The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

The development of comics from sequential narration, with a history stretching back for centuries, has been recounted often, but the parallel trajectory of comics from popular prints is virtually unknown. The modern history of comics is usually traced from caricature through the multiplication of frames, with the end result being our modern comic strip.[1]The Story of Mr. Jabot (Histoire de Mr Jabot; fig. 1) by the Swiss schoolmaster Rodolphe Töpffer (1799–1846), published in 1833, is usually cited as the first comic book.[2] If we go back slightly earlier, we find Töpffer's predecessor, Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827), whose hand-colored etchings for The Tour of Doctor Syntax, in Search of the Picturesque (1812), depict the adventures of its protagonist, and show both the humorous exaggerations and deformations typical of caricature, as well as the sequential organization of events typical of modern comics. In Figure 2, Doctor Syntax falls into a lake while sketching picturesque scenery (fig. 2); his pointy chin, beak-like nose, and ungainly limbs only increase our amusement at his pratfall.[3] Before Rowlandson there was, of course, William Hogarth (1697–1764), who produced numerous narrative print series, beginning with A Harlot's Progress of 1732 (fig. 3), which traces the downfall of an innocent country lass who arrives in London and is led astray. These three artists, Hogarth, Rowlandson, and Töpffer, are invariably cited in what has become the canonical reading of the history of comics.

Popular prints, the cheap woodcuts produced throughout Europe for centuries, are virtually ignored in the history of comics, as they are in art history as a whole, because they are assumed to be produced by semi-skilled artisans for an unsophisticated rural audience.[4] And yet we can trace a parallel trajectory for comics that leads directly back to popular prints, bypassing caricature altogether. This reading is not intended to displace one "source" by another, but rather to call attention to the all-encompassing drive to sequential narration that was operative throughout the nineteenth century in all media, eventually resulting in cinema on the one hand, and modern comics on the other.

In order to understand the transformation of popular prints into comics, some background information on popular print production is necessary. The earliest such prints were broadsides, single-sheet woodblock prints, crudely cut and garishly colored by stencils (fig. 4). They were cheap and ephemeral, intended for a semi-literate, mostly rural, audience.[5] Such prints, depicting saints, rulers, legends, and current events, had been produced for centuries all over Europe. Early printmaking centers existed throughout France, in Orléans, Lille, and Beauvais, for example, but in the nineteenth century printmaking became concentrated in eastern France. The town of Epinal (fig. 5), south of Nancy, eventually became synonymous with French popular print production and, as a result, French popular prints are often called "images d'Epinal" regardless of where they were actually produced. In Epinal the firm of Pellerin, established in 1796 by Nicolas Pellerin, was responsible for most of these prints.[6] It has remained in business for over two centuries, changing its name in 1984 to l'Imagerie d'Epinal, and operates today on the outskirts of the city, where it occupies the factory built in 1897 after its previous workshop was destroyed by fire.[7]

In its early decades, the Pellerin firm produced the full gamut of popular imagery from playing cards (fig. 6) to religious imagery (fig. 4), appealing, one might say, to both ends of the consumer spectrum. These images were usually sold by traveling salesmen, peddlers known as colporteurs, who also sold the cheap books known as the bibliothèque bleue from their blue covers, as well as almanacs, and catechisms. Colporteurs sold a good deal of pornography and politically subversive images and texts as well, all of which lent them an aura of ill repute that rubbed off on their wares.[8]

By the early decades of the nineteenth century, the predominant subjects of popular prints were religious; the prints were called images de préservation after their function of protecting the individuals who displayed them. St. Agatha, for example (fig. 4) protects against fire, St. Roch against the plague; St. Nicolas is the patron saint of sailors, while St. Geneviève is the patron saint of the city of Paris. Their images, cheap and ephemeral, formed the stock in trade of colporteurs. And yet, within a few decades, subjects like St. Agatha were largely displaced in popularity by contemporary subjects such as The Station Master's Goat (La chèvre du chef de gare; fig. 7). By understanding this transition from religious subjects to comics, we can better situate both the comic strip and the popular print within the larger context of nineteenth-century visual art production.

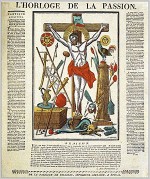

Comics shared with two earlier art forms, history painting and book illustration, the intention of narrating a story. The main difference is that history painters, limited to one static image, traditionally chose a moment of high drama to represent the entire event. Since history painting focused on well-known events from religion, mythology, or history, it wasn't necessary to show every episode in the narrative, just the principal one that could symbolize the whole. Even painters who did treat an entire narrative, such as Peter Paul Rubens in his Marie de' Medici cycle of 1622–25, now in the Louvre, in which twenty-four paintings recount the high points in the life of the Queen, chose the individual episodes carefully so that each one depicted a major event and could stand alone as a history painting. One painting, for example, depicts the moment when Henri IV first sees the portrait of his intended bride (fig. 8); another shows Marie de' Medici arriving in France for her nuptials. Early popular prints of religious subjects followed the same narrative strategy: in the 1822 Cycle of the Passion (L'Horloge de la passion; fig. 9) by Pellerin's chief designer François Georgin (1801–63), only the moment of Christ's crucifixion is shown, since its audience would know well the events leading up to it.[9]

