The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

“All I want to save is my paintings,” Gustave Courbet wrote from Ornans to his friend Jules Castagnary on February 9, 1873.[1] The artist was rightly worried that the French Chamber would decide to seize all his real estate and personal assets to finance the reconstruction of the Vendôme Column. A prominent member of the Paris Commune, Courbet had played a fundamental role in the destruction of that symbol of Napoleonic Rule. Immediately after the event, in 1871, the Versailles War Council had sentenced him to a fine of five hundred francs and six months imprisonment. Subsequently, the new government of the Third Republic wanted to make him financially responsible for the Column’s reconstruction. While Courbet was of the opinion that he could not be punished twice for the same offense, he nevertheless immediately took the necessary precautions to safeguard his property. In another letter to Castagnary, he wrote, “we will be decentralizing and it won’t matter much if I do not live in France.”[2] In the midst of these turbulent months Courbet was making ambitious plans for an exposition complète[3] of his works at the 1873 World Exposition in Vienna. International exposure was certainly one of his motivations; getting his work out of France may have been another one. It is unclear how he hoped to realize his plans, although he did manage to get his programmatic paintings The Artist’s Studio (fig. 1) and A Burial at Ornans (1850, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) shipped to Vienna. These monumental paintings, together with nine others, were neither exhibited in the French pavilion of the World Exposition nor in any other Exposition-related venue. Instead, they were presented in a show organized by the now-obscure Österreichischer Kunstverein (Austrian Art Association). Under what circumstances this occurred and how Courbet’s works were received in Vienna is what this article proposes to explore. This brief but crucial period of Courbet’s career provides an opportunity to better understand the role of art dealers and art associations in transnational exhibition practices of the late 19th century.

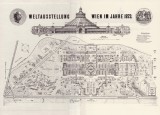

In the early 1870s, during a period when Paris was characterized by violent political conflict between Republicans and Monarchists, Vienna, the imperial capital on the Danube, developed into the leading artistic center in central Europe. The Austro-Hungarian monarchy was enjoying a never-before-experienced economic boom that made itself felt in a general spirit of optimism on the art market and gave rise to an enormous amount of building activity. The Viennese Ringstraße, one of the largest building sites in Europe at the time, was gradually taking shape. Even today, representative buildings such as the Court Opera, Court Museums, Parliament, and Stock Exchange give an impression of the euphoria of the period. Half a century after the Congress of Vienna, it appeared that Austria had, once again, found a cultural mission in Europe. At the high point of the liberal era of the so-called Gründerzeit the country had great hopes for the 1873 World Exposition—the fifth to be held and the first in a German-speaking country.

Initially, it was uncertain that France would actually take part in the Vienna World Exposition because of its unstable political and economic situation. But France once again showed that it was prepared to defend its reputation as the cultural nation par excellence. Its number of fine arts exhibits far exceeded those of any other country. France presented 1,573 of the total of 6,600 works displayed; it was followed by Germany with 1,026 and Austria with 869. The 247 medals France was awarded trumped those of both the host country and the German Reich.[4] Edmond du Sommerard, the French delegate to the Exposition responsible for the fine arts, encouraged private collectors and art dealers to supply works. He even had restrictions on loans from the Musée du Luxembourg lifted.[5] Austrian critics considered this another proof of centuries-old exemplary state support for the arts in France. Decades later, Ludwig Hevesi still reported, full of admiration, how Léon Gambetta, notwithstanding the extreme political distress following Napoleon III’s defeat at the battle of Sedan, had created a French art ministry: “He considered Antonin Proust just as important as the finance minister who had to secure the billions. The aim was to assure France of its leading role in art after it no longer marched in the vanguard of politics.”[6]

