The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Her Paris: Women Artists in the Age of Impressionism

Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO

October 22, 2017–January 14, 2018

Speed Art Museum, Louisville, KY

February 17–May 13, 2018

Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA

June 9–September 3, 2018

Catalogue:

Women Artists in Paris, 1850–1900.

Laurence Madeline, with Bridget Alsdorf, Richard Kendall, Jane R. Becker, Vibeke Waallann Hansen, and Joëlle Bolloch.

New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the American Federation of Arts, 2017.

288 pp.; 150 color illus.; bibliography; index.

$40.00 (soft cover)

ISBN: 9781885444455

$65.00 (hard cover)

ISBN: 9780300223934

The exhibition Her Paris: Women Artists in the Age of Impressionism, at the Denver Art Museum (DAM), was organized by the American Federation of Arts, and guest-curated by Laurence Madeline, formerly chief curator of fine arts at the Musées d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva. It will travel to three venues in the U.S. from October 22, 2017 through September 3, 2018. Originally titled Women Artists in Paris, 1850–1900, it has been renamed for its Denver venue, and curated locally by Angelica Daneo, curator of painting and sculpture at the DAM. The curators have assembled nearly ninety paintings, generally of high quality, by thirty-seven women artists from eleven countries, including well known artists of the Parisian avant-garde, such as Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, and many lesser known figures, most of whom practiced more conventional styles. The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue with six essays that provide important insights and a wealth of information regarding contexts, issues, artists, and individual artworks. Both catalogue and exhibition aim for accessibility, and seem directed at a general as well as a scholarly audience.

As the press releases claim, the show is truly groundbreaking. The large number of women artists it brings together for the first time, many virtually unknown and deserving of further study, their proficiency at diverse styles, the surprisingly wide range of subject matter and national origins, will come as a revelation to the public and even to many scholars of nineteenth-century art. The exhibition deepens our knowledge of the history of nineteenth-century art, and along with the catalogue, it makes an important contribution and opens the door for future scholarship.

Historically, as Linda Nochlin famously brought to our attention in 1971, women’s ambitions to become professional artists were thwarted by social norms and cultural expectations concerning female behavior, as well as by the lack of opportunities for training, especially the impossibility of studying the male nude, a prerequisite for the figurative history painting that comprised the most prestigious category of traditional art.[1] All over Europe, until late in the nineteenth century, women were barred from the government-run academies where male students trained to create such works. Thus, most women artists tended to specialize in the lesser categories like still life and portraiture. The small number who escaped these constraints and ventured into multi-figured history and genre painting often were the daughters or wives of male artists. However, this exhibition takes as its premise that despite the restrictive Victorian culture that pressed women into the private domestic sphere, and despite the fact that women were not admitted to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts until 1897, Paris, the center of the art world in the second half of the nineteenth century, offered unparalleled opportunities for training, exhibition, and exposure to modern and traditional art to aspiring women artists. They could study in private ateliers, like the Académie Julian, and exhibit their work at the Salon and at other group exhibitions and galleries, and a few even were welcomed into progressive circles, such as that of the Impressionists. Yet others formed their own organization, the Union des Femmes Peintres et Sculpteurs (Union of Women Painters and Sculptors). Consequently, young women artists flocked to Paris in these years. As the Swiss artist Louise Breslau put it, Paris was “a motherland” for women artists (16). And apparently, a number of them brought the experience of Paris back to their home countries, acting as role models for a new generation of women artists, working, teaching, and establishing schools.

In addition to some degree of personal non-conformism and independence of mind, and their shared struggles to overcome the obstacles they faced, the tie that binds together the artists featured in the exhibition is that each of them spent time in Paris, most taking advantage of the opportunities for training there, and all profiting from exposure to the rich artistic culture of the city. Beyond those commonalities, there is great variation. Certainly, as Madeline points out in her essay, there was no unanimity among them regarding artistic approach. For example, while Emily Sartrain, a conservative painter, regarded Cassatt as “too extreme,” and deplored the latter’s “contempt” for Salon painting, Berthe Morisot considered the more conventional Marie Bashkirtseff “mediocre” (18).

