The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|

Constructing the Canon: The Album Polish Art and the Writing of Modernist Art History of Polish 19th-Century Painting |

|||||

|

In November 1903, the first issue of a new serial album, entitled Polish Art (Sztuka Polska), appeared in the bookstores of major cities of the partitioned Poland. Printed in a relatively small edition of seven thousand copies by the firm of W.L. Anczyc & Co., one of the oldest and most respected Polish language publishers, and distributed to all three partitions by the bookstores of H. Altenberg in Lvov (the album's publisher) and E. Wende & Co. in Warsaw, the album was a ground-breaking achievement. It was edited by Feliks Jasieński and Adam Łada Cybulski, two art critics with well-established reputations as supporters and promoters of modern art. However, what distinguished Polish Art from earlier publications was not its authorship, since Polish critics often published books dealing with native art, but rather its novel format and ambition. The album was the first Polish—and one of the first European—art publications to rely on full-color photomechanical reproductions, rather than descriptions of artworks. It included sixty-two color and three black-and-white plates, which illustrated sixty-one works by twenty-five Polish painters. Each plate was accompanied by a short essay written by one of twenty contributors, who included, in addition to the two editors, eminent Polish journalists, writers, artists, and art historians. Even more striking than its use of illustrations, was the album's content. Polish Art was the first Polish language art publication intended for the general public that embraced the conventions of canonical art history in order to identify the greatest Polish painters of the nineteenth century. In a striking example of historic agency, it set in place the canon that to this day informs public perception and scholarship on the period. | |||||

| The album's didactic tone and nationalistic message, its focus on visual, rather than verbal presentation, and use of expensive folio format and high-quality paper; in short, qualities that identify it as an early example of the ubiquitous "coffee table" art book, were calculated to appeal to a particular audience. They were aimed at educated, patriotic, middle class readers, whose disposable income could accommodate the album's subscription price of thirty Austrian crowns, and whose social identity required at least a cursory familiarity with national culture. The acceptance or rejection by this group of the album's two implicit claims: the identification of modern art with quality and the definition of national artistic tradition as a gradual evolution towards modernism, had serious consequences. The album's intended readers were also the primary consumers of contemporary art. They constituted the public that attended shows, read reviews, purchased catalogues, formed the membership of the local art societies, sponsored public art projects, accorded recognition and status to artists in their mists, and, of course bought, original works. | ||||||

| The editors' awareness that the album's target audience constituted the primary support base for contemporary art informed every aspect of the project, from the album's content to its physical appearance. Although the work's full title, Polish Art. Painting. 65 Reproductions of Works by the Foremost Masters of Polish Painting suggested a historic survey of the greatest Polish painters, the album's "gallery of national masters" was far from comprehensive or inclusive. It included no artists born before 1800. Furthermore, while it spanned the nineteenth century, it clearly focused on the century's last quarter, the period associated with the emergence in Poland of self-consciously modern art, christened by the critics in the mid 1890s as modernizm, after the German Modernismus. Of the twenty-five artists featured in Polish Art as "the foremost masters of Polish painting," fifteen (sixty percent of the total) were still alive in 1903 and all, without exception, would have been identified by contemporary critics as modernists (moderniści). All fifteen were members of the artist-run exhibition society, the Association of Polish Artists "Sztuka" (Towarzystwo Artystów Polskich "Sztuka"), founded in 1897 by a group of progressive Krakow painters to promote modern Polish art, namely, their own work, at home and abroad. Seven were the society's founders.1 Among the fifteen were also six current and three future professors, as well as a current director of the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts, which, after its 1895 reorganization, functioned as the institutional base for Polish modernizm and played a key role in transforming modern art into fully mainstream, academic practice.2 | ||||||

| The album's emphasis on the last quarter of the nineteenth century was in marked contrast to how the national painting tradition was previously characterized. Although not much had been written on the subject prior to 1903, there was a major exhibition organized in Lvov in 1894, which aimed to survey the history of Polish painting. In 1897, a companion volume to the show entitled One Hundred Years of Painting in Poland, 1760-1860 was published by Jerzy Mycielski. Mycielski's book provided a highly detailed account of the careers of Polish painters active from the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. It was broadly inclusive and encyclopedic in character, giving no emphasis to any stylistic tendency or particular period within the hundred-year span covered by the show. It mentioned ninety-eight Polish painters, fifty of whom were active in the second half of the nineteenth century.3 Of that group, Polish Art recognized a total of six. | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Despite the blatant omission of key figures—painters such as Henryk Siemieradzki, Józef Simmler, or Józef Brandt, who were recognized as significant national artists, but whose work was fundamentally at odds with modernist values—Polish Art did not meet with a hostile reception. It was received enthusiastically by the Polish press and hailed as a monumental achievement. The notices announcing its publication and reviews that followed were without exception highly complimentary. No one seemed to have noticed the publication's highly partisan nature. And, interestingly, no one since then has seriously challenged its judgments. The fact that a hundred years later, the canon of nineteenth-century Polish painters set up by Polish Art still looms large—informing public perception and curatorial practice, as well as scholarship on the period—raises several questions. Why was it so readily accepted, despite clearly evident bias, and why did it prove so enduring? What conditions were present in 1904 that allowed such an uncritical and overwhelmingly positive response? What, if any, strategies did the editors use to ensure this outcome? Was, for instance, their choice of format—reliance on color reproductions, in particular—significant in this respect? More broadly, what can we learn from this specific publication about the process and conditions under which the canon of nineteenth-century European art emerged in the first decades of the twentieth century? And what does it suggest about the relationship of canonical art history not only to particular ideologies, in this case modernism, but also to specific conditions of the art market? | ||||||

|

The modernist bias of Polish Art is not surprising when one considers the identity of the album's two editors. Feliks Jasieński and Adam Łada Cybulski, were members of the closely-knit Krakow art community. Prior to undertaking work on Polish Art, both wrote criticism for a broad range of Polish-language periodicals and newspapers, gaining reputations by 1903 as vocal supporters of modernism.4 Jasieński, in particular, was an important figure in the early history of the movement (fig. 1). A son of a prosperous landowner, he was not just a sympathetic critic, but also a passionate collector, popularizer, and promoter of modern art. Jasieński spent much of his youth abroad traveling throughout Europe. He eventually settled in Paris, where he developed an interest in contemporary art and became well acquainted with artistic and literary modernism. It was there that he began collecting contemporary and Japanese art, focusing in particular on acquiring prints. On his return to Warsaw in 1889, he immediately began using his growing art collection to establish and maintain a public presence. He organized temporary exhibitions of prints from his holdings, gave public lectures on modern art, and eventually began publishing his views. He also became a member of the Warsaw Society for Encouragement of Fine Arts, a local art society, which operated the city's main exhibition venue. There he played an important role as an early supporter of Polish impressionism and an advocate of artists whose work challenged traditional stylistic and thematic norms. In 1895, he was instrumental in organizing a posthumous retrospective for Władysław Podkowiński, an artist who gained notoriety in the mid-1890s for his daring impressionist and symbolist works, and who was Jasieński's close friend. It is important to note that Polish Art reproduced two paintings by Podkowiński, including his most notorious symbolist work, The Ecstasy (1894) (fig. 2), which Jasieński owned. | |||||