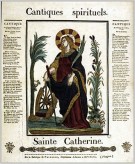

Popular images such as The Cycle of the Passion had much in common with history painting. This is not surprising since printmakers often copied well-known paintings and sometimes even copied each others' engravings after such paintings. These practices in reproductive printmaking persisted until the advent of photography.[10] A 2009 exhibition at the Musée de l'Image in Epinal, Neither Completely the Same, nor Completely Different: Masterpieces as Models, focused on popular printmakers' copies and adaptations of works of high art.[11] Examples of this can be seen in the comparison of St. Catherine Virgin and Martyr (Sancta Catharina Virgo et Martyr; fig. 10), engraved by Schelte Adams Bolswert (1586–1659) after Rubens's Raising of the Cross (1610–13) in Antwerp Cathedral, with Spiritual Canticles. St. Catherine (Cantiques spirituels. Sainte-Catherine; fig. 11), the popular print derived from it.[12] Since Bolswert reproduced the painting directly on the copperplate, his image, when printed, was reversed; the Epinal print is correctly oriented, either because it was cut in reverse or because it was copied from Bolswert's engraving and thus reversed again. Well-known paintings often made their way into the popular repertoire. Charles Thévenin's 1806 painting The French Army Crossing the St-Bernard Pass, 20 May 1800 (Passage du grand Saint-Bernard par l'armée française le 20 mai 1800; fig. 12), reappeared as François Georgin's 1831 print Crossing Mont Saint-Bernard (Passage du mont Saint-Bernard; fig. 13). Georgin's print is not reversed, nor is the 1810 engraving by Jean Duplessis-Bertaux (1747–1819) of the same subject, which might have served as Georgin's model; to accomplish this tour-de-force of reproductive printmaking, both printmakers would have had to cut their plates in reverse.

That the exhibition Neither Completely the Same, nor Completely Different was held at all is indicative of a reevaluation process familiar to art historians, wherein art formerly dismissed from the canon is first recognized as the raw material or, in this case, the secondary by-product, of high art, and only later is acknowledged as art in its own right. The art of Asia, Africa, the Americas, and the Pacific, formerly labeled "Primitive," followed this trajectory, and was recognized for its role in the development of Western high art long before it was acknowledged as having intrinsic value. This process of reevaluation, however, has scarcely begun for Western popular art production.

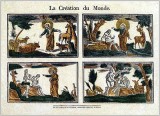

The process of transforming single-sheet imagery into sequential narration began in two ways: one was the production of stories told through a series of individual prints, each of which depicted one episode in the story. Hogarth's series are well-known examples of this practice, which parallels projects such as Rubens's Marie de' Medici series in painting. Closer to our definition of comics, however, are single-sheet images containing multiple frames arranged in more than one register on the page. Early examples of this format in popular prints tended to have religious subjects, such as The Creation of the World (La Création du monde; fig. 14), which dates from before 1814. Here, each frame depicts a different moment, from the creation of animals, to the creation of Adam, to the creation of Eve, to the temptation and fall from grace. All are crucial moments in the story.

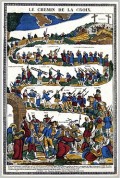

A further step toward modern comics can be seen in Georgin's 1824 Way of the Cross (Le Chemin de la croix; fig. 15), where the exclusive focus on major events that we saw in The Creation of the World in which each episode was framed like a history painting, has now been replaced by an unbroken flow of imagery that features the insignificant alongside the momentous. This shift in focus from major events alone to the inclusion of anecdotal elements spread rapidly in French popular prints from religious to secular imagery. What is often overlooked in this context is that, parallel to this shift in popular prints, there was a similar shift in history painting, from the grand narratives that emphasized major events to the inclusion of the minor anecdotal moments often featured in its nineteenth-century manifestations.

