The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Alfred Stevens

Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

5 May 2009 – 23 August 2009

URL: http://www.expo-stevens.be

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

18 September 2009 – 24 January 2010

URL: http://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/vgm/index.jsp?page=161537&lang=en

Catalogue (in English, French and Dutch)

Alfred Stevens (Brussels, 1823–Paris, 1906)

Contributions by Saskia de Bodt, Danielle Derrey-Capon, Michel Draguet, Ingrid Goddeeris, Dominique Maréchal and Jean-Claude Yon

Brussels: Mercatorfonds and Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten, Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2009.

208 pages, 150 illustrations, full color

€ 29.95

ISBN 978 90 6153 8738 (English paperback)

ISBN 978 90 6153 8714 (French paperback) 978 90 6153 8745 (French cloth)

ISBN 978 90 6153 872 1 (Dutch paperback) 978 90 6153 875 2 (Dutch cloth)

This past autumn and winter, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam featured two exhibitions: the large-scale and well-attended Van Gogh's letters: The artist speaks (Van Goghs brieven: De kunstenaar aan het woord), in the context of the new web and book editions of Van Gogh's letters, and the somewhat more remote, but appealing Alfred Stevens exhibition (fig. 1). Although it may seem a slightly strange juxtaposition of the avant-garde and the academic, the work of Alfred Stevens (Brussels 1823 – Paris 1906)—born thirty years before Van Gogh and deceased sixteen years after him—is less odd in the Van Gogh Museum than one would think at first. Not only does the museum own two of Stevens' works, but Van Gogh also occasionally mentioned this Belgian artist in his letters, specifically in five letters to his brother Theo, as can be discovered effortlessly now thanks to the new letter edition.

The Stevens exhibition started in his hometown Brussels the previous summer, more precisely at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, literally at a stone's throw from the former Café de l'Amitié (on the neo-classical Koningsplein), well-known to many Belgian and foreign artists, authors and politicians, and more significantly, once owned by Alfred's grandparents; this was where the Stevens family lived with their four children (fig. 2). The Royal Museum took the commendable initiative to honour one of Belgium's most important, but somehow forgotten nineteenth-century painters with a retrospective exhibition, over eighty years after the last retrospective devoted to Alfred Stevens in Brussels (1928). The exhibition in Amsterdam was the first in the Netherlands to be devoted to the artist. It would have been wonderful if Paris had been next, as Stevens spent the major part of his life there, and exhibited almost every year in the city. However, his last exhibition there, introduced by Robert de Montesquiou, took place in 1900.

Dozens of paintings were collected for the exhibition (90 in Brussels and 64 in Amsterdam) from over thirty public and private collections in Europe and the United States, which is quite a feat.[1] As such, the exhibition and catalogue have allowed Alfred Stevens' work, always popular with private collectors and consequently widely dispersed, to be reunited for visitors to admire. This was certainly no disappointment, even though there is remarkable variation in Stevens' oeuvre and between the Brussels and Amsterdam exhibitions.

The Brussels and Amsterdam Shows Compared

In both locations, the exhibits were spread over two large rooms – out of necessity it appears, as such wide spaces are not ideal for the mostly small and intimate works. In Brussels, the ground floor hall, subdivided into a few half-open rooms by partitions, formed the core of the exhibition, with the upstairs room (somewhat hard to find) devoted to the presentation of some documents and the panorama of the History of the Century 1789-1889 (fig. 3). The latter goes pretty well there, because of the open circular form in the middle of the space, suggesting in a way the panorama's shape (fig. 39). In Amsterdam only three parts of that panorama were shown, and the paintings were evenly spread over two semi-circular rooms on different floors; the visitor was guided to and from these rooms via two wide and consistently integrated and decorated corridors around semi-circular outside space (figs. 4 and 5).