| When Jasieński moved to Krakow in 1901, he quickly became one of the most active and vocal members of the city's social and cultural elite. Krakow had become by then an undisputed center of Young Poland (Młoda Polska), a movement which embraced varied manifestations of literary and artistic modernism. Jasieński immersed himself in the city's art community, transforming his home into Krakow's premier cultural salon. Well-acquainted by then with the painters who four years earlier formed Sztuka, he became actively involved in the society's activities, serving as an unofficial, "behind the scenes" consultant and backer. He also continued the practice he began in Warsaw of organizing shows of works from his personal collection. In January 1902, he created two such exhibitions: one at the National Museum consisting of six hundred Japanese woodcuts, and another at the Palace of Art, the home of the Krakow Society of Friends of Fine Arts (a counterpart of the Warsaw Society for Encouragement of Fine Arts), consisting of works by contemporary Polish artists, most of whom were featured less than two years later in Polish Art. | ||||||

| That same year, Jasieński also became involved in a project that bore striking affinity to his work on the album. He was instrumental in founding the Association of Polish Graphic Artists, an organization dedicated to promoting Polish contemporary art through production of high-quality, but relatively inexpensive original print portfolios. The association's first portfolio, which appeared in 1903, just a few months before the first issue of Polish Art was released, was issued in a limited edition of 120 and, like the album, was sold by subscription. It quickly sold out, largely as the result of a successful marketing campaign spearheaded by Jasieński, which involved exhibition of the portfolio prints at the National Museum, their pre-publication subscription sale, distribution abroad, and extensive local press coverage.5 No doubt, this outcome confirmed for Jasieński, as well as the financial backers of Polish Art—all of whom were concerned with the project's commercial viability—the potential for success of their planned venture. | ||||||

| The album's other editor, Adam Łada Cybulski, also had close personal ties with the Krakow modernists. Born in 1878, he was by more than a decade Jasieński's junior. Although he had considerably less stature than his colleague and was clearly his subordinate on the project, Cybulski was equally well acquainted, though perhaps on different terms, with the artists who formed the core of Polish Art.6 His relationship with the Krakow artists began during his association with a short-lived, though extremely influential, modernist periodical Life (Źycie). Edited by Stanisław Przybyszewki, Life promoted literary and artistic modernism and counted among its contributors key members of the Krakow modernist circle. Stanisław Wyspiański, a founding member of Sztuka, a professor at the Krakow Art Academy since 1902, and one of the artists prominently featured in Polish Art, was the paper's artistic director. Between 1897 and 1898 Cybulski wrote a number of articles for the journal and served as one of its French translators. After the journal folded, he continued writing criticism for a variety of newspapers and from 1902 to 1904 published a regular column in the journal The Week (Tydzień). In 1906, a year after Polish Art completed its run, Cybulski was hired by Julian Fałat, the director of the Krakow Art Academy, as the school's administrative assistant (sekretarz). The same year he also began to be identified in Sztuka's exhibition catalogues as the society's "recording secretary." In 1908, Cybulski was appointed as a docent of art history at the academy, a position he held until 1911. | ||||||

| It is obvious that Jasieński and Cybulski were not just sympathetic critics supporting modern art. They were true insiders. In promoting modernism on the pages of Polish Art, they were promoting work that they themselves were deeply professionally and personally invested in. Given the closeness of their relationship with the artists, one could go a step further and argue that they did not just promote modernism, but in fact acted on behalf of the artists and, ultimately, represented their interests. I would like to suggest that they should be viewed, therefore, as spokesmen acting on behalf of a well-organized and cohesive group, rather than as independent agents. If one accepts this premise, then one must conclude that the fifteen living artists included in the album, in effect, wrote themselves into art history. By strategically manipulating its conventions, they constructed a canon of nineteenth-century Polish art in which they themselves were prominently featured and in the process set up a paradigm of aesthetic and historic significance that not only informed subsequent assessments of the period, but also of Polish twentieth- century art. | ||||||

| The program of Polish Art reflected Jasieński's and Cybulski's views and their experience as art critics. The album did not present a historic narrative of national art. Instead, it functioned as a portable art museum, which, ironically, given the album's focus on images, identified the canon of great masters of Polish painting, rather than of masterpieces. Each of the fifteen issues of the album contained between four and five color plates. Inside, pages alternated between matte gray and semi-glossy white paper. The gray pages contained and framed large color reproductions printed on semi-glossy paper, typically 7 ½" x 9 ½" in size (figs. 1, 2, 5, 8). The photographs were cropped to the edge, establishing an implicit correspondence between the reproduction and the original. Glued in, rather than printed on the page, and accompanied by no labeling text, the reproductions "hung" on the surface of the matte, gray paper, evoking paintings hanging on gray walls. The familiar consequence of photomechanical reproduction evoked by Walter Benjamin in his essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Photomechanical Reproduction" did not apply here. The striking novelty of the color photographs, in conjunction with the presentation which enhanced the perception of the image's precious quality, not only did not destroy the aura of the original, but conferred an auratic presence on the photographs, allowing the album to function as a simulacrum of an art collection. | ||||||

|

In effect, the photographs were presented not as illustrations, but as substitutes for the absent originals. The second edition of the album, which appeared in 1908, made this point explicitly. "Polish Art is our only publication which gives an exact impression not only of the form, but also of the color of the reproduced paintings," announced a note from the publisher appearing in each issue.

|

||||||

| The magic of color photography was supposed to engender desire for a visual as well as actual possession. A note from the publisher, which appeared in the first three issues of the first edition of the album, explicitly stated that the editors' primary goal was to "hand over the ownership" ("uczynić własnością") of works of national art locked up in museums and private collections to the Polish public. Interestingly, the secondary goal of the album, identified in the same note, did not imply such a transfer of possession. It simply expressed the editors' desire to give access to Polish art to Europe, and the world.8 This contrast between the two stated goals established a fundamental difference between access and ownership, the knowledge about and the possession of a work of art. To have access meant to take into consideration, to recognize as important; to possess meant to accept without qualifications, to respect, to take pride in, and to cherish as a reflection of one's own identity. | ||||||

|

The white pages, which preceded the reproductions and framed the image discursively, provided reasons for why the reader should respond this way. Each page included the artist's portrait in the upper left corner, information regarding the reproduced work (artist's name, dates, title, and, significantly, the name of work's current owner), and a short essay (Fig. 3). Without exception, the essays focused not on the reproduced works, but on the artists. They informed the reader about the significance of the artist's entire oeuvre, rather than the aesthetic merit of the reproduced work. If they mentioned the reproduced work, they did so in the most cursory manner in a sentence or two. Most often, they failed to mention the work all together. The attention given to the artist rather than the work, the master, rather than the masterpiece, implied that any piece by the artist's hand could be substituted without negating the validity of the text's claims. While this approach identified the artist as the ultimate source of the work's value, it also liberated the work from textual dependence. Freed from illustrative function, the images could operate as surrogate works of art and the album as a virtual national "museum without walls." | |||||

