The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

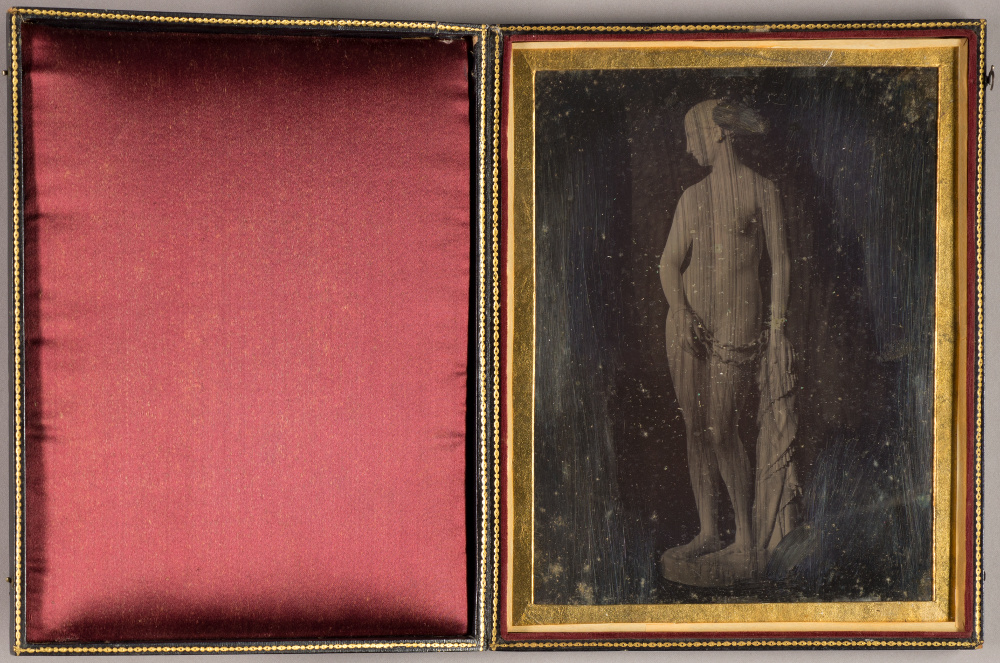

At first glance, the daguerreotype of Hiram Powers’s Greek Slave in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) seems unremarkable (fig. 1). The plate is permanently scarred by scratches and fingerprints that make the image difficult to read, and the picture is so faded that, in a certain light, portions of it all but vanish. For a brief time, the object was erroneously catalogued as a mirror and almost lost to history.[1] Yet this daguerreotype is enormously valuable because it offers something new to a composition that has become so familiar. When scrutinized closely, the image of the sculpture, shown in mirror reverse, reveals remarkable anomalies as compared to the statue as we know it; among the differences are the clasp connecting the chain to the figure’s proper right hand, the arrangement of the drapery, and the apparent omission of the Phrygian cap. These details make the case that this is not just another reproduction of the famed sculpture but the only known image of the lost version of The Greek Slave, completed in the fall of 1848 for William Humble Ward, the 1st Earl of Dudley, and missing since before World War II.

Fig. 1, Unknown maker, The Greek Slave, ca. 1848–49. Daguerreotype. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

Note: A daguerreotype presents a reverse image of its subject, thus The Greek Slave appears “flipped” across its vertical axis.

Lord Ward, as Powers referred to his patron, first admired The Greek Slave in the artist’s studio in December 1843.[2] He likely saw both the plaster pointing model and the first marble replica midway through carving, the latter of which was soon after purchased by Captain John Grant. Ward approached Powers the following September and commissioned his own marble replica, entreating the artist to modify the composition. As Powers recorded in his “Studio Memorandum”—a notebook now at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art—Ward “desire[d] the support to be changed a little in the drapery (more careless).” Powers further noted, “[I] must write to him . . . and enclose design of the alteration—he spoke of the mouth of the Slave—liked that of the model best—but finally said I must make the duplicate all the same except the drapery.”[3] Powers satisfied Ward’s demands by omitting one twist of the fabric around the supporting column in this 1846 version.

