The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Solidez y Belleza. Miguel Blay en el Museo Nacional del Prado

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

April 19 – October 2, 2016

Catalogue:

Solidez y Belleza. Miguel Blay en el Museo Nacional del Prado.

Leticia Azcue Brea.

Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2016.

64pp.; 53 color illustrations; bibliography

11.40 euros

ISBN: 978-84-8480-372-0

Miguel Blay is not a familiar name for the general public, or even for art historians, except for a very (very) small circle of nineteenth-century sculpture specialists. Active in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Miguel Blay y Fábrega (1866–1936) belonged to a generation of Spanish sculptors, whose oeuvre has been overlooked until recently. Mariano Benlliure (1862–1947), and José Clará (1878–1958) were both contemporaries of Blay to whom recent studies, catalogue raisonnés and exhibitions, have been dedicated.[1] The late nineteenth century in Spain has long been decried as an artistic vacuum in the domain of sculpture, beneath the level of artistic production in other countries such as Italy and France.[2] Sculptural production in Spain was considered far behind artistic progress in painting, a recurrent criticism of the domain of sculpture. However, these critics who have dismissed artistic personalities such as Blay from art historical narratives seem to have partly founded their opinions on a profound ignorance of the artistic production of the time. They disregarded the transnational and transatlantic ties that Spanish sculptors developed with their contemporaries, and ignored the artists’ recognition at national and international Salons and exhibitions across Europe and Latin America.[3]

Born in Olot, a town in the Spanish region of Girona, Blay was trained at the local school of drawing, whose modest renown would produce several other critically acclaimed alumni such as José Clará y Joaquím Claret (1879–1964).[4] In Olot, Blay also gained critical experience in the making of mass-produced, commercial sculpture at the talleres de arte cristiano (a factory of Christian art). Supported by his master, José Berga, he passed the exams to receive a regional grant to study abroad, and, in 1888, he left for Paris. There, he worked for two years in the studio of French master Henri Chapu (1833–91) at the Académie Julian. This connection opened the doors for him to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Beyond the formal artistic training that he received in Paris, Blay had the opportunity to see the work of contemporary French sculptors at the annual Salons, and at the 1889 and 1900 World Fairs. At the time of Chapu’s death in 1891, Blay left for Rome where he spent a year, and created Los primeros fríos (The Onset of Winter), which would be his first major success in the French capital. The group was awarded a Third class medal at the 1896 Salon des Artistes Français (Salon of French Artists), and the Grand Prix (First Prize) at the 1900 World Fair where Blay was nominated Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur. In 1895, he married a French woman, Berthe Pichard, with whom he would have five children. During this period, Blay was a regular at the Salon des Artistes Français, and was part of the artistic networks of sculptors working in Paris during the rise of Auguste Rodin (1840–1917), who organized his retrospective at the Pavillon de l’Alma near the World Fair in 1900.[5]

Blay’s creations testify to his familiarity with Rodin’s works and the Parisian artistic milieu, more so than the works of his contemporary and friend, Mariano Benlliure, who quickly established himself in Rome in 1881 before returning to Spain. Although he lived in Paris for many years, Blay never abandoned his connection with Spain, and he would regularly send works to the national exhibitions in Madrid, and the international exhibitions in Barcelona. In 1906, bolstered by his Parisian success, he moved his family to Madrid where three years later he was nominated Académico de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando (academic of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts San Fernando), the pinnacle of academic artistic success in his home country. He completed public commissions in Madrid as well as in Latin America, some of which were made in collaboration with Benlliure.[6] From 1925 to 1932, Blay was appointed director of the Spanish Academy in Rome, which marked the height of one of the most prolific and international careers among the Spanish sculptors of his generation.[7]

The exhibition Solidez y Belleza. Miguel Blay en el Museo Nacional del Prado celebrates the 150th anniversary of the birth of Miguel Blay (fig. 1). Leticia Azcue Brea, chief curator of the Department of Sculpture and Decorative Arts at the Museo Nacional del Prado, and specialist of nineteenth-century sculpture, co-organized the show on Benlliure three years ago, and is once again the leading force behind the exhibition.[8] The title of the show is borrowed from Miguel Blay’s address during his entry ceremony to the Real Academia San Fernando, the Spanish Academy of the Arts in Madrid, in 1910. “Solidez” (“solidness”), and “belleza” (“beauty”) define the sculptor’s artistic program: a sculpture can only be successful if these two principles are in harmony. Indeed, the success of this two room sculpture show in a museum widely known as the temple of the greatest Spanish painters, demonstrates the capacity of the Prado’s curatorial staff to guide and educate the viewer’s eye on the medium of sculpture and its complexities, while resurrecting one of the most famous Spanish sculptors of the first half of the twentieth century (close-up images of the sculptures can be viewed on the exhibition website).

