The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

James Ensor

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

28 June 2009 – 21 September 2009

Musée d'Orsay, Paris

20 October 2009 – 4 February 2010

Catalogue

James Ensor

Edited by Anna Swinbourne with contributions by Susan M. Canning, Jane Panetta, Michel Draguet, Robert Hoozee, Laurence Madeline, and Herwig Todts

New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2009. Distributed in the US by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers.

208 pages; 162 color and 7 b/w illus; chronology, bibliography

$60.00

ISBN: 978-0-87070-752-0

Ensor. James (art) Ensor

Edited by Laurence Madeline with essays by Anna Swinbourne, Susan M. Canning, Jane Panetta, Michel Draguet, Robert Hoozee, Laurence Madeline, Herwig Todts, and Xavier Tricot. In French. Joint publication of the Musée d'Orsay and the Réunion des Musées Nationaux.

270 pages; 250 illustrations;

€48.00

ISBN: 978-27-1185-604-6

2009 marked the sixtieth anniversary of the death of the Belgian artist James Ensor (1860–1949). That attention was paid to Ensor in Belgium as a result should not be surprising, but in New York, the award-winning exhibition devoted to Ensor's career at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) during the summer of 2009, which traveled to the Musée d'Orsay in the fall, was both the talk of the town and a wonderfully crowded testament to the growing popularity of the artist's oeuvre in the United States.[1] Ensor is both beloved and well represented in public and private collections in Belgium, but he remains less well known than many other artists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[2] Ensor's art was seen in European retrospectives at the Musée d'Orsay in 1990 and at the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Art de Belgique in Brussels in 1999, and Ensor's drawings were on display at the Drawing Center in New York in 2001.[3] However, it has been many decades since the last multimedia exhibition of Ensor's work in this country.

The Museum of Modern Art's eponymous installation of more than 120 of Ensor's works was the first major American exhibition of the breadth of this artist's output since 1951.[4] The exhibition justifiably has won a number of awards since it closed. The New Yorker magazine listed it as one of the eleven best shows in New York in 2009, and it was chosen as one of the best shows by the U.S. Art Critics Association. Although Belgian artists of the modern period remain relatively unknown to the casual museum visitor in New York, MOMA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art each own very important paintings by this artist: Tribulations of Saint Anthony (1887) and Masks Mocking Death (1888), are both in the MOMA collection (figs. 1 and 2); and The Banquet of the Starved (1915) is from the Met's collection (plate 95).[5] In addition, the Albright-Knox Museum in Buffalo long ago acquired Ensor's Fireworks (1887; plate 36). Each of these works was given prominence in the exhibition.

MOMA's summer blockbuster was curated by former Assistant Curator of Painting and Sculpture, Anna Swinbourne, with assistance from Susan M. Canning, professor of art history at the College of New Rochelle, and Jane Panetta, curatorial assistant at MOMA. Swinbourne conceived this exhibition not as a retrospective or as a purely thematic analysis of the artist's output, but as a presentation of some of Ensor's greatest hits, primarily from the last two decades of the nineteenth century, the artist's best-known period. Unfortunately, several of his most famous paintings from this period did not travel either to New York or Paris, primarily because of their size and fragility.[6]

Two huge walls in deep, saturated colors marked the entrance into the exhibition. Incorporating color tones found in many of Ensor's paintings, a bright blue wall presented a monumentalized detail of the artist's calling card, in which a group of figures rendered in black silhouette carry a casket inscribed with the artist's name and his professional designation, "Artiste-Peintre." His address, the home of his parents' mask and tourist geegaw shop in the seaside town of Ostend, was noted below. A second wall, in a reddish-orange, contained another figure, bowing with hat in hand toward the funeral procession depicted on the adjacent blue wall. On the sidewall was an enlarged black and white photograph of the artist from around 1881 playing a flute on a rooftop chimney (197). Combined, these images present an already diverse set of concerns and subjects produced by Ensor (fig. 3).[7]