In the left corridor of the Van Gogh Museum gallery space, visitors were welcomed by an introductory documentary on a big screen, featuring Griselda Pollock and Stevens himself through quotations (10', in turn in English with Dutch subtitles and vice versa); then an introductory text situating Stevens in his historical context and pointing out his importance (fig. 6); and finally a chronological overview with key dates and facts about the artist's life, outlining the contours of his long artistic career (fig. 7).[2] In the right corridor, just before the end of the Amsterdam exhibition, quotations by and about Stevens were put on flowing drapes on the walls, among them Vincent Van Gogh's statement that: "It all comes down to the degree of life and passion that an artist manages to put into his figure. So long as they really live, a figure of a lady by Alfred Stevens, say, or some Tissots are also really magnificent" (fig. 8).[3] Copies of the catalogue could also be perused here and bought in a small shop with fitting books and objects.

The facts and quotes in the corridors gave an early indication of what a society figure Alfred Stevens was in the Paris of the second half of the nineteenth century (he had left for the French capital in 1849), and how he counted the cream of the French artistic, literary and political world, both established and avant-garde figures, among his network. Among others, his friends included Eugène Delacroix (who was best man at his wedding in 1858), the painters of Barbizon, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Adolph Menzel, Édouard Manet, Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas (who became godfather to his daughter Catherine), but also with Sarah Bernhardt, the Goncourt brothers, Gustave Flaubert, Alexandre Dumas, Jr., and Charles Baudelaire. Manet and Stevens had quite a bit in common and shared friends, models and, at a certain point, even a studio. In fact, Manet painted his Spanish Ballet (1862, The Phillips Collection, Washington DC) in Stevens' large studio. It was, by the way, in that studio where the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel first saw Manet's work in 1872—and bought two of them. They also regularly met in the 1860s and 1870s in famous Parisian cafés, such as Guerbois and Tortoni, as well as on Wednesday evenings at the Stevens' residence. At Manet's funeral in 1883, Stevens was one of the pallbearers, along with Claude Monet and Emile Zola.

Both Brussels and Amsterdam saw fairly daring experimentation with color, based on Stevens' use of colors and the atmosphere in his works. The artist paid much attention to the harmonious use of colors, patterns and light in order to carefully match his interiors and the characters and accessories in them. In Brussels, the petroleum-blue walls were inspired by a Chinese vase from Stevens' studio, which also was featured in the exhibition (fig. 9). In combination with the shiny white floor, however, the rooms came across as fairly cool in comparison with Stevens' sweetish-warm, intimate salons. In Amsterdam, the designers had the advantage of working with the warmer coloration of wooden floors, which on the basement level were combined with a straight wall in dark ultramarine blue and a curved wall in light blue (fig. 10); and on the ground floor with a bright red for the curved wall and soft pink for the straight wall (fig. 11).

The Amsterdam designers opted for a full textile cover for the walls that heightened the warm and boudoir-like effect. The straight walls were 'clothed' with vertical taft/japonette panels, the curved ones with molton, and the entrance spaces and staircases with transparent veils (hinting at women's underwear?) in the same colors, from pink to dark blue (fig. 12). Apart from that, both the columns in the middle of the exhibition spaces and the pouffes on the ground floor got matching covers, made from silk with embroidered flowers, respectively in orange and beige/olive hues (fig. 13). These luxurious fabrics matched the many shiny dresses, tablecloths and wall hangings in Stevens' canvases pretty well. Moreover, the entire impression was slightly theatrical, which were not out of place as a setting; Stevens was a frequent and enthusiastic visitor in the Paris theatres and was a close friend of star actress Sarah Bernhardt, who is represented by two portraits.

In both Brussels and Amsterdam, visitors were greeted at the start of the exhibition by Alfred Stevens, as portrayed by Gustave Courbet and Henri Gervex (fig. 14). [4] In Brussels, Courbet's portrait was accompanied by a description of the artist featured in Gil Blas and adopted in 1893 by the Brussels L'Art Moderne (fig. 15). Subsequently, the paintings were hung thematically (and up to a point chronologically) in both locations, even though the themes were only mentioned and explained explicitly in Amsterdam (fig. 16). In Brussels, it was up to the visitors to recognise the themes. There, visitors could saunter undisturbed through the exhibition, enjoying Stevens' virtuoso skill while reading some quotations on the walls. The Amsterdam approach, more educational in organization, seemed to appeal more to the visitors, with its explicit thematic arrangement and even a short clear notice for each painting, focusing on either an iconographic detail, the history, reception, or formal characteristics of the particular painting, or the broader context. As such, visitors could enjoy the magnificent dresses and interiors, while also getting a background story and a context. In order to understand Stevens' oeuvre today, that artistic, historical or social context (e.g., the role of women during the Second Empire) seems to be indispensable.