When entering the exhibition space the visitor is welcomed by a wall text describing the scope of the exhibition dedicated to Blay’s international career. On display are the museum’s holdings of drawings, medals, plaster casts, and marble sculptures, as well as a little treasure of archival documents: the artist’s pocket diary of 1902 (figs. 2, 3). Though mentioned in the wall text, Blay’s transnational career is not emphasized in the exhibition, and the artist is presented above all in the context of his Spanish contemporaries. Locating the exhibition space adjacent to the nineteenth-century galleries constitutes a conscious choice by the curators to create a dialogue with paintings by Joaquím Sorolla (1863–1923), a friend and great admirer of Miguel Blay, and sculptures by his contemporaries, José Llimona (1864–1934) and Mariano Benlliure. The choice of navy blue for the gallery walls resonates with the elegance of Blay’s creations, and this color theme is repeated in the room 47, where Eclosión (The Blossoming of Love) is the centerpiece (fig. 4).

The exhibition’s emphasis on materiality, in accordance with the exhibition’s title, is carefully respected as not only marble pieces, but also a lifesize model in plaster are displayed in the show. In contrast with the historical tendency of downplaying, or even ignoring, the importance of plaster casts (which were often destroyed or abandoned) in museum galleries, the exhibition opens with the plaster of Al ideal (To The Ideal, 1896) at the center of the main exhibition room (fig. 5). Plaster casts constitute a faithful testimony of the artist’s creative mind, but their fragility forces museums to take strong precautions to prevent visitors from touching them. It also partially explains why Al ideal is on an elevated base protected behind a cordon. Apart from being inherently fragile as a plaster, Al ideal requires even greater delicacy as it suffered from an accident in its past. The exhibition provided an opportunity to undertake conservation work on the piece, which Sonia Tortajada, conservator at the Museo Nacional del Prado, with the help of Rocío Sánchez del Pozo, worked on for months. When the sculpture came to the Museo Nacional del Prado in 2005, x-ray images showed that the piece had suffered a significant accident affecting the base and the legs of the young girl, both of which were remade (fig. 6). Again, the importance of the physicality of sculpture takes on a key role in the exhibition, and the viewer gets the chance not only to look at pieces that marked Blay’s career, but also to understand the technical difficulties of conserving and displaying such pieces.

Al ideal is composed of two female figures, one draped in a long tunic and holding a lily, symbol of purity and virtue, in her right hand; the other a young nude girl, her empty gaze directed towards the heavens with her hands held in a manner evocative of the virgin Mary receiving the holy spirit. The body of the older woman is positioned protectively behind the girl. The idealism of this group was praised by the critics, who had previously rejected the realism of Blay’s earlier creations. Here, the artist demonstrates his capacity to use the Symbolist language that defined the works of his Spanish contemporary, José Llimona, whose sculpture Grief (1907), is placed strategically on view in the adjacent gallery. However, unlike Llimona, Blay cannot be readily identified with a specific stylistic movement, and his artistic versatility is well demonstrated in the exhibition.

Beyond the title Solidez y Belleza (Solidness and Beauty) that characterizes Blay’s conception of the sculptural endeavor, the exhibition educates the viewer on the diverse range of artistic activities of a late nineteenth-century sculptor. The show explores the interaction between plaster, drawings, and marbles, as well as different genres such as medals and sculptures in the round in which Blay engaged. While the exhibition catalogue has descriptive texts about the ten drawings in the collection of the Museo Nacional del Prado, a selection of six of them are displayed on the walls surrounding Al Ideal. These drawings are representative of Blay’s mastery of the technique, from académies to modernist drawings, made in the three places where he spent the first years of his career: Olot, his hometown in Catalonia, Paris, and Rome.

At the center of the first wall, Academy of a Man (1891) depicts a male nude standing in a three-quarter posture, and demonstrates Blay’s virtuosity in the study of anatomy, which he developed during his years of academic training in Paris (fig. 7). The drawing of the seated female nude, on the right of the opposite wall was created in 1893 when Blay spent the last year of his grant in Rome (fig. 8). The young adolescent is depicted in an almost perfect profile view. One notices Blay’s interest in volume through the play of light and shadows on the female body, as well as the contrast between the details of her face and the rough treatment of the feet. This interest in depicting precise expressions of faces through the play of light and shadow is demonstrated in the drawing of the head of a child from his time in Olot, where Blay would return after his sojourn in Rome (See fig. 7). From that same period, a very detailed and finished drawing depicts a young girl seated in an armchair (See fig. 8). Enveloped in a diaphanous robe that contrasts and covers her conservative clothing, she confidently addresses the viewer, her hands held firmly on her lap. The drawing stands as a testimony of Blay’s skill and conveys his mastery in contrasting textures and materials.