One can only imagine the challenge posed by finding a rationale for organizing the variety of artists, diversity of styles, subjects, and nationalities represented over a fifty-year timespan of rapid transformation in society and the arts. The curators’ solution was to arrange the show thematically, selecting eight subject areas prominent in the art of women in this era: most are depictions of the lives of women. The loose thematic groupings, each one preceded by an explanatory placard, are sometimes truly illuminating, and at others slightly problematic. Some groupings are overly broad, or overlapping, and occasionally, examples seemed forced into groupings that they don’t quite fit.

Preliminary material, including photographs of and quotes from several of the artists, effectively sets the scene (fig. 1). Particularly poignant is a quote from Marie Bashkirtseff lamenting her exclusion from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts: “It is enough to make one cry with rage. . . . Why cannot I go and study there?” The question was soon ironically answered by an enlarged photograph of an atelier at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts where male students are studying from the nude male model (fig. 2).

The introductory theme, “The Art of Painting,” which follows these preliminaries, comprises one of the most successful groupings. It takes as its subject self-portraits and portraits of women artists at work, all painted by women, and asserts in a placard at the outset their “determination to be taken seriously as artists.” While male artists often painted themselves and their colleagues at work or in group portraits, they only rarely painted women artists at work. One eye-opening exception is the only work by a male artist included in the show, a painting of 1892 by Norbert Goeneutte of Marcellin Desboutin and his Friends at the Louvre, Before a Fresco by Botticelli (fig. 3). Off to the far right of the painting, and literally as well as figuratively marginalized, is a woman at work on a full-length copy of the Botticelli. She is neither part of the group of male artists and critics, nor is she acknowledged by them. This painting crystallizes in visual terms the exclusion of women artists from the community of their male peers, and immediately sets up a pointed contrast with the sense of community among women artists that is conveyed in their own paintings, e.g., Louise Catherine Breslau’s, The Friends (1881), Hanna Pauli’s portrait of her studio mate, The Artist Venny Soldan-Brofeldt (1886–87), or Marie Bashkirtseff’s In the Studio (1881) (figs. 4, 5). The latter depicts women at work at the Académie Julian, and is accompanied by a placard with the artist’s statement: “At the Studio, all are equal . . . we feel so contented, so free, so proud.” It is worth mentioning that the paintings in this group, and in most of the others, range in style from Academic to Realist to Impressionist. While these stylistic distinctions might be obvious to experts, and are occasionally made clear in the informative placards that accompany a large number of the paintings, some further stylistic clues might have been helpful to the general public, which, because of the re-titling of the Denver show, might be tempted to assume that all the paintings are Impressionist.

The next several, sometimes overlapping, thematic groupings all focus on aspects of women’s lives: the worlds of femininity that one might expect women to depict. Men also painted such themes, but their works are absent here, raising questions about whether or not women treated these subjects differently than their male counterparts. “Lives of Women” deals with the domestic sphere—the accompanying wall texts imply that women’s approach to this realm was unique, taking “more pleasure” in and conferring “grandeur and importance” on the private, feminine sphere and depicting with particular sensitivity the introspective life of women. Some comparisons with the work of male painters might have lent this idea interesting or more precise support. Nonetheless, of particular note in this grouping are the images of women engaged in intellectual activities, such as Mary Cassatt’s The Reader (1877), Marie Braquemond’s The Afternoon Tea (1880), and Harriet Backer’s Evening (1890), subjects rarely treated by their male contemporaries (fig. 6).