Following a circuitous turn of events that are well documented elsewhere, Ward ended up releasing his claim on this unique version of The Greek Slave so that the artist could send it to America for exhibition, and the sculpture—generally referred to as the second version—finally passed to another collector (and is now in the Corcoran Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC) (fig. 2).[4] Powers expressed his indebtedness to Lord Ward, writing, “Your kindness in allowing me to keep the statue originally intended for you, has laid me under many obligations to you.”[5] When, in 1848, the sculptor at last fulfilled Ward’s order for a personal replica, he once again complied with his patron’s insistence on a unique version of The Greek Slave. Shortly after completing this sculpture (the fourth version), Powers wrote to his client, “The new arrangement of drapery made at your request has been greatly admired, and I like it myself quite as well as the other.”[6] It is difficult, however, to know precisely how Ward’s sculpture differed from the other examples of The Greek Slave, in part because the daguerreotype shows only one view of the three-dimensional sculpture. In a letter to Prince Anatole Demidoff, who commissioned the fifth marble example soon after this exchange, Powers commented more sincerely on the new drapery and enumerated the differences between Ward’s sculpture and the original design:

The changes made at the request of Lord Ward have enlarged (necessarily) the support, thereby encumbering the view of the statue to some extent, and if there is any improvement in the effect of the drapery itself (which some have doubted) it is a question how far it may have been counterbalanced by the encumbrance it has added to the view of the statue. The workmanship upon the original is much the most elaborate, and extensive: in [sic] the Grecian cap at the top of the support and the embroidered sleeved at the outer side are left out in the one for Lord Ward.[7]

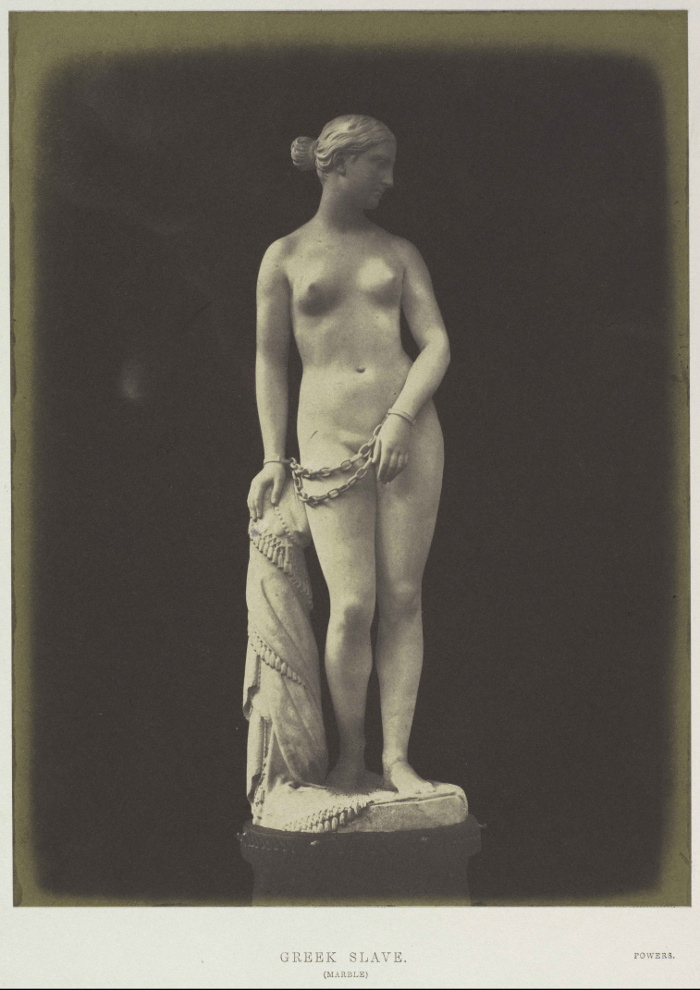

Fig. 2, Hiram Powers, The Greek Slave, 1846. Plaster. Corcoran Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

In this letter, Powers refers to enclosed “sketches from [both] the original and [the] altered support for ‘The Slave,’” none of which have been located. (For an account of Demidoff’s commissioning and display of the fifth version, see Helen A. Cooper’s article.)

The lost Greek Slave was widely seen by visitors to Lord Ward’s lavish estate, Witley Court, in Worcestershire, England, which boasted a large art collection that included sculptures by European masters Bertel Thorvaldsen, Antonio Canova, and Francis Legatt Chantrey.[8] Thousands more saw Ward’s Greek Slave when he loaned it to the Art Treasures of the United Kingdom exhibition that took place in Manchester in 1857.[9] Both Witley Court and the Manchester exhibition are richly documented in period photographs, but remarkably, neither of them includes a view of Lord Ward’s Greek Slave.[10] A late-nineteenth-century account mentions The Greek Slave on display in the Long Gallery at Witley Court and recaps the debate between patron and artist over proposed changes to the composition that concluded with “Lord Dudley [becoming] the possessor of the original statue, minus the [Phrygian] cap.”[11]