As many art historians have pointed out, nineteenth-century artists began to popularize grand-scale history painting by investing it with genre elements, small vignettes included within the depiction of the major event but subservient to it.[13] E.-J. Delécluze (1781–1863), a highly influential contemporaneous critic, blamed David's students for creating this style, which he called the genre anecdotique, and which, he claimed, had diverted the attention of the public that until then had been focused on more elevated painting.[14] Insofar as traditional aesthetic theory was concerned, this practice distracted from the impact and importance of the main subject. Evidence of the genre anecdotique can be seen in the 1804 Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-stricken in Jaffa (Bonaparte visitant les pestifères à Jaffa; fig. 16) by Antoine-Jean Gros (1771–1835), in which the group of Arab physicians on the left, and the dead and dying in the lower register of the painting, form subordinate and competing centers of interest. Such vignettes enlivened and enriched the whole and made it more attractive to the larger nineteenth-century public which, truth be told, found traditional history painting, with its moral message and its emphasis on the three unities of time, place, and action, rather boring.[15] Nonetheless, the very word vignette had a pejorative sense throughout the century, connoting an inconsequential decorative image, originally an ornament, but, later, any illustration.[16] Despite his incorporation of anecdotal elements, however, Gros's work as a whole remained focused within the context of traditional history painting, here a glorification of Napoleon Bonaparte who fearlessly touches the plague victims.

Philippe Bordes has pointed out that the problem of the growing importance of this new hybrid form of history painting, featuring anecdotal vignettes within the larger theme, became particularly acute for Gros's younger colleague, Théodore Géricault (1791–1824) who, as he lay dying in 1824, lamented that he had produced nothing but vignettes.[17] Even his great painting, the 1819 Raft of the Medusa (Le Radeau de la Méduse; fig. 17), was, to him, merely a vignette. If we look at the painting in this light, we can see that it is composed of a number of smaller episodes that can be read sequentially, from the lower register where the shipwrecked lay dead, dying or in despair, through the middle register where they are hopeful, to the upper right where salvation, in the form of a passing ship, has appeared on the horizon.

During the early decades of the nineteenth century, book illustrators were also grappling with the problem of sequential narration and the vignette.[18] This was corroborated by the artist Jean Gigoux (1806–94), a painter as well as a major nineteenth-century illustrator. In his autobiography, he recounted how, in 1835, he was approached by a publisher who wanted to bring out a new edition of Alain-René Lesage's eighteenth-century novel The Adventures of Gil Blas de Santillane (Les Aventures de Gil Blas de Santillane):

One day I was asked to do a hundred vignettes for a new edition of this marvelous book. I swear I nearly had an attack of terror. It seemed to me that I would never find a hundred subjects to illustrate. Nonetheless, I did it. Some days later, the publishers asked me to do three hundred more. Then I had to reread the book and draw more illustrations as I went along. The following week, the publishers, recognizing the pleasure that these vignettes gave to subscribers, asked me for two hundred additional drawings. In all I made six hundred, and I think that I would have been able to continue indefinitely.[19]

This experience resulted in a conceptual shift in Gigoux's attitude towards narration, from the time when he feared that he "would never find a hundred subjects to illustrate"—and here he was certainly thinking of narration in the traditional sense of history painting, depicting major events in the text—to when, after six hundred, he feels that he "would have been able to continue indefinitely." Instead of choosing a single image to represent the whole, as earlier history painters, illustrators, and popular print designers had done, Gigoux was forced to establish a visual narrative parallel to the literary text in which the story is recounted through a sequence of images, often not featuring any action at all. For example, on consecutive pages we see, first, Gil Blas's carriage stopped (fig. 18), when he is about to be arrested. Next we see the lonely prison where he is taken (fig. 19), and, finally, we see him alone in his miserable cell (fig. 20). Like Gros's Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-stricken in Jaffa and Géricault's Raft of the Medusa, the whole is understood and enriched through the accretion of narrative vignettes.

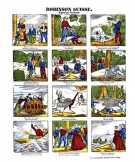

These same decades saw the vignette in all its manifestations become so widespread that Pellerin adapted it to his popular prints, producing secular narrations made up of series of broadsheet frames. Such early mass-produced broadsheets in France depicted traditional narratives that everyone knew, like Little Red Riding Hood (Histoire du petit chaperon rouge; fig. 21) of 1828. In 1830 Pellerin published the well-known French medieval legend The Story of the Four Sons of Aymon (Histoire des quatre fils Aymon), but now Georgin needed several prints of four frames each to complete the narrative; the first (fig. 22) is clearly marked "1re pl" (first plate) on the upper right. From here it was a small and almost imperceptible step to apply this same sequential narration to contemporary literature, such as Johann David Wyss's immensely popular 1812 novel, The Swiss Family Robinson (Der Schweitzerische Robinson), translated into French the following year as Le Robinson suisse. In this print of 1842 (fig. 23), the title and text are given in both French and German, a common print-making strategy that facilitated international sales.

