The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

Helene Schjerfbeck: Het geheim van Finland [Finland's best-kept secret] Other venues of the exhibition: Helene Schjerfbeck |

||||||||||

| Although the Finnish Helene Schjerfbeck (1862-1946) is a legend in her own country, she is still virtually unknown abroad. Ninety years after her first solo exhibition at the art dealer's Gösta Stenman in Helsinki, an impressive retrospective exhibition of her work is on display for the first time outside Scandinavia, in The Hague, Hamburg and Paris. (figs. 1, 2). The Independent of London characterised her work as follows: "Imagine the life of Frida Kahlo yoked to the eye of Edvard Munch, and you'll begin to get the measure of this oeuvre…"1 On seeing this wonderful work, one is surprised that Schjerfbeck's name has not become part of the art historical canon. During her life, Schjerfbeck was successful in Finland as well as abroad. Yet the bulk of her oeuvre is still to be found in Scandinavian private and public collections, including the eighty-nine works in the Finnish National Art Museum Ateneum in Helsinki, an important contributor to the exhibition. The exhibition's curator, Dr. Annabelle Görgen from the Hamburger Kunsthalle deserves credit for initiating this long-overdue examination of Schjerfbeck's work. | |||||||||||

| The beautifully and neatly organised exhibition consists of over 120 oil paintings, water colors and drawings, from about forty international public and private collections, some of which are showing their treasures for the first time. In the pretty Gemeentemuseum, designed by architect and near-contemporary H.P. Berlage (1856-1934), the works are shown to their full effect, partly because they are not revealed all at once, as they are housed in eleven sequential, small and dimly lit (and hence intimate) rooms. They prove to be admirably suited to provide a close-up experience of Schjerfbeck's intense oeuvre (fig. 3). The simple and sober rooms have been organised thematically and largely chronologically. As indicated in twelve succinct, bilingual [Dutch and English] notices, the rooms are consecutively dedicated to Helene Schjerfbeck's international recognition, early period of study and travel, self-portraits, nature morte, isolated existence, quest in later life, new public interest, Einar Reuter, works on paper, inspiration, models and reception of Schjerfbeck's work (figs. 4, 5). | |||||||||||

| This arrangement is a good reflection of several aspects of the artist and her work, but it does give a somewhat inconsistent and unbalanced impression at some points in the show at The Hague, probably because of the different spatial arrangement in the organizing museum in Hamburg.2 The room titled "Works on paper", for instance, also contains paintings and archived documents. Likewise, three rooms at the beginning of the exhibition share a single notice ("Early period of study and travel"), whereas one room at the end contains three notices ("A quest in later life", "New public interest" and "Einar Reuter"), creating a somewhat confusing situation. | |||||||||||

| In spite of these details, this is a brilliant exhibition. It starts off with an instructive introductory film (10 minutes, by Bert Koenderink), briefly situating the largely unknown Schjerfbeck and her work in time and space. Additionally, in two darkened side rooms, two longer documentaries from the Finnish Broadcasting Company are shown; at The Hague, a remarkably high number of visitors watch these.3 In the final three galleries, display cases also show photos of Helene and her family, alongside archival documents such as letters, sketchbooks and magazines. | |||||||||||

| It is a happy choice for the exhibition to be shown in Paris after The Hague, as Paris is where Schjerfbeck went at age eighteen, and where she came into contact with the works of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898), Edouard Manet (1832-1883), Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) and Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884), which made her veer from the academic-realistic style in the early 1880s. The influence of Cézanne, for instance, is clearly visible in Shadow on the Wall (Breton landscape) (1883, cat. 12) (fig. 6). Once back in Finland, she kept in touch with the European art scene for the rest of her life, especially through black-and-white reproductions in art magazines and books, which artist friends sent her, as shown in the penultimate room. Schjerfbeck seems to have been aware, for instance, of Vincent van Gogh's (1853-1890) and Pablo Picasso's (1881-1973) work; books on those artists were found among her possessions. Picasso's influence is also evident in a work such as The Skier (English girl) (1909, cat. 46), with an unnatural, clownishly white face, bright red lips, and blushing cheeks against a blue-green background, which also shows Schjerfbeck's awareness of and admiration for Honoré Daumier (1808-1879), who also showed interest in the romantic, tragicomic figure of the sad clown; and because of the strong contours and vivid colours that make some of her portraits approach caricature. Possibly Daumier also inspired Schjerfbeck's paintings Dansing girls (1894, cat. 27) and The alarm (1935, cat. 97), in which the compositional schemes resemble Daumier's oil paintings Children dansing in a circle (c. 1852, Texas, Ritchie Collection) and Family on the barricades (revolution of 1848) (c. 1855, Prague, Národní Gallery) respectively.4 | |||||||||||