In the absence of sketches or comparative photographs, we can rely only on Powers’s letters and the fleeting description of Ward’s marble to determine if the sculpture shown in the Smithsonian’s timeworn daguerreotype is, in fact, the fourth replica of The Greek Slave. The most compelling point is the apparent absence of the Phrygian (Grecian) cap in the daguerreotyped sculpture. This element, so important to Powers’s narrative about freedom and bondage, is quite prominent in all other examples of The Greek Slave (fig. 3); its omission from the fourth replica is a major departure from the composition as we know it. Another area of difference is the arrangement of the folds of fabric that cascade down the vertical support, especially in the section along the outer edge of the column, at the height of the figure’s lower calf (fig. 3a). In this passage in the daguerreotyped sculpture, just below the tasseled hem of the lower twist of fabric, the cloth’s scalloped edge forms an unusual triangular shape that overhangs in such a way that it creates a pocket of deeply shadowed space.

Note: Use the tools available on your device to move and zoom.

Fig. 3, Photograph of the daguerreotype after conservation treatment and without its glass plate. Courtesy of Mirasol Estrada, Lunder Conservation Center, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

Fig. 3a, Detail of the lower section of the draped column.

Fig. 3b, Detail of the manacle with the elaborate clasp to the chain.

Fig. 3c, Detail of the thumb encircled by the chain link.

The most distinctive idiosyncrasy in the daguerreotype’s sculpture is the double clasp that joins the chains to the manacle on the figure’s proper right wrist (reversed in the daguerreotype) (fig. 3b). No other example of the sculpture has such a large, finely rendered clasp. Oddly, Powers’s letter to Prince Demidoff does not call out this stunning feature, perhaps because it proved too elaborate to execute more than once and the artist did not wish to encourage other clients to request it for subsequent commissions. It is important to note that the fragile chains on most examples of the sculpture have been repaired multiple times over the years. An early photograph (1851, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) of the first replica of The Greek Slave (1844, Raby Castle, Staindrop), taken just a few years after the completion of the sculpture, when the original chains were presumably fully intact, illustrates how much the chains in the daguerreotype differ from those on other examples of the sculpture (fig. 4). Although early photographs of The Greek Slave often were made of Parian ware reductions of Powers’s original, in part because they were easier to light and manipulate due to their size, the sculpture in this daguerreotype is unmistakably marble, a quality evinced by the level of detail and finish of the chains and tassels.[12] One slender chain link is so fine that it slips over and nearly encircles the figure’s proper left thumb, a testament to the bravura carving of the marble (fig. 3c).

Fig. 4, Hugh Owen, Greek Slave, 1851. Salted paper print from paper negative. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, www.metmuseum.org.

It seems highly likely that this daguerreotype was made in Powers’s studio. The sculptor completed the fourth marble replica in October 1848, but it took Ward months to issue the final payment.[13] The sculpture languished in Powers’s studio until October 1849, giving him ample time to have it daguerreotyped. Unlike some artists who were wary of photography, Powers embraced this new technology, allowing select studio visitors to take their own daguerreotype “impressions from the Slave.”[14] Powers also used daguerreotyping as a tool for marketing his work to potential clients in the United States, and he sent images of The Greek Slave in particular to contacts in Philadelphia and England.[15]

The provenance of this daguerreotype leads directly to Miner K. Kellogg (1814–89), which offers further evidence linking the object to Powers’s studio. In the 1840s, Kellogg served as Powers’s agent in the United States, and he was responsible for managing segments of the nationwide tour of The Greek Slave, which Tanya Pohrt and Cybèle T. Gontar examine in their articles. Although the two artists eventually had a volatile falling out, they were still in contact in 1849, when Powers wrote to Kellogg that he had finally secured payment from Lord Ward for the fourth replica of The Greek Slave.[16] Powers may have sent the daguerreotype to Kellogg around this time, or given it to him during the latter’s subsequent visit to Florence. Kellogg died in Toledo, Ohio, in 1889, leaving the daguerreotype to his only child, Virginia Somers Snyder. Following Snyder’s death in 1937, much of her estate was purchased by Martha F. Butler of Alexandria, Virginia, who bequeathed the daguerreotype to SAAM in 1991, along with more than four hundred works by Kellogg.[17]