If Ensor's reputation is that of an artist who painted satirical images using masks and skeletons, MOMA's exhibition elegantly demonstrated far more diversity in his subjects and techniques. Organized roughly in chronological terms, Ensor's works were also grouped thematically and by medium, with some overlaps that worked both within a single gallery and between galleries as the viewer moved through the space. The larger thematic designations were: Early Modernism; Visions: The Aureoles of Christ or the Sensibilities of Light; Drawings and Printmaking; Self-Portraits; and Satire. The first two galleries contained works associated with Ensor's early years after leaving the Brussels Academy of Art in 1880, and his initial forays into the modernist technique of tachism, the Belgian artist's response to the broken brushwork characteristic of Impressionism. The paintings from this section set up the concerns of the show in concrete terms. Ensor is remembered today primarily as a loner, satirist, as the martyred and misunderstood modern counterpart to Christ, and for his paintings of skeletons and masks, yet his subjects are quite diverse, and the many paintings and prints of his friends throughout the exhibition prove that he was anything but socially isolated. The exhibition, and the catalogue that accompanied it, furthermore presented Ensor as an artist who was always experimenting artistically and in his choices of medium, especially in the period between 1880 and 1900. That his graphic works and drawings, including collage work, were given almost as much prominence in this exhibition as his paintings is testament to their importance in his career.

Many of the early works presage Ensor's paintings from the second half of the 1880s onward. An array of landscapes, still lifes, scenes of bourgeois interiors, views from the windows of his studio, portraiture, and social realism, greeted visitors in the first galleries, devoted to Ensor's "early modernism." These works are typified by the dark, almost monochromatic tones associated with the most advanced Belgian painting of the third quarter of the nineteenth century, but which casual audiences of Ensor's art may not have known previously. Typical of this utterly Belgian visual language are Rue de Flandre in the Snow (1880; fig. 4), the portrait of fellow painter, Willy Finch (1882; fig. 5), and such scenes of bourgeois interiors as Afternoon in Ostend (1881; fig. 6), a double portrait of Ensor's mother and sister, which includes the fireplace hearth that will reappear in a number of Ensor's drawings.[8] Such scenes are juxtaposed with the first of many focal points in this exhibition, the justifiably famous The Scandalized Masks (1883) in the center of the first gallery (fig. 7). A double portrait of his mother and father, this canvas presents a family drama in which the artist's mother, in an incongruously grinning mask complete with sunglasses, confronts his father, who is masked with an almost Pinocchio-nosed face and seated at a small table with a wine bottle and glass. She menacingly carries a long object, which variously has been interpreted as a flute and a billy club. It is clear that the private narrative of Ensor's father's life-long alcoholism and the strife it caused in the household are at the core of the "scandal" of the painting's title.

Drinking and the effects of alcoholism is also the subject of The Drunkards, another painting from 1883 (fig. 8). One of Ensor's most important works of social realism, along with The Lamplighter (1880), this painting presents one of the primary concerns of Ensor's older realist compatriots, Constantin Meunier and Charles De Groux: the plight of Belgium's working class. These urban drunkards reveal Ensor's interest in physiological realism, especially in the figure facing forward whose left leg seems to spring from his chest rather than from his hip. This is not to suggest that Ensor (who had been trained in the academic tradition of painting after models and sculptures) was incapable of rendering the human body correctly. Quite the contrary: such anatomical deformation would appear to underscore the bodily transformation that can come with indigence and alcohol.

Ensor's involvement with various avant-garde exhibition societies, including his participation as a founder and early leader of Les XX (1884–1893), a Brussels-based group that helped to make that city an important arts center in the 1880s and 1890s, is explored in the third and fourth galleries. One of the highlights of the third gallery is The Oyster Eater (1882; figs. 9 and 10), a large painting of a woman seated at a well-laid table set for two, reaching toward the plate of oysters in front of her. Her absent dinner partner, presumably a man, is indicated by the empty chair on the picture plane of the painting. Perhaps more than any other painting in the exhibition, this image demonstrates that, despite his residence in Ostend, Ensor was well aware of artistic practices taking place in Paris; both Édouard Manet and Gustave Courbet used similar visual strategies to very different effect in Olympia (1863, Musée d'Orsay, Paris) and Burial at Ornans (1849–1850, Musée d'Orsay, Paris).[9] Unlike the work in the previous galleries, Ensor's palette has brightened immeasurably in these works from the 1880s, and his brushwork has become even more evanescent and less descriptive. In spite of the lightened palette associated with French Impressionism, however, Ensor's subject matter here and elsewhere is thoroughly Belgian, since so much of the Belgian cuisine hails from the North Sea. Ensor's art is also distanced from his French counterparts in that these interiors render the mundane aspects of everyday life and, as Susan Canning has suggested, they also "suggest the tension, boredom and disappointment that hover just below the surface materialism of middle-class life" (32). If the brush and palette knife work in this and other paintings evokes the brushstrokes associated with Impressionism, it is used to a different effect: in Ensor's paintings the inclusion of sharply defined details remained a key element, creating a kind of stolid materiality in his imagery. Such devotion to Flemish subjects and to a Flemish attention to detail, whether it was in the depiction of the accoutrements of bourgeois interiors, his inclusion of carnival masks, or in his use of satire, Ensor's art might be viewed as a kind of modernist Flemish self-fashioning.[10]