|

From Finland to Paris and back The first room introduces the visitor to the artist in the form of a wall-sized photo of Helene Schjerfbeck working in the open air in Ekenäs, Finland, around 1918, when she was already in her fifties (fig. 7). After a teacher discovered Helena Sofia Schjerfbeck's drawing talent, she enrolled in the drawing classes of The Finnish Art Society at the age of eleven. In the room "Works on paper", there are a few early sketchbooks (fig. 8), which might have fit better in "Early years of study and travels", a section which surprises with the consistently high quality of the work of the young artist, such as Museum Visit (1870-80, cat. 4) (fig. 27). In spite of her speedy progress and prizes, as a girl, Helena could not count on much financial or moral support at home to realise her artistic ambitions, even more so because of her father's death in 1876. The financial support of one of her teachers, Adolf von Becker (1831-1909), enabled her to attend classes at his private academy in Helsinki in 1877, where French oil painting techniques were taught. |

||||||||||

| With the aid of a Finnish grant, Helene (the 'Frenchified' version of Helena) travelled to Paris in 1880. She first studied with Léon Bonnat and Jean-Léon Gérôme at Madame Trélat de Vigny's painting studio for ladies, which at that time was visited by many Finnish women artists. In 1881 she went to the private Académie Colarossi, where she was taught by Raphael Colin (1850-1916) and Gustave Courtois (1852-1924), who called her "une de mes meilleures élèves" in a letter of recommendation (included in the exhibition) characterizing her as a consistent and hard worker ("très laborieuse"), and as one of the most talented students ("certainement une des mieux douées").5 Until 1890, she was a frequent visitor to Paris, and in 1884 she had her own studio there, which she longed for again in her final years. With her Finnish 'painter sisters', Marianne Preindelsberger (1855-1927) and Maria Wiik (1853-1928), she headed for Pont-Aven and Concarneau in Brittany in 1881 and 1883-84. Pont-Aven attracted artists from the 1860s onwards, but Schjerfbeck was there earlier than Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), who went to Brittany for the first time in July 1886, making it a colony of plein air painters in the late 1880s and early 1890s. In Brittany Schjerfbeck met an English fellow artist, to whom she became engaged, but the engagement was broken in 1885, and she eliminated any trace of the relationship. Shortly afterwards, she travelled to St. Ives in Cornwall. | |||||||||||

|

In 1883 Helene Schjerfbeck's painting Fête juive was accepted by the Paris Salon, the first time that her work had been displayed at the prestigious annual exhibition. Six years later, at the 1889 World Exposition, where Finland had its own pavilion for the first time, Helene received a bronze medal for her touching painting, The Convalescent (1888, cat. 20), which she had shown the previous year at the Salon as Première verdure (fig. 9). This work shows impressionistic influences, and was undoubtedly inspired by her own fragile health.6 Health problems, and caring for her mother, forced her to return to Finland at that time. As a child, Helene had broken her left hip, preventing her from attending school regularly, and giving her a permanent limp. After 1900, she fell ill more frequently and for increasingly longer periods; in 1917 she wrote: "not a healthy day in 50 years. One gets so tired of fighting".7 Sometimes she was only able to paint for one or two hours a day, and yet she finished almost a thousand paintings in her lifetime. | ||||||||||

| Apart from a few short trips to Italy with her brother, and to St Petersburg and Vienna, Helene Schjerfbeck led quite a modest and secluded life in Finland from the age of twenty-eight, and especially after 1902, when she stopped teaching at the drawing academy and moved to Hyvinkäa, about thirty miles from Helsinki, with her mother. This conscious isolation affected Schjerfbeck's iconography. From that time, she mainly pictured the familiar world immediately surrounding her, and specialised in still lifes, landscapes and (self-)portraits, genres which were considered better suited to women artists than large historical pieces and/or nudes. Also Schjerfbeck's outside landscapes, except for those that originate from her early voyages in France and Italy, are views of surrounding Finnish villages and landscapes (figs. 10, 11). | |||||||||||

