The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

| Please note: selected figures are viewable by clicking on the titles of the art works which are hyperlinked. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Art in the Age of Steam, Europe, American and the Railway, 1830-1960 The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri Walker Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool Catalogue: ISBN: 978-0-300-13878-8 Support NCAW: Buy this book at Amazon.com |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

“Oops!” That would be an appropriate caption for the image of the art historian, with hand slapped to forehead, strolling into Art in the Age of Steam, Europe, American and the Railway, 1830-1960 at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. The fact that this exhibition is the first major international exploration of visual artists’ response to the railway seems almost unbelievable. Surely, someone somewhere has already presented this subject. The startling reality is that curators Ian Kennedy (European Painting and Sculpture at The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art) and Julian Treuherz (former Keeper of Art Galleries, National Museums Liverpool) have created the first exhibition and catalogue that present this singularly important aspect of nineteenth and twentieth-century life clearly, coherently, and with art-historical thoroughness. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The crucial role of the railway in the industrial revolution can hardly be overestimated, and there is no shortage of scholarly discussion about the effect of passenger rail travel on Impressionist imagery, for example. With the exception of J. M. W. Turner’s legendary Rain, Steam and Speed, however, there are far fewer analyses of the visual artist’s aesthetic response to the railway. The goal of Art in the Age of Steam was specifically “to show the response of the best artists to the railway, first as a new and revolutionary form of transport, then to the multifarious ways in which the railways transformed everyday life, both physically and psychologically.” (12) This exploration takes the viewer from the earliest decades of purely documentary imagery to the post-World War II era when airplanes began to replace trains as the primary means of long-distance travel. Throughout the exhibition the curators present the theme of the railway in all its complex—and often complicated—forms; as an object of wonder and despair; as a tool of empire building, racism, and glorious industrial innovation; and as a symbolic image that is simultaneously dangerous, boring, and nostalgic. The breadth of this theme is central to the exhibition. It alerts us to both the dominance of the railway in nineteenth and twentieth century images, and to the fact that it has been overlooked as a theme—perhaps because it has become so commonplace that we no longer perceive it as an independent entity. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

It must be noted too that Art in the Age of Steam was the first major exhibition in the new Bloch Building, the165,000 square foot addition to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (figs. 1, 2, & 3). Designed by Steven Holl Architects as five interconnected structures that step down the steep hill to the east of the original museum, the Bloch Building houses temporary exhibition galleries as well as educational rooms and galleries for the permanent collection. These spaces are distinctively lit from a series of clerestories at the top of the above ground sections of the structure; between the doubled glass planking that comprises the wall are ultra-violet light filters and light-diffusing insulation panels. Brilliant natural light floods the space without the damaging effects of unfiltered sunlight. Radiating a luminous glow in any weather condition, the Bloch Building transforms the campus of the Nelson-Atkins museum into a dramatically elegant contemporary space. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The entrance to Art in the Age of Steam takes full advantage of its location halfway down the hillside site (fig. 4). Because sloping corridors link the above ground pavilions, there is a natural sense of moving downhill as you walk towards the special exhibitions galleries that terminate the progression of spaces. Here, the visitor is greeted with an immense orange mural of a locomotive hurtling down a track, echoing the slope of floor, and conveying an immediate awareness of the sheer size of a train engine. It’s an apt way to begin the show. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Turning into the first gallery produces another dramatic shift, this time from the brilliant orange of the entrance to a small grey-walled space filled with early documentary engravings and drawings of railway history.1 These are both informative and charming. S. F. Hughes’ 1833 hand-colored aquatint, Traveling on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, offers a journalistic image British railway engineering as well as the a clear statement about the class divisions of nineteenth-century society (fig. 5). The first class train cars are designed to look like horse-drawn carriages with private, enclosed passenger compartments. The second and third class cars are neither enclosed nor private; third class passengers do not enjoy even the modest safety precaution of fully enclosed sides on the train cars. The aquatint also illustrates clearly that British (and most European) railway tracks followed a straight path, having blasted out hillsides and constructed tunnels if necessary. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This gallery also introduces a basic history of railway development in the form of wall texts. Comparisons between European and American railways are especially informative because the differences will dictate much about future directions and developments. As the exhibition unfolds, these same issues will appear in many of the paintings, posing fresh questions about the relationship between artists and railways. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Here is a summary of the contrasts. European railways tended to be designed along the most direct path between two points, thus facilitating shorter trips, but more difficult and costly civil engineering. In the United States, the track followed the path of least topographical resistance, curving around natural obstacles to avoid expensive engineering fees. In order to accommodate these curves, railway designers developed what is known as a “bogie”, an undercarriage mechanism that balances the wheels on either side of the meandering track. The indirect lines, the poor quality of track, and the resulting slow speed of travel meant that passengers spent more time on the train—and more time distributing their dollars in the hotels and restaurants of the cities along the way. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The scale of the American continent was a formidable challenge, and at least a partial explanation of the differences between European and United States railways. Europeans chose to preserve and protect their natural landscapes by laying rail lines over as little territory as possible. Great feats of engineering design, such as the impressive railway bridges of both Britain and France, testify to a concern for shaping a transportation system that worked within the context of existing communities. In the US, boundless open spaces offered a radically different environment, one in which nature was untamed and wild, often more fearsome than familiar. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