What is missing from this display, however, is an understanding of the relationship between Blay’s drawings and his sculptural practice. How did his drawing inform his sculpture? The quality of Blay’s drawings could easily mislead a viewer to believe that he was in fact a painter. His experiments with the technique of drawing demonstrate his ties with Catalan modernism, and particularly, his links to the painter Ramón Casas in the sketch of a Sleeping Man, made in 1894, in Olot (see fig. 7). Another drawing, this time of his son Jaime made in Paris in 1903 where Blay was living with his family, also shows characteristics of modernism, with the importance given to contour and the spontaneity of the line (see fig. 8). A photograph of Blay’s three children, Jaime, Margarita, and Jorge, is reproduced on the exhibition label, documenting that Jaime was the model for the figure in the drawing who is wearing the same hat.

Beyond the significance of Paris in the development of Blay’s personal life, it is difficult for the visitor to get a sense of the role played by the French capital in the evolution of the artist’s career, or how Blay’s work was shaped by his relationship with his French contemporaries. Paris is the city in which Blay had his first successes, and where he won recognition at the 1900 World Fair, receiving the Grand Prix for his group Los primeros fríos, which was created during his stay in Rome in 1892. The group, composed of a young girl laying her head against the body of an old man in a gesture of tenderness, is today at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya in Barcelona, and is featured on the exhibition label that accompanies the Niña desnuda (Nude Girl) displayed in the exhibition. The autonomous fragment Niña desnuda wonderfully highlights Blay’s naturalistic treatment of the body, developed after his years of Parisian training, and practice in drawing live models (fig. 9). The body of the young girl is precisely modeled in marble with such gracefulness that the visitor can almost feel her rib cage gently rising beneath her delicate skin (fig. 10). Were there any resonances between Blay’s sculpture and the works displayed by his French contemporaries in Paris? Was Blay’s consideration of the sculptural fragment as an autonomous sculpture borrowed from Rodin’s artistic experimentations?

While observing Blay’s sculpture and the exceptional quality of its carving, the visitor might wonder about the artist’s workshop and artistic business. Blay’s Paris diary for the year 1902, displayed in the large glass case along the back wall, might provide some answers to this inquiry (fig. 11). This pocket diary is almost surprisingly small (fig. 12). Although it figures in the exhibition catalogue, its reproduction at a much larger scale does not allow the reader to get a sense of its actual size and materiality. The fragility of the object that Blay would use to take notes of his daily expenses, allows the viewer to travel through time and get a sense of the domestic life of a sculptor in Paris at the beginning of the twentieth century. The visitor can learn from the exhibition catalogue that payments for stamps, newspapers, tobacco, and transportation costs or photographs of his sculptures, are among the expenses listed. More importantly, the diary provides a glimpse into the everyday business of the sculptor’s studio and the networks of agents participating in the production of sculptures, from the patrons to the models, the artisans, and the foundry.[9]

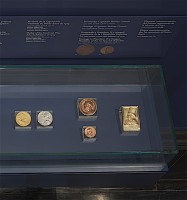

Although Blay’s transatlantic trajectory does not appear as a fundamental issue examined in the show, the presentation of two medals and a pencil drawing inform the visitor about the artist’s presence in Latin America. The two medals demonstrate Blay’s close ties with Argentina (fig. 13). In 1908, the Spanish Club in Buenos Aires commissioned him to design a medal to celebrate the club’s foundation. The large copper medal depicts an old man, wearing the beard and a toga, symbol of Spain, protecting a young man. The latter, representing Argentina, is carrying a bouquet of oak and laurel to be offered at an altar in front of the sea. The same year, Blay created a medal of an allegorical female figure wearing a cloak floating in the wind around her, surrounded by attributes of industry and labor for the Spanish Patriotic Association of Buenos Aires. The medal was released with the publication of a special edition of the journal España to commemorate the centenary of the Spanish war of independence in 1808. The drawing displayed on the opposite wall demonstrates Blay’s connections to Latin America, this time with Panama (fig. 14). It is a preparatory drawing for the group of the Atlantes soportando la bola del mundo (Atlantes Carrying the Globe), at the base of the monument to Vasco Núñez de Balboa in Panama created in collaboration with his friend Mariano Benlliure, who made the bronze statue at the top. The sketch is more the materialization of an idea rather than a descriptive drawing of the group. Sinuous and fluid lines suggest the modeling process in clay.