For a short time, Courbet played with the idea of presenting some of his works at the official French exhibition in the Viennese Prater, the large public park (fig. 2). In a letter written on January 23, 1873, a few days before the official deadline for submissions, Castagnary encouraged him: “You have to exhibit in Vienna by all means. Not in Paris, not even in France, but abroad, everywhere; being present must become your line of conduct.”[7] Yet Courbet’s plan of taking part in the nation’s exhibition met an abrupt end on January 31, 1873 when Castagnary informed the artist that Edmond du Sommerard had categorically rejected his participation.[8] As had been the case at the Paris Universal Expositions of 1855 and 1867, when Courbet had self-assuredly staged displays of his works in his own pavilion on the outskirts of the exhibition site, the only option open to him in Vienna was to look for a private alternative. However, from his retreat in Ornans it must have been difficult for Courbet to organize a competing exhibition in Vienna on his own; he had to rely on assistance from friends, and he placed his trust in the Parisian art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel with whom his commercial relationship had flourished in the past years. In February 1872, Courbet had sold him 24 paintings for 50,000 francs; a year later he disposed of another group for an estimated 37,000 to 50,000 francs.[9] Today, it is difficult to understand how a strict Catholic and monarchist like Durand-Ruel could support a Communard like Courbet. Indeed, in the year of the Vienna World Exposition, the dealer had publicly proclaimed his support for the Comte de Chambord, the legitimist pretender to the throne: “Deals were only stopped out of fear of falling back into the hands of the Republicans and we all hope—as Frenchmen and businessmen—of re-establishing the hereditary monarchy that alone can put an end to our troubles.”[10] Paul Durand-Ruel, who later became legendary as the Impressionists’ art dealer, not only provided works for the French World Exposition pavilion, where he managed to smuggle in an early Manet (Old Man Reading, 1861, City Art Museum, St. Louis),[11] he also sent an employee to Vienna who offered a collection of works by French masters for sale in a rented gallery on Elisabethstraße. In his memoirs, the art dealer reminisces: “In fact, it included many splendid works such as my large-scale 'Sardanapalus’ by Delacroix and many other pictures by our greatest masters, which I had bought at recent sales, as well as other interesting canvases capable of giving a distinguished and well-founded impression of our fine French school.”[12] Advertisements in the press show that in the fall he exhibited Sardanapalus (1827, Musée du Louvre, Paris) again at the Österreichischer Kunstverein, the venue that hosted Courbet’s paintings during the Exposition. Although Durand-Ruel was not able to organize for Courbet the retrospective the artist had hoped for, shipping lists suggest that among other French masters three Courbet landscapes may have been shown in the rented Viennese gallery.[13]

Paul Durand-Ruel must have recognized that the prospects for financially successful private initiatives on the fringe of the World Fair were extremely promising. Decades later, the Viennese art dealer Hugo Othmar Miethke, in an interview he gave to Berta Zuckerkandl, recalled the spending spree that had taken place in the “famous Gründerjahr” 1872, a time when it was, apparently, more difficult to acquire pictures than to sell them. “I believe that this will remain a unique case in the history of the Viennese art trade,” was how Miethke described it in 1905.[14] Months before the opening of the World Exposition, there was a fierce struggle between the Austrian art dealers Alexander Posonyi and Miethke & Wawra over which of them would rent the Künstlerhaus—the most prominent private exhibition hall in the city—during the World Exposition. Miethke & Wawra had commissioned the celebrated Viennese artist Hans Makart to create the painting Venice Pays Homage to Caterina Cornaro (fig. 3), measuring four by ten meters, for the reported price of 80,000 gulden—or had at least acquired the work for that price at an early stage.[15] This painting was intended to be the main draw at the firm’s sales exhibition. Spurred on by the fabulous profits of the previous year, Miethke & Wawra were also prepared to make the considerable amount of 38,000 Gulden available to rent the Künstlerhaus during the World Exposition.[16] According to a report in the Neue Freie Presse, after Miethke & Wawra had secured the lease, Alexander Posonyi offered to pay an even higher rent, but the board—hoping, perhaps, that Miethke & Wawra’s exhibition, centered on Makart’s Caterina Cornaro, would provide a more dignified representation of Austrian artists—decided “to adhere, de jure, to the lease agreed on in a correct procedure with the mentioned company.”[17] In any case, the theatrical staging of the main attraction proved to be a great hit with the public. The art journal Kunstchronik noted that because the Künstlerhaus had been secured as the venue, “the unfortunate idea of showing the painting in a special booth in the Prater” had been dropped.[18] If there ever was the idea of an independent exhibition on the fair grounds, it was probably based on the famous example set by Courbet.

While it is not absolutely clear how Gustave Courbet came into contact with the Österreichischer Kunstverein, it is probable that Jules Castagnary, and not Paul Durand-Ruel, suggested this alternative exhibition venue.[19] The Kunstverein, in the baroque Schönbrunnerhaus on Tuchlauben, was founded in 1850 and had been the top address for public exhibitions in the city for decades (fig. 4). Its concept of changing some of the pictures on display in its permanent exhibitions each month was greeted with great approval by the public, and it was especially known for entertaining its audience with globetrotting paintings, such as Paul Delaroche’s Napoleon I in Fontainebleau (1845, exhibited 1851).[20] Indeed, it was notorious in the press as the site for theatrical displays of sensational travelling paintings—a practice from which the Genossenschaft bildender Künstler Wiens, founded in 1861, tried to distinguish itself by mounting exhibitions of its local members. While, according to a report in the German art newspaper Dioskuren in 1871, the Genossenschaft was directing all its efforts towards preparing the annual exhibition in the Künstlerhaus, “the directors of the Österr. Kunstverein . . . indulge in creating new interest every month and attracting the curious public with unusual and rare works. This satisfies the mass seeking novelties, but the [Genossenschaft bildender Künstler Wiens] provides those who wish to have a deeper understanding, and love of art with what they are seeking.”[21] The differences between the two societies were actually not so straightforward. In a letter dated March 28, 1872, the director of the Kunstverein minimized the oft-cited competitive situation, writing that the same artistically-inclined public visited the exhibitions in the two houses.[22] The Genossenschaft, however, owned the better-suited, sky-lit exhibition spaces in the Künstlerhaus that had been erected specifically for exhibition purposes on Karlsplatz in 1868. While a “corruptive cosmopolitanism” was considered a significant shortcoming of the Kunstverein, the Genossenschaft, as a group of creators rather than consumers, originally paid more attention to protecting the market for local artists.[23]