An equally sharp contrast appears in the allocation of funds for railway development. American entrepreneurs hired thousands of laborers, mostly immigrants, to build the railway under dangerous and dismal conditions: low salaries, the daily risk of severe injury; and insalubrious housing conditions. In contrast, European railway owners tended to spend less on manual labor and more on engineers and contractors who could manage sophisticated industrial construction projects. Ultimately, the railway produced diverse results, attempting to support an established way of life in Europe, while in America it played a defining role in expanding the nation. European trains enabled the growth of suburbs; American railways created many of the great cities west of the Appalachian mountains. Not surprisingly, artists responded to these circumstances with a variety of perspectives. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

British artists repeatedly depicted the railway station—a new building type in the nineteenth century, and an opportunity for unfurling epic narratives as hundreds of people gathered in a single place. The possibilities for melodrama were irresistible: the lovers parting or meeting; the young man off to war as his mother waves good-bye; the slimy underbelly of pickpockets and charlatans who prey on naïve passengers; and even the artist himself seeing a friend off on a journey. All of these narratives filled the paintings in the second gallery, appropriately titled “Human Drama” (fig. 6). In particular, William Powell Frith’s The Railway Station, 1862, represents the essence of this type of complex narrative painting. His collection of carefully composed vignettes offers the viewer a snapshot of modern travel: honeymoon journeys about to begin; a fashionable woman trying to smuggle her tiny lapdog onto the train; parents sending their sons off to boarding school; a sailor saying goodbye to his wife and baby; and assorted newsboys, porters, pickpockets and railway station workers. These individual stories collide within the architectural environment of Paddington Station, a vast impressive space that had been photographed by Samuel Fry in 1861 at Frith’s request; the use of these preparatory photographs was noted in Photographic News magazine as part of the advance publicity surrounding the painting (98). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The popularity of The Railway Station was a calculated risk for both Frith and Louis Victor Flatow, the art dealer who commissioned the piece. By the time it was completed in March 1862, Flatow had created considerable promotional buzz about the unveiling of Frith’s latest masterpiece—and his investment paid well. The public streamed into his gallery to see the detailed painting, enjoying the process of discovering the variety of human anecdotes revealed in the complex image. At the close of the exhibition Flatow sold both the painting and the copyright (which Frith had sold to him) to the print dealer Henry Graves, who then produced engravings designed for middle-class patrons eager to hang an affordable reproduction in their homes. The success of this enterprise not only reflects the changing nature of the art market, but also the willingness of the public to accept an industrial scene as a suitable subject for painting. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