Examples of artistic collaboration between Blay and Benlliure can also be found in the domain of the medal. In 1915, the two Spanish masters created a medal for the Exposición nacional de bellas artes (National Exhibitions of Fine Arts) that was used until almost 1931 (fig. 13). On the recto, Benlliure made the double portrait in profile of the kings Alfonso XIII and Victoria Eugenia. On the verso, Blay depicted the figure of a crouching muse who is carrying a laurel branch and a tablet on a landscape background. Both sides of the medal are displayed in the exhibition, allowing the viewer to admire the technical skills of the two artists in the practice of medal making.

The choice of display of medals and a plaque in the exhibition is of significant interest in understanding the artistic versatility of sculptors at the turn of the century. The objects demonstrate Blay’s comfort with the technique of bas-relief while also showcasing pieces that are generally not given much visibility at most museums, although they constituted an important source of income for many sculptors. In the first decades of the twentieth century, Blay had become a renowned and sought after artist who received an important number of commissions in Spain. A selection of portrait medals of three important Spanish personalities are on display in the glass case that are representative of the many commissions Blay would receive once he was reestablished in Spain.

In 1917, Blay was commissioned to design a medal to pay homage to Francisco Pi y Margall, the President of the First Spanish Republic (fig. 15). The small size of the medal and the refined treatment of the glasses and beard of the sitter on its recto emphasize Blay’s mastery of the chisel. Its verso depicts Blay’s plan for a monument for the President—a rounded bust between two columns accompanied by allegorical groups. A copper medal from 1929 pays tribute to Ignacio Bolívar Urrutia, a naturalist and entomologist, director of the Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid and of the Royal Botanical Garden (see fig. 15). The exhibition catalogue reproduces a photograph of the sitter, which was probably used by Blay to finish the medal after his appointment as director of the Spanish Academy of Fine Arts in Rome in 1926. On the far right of the glass case, a commemorative plaquette is displayed in recognition of the first centenary of the death of Goya in 1828 (see fig. 15). It was commissioned by the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando for its new room in the museum. While in Rome, Blay modeled the profile of Goya according to the self-portrait of the artist on the cover of the series of engravings, Los Caprichos, from 1798.

While the exhibition displays artworks shown at national and international exhibitions in France and Spain, and official commissions for monuments or medals, one particular sculpture provides particularly good insight into Blay’s more personal creations. It is the funerary bust of Miguelito, the fifth and youngest of Blay’s children, whose portrait was made posthumously (fig. 16). The cause of Miguelito’s death at the age of seven is unknown, and Blay chose to depict his son with a calm and neutral expression on his face. A photograph of the father and son taken in the artist’s studio, and illustrated on the exhibition label, demonstrates the likeness of the boy in the head sculpture, with his distinctive hairstyle parted sharply in the middle into the shape of a heart. Although this was not his finest work, there is an interesting element that is easily missed; the artist chose to decorate the base of the bust with a relief of a broken sapling, snapped in half, a life ended too soon.

The exhibition continues with the sculpture of Eclosión as the centerpiece (fig. 17). The expressive sculptural group of a young man with his head on the shoulder of his lover, grasping her right arm against his body, immediately draws the attention of the passing viewer, as if they were accidentally witnessing two lovers in their intimacy. Unlike the French master Auguste Rodin, Blay depicts romantic love in a fairly traditional and uncontroversial manner. In contrast with Rodin’s The Kiss, Blay’s Eclosión emphasizes the tenderness of love rather than its more lustful aspects. Here, the female figure dominates the pyramidal composition, her back straight and her eyes closed, in a serene gesture of love. First exhibited in plaster at the 1905 Salon des Artistes Français, then in marble the subsequent year, and again in 1907 at the Exposición International de Arte in Barcelona, Eclosión was awarded the medal of honor at the Exposición Nacional de Bellas Artes in Madrid in 1908. This group also embodies Blay’s international success and recognition as it received the first prize at the Exposición international in Buenos Aires in 1910, where it was praised by the critics.

Located at the intersection between the Renaissance rooms and the nineteenth-century galleries of the Museo Nacional del Prado, Eclosión is also featured on the front cover of the exhibition catalogue. One of the greatest artistic successes of Blay’s transatlantic career, it provides the viewer with a glimpse into the artist’s studio and his artistic business. A photograph of the group taken in Blay’s studio in 1904 in Paris was placed strategically in the exhibition gallery at the same vantage point as the original photograph (fig. 18). The visitor can thus admire the group as if they were a visitor in Blay’s studio, noticing the differences between the delicate and precise modeling of the young man’s serpentine back in the photograph, and the effects of time and the elements on the Carrara marble, which spent many decades outdoors in the garden of the National Library of Spain, once the Museum of Modern Art. The group, however, still retains the power to strike the viewer for its “strength and beauty” as desired by the artist.