In addition to the cultural context provided by the exhibition catalogue, there were also historical documents presented in four display cases on the upper floor in Brussels (fig. 17). Among them were letters by Alfred Stevens, as well as an invoice dated 1858 from the Paris couturier Hoschedé Blémont & Cie for an Indian scarf (bought by Alfred as a dowry) costing as much as 1200 francs. Similar shawls frequently feature in Stevens' paintings as a sign of wealth. The invoice was addressed to Monsieur Alfred Stevens, living at the time in rue de Laval. There was also a personal invitation, dated 1859, from the influential Count De Nieuwerkerke to attend his famous soirées on Friday evenings at the Louvre (the Stevens brothers were also invited to the salon of his mistress, the Princess Mathilde); official honours (the French Légion d'Honneur and the Belgian Ordre de Léopold); and photos of the retrospective Alfred Stevens exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Brussels in 1907 (fig. 18). It is a pity that these documents, which were only on display in Brussels, were not allowed to play a bigger role, for instance by providing transcripts and some background.

The Themes

The themes around which the Amsterdam exhibition was structured clearly and consistently, and which also served to more or less determine the position of the paintings in Brussels, were the following: realism, visiting, motherhood, studio, interior with lady, exoticism and japonisme, mirrors, femmes fatales, seascapes, and finally, the panorama. Although some paintings could fit into more than one of these themes, they offer a convenient approach to and a representative view of Stevens' oeuvre.

(Social) Realism

The portrait of Alfred Stevens by Gustave Courbet at the beginning of both exhibitions made for a beautiful transition to the four social-realist works from the early period of the artist (fig. 19). When the young Stevens made his debut at the Brussels Salon in 1851 with four fairly traditional historical pieces—he had been trained in the academic tradition by, among others, François-Joseph Navez, Joseph Paelinck and Jean-Baptiste Van Eycken—Courbet also exhibited his Stone-Breakers. The French Realist's work inspired Stevens; between 1845 and 1857, he also focused on contemporary hard daily life as a subject. At the 1853 Paris Salon, for instance, he showed drunken carnival-goers returning home; at the 1855 Paris World Fair, he made his breakthrough with What is called Vagrancy or The Hunters of Vincennes (Musée d'Orsay, Paris).

The fact that, as a beginning foreign painter, he had some success with these (both works were bought) probably had more to do with his skills than with the choice of subject. The emperor Napoleon III thought the contents so shocking (a woman giving a beggar money to prevent her being locked up with her child by the police—the fate of vagrants without income) that he asked Count de Nieuwerkerke to have it removed, even though Stevens had few or no political intentions. Stevens did attach much importance to the tradition of Flemish and Dutch (genre) painting, and held a great admiration for the technical precision, the unparalleled reproduction of fabrics, and the symbolism of the early Netherlandish painters, and for the work of Johannes Vermeer. In reviews, this earned him comparisons with some highly respected old masters (e.g., Gerard Ter Borch), a fairly common practice in the second half of the nineteenth century that was linked to the rise of national 'schools'. Yet even though Stevens lived the major part of his life in Paris, the French critics still considered him a Belgian, indebted to the rich artistic heritage of the Low Countries. Charles Baudelaire, for instance, called Stevens a Flemish painter because he excelled in the imitation of nature—but he was fairly condescending about this.

Visiting

Around 1854 Stevens evolved from social realism towards a realistic painting of the sophisticated woman in her milieu—his favourite subject, which would eventually become his trademark. New was that they are not mythological or historical female figures or portraits, but contemporary women who dwell in luxuriously decorated salons or boudoirs, almost like precious 'objects'. Mostly, Stevens paints them on their own, but sometimes they are in the company of other women, as can be seen in the four paintings in the Visiting theme (fig. 16). Indeed, one of the main activities of bourgeois women was visits to ladies of their own class and family, and the weekly reception of visitors in their salons, which they richly decorated. In The Painter's Drawing Room (1880, private collection), sold by Stevens to the American collector Vanderbilt for the irresistible amount of 50,000 francs, we can see the excessive way in which the painter—and his wife—had decorated their own house (fig. 13).