In 2014, photography conservator Mirasol Estrada examined and treated the daguerreotype at the Lunder Conservation Center at SAAM, in preparation for its inclusion in the exhibition Measured Perfection: Hiram Powers’ Greek Slave (July 3, 2015–February 19, 2017).[18] Estrada observed that the plate was not highly polished before exposure, and as a consequence, contrast in the image is relatively poor, suggesting it was made by an amateur daguerreotypist, even though the plate is full size, which would have been expensive. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) was used to test for traces of gold, an element that was commonly used to fix early daguerreotypes and would support the dating of this object to around 1848 or 1849. However, the seal on the plate package was found to have been broken, raising the possibility that the copper plate had been cleaned at some point, perhaps with thiourea, which would have washed away traces of gold. Since thiourea contains sulfur, XRF testing was also used to search for traces of that element. No sulfur was found, but it is possible that the sulfur was washed away during subsequent attempts to clean the plate. Furthermore, tarnish on the corners of the plate suggests that it once had a different window mat. In short, the daguerreotype offers little conclusive evidence about where and when it was made, but its physical properties do not rule out the possibility that it was made while the sculpture was still in Powers’s studio in Florence.

The disappearance and possible destruction of Lord Ward’s Greek Slave only adds to the mystery of the sculpture in this daguerreotype. The catalogue raisonné of Powers’s work states that this sculpture was “destroyed in the burning of Whitley [sic] Court by enemy action, 1944.”[19] It seems more probable, however, that the sculpture was destroyed or perhaps moved from Witley Court well before this date. In 1920, William Humble Ward’s son, the 2nd Earl of Dudley, sold Witley Court and many of its contents to Sir Herbert Smith.[20] It is unknown if the 2nd Earl of Dudley sold The Greek Slave or moved the sculpture to Himley Hall, where he resided until his death in 1932.[21] If The Greek Slave remained at Witley Court, it may have been destroyed in a fire that consumed much of the estate in September 1937, after which Sir Herbert was forced to auction what little survived the conflagration.[22]

Unless the fourth replica ever comes to light again, all that remains of Lord Ward’s unusual Greek Slave is this elusive image in a singular daguerreotype.

Digital Humanities Project Narrative

There is no substitute for looking at an artwork in person, especially sculpture in the round, which is intended to be viewed from multiple vantage points. But developments in digital technologies are rapidly augmenting our ability to see and interpret physical data.

My focused study of the full-scale pointing models of Hiram Powers’s Greek Slave began after a day of “close looking” at objects in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s (SAAM) deep storage with Martina Droth, deputy director of research and curator of sculpture at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven. We spent hours together examining molds, plasters, and body casts from Powers’s studio, speculating about the sculptor’s methods and the relationship among certain objects. Why were there two full-scale pointing models of the The Greek Slave? When were they made? How closely does the body cast of a hand and forearm match the corresponding section of The Greek Slave? I may not have asked these important questions had it not been for this brainstorming session with a fellow sculpture scholar in front of the objects.

Answers to these and other questions were best pursued in the laboratory using various digital technologies. Digital X-radiography conducted at SAAM’s Lunder Conservation Center revealed armatures and seam lines of the plasters being examined, while 3-D scans and modelling generated by the Smithsonian’s Digitization Program Office allowed us to quantify deviations in size and shape between select objects. These studies critically shaped the SAAM exhibition Measured Perfection: Hiram Powers’ Greek Slave. But exhibitions are ephemeral, and so it is most satisfying to see this “born-digital” documentation and research find a permanent platform in this online publication of Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide. This special issue places my essays, “From Skeleton to Skin: The Making of the Greek Slave(s)” and “Discovering the Lost Greek Slave in a Daguerreotype,” in the rich context of related papers and digitized archives, most notably the trove of Hiram Powers’s papers at the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art’s trove of Hiram Powers’s papers, allowing readers to oscillate to other articles and images. This fluidity is particularly useful when considering differences across the various marble replicas of The Greek Slave. Zoom features accompanying certain images in this publication allow readers to study Powers’s sculptures from all sides and to bring into close focus, for example, the artist’s inscription, abrasions left by the chains, graphite pointing marks, and other surface details that are not plainly visible or accessible in typical museum settings. Working in this way brings our highly collaborative research to a global readership and makes our methods of inquiry more transparent. We hope this collection of articles will encourage other institutions to 3-D scan the various full-scale marble examples of The Greek Slave and further the discourse that begins here.

The author is grateful to Ann Shumard and Mirasol Estrada for taking time to share their knowledge of daguerreotypes and photographic processes, to Jennifer Wagelie for her comments on an early draft of this paper, and to William H. Gerdts for playing a superb devil’s advocate during early stages of my research.

[1] A note in the registrar file at the Smithsonian American Art Museum dated August 6, 1993, states that the object was “misidentified . . . as a ‘black leather case with mirror interior.’”

