The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|

La matière de l’étrange, Jean Carriès (1855-1894) Catalogue : |

|||||

|

Last fall, while the Exposition Gustave Courbet sustained long lines at the Grand Palais across the street, the Petit Palais mounted an equally impressive display of the sculptures and ceramics of the French artist, Jean-Joseph-Marie Carriès. Visitors to the Petit Palais have long been exposed to Carriès work, where a selection of his sculptures and ceramics has been periodically on view in the permanent collection for more than a century. La matière de l’étrange, Jean Carriès (1855-1894) contained artworks from the museum’s vast collection of Carriès’ works, and was the first modern, large-scale exhibition devoted to this artist since 1930 (fig. 1). |

|||||

|

In 1904, the Petit Palais acquired 269 works of art in wax, terra cotta, painted plaster and bronze from the executor of Carriès’ estate, Georges Hoentschel (1885-1915), his friend and fellow ceramicist; a year later, the Petit Palais opened its first room devoted to the artist. A writer in the Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs noted at the time that “there are works in cire vierge, bronzes à cire perdue, pottery of enameled stoneware laid with gold and silver, busts in patinated plaster, stoneware, etc.; in fact Carriès work is represented in all its diversity. Among the sculpture should be noted the artist’s portrait of himself, the bust of a bishop, the Velasquez, the Martyrdom of St. Fidelis, and several other busts—Gambetta, Baudin, Jules Breton, Vacquerie, etc.”1 An attempt to recreate the original Salon Carriès seems to have been one of the major objectives of the present exhibition, as many of the works mentioned in this review were included. |

||||||

|

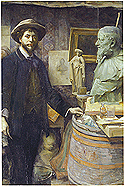

La matière de l’étrange was organized into six chronological sections. The first, a gallery that acted as a prologue to the exhibition called “Dans l’atelier de Carriès,” began with Louise Breslau’s (1856-1927) portrait of the artist surrounded by his works in his Paris studio (fig. 2). This exhibition space also contained reproductions of some of Carriès’ work in various materials, and visitors were encouraged to touch these reproductions, not only to gain a sense of the texture of the materials Carriès used, but also to illustrate what happens to sculpture when it is touched too much—an essential lesson for the museum-visiting public. The process of casting was also illustrated in this small space to illustrate the way that sculpture and its editions were produced in the nineteenth century. |

|||||

|

The second gallery was entitled “L’Orphelin Lyonnais.” Displayed here were some of Carriès’ earliest works, revealing the development of styles and themes that would remain constant throughout the rest of his career. As suggested by the title of this segment of the exhibition, Carriès, his two brothers and one sister were raised in an orphanage in Lyon, France, after the death of their parents from tuberculosis. They were placed in the charge of the Mother Superior, Sister Marie-Anne Agnès Callamand, called Mère Callamand (1810-1882), who recognized Carriès as a talented child and placed him in an apprenticeship in the town church, the Cathedral Saint-Jean, with the sculptor of devotional objects, Pierre Vermare (1835-1906). Carriès later attended the École des beaux-arts in Paris where he studied under Augustin-Alexandre Dumont (1801-1884). |

||||||

|

Carriès’ admiration and devotion to Mère Callamand are evident in one of the first, and most impressive, sculptures in the exhibition—the work entitled La Religieuse (Mère Callamand) from around 1888 (fig. 3). The figure’s expression, which is difficult to categorize, seems to contain a stern look with a mouth about to break into a smile of approval; a demonstration of Carriès’ skill and the nuances of his modeling techniques. Also evident in this plaster are the characteristics of Carriès’ signature works: his interest in medieval and religious subject matter, elaborate costuming, and subtle yet dramatic facial expressions. His use of variously colored patinas added a range of hues to his sculptures, corresponding with the new interest for chromatic sculpture during the second half of the century. These characteristics, along with Carriès interest in drama, spiritualism, timelessness and interior states of being, place him at the forefront of the Symbolist movement in France. |