Motherhood (fig. 20)

Apart from the 'tasteful' decoration of the interior—a construct of nineteenth-century bourgeois femininity and masculinity—and the reception of visitors in those surroundings, motherhood and looking after the family were seen as the key roles of 'respectable' women of the higher classes during this time period. Stevens also shows his women in the roles of 'trophy wife' and (young) mother. This separation of the spheres, with the place of women indoors as 'angels in the house' and of the husband outdoors as the provider, is clearly pictured in Family Scene or Domestic Happiness or All the Joys (c. 1883-1885, Musée d'Orsay, Paris), in which the woman is portrayed with a child on her lap while the husband is at work at his desk, surrounded by books, with his back to the viewer, and a window to look outside (fig. 21).

A Mother or All the Joys (1861, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels) shows Stevens' own wife, the Parisian Marie Blanc, while she is nursing their firstborn.[5] The painting was immediately bought by the advisor to the Belgian king Leopold I, whom the child was named after. Near the top of the cradle there is an image of the Virgin Mary with the baby Jesus, the archetype of motherhood. Looking at these women, however, one cannot avoid the impression that they do not all really radiate the 'joy' and happiness suggested by the titles of the paintings.

Studio

The role of women depicted by Stevens in a series of studio scenes, four of which were to be seen in the exhibition, is different. Models tended to have a doubtful reputation, as they were kept by one or more rich lovers, such as the demi-mondaines or cocottes about whom Emile Zola wrote. These women did not even differ so much from the femmes honnêtes or 'respectable' women in their appearance and lifestyle, but their reputation and situation was considerably less comfortable; together with their youth and beauty, they also lost their source of income in time. In his cartoon La Cocotte jaune (1870, reproduced in Amsterdam on the case label), in which he alludes to Stevens' painting A Painter or The Studio (c. 1869, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels), Louis-Joseph Ghémar suggested that the action and expression of the model showed her to be a lady of easy virtue (fig. 22). This picture also prominently shows Pieter Brueghel the Younger's painting, The Census at Bethlehem, in Stevens' possession, as well as some valuable furniture and precious objects. Artists often not only equipped their studio as a place of work, but also as a reception area designed to impress potential customers. Through such works of 'the painter and his model in the studio' – a popular subject in the late nineteenth century, the viewer is allowed insight into the place where the works of art were created, and gets an idea of the social status and tastes of the artist.

Interior with Lady

Half a semi-circular wall (thirteen paintings) on the basement level in the Van Gogh Museum (fig. 10) and roughly two walls in Brussels (almost twenty canvases) (fig. 23) were reserved for Stevens' forte: single female figures in fashionable dresses of the finest fabrics, lounging—silently and in various states of mind—in rich, intimate interiors. This part of the exhibition comes close to echoing the eighteen pieces that formed Stevens' definitive breakthrough at the 1867 Paris World Fair, described by a critic as "eighteen chapters from the life of des femmes de qualité." Stevens painted them with considerable empathy, and often with a slight 'catch'. He didn't just show their outward glamour, but often also their boredom, fatigue, melancholy, frustrations or unfulfilled passions and desires, shattering the idyll of their luxurious interiors. Seldom do these rooms have windows; they are huis clos, golden cages, inner spaces in which the inner self of these 'desperate housewives'—be it bourgeoises or courtesans—is noticeable.