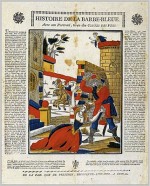

This new imperative to sequential imagery can be seen clearly by comparing Swiss Family Robinson, to the earlier Story of Bluebeard (Histoire de la Barbe-bleue; fig. 24), produced before 1811. In The Story of Bluebeard, the central image is surrounded by a lengthy text that narrates all the various episodes of the tale. In Swiss Family Robinson, this narrative function has been taken over by a series of images, each accompanied by a brief caption. Over the course of a few decades, the proportion of text to image in popular prints had been gradually reversed: the text, dethroned from its former preeminent position, had become merely a caption. The question arises, of course, as to why, in all media, one image was no longer sufficient, why multiple images were now necessary to recount a story where, in the past, one iconic and well-chosen image would suffice. The basic art historical explanation comes from the valorization of genre painting during the course of the nineteenth century. While always accepted as a category of high art, genre painting was traditionally relegated to a lower status than history painting, which, from the Renaissance, had been considered the pinnacle of art production. During the nineteenth century, however, genre paintings, by sheer force of numbers, completely overwhelmed large-scale history painting both in Salon exhibitions and in popularity. These small genre paintings, depicting even smaller moments of everyday life, were condemned by traditionalists as pandering to a new, larger art-viewing public that lacked the education to imagine and synthesize events and therefore insisted on seeing every aspect of the story, like being spoon-fed.[20] And yet, a different explanation could be proposed, one that, again, would cut across all media, and would attribute this new-found passion for multiple imagery to a shift in the sense of time, away from ideal moments to the pleasure derived from the visualization of lived experience in all its endless variety. This was the same impulse that generated the illustrated press, with new, innovative journals like Le Magasin pittoresque (1833) and L'Illustration (1843) attempting to satisfy the public's seemingly insatiable appetite for visual imagery. For in daily life we rarely experience the iconic, great dramatic moments that are the subjects of history painting, but more often a sequence of small moments that make up the fabric of our lives. It was this reflection of their own lives, and even a projection of that quotidian reality onto the historical past, that the new, greatly expanded, nineteenth-century public was avid to see represented visually, and increasingly demanded in all media—in painting, the illustrated press, popular prints, and in the new medium of comics.

So there were four stages in the transformation of the popular print into the comic strip: the traditional single-image broadside (fig. 11), then sequential narration applied first to religious imagery (fig. 14), and then to secular subjects (fig. 21). In the earlier phases of both religious and secular subject matter, literary narratives preceded the visualization of it, but in the final transformation—and here is where we might feel that popular imagery and comics flow together into one mighty stream—new stories were written and illustrated narrating the whimsical anecdotes that eventually became characteristic of comics. In Pierrot & the Moon (Pierrot & la lune; fig. 25), for example, Pierrot sees the moon reflected in his pail of water and attempts, unsuccessfully, to entrap it. Eventually, in frustration, he breaks the pail, is beaten by the pail's owner, Mme Polichinelle, and resolves never to go out again at night for fear of further "lunacy." In The Station Master's Goat (fig. 7), the station master has been told by his doctor that he must drink a bowl of goat's milk every day. He buys a goat and his wife milks it for him, but one day his wife is away, so he tries milking it himself. The goat refuses to allow it, so he puts on his wife's dress and fools the goat. While he is milking, however, a train arrives and, without thinking, he runs out on the platform to perform his station master duties in his wife's dress—to the great amusement of the passengers and—especially—the Inspector of Railways who has just descended from the train.

This final transformation of the subject matter of popular prints is most important for, at this moment, the artist is no longer adapting models already established by previous artists and writers, but has created a new art form celebrating the smaller moments of daily life: the comic strip as we know it. Just as genre painting had become, over the course of the nineteenth century, the most popular form of high art, so did comics become the popular art equivalent of genre painting.

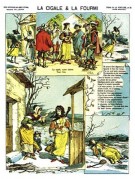

Alongside the new subject matter, however, the production of comic strips illustrating traditional literature continued throughout the nineteenth century, although the prints themselves were updated regularly to reflect new styles, and often recast into contemporary dress as well. For example, there are numerous popular prints after the fables of Jean de La Fontaine (1621–95), but, gradually during the nineteenth century, the artists who designed and cut these images, or who copied high-art imagery to the limits of their ability, were replaced by academically trained illustrators. With lithography and the photomechanical processes that were developed in the later nineteenth-century, artists were freed from the necessity of actually cutting the wood block, which further diminished the distance between designers working for Pellerin and those working for the new illustrated periodicals. As a result, E. Phosty's 1895 vignettes for La Fontaine's The Grasshopper and the Ant (La Cigale et la fourmi; fig. 26), are very similar in style to those one might find in either the illustrated press or in contemporaneous genre painting.[21] With the suppression of the guild system in 1791, the new government-sponsored art schools that had been established throughout France in the previous decades resulted in the gradual transformation of the education of artists from the old artisanal workshop model to the professional education the schools offered.[22] As a result, a higher level of expertise was increasingly available across the spectrum of art production, even for ephemeral illustration such as this. Increasingly, all artists, whether destined to be illustrators or history painters, had the same kind of basic training, focused on anatomy, perspective, and emulation of the great art of the past. This is evident in a comparison of two interpretations of The Grasshopper and the Ant. The earlier version (fig. 27) has the frames arranged in the grid format that, by this date, had been used for decades in popular print production; within the frames the figures stand squarely and frontally, their weight evenly distributed on both feet in poses that are clearly inspired by observation of daily life. In Phosty's later version (fig. 26), however, the rigid grid has been replaced by a free-form arrangement of square and rectangular frames of various sizes, within which the figures stand gracefully with weight balanced on one leg, the other slightly bent. Their poses are reminiscent of the contrapposto of Greek sculpture, the ideal of figure drawing as taught in all art schools until modern times.