|||||

|

“Portraits et figures de fantaisie,” the third and largest gallery in the exhibition, contained the bulk of Carriès’ most significant works. Here visitors were exposed to the contemporary and historical portraits and têtes d’expression for which Carriès is best known. One entered the gallery facing the large wax and plaster in the round entitled Le Martyre de saint Fidèle (1893), a dramatic sculpture representing the rarely-depicted martyrdom of Saint Fidelis of Sigmaringen, killed for his preaching in Grisons, Switzerland on 24 April 1622 by the Protestant Zwinglians; the work is a testament to both Carriès’ interest in religious subject matter and his flare for the dramatic. A large glass case on the left wall of the gallery contained seven sculptures known as “Les Désolés,” or the Desolate Men. (fig. 4). The case included one of Carriès most recognizable works, L’Aveugle (The Blind Man, 1879). Théophile Gautier noted that “these heads, on the ends of shoulders as if mutilated, posed straight with neither pedestal nor a socle base, are so striking that one would believe them to be at first glance to be modeled from life.”2 The excellent lighting and grey green walls of the exhibition’s design assisted in emphasizing the various colors of Carriès’ materials. In addition to these heads, one found Carriès’ impressive life-sized self-portrait in wax and plaster, a work cast in bronze in 1914 to be placed on his tomb at Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris (fig. 5 and fig. 6). The sculpture contains references to the important influences in Carriès’ life: The artist holds a maquette of a sculpture of the baroque printmaker Jacques Callot and he is supported, literally and figuratively, by a mask of his deceased mother at his lower right. Interestingly, Callot (c. 1592 – 1635) was an artist who made caricatures and commedia dell arte figures, in addition to a famous print of the martyrdom of Saint Fidelis; thus one sees the obvious connection between Callot and Carriès and the homage that the sculptor paid to the printmaker in this work. |

||||||

|

Carriès’ images of children were also displayed here. In addition to a small grouping of babies’ heads in various states of wakefulness and sleepiness, his L’Infante (also called La Fillette au pantin) was also on view. In this delightful work, a female child, who looks like a Dutch or Spanish princess, seemingly teeters on one leg while wearing a fat-cheeked pout and wide-eyed expression. She clutches tightly a small puppet, who wears a distressed expression and whose legs seem to cling to the child for his life. These works were made in editions, and a recently acquired version of L’Infante can also be seen in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (fig. 7). One wonders how a man who never had a family of his own could so succinctly capture the fleeting expressions of infancy. |

||||||

|

Carriès body of work in the medium of ceramics was treated in the fourth gallery, entitled “Le Grès, entre tradition et modernité.” Carriès saw an exhibit of Japanese stoneware at the 1878 Exposition Universelle that altered the course of his career. Some of the works on exhibit at the Exposition Universelle included Japanese masks in the “grotesque” style. Carriès’ “grotesques” were wonderfully presented, hung in a fashion that made them appear to float in space against the wall, and were reminiscent of masks used in traditional Japanese Noh theater (fig. 8). In an adjoining room, one could find the charming mystical animals of Carriès’ imagination. His Grenouille à oreilles de lapin (Frog with rabbit ears, c. 1892) graces the cover of the exhibition (fig. 9). The frogs were the silent stars of the exhibition catalogue: a frog “footprint” could be found on various sites on the floor, drawing the attention of visiting children to these imaginative creatures. Furthermore, curator Amélie Simier chose the best examples of the artist’s ceramic vessels from the large collection at the Petit Palais. This visitor was taken aback by the gracefulness of the shapes and the skill with which the various glazes were applied (and dripped) on these objects. Carriès’ Pots cabossés (dented pots) are among the most modern objects in the museum’s collection. |

||||||

|

Possibly one of the most heart-wrenching losses in the history of art is discussed in the fifth gallery, labeled “La Porte monumentale.” The work known as La Porte de Parsifal was commissioned from Carriès in 1889 by Winnaretta Singer, Princess de Scey-Montbéliard (1865-1943, later the Princess de Polignac), art patron and heir to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune, for the room in her home where she kept the original manuscript for Richard Wagner’s 1882 opera Parsifal (fig. 10). Wagner’s opera was based on Wolfram von Eschenbach’s thirteenth-century epic poem on Parsifal’s search for the Holy Grail. Who better to compose an archway for the Singer’s medieval-style Parsifal Room than Carriès? The exhibition contained, however, only fragments from La Porte de Parisfal, along with drawings and photographs of the work in progress. |

||||||

|

It is said that every great artist dies without achieving their last great work, although many start the process without ever seeing the work come to fruition. La Porte de Parsifal contained many of Carriès whimsical “grotesques” and was to have as its miniature trumeau a standing sculpture of Winnaretta Singer herself. The artwork was plagued, however, by technical problems and the artist’s failing health. Carriès died at the age of thirty-nine, after suffering from a lung disorder known as pleurisy, an infection of the lungs similar to the tuberculosis that killed his parents. The most realized version of La Porte de Parsifal, a large-scale maquette for the work, was acquired by the Petit Palais in 1904. In 1935, this version of La Porte de Parsifal was ordered to be destroyed by one of the Petit Palais’ own curators (the late Raymond Escholier) to make room for a permanent exhibition of Italian art. As a consequence, we feel deeply the loss of this work because of a curator’s personal taste and the ever-changing judgments of the art world and its historians. La Porte de Parsifal has many similarities to Auguste Rodin’s La Porte d’Enfer: both occupied their creators for much of their late careers and both were never completely realized. But at least with Rodin’s work, one can still visit the Musée Rodin in Meudon and see the master sculptor’s final realization of his Porte. (Until, heaven help us, someone in the future decides that Rodin is passé and takes a hammer to it.) |