Apart from a few exceptions, such as the portraits of Sarah Bernhardt and Eva Gonzalès, these paintings do not represent specific bourgeois women, but anonymous models embodying certain types. They are depicted smelling a flower, lying on a couch, or reading a letter, as with Vermeer. Vincent Van Gogh did not find Stevens' women very interesting: "Stevens doesn't satisfy me because his women aren't those whom I personally know anything about. And I think that he doesn't pick the most interesting there are."[6] Charles Blanc described them as being caught in an interior, frantically doing nothing. Indeed, receiving visitors and playing music, considered a virtuous and useful accomplishment for ladies as were drawing skills and embroidery, were among the main home activities of women of the upper classes. Stevens depicted several of them playing the piano, the harp or the violin, or singing, which were regarded as appropriate for women; because an elegant pose was considered important in the better circles, the cello or wind instruments were excluded. Even though there were women who performed professionally, and others who would have been able to do so, most performances were limited to the home environment. It is there that Stevens depicts them, for instance, in A Musician or The Woman in Green or The Harpist (c. 1870, Szépmvészeti Múzeum, Budapest), The Prima Donna or A Passionate Song (before 1873, Musée national du Château de Compiègne, Compiègne), The Cup of Tea (c. 1874-1878, Musée royal de Mariemont, Morlanwelz) (fig. 24), or Eva Gonzalès at the Piano (1879, The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Florida) (fig. 25).[7]

Contemporaries could tell by the clothes which time of day or which occasion was being depicted. A wealthy woman, indeed, would change several times a day. A nineteenth-century viewer would have known from the corsage, the evening dress and the cashmere shawl in Without Hope (c. 1873–1875, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp) that this woman was about to go out, or that the women in A Cup of Tea were waiting to go to a ball (fig. 24). A critic interpreted the sleeping woman in Nonchalance or The Visit (c. 1865–1869, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas) as being a 'fallen woman' because she is still wearing morning dress even though her visitors are already arriving (fig. 26).

In a way, Stevens was the fashion photographer of his time, with a preference for haute couture. That he could paint such a rich variety of expensive dresses was largely due to the fact that he borrowed dresses from Pauline von Metternich, the influential wife of the Austrian ambassador and promoter of the English haute couture designer, Charles Frederick Worth. As such, the paintings are real mise-en-scènes or constructions, in which the models were not the owners of all those exquisite gowns, but probably marvelled at being allowed to put them on, just as many a viewer nowadays does at seeing them.[8] Stevens' paintings give a marvellous image of the opulent dresses and surroundings of the upper classes. They have been depicted with an exceptional eye for the different fabrics such as silk, velvet, muslin or cashmere and materials, such as shiny gold, and with astonishing technical virtuosity. Maxime Du Camp reproached Stevens for having a 'fabric mania,' and even Félicien Rops, who was hardly a fan of Stevens, remarked that anyone who wanted to learn to paint should go to him.

Also, the objects depicted in the paintings send women—both then and now—into daydreams about (absent) lovers or different locations. The trinkets handled by the women, or decorating the interior (knick-knacks, flowers, vases or letters), determine their state of mind and add subtle meanings. In an essay on Stevens' Memories and Regrets (c. 1873–1875, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts), Count Robert de Montesquiou was convinced that one could read someone's state of mind in their face and the objects in their surroundings. The rose in The Bath (1873–1874, Musée d'Orsay, Paris) could be viewed as a symbol of love and beauty, whereas the tap in the shape of a swan neck might refer to the classical myth of Leda and the swan, adding an erotic subtext to the painting (fig. 27). In The Present or Temptation (c. 1865, National Gallery, London), the pansy (pensée in French) held by the woman (which had apparently fallen from the note she is holding in her left hand) is probably a symbol of faithfulness conveyed by the sender (fig. 28). Letters, in combination with the pose and expression of the woman, are often telling in Stevens' work. The nineteenth-century viewer would probably have known enough from suggestive titles such as Upset (1867–1868, Musée d'Orsay, Paris) and Without Hope (c. 1873–1875, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp), from the pose of the women and the letters in their hands to read the paintings as stories of women (demi-mondaine or not) who had been jilted by their lovers.

Exoticism & Japonisme

Stevens also had 'his' women dream of faraway places through letters and objects, as in The Globe or News from Afar (c. 1865, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore), in which a dreamy woman, hand on her heart, is looking at a far country on the globe, probably the country where the letter originated. Stevens often depicted exotic objects, such as the oriental tiger in The Present or Temptation. On the ground floor at the Van Gogh Museum, no fewer than fourteen paintings and two oriental objects from Stevens' studio illustrate his fascination with Japanese and exotic knick-knacks and furniture (fig. 29). He shared this interest early on with James McNeill Whistler, and later with many of his contemporaries, especially after the world fairs in London in 1862 and in Paris in 1867, where Japan showed its art and objects for the first time.