| Her portraits are mainly set in interiors, and often represent women and children who were literally, and often also emotionally close to Helene, such as her mother, grandmother or children from the neighbourhood, as can be seen in Primary Schoolgirl II (1908, cat. 42) (fig. 12), Costume Picture (The Baker's Daughter) (1908/09, cat. 43) or The Servant Girl (1911, cat. 53). When no models were available, she would use photographic portraits as a source of inspiration. This was also the case for the portrait of her late father. (cat. 107) The portrait of her nephew Mäns (The Motorist (1933, cat. 91)), on the other hand, was modelled on a Titian portrait that she saw at the Louvre. Partly as a commission by the Finnish Art Society, Helene Schjerfbeck also copied works by the 'great masters' such as Hans Holbein, Frans Hals, Fra Angelico and Diego Velázquez, in the Louvre, the Uffizi in Florence, the Hermitage in St Petersburg, and the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.8 | |||||||||||

| Schjerfbeck mainly portrayed her female models reading, doing needlework, or staring in front of them, always lost in their own thoughts and activities (figs. 13, 14). The atmosphere is both quiet and tense, engaging and distant. Many are shown in profile or three-quarter profile, sometimes even from the back, and often sitting in a rocking chair, like The Artist's Mother (1902, cat. 30), At Home (Mother sewing) (1903, cat. 31), Girl Reading (1904, cat. 32), The Seamstress (1905, cat. 34), Costume Picture (1908/09, cat. 43), Costume Picture II (1909, cat. 44), The Artist's Mother (1909, cat. 47) (fig. 15) and The Artist's Mother (1909, cat. 48) (fig. 14, on right side). | |||||||||||

| In the latter, moving profile portrait, Helene's mother, with her white-grey hair, sits in a white chair dressed in a starkly contrasting long black dress with a scarf; the figure occupies the entire height of the canvas, leaving the rest of the canvas, apart from a wide skirting board, empty and undetermined. It almost seems to be the stylised, somewhat smudged and less decorative mirror image of James Abbott McNeill Whistler's (1834-1903) equally serene portrait of his mother, Arrangement in grey and black, nr. 1. Portrait of the Mother of the Artist (1871, Paris, Musée d'Orsay) (fig. 16). Schjerfbeck knew Whistler's work through reproductions. In a display case in the penultimate room, The Studio is left open at an article about him, with a reproduction of a seated, reading woman who, as in Schjerfbeck's painting, only just fits in the frame.9 | |||||||||||

| Clearly it was not Schjerfbeck's priority to portray her models true to life; their presence, strong personalities, and their plastic rendition were much more important. This can also be seen in the fact that Helene Schjerfbeck, from 1927 onwards, used her own previous paintings as models for newer, often freer paintings, drawings and lithographs, (e.g. The Seamstress, 1905, cat. 37; and The Seamstress, 1927, cat. 83). These 'reincarnations' are in fact 'repeats' of earlier motifs in a new formal language, often based on small black-and-white reproductions of her own work. | |||||||||||

| Self-portraits and still lifes as echoes of one another Even though the serene images of close friends count among the most powerful of Schjerfbeck's oeuvre, the limited involvement of her oeuvre with the world might also show a certain lack. In spite of living through both World Wars – at the outbreak of the Finnish-Russian Winter War in 1939 the artist was evacuated and five years later she moved to Sweden – the outside world is almost completely missing in her oeuvre. The origin of the gloom and existential crisis emanating from her (late) self-portraits is probably to be found in the first place in Schjerfbeck's lonely searching and somewhat melancholy personality. She later wrote about this herself: "At home they were serious and grim, and I took everything seriously, too – just the way I still do."10 Her self-portraits are a perfect reflection of her "dark, poor inner self".11 As a matter of fact, both eyes are often worked out differently, which might point to Helene's double vision – oriented inwards and outwards – according to Uwe M. Schneede, former director of the Hamburger Kunsthalle, who dedicated a separate article in the catalogue to the theme: " 'Zo legt de schilder zijn ziel bloot'. De zelfportretten" ['So the painter bares his soul.' The self-portraits]. |