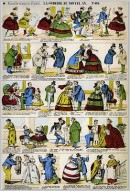

The crucial moment in the transition from popular print to comics came when François-Charles Pinot (1817–74) joined the Pellerin firm in 1847. Trained in the studio of the esteemed Parisian history painter Paul Delaroche, Pinot had aspired to a career as a history painter, but family necessity drew him back to Epinal and financial need resulted in his working for Pellerin.[23] While this might have seemed a tragic denouement for him—and certainly historians of popular prints in France have identified this moment as the beginning of the decadence of popular prints—it can also be seen as a kind of closing the circle of popular imagery.[24] Pinot had worked in Paris for the newly established weekly, L'Illustration, producing drawings of contemporary subjects. He introduced these subjects to the Pellerin firm where they coexisted with more traditional subjects.[25] Pinot's 1868 New Year's Comedy (La Comédie du nouvel an; fig. 28), produced after he left Pellerin to start his own firm, shared with popular prints the same garish coloring, but consists of five registers of unframed vignettes that follow various classes of citizens through their social rounds of wishing friends and neighbors a Happy New Year.[26] These can comfortably be called comics, although the contemporaneous term for them was historiettes, little stories.[27]

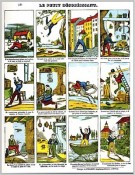

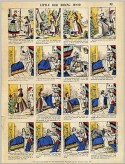

These new single-sheet comics depicted contemporary subjects for audiences of all ages. Some, to be sure, were for children, though the earliest ones for this audience were heavy on the moralizing intended to make children better future citizens. Pairing naughty adventures with dire consequences, the prints' purpose was clearly to discourage mischievous behavior, though such colorful and exuberant vignettes might well have inspired it instead. In a typical example of 1843, The Disobedient Little Boy (Le Petit Désobéissant; fig. 29), the boy falls out of a tree while trying to steal apples; he takes out a boat alone and almost drowns, and he torments bees who then sting him.

Despite such prints, we must not forget that the new, popular art form of comics was not originally intended for children, although in the twentieth century children became its principal audience. In the nineteenth century, however, most of the new comics were aimed at adults. The comic albums produced in France from the late 1830s on, by caricaturists such as Daumier, Gavarni, and Grandville, as well as by Töpffer and his French followers, were novelties, rather costly and specifically advertised as "intended to be displayed on Salon tables or to decorate the library of the book lover," as one contemporaneous publisher advised.[28]

With technological advances, larger print runs were possible, resulting in ever cheaper books, newspapers, magazines, and prints. In an effort to expand his audience, Pellerin began producing his historiettes for amusement value alone, for children and for adults, just as urban publishers churned out their albums of comics and caricatures.[29] As the Pellerin firm grew and prospered, producing ten to fifteen million prints a year in the later nineteenth century, the two audiences of urban and rural began to merge.[30]

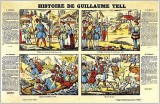

Because popular prints were usually colored—stencil-colored at the beginning of the century, chromolithographed by the end—they bear a striking resemblance to twentieth-century comics. Colored comics had not yet appeared in the periodical press, however; Richard F. Outcault's Hogan's Alley, featuring the Yellow Kid, appeared in Joseph Pulitzer's The New York World in 1895 and is generally acknowledged as the first color newspaper comic strip.[31] Black and white serial comics had appeared earlier, however. Although L'Illustration reprinted Rodophe Töpffer's Story of Mr. Cryptogame (Histoire de M. Cryptogame) in 1845, the first comic strip written and drawn expressly for the French periodical press was by Nadar (Félix Tournachon, 1820–1910), whose The Public and Private Life of Mister Reactionary (Vie publique et privée de Mossieu Réac; fig. 30) appeared in 1849 in twelve weekly installments in the Revue comique à l'usage des gens sérieux (The Comic Revue for Serious People).[32] Arranged as a multi-frame banner scrolling across the bottom of each page, as many as six such pages to an issue, it bore little resemblance, other than in its sequentiality, to the garishly colored single-sheet stories already being churned out in Epinal by the same decade. The Story of William Tell (Histoire de Guillaume Tell; fig. 31), for example, is actually closer to modern comics in appearance, despite its historical subject, than is Nadar's Mister Reactionary. While the genealogy of modern comics from caricature is unmistakable, as is apparent in Nadar's comic strip, the popular print can, just as unmistakably, claim equal rights of ancestry.