Stevens also liked to frequent Siegfried Bing's shop, and even made a Chinese room in his house with furnishings from the imperial palace in Beijing. He was an eclectic collector who filled his home with furniture, screens, parasols, kimonos, masks, fans and other accessories from several periods, styles and countries, as shown in A Duchess or The Blue Dress (1872–1873, Sterling and Francine Clarke Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts) (fig. 30). In The New Ornament or India in Paris, the Exotic Trinket (1865–1866, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam), he even combines a Japanese screen with a Persian carpet and an Indian sculpture of an elephant (fig. 31). This object, made of wood, ivory, and colored glass, and a small Chinese vase were on display both in Brussels and Amsterdam, respectively, in one and two display cases near the paintings in which the objects feature. The small vase can be seen in The Lady in Pink (1866, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels), which also shows a cabinet combining neo-baroque curls with a Japanese lacquered panel (fig. 32).

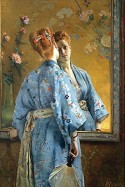

A similar combination of styles and cultures is also present in the clothing of the women depicted by Stevens. The model in A Japanese Parisienne (c. 1872, Musée d'Art Moderne et d'Art Contemporain, Liège) is wearing a blue kimono as a dressing gown revealing just a bit of French lingerie (fig. 33). The Japanese belt, a soft green obi, is not worn according to the complex Japanese wrapping technique, but loosely keeps the kimono closed. In terms of format too, Stevens was influenced by Japanese prints, characterised as they are by two-dimensionality, cuts, color contrasts, and a simple color palette, as in Upset or The End of the Affair or The Letter of Rupture (c. 1867–1868, Musée d'Orsay, Paris) or in Nonchalance or The Visit (c. 1865–1869, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas). The background divided into planes in the latter painting inspired Louis Ghémar in 1870 to have both women in his cartoon merge into the Japanese screen (fig. 26).

Mirrors

Three paintings that could also belong in other categories were put together in the theme of 'Mirrors,' in order to point out the fact that Stevens loved to use mirrors and openings, creating a game of 'watching and being watched.' The mirrors do not just allow the viewer to look at—or spy on—the women from different angles, as in Memories and Regrets, but the women themselves also sometimes peek and peer at the viewer from their salons or boudoirs, as we can see in Young Girl looking at Herself in a Mirror (c. 1875–1880, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam).

Femmes Fatales

Next, five canvases were grouped under the title 'Femmes fatales', a category in literature and fine arts then often contrasted with so-called femmes fragiles (fig. 34). Stevens mainly painted the latter category, but that did not stop him from representing some well-known 'dangerous women' or seductresses from literature and the Bible, such as Lady Macbeth (1888, Musée des Beaux-Arts et de la Céramique, Verviers, Belgium) and Salomé (1888, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels). He also depicted a few allegorical or anonymous women in a seductive way, such as Electricity (1880, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nice) accompanied by bats and a black cat; or The Lady in Yellow or Remember (1863, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels), both redheads (fig. 35). The final one, used for the strong campaign image, looks straight at the viewer, just like the equally red-haired courtesan, Victorine Meurent, in Manet's controversial Olympia.

Seascapes

When Stevens was diagnosed with chronic bronchitis in 1880, possibly due to breathing in paint fumes for years, his doctor advised him to seek out the sea air. He would spend more than fifteen summers at the Normandy coast, among others in Le Tréport, a popular seaside resort among the Parisian bourgeoisie, and on the Mediterranean coast. During that period he was faced with debts, in spite of a contract with an art dealer who offered him 50,000 francs for his entire production of the season.