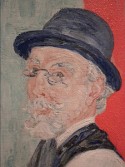

References to the Northern tradition also abound in works throughout the exhibition. If the Self-Portrait with a Flowered Hat (1883/1888; fig. 11) evokes both Flanders' greatest seventeenth-century painter, Peter Paul Rubens' and the Dutch artist Rembrandt's self portraits, the 1884 charcoal and white chalk drawing, My Portrait (1884; fig. 12) similarly echoes Albrecht Dürer's Self-Portrait (1500), and Leonardo da Vinci's Saint John the Baptist (c. 1513–1516). Ensor's pointing hand is positioned as if holding a brush or a pencil, as Herwig Todts, curator at the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp and Laurence Madeline, curator of the Musée d'Orsay version of the exhibition, both demonstrate in their essays.[11] It is also in this gallery that visitors were introduced to Ensor's habit of reworking his objects well after he had begun them. Two early examples of this phenomenon are Skeleton Looking at Chinoiseries, begun in 1885 and reworked in 1888, and The Mystic Death of the Theologian (Elated Monks Claim the Body of the Theologian Sus Ovis, in Spite of the Blessing of the Resisting Bishop Friton or Friston), begun in 1880 and reworked in 1885 and 1888 (fig. 11). In the first of these images, which also is the first of Ensor's paintings with skeletons, the artist transformed what was originally a member of his family reading in the domestic space into a fashionably dressed skeleton surrounded by the Asian curios avidly collected by Europeans at this time.[12] Regarding The Mystic Death of the Theologian, Susan M. Canning has argued that Ensor's reworking similarly shifted the meaning of the drawing from one of religious significance into one of spirituality and modern experience:

. . . figures, architectural detail, and another drawing, Ensor created a scene of feverish devotion [are] derived neither from the Bible, nor from any other religious text. Yet even with its mysterious ambiance and intricate, hard-to-decipher details, The Mystic Death of the Theologian leaves little doubt as to Ensor's master of academic quotation, skill at organizing complex composition, and ability to fill this invented world with an almost palpable sense of atmospheric light. Shimmering, flickering, forming into diaphanous shafts, or melting into a dramatic, smoky chiaroscuro, light consolidates the narrative into an evocative, visceral whole, lending a materiality to this esoteric scene that aligns it with current research on perception and discussions of the role of religion and spirituality in modern experience (34).