Pellerin's images were not published in newspapers, but were printed and distributed either as single sheets or in large, bound albums. Of the numerous albums Pellerin sold, his masterpiece was undoubtedly Aux armes d'Epinal, a series of over five hundred numbered prints that began publication in 1890, though many of the prints had been published earlier. They were available both in albums measuring more than twelve by sixteen inches, or as individual prints that Pellerin combined and recombined into different anthologies. By 1890 the Pellerin firm was well into its fourth generation of businessmen from its foundation a century earlier. Its print runs had grown into the millions and were being exported all over the world, translated into many languages.[33] The earlier workshop-trained artists had been replaced, in Aux armes d'Epinal, by some of the best known French illustrators and caricaturists—names like Draner (Jules Renard, 1823–1926), Benjamin Rabier (1864–1939), O'Galop (Marius Rossillon, 1867–1946) and Caran d'Ache (Emmanuel Poiré, 1858–1909). In Caran d'Ache's There Were Three Little Children (Il était trois petits enfants; fig. 32), which depicts a boyhood prank gone wrong, we can see the same concise drawing and droll humor as in his famous cartoon about the Dreyfus affair (fig. 33).

At the same time that the seemingly separate trajectories of comics and popular prints were beginning to merge in France, Pellerin produced a series of sixty plates for the Humoristic Publishing Company of Kansas City in 1893–94.[34] Prints such as Little Red Riding Hood (fig. 34) were simply images d'Epinal that had been popular in France decades earlier, with their captions now translated into English. It is ironic that, in both style and content, they were years behind what Pellerin was producing in France by the 1890s. More typical of the fin-de-siècle Epinal style is Baldaquin's Plume (Le Plumet de Baldaquin; fig. 35) whose composition had long since departed from the rigid grid pattern that characterized early sequential prints, just as its subject, a whimsical and amusing tale of a soldier whose plume caught on fire, is inconsequential and devoid of a moral message.

So in conclusion, it needs to be emphasized that many different paths brought us to comics. While urban audiences saw the birth of comic books in the 1830s, with the first publications of Rudolph Töpffer, rural audiences by that time were already familiar with colorful prints of sequential narration. By the last decades of the nineteenth century, both audiences were being served by producers of popular prints such as Pellerin—and the image d'Epinal and the comic strip had cross-fertilized and morphed into our modern comics.

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the "Comics as Art History" session of the 2010 College Art Association conference in Chicago, and at the 2010 symposium "The Artist as Author" at Parsons, The New School for Design. It is taken from a chapter in my current book-project on the beginnings of illustrated print culture in nineteenth-century France.

A note on dates: it is extremely difficult to date popular prints, as they were copied and reissued constantly. The dates given with illustrations are those of the dépot légal, even though the required deposit of one copy of all prints could occur several years after publication, if at all, so dates before 1890 should be understood only as terminus ante quem.

[1] The major study of comics remains that by David Kunzle, History of the Comic Strip, 2 vols. (Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1973–90); for early French comics, see Patricia Mainardi, "The Invention of Comics," Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 6, no. 1 (Spring 2007) http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring07/the-invention-of-comics (accessed January 31, 2011).

[2] Töpffer wrote The Story of Mr. Jabot (Histoire de Mr Jabot) in 1831, had it printed in 1833 (the date that appears on the first edition), but did not allow it to be distributed until 1835, after he had been tenured as professor at the Geneva Academy. For the complete history of Töpffer's albums, see David Kunzle, ed. and trans., Rodolphe Töpffer: The Complete Comic Strips (Jackson, MS.: University Press of Mississippi, 2007), 627–50, and also David Kunzle, Father of the Comic Strip: Rodolphe Töpffer (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2007).

[3] Rudolph Ackermann published "The Schoolmaster's Tour," a series of plates by Thomas Rowlandson with verses by William Combe, in his Poetical Magazine, May 1809 to May 1811; Ackermann then republished it as The Tour of Doctor Syntax, in Search of the Picturesque (London: R. Ackermann, 1812); there were numerous editions, and two subsequent "tours," The Second Tour of Dr. Syntax, in Search of Consolation (London: R. Ackermann, 1820) and The Third Tour of Dr. Syntax, in Search of a Wife (London: R. Ackermann, 1821).

[4] The reading of French popular prints that identified, even romanticized, them as the work of semi-skilled artisans for a rural audience was established in the first major study, written by Champfleury [Jules Husson], Histoire de l'imagerie populaire (Paris: Dentu, 1869) and was reiterated by the second major study, Pierre-Louis Duchartre and René Saulnier, L'Imagerie populaire: Les images de toutes les provinces françaises du XVe siècle au second empire (Paris: Librairie de France, 1925). The basic reference work on French popular prints is the catalogue of the holdings of the Bibliothèque Nationale and the Musée National des Arts et Traditions Populaire, Nicole Garnier, ed., L'Imagerie populaire française, 2 vols. (Paris: RMN,1990). Since all these authors concluded their studies at mid-nineteenth century, they all ignored the later developments that are the focus of this essay.