At the seaside, Stevens painted his usual fashionable ladies, against the background of the sea, the dunes or country houses, but later also the sea in its own right, sometimes at night, as in the quasi-abstract Nocturne on the Sea (1886, private collection), reminiscent of the series of Nocturnes by his friend Whistler (fig. 36 - third from the right). The hundreds of marine works of varying quality not only differ from the rest of Stevens' oeuvre in topic, but also in form. Apart from small oil paintings, he also made pastels on paper after 1886, and apart from classical, almost Dutch-style works, there are also works with a looser, impressionist element (fig. 37). Yet Stevens was not very interested in impressionism and the representation of a fleeting image or moment in time.

The Panorama of History

Concluding the exhibition in Brussels and Amsterdam, but presented more extensively in Brussels, was the panorama History of the Century 1789-1889, a grand joint project with the painter Henri Gervex (1852–1929), who had come up with the idea in 1883 and mainly worked on the poses and facial likenesses. Stevens focused on the ladies, the decorative elements and the finish, in cooperation with fifteen assistants. The original work, exhibited at the 1889 Paris World Fair in a specially constructed rotunda in the Tuileries Gardens, was truly monumental: it was 20 meters high (65 ft.) and had a circumference of 120 meters (nearly 400 ft.). The panorama depicted over 660 identifiable, life-size famous figures from one hundred years of French history between the Revolution and the World Fair. Soon after the end of the Exposition, the rotunda was pulled down; the panorama was cut up into 65 pieces and divided among the shareholders of the Société de l'Histoire du Siècle. Only two thirds were preserved.

A large surviving piece (Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels) prominently shows the then legendary, but now all but forgotten, painter Ernest Meissonier, with Emile Zola behind him (fig. 38). Another part (Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, Paris) shows Alexandre Dumas Jr. and the actresses Rachel and Sarah Bernhardt, while a smaller-scale preliminary study at the exhibition features Marat's murderess, Charlotte Corday.

Luckily, we can still form an image of the complete panorama by means of the twelve heliogravures (1889) made by Dujardin, and based on photographs of the original panorama by Pierre Petit; and also by means of the four-part smaller replicas (Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels) made by Stevens, and also signed by Gervex 'for courtesy's sake.' These replicas, which Stevens tried to sell in 1897 when he was in financial trouble, via letters to Robert de Montesquiou and Max Sulzberger, were on display at the exhibition in Brussels, along with the heliogravures and the numbered identifications of the figures depicted underneath (fig. 39). On the wall opposite in the Brussels exhibition, a series of recently acquired preliminary sketches and studies were shown, among which the most important painters of the School of Barbizon can be seen: Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, Camille Corot, and Eugène Fromentin, but also, for instance, Courbet, Antoine Louis Barye, and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux.

Catalogue and Contribution

The richly illustrated catalogue seems mainly a Brussels initiative, and comprises seven articles by six authors, approaching Stevens and his work from different angles, but not providing much detail on the actual paintings. Danielle Derrey-Capon, composer of the exhibition together with Dominique Maréchal, contributed the lengthy opening article, which is a detailed chronological overview of Stevens' life that uses source materials almost exclusively from Belgium; and a second essay on fashion and interiors, entitled "Bourgeois exoticism. How to stage a lady." Jean-Claude Yon contextualises the figure of Alfred Stevens in terms of Parisian society and culture, referencing the entertainment business, music, cafés, world fairs and panoramas. General manager of the exhibition, Michel Draguet, who initiated the show together with Edwin Becker of the Van Gogh Museum, describes Stevens as a modern painter in an article on "Capital and setting," focusing on texture, fashion, and knick-knacks. Saskia de Bodt, who previously wrote about Brussels as an artists' colony of Dutch painters between 1850 and 1890, elaborates on Stevens' fascination with, and indebtedness to, the old masters of the Low Countries, and on the role of those old masters, the Golden Age, and genre painting in the reception of Belgian and Dutch painters in the second half of the nineteenth century, specifically Stevens. Dominique Maréchal, curator of nineteenth-century art at the Brussels museum, situates the early social-realist works of Alfred Stevens in relation to the miserabilist dog scenes of his elder brother and inspiration, Joseph Stevens, in relation to Courbet, and the 1851 Salon in Brussels, and the 1853, 1855, and 1857 Salons in Paris. In addition, Ingrid Goddeeris focuses on two important exhibitions in Brussels, in 1850 and 1880, in which the three Stevens brothers—Arthur as an art dealer—participated.