[2] Hiram Powers, “Studio Memorandum, 1841–1845,” December 1, 1843, Hiram Powers Papers, box 10, folder 26, frame 32, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (henceforth AAA), http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/-Studio-Memorandum-Etc--284723.

[3] “Studio Memorandum,” September 23, 1844, frames 80–81.

[4] Richard P. Wunder, Hiram Powers: Vermont Sculptor, 1805–1873 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1991), 2:163.

[5] Powers to Lord Ward, July 28, 1848, Florence, and Lord Ward to Powers, [no date], Vichy, Hiram Powers Papers, AAA, box 9, folder 54, frames 4 and 18–20, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/ward-lord-284698.

[6] Powers to Lord Ward, October 12, 1848, Florence, Hiram Powers Papers, AAA, box 9, folder 54, frame 8, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/ward-lord-284698.

[7] Powers to Prince Anatole Demidoff, November 2, 1849, Florence, Hiram Powers Papers, AAA, box 3, folder 19, frames 7–8, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/demidoff-prince-284289. Powers actually offered Demidoff the fourth replica, just before Lord Ward agreed to remit final payment on the sculpture. See Powers to George Peabody, September 15, 1849, Hiram Powers Papers, AAA, box 7, folder 28, frame 50, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/Peabody-George-284563.

[8] For the history of Witley Court, see Richard Gray, Witley Court: Hereford and Worcester (London: English Heritage, 1997), 9–27; Bill Pardoe, Witley Court: Life and Luxury in a Great Country House (n.p.: Peter Huxtable Designs, 1986), 12–39; and John Martin Robinson, Felling the Ancient Oaks: How England Lost Its Great Country Estates (London: Aurum Press Limited, 2011), 193–201.

[9] In his two-volume biography and catalogue raisonné on Powers, Richard Wunder incorrectly states that replicas one and four were exhibited in Manchester. See Wunder, Hiram Powers, 2:159 and 166. However, the exhibition catalogue clearly identifies Lord Ward as the lender of The Greek Slave: “Catalogue Number 94,” in Catalogue of the Art Treasures of the United Kingdom Collected at Manchester in 1857 (Provisional), 2nd ed. (London: Bradbury and Evans, 1857), 141, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433084939366;view=1up;seq=141.

[10] For photographs of Witley Court, see [Henry] Bedford Lemere, “The Sculpture Gallery at Witley Court,” 1920, Historic England online archive, Swindon, England, http://archive.historicengland.org.uk/results/Results.aspx?t=Quick&cr=Bedford%20Lemere%20Witley%20Court&io=False&l=all&page=1.

[11] A. M. [Alice Mangold] Diehl, Musical Memories (London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1897), 183–4, https://books.google.com/books?id=FvEsAAAAYAAJ&dq=Musical%20Memories%20Alice%20Mangold&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[12] For example, see http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/286313.

[13] George Peabody, an American banker who lived in London, intervened on Powers’s behalf and secured Lord Ward’s final payment for the sculpture, which shipped from Florence via Livorno to London in October 1849. See Powers to Peabody, November 2, 1849, Florence, Hiram Powers Papers, AAA, box 7, folder 28, frames 60–63, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/Peabody-George-284563.

[14] “Countess Bielinska and her daughter—Polanders—sat for a daguerreotype likeness at their request—also allowed them to take impressions from the Slave,” in “Studio Memorandum,” May 7, 1844, frame 66.

[15] Powers promised to send “daguerreotypes of Slave” to a Mr. Hare of Philadelphia, June 13, 1844. See “Studio Memorandum,” frame 69. Similarly, he wrote to Lady Stamer: “Told her of my prosperity—might send Eve to England if the Slave succeeds there—would not forget the daguerreotypes for her.” See “Studio Memorandum,” October 1, 1844, frame 83.

[16] Powers to Miner K. Kellogg, October 26, 1849, cited in Wunder, Hiram Powers, 2:166.

[17] The Butler bequest included the objects listed here: http://americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artwork/results/index.cfm?rows=10&q=Martha+F.+Butler&page=33&start=320&x=0&y=0.

[18] Mirasol Estrada, “Examination and Treatment Report for The Greek Slave—Daguerreotype,” November 14, 2014, Lunder Conservation Center, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

[19] Wunder, Hiram Powers, 2:166.

[20] Gray, Witley Court, 14.

[21] Gray, Witley Court, 14–15; and Robinson, Felling the Ancient Oaks, 195.

[22] A 1938 sale catalogue is mentioned in Gray, Witley Court, 27.