[5] See Champfleury, preface to Histoire de l'imagerie populaire, ix-l; Duchartre and Saulnier, L'Imagerie populaire, 1–24; and Garnier, L'Imagerie populaire française, 1:17–24.

[6] The history, development, and reception of images d'Epinal is discussed more fully in my article "Popular Prints for Children … and Everyone Else," Princeton University Library Chronicle 71, no. 3 (Spring 2010): 357–91. On Pellerin, see Jean-Marie Dumont, La Vie et l'oeuvre de Jean-Charles Pellerin 1756–1836 (Epinal: L'Imagerie Pellerin, 1956).

[7] Duchartre and Saulnier, L'Imagerie populaire, 190; Eric Staub, preface to Histoire de l'imagerie…une entreprise bicentenaire, by Imagerie Pellerin (Epinal: Imagerie Pellerin, 1991), 10.

[8] See Bernard Huin, "L'Imagerie à Epinal," in Images d'Epinal, ed. Denis Martin, exh. cat. (Paris: RMN, 1995), 33–67; see also Geneviève Bollème, "Une littérature perdue," in La Bibliothèque bleue: La Littérature populaire en France du XVIIe au XIXe siècle (Paris: Editions Gallimard/Julliard, 1971), 7–26.

[9] On François Georgin, see Lucien Descaves, L'Humble Georgin, imagier d'Epinal (Paris: Libraire de Paris, Firmin-Didot, 1932).

[10] For a thorough discussion of this subject, see Robert Verhoogt,Art in Reproduction: Nineteenth-Century Prints after Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Jozef Israëls and Ary Scheffer, trans. Michelle Hendriks (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007).

[11] Musée de l'Image, Ni tout à fait la même, ni tout à fait une autre, ou des chefs-d'oeuvre commes modèles, exh. cat. (Epinal: Musée de l'Image, 2009). The Musée de l'Image opened in 2003, taking over the collection of popular prints formerly held in the Musée de l'Imagerie Populaire, which was housed in the Musée Départemental d'Art Ancien et Contemporain d'Epinal.

[12] This comparison is discussed by Sevérine Lepape, "Sainte Catherine de Rubens," inMusée de l'Image, Ni tout à fait la même, 67–70. St. Catherine is the patron saint of unmarried women.

[13] See, for example, David O'Brien, After the Revolution: Antoine-Jean Gros, Painting and Propaganda under Napoleon (University Park, PA.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006), 196, 237–38.

[14] See Etienne-Jean Delécluze, Louis David, son école et son temps. Souvenirs (Paris: Didier, 1855; repr., Paris: Macula, 1983), 244; Delécluze had been a student of David but gave up painting for art criticism.

[15] Traditionalist critics such as Delécluze constantly bemoaned the public's lack of interest in history painting; see, for example, Delécluze, Louis David, 244. I discuss attitudes toward history painting in Patricia Mainardi, The End of the Salon: Art and the State in the Early Third Republic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 9–35.

[16] See "Vignette," in Alain Rey, ed., Le Robert, Dictionnaire historique de la langue française (Paris: France Loisirs, 1992), 2255.

[17] Philippe Bordes, "'L'Ecurie dont je ne sortirai que cousu d'or': Painters and Printmaking from David to Géricault," in Théodore Géricault: The Alien Body: Tradition in Chaos, ed. Serge Guilbaut, Maureen Ryan, and Scott Watson, ex. cat. (Vancouver: Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia, 1997), 132. As Géricault lay dying, he lamented that he had produced nothing; when his friends denied that, citing The Raft of the Medusa, Géricault said "Bah! une vignette!" See Henry Lachèvre, Détails intimes sur Géricault (Rouen,1870), as reprinted in Pierre Courthion, ed., Géricault raconté par lui-même et par ses amis (Vésenas-Geneva: Pierre Cailler, 1947), 267. I thank Philippe Bordes for calling my attention to Géricault's use of the word vignette.

[18] For a more extensive discussion of contemporaneous book illustration, see Patricia Mainardi, "Paths Forgotten, Calls Unheard: Nineteenth-Century Book Illustration," Van Gogh Studies 3 (2010), 163–97.

