top managers included Domenico Magno (1885–1908), Albert Harnisch, and Riccardo Nobili. Born in Constantinople, Domenico Magno worked in Paris, where he met Bardini in the 1880s. By 1885, Bardini hired Magno who moved to Florence and maintained a shop on Via dei Fossi, 25. See “Conti Saldati ricevute 1901” and “Affare Matelica 1889,” ASEB.

[54] Typescript: “Reminiscences of the late Pierpont Morgan Sr. as an art collector,” Box 1, Grace Nobili Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton.

[55] The painter and sculptor, Riccardo Nobili, was born in Florence, December 26, 1859. MS Grace Biography, Grace Nobili Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, MA; he died in Venice June 11, 1939 (as reported in the obituary by Selwyn Brinton in Apollo 30 (1939): 90. See also, “Signor Riccardo Nobili,” London Times, June 26, 1939, 9. Cf., Nobili also wrote A Modern Antique, A Florentine Story (Edinburgh: W. Blackwood and Sons, 1908), and The Gentle Art of Faking A History of the Methods of Producing Imitations & Spurious Works of Art from the Earliest Times Up to the Present Day (London: Seeley, Service & Co., 1922).

[56] Referring to William Salomon.