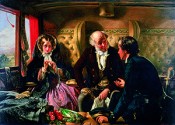

Similarly, the European train compartment supplied fertile ground for sentimental and moral tales. One of the more intriguing is Abraham Solomon’s 1855 painting of a chance encounter in a first class carriage, entitled First Class: The Meeting. . .and at First Meeting Loved (fig. 7). The first version of this work was a forthright image of a young woman modestly receiving the attentions of a well-dressed young man while her father sleeps unaware in the corner of the luxurious carriage. Contemporary critics found this offensive, however, describing the scene as “vulgar” and expressing concern about the careless intermingling of strangers on a train (86). Solomon’s response was to paint a second version, with the woman now directing a practiced sultry gaze at the young man, who seems to have lost interest in anything other than a conversation with her father, newly awake and attentive. The drama has been altered from an unexpected and genuine flirtation to a coy, but publicly acceptable, tale of proper courtship behavior in Victorian England. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Honoré Daumier’s well-known paintings and prints of first, second and third class carriages on French railways were also included in the exhibition. It was particularly rewarding to see all three images side by side, revealing a sequence of human emotions and attitudes that effectively mirror the class structure of the times and the range of responses typical of each group. In First Class Carriage, 1864, the passengers seem both isolated and somewhat fearful; the man on the end of the carriage bench looks warily out to the corridor as if anticipating trouble (fig. 8). The two women are each wrapped up in their private activities, one reading a paper and one staring blankly out the window. The stiff gentleman between the two women seems lost in his own thoughts. In contrast, the1864 watercolor of Second Class Carriage presents a similarly isolated group of four, but now they all react to the chilling temperature of the carriage by bundling up, and huddling into their coats and mufflers (fig. 9). Rather than the abundant physical detail showcased in the British railway compartment imagery, Daumier’s first and second-class carriages present no disparities in terms of furnishings. The class distinction lies in the definition of what is acceptable behavior; first class passengers remain solitary, but engaged in some presumably ‘improving’ activity such as reading or studying the landscape. The second-class group is preoccupied with physical comfort—and they do not hesitate to sleep in public. The self-contained bearing of the family group that is the centerpiece of Third Class Carriage offers yet another attitude toward railway travel. Although grounded in the intense physicality of the nursing mother, this group nonetheless maintains its personal dignity in the face of crowded conditions and the constant chatter of fellow passengers.2 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The “Human Drama” gallery also introduced the phenomenon of the oddly hypnotic effect of the railway compartment. Augustus Egg posits this corollary in his stunning tour-de-force entitled The Traveling Companions, 1862, (fig. 10). Although not a large canvas (25 3/8” x 30 1/8”), it consists of two nearly identical young women who dominate the picture plane and lure the viewer into the somnolent world of train travel. At first glance, these women appear to be twins, wearing the same luxurious gowns with matching hats; closer inspection reveals them to be relatives, but not necessarily twins. While one woman sleeps, the other reads quietly as the passing scene outside the window presents a shining Mediterranean landscape. There is an air of utter quiet broken only by the swinging of the tassel on the window shade to indicate movement of the train. Egg has captured the essence of railway travel—a hypnotic and soothing rhythm that can induce sleep or provide a balm for a weary spirit. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In addition, however, he initiated what would become a tradition of the slightly fantastical aspect of this form of transportation, bewildering the viewer with the curious doubling of the figures and the atypical lack of narrative content. Instead, Egg focused on mood and the sensual pleasure of the exquisitely painted dresses, inviting every observer to fill in whatever story comes to mind—and thus become a part of the open-ended experience of traveling through the countryside in a small enclosed space. The randomness of railway travel, regardless of how carefully planned in advance, can lead to almost anything, as Alfred Hitchcock demonstrated only too well in his 1951 release, Strangers on a Train.3 As with many of the paintings in this exhibition, Hitchcock’s film illustrates precisely the sort of unexpected—and unintended—consequence that might arise from a casual encounter between strangers in a railway car. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Leaving behind the European painting tradition for the fledgling American school on display in the third gallery, the visitor also enters into the first of the spaces illuminated in part by elegant clerestory lighting (fig. 11). Here, the light is “borrowed” from the adjacent space, but it is nevertheless very effective in announcing that the tone of the exhibition is about to change. “Crossing the Continent” picks up the chronological thread established in “Human Drama” and extends it across North America as the railway links the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. American painters respond quite differently than their European counterparts, choosing to focus on both the excitement of the railway as a symbol of progress and on the destruction of the natural world that it caused. George Inness’ 1856 image of the The Lackawanna Valley encapsulates the dilemma (fig. 12). Commissioned by the president of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad, the painting was intended as a promotional piece showcasing the Scranton, Pennsylvania depot and roundhouse—as well as the power of the ever-expanding American railway network. Inness has chosen to present what might have been a straightforward image with a number of jarring elements. First of all, the composition is modeled on the Claudean tradition of seventeenth century landscapes with strategically placed trees on the left side of the canvas to indicate spatial recession, and the small, but brightly colored figure in the middle ground to signify the very temporal role of humanity in the cosmic scheme of things. Into this Arcadian reverie, however, steams the industrial revolution’s signature product, the steam train. It arrives at a fork in the road, much like the classical image of Hercules, but without even the remotest suggestion that there is any moral choice to be made here. Rather, the railway will follow whatever track is designated for that line—and then another train will arrive to trace the alternative track. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Second, Inness refuses to offer an easy answer to the potential problems caused by the railway. He unflinchingly depicted the stumps of trees logged off to feed the steam engines—and positioned them in the foreground of the paining where they cannot be missed—but he makes no comment on this destruction. Naturally, he might have hesitated to do so because this patron was the railway company president, but the fact that he included them at all suggests that perhaps such devastation was understood as the necessary price of progress. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two other paintings from this gallery also speak eloquently to the ambiguous response to American expansion. Both are titled in reference to the western expansion of the continent, echoing the 1861 mural in the US Capitol building by Emmanuel Leutze entitled Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way (129). The paintings, however, are less obvious in their social commentary. Andrew Melrose’s Westward the Star of Empire Takes Its Way—Near Council Bluffs, Iowa, 1867, is a disquieting landscape where the brilliant white headlight of the locomotive screams down the track, and out of the picture plane directly into the viewer’s face. Like the small herd of deer crossing the tracks in front of this oncoming marvel, we are entranced by the shining light appearing out of nowhere, but Melrose also forces us to acknowledge our dependence on the railway as an implement of westward expansion. To the left of the tracks are the modest farms of western Iowa, facilitated in part by the presence of the railway; and by specifying Council Bluffs, Iowa as the location for the scene, Melrose has directed our attention to the engineering accomplishments of the railway bridges across the Missouri River just to the west of this site. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the same gallery is another painting with an equally ambivalent story to tell. Entitled [again] Westward the Star of Empire, Theodore Kaufmann’s painting is also a nocturnal scene with the headlight bearing down upon the viewer, but this time the foreground action consists of Cheyenne men sabotaging the rails of the track. The result of this action was the Plum Creek wreck in August 1867, which in fact was the only actual derailment in the development of the Union Pacific line across the Great Plains (129). Again, it is impossible to interpret this painting in simple terms. Clearly, the impending train accident cannot be condoned. More thorny is the question of whether the sabotage is an act of guerilla warfare in a fight to save the Cheyenne’s rapidly disappearing freedom. Kaufmann offers no answers, but only poses the question. In this sense, American painters are as modern as their European colleagues. Their responses to the railway are equivocal, and as the United States policy of westward expansion continued throughout the nineteenth century, the questions grew increasingly murky. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