In an undated draft letter to the director of the Kunstverein, Gustave Courbet stated that Austria had always been “congenial” towards him: “As I consider that the manifestation of art must be free and of all nations, I turn to you and your committee [to see] whether you can authorize me to send you the works that I will have completed specifically for you by the above-named deadline.”[24] Courbet had high-flying plans for Vienna. He wanted to challenge the official French presentation on the World Exposition fairgrounds with sixty works of all genres. The entrepreneurial artist proudly drew attention to the fact that his exhibition was being organized by the Kunstverein without any kind of state support. He once again dreamed of a comprehensive retrospective exhibition of his oeuvre. Courbet wrote to his assistant: “I’ll go to the Vienna exhibition, where I will be having a complete show of my work at the Art Union of the young [artists].”[25] In no way was it a “union of young artists.” The Österreichischer Kunstverein was a consumers’ union with several thousand members who paid an annual fee to take part in a lottery to win a painting and had the right to obtain prints. Although Courbet thought a great deal about the selection of works he intended to present to the Viennese public, it was inconceivable that the Kunstverein would present a show of paintings by a single artist. While Miethke and Makart had full control over the way works were perceived in the rented Künstlerhaus, Courbet’s pictures were lumped together in the Kunstverein with a wide, diverse mass of other artworks.

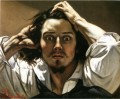

Due to space limitations, it was initially only possible to exhibit six of the eleven canvases brought over from Paris.[26]The Painter’s Studio (1855, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), The Wrestlers (1853, Szépmüvészeti Museum, Budapest), Alms of a Beggar (1868, Burrell Collection, Glasgow), Portrait of the Artist (fig. 5), Portrait of General Cluseret (whereabouts unknown), and a Bather had to hold their own among the 152 works in the show.[27] Although Courbet had originally planned a balanced presentation of his oeuvre, precisely the one-sidedness of the selection was ultimately criticized. The Kunstchronik reported that both artists and lay persons stood shaking their heads in front of the figural paintings, puzzled in their attempts to create a connection between the works on display and the painter’s reputation:

It would have been important in Vienna, where the artist was being shown with a large number of works for the first time, for a series of pictures of different genres and from different periods to be shown alongside each other in order to provide a broader foundation for the public to judge the value of Courbet as a painter; but here it began with the worst, possibly in order to follow with the better and then the good in a purely commercial way.[28]

The newspaper Fremden-Blatt advised its readers to wait before making a final judgment in view of the fact that not all of the works Courbet had provided had yet been exhibited.[29] One could only hope that important paintings, still stored in the Kunstverein’s warehouse, would take the place of those on display. A letter by the painter Carl Schuch reported that the Burial at Ornans was actually hung in June.[30] However, Castagnary’s advice, given in wise foresight, of not showing paintings such as the Burial in the Kunstverein turned out to be right: “It has its time and its history in France. It must stay here . . . in order not to give renewed impetus to old arguments.”[31] Almost all of the works shown could be interpreted as political statements. The critics tended to see them as the transgressions of a probably important, but rough and untrained talent. The Kunstchronik noted that his Burial as well as his Studio offered “only a random lineup of figures lacking any kind of psychological coherence.”[32] In the early 1850s, the critic wrote, a small group of Courbet’s admirers had proclaimed that what appeared to be the shortcomings of his talent were actually a reformatory satire on academic emptiness. But the crude and ugly could not be the ideal of art as a whole. The German-language critics usually recognized the high level of technical mastery of the “official” French artists in the World Exposition pavilion, although the tendency toward superficial effects at the expense of profundity of content was often chastised as “chicism.”[33] But not even technical mastery, a hallmark of French art, could be found in Courbet’s figural pictures. The reviewer of the Dioskuren, for example, described Alms of a Beggar (fig. 6) as “the most off-putting, incompetent painting to have been seen in a long time.”[34] Critics regretted that there were not more landscapes and paintings of animals on display in the Kunstverein as these, in particular, had made Courbet’s reputation as an artist. The reviewer in the Kunstchronik even went so far as to say that, in his Studio, Courbet had unwittingly treated himself with irony as, in this allegory, the artist is shown painting a landscape—seeming to agree with the reviewer that “his brush is quite simply not made for showing people, it can only be used fruitfully in landscapes and in pictures of animals.”[35]