The essays are followed by a list of exhibited works that are neither chronologically nor thematically arranged, but follow their mention in the essays, which is not very useful. However, the variety of provenances is striking, and there is a list of the most important exhibitions in which Stevens participated (with seven as the minimum number of works, and about 200 as the maximum). There is unfortunately no index, and the 'concise bibliography' is very concise indeed, with the promise of a more extensive bibliography to be included in the fifth cahier (published by now) of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. This is anything but practical and almost forces researchers to buy this second book devoted to the panorama of the History of the Century. The cahier is certainly interesting, but there is a considerable overlap with the catalogue, as almost half of the book again consists of an extensive biography of Stevens by Derrey-Capon, this time with more fascinating quotations, more elaborate footnotes and archival materials, but yet again hardly any from Paris where the artist spent most of his life. Only the second half of the book is about the Gervex and Stevens panorama, with a text by Derrey-Capon on its origins, and a more general article by Alain Dierkens on the history and impact of the panorama as a didactic aid becoming all the rage in the nineteenth century.

The principal contribution of the exhibition and catalogue is that it has dusted off Alfred Stevens again, and that his works can once more be seen up close and in large numbers. The exhibition, however, did not fully succeed in persuading the public of the prominent position of Stevens as an artist in the second half of the nineteenth century, in between Courbet and Manet, as Griselda Pollock phrased it in the documentary. It does suffice, though, to go through the catalogue and cahier to really marvel not only at Stevens' works, but also at whom he counted among his friends and acquaintances. The figure and the oeuvre of Alfred Stevens and his contemporaries still offers much scope for research, the path to which has now been opened up again.

Marjan Sterckx, Ph.D.

Professor in Art History at Ghent University and PHL University College, Belgium

marjan.sterckx[at]ugent.be

[1] Some paintings were only to be seen in Brussels and others only in Amsterdam. In the catalogue these are indicated with asterisks within the list of works on pp. 199-203.

[2] In Brussels, the chronological overview was the start of the exhibition. The documentary was shown in the upper room on a television screen behind a wall, alternately in Dutch and French, without subtitles. All texts appeared in French and in Dutch in Brussels, whereas the communication in Amsterdam was bilingual English-Dutch.

[3] Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, inv. nos. b444 a-b V/1962, Br. 1990: 503 | CL: 406: Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Nuenen, Monday 4 and Tuesday 5 May 1885. http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let500/letter.html ("Het ligt maar aan de mate leven en passie die een artist in zijn figuur weet te geven, als 't maar goed leeft dan is een damesfiguur van Alfred Stevens b.v. of sommige Tissots ook wel degelijk prachtig.")

[4] In Brussels Gervex‘s portrait of Stevens was on the first floor, with the panorama of the History of the Century that Stevens made with Gervex.

[5] In Brussels, this section also included The Newly Born (or A Young Woman or Woman in Childbed, after Nov. 1865, private collection), with Mrs. Stevens, visibly exhausted after giving birth, and her newborn daughter, Catherine.

[6] Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, Br. 1990: 553 | CL: 442, Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Antwerp, Monday 28 December 1885. http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let550/letter.html ("Zelfs Stevens voldoet me niet omdat zijn vrouwen niet die zijn waar ik iets persoonlijk van weet.– En ik vind die hij kiest niet de interessantste die er zijn.")

[7] While Gonzalès was also a painter, Stevens did not depict her as such; neither did he paint his friend Sarah Bernhardt in that capacity, even though she painted and sculpted as well. Was this because professional activity by women in those fields still attracted a fair amount of opposition? Yet during the 1880s Stevens taught many women to paint, among them Bernhardt, and the Belgians Georgette Meunier, Berthe Art, and Louise De Hem.

[8] In Amsterdam, the exhibition got an exclusive extra element on Friday evenings, in the form of the project (DE)-Constructing me by designer Catta Donkersloot, in which she showed three films and a tableau vivant. See www.vangoghmuseum.nl/vrijdagavond, www.vrijdagavond.wordpress.com.