For others, such as Albert Bierstadt, the opening of the west was a cause for celebrating the triumph of industrialization (fig. 13). In a typically grandiose landscape painting of 1873, Donner Lake from the Summit, he creates a glorious sunrise above the lake in the High Sierra of California. The fact that the lake—and the pass—were named for the ill-fated Donner Party of 1846-47 only added to the drama of the scene. With the coming of the railway, Bierstadt suggests, the horror of human cannibalism will be forever prevented by the triumphant industrial progress of convenient train travel. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Photographs of American railway development are equally promotional in nature. Most famous is Andrew Joseph Russell’s albumen print of East and West Shaking Hands at Laying of Last Rail (fig. 14). Shot on May 10, 1869 at Promontory Point, Utah, this iconic image documents the linking of the Central Pacific Railroad from California with the Union Pacific Railroad from the east. Russell captured the champagne and beer flowing abundantly as the leaders of the project joined in celebration. Nowhere in this image is there any indication of the men who actually built the lines; Chinese and Irish immigrants whose willingness to routinely risk physical injury made the historic moment possible. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

One of the pleasures of Art in the Age of Steam is the rich intermingling of a wide variety of media, with the expected paintings installed side by side with documentary engravings, casual sketches, engineering-oriented lithographs and etchings, and photographs. The selection of railway photographs is noteworthy not only for their documentary value, but also as yet another exploration of how artists related to the railway; photographers were often hired by railway companies to provide detailed documentation of the growth of the rail networks, and panoramic landscape images that would encourage passengers to visit the American West—via train of course. In fact, these landscape photographs were successfully used to encourage the eventual creation of the U.S. National Parks System at the end of the century (139-141). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

“Artists have to find the poetry in train stations the way their fathers found poetry in forests and rivers.” Written by Emile Zola in 1877, these words announce another shift, this one into the bright light of “Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in the next gallery (fig. 15). The meticulous lighting design of the Bloch Building provides the visitor with the rare delight of seeing Impressionist paintings in natural, albeit UV filtered, light. The clerestory opens the gallery to daylight, washing the paintings with all the effects of light that characterized their original creation. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Of all the time periods covered in this exhibition, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism have probably received more art-historical attention about the influence of the railway than any other. As Zola’s text implied, contemporary painters were fully aware of the need to capture the essence of their own age rather than that of the past, and they eagerly embraced the convenience and adventure of the railway in their personal lives. The myriad paintings of leisure activities along the Seine were possible only because of the accessibility enabled by the railway. What this show sought to investigate was something different: how did the “best artists respond to the railway and the ways in which it transformed everyday life, both physically and psychologically” (12)? The results are mixed for this section of the show, perhaps because the paintings themselves have achieved a kind of “celebrity” status that encourages art historians to view them rather myopically. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Edouard Manet’s The Railway, 1873 is a case in point (fig. 16). Like so much of Manet’s work, it is elusive and therefore open to interpretation. In the context of Art in the Age of Steam, this quality might have been more fully explored, comparing it to the American artists’ ambivalence about the railway and analyzing how these parallel responses were entwined with the specific concerns of divergent cultures and locations. Is George Inness’ reluctance to either endorse or condemn the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad in 1856 a precursor to Manet’s comparable position in 1873? That the painting is always a joy to see goes without saying, but more discussion of its engagement with the railway would have been welcome. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other Impressionist works fare somewhat better, if only because they deal more directly with the image of the railway. One of Claude Monet’s 1877 paintings of Gare Saint-Lazare, a familiar presence in many exhibitions and books, is greatly enriched by being seen in the context of the railway theme. The commonplaces about rapid brushwork and the effect of light on steam are still present, but they are supplemented by a long overdue focus on the subject matter—the railway station as a place rather than exclusively as an excuse to paint moving clouds of colored light. By deepening the analysis of Monet’s subject matter, the curators have included French Impressionists in a discussion about subject matter that is more frequently associated with the discourse on American and British nineteenth century art. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Monet’s paintings related to the railway at Argenteuil bear out the importance of subject matter. The earliest of these is the infrequently seen Gare d'Argenteuil from 1872, which depicts the station as an unapologetically industrial landscape in somber browns and grays. Empty tracks dominate the foreground while the sun rises through a cloudy sky in the distance; just as at the Gare Saint-Lazare in Paris, Monet had to work early in the day when he would not disrupt the railway business. What he chose to paint at the Argenteuil station was not the passenger waiting area, but the switchyard with its lumbering trains and grubby surroundings. Two years later, in Railway Bridge, Argenteuil, he again selected a subject that raises questions about the impact of the railway. This is another iconic image—so over exposed in the marketplace that it is in danger of losing all meaning other than as a promotional lure for consumers. Nonetheless, Art in the Age of Steam gives visitors the opportunity to examine this painting in relation to the railway, and to ask why Monet chose to paint a contemporary, and not particularly attractive, train bridge over the Seine when he could have selected a more appealing view of sailboats, especially if his only intent was to portray the play of light on white surfaces. In short, this exhibition begins an exploration of subject matter in Impressionism that may well deepen our understanding of the art. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Italian painting from the 1870s and 1880s was well represented by Guiseppe De Nittis and Angelo Morbelli. Like their colleagues elsewhere, these artists were fascinated with the railway, with the effects of its passage through the landscape, and its overwhelming presence in modern life. De Nittis’ painting Train Passing, 1878-79, barely indicates the train itself but highlights instead the limitless plume of steam that engulfs the fields in a low-lying cloud. In contrast, two rural women continue harvesting without even acknowledging the locomotive charging through the countryside. The urban counterpart is Morbelli’s Milan Central Station, 1889, a dystopian vision of the overwhelming train shed that seems to have been designed without regard for the scale of human beings. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