| The focus on the artists also had another effect. It identified the entire oeuvre of the featured artists as national patrimony. If accepted, such designation would have had significant and immediate consequences for the painters, as well as collectors. It would have conferred special status on any work produced, making value dependent on the presence or absence of a signature, rather than particular formal characteristics, an ironic situation given the modernist insistence on the autonomy of a work of art. Although this logic bears a superficial resemblance to the shift from canvases to careers within the late nineteenth-century French art world identified by Harrison and Cynthia White, it is ultimately based on a different premise.9 Whereas in the French market-driven system the shift was predicated on demand-supply factors, internal competition, and the time-honored rhetoric of genius, in Poland it was motivated by political considerations; in particular, the special value accorded national culture. For Poles, whose country did not exist, having been erased from the map of Europe through the partition by Russia, Prussia and Austria, national culture signified more than an expression of the nation's spirit, to use the nineteenth-century language. It provided a tangible evidence of the country's continual survival under occupation. As a consequence, artists, writers and musicians were frequently treated as national heroes whose works attested to the nation's endurance and vitality, and, ultimately offered compelling proof of the injustice of Poland's plight. This view was based on a widely-held assumption that a nation producing unique and vital culture, one whose artists created great works of art, had a right to independence and recognition by the community of sovereign nation-states. In practical terms, this meant that the major works by recognized "national" artists were considered to be a part of the national heritage and, as such, were implicitly destined for the national museum. Their lesser pieces, which were available through exhibitions and by commission, were consequently eminently desirable and valuable both as aesthetic objects, i.e., works of art, and as patriotic icons.10 | ||||||

| This last point becomes especially important when one considers the timing of Polish Art's publication. In 1903 and 1904 Jasieński, who by then acquired a significant number of works by artists featured in the album, was involved in protracted and difficult negotiations with the National Museum in Krakow concerning the donation of his art collection. His demands included an insistence on a permanent display of the collection in specially designated rooms. Significantly, Polish Art reproduced eight paintings owned by Jasieński, euphemistically and prematurely labeled as belonging to the F. Jasieński Section of the National Museum (Oddział Muz. Nar. Im. F. Jasieńskiego) (fig.3).11 Would the National Museum have been more willing to accommodate his conditions if the public perceived the modernist works in his collection as national patrimony? Ultimately, it is difficult to answer this question. We can only speculate. If we judge by the short-term outcome, the strategy did not prove very effective. The negotiations between Jasieński and the museum broke down in 1905. They were, however, eventually renewed and his donation was accepted in 1920. By then, the collection numbered over 15,000 items. In addition to a major collection of Polish modernist works, which formed the core of the museum's nineteenth-century holdings, it included an important group of prints by European artists, a major collection of Japanese art, which included thousands of woodblock prints, an assortment of Polish ethnographic artifacts and textiles, and an extensive library. | ||||||

| In view of this coincidence of timing, it would be easy to attribute selfish motives to Jasieński's involvement with Polish Art and thereby to minimize the importance of the project. Although it may be true that Jasieński had something to gain, so did the artists featured in the album. His interests coincided with theirs. How should we view this fact? Economic considerations certainly played a role here. It is difficult to imagine that the editors and the involved artists would not have been aware of the consequences of being identified as "the greatest masters of Polish painting." We must be careful, however, not to ignore other, equally important motives. The artists of Sztuka and the sympathetic critics were quite idealistic in their views. They firmly believed that modernism was the only valid form of contemporary art practice. It established for them absolute criteria, which defined quality and ultimately determined the difference between a work of art and a painting. The former embodied absolute and transcendent values; the latter designated a particular skill-based practice. A great painting was a work of art, but not all paintings deserved such recognition. Many were considered to be just competently made images. It is not surprising, considering these views, that the artists of Sztuka considered themselves to be true artists and therefore would have had no qualms about being identified as the greatest masters of Polish painting. In their perception, and that of sympathetic critics, they were the greatest contemporary Polish painters and their practice, i.e. modernism, was synonymous with true art. By the same logic, their contemporaries may have been skilled craftsmen (they were painters), but they were not artists.12 Given this context, it is understandable why so few past painters were included in Polish Art and, perhaps most importantly, why the album removed from the narrative of the national art's history all painters, past and present, whose work could not be reconciled with modernist values. | ||||||

| What is surprising, considering the facts of the case—fifteen contemporary artists, represented by two clearly sympathetic critics, hailing themselves as the greatest Polish painters and equating national art with their own practice—is that no one objected to the album's content in the period immediately following its publication. Even though critics must have been aware of the album's omissions, there were no contemporary efforts to present an alternative view or to question the album's assumptions. The publication was well received by the Polish press despite the fact that it excluded major painters. The album's novel use of color images was duly noted and praised.13 Some reviewers questioned the selection of individual images, arguing that some pieces chosen for reproduction were not the most characteristic or the best examples of a given artist's work,14 but no one objected to the overall selection. The notices announcing the album's publication and subsequent reviews tended to reproduce, sometimes verbatim, its claims. An anonymous author reviewing the publication for the Warsaw weekly The Literary Repast (Biesiada Literacka) reported: "the editors try to encompass everything that is the best in Polish art, and to offer the public color reproductions of the finest works of our artists. Having chosen suitable commentators, they are familiarizing the readers with the entire domain of native art, as well as instructing [them] ...where to look for true beauty."15 A notice published in St. Petersburg based Country (Kraj), simply paraphrased a sentence which appeared in the album's introduction. It stated: "the editors were guided in their selection by purely artistic considerations; they tried to reproduce great works from our painting [tradition], without regard for period or stylistic direction."16 | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| How can we explain the fact that neither reviewer seemed to have noticed the partisan nature of the canon presented in Polish Art? Why did no one question the editors' motives? The character of the Polish art world in the first decade of the twentieth century provides important clues as to why this was the case. Polish Art was conceived in a period when modernism promoted by Sztuka was becoming entrenched within the Polish institutional landscape. We must remember that in the 1890s the term modernizm designated an array of stylistically diverse approaches, ranging from naturalism and impressionism to symbolism. Although these styles had ostensibly foreign origins, most directly traceable to French art, and were initially greeted by Polish critics with skepticism or even outright hostility, by 1903 they were no longer considered radical, dangerous, or alien.17 Impressionism and symbolism, in particular, which began appearing in the works of Polish artists in as early as 1890, had gained by then critical recognition and mainstream status. | ||||||

| The shift in critical reception of those stylistic tendencies had as much to do with the history of their effective defense and promotion by progressive critics, as with the changing professional status of the artists. The increased visibility of the first generation of Polish modernists at the various national and international exhibitions, a growing record of awards and honors, and finally their success in securing prestigious public commissions at home and abroad, lent considerable legitimacy to their efforts.18 Equally important in this respect was the already mentioned reform of the Krakow School of Fine Arts. Under the leadership of Julian Fałat, a capable administrator and passionate supporter of modern art, the Krakow School became the stronghold of Polish modernism. By reforming the school's curriculum to accommodate new emphasis on originality, self-expression, and formal experimentation, Fałat situated modernism within the mainstream of academic education. By hiring artists working in a modernist mode as the school's professors, he gave modern art a degree of respectability and a secure institutional base. The fact that his efforts were positively received in Vienna, and resulted in 1900 in a change of the School's official status from a preparatory institution to a fully independent art academy, was viewed by many as the ultimate confirmation of modernism's superiority over traditional academic practice. | ||||||