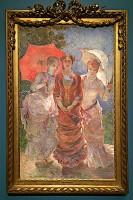

“La Toilette” in the catalogue, but more appropriately titled “La Parisienne” in Denver, is about the fashionable modern Parisienne, and emphasizes the “the act of adorning oneself for others to behold,” also treated by men and hardly a feminist subject, but here curiously elevated in wall texts as a “metaphor for painting” and a corrective to, or idealization of, nature.[2] Cecilia Beaux’s Woman with a Cat (1894) in this section, is one of the most arresting images; it is beautifully painted with an acute sensitivity to the sitter’s pensive gaze, and as such, it could equally well have been placed in the preceding group (fig. 7). Particularly interesting in this grouping, especially from the perspective of style, are Marie Braquemond’s Impressionist paintings, On the Terrace at Sèvres and Three Women with Parasols (both ca. 1880; fig. 8). Braquemond is the least well known of the Impressionist women featured in the show. An essay is devoted to her in the catalogue with much emphasis on the stultifying effects on her career of her artist husband Félix’s domineering personality and sexist ideas. Yet more could be said about her style. She seems to have developed her own unique version of the divided touch, painting with short, tightly woven diagonal strokes that form, if the dates are correct, an innovative precedent to Neo-Impressionism.

“Picturing Childhood,” the next section, is concerned with women’s images of children, and of mothers and children, subjects also portrayed by men, but perhaps treated more insightfully by women; several of them, most notably Mary Cassatt, developed an approach that was more believably realistic and less cloyingly trite and sentimental than had been customary in the representation of children. One might add that the fact that Impressionist women artists, notably Cassatt and Morisot, specialized in this subject matter is well within the Impressionist ethos of painting modern life from direct observation. Cassatt and Morisot simply explored the areas of activity available to them as women of the cultivated upper middle class: the life centered around home and family. They were not at liberty to explore the brothels, dance halls, and cafés frequented by their male peers. Of particular interest in this group is Cecilia Beaux’ Ernesta (Child with Nurse) (1894) one of the most exceptionally sensitive, and lesser known images of childhood innocence (fig. 9). Also worthy of note is the striking juxtaposition of two paintings, very similar in subject and sentiment, but starkly contrasting in style: Elizabeth Nourse’s conventionally realistic A Mother (1888) and Paula Modersohn-Becker’s primitivizing-modernist Nursing Mother in Front of Birch Forest (1905), (figs. 10, 11). The Modersohn-Becker is one of four paintings by her included in the exhibition, yet her work in terms of both time frame and style seems oddly outside the show’s purview. I suppose, however, that as a major figure, who did study in Paris ca. 1900, her inclusion could be justified.

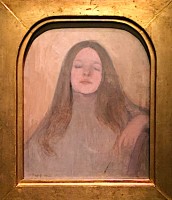

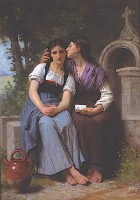

Several rooms later, following a puzzling digression to themes of landscape and history, we arrive at the final and most eccentric grouping of the show, “Jeunes Filles.” One wonders why this serves as the show’s closing theme. It might have been more appropriately placed directly following “Picturing Childhood,” as it also is about women’s lives. “Jeunes Filles” nonetheless offers a series of interesting images, in a variety of divergent styles, of what the curators describe as “girls navigating the liminal stage between adolescence and girlhood,” another phase of life which women artists would have had a special sensitivity to, “having passed through [it] themselves,” (221). The stylistic array raises the question, as does the juxtaposition of Nourse and Modersohn–Becker noted above, of whether the curators’ intent was to suggest an essentialist idea that women artists of all sorts were instinctually drawn to the same themes. The evocative paintings of Death and the Maiden (1908) by Marianne Priendlsberger-Stokes, The Schoolgirl in Black (1908) by Helene Schjerfbeck and Thyra Elisabeth (1892) by Ellen Thesleff, are all either ominous or dreamy, and belong to fin de siècle Symbolism (figs. 12, 13). They fit well with the potentially fraught nature of adolescence, but are comparable to themes also treated by contemporary male artists. Some of the less emotionally charged images by Berthe Morisot and others also can be construed as appropriate here, as can Elizabeth Jane Gardner Bouguereau’s La Confidence (ca. 1880), which depicts two girls sharing secrets (fig. 14).