The roles of religion and spirituality for Ensor were explored in depth in the next gallery, devoted to most of the 1885 series of six large-scale drawings of The Aureoles of Christ or the Sensibilities of Light, and related subjects. Ensor's exploration of the symbolic potential of light through drawing was the key element in this gallery. Through the doorway to this gallery were seen The Rising: Christ Shown to the People and The Lively and the Radiant: The Entry of Christ into Jerusalem set against a blue grey wall (fig. 13).[13] Measuring 206 x 150.3 cm., this latter drawing is as large as an academic machine. If at first, the shift from the matte grey of the other walls to blue was disconcerting, it also was a design component meant to draw attention to Ensor's identification with the misunderstood and martyred Jesus. These drawings, especially the scene of Christ's entry into Jerusalem, convincingly demonstrate that collage existed long before Picasso's works from 1911.[14] Drawn from the Biblical account of Christ's arrival in Jerusalem, this drawing also evokes the contemporary turmoil of the many general strikes in Belgium during the 1880s. These drawings, furthermore, mark a shift in Ensor's work toward a more concrete and obvious political content that would echo throughout his career.[15] An outsized portrait of the social and political theorist, Emile Littré, who appears in a collaged drawing based on a photograph by the French photographer Nadar, leads the masses in the foreground. Littré was well known during the 1880s as the author of many treatises including Fragments et de philosophie positive de sociologie et contemporaine (1876), in which he discussed the problematical relationship between religion and contemporary social ills; the prominence given to Littré reinforces the contemporary relevance of this event as opposed to a rendering of the Biblical story. Ensor's teeming masses in this modern street demonstration hold or wear placards that combine Christian and Socialist slogans together with a banner of Les XX, demonstrating both the partnership—and the disparity—of joining these elements together. The aureoled figure of Christ has been pushed to the middle ground against a space aglow with spiritual light. Significantly, Christ's face is also a self-portrait, confirming Ensor's identification with Jesus.[16]

In her discussion of the Tribulations of Saint Anthony (1887), one of the many gems of MOMA's permanent collection, Anna Swinbourne argued that this painting marks an important departure from Ensor's earlier works in his abandonment of the darkened palette which had characterized his previous canvases (figs. 1 and 13). Ensor further enunciated his experiments in the rendering of light, as shown in his Aureoles series, by developing a language of color as expressive rather than descriptive (21). Swinbourne aptly writes that instead of "painting the environment around Anthony in naturalistic, earthy tones, he chose red, crimson, pink and ocher, giving heat to the throbbing scene" (21). Further evoking an otherworldly scene in this painting, Ensor included tiny demons that reference the images of the fifteenth-century Flemish painter Hieronymus Bosch and his followers (fig. 14). This referencing, and sometimes copying, of old master works is the subject of Herwig Todt's essay in the catalogue.

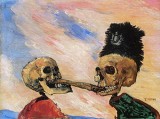

In a counterpoint to the spiritual, the next gallery was filled with Ensor's etchings, self-portraits, and many of the justifiably famous skeleton and mask paintings (figs. 15, 16 and 17). At times, his color palette in these paintings is fairly naturalistic, and at other moments, he used high pitched and garish tones. As Michel Draguet, Director of the Royal Museum of Fine Art in Brussels explains in his essay, Ensor's experimentation with and devotion to the physicality of his chosen medium is a key element in his art. Many of his images are teeming with humans and skeletons squeezed together onto the picture plane, as in Masks Mocking Death (1888), or in the huge vistas that plunge into space in the scatalogically rich colored drawings of White and Red Clowns Evolving and The Baths of Ostend, both from 1890 (figs. 18 and 19).

One of the visual elements that distinguished the installation of this exhibition from many other recent shows is the manner in which its organization allowed visitors to study the individual works in a leisurely way, and to savor the details. The brilliance of this installation is most clearly enunciated in the fifth gallery, where most of the works are given enough white space to arrest the eye and to make connections with earlier images. In this large space, several walls were given over to Ensor's extraordinary oeuvre of graphic works (fig. 20). Drawings and related prints were grouped in order to demonstrate how Ensor experimented with translating many of his subjects into different media while also documenting the unique properties of any given medium. Especially smartly installed was a huge wall of eighteen etchings from the Thomas and Lore Firman Collection, ranging in subject from portraiture and Whistler-inspired landscapes to his image of The Cathedral (1886; plate 31) which looms over the miniscule crowd in front of it, as well as the satirical, literature-based images. Organized in the salon style and grouped to display Ensor's virtuosity as a printmaker, this wall caused viewers to stop and delight in each of the small prints, and in the process, to learn about the many experimental techniques Ensor used in making his prints (fig. 21).

A documentation room complete with a biographical timeline was housed in a small area to the side of the last gallery. It was enlivened with multiple large-scale photographs of the artist from various moments in his life. This small installation also demonstrated once again the importance of photography for Ensor, both as a model for specific works, such as the two etched versions of My Skeletonized Self-Portrait (1889; plates 57 and 58). A life-long pianist, Ensor's keen interest in music, a subject that he painted as early as 1881, was also represented in this room by the inclusion of documents and drawings about La Gamme d'Amour, the ballet he wrote, composed and designed beginning in 1906 and completed in 1911 (hors catalogue).