| The Polish modernists' skillful promotion of their work as the best contemporary Polish art was also an important factor in securing mainstream acceptance. Their decision in 1897 to form an independent exhibition society played a key role in their success. Although the Association of Polish Artists "Sztuka," had restricted membership and was, in fact, dedicated to the promotion of art practiced by its members, i.e., modernism, it nonetheless presented itself as an unbiased champion of quality, rather than of a particular tendency. The society's abbreviated name Sztuka, which in Polish means simply "Art," stressed this point. The same holds true for the organization's publicity materials and rare public statements, all of which de-emphasized its bias. Although many would insist today that Sztuka did in fact promote "the best Polish art" of the period, we should remember that the society determined what the designation "best Polish art" meant. By using modernist criteria to define quality and national significance, it relegated to an inferior status all those who did not measure up. The success of Sztuka's promotion strategy can be measured by the fact that by 1904 the society's members not only dominated domestic exhibitions, but also held a virtual monopoly on exhibitions of Polish art abroad. Despite the fact that the society represented a small percentage of Polish artists active in the first decade of the twentieth century, it was consistently called upon by the Austrian government to represent Polish cultural interests. This was the case in 1904 when Sztuka was invited by the Austrian Ministry of Culture to represent Polish art in the Austrian exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, and again in 1905 at the International Art Exhibition in Munich.19 | ||||||

| The Polish artists' active involvement in promoting their work was as much a result of ideological considerations, as of their desire to establish themselves professionally and thereby to secure comfortably middle-class lifestyles. The partition of Poland had a negative impact on the development of the Polish art market. The existence of international borders between different regions of the country restricted free movement of individuals, art works and literature. The presence of incompatible administrative structures, different currencies, import and export tariffs, and strict censorship laws aimed at suppression of Polish nationalism, created additional trade barriers, which stifled art trade and discouraged the development of commercial art galleries. As a result, until the first decade of the twentieth century, Warsaw and Krakow, the main Polish art centers, each had only one privately owned art gallery. In Warsaw, Aleksander Krywult's Salon, which opened in 1880, was the city's only privately owned commercial exhibition space. It was joined in 1904 by the Salon of Stefan Kulikowski. In Krakow, Salon Frista, operating since 1895, was joined, also in 1904, by Zygmunt Sarnecki's Salon Ars. Both Krywult's Salon and Sarnecki's Salon Ars showed modern art in addition to works by more traditional artists and played an important role in bringing modernism to the attention of the Polish public. However, when compared with the situation in Western Europe, where dealers functioned within a well-developed commercial system and were actively involved in creating a demand for the work by artists they represented, these galleries played a relatively minor role in promoting Polish modernism. In fact, one could say that by the 1900s, they were beneficiaries, rather than the creators, of a growing demand for works by Sztuka's members. | ||||||

| The de facto absence of a gallery-driven art market created a situation in which Polish artists had to assume tasks traditionally carried out by dealers. Their active role in the promotion of modernism, and hence of themselves, was necessary to their survival as professional artists. Within this context, the publication of Polish Art must be seen as a brilliant marketing strategy, one that is entirely consistent with their other efforts. If Sztuka gave Polish modernists a group identity and through its exhibitions direct access to the public, Polish Art provided them with historic validation through a direct intervention in the discourse. Their decision to target the middle class consumers by producing a "coffee-table" art book demonstrates their awareness of the need to cultivate public perception and their recognition of the inherent power and authority of the published text. | ||||||

| The success of their strategy was aided by an important factor - the absence of a pre-existing canon identifying the "foremost masters" of Polish painting. As I mentioned earlier, in 1903 the history of Polish nineteenth-century art was not yet written. Since no other publications offered alternatives to Polish Art, the album filled a discursive void. It is also important to note that even though there were several books published prior to 1903 dealing with contemporary Polish art, none identified modernism as the most important contemporary movement and none adopted Jasieński's and Cybulski's self-assured, authoritative tone. They were all produced by art critics and consisted of previously published essays. Of these Stanisław Witkiewicz's Our Art and Criticism (1891, 1892), Henryk Piątkowski's Contemporary Polish Painting (1895), and Cezary Jellenta's Gallery of the Last Few Days (1897) were the most significant examples.20 Without exception, these texts were aimed at the sophisticated, "insider" audience, rather than the broader class of educated middle-class readers targeted by Jasieński and Cybulski. They assumed a significant knowledge of Polish art, past and present, and familiarity with the major critical issues. As a result, they either contained no illustrations, as was the case with Witkiewicz's work, which was by far the most widely read and influential of the three, or had only a few black and white images. Not aspiring to the status of works of art history, these books clearly belonged within the sphere of art criticism. They reflected their authors' at times ambivalent feelings towards the newest developments in Polish contemporary art and were highly inconsistent in tone, message, and focus. Their tendency was to map the contemporary art scene inclusively, noting the emerging prominence of the modernist artists, but within a much broader and varied context of the national and even international art scene. | ||||||

| Jasieński's and Cybulski's album was different. It was unambiguous and didactic, rather than critical and subjective. It relied on color reproductions, rather than text. And, its intended readers were not art world insiders, but rather members of the urban, educated middle class. These individuals recognized art as an important aspect of culture and felt that a certain level of knowledge was required and expected of their social rank. They had sufficient discretionary income to afford the album's premium price21 and, as a group within the Polish society, were most ready to be "educated" into accepting the modernist canon. Significantly, they were also most likely to frequent art exhibitions, read art criticism, become members of the art societies, and, consequently, purchase art works. | ||||||

| From its physical appearance and serial format to its didactic tone and extensive use of illustrations, the album was designed to attract and keep the interest of those middle-class readers. It was published as a limited-run serial, consisting of fifteen issues, which appeared in roughly monthly intervals between November 1903 and February 1905. The individual issues could be purchased from bookstores or ordered by subscription. They were supposed to be collected and preserved together either in a specially designed hard cover folio or as a bound volume. The publisher made both the folio and the covers conveniently available at additional cost. If the reader chose to take the second option, the last issue of the album included a detailed note with instructions as to the manner in which the volume was to be assembled, which pages were to be discarded and which kept. | ||||||

| The serial format offered several advantages. From the point of view of publishing, it gave the editors much greater flexibility. It allowed work on the album, which involved complex tasks of managing eighteen contributors and coordinating production of the color plates, to be spread over the course of fifteen months. It also solved the potential problem of the album's high cost. The editor's desire to produce a high-quality publication, one that would establish a standard against which other domestic art publications would be judged and which, in their own words, "not only rivaled, but surpassed in many respects similar publications produced abroad," significantly raised production costs.22 The color reproductions that formed the album's nucleus were printed in Krakow from negatives, produced in Prague by the photography studio of Huśnik and Haüsler, which had to be shot from original works. This meant that the publisher had to cover the shipping expenses of transporting the artworks to Prague. Since one of the expressly stated goals of the publication was to bring Polish art to the general public, affordability was clearly an important consideration. If the album were published initially as a book, the high price would have made it prohibitively expensive. Even in the installment format it was decidedly a luxury item beyond the means of an average working class family. However, the relatively low cost of individual installments and the fact that the subscription offered buyers a substantial discount meant that the price fit comfortably within a middle-class family's budget. | ||||||