Many of the newspapers published in Vienna at the time, including the liberal Neue Freie Presse, did not even think Courbet worth reviewing.[36] On the other hand, he could not simply be ignored, nor could one pretend, as Emile Mario Bacano expressed in the Tages-Presse, that he did not exist: “He makes too much noise for that—with his voice, with his beliefs, with his brush.”[37] Bacano criticized what he considered Courbet’s ostentatious, arrogantly large, programmatic paintings. Yet the public of the Österreichischer Kunstverein was completely accustomed to colossal paintings intended as marketing tools. Such sensational pictures that circulated by way of the widely ramified channels of the Central European societies stopped over in Vienna at regular intervals. The art historian Rudolf von Eitelberger repeatedly railed against the “leveling effect of the society and trade pictures” that, through their subjects alone, “reveal the loud secret that they have been painted without any commission, that they are not intended for any purpose of the state.”[38] The commercialization of painting was the price paid for dismissing the artist from the service of the state, court, and church. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon had addressed the same problem in respect to Courbet when he asked: “But just who did Monsieur Courbet intend this picture [the Burial] for? Where would be the right place for it? Definitely not in a church, where it would be an insult; nor in a school, a town hall, or even a theatre. It would take a special kind of gentleman with a taste for curiosities to even think of letting it into his attic and he would be careful not to hang it in his salon.”[39]

The main attraction of the exhibition in the Österreichischer Kunstverein was not Gustave Courbet’s Studio but Wilhelm Kaulbach’s Nero Persecuting the Christians (fig. 7). Kaulbach’s work was used to promote the show in paid advertisements in the daily newspapers, which usually did not even mention Courbet (fig. 8). Intentionally or not, the two paintings were hung directly opposite each other in the Kunstverein, creating a contrast that undoubtedly played a role in the negative reception of Courbet’s work:

His “Artist’s Studio”, an enormous canvas, placed directly opposite Kaulbach’s “Nero”, includes a great number of capably painted figures but they leave us rather cold. It is impossible to speak of a composition in the real sense of the word. There is no real grouping, no real separation. Everything seems to have been positioned by chance. It would possibly make a stronger impression if its vis-à-vis did not automatically provoke a comparison.[40]

The German late-classicist was admired as a master of form, an elegant draughtsman, and virtuoso in composition; Courbet was accused of lacking precisely these qualities. In order to characterize the difference between the two artists, some critics used terms borrowed from the area of hygiene. Courbet was felt to be vulgar in comparison with the aesthetic “cleanness” of Kaulbach’s pictures. Emile Mario Bacano discovered the “filth of no less than twelve dusty weeks” in the Wrestlers, and he accused the female nude in the Studio of “not having washed for at least six months.”[41] Painting everything dirty was nothing less than an obsession and foul habit of the artist, the critic concluded. High and low seemed to clash at the Kunstverein. “From Kaulbach to Courbet! That is quite a leap: Almost as wide as from a mountain peak bathed in light to a gloomy, menacing abyss without a breath of air, without light and without life.”[42] The interpretation of the contrasting formal characteristics has been pushed even so far as to signify the difference between a German god and a French demon.[43]

The Viennese public was quite clearly not as “congenial” as Courbet had hoped. Critics seized upon his reputation calling him such things as pétroleur (incendiary), “painter of the Commune,” “hero of the Vendôme Column,” “son of the people at the barricades,” etc. As early as 1872, art historian Adolph Bayersdorfer warned the Viennese, in the Neue Freie Presse, of an upcoming sinister visit: “The bloody leader of the Communists Gustave Courbet—known since the days of the Commune as the chief of the naturalist movement in French painting—has decided to leave degenerate Paris, that incorrigible city of underlings, and move to Vienna, the new Babel that is so full of promise.”[44] In his polemical article Bayersdorfer relished in creating an image of Courbet as a person who—much to the horror of those living on the Ringstraße—would stir the fermenting elements of Socialism and have the Jesuit plague column on the Graben “vendômized.” Since his imprisonment in 1871, Courbet had repeatedly expressed his intention to move permanently to Vienna, notes Bayersdorfer who knew the artist in person.[45] However, the political situation was such that he never even made a brief visit to the “El Dorado on the Danube.”[46] During the Exposition, Adolf Thiers’s government collapsed and Courbet’s darkest fears became reality. On July 23, 1873, after being sentenced to pay almost 250,000 francs in damages for the Vendôme column, he crossed over the French border and entered into exile in Switzerland.