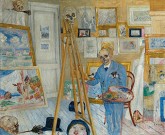

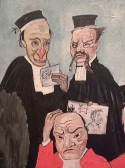

The final gallery opened with some of Ensor's best-known images of satire and ended with several later works related to imagery seen earlier in the exhibition. Here, as elsewhere, are self-portraits; Ensor seen as a skeleton painting in his studio surrounded by his oeuvre (fig. 22); in drag (fig. 23); as a herring being pulled apart by two skeletons (fig. 24); and arguing about art with a military figure (plate 71). Most famously in The Dangerous Cooks (1898), Ensor is seen decapitated, on a bed of herring, and served on a platter held by Octave Maus, the secretary of Les XX to the waiting—and already vomiting—art critics who sit in the adjacent room (fig. 25).[17] The pun on Ensor's name and profession, hareng saur (Art Ensor), the French for pickled herring, appears in many of these images. Scatalogical imagery abounds in other of the images in this room, including in The Wise Judges (1891) and The Bad Doctors (1892; fig. 26). In the first panel are evidently intoxicated judges whose faces are almost, but not quite, rendered as masks with their red noses running, reading not the legal writs but graffiti-riddled slips of paper about the evidence laid out in front of them (fig. 27). The profession of medicine fares no better. Ensor renders these men more like hapless half-wits than physicians in their misuse of a klyster and a towel left in the victim's stomach, as is noted in the texts on the floor of the scene. The figure of death, in white instead of the traditional black shroud, enters the room from the left with a comical grin on his face.

This section of the exhibition also presents some scathing critiques of the policies of Leopold II, the King of the Belgians during this period, in presenting Doctrinaire Nourishment (1889), which also was seen in the etchings section of the show, but was shown here in its hand-colored version next to the equally important attack on Leopold's political ineptitude, Belgium in the Nineteenth Century (1889; fig. 28). In addition, this gallery is filled with many of Ensor's other signature satirical paintings, including the wonderful At the Conservatory (1902) from the Musée d'Orsay in which a framed portrait of Richard Wagner holds his ears and weeps copiously at the sounds of the soprano singing the song of the Valkyries, shown hilariously and satirically in the libretto she holds (figs. 29 and 30). In each of these works, real personnages are paired with fictional ones in a kind of series of in jokes for his contemporaries and friends.

The exhibition ends with three late works related to the themes developed throughout the show. The Banquet of the Starved (1915) is a re-statement of the composition of the nearby At the Conservatory of 1902. In the later painting, created during World War I, Ensor reproduced several of his skeleton images: the 1891 Skeletons Fighting Over a Pickled Herring, and versions of his drawings of Skeletons at the Billiard Table and Skeletons Pissing, both from 1904 (fig. 31). However, in The Banquet of the Starved, the skeletal figures take on new meaning. This painting is a commentary on the physical privations that occurred in Belgium during the Great War of 1914–1918; the diners' meal consists of a few carrots, a single mussel, a paltry collection of snails and insects, and a skate, the subject of an exquisite 1892 still life that hung in the entryway to this gallery (fig. 32). Ensor's work from the 1920s is represented by a single painting, Moses and the Birds (1924), which recalls the floating demons from the Tribulations of Saint Anthony seen previously, as well as the tachiste technique, if not the palette of Ensor's earliest paintings (fig. 33). Self-Portrait with Masks (1937), poignantly presented the artist as an old man standing not in front of an easel, but in front of a group of now inanimate masks hung on the wall, rather than as characters, closed this wonderful, provocative, and important exhibition (fig. 34).

Sura Levine

Professor of Art History, Hampshire College

SLEVINE[at]hampshire.edu

[1] The Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp commemorated Ensor's death with the 2009 exhibition Goya, Redon, Ensor: Grotesque Paintings and Drawings, with an exhibition catalogue by Herwig Todts, a curator of paintings and drawings at that institution, and one of the authors of the MOMA catalogue. The Antwerp exhibition came on the heels of Todts' 2008 introductory monograph on the Ensor collection in Antwerp, which traced the trajectories of Ensor's career using their extensive collection of Ensors as illustrations.