On this sobering note, the exhibition moves into the twentieth century with a gallery labeled “States of Mind” where the emphasis is on the more phantasmagoric qualities of the train and its potential for Surrealist manipulation (fig. 17). This is the ideal moment to reflect back on the moody, and eerily similar, women in Egg’s The Traveling Companions from 1862. That sense of unreality that Egg encapsulated will reappear now in even more dramatic form. Paul Delvaux’s The Iron Age from 1951, for example, shows a train heading straight for a modern-day Venus reclining on her bed (fig. 18). René Magritte’s TimeTransfixed, 1938, is also included in this gallery as are many other major paintings from the time (fig. 19). From Wassily Kandinsky to Ludwig Kirchner and from Edward Hopper to Thomas Hart Benton, the paintings in this gallery each deserve thoughtful consideration, as do the works in the following gallery entitled “The Machine Age” which features primarily works on paper, including a variety of posters from the elegant art deco advertising posters for the Nord Express line to Soviet propaganda images of transportation workers. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What connects these seemingly disparate forms are the emphasis on formal stylistic elements and a clearly articulated support for modernism. Art in the Age of Steam concludes with a 1956 photograph by O. Winston Link documenting the collision with yet another stage in the history of transportation: the airplane. Hot-Shot Eastbound, Iaeger, West Virginia shows the future as well as the past as a young couple cuddled in an automobile at the drive-in theatre while the eastbound train steaks along a nearby track. On the movie screen is a scene with an airplane in flight. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Catalogue |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For both the historians and the general public, this is a beautifully produced book, with 210 illustrations in color and 48 in black and white, most of the latter being exquisite photographs. The extensive full-page photo essays alone deserve special mention. In the chapter on “Crossing the Continent”, for example, there are several multi-page spreads of documentary photos of the railway’s western expansion (136-151). Also impressive are the special pages that tackle topics related to the main theme; examples include “The Railway in the American Civil War” “Railways and National Parks” and “Emile Zola’s La Bête humaine”. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Like the railway, this exhibition traverses an expansive territory. At its core is the premise that the railway altered human perception of space and time, with the corollary that a visual artist’s response to these changes would be uniquely focused. As the exhibition unfolded, the contradictions, complexities and confusions inherent in the aesthetic reaction to the steam train emerged. The question of progress in relation to environmental degradation remains with us still, as does the issue of how social classes mix in public spaces. It should come as no surprise then, that artists were often ambivalent about depictions of the railway, even those whose creation of a positive image was in their own best financial interest. Art in the Age of Steam doesn’t shirk from addressing these issues, presenting a remarkably broad range of scholarship interweaving the largely independent fields of industrial technology and art history. Kennedy and Treuherz deserve many rounds of applause for their innovative concept, fresh scholarship, and willingness to think beyond the current narratives of nineteenth-century art. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Janet Whitmore |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1. The use of the word “railway” instead of “railroad” reflects the terminology used in the exhibition and the catalogue. The primary distinction between these words is that “railway” is more common in Britain while “railroad” is favored in the United States. 2. The three watercolor and charcoal versions of Daumier’s railway carriage images appeared only in the Kansas City exhibition. All were loaned by the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. The Liverpool exhibition included the painting of The Third Class Carriage, 1863-65, from the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. 3. Strangers on a Train, directed by Alfred Hitchcock, was released in July 1951 by Warner Brothers. The screenplay by Raymond Chandler and Czenzi Ormonde was based on the novel of the same name by Patricia Highsmith. |