As shown in the company records, it was Paul Durand-Ruel who sent Courbet’s works to Vienna on February 22, 1873 and who received them all again on July 15, 1873. The paintings were part of a group of 59 works that the art dealer had taken into safekeeping from Courbet, probably to avoid their potential confiscation.[47] In his memoirs, Durand-Ruel recalls his disappointed hopes for the Vienna World Exposition: “I had every reason to expect a success. Unfortunately, my predictions were not confirmed. Cholera broke out in Vienna and this dealt the death blow to the Exposition. Everybody fled and I sold absolutely nothing.”[48] Only a few days after the opening of the Exposition, a stock-market crash put an abrupt end to the widespread feeling of optimism. Even Miethke complained that the enormous costs of “producing” Caterina Cornaro had hardly been covered. Courbet’s “guest performance” in Vienna turned out to be a failure as well, not only because he sold not a single painting, but more importantly because the exhibition with which he had intended to give an overview of his work remained an exposition incomplète. The critics positioned his fragmentary oeuvre in relation to other private ventures. There was talk of an unintentional rendezvous and three names were often singled out—each a program in itself, as the Fremden-Blatt noted: “Wilhelm Kaulbach the last survivor of the idealistic movement, Gustave Courbet at the absolute vanguard of French realism, and Hans Makart the most brilliant representative of the Viennese School.”[49] In the competition among these programmatic positions that took place outside of the World Exposition site, on the premises of the Kunstverein and the Künstlerhaus, Courbet was the one who definitely lost out. Whether the outcome would have been more favorable to Courbet in another context, and with different works, must remain subject to speculation.

[1] Gustave Courbet to Jules Castagnary, Ornans, February 9, 1873, in Letters of Gustave Courbet, ed. Petra ten-Doesschate Chu (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 481.

[2] Gustave Courbet to Jules Castagnary, Ornans, March 19, 1873, ibid., 493. For the political context see Jane Mayo Roos, “The Commune, the Column, and the Topping of Courbet,” in Early Impressionism and the French State (1866–1874) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 147–59.

[3] Gustave Courbet spoke frequently about his plans for an “exposition complète” in Vienna. See Patricia Mainardi, “L’exposition complète de Courbet,” in Courbet: artiste et promoteur de son oeuvre, ed. Jörg Zutter and Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, exh. cat. Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne; Nationalmuseum, Stockholm (Paris: Flammarion 1998), 101–57.

[4] Jutta Pemsel, Die Wiener Weltausstellung von 1873: Das gründerzeitliche Wien am Wendepunkt (Vienna and Cologne: Böhlau, 1989), 67.

[5] Andrea Meyer, “Rudolf von Eitelberger,” in Französische Kunst – Deutsche Perspektiven 1870–1945: Quellen und Kommentare zur Kunstkritik, ed. Andreas Holleczek and Andrea Meyer (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2003), 42.

[6] “Antonin Proust war ihm ebenso wichtig wie der Finanzminister, der die Milliarden zu beschaffen hatte. Es galt Frankreich, das nicht mehr an der Spitze der Politik marschierte, die Führung in der Kunst zu sichern.” Ludwig Hevesi, “Kunst und Budgetausschuss,” in Altkunst-Neukunst: Wien 1894–1908 (Vienna: Konegen, 1909), 290.

[7] “Il faut, à tout prix, exposer à Vienne. Ne pas se montrer à Paris, même en France, mais se faire voir à l’étranger, partout, telle doit être votre ligne de conduite.” Georges Riat, Gustave Courbet Peintre (Paris: H. Floury, 1906), 341.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Anne M. Wagner, “Courbet’s Landscapes and their Market,” Art History 4, no. 4 (December 1981): 415. In the years between his return from London after the turmoil of the Commune and the first Impressionist Exhibition in 1874, Paul Durand-Ruel also invested large sums of money in Edouard Manet and the young Impressionists.

[10] “Les affaires sont arrêtées uniquement par la crainte de retombe entre les mains des républicains et nous aspirons tous, et comme Français et comme commerçants, au rétablissement de la monarchie héréditaire qui seule peut mettre fin à nos maux.” “Monarchie ou Pètrole,” Le Figaro, October 31, 1873, 1.

[11] Cat. no. 472. Exposition Universelle de Vienne 1873: France: Oeuvres d’art et manufactures nationales, ed. Commissariat Général (Paris: Hôtel de Cluny, 1873), 130.