|||||||||||

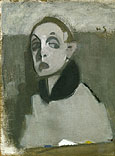

| The organisers made Schjerfbeck's self-portraits the heart of the exhibition, which is also evident from the choice of a 1912 self-portrait (cat. 56) for the poster and catalogue cover (fig. 17).12 In a separate room, more or less in the middle of the exhibition, over half of her nearly forty self-portraits are displayed – the first made around 1884/85 (cat. 18) and the last immediately before her death (cat. 123) (figs. 18, 19, 20). It is remarkable, though, (and the reason is not clear to me) that the organisers did not hang the portraits in this room entirely in chronological order. | |||||||||||

| The self-portraits make for a harrowing and outspoken psychological portrait of the aging artist, who records with unreserved frankness and keen self-observation, not only her physical change and eventual deterioration, but also her soul, her doubts, mental torments, and fear of death (fig. 21). It does not seem unthinkable that, with the rise of psychoanalysis around the turn of the century, those new interests in the innermost stirrings also had an influence on the self-portrait genre. Women artists especially devoted themselves to self-portraiture, for example, Thérèse Schwartze (1851-1918), Suzanne Valadon (1865-1938), Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907), Marie Laurencin (1883-1956), Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) or Charley Toorop (1891-1955), whose Self-Portrait with Palette can be seen in the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague.13 | |||||||||||

| Schjerfbeck's self-portraits, showing at most part of her upper body, get their strength from the facial expression and the look. They hardly ever contain references to her physical condition or handicap (in contrast with e.g. Frida Kahlo), her surroundings, or her being an artist. An exception to the latter aspect is the self-portrait commissioned in 1914 by the Finnish Art Society for their conference room – she was the only woman among the nine artists they contacted (cat. 59) (fig. 22). She wrote about it as having "a black background and against that background a silver inscription like on a headstone".14 | |||||||||||

| Regardless of the pride and self-consciousness emanating from this portrait, the artist, who was then fifty-three, was concerned with the temporariness of fame and the finiteness and vanity of life, a theme she had also touched upon in an early vanitas scene (Still Life, ca. 1877, cat. 2). Beginning with the self-portraits from the late 1930s until her death in 1946 Helene seems to have been wrestling with that in particular. In the last self-portraits, she only appears a shadow of herself, almost a ghost in which her skull can be noticed, with large, deep eye sockets set off by only a few heavy, dark brushstrokes (fig. 23). This striking cycle is reminiscent of Leon Spilliaert's (1881-1946) countless gloomy self-portraits (both artists were insomniacs), Edvard Munch's, or Käthe Kollwitz's (1867-1945) equally sharp observation of her slowly deteriorating body and face. | |||||||||||

| It was a good choice by the organizers, both as far as content and form are concerned, to install a display room for Helene's still lifes in the middle of the self-portrait room in the Gemeentemuseum (fig. 24). The designers see, in both genres, "quiet monologues of the artist", and in the still lifes "an echo of the personal process of aging".15 In both genres, Helene Schjerfbeck records and considers development and decay (e.g. Still Life with Blackening Apples; 1944, cat. 114), and she is absolutely free to experiment with paint, as neither in the self-portrait nor in the still life do the feelings of the model have to be taken into account. | |||||||||||

| Schjerfbeck's evolution towards simplification and abstraction, and her search for emptiness and stillness can clearly be noticed in the way she produces both genres, constants in her oeuvre. If her Still Life dated 1879 (cat. 3) or her Onions, dated 1883/84 (cat. 14) are not presented in the smoothest, slickest manner, the style later evolves, from Still Life (ca. 1907, cat. 41) and The Red Apples (ca. 1915, cat. 60), to The Apple at Market (1927, cat. 87), The Pear (1925/26, cat. 79) or Pumpkins (ca. 1937, cat. 98), more and more in the direction of quasi-abstract areas of color only vaguely hinting at the contours of fruit and vegetables (fig. 25). In 1914, when Gösta Stenman showed her Juan Gris' (1887-1927) Cubist Composition, she was very much impressed by this "still life in blue, violet and pink".16 | |||||||||||

| A personal, innovative style Helene Schjerfbeck closely followed the European artistic developments, but she simultaneously developed her own characteristic formal language, which was not only representative of her time, but occasionally seemed to be ahead of it. Very soon indeed Scherfbeck's painting evolved from a melancholically tinged late nineteenth-century academic realism, with naturalistic and impressionistic influences, to a very personal style, which carries the roots of expressionism—and from a very early stage tended toward abstraction. She attained an expressive imagery through the reduction of the narrative and her color palette, by leaving out more and more detail, and working with fields and two dimensions, without abandoning depth. Schjerfbeck herself wrote: "A work of art always lacks the last few details; the finished is dead."17 In literature, she also saw confirmation of the principle that "we do not [need to] list every detail; a hint brings us closer to the truth."18 So she went in search of the essence and the power of emptiness through the simplification and blurring of pictorial elements, and the omission of the unnecessary. Helene Schjerfbeck tried to express as much as possible with as little as possible. |