[2] As Herwig Todts recounts in his monograph James Ensor: Paintings and Drawings from the Collection of the Royal Museum in Antwerp (Schoten, Belgium: BAI NV, 2009), the depth of this Museum's collection is due, in part, to a consistent collecting and exhibition program that began even while the artist was alive through the Antwerp-based exhibition society Kunst van Heden. The KMvSK owns more than 120 of Ensor's works.

[3]Between Street and Mirror: The Drawings of James Ensor was organized by Catherine de Zegher for the Drawing Center was reviewed by this author in the first issue of this journal.

[4] Libby Tannenbaum, James Ensor (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1951; reprinted 1966). Ensor also was the subject of a major exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1976–1977.

[5] Other American museums, in addition to the Getty's acquisition of Ensor's most important painting, Christ Entering the City of Brusselsin 1887 (1889), own important works by this artist. They include the Philadelphia Museum of Art's Self-Portrait with Masks (1937). Unless otherwise noted, all photographs of individual objects by James Ensor are provided courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

[6] Measuring some 99 ½ by 169 ½ inches, Ensor's largest and most famous painting, Christ Entering the City of Brussels in 1887 (1889, The Getty Museum of Art) is too delicate to travel. Other important absences were Russian Music (1881, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique) and Skeletons Fighting for the Body of a Hanged Man (1891, from the collection of the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp).

[7] All installation photographs are by this author.

[8] The hearth in the Ensor home appears again in a number of the artist's works, including the extraordinary collaged and reworked drawing Hippogriff (1880–1883/1886–88, plate 32) located in a subsequent gallery.

[9] Manet's painting is now housed in the Musée d'Orsay, in Paris.

[10] See Susan Canning's "Soyons Nous," in Les XX and the Belgian Avant-Garde: Prints, Drawings and Books, ca. 1890, ed., Stephen Goddard (Lawrence, KS: Spencer Museum of Art, 1992), for an in depth analysis of the Flemish element of the Belgian avant-garde and of Ensor in particular.

[11] Another source might be Courbet's early self-portraits in which the artist appears to be holding an invisible brush. See Michael Fried, Courbet's Realism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), especially "The Early Self Portraits", pp. 53-84.

[12] In the 1990 catalogue James Ensor (Paris: Musée du Petit Palais, 1990), 153, Herwig Todts persuasively argued that the appearance of skeletons in Ensor's oeuvre took place after the death of his father, an alcoholic who may have died from exposure, at the age of 52.

[13] The entire series was exhibited as a group at Les XX in 1887, the same show where Seurat exhibited Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grande Jatte (1884–86, now in the Art Institute of Chicago).

[14] Another monumental drawing from the 1885 series, The Temptation of Saint Anthony, is now in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. As Anna Swinbourne points out in her essay for the present exhibition, this drawing is composed of more than 60 pieces of collaged paper, drawn across the margins of the individual sheets (20).

[15] Belgium was governed by a constitutional monarchy and was dominated during the 1880s by the conservative Catholic Party, which had strong ties to the Pope. In 1885, the Liberal Party, whose ideology was based on an Enlightenment program of rationalism and individualism, included many of the more progressive elements in Belgium. Many of these left-leaning activists banded together to create the BWP/POB, the socialist-based Belgian Workers Party. Once the poll tax was overturned in 1892, this latter Party was able to elect, for the first time, some 28 deputies to the Parliament, thus making it possible to pass a number of important labor and other reforms.

[16] Ensor included his likeness as the figure of Christ in a number of his drawings and paintings. In addition to The Entry of Christ into Brussels (The John Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles), which most scholars of Belgian art, including many of the authors of the MOMA catalogue describe here and elsewhere as a scathing commentary on Seurat's and pointillism's great success and influence in Brussels in 1887 placed into a street demonstration, replete with comments on contemporary politics. Ensor's likeness also is found in Christ Watched Over by Angels (1886, plate 28) and Calvary (1886, plate 29).

[17] Ensor's compatriot and fellow founding member of Les XX, Anna Boch, is rendered as the hanging chicken in the kitchen of this image.