[12] “En effet, il s’y trouvait des œuvres capitales comme mon grand 'Sardanapale’ de Delacroix et beaucoup d’autres tableaux de nos plus grands maîtres, achetés par moi dans les dernières ventes, et d’autres toiles intéressantes, capables de donner une haute et juste idée de notre belle école française.” “Textes inédits des mémoires de Paul Durand-Ruel.” Durand-Ruel Archives, Paris. Neither this passage, nor the location of the gallery rented by Durand-Ruel in Vienna on Elisabethstraße (near the Künstlerhaus and the Academy of Fine Arts) appear in Lionello Venturi’s edited Durand-Ruel Mémoires in Archives de l’impressionisme (1939). My thanks to Flavie Durand-Ruel for this information, which she emailed to me January 18, 2011. In March 1873, Durand-Ruel had acquired the Death of Sardanapalus by Eugène Delacroix at the Hôtel Drouot for 96,000 Francs.

[13] Durand-Ruel shipped works to Vienna in several installments. According to a list preserved in the Durand-Ruel archive, Paris, the dealer sent off ten paintings on April 9, 1873, three of which were by Courbet: Boeufs au repos, Cours d’eau au milieu de roches, and Cutter en temps calme. My thanks to Flavie Durand-Ruel for this information, which she emailed me on May 14, 2012.

[14] “Ich glaube, dass dieser Fall wohl ein Unicum in der Geschichte des Wiener Bilderhandels bleiben wird.” Berta Zuckerkandl, “Aus dem Leben eines berühmten Kunsthändlers: Interview mit Herrn Miethke,” Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, January 29, 1905, 4.

[15] Gerbert Frodl, Hans Makart: Monographie und Werkverzeichnis (Salzburg: Residenz Verlag, 1974), 21. While the press reported a sum of 80,000 to 90,000 gulden, the dealer remembers a 50,000 gulden commission in his interview with Berta Zuckerkandl, “Aus dem Leben eines berühmten Kunsthändlers: Interview mit Herrn Miethke,” 4.

[16] “Die Kunsthandlung von Miethke und Wawra,” Kunstchronik, November 15, 1872, 78. According to Miethke the rent was 25,000 gulden. Zuckerkandl, “Aus dem Leben eines berühmten Kunsthändlers: Interview mit Herrn Miethke,” 4. See also Tobias G. Natter, Die Galerie Miethke: Eine Kunsthandlung im Zentrum der Moderne, Jewish Museum, Vienna, exh. cat. (Vienna: Jewish Musem, 2003),21–22.

[17] “Man entschloß sich jedoch, bei der in korrektem Vorgehen mit der genannten Firma de jure eingegangenen Pacht zu verharren.” August Schaeffer, “Karl Josef Wawra,” Neue Freie Presse, June 30, 1905, 2.

[18] “Die unglückliche Idee, das Bild in einer besonderen Bude im Prater zu zeigen, ist demnach als aufgegeben zu erachten.” “Die Kunsthandlung von Miethke und Wawra,” 78. For an excellent account of the touring single-picture show see Christian Torner, Ausstellungen einzelner Gemälde vom späten 18. bis zum Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte bürgerlicher Kunst, Kultur und Mentalität in Europa (PhD. diss., European University Institute, Florence, 1997).

[19] Chu, Letters of Gustave Courbet, 479.

[20] Torner, Ausstellungen einzelner Gemälde, 150.

[21] “Während diese alle Kräfte auf die Vorbereitung der Jahresausstellung im Künstlerhaus richtet, huldigt dagegen die Direction des Österr. Kunstvereins dem Grundsatze, monatlich frisch die Neugierde anzuregen und durch Außergewöhnliches und Seltenes, das schaulustige Publikum an sich zu locken. Befriedigt diese letztere Art die abwechslungssüchtige Menge, so bietet die erstere wieder den sich vertiefenden Kunstverständigen und mit Liebe zur Kunst sich Neigenden das Gewünschte.” Die Dioskuren: Deutsche Kunst-Zeitung 16, 1871, 28.

[22] Moritz Terke, director of the Kunstverein, to the Genossenschaft bildender Künstler, March 28, 1872, Künstlerhaus Archive, Vienna.

[23] Anselm Weissenhofer, “Der neuere Wiener Kunstverein,” Monatsblatt des Vereins für Geschichte der Stadt Wien 15, no. 1012(October-December 1929): 49–54. See also Emerich Ranzoni, Malerei in Wien mit einem Anhang über Plastik (Vienna: Lehmann & Wentzel, 1873), 94–112.