|||||||||||

| Some paintings have a particularly contemporary feel to them because of this stylised line and blurred form. A wonderful example is The Door (cat. 16) painted in 1884 in Pont-Aven, which stands out because of the large areas of color, the unfinished character with its rough, wide brush strokes, the impasto, and the occasionally bare spots of canvas (fig. 26). The unusual point of view, convergence lines leading nowhere, rather unrealistic use of colors, the near absence of figuration, and the subtle suggestion of light kept out all evoke emptiness and stillness. Although realism and naturalism, with their faithful rendition of detail, were still authoritative in France and the rest of Europe, this work shows a strongly pictorial, almost abstract principle. | |||||||||||

| A similar analysis can be made for canvases such as Museum Visit (1870-80, cat. 4) (fig. 27), Park Alley (1882-84, cat. 11) (fig. 28), Park Bench (1883, cat. 10), The Pear Tree (1905, cat. 35), Church Window (1919, cat. 68 and 69), The Old Brewery (1920, cat. 75) or Lantern Light, Hyvinkää (1925, cat. 78). Without titles, the specific subjects of these still figurative works would be difficult to discover, which is surprising especially in the case of the earliest examples, keeping in mind the 1888 date of Paul Sérusier's The Talisman (Bois d'amour near Pont-Aven). The painting and the technique demand attention and appear to have been Schjerfbeck's goal. Expression rather than representation seemed to fascinate her. Painting as an art refers to itself here; the space is almost reduced to paint as a substance on a field. | |||||||||||

| Similarly, Drying Laundry (1883, cat. 13) gives rise to a suspicion that the painter chose this theme for the possibility of picturing large, undetermined areas of color from an unusual perspective rather than for any documentary reasons (fig. 29). Because of the somewhat strange vagueness and framing of the canvas, and the fuzzy spatial setting, the painting understandably bewildered some contemporaries: "Miss Schjerfbeck's second work is an original, extremely original painting. It shows laundry being bleached. [...] One is, at first, almost frightened by such an image, in which not a single tree or bush is introduced to indicate a 'landscape', and where nothing is done to give the whole thing the impression of a 'depiction'...".19 When the painting was entered late and without a title for the annual exhibition of the Art Society in Helsinki in 1883, it was hard to find a title to match; it was called Dune Landscape. | |||||||||||

| Her portraits also offer surprising new developments, such as the richly varied but fairly rough and undefined background suggesting depth in the monumental images of Helene's grandmother: Grandmother (Sofia Printz) (1882, cat. 9), to which Ernst Josephson's later Portrait of Ludvig Josephson (1883) shows a certain similarity, and Old Woman (grandmother) (1907, cat. 40). Another example is the rough, wide brush strokes woven in a rich palette of colors, and positioned next to a woman's head in Profile of a Woman, dating from 1884 (cat. 15). | |||||||||||

| Schjerfbeck also found inspiration for this tendency to austerity, stillness and abstraction in Japanese prints in fashion since the 1870s, especially in Paris (e.g. Katsushika Hokusai and Ando Hiroshige). After 1900 she studied the technique and aesthetics of Japanese woodcuts, which can be seen in her monochromatic, jade-colored Costume Picture (the baker's daughter) (1909, cat. 45), in Girl in a Rocking Chair (1910, cat. 51 and 52), Heat Wave (1919, cat. 71), or in Paavo (1912, cat. 57) (fig. 30), with their sparse rending of detail, and their sober lines and choice of color. Under the influence of Art Nouveau, and possibly also Japanese art (she called her first design Japon), Schjerfbeck also designed stylized patterns for tapestries and cushions, but those are not represented in the exhibition. | |||||||||||