| The installment format had another merit, no less significant given the album's ideological underpinnings. The monthly release of issues meant that the album had to be collected before it assumed its final form. The anticipation of each issue, combined with the effort involved in getting them, the need to keep up with the issues one already had, and the final step of transforming the collection into a bound volume, all required a significant degree of involvement on the reader' part. In contrast, a conventional book required a single act of purchase. Once bought, it could be repeatedly perused or never again opened, becoming an empty signifier of one's erudition. The installment album offered no such immediate gratification. It protracted and slowed the reader's experience. The monthly encounter not only served a didactic function by breaking up the whole into easily manageable parts, but also invested individual issues with a value as fragments of a collection. | ||||||

|

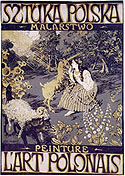

The oversized folio format (10 ½" x 14 ½") and high-quality paper were intended to give the installments a deluxe appearance.23 This effect was further enhanced by the dark green, heavy-weight paper cover, which bore a striking woodcut image (fig. 4) designed by Józef Mehoffer, a professor at the Krakow Art Academy and one of the most outspoken and active artists within the Sztuka circle. The image reiterated in symbolic terms the album's implicit message. The three main elements: the peasant girl, the unicorn, and the wolf in sheep's clothing, identified respectively Polish art, the absolute aesthetic ideal of true art, and an imposter or false art practice (one pandering to public taste and dedicated to commerce). Although the unicorn was not a traditional emblem of art, it was identified with purity, mystery, spiritual values, and authority. According to tradition, it was a fierce creature, which would only allow the touch of a pure virgin. The purity, which could be also read as superiority, was therefore an attribute of the creature and the girl. The implication of the image, given this traditional understanding of the unicorn imagery, was that national art (the peasant girl), as it was being defined by the album, was characterized by the pursuit of absolute aesthetic beauty (unicorn) and rejection of false practice (wolf in the sheep's clothing). In other words, Polish art was pure art, i.e., modernism; art that was not pure, i.e., traditional art practice, not only was not art (it was the wolf in sheep's clothing, not the unicorn), but also played no role in defining national artistic tradition. | |||||

| The success of the album's strategy depended on its ability to instill in readers the perception of historic validity and the truth of its claims. Far from wanting to reveal their bias, the editors took specific measures to create an aura of impartiality. The album did not include a single statement that explicitly endorsed modernism per se as an aesthetic tendency. Despite widespread usage of the term in contemporary criticism, the term modernizm did not appear once in the album's text. Instead, the short statements accompanying each issue stressed that the editors were completely impartial in their selection of works and artists. Even when Cybulski and Jasieński complained about the lack of support for the project from the collectors, they spoke in the name of "Art," rather than modernism. In the note accompanying the final issue of the album, which echoed Friedrich Nietzsche Thus Spake Zarathustra, they stated, "the selection of the works and artists was guided only by artistic considerations, and not a desire to please the crowd, with which no one should have to contend. Art stands on high ground, from which it does not descend. The one who desires it, who is worthy of being in its presence, must go to seek it out."24 | ||||||

| Although for us the editors' elitist characterization of art and their evident contempt for the philistine crowd betray a definite modernist position, it is far from certain that the album's buyers would have detected a particular bias. Based on the information provided in the album, a reader with a limited knowledge of contemporary art would have no way of knowing that all contemporary artists featured there were members of Sztuka. Neither would he or she know that, as far as the previous generation was concerned, the album presented a highly selective and much abbreviated version of the history of Polish nineteenth-century painting. After all, the album's full title Polish Art. Painting. 65 Reproductions of Works by Foremost Masters of Polish Painting did not seem to reveal a particular agenda. Moreover, the publication came from a legitimate source. It was published by a well-known firm and distributed by equally reputable vendors. It included well-known names. Its physical appearance and high production values engendered deference, and it was recommended by the press. | ||||||

|

The editors' decision to rely on different contributors, rather than to produce the album's text themselves, should also be seen from this perspective as a significant strategy. Besides Jasieński and Cybulski, eighteen nationally recognized art critics, writers, artists, and art historians wrote essays for Polish Art (fig. 5). Among the group were university professors from Krakow and Lvov, the director of the National Museum, and the president of the Lvov Society of the Friends of Fine Arts.25 The professional credentials and stature of the members of this group lent enormous authority to the project. Their participation implied that the album, far from actively constructing a partisan canon, was simply reproducing one that was endorsed and agreed upon by the experts; that its claim to present works by "the greatest Polish painters" was a statement of fact, rather than a value judgment made by biased art critics. | |||||

|

The introduction to the album, written by Feliks Kopera, a prominent art historian, professor at Jagiellon University, and director of the National Museum in Krakow, reinforced this impression.26 It stated that the album was produced in order to familiarize the Polish and foreign public with the "genius" of Polish art. It also repeated the editors' claim that the selection of the artists included was based on purely aesthetic and, therefore, impartial considerations. Referring to Jasieński and Cybulski, Kopera wrote,

The comparison made between Wojciech Gerson and Władysław Podkowiński is particularly interesting, in so far as it specifically addressed the issue of the album's stylistic and ideological inclusiveness. The recently deceased Gerson was the leading academic painter in Warsaw. In the 1890s he became one of the most vocal detractors of impressionism. In contrast, Podkowiński, dead since 1895, was familiar to the Polish public as a leading Polish impressionist and symbolist painter, an ardent proponent of modernism, and an enfant terrible of the Warsaw art world in the 1890s. The contrast between the august academician and the independent young radical set up a range that seemed to allow for recognition of conservative as well as progressive tendencies within national art. The note from the publisher expressed a similar view. It stated that the album was the first step in the realization of a "dream" to present "the entirety of Polish art" not only to the domestic, but also to the European public. Moreover, it proudly declared that the album did not just attempt, but in fact succeeded in reproducing works by "all foremost older and younger Polish painters."28 What the note did not state, however, was that the older generation was represented by just a few prominent figures and that those were reinvented as proto-modernists through the selection of particular works and the careful crafting of the accompanying texts. |

||||||

| The album reproduced in total sixty-one works by twenty-five different artists. The greater number of reproductions versus artists meant that while some painters appeared only once, others were represented by as many as six different images. The placement of the reproductions within the album followed no apparent logic. Although in certain instances, on the level of the individual installment, one could discern an effort to establish subtle connections between artists and works, in general, each entry, consisting of a reproduction and an introductory page, (figs. 3, 1) was a self-contained unit given semi-autonomous status within the album. The editors' decision to adopt this format, rather than the more obvious chronological arrangement, solved two difficulties. It averted the problem inherent in pairing contemporary artists with acknowledged past masters and obscured the album's focus on contemporary art. The comparison, in which the contemporaries would have been burdened by the lack of temporal distance, (not yet having passed the "test of history"), was never made. Instead, the reader was presented with a seemingly random arrangement that in effect suppressed hierarchical distinctions and presented individual artists, irrespective of differences in age, background, or approach to painting, as equals. Whether they were already acclaimed, which was the case with Jan Matejko to whom the editors dedicated an entire issue, or were at the beginning of their careers, as was the case with Weiss, the youngest painter included, the featured painters were all presented as great artists belonging to an transcendent realm of pure art. | ||||||