However, Gardner Bouguereau’s painting is a stylistic anomaly in this constellation of largely progressive artists. Painted in the manner of her husband, the celebrated academic artist William-Adolphe Bouguereau, it has perhaps a tinge of his sly eroticism as well. Most striking, and certainly meriting further discussion, is the artist’s quote on the accompanying placard: “I know I am censured for not more boldly asserting my individuality, but I would rather be known as the best imitator of Bouguereau than be nobody!” This sad statement raises all sorts of questions about the situation of women artists vis à vis their artist husbands or male mentors, especially regarding the extent to which women in this situation had space to develop originality. Moreover, Gardner Bouguereau’s work so closely resembles her husband’s that one wonders what contributions each might have made to the other’s paintings. She also confounds the expectation that women artists must be independent and rebellious against the patriarchal establishment. One is ironically reminded here of the distinctively different and more expected reaction of Morisot, who was dismayed when Edouard Manet retouched her painting, The Mother and Sister of the Artist (1869–70).[3] Nonetheless, Gardner Bouguereau must have been quite conflicted, because following that quote is the information that “she overcame formidable obstacles to achieve artistic success,” disguising herself as a man in order to attend life drawing classes where she could study from the nude model. Like virtually all of the women in the exhibition she struggled to overcome the impediments to her professional ambitions.

Sandwiched between childhood and adolescence are landscape and history. “A Modern Landscape” is one of the most compelling themes of the exhibition. Women’s opportunities to paint the landscape were somewhat limited. The most accessible “landscapes” for them were the tamed domestic gardens of their homes, the urban parks that, as Becker explains in her essay on Marie Braquemond, were liminal spaces between the public and private spheres, and the suburban country or seaside vacation spots they frequented on family outings or holidays (55, 64–65). There are several examples of these types of landscapes by the Impressionist women, e.g., Morisot’s A Lesson in the Garden (1886; fig. 15). It was more problematic, however, for women artists to venture out into nature’s isolated or untamed spaces. Nonetheless, several paintings by Nordic women artists are the products of just such explorations. Most impressive are Kitty Kielland’s Stockkavannet (1890) and her View of Jotunheimen (1896) as well as Fanny Churberg’s Waterfall (1877) (figs. 16, 17). All are moody and evocative depictions of desolate, melancholy or intimidating aspects of nature. The Nordic women seem to have had a unique connection to the landscape; this might relate to an emerging Symbolist attitude, but it also could be a reflection of a shared Nordic sensibility rooted in the northern environment, whose dramatic weather changes, long periods of winter darkness, and summer brilliance offer considerable scope for landscape imagery. It certainly is tempting to further speculate about the national differences among the artists in the show.

“The Question of History” that follows is an extremely important category for establishing women’s competence at themes more usually treated by men, themes shown at the Paris Salons, and belonging to the highest category in the academic hierarchy. Again there is a somewhat loose assortment of styles and subjects, many treated on a large scale, and all figurative and/or multi-figured. Subjects range from a biblical academic painting by Gardner Bouguereau to typical mid-century picturesque rural genre scenes à la Jules Bastien-Lepage and Jules Breton, including Rosa Bonheur’s Plowing in the Nivernais, to military scenes by Lady Elizabeth Butler à la Ernest Meissonnier or Edouard Detaille, to Annie Hopf’s Autopsy. Not all of these might properly be called history paintings, but they demonstrate the extent to which the ‘history’ category had been expanded and diluted by mid-century. In this group, Annie Louisa Swynnerton’s large allegorical painting, Mater Triumphalis (1892), though it is not noted in the catalogue or accompanying text, must certainly have been inspired by Swinburne’s 1871 poem of the same name in which ‘woman’ is conceived as a deity before whom men must prostrate themselves (fig. 18):

Mother of man’s time-travelling generations,

Breath of his nostrils, heartblood of his heart,

God above all Gods worshipped of all nations, . . .