[24] Gustave Courbet to the director of the Österreichischer Kunstverein, Ornans, incomplete draft, in Chu, Letters of Gustave Courbet, 479.

[25] Gustave Courbet to Chérubino Pata, Ornans, Februray 26, 1873, ibid., 489.

[26] “Von den vierzehn Gemälden Courbet’s, welche ihrer Mehrzahl nach colossale Dimensionen haben, konnten der räumlichen Verhältnisse wegen vorläufig nur nachstehende aufgestellt werden: 'Das Atelier’, 'Die Ringkämpfer’, 'Ein armer Wohltäter’, 'Im Bade’, 'Selbstporträt des Künstlers’ und 'Porträt des Commune-Generals Cluseret’.” “Theater- und Kunstnachrichten,” Neue Freie Presse, April 26, 1873, 8. However, the total number of paintings submitted to the Kunstverein was eleven not fourteen. This number is given in most of the other newspaper reports and confirmed by new evidence discussed in footnote 47.

[27] The other five paintings were: A Burial at Ornans (1855, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), Young Ladies at the Banks of the Seine (1856-57, Petit Palais, Paris), The Death of the Hunted Stag (1867, Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie, Besançon), The Man with the Leather Belt (ca. 1845-46, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), and Madame Auguste Cuoq (ca. 1852-57, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

[28] “Es wäre für Wien, wo der Künstler zum ersten Male mit einer größeren Zahl von Werken auftrat, wichtig gewesen, eine Reihe von Arbeiten verschiedenen Genre’s aus verschiedenen Zeiten nebeneinander vorzuführen, um dem Urtheile des Publikums über den Werth Courbet’s als Maler eine breitere Basis zu geben; so aber wurde mit dem Grassesten begonnen, um vielleicht mit dem Besseren und Guten in echt kaufmännischer Weise erst später hervorzurücken.” “Aus dem Österreichischen Kunstverein (Schluß),” Kunstchronik, July 4, 1873, 604.

[29] “Kunstverein und Künstlerhaus (Kaulbach – Courbet – Makart),” Fremden-Blatt, May 14, 1873, 5.

[30] Carl Schuch to Karl Hagemeister, Paris, January 1883, in Karl Hagemeister, Carl Schuch: Sein Leben und seine Werke (Berlin: B. Cassirer, 1913), 128.

[31] “Il a sa date et son histoire en France; il faut qu’il reste ici . . . pour ne pas renouveler d’anciennes querelles.” Riat, Gustave Courbet, 341.

[32]“Sein 'Begräbnis in Ornans’ so wie sein 'Atelier’ bieten nur eine willkürliche Aneinanderreihung von Gestalten, welchen jeder psychologische Zusammenhang fehlt.” “Aus dem Österreichischen Kunstverein (Schluß),” 605.

[33] See for example Emil Ranzoni, “In der Kunsthalle,” Internationale Ausstellungs-Zeitung: Beilage der, Neuen Freien Presse, June 22, 1873.

[34] “'Der Arme Wohlthäter’, ein Bettler in Lebensgröße, welcher einem Zigeunerkinde Etwas schenkt, ist das Abschreckendste, Stümperhafteste, was seit lange gezeigt wurde.” Die Dioskuren: Deutsche Kunst-Zeitung 18, 1873, 151.

[35] “Der Künstler hat sich damit unbewußt selbst ironisiert und auch inzwischen durch die That bestätigt, daß sein Pinsel eben nicht für Menschendarstellung paßt, sondern nur in der Landschaft und im Thierstück gesunde Früchte erzeugen kann.” “Aus dem Österreichischen Kunstverein (Schluß),” 606.

[36] Sieghard Pohl, “Courbet und die Wiener Kritik 1873,” in Courbet und Deutschland, ed.Werner Hofmann and Klaus Herding, exh. cat. Hamburger Kunsthalle (Cologne: DuMont, 1978), 586–87.

[37] “Er schreit dafür zu laut - mit seiner Stimme, mit seinem Glaubensbekenntnisse, mit seinem Pinsel.” Emile Mario Bacano, “Kunstverein, II Courbet,” Tages-Presse, May 2, 1872, 3.