| The issue of "influence," seemingly unavoidable within a canonical construction, was, likewise, downplayed. Since the layout made no distinction between the deans of Polish painting and the relative newcomers, the artists' portraits, which appeared at the top of the introductory page, created an egalitarian pantheon of national art heroes. Although individual essays sometimes pointed out that a particular painter studied with another, the emphasis was placed not on their relationship, but on the pupil's ability to develop his own unique, personal vision. Irrespective of whether the text dealt with an older or younger artist, it inevitably stressed independence and originality. It implied that what linked the featured painters was not subject matter or stylistic continuity (qualities that traditionally defined national schools), but their shared dedication to art, sensitivity to formal issues, superior talent, if not genius, and above all, originality. The last point, made repeatedly in the album, echoed the claims made by sympathizers of modernism in the 1890s. Progressive critics, who defended modern art against charges of "foreignness," argued that national character did not depend on the work's subject matter. Any subject executed in any style could be legitimately thought of as national as long as the artist felt himself to be a Pole. Since content did not determine the national value of a work, the sole criterion of evaluation was the work's form. In the end, what mattered was not what was depicted, but how the image was made. The ability to arrange colors, lines, and shapes, to manipulate light and create illusion of depth, to use texture and brushwork for expressive purpose, and to explore the sensuality of the materials were the only criteria one could use to determine quality in painting. All other considerations, though not entirely irrelevant, had only secondary importance. | ||||||

| This argument made on behalf of individual artists and reiterated in the album's introduction provided a consistent rationale for the selection as well as omission of various painters. The reliance on formal analysis seemed to offer a reliable, unbiased, and fair gauge for evaluation. A painting was either well-made or it was not. A painter either applied his skills in an original manner, creating works that were truly his own, or he was a mere imitator, a second-rate follower of someone else's path. In theory, all claims made in reference to actual paintings were empirically verifiable. One could check the statements against the evidence of the work. The artists whose paintings exhibited the requisite formal excellence were masters of their medium and therefore were included in the album; those whose work did not were excluded. The reality, however, was much more complicated. A reader, whose experience with actual paintings would have been most likely limited to an occasional visit to a local art exhibition, would have had no way of evaluating either the accuracy of individual statements or the fairness of the selection. The authors' authoritative tone, reliance on specialized vocabulary, and frequent references to works that were not even illustrated in the album, coupled with the average reader's lack of familiarity with art, meant that what was being asserted would have been simply accepted at face value. This had significant repercussions, since what was left unsaid and unacknowledged was that that the formal standard used was a product of a particular artistic practice. It was defined through modernist criteria, which though different from the academic ones, were no less subjective in their assumptions. | ||||||

|

When applied to the past, the formal standard became a means of fashioning an unimpeachable national lineage for modernism. Although by 1903 the view that modern art was a foreign import was no longer prevalent, the need to link contemporary art practice to the national tradition was still keenly felt. The political reality of Poland's partition meant that all artists, irrespective of what their specific interests might have been, had to frame their practice within the context of a nationalist discourse. By arguing that formal attributes determined quality irrespective of time period, Jasieński and Cybulski effectively divested modernism of its recent origins and foreign pedigree, presenting it as a culmination of tendencies present in works of the great past Polish painters. Individual essays implicitly identified past painters, who embraced explicitly patriotic subject matter and were well known to the Polish public, as precursors of modernism. A case in point is the treatment accorded Jan Matejko, the most celebrated Polish painter of the nineteenth century, in the album. In the 1870s and 1880s, Matejko won admiration of the critics and a cult-like following from the Polish public by producing a series of large-scale canvases commemorating momentous events in Polish history. Frequently carrying thinly veiled references to the country's political situation, his dramatic compositions dazzled audiences with a spectacular display of academic virtuosity and historicist detail. Endlessly reproduced in inexpensive prints, postcards, and newspapers, they were considered the epitome of national art. Although the progressive critics frequently attacked Matejko during his life, after his death in 1993 be became an untouchable figure, someone who no longer posed any threat and deserved certain deference. Jasieński and Cybulski, far from wishing to exclude Matejko, gave him a place of honor within the album. They reproduced five of his canvases and dedicated an entire issue to one of his most famous and most patriotic compositions The Prussian Oath (1882) (fig. 6). The October 1904 number included a black and white photograph of the entire paining and four full-color details. No other artist received such a treatment. The reasons for emphasizing Matejko in such a way are obvious, given the painter's fame and popular appeal of his work. The canon of Polish painting had to include him. If it did not, the public and critics would certainly reject it. On the other hand, if the modernists could claim Matejko as "one of their own," reinventing him as a proto-modernist, they could surely argue that modernism was a native phenomenon. | |||||

| Within the album, Matejko and other past masters were subjected to creative reinterpretation. The authors of the individual essays emphasized painterly qualities of their work. They drew readers' attention to their individualistic or unorthodox approach, which within the text signified originality and sincerity, while ignoring their dependence on academic conventions. Although the explicitly patriotic content of their works was noted, it was de-emphasized in the general assessment of the artists' contribution. This argument was reinforced visually through the selection of reproduced works. The paintings, watercolors, and pastels that formed the core of the album were not necessarily the artists' best-known or most highly regarded works. The notes accompanying each issue blamed that situation on reluctant collectors, who failed to support the project. Since the owners not only had to grant permission to reproduce the image, but also had to lend the work itself, some found the prospect of sending a painting on a hazardous journey, with the possibility of accidental damage or even loss, not very appealing and refused to cooperate. However, as plausible as this explanation sounds, it is interesting to note that when it came to the painters of the generation that immediately preceded the modernists, the reproduced works tended to be some of the most "modern" ones that the artist had painted. The more conventionally academic images, which in the case of painters such as Wojciech Gerson or Witold Pruszkowski constituted virtually the entire body of their work, were ignored, while completely uncharacteristic, but formally more experimental works were selected. In the case of Gerson, the album reproduced two of his last landscapes (one of which is fig. 7), not the academic nudes or history paintings (fig. 8) for which the artist was best known and which should have been just as easy for the editors to obtain. For Pruszkowski, who made his reputation as a painter of peasant subjects and folk tales (fig. 9), the editors selected one of his last and least characteristic canvases, A Vision (1890) (fig. 10), which, in its mystical subject matter and loosely handled brushwork, stood out as a dramatic departure for the artist. Clearly, considerations other than the ability to secure originals were at play. If, in fact, one of the goals of the project were to construct a native genealogy for Polish modernism, then the inclusion of paintings that could be seen as modernist in character, by artists whose work in general did not embrace modernist values, would have given credence to the argument. The choices the editors made seemed to provide concrete visual evidence of the continuity within the national artistic tradition and the historic validity of modernist claims. | ||||||

| In the end, did the album create an enduring modernist canon? The answer to that question is very much, yes. In order to gain acceptance, a value judgment must have a basis in reality. By 1903 modernism promoted by Sztuka was rapidly entrenching itself as orthodoxy. The members of the society controlled art education and dominated art exhibitions in Poland. Through international shows organized by Sztuka, they made Polish art synonymous with their own practice abroad. Within the contemporary art criticism, modernism signified quality. By 1903, artists who were not considered sufficiently "modern" were being relegated to the periphery of the art world. The modernist canon presented in Polish Art would have seemed "correct," even to relatively well-informed members of the public. It included artists whose work was regularly shown at art exhibitions and discussed in the press, who held prestigious academic positions, whose paintings could be found at the National Museum, and who were, quite literally the masters of Polish painting. | ||||||