[19] "Un jour, on vint me demander cent vignettes pour une nouvelle édition de ce merveilleux livre. J'avoue que j'eux un moment d'effroi, presque. Il me semblait que je n'y trouverais jamais cent sujets de compositions. Mais, pourtant je les fis. Quelques jours après, les éditeurs m'en demandèrent trois cents de plus. Alors, moi de recommencer à lire et à croquer au fur et à mesure mes illustrations. La semaine suivante, les éditeurs s'apercevant de l'attrait que ces vignettes donnait aux livraisons, m'en redemandèrent encore deux cents nouvelles. Bref, j'en fis six cents, et je crois que j'aurais pu continuer indéfiniment." Jean Gigoux, Causeries sur les artistes de mon temps (Paris, C. Lévy, 1885), 30–31. Gigoux's illustrations were published in Alain-René Lesage, L'Histoire de Gil Blas de Santillane (Paris: Paulin, 1835); when the novel was originally published (1715–35), Lesage's title was Les Avanturesde Gil Blas de Santillane; subsequent editions modernized the spelling of Avantures to Aventures.

[20] For an excellent survey of the theory and practice of genre painting in France, see chapters 1–4 of Michaël Vottero, "La Peinture de genre en France sous le Second Empire et les premières années de la Troisième Republique, 1852–1878" (PhD diss., Université Paris - IV Sorbonne, 2009). The popularity of genre painting relative to history painting is discussed throughout my Art and Politics of the Second Empire: The Universal Expositions of 1855 and 1867 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), and my The End of the Salon: Art and the State in the Early Third Republic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

[21] Virtually no information is available on E. Phosty, though he worked often for Pellerin and signed his prints.

[22] Nikolas Pevsner gives a list of twenty-nine government-sponsored art schools in France with their date of establishment; see his Academies of Art, Past and Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1940; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1973), 142. The earliest of the regional art schools was established in Rouen in 1741,the last in Toulon and Orléans in 1786; the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris had been founded in 1648 by Mazarin as a national institution and always remained the most prestigious of the schools.

[23] On Charles Pinot, see René Perrout, Les Images d'Epinal (Nancy: Edition de la Revue Lorraine Illustrée, 1912), 120–33; Hayward Gallery, French Popular Imagery: Five Centuries of Prints, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1974), 130; Staub, Histoire de l'imagerie, 10. There has yet to be a monograph on Pinot.

[24] The major scholars of French popular imagery (Champfleury, Duchartre and Saulnier, Garnier) all conclude their studies with the adoption of lithography and contemporary imagery in the mid-nineteenth century. Duchartre and Saulnier explicitly identified the later decades as a period of degeneration; see L'Imagerie populaire, 188.

[25] Perrout, Les Images d'Epinal, 131–33; Staub, Histoire de l'imagerie, 10.

[26] Pinot started the firm of Pinot & Sagaire in 1860, but it was bought out by Pellerin in 1888; see Perrout, Les Images d'Epinal, 129; Duchartre and Saulnier, L'Imagerie populaire, 189; Staub, Histoire de l'imagerie, 10.

[27] See Denis Martin, "Emergence d'un nouveau marché: de l'histoire en tableaux aux historiettes," in Martin, Images d'Epinal, 137–42.

[28] "destinés à être jetés sur les tables de salon, ou à orner la bibliothèque de l'amateur." The advertisement for Bauger et Cie in Le Charivari, May 30, 1840, gives this suggestion for the display of albums. Bauger published and sold prints, albums, and books, and advertised that customers could even make up their own albums from his stock of caricatures. On these albums, see also Patricia Mainardi, "Des débuts de la caricature lithographique à la Restauration," in Repenser la Restauration, ed. Jean-Yves Mollier, Martine Reid, and Jean-Claude Yon (Paris, Editions du Nouveau Monde, 2005), 211–22.

[29] On the emerging market for children, see Denis Martin, "Le petit musée des enfants," in Martin, Images d'Epinal, 146–200.

[30] Between 1870 and 1914, Pellerin sold between 10 and 15 million prints annually; see Staub, Histoire de l'imagerie, 10. For annual production statistics earlier in the century, see Jean-Marie Dumont, Les Maîtres graveurs populaires 1800–1850 (Epinal: L'Imagerie Pellerin, 1965), 49–54.

[31] See John Carlin, "Masters of American Comics: An Art History of Twentieth-Century American Comic Strips and Books," in Masters of American Comics, ed. Paul Karasik and Brian Walker, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 27; Thierry Groensteen, "Le Patrimoine européen du neuvième art," in Maîtres de la bande dessinée européenne, ed. Thierry Groensteen, exh. cat. (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, and Seuil, 2000), 13.

[32] Rodolphe Töpffer's Histoire de M. Cryptogame (1845) was redrawn by Cham for L'Illustration, where it was published in eleven weekly installments beginning on January 25, 1845. The twelve installments of Nadar's Vie publique et privée de Mossieu Réac began appearing in Revue comique à l'usage des gens sérieux on March 3, 1849 and continued weekly.

[33] There is little scholarship on Pellerin's later production; Martin, Images d'Epinal is one of the few publications to even consider it.

[34] There is virtually no scholarship on Pellerin's Humoristic Publishing Company project, though it is mentioned briefly in Martin, Images d'Epinal, 157.