[38] “Der Staat giebt eben so wenig wie möglich Geld aus, und fast scheint es eine Verlegenheit, wenn irgend ein deutscher Künstler, getrieben von dem Drange, etwas im großen Stile zu arbeiten, was über das Maß der Vereins- und Handelsbilder hinausgeht, mit einem Werke historischen Stiles auftritt und Erfolg hat, was man bei der stetigen Ebbe des Kunstbudgets machen soll mit Werken, die schon ihrem Gegenstande nach das laute Geheimnis verrathen, daß sie gemalt sind ohne Auftrag, daß sie für keine staatlichen Bedürfnisse bestimmt sind, und daß der Staat—ungleich den französischen Nachbarn—so bedürfnislos in Sachen der Kunst, so bureaukratisch-haushälterisch ist, daß er weder bestellen kann, wie der französische, noch auch wollte, wenn er es könnte.“ Rudolf von Eitelberger, “Öffentliche Kunstpflege,” in Kunst und Kunstgewerbe auf der Wiener Weltausstellung 1873, ed. Carl von Lützow (Leipzig: Seemann, 1875), 273.

[39] “A qui donc M. Courbet destinait-il ce tableau? Où en trouverait-on la place? Ce n’est pas une église, à coup sûr, où il serait une insulte; ni dans une école, ni dans un hôtel de ville, ni dans un théâtre. Il n’y a qu’un grand seigneur avide de curiosités qui puisse songer à le recueillir dans son grenier; il se gardera de le placer dans son salon.” Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Du principe de l’art et de sa destination sociale (Paris: Garnier frères, 1865), 209.

[40] “Sein 'Atelier des Künstlers’, das dem Kaulbach’schen 'Nero’ gerade gegenüber hängt, eine riesige Leinwand, enthält eine reiche Zahl mitunter sehr tüchtig gemalter Gestalten, aber sie lassen uns ziemlich kühl. Von einer Komposition im höheren Sinne des Wortes ist nicht die Rede. Es gruppiert sich nichts und scheidet sich nichts. Alles steht, wie es der Zufall gestellt hat. Vielleicht würde es besser wirken, forderte sein vis-à-vis nicht so unwillkürlich zur Vergleichung heraus.” Friedrich Pernett, “Der Maler der Commune,” Morgen-Post, May 4, 1873, 2.

[41] “Daß es [the female nude in the Studio] ihren plumpen, mißgeborenen Leib seit mindestens sechs Monaten nicht gewaschen hat, wird man der Malweise Courbet’s, welcher alle seine Farben mit Roth mischt, begreiflich finden . . . ich will auch erst schweigen von dem Umstande, daß diese Ringer wiederum den ekelhaftesten Schmutz von mindestens zwölf staubigen Wochen an sich tragen.” Bacano, “Kunstverein, II Courbet,” 4. On the cleansing discourse in Viennese culture around 1900 see, for example, Anselm Wagner, “Otto Wagners Straßenkehrer: Zum Reinigungsdiskurs der modernen Stadtplanung,” bricolage: Innsbrucker Zeitschrift für europäische Ethnologie 6 (2010): 36–61.

[42] “Von Kaulbach auf Courbet! Es ist das ein weiter Sprung; fast so weit wie von einem lichtumflossenen Bergesgipfel in einen düsterdräuenden Abgrund ohne Luft, ohne Licht und ohne Leben.” Bacano, “Kunstverein, II Courbet,” 3.

[43] “Übrigens ist Kaulbach ein hehrer Gott gegen den Dämon Courbet, und Gott sei Dank ein Deutscher gegenüber dem Franzosen!”Die Dioskuren 18, 1873, 150.

[44] “Der blutige Kommunisten-Chef Gustave Courbet—von den Tagen der Kommune längst bekannt als das Oberhaupt der naturalistischen Richtung in der französischen Malerschule—hat sich entschlossen, das entartete Paris, diese unverbesserliche Unterthanenstadt, zu verlassen und nach Wien, dem hoffnungsvollen neuen Babel zu übersiedeln.” Adolph Bayersdorfer, “Gustave Courbet: Ein Steckbrief,” in Leben und Schriften, ed. Hans Mackowsky, August Pauly, and Wilhelm Weigand (Munich: F. Bruckmann, 1902), 121.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] This is mentioned in the so-called Bruillard, a book in which Paul Durand-Ruel recorded daily business operations. My thanks to Flavie Durand-Ruel for this information, which she emailed to me October 6, 2011.

[48] “J’avais tout lieu de compter sur un succès. Malheureusement mes prévisions ne furent pas confirmées. Le choléra se déclara à Vienne, ce qui porta un coup mortel à l’exposition en faisant fuir tout le monde et je ne vendis absolument rien.” Paul Durand-Ruel, “Mémoires de Paul Durand-Ruel,” in Les Archives de l’Impressionisme, ed. Lionello Venturi (Paris: Durand-Ruel, 1939), 199.

[49] “Wilhelm Kaulbach, der letzte Ausläufer der idealistischen Richtung, Gustave Courbet, die äußerste Spitze des französischen Realismus, und Hans Makart, den brillantesten Vertreter der koloristischen Schule.” Fremden-Blatt, May 14, 1873, 5.