| When a statement is presented in an authoritative form to readers lacking the confidence and the knowledge to evaluate it; when it seems to reflect reality; moreover, when it is unopposed and repeated, it becomes the dominant paradigm. This is what, I would like to suggest, happened in the case of Polish Art. The editors' decision to market the album to the general public virtually guaranteed that its readers would not question its assumptions. The careful staging of the readers' experience—from lavish physical appearance, installment format, and premium price, to reliance on expert contributors, didactic tone, and distribution through well-known bookstores—was meant to inspire trust. What is more, the album's authors took an important step to ensure the endurance of their canon. The last issue of the series included an announcement that the album was available for purchase as a single volume. Late the same year, a miniature, black and white, single volume version of the album was published. It included an announcement for a second, full-size edition, which was published in 1908. Released in twelve instead of fifteen issues, the second edition included fewer images (fifty instead of sixty-five) and lacked the lavish cover. It was explicitly promoted as the more affordable version of the original album. The text promoting the publication, which appeared on the inside cover of each issue, emphasized this point. It stated that the second edition of Polish Art was "elegant, yet so inexpensive, so extraordinarily inexpensive that it [was] within reach of even those least affluent."[emphasis in the original text]29 The full run of this series cost only 12 Austrian Kronen, compared to 40 for the fist edition. While it seems certain that the lower price was intended to attract more buyers, no records exist, unfortunately, that could tell us if that goal was realized. | ||||||

| The album Polish Art was never viewed as a brilliant marketing device. It went through multiple editions, and its version of the canon was adopted and perpetuated by other publications. The point made earlier about the album's editors filling a discursive void is worth reiterating here. The absence of an established national canon allowed Polish modernists to construct one in which they, themselves, were prominently featured. The fact that Polish Art was the first text to define the canon of Polish nineteenth-century painters made it difficult, if not impossible, to dislodge. The correspondence with contemporary reality, the inclusion of past painters who were already esteemed by the critics and public, combined with the rhetoric of "great art" and reliance on seemingly neutral evaluative criteria, gave Polish Art considerable credibility, even among later generations of scholars. The absence of a well-organized, articulate opposition also helped. By 1903, the Polish press coverage of contemporary art was dominated by progressive art critics. The few writers who were less than enthusiastic about modern art did not have the authority or name recognition to mount a successful challenge. They remained silent. The consequences of Polish Art's acceptance are still with us. Although one can find today artists who did not make it into the album in Polish museum collections and accounts of the period, they are clearly presented as figures of secondary importance. Even Olga Boznańska, an important modernist painter and a member of Sztuka, tends to be treated as a maverick outsider. Is the fact that she was omitted from Polish Art partly responsible? We can only speculate. Certainly, a number of different factors played a role. However, the observations that histories are written by the winners, not the losers, and that discourse is defined by those able to participate in it, certainly apply here. The fact remains that the great heroes of Polish nineteenth-century painting, the artists without whom any survey of the period would be unthinkable, continue to be the painters featured in Polish Art. Without denying their rightful place within art history, it behooves us as art historians to be more conscious of the process by which they entered the canon. | ||||||

| The history of the album Polish Art unambiguously reveals that Polish artists were actively engaged in promoting their own work and were remarkably successful in their endeavors. Their activities affected not only contemporary perception, but also, remarkably, shaped the subsequent production of art historical discourse. I would like to suggest that the same conclusion can be drawn with regard to other contexts in which artists and critics engaged in strategic production of canonical art history. Books such as Paul Signac's From Eugene Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism (1899) and Julius Meier-Graefe's The History of the Development of Modern Art (1904) should be considered, from this perspective, prime examples of the genre to which Polish Art belongs and which I propose to call "strategic art history." If we include in this category texts produced on behalf of a single artist, then the works of critics such as Roger Fry also should be considered. An examination of the tremendous impact of these and other similar publications on art historical discourse, on paradigmatic explanations, designations of centers and peripheries, and, ultimately, judgments concerning value and historic significance, is long overdue. A systematic and focused investigation of where and how specific canons originate, who creates them and why—in other words, of the historic, political, ideological, and market conditions of their production—will allow us not only to historicize canonical art history, but also to give credit where credit is due; namely, recognize artists' and critics' agency within the process of value conferral and, hence, production of art canons. | ||||||