And the world naked as a new-born maiden

Stands virginal and splendid as at birth,

With all thine heaven of all its light unladen,

Of all its love unburdened all thine earth.

What are we to make of this painting in which a highly eroticized, full-length female nude raises her arms in a pose of sensual self-display? Though she is construed as a tribute to the sublime power of womanhood, she closely recalls many of the sexualized goddesses offered up to the viewer’s gaze in academic paintings by men. Seen through a modern lens, she certainly confounds expectations about how a woman artist might approach the nude, especially considering the fact that the artist, as the accompanying blurb tells us, was a “vocal supporter of women’s voting rights.” Conundrums like this might be probed in greater depth. Further, Swynnerton’s painting seems, like a small number of others in the show, rather the work of a novice, and as such prompts one to wonder why the curators chose to include some of these weaker works, especially because quality was an issue that was so often used against women striving to become artists. I would speculate that the curators were motivated by a desire to demonstrate that women were active in all areas of subject matter—in this case, the nude. Such choices serve to shore up aspects of their thematic approach.

Another interesting example from this group is Virginie Demont-Breton’s The Tormented (1905; fig. 19), a tragic image of fishermen’s wives receiving the dead bodies of husbands drowned at sea. The artist was the daughter of Jules Breton; she was trained by him and her work is similar to her father’s in style, though perhaps more painterly. However, she staked out her own territory in the field of rural genre by specializing in scenes of the lives of poor women on the Brittany coast, a subject her father treated only occasionally.[4] Once again, such women clearly had better opportunities for training, and this one at least did find a way to develop some degree of individuality. Moreover, she, too, was acutely aware of the plight of the woman artist. As Bolloch reveals in her catalogue essay, Demont-Breton wrote an essay, “La Femme dans l’art,” in which she declared, “‘When we say of a work of art’ that it is by a woman, ‘we understand, it’s a weak painting or a pretty sculpture.’ And when we judge a serious work that emanates from a woman’s brain and hands, we say, ‘It’s painted or sculpted like it came from a man’ . . . there is an initial bias against women’s art” (264).

There are a number of significant messages that can be gleaned from this exhibition. Among them is the impressive quality of the work of many women artists of this era, several of whom have not been written into the history of nineteenth-century art. One of the leitmotifs of the show is that women artists were the equals of their male counterparts in all areas—subjects, styles, conventional or progressive approaches, hence perhaps the curator’s decision to downplay women’s traditional specialties—flower painting/still life and to a lesser extent, portraiture (20). One might question this decision, as examples of works in these categories would have illuminated an important aspect of women’s artistic output, and brought even more paintings of high quality into the show while challenging the traditional hierarchies of subject matter. Clearly, however, the show makes the point that women participated in all the major stylistic and thematic currents of the day, ranging from academic Realism to avant-garde Impressionism and Symbolism, and more frequently to compromise approaches that modified academic Realism by adopting a looser “impressionistic” brushstroke. Another leitmotif, conveyed especially in the textual accompaniments to the paintings, is that women artists struggled for opportunities to study and make art, and for recognition.

Other general conclusions we can draw are that the large majority of women artists in this era followed conventional norms, fewer were avant-garde. It was difficult enough to have a professional career, so it is understandable that few were interested in, or willing, to take the risks radical innovation entailed. A defining theme of the exhibition is that women artists excelled at picturing women’s lives, presumably because they had a particular insight into the subject. And, since the preponderance of paintings deal with this subject matter, we might be tempted to view their art through an essentialist lens. However, contrary evidence is perhaps provided by the fact that women also excelled in “men’s” subjects; among the women were noteworthy innovators in landscape painting, and of those few who attempted history painting, a number matched the quality of many of their male counterparts.