| Even though the design of needlework patterns was probably a contributing factor in Schjerfbeck's simplification and stylization of forms, the absence of such designs and artefacts, which are often associated with conservative and inferior – women's – handicrafts, may be linked with the aspiration of the exhibition designers, be it consciously or unconsciously, to show the innovation, originality and modernism of the artist's painting, and as such its relevance in the art historical canon. Annabelle Görgen's article "Helene Schjerfbeck – a telling silence" seems to point in this direction. Exactly because female artists are more often seen as followers than as innovators, such an interpretation offers a surprising and refreshing view, which is hardly an inappropriate exaggeration, but is convincingly substantiated by in-depth analyses. Such a view, or rather such an aspiration, does not question the truism that innovative art is superior, though, which has had detrimental consequences for the assessment and reception of many a female artist (who were innovative by their choice for an artistic career in the first place). | |||||||||||

| Contemporary and recent reception The fact that Helene Schjerfbeck soon enjoyed a considerable reputation in Scandinavia was largely due to the lumberjack, writer and artist Einar Reuter (1881-1968), and the Swedish journalist and art dealer Gösta Stenman. In 1914 Reuter bought one of Schjerfbeck's paintings, and one year later he visited her in Hyvinkää. They became life-long friends, and discussed international developments in the arts, art books and magazines. Under the pseudonym H. Ahtela, Reuter wrote the first biography of the artist in 1917, on the occasion of her first solo exhibition in Helsinki, organised by Stenman. And so, public interest in her works was revived, first in Sweden and Finland, and in the ensuing decades a few of the works were selected for international group exhibitions, among others in Stockholm, Paris, Berlin, Düsseldorf, Hamburg, Milan and Rome. In 1956 Helene Schjerfbeck represented Finland at the 28th Venice Biennale and thirteen years later, in 1969, the first, small and until now the only European solo exhibition of Schjerfbeck's work outside Scandinavia was held in Lübeck. |

|||||||||||

| In the United States, Helene Schjerfbeck had some success between 1949 and 1953 as a result of a small solo exhibition, organised by Stenman's wife, which toured no fewer than forty cities; in 1992, a new exhibition took place in Washington and New York, organised by the Helsinki Ateneum. Apart from the long sold-out catalogue of the former exhibition, the catalogue of the latter is the first comprehensive monograph about the artist to be published outside Scandinavia. In the last gallery, "Reception of Schjerfbeck's work", two display cases show contemporary books and articles devoted to Helene Schjerfbeck or mentioning her (e.g. "Some Finnish women painters") (fig. 31, 32). At the end of this room, which also functions as a reading room for visitors, there are a few copies of the new exhibition catalogue, which contains a separate article on the reception of Schjerfbeck, under the telling title: " 'Ooit zal men het werk van deze Finse kunstenares tot het Europese cultuurgoed rekenen'. De receptie". ['One day the work of this Finnish artist will be counted among the heritage of Europe'. The reception]. | |||||||||||

| After a preface written by the directors of the three institutions involved, the catalogue contains four well-researched, scholarly articles focusing on four separate themes, which precludes too much overlap. First the German Annabelle Görgen tackles the idiosyncratic element in the work of Helene Schjerfbeck. In a second article, entitled " 'In feite is het juist het leven van de mens dat mij fascineert'. Het leven en werk" ['In fact it's human life that fascinates me'. The life and work], Leena Ahtola-Moorhouse, chief curator of the Helsinki Ateneum, offers a concise and chronological overview of Schjerfbeck's life, work and sources of inspiration, based on the current, fairly comprehensive knowledge about this. As mentioned earlier, these are followed by a discussion of the self-portraits, by Uwe M. Schneede, and the reception of Schjerfbeck, again by Annabelle Görgen. | |||||||||||

| Görgen points out that Helene Schjerfbeck's work was initially interpreted through her 'tragic-romantic' life, from beginning as a prodigy but evolving into ailing, limping woman, rejected lover and self-sacrificing daughter, and finally to an etherealised outsider. This subjective interpretation, stressing Schjerfbeck's role as a victim, was on the one hand inspired by Reuter's 1917 biography and 1951 monograph about the artist, and on the other hand by Schjerfbeck's own writings; over 2000 letters were preserved. Both contributed to the myth that was created around her person in Scandinavia. Görgen appropriately points out that this biographical vision tends to bias our understanding of Schjerfbeck's work too much, and that more historical distance should allow the oeuvre to speak for itself. | |||||||||||