||||||

|

After passing a small alcove containing copies of the catalogue for review, the final gallery of the exhibition dealt with “La Postérité de Carriès.” It was a small space containing the history of the acquisition of Carriès’ works from Hoentschel. Although he was not mentioned in the exhibition, an American cannot help but see connections between Carriès and George E. Ohr (1857-1918), known in his day (and through his own promotion) as “the Mad Potter of Biloxi.” Ohr promoted the Arts and Crafts style and ceramics-as-fine-art aesthetic to Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The new Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art in Biloxi, Mississippi, with its Frank Gehry designed building, plans to open this year and will certainly create a new generation of fans for this type of art. In many ways Ohr continued where Carriès, an artist much too quickly silenced, left off. |

||||||

|

The exhibition was accompanied by a scholarly catalogue, a substantial exhibition visitors guide (called the Petit journal de l’exposition) and a small guide in the style of the “Découvertes Gallimard” series, with many nice color images and fold-out pages, intended for younger devotees of Carriès or new initiates to his work. This variety of publications satisfied every type of viewer, from the art historian to the casual adult visitor to the younger person who is lucky enough to be taken to this museum. The scholarly catalogue is substantial, with seven chapters comprised of essays by Mme Simier, Laurence Chicoineau, Patrice Bellanger, Édouard Papet, Dominique Morel and Jean-Michel Nectoux. Included is an index of important names, an updated bibliography for the artist, and an informative biography/chronology. An exhibition checklist, listed by the room in which each work was exhibited, is also provided so that one could get a full picture of which works appeared in which rooms. |

||||||

|

A word or two should be said about attendance: I have often heard from colleagues the complaint that exhibitions of sculpture are chronically under-attended, both here in the United States and abroad. Something of the sort had been mentioned to me with regard to this exhibition, by two separate colleagues unaffiliated with the museum who saw the show and loved it, but thought it was under-visited. Low attendance at sculpture exhibitions is not really the fault of the museum curators or the art-viewing public. Frankly, it seems to be the fault of our academic discipline, where there are still very few courses taught on the undergraduate or graduate level in the history of sculpture, and where architecture and painting are still very often treated as something special and sculpture as something complementary. (Case in point: there is no canonical textbook for the history of modern sculpture currently in print for use in classrooms.) Museums like the Petit Palais that venture outside of the norm and organize large-scale sculpture exhibitions with scholarly catalogues are doing what they can to bring a better understanding of the medium to the public in general and to the art world at large. |

||||||

|

The Petit Palais took a risk when they mounted an extraordinary exhibition devoted to Jean Carriès, an underappreciated but enormously creative genius. Like many sculpture exhibitions, it unfortunately did not travel, most likely due to the fragility of the works and the expense of transportation and insurance. Yet, for those who could see it in Paris, this exhibition presented a much-needed overview of the artist’s oeuvre, so important to the understanding of sculpture and of the Symbolist movement in France at the end of the nineteenth century. The Petit Palais raised the bar for sculpture exhibitions with its attention to innovative exhibition design, scholarly presentation and various publications, and its visitor-friendly interactive elements (inexpensive brochure, audio guide, froggy “footprints” for the kids, objects to touch to get that innate haptic response out of the visitor’s system, etc.). It was a risk that we must thank the curator and the museum’s director for taking. |

||||||

|

Caterina Y. Pierre, Ph.D. |

||||||

|

Related Links: Official Site for the Petit Palais: Arts and Crafts Home, Biographies of French Art Ceramicists: Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art, Biloxi, Mississippi |

||||||

|

I wish to express my thanks to Dr. Amélie Simier, Conservateur du Patrimoine and curator of the Jean Carriès exhibition, for her helpful assistance in Paris and for supplying and permitting the reproduction of the photographs in this review. My study trip to Europe was made possible through a PSC-CUNY Travel Grant. 1. Th[eodore] Beauchesne, “Notes from Paris,” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 6:23 (February 1905), 421. 2. Théophile Gautier, 1881, as quoted in Amélie Simier, “C’est le Moi dans le Rêve…” De quelques procédés plastiques au service de l’étrange,” in La matière de l’étrange, Jean Carriès (1855-1894), Paris : Paris-Musées, 2007, 99. [“Ces têtes, sur des bouts d’épaules comme déchiquetées, posées à plat sans piédouche ni socle, sont tellement saisissantes qu’on les croirait au premier abord moulées sur le vif.”] |

||||||