Denver’s installation, designed by Tom Fricker, Fricker Studio, graphic designer Lisa McGuire, and interior designer Jolie Kass, is quite elaborate and attractive, with changing wall and placard colors as one moves through and among the themes. The designers have skillfully transformed the idiosyncratic layout of Daniel Libeskind’s museum addition with its sloping walls and angular spaces into an appropriate setting for this show (fig. 20). Supplementary photographs, enlarged to billboard scale, and illustrating men’s and women’s ateliers, as well as paintings hung on the walls of the Paris Salon, are instructive complements to the works exhibited (fig. 21). As a whole, the installation attempts to create for the public a sense of the Parisian ambience of the era in question. This approach, while educational, seems to me somewhat overdone. In one room, for instance, the designers have created a faux-view through French doors into a painted garden (fig. 22). This is the room dominated by Louise Abbéma’s huge painting of Lunch in the Greenhouse, exhibited at the 1877 Salon, and the entire room, with its green-toned walls, is made to appear almost an extension of the painting (fig. 23). In other rooms, red velvet curtains draped against the walls or pulled back from doorways, as if in a richly appointed upper class residence, seem rather superfluous, as do several trapezoidal plinths, on whose slanted surfaces portraits of women artists at work are mounted in an allusion to the easel (fig. 24). Likewise, an opulently furnished reading room seems designed to evoke an elegant Parisian interior (fig. 25). To my mind these additions to the exhibition are somewhat excessive and a bit distracting, though I imagine they were designed to appeal to a general public, as was Denver’s renaming of the exhibition. However, the renaming is problematic in that it implies that the show is about Impressionism and Paris, neither of which is precisely the case.

Her Paris: Women Artists in the Age of Impressionism is an ambitious and important exhibition. It has much to offer both to a general public and to scholars. It enlightens the public by raising awareness of the obstacles facing nineteenth-century women artists, something scholars have long known about. It also introduces to the public a convincingly competent body of work by women artists. For scholars of nineteenth-century art there is much of interest as well. The exhibition raises a number of compelling questions, some mentioned above, others proposed in the curator’s excellent introductory essay (17–21). Hopefully, future scholarship will explore some of these questions (as well as the work of the lesser known artists) in greater depth, with more extensive analysis, and perhaps even further informed by feminist perspectives. In any case, this outstanding exhibition does the field of nineteenth-century art as well as the general public an important service by assembling and illuminating this remarkable group of paintings and the contexts, careers, and struggles of the women who created them.

Gale Murray

Professor of Art History, Colorado College

gmurray[at]coloradocollege.edu

[1] Linda Nochlin, “Why Are There No Great Women Artists?,” first published in Woman in Sexist Society: Studies in Power and Powerlessness, edited by Vivian Gornick and Barbara Moran (New York: Basic, 1971), 480–510; subsequently reprinted in ARTnews 69, no. 9 (January 1971): 22–39, 67–71, and as Art and Sexual Politics: Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, edited by Thomas B. Hess and Elizabeth C. Baker (New York: Macmillan, 1971).

[2] On the Impressionists’ interest in women’s fashion, see Impressionism, Fashion and Modernity, edited by Gloria Groom, et. al., exh. cat. (New Haven: Distributed by Yale University Press in association with the Art Institute of Chicago, 2012).

[3] Charles F. Stuckey, “Berthe Morisot,” in Charles F. Stuckey and William Scott, Berthe Morisot, Impressionist, exh. cat. (New York: Hudson Hills Press in association with the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1987), 34–37.

[4] See, e.g. Jules Breton, The Washerwomen of the Breton Coast, 1870. Oil on canvas. Present location unknown. Artwork in the public domain; image available from: https://www.wikiart.org/en/jules-breton/the-washerwomen-of-the-breton-coast-1870.