| The bulk of the book consists of exquisite large color illustrations of the exhibited works of art, which is very valuable, all the more because many of the works come from private collections, and reproductions are consequently hard to come by. The chronologically ordered color illustrations are followed by a list of exhibited works with their provenance and all the technical data. The chronological biography at the back is also enlightening and useful; it situates Helene Schjerfbeck's life in relation to the evolutions of the plastic arts inside and outside of Scandinavia, and the general political and social events in Finland and the rest of the world. Positioning Schjerfbeck in her time highlights the innovative character of her work – especially during the 1880s and '90s. | |||||||||||

| The fact that the exhibition visits three reputable European museums, and the translation of the catalogue in several languages, is critically important for the further fame and reception of this oeuvre. The high numbers of enthusiastic visitors in Hamburg and The Hague, and the fact that all exhibition catalogues were sold out even before the end of the exhibition, are telling indications of the present day appreciation of this work, and good omens for the future interest in Helene Schjerfbeck. | |||||||||||

| Marjan Sterckx, Ph.D. School of Visual Arts, Hasselt & Media- and Designacademy, Genk, Belgium sterckx.marjan[at]gmail.com |

|||||||||||

|

1. Boyd Tonkin, in The (London) Independent (31 Oct. 2003), on the publication of Rakel Liehu's novel Helene (Helsinki, 2003), based on Helene Schjerfbeck's life. 2. It remains to be seen to which extent the arrangement can be convincingly maintained in the larger and higher spaces of the Musée d'art moderne de la Ville de Paris. 3. The longest (57 minutes) of the two documentaries can also be seen in a separate room outside the exhibition proper, close to the entrance of the Gemeentemuseum, possibly in order to meet the demand of the many interested, who sometimes can't all get into the small projection rooms in the exhibition. 4. Comparison suggested by Leena Ahtola-Moorhouse in her article in the exhibition catalogue Schjerfbeck, 2007, 24, 29. 5. Letter of recommendation by Gustave Courtois to unknown addressee, Paris, 29 March 1881; translated from Schjerfbeck, 2007, 167, cat. 130. 6. The painting was first exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1888, and was bought by the Art Society. It cannot be ruled out that Helene Schjerfbeck was also inspired for the theme by The Sick Child (1885/86) by her Norwegian contemporary Edvard Munch (1863-1944). 7. Helene Schjerfbeck to Einar Reuter, 22 February 1917; translated from Schjerfbeck, 2007, 193. 8. In her Girls Reading (1907, cat. 36) Helene Schjerfbeck painted a stylised reproduction of Hans Holbein's portrait of the well-read Erasmus of Rotterdam (1523, Paris, Louvre) on the wall behind the two girls. 9. The Studio, XXIX, 126 (September 1903). It might have been interesting to show both images in the same room. 10. Gotthard Johansson, Helene Schjerfbecks konst (Stockholm, 1940) 15; translated from Schjerfbeck, 2007, 171. 11. Helene Schjerfbeck to Einar Reuter, 14 April 1920; translated from Schjerfbeck, 2007, 35. 12. More or less simultaneously with the exhibition in The Hague, the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent showed the exhibition "Artists' Portraits", containing many self-portraits of (male) Belgian artists. 13. Cf. Frances Borzello, Kijken naar onszelf. Zelfportretten van vrouwen [Seeing Ourselves] (Alphen aan den Rijn: Atrium, 1998); Liz Rideal, Whitney Chadwick and Frances Borzello, Mirror Mirror: Self-Portraits by Women Artists (Watson-Guptill, 2002). In 1914 Gösta Stenman showed Helene Schjerfbeck drawings by Marie Laurencin. 14. Helene Schjerfbeck to Einar Reuter, 27 Aug. 1915; translated from Borzello, Kijken naar onszelf [Seeing Ourselves], 125; Schjerfbeck, 2007, 35. 15. Annabelle Görgen, " '…and I'm afraid I long for great, profound and fantastic things.' Helene Schjerfbeck – a significant silence" in Helene Schjerfbeck, 2007, 10. 16. Helene Schjerfbeck to Maria Wiik, 25 July 1914; translated from Schjerfbeck, 2007, 191. 17. Letter by Helene Schjerfbeck to Dora Estlander, 1928; translated from Schjerfbeck, 2007, 9. 18. Helene Schjerfbeck to Einar Reuter, 16 April 1917; translated from Schjerfbeck, 2007, 11. 19. Helsingfors Dagblad, 23 November 1883; translated from Schjerfbeck, 2007, 177. |

|||||||||||