Eclosión as it stands in the gallery can be the starting point, or the conclusion of the visitor’s path through the show. The dialogue between Blay’s sculptures and the works of the permanent collection flow together, such that the installation could stay there permanently, as it is so well integrated into the museum’s artistic environment. The small exhibition catalogue, authored by Leticia Azcue Brea, is composed of a biographical section on the artist, followed by extensive catalogue entries on each object in the collection of the Museo Nacional del Prado. The catalogue is well documented and illustrated, and could readily serve as a guide for the viewer in the gallery.

Solidez y Belleza. Miguel Blay en el Museo Nacional del Prado is an invitation to the viewer to explore the artistic versatility of one of the greatest Spanish sculptors of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. While some questions regarding Blay’s artistic networks beyond Spain are left unexplored in the show, the catalogue essays provide a broader examination of the artist’s mobility in foreign countries. Moreover, the exhibition constitutes a wonderful example of how museum professionals today, while struggling with financial difficulties, and given the cost of sculptural exhibitions, can build an entire show only using their museum’s holdings, while allowing visitors to admire works that have never had the chance to escape from storage.

Clarisse Fava-Piz, PhD student

Department of History of Art and Architecture, University of Pittsburgh

clarisse.favapiz[at]pitt.edu

[1] Mariano Benlliure. El dominio de la materia, Madrid, Real Academia de Bellas Artes, April–June, 2013; Valencia, Centro del Carmen, July-September 2013. Exhibition co-curated by Lucrecia Enseñat Benlliure and Leticia Azcue Brea. See also Mercè Doñate, Clarà: catalèg del fons d’escultura (Barcelona: Museu Nacional D’Art de Catalunya, 1997); and Mercè Doñate, Clarà escultor (Barcelona: Museu Nacional D’Art de Catalunya, 1997).

[2] Pablo Jiménez Burillo, “Un regard espagnol,” in Oublier Rodin? La sculpture à Paris, 1905–1914, ed. Catherine Chevillot (Paris, Madrid: Hazan, 2009).

[3] Pr. Carlos Reyero was one of the first to publish on Spanish sculptors’s presence in Rome and at the World Fairs in Paris. See Carlos Reyero, “Del Gianicolo al Champ de Mars. Los escultores pensionados en Roma y las Exposiciones Universales de Paris, 1855–1900,” Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoria del Arte, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, vol. XIV (2002): 275–88. Carlos Reyero, La escultura del eclecticismo en España: cosmopolitas entre Roma y Paris, 1850–1900 (Madrid: UAM Ediciones, 2004).

[4] On Joaquím Claret, see publications by Pr. Cristina Rodríguez Samaniego. Cristina Rodríguez Samaniego, “Joaquim Claret i l’Associació d’Escultors. Una aventura efímera”, Butlletí de la Reial Acadèmia Catalana de Belles Arts de Sant Jordi, no. 22 (2008): 111–126. See also Joaquim Claret: escultor de la Mediterrània (1879–1964), ed. Cristina Rodríguez Samaniego (Olot: Institut de Cultura de la Ciutat d’Olot, 2010).

[5] Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, ed., Rodin en 1900 L’exposition de l’Alma (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2001).

[6] Blay created public monuments in Buenos Aires, Santiago de Chile, Montevideo, Panama City, and San Juan in Puerto Rico.

[7] Pilar Ferrés Lahoz did her dissertation work on Miguel Blay. See her publications: Pilar Ferrés Lahoz, ed., Miguel Blay i Fábrega 1866–1936. L’Escultura del Sentiment (Girona: Fundació Caixa de Girona, 2000). Pilar Ferrés Lahoz, Miquel Blay i Fàbrega (1866–1936) Itinerari artístic (Olot: Carme Simon editora, 2004). Pilar Ferrés Lahoz, ed, Miquel Blay i Fàbrega (1866–1936) Els anys a París (Terrassa: Fundació Cultural Caixa Terrassa, 2005).

[8] Leticia Azcue Brea co-organized the show with Lucrecia Enseñat Benlliure, a descendant of the artist and director of the foundation Mariano Benlliure: http://marianobenlliure.org.

[9] See Luis Estepa and Pilar Franco de Lera, “París y 1902: Un año en la vida del escultor Miguel Blay,” in Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoría del Arte (U.A.M.), vol. III (1991): 161–98.