|

1. The album reproduced works by seven out of eight founding members of Sztuka: Teodor Axentowicz, Józef Chełmoński, Jacek Malczewski, Józef Mehoffer, Jan Stanisławski, Leon Wyczółkowski, and Stanisław Wyspiański. Only Antoni Piotrowski was not included. The other members of Sztuka, whose works were reproduced were: Stanisław Dębicki, Julian Fałat, Stanisław Masłowski, Józef Pankiewicz, Włodzimierz Tetmajer (joined as regular members in 1897), Wojciech Weiss (joined as regular member in 1900), Ferdynand Ruszczyc (joined as regular member in 1901), and Karol Tichy (joined as regular member in 1902). The album also reproduced works by three recently deceased artists who were considered by the critics to be "modern": brothers Maksymilian Gierymski and Alexander Gierymski, and Władysław Podkowiński. Of the artists of the older generation in a traditional mode, the album included only seven individuals: Piotr Michałowski, Artur Grottger, Henryk Rodakowski, Józef Kossak, Jan Matejko, Wojciech Gerson, and Witold Pruszkowski. 2. In 1895, Julian Fałat, an artist sympathetic to modernism, was appointed as the director of the Krakow School of Fine Arts. In the first two years of his administration, Fałat hired four modernist artists, Axentowicz, Wyczółkowski, Malczewski and Stanisławski, to implement a radically redesigned curriculum. These four artists would become the driving force behind the founding of Sztuka in 1897. Throughout his tenure, Fałat consistently selected modernists for newly established or vacated faculty positions. As a result, over the next thirteen years, he transformed the School into a modernist academy. Konstanty Laszczka and Stanisław Naukowski were hired in 1899, Mehoffer in 1900, Wyspiański in 1902, Xawery Dunikowski in 1904, Pankiewicz in 1906, Ruszczyc in 1907, and Weiss in 1908. Józef Dutkiewicz et al., Materiały do dziejów Akademii Sztuk Pięknych w Krakowie, 1895-1939, Źródła do dziejów sztuki Polskiej, vol. 14 (Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy Imienia Ossolińskich, 1969), pp. 178-202. 3. Jerzy Mycielski, Sto lat dziejów malarstwa w Polsce, 1760-1860. Z okazji wystawy retrospektywnej malarstwa polskiego we Lwowie1894 r. (Krakow: Drukarnia "Czasu," 1897). 4. Jasieński's art criticism appeared in Czas, Chimera, Lamus, Mięsiecznik Literacki i Artystyczny, Naprzód, Nowa Reforma, Głos Narodu, Ilustrowany Kurier Codzienny, Kurier Warszawski, and Słowo Polskie. Cybulski was closely associated with the short-lived modernist Kraków periodical Źycie. He also contributed criticism to Ilustracja Polska, Krytyka, Tygodnik Slowa Polskiego, Tygodnik Ilustrowany and Tydzień, where he published a regular column from 1902 to 1904. 5. Irena Kossowska, (Krakow: Universitas, 2000), pp. 48, 59. 6. Cybulski, who was twenty-four in 1902, was much younger than the artists featured in the album. With the exception of Weiss, who was twenty-seven in 1902, they were all in their mid-30s and mid-to late-40s. Chełmoński, the oldest member of the group, was fifty-three and Wyczółkowski fifty. 7. Text on the inside cover of Sztuka Polska, 2nd edition, No. 10 (1908). 8. "Od Wydawcy," Sztuka Polska, Year I, no. 1 (December 1903). The same text appeared in nos. 1-3. 9. Harrison White and Cynthia White, Canvases and Careers. Institutional Change in the French Painting World (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993). 10. I consciously use the pronoun "he," rather than a gender-neutral designation, to signal a definite gender bias. Although in 1904 Sztuka had one female member, Olga Boznańska, she was not included in Polish Art. Neither were any other women artists. Although it is difficult to state with any degree of certainty why this was the case, the album's reliance on the idea of individual genius, a highly gender-specific concept in the nineteenth century, is most likely to blame. This topic certainly deserves further consideration and analysis, which unfortunately falls outside the scope of this essay. 11. Jasieński's collection included works by Wyczółkowski, Pankiewicz, Podkowiński, Wyspiański, Malczewski, Mehoffer, Masłowski, Chełmoński, Constanty Laszczka, Fałat, Stanisławski, Dębicki, and Weiss. For more on Jasieński's negotiations with the National Museum see Janina Wiercińska, "Feliks Jasieński (Manggha) jako działacz artystyczny i kolekcjoner," in Aleksander Wojciechowski, ed. Polskie Źycie artystyczne w latach 1890-1914 (Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1967), p. 214. 12. These views recall the arguments used by the French academic artists in the seventeenth century to claim their superiority over the maîtrise and are consistent with my argument that the artists of Sztuka positioned themselves to function as a modernist academy. See Paul Duro, The Academy and the Limits of Painting in Seventeenth-Century France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997). 13. Only one review questioned the wisdom of using color instead of black and white reproductions. See Zb. Brodzki, "Literatura i sztuka. 'Sztuka Polska'," Prawda no. 6 (5/18 February, 1905), p. 69. 14. This criticism was most forcefully made in the Warsaw weekly Prawda by a reviewer identified as "Sierp." Sierp. "Literatura i sztuka. Ze sztuki. Wydawnictwo 'Sztuka Polska'", Prawda no. 7 (31 January/13 February, 1904), pp. 81-82. 15. "Wydawnictwo artystyczne 'Sztuka Polska'," Biesiada Literacka, no. 28 (8 July/25 August, 1904), p. 40. 16. L. "Sztuka Polska," Źycie i Sztuka. Pismo Dodatkowe Ilustromane, Kraj nos. 2-3 (21 January/8 February, 1905), p. 15. 17. For a detailed account of the process of legitimization and nationalization of modern art in Polish art criticism see the author's "Between the Nation and the World: Nationalism and Emergence of Polish Modern Art," Centropa 1, no.3 (September 2001), pp. 165-179. 18. Polish modernists regularly exhibited at the Warsaw Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts, and its Krakow counterpart, the Society of the Friends of Fine Arts. The artists also showed at other, less prestigious venues, such as Krywult's Art Salon in Warsaw. Even though in general these activities did not lead to significant sales, they did ensure public exposure and significant press coverage. They also sent works to events that accepted international submissions, the most important of these being the French Salon, and actively sought representation with foreign art dealers. For further discussion of the modernists' professional accomplishments see Anna Brzyski, "Modern Art and Nationalism in Fin de Siècle Poland" (Ph.D. Diss.: University of Chicago, 1999), pp. 127-133. 19. For the discussion of Sztuka's participation in the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair, see the author's "Unsere Polen...: Polish Artists and the Vienna Secession, 1897-1904" in Michelle Facos and Sharon Hirsh, eds. Art and National Identity at the Turn of the Century. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 65-89. For the reference on Sztuka's participation in the International Art Exhibition in Munich see Franciszek Klein, "Zarys historyczny Towarzystwa Artystów Polskich "Sztuka"," in Sztuka, 1897-1922 (Kraków: H. Altenberg & Gubrynowicz i Syn, 1922), pp. x-xi. 20. Stanisław Witkiewicz, Sztuka i krytyka u nas (Kraków: L. Anczyc i Spółka, 1891); Henryk Piątkowski, Polskie malarstwo współczesne: Szkice i notaty (St. Petersburg: Księgarnia K. Grendyszyńskiego, 1895); Cezary Jellenta, Galeria ostatnich dni: Wizerunki, rozbiory, pomysły (Kraków: L. Anczyc i Spółka, 1897). 21. The annual subscription (12 issues) cost 12 Russian Rubles. The individual issues cost 1.5 Rubles. The full bound set was available for 20 Rubles or 40 Austrian Kronen. 22. "Od Wydawcy," Sztuka Polska Year I, no. 1 (December 1903). The same text appeared in nos. 1-3. 23. The discrepancy between numbers of reproductions is due to the fact that issue 11 (October 1904) was dedicated in its entirety to Jan Matejko, the most famous Polish painter of the 19th century. It reproduced Matejko's Self Portrait and Prussian Oath, in black and white, and included four full color details of the latter painting. The only other work reproduced in black and white in the album was Maximilian Gierymski's canvas The Eighteenth-Century Hunt, which appeared in the album's final issue. Year II, no. 15 (February 1906). 24. "Od Redakcji," Sztuka Polska, Year II, no. 15 (February 1906). 25. The album included texts by Feliks Jasieński (11)*, Adam Łada Cybulski (5), Stanisław Witkiewicz (10), Konstanty Marian Górski (8), Stanisław Lack (5), Wilhelm Mitarski (4), Jan Kleczyński (3), Tadeusz Źuk-Skarszewski (3), Tadeusz Jaroszyński (2), Miriam (Zenon Przesmycki) (2), Eligiusz. Niewiadomski (2), Jan Bołoz Antoniewicz (1), Józef Chełmoński(1), Stanisław Estreicher (1), Feliks Jabłczyński (1) Feliks Kopera (foreword), Kazimierz Mokłowski (1), Maryan Olszewski (1), Maryan Sokołowski (1), and Stanisław Tarnowski (1). 26. The introduction was published in the final, fifteenth issue of the album, which appeared in February 1906. Since it was published when the album was completed, it can be assumed that Kopera was aware of the actual, rather than planned, scope. His statements, therefore, must be taken as indications of his desire to present the album as a comprehensive work. 27. Keliks Kopera, "Przedmowa," Sztuka Polska, Year II, no. 15 (February 1906). In the original series, Kopera's introduction appeared in the last issue. In the bound edition, it appeared at the beginning of the book. 28. Emphasis appears in the original text. "Od Wydawcy," Sztuka Polska, Year I, no. 1 (December 1903). The same text appeared in nos. 1-3. 29. Text on the inside cover of Sztuka Polska, 2nd edition, No. 10 (1908)

|