The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master

Phillips Collection, Washington, DC

June 4–September 11, 2016

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

October 9, 2016–January 16, 2017

Ca’ Pesaro-Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna, Venice

February 11–May 28, 2017

Catalogue:

William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master.

Elsa Smithgall, Erica E. Hirshler, Katherine M. Bourguignon, John Davis, Giovanna Ginex, with a foreword by D. Frederick Baker.

Washington, DC.: The Phillips Collection in association with Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2016.

248 pp.; 176 color illus.; bibliography; checklist; and index.

$60.00 (hardcover U.S. edition)

ISBN: 9780300206265

William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master was an exhibition that celebrated Chase’s multiple artistic temporalities (fig. 1). The artist was a keen observer of contemporary art and life, he was deeply invested in the work of the Old Masters, and his innovative painting techniques strongly influenced several generations of art students who became modernist artists. With more than seventy works of art, the exhibition on view at the Phillips Collection from June 4 to September 11, 2016 reminded the viewer of the greatness of America’s unfairly forgotten master.[1] The exhibition argued a battery of points regarding Chase’s production in order to elevate his position in the canon of American art. Chase was an international figure who practiced multiple painting genres, who mastered oil painting and experimented with pastel, and who was involved in the art scene both teaching and promoting the work of others. Last but not least, he made beautiful paintings. The selection of works was spread out in the space and offered little explanatory text, thus emphasizing the pure enjoyment of their aesthetic qualities.[2] And it worked, because the ultimate success of the exhibition was the works themselves.

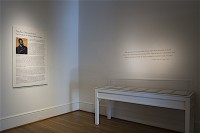

The first room of the exhibition provided an introduction to the show as well as to Chase’s biography (fig. 2). The wall label in this section highlighted Chase’s role as an “innovative painter” and “influential teacher.” Chase went to Germany at the age of 23 in order to pursue an artistic education. Both text and displayed works recorded his training years at the Munich Royal Academy of Art and the style practiced in this institution; bravura brushwork, dark tonal contrasts and painterly realism define the Munich style, evidenced in Chase’s paintings “Keying Up” The Court Jester (1875), The Turkish Page (Unexpected Intrusion) (1876), and Ready for the Ride (1877). The three works could not be more different in subject matter and execution, characterizing Chase’s work as eclectic from the very beginning.

“Keying Up” The Court Jester (1875), a painting of a German Renaissance subject depicted in a playful attitude, was submitted to the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia (48). The work constituted an exotic entry to the American art section of the world fair celebrating the centenary anniversary of the U.S. American independence; the painting earned Chase a medal. The Turkish Boy with Parrot portrayed an equally exotic theme, yet the varied chromaticity allowed for an enhanced perception of the masterly technique in rendering the different surfaces: there is the velvety sheen of the blanket, the furry quality of the cheetah carpet, the feathery softness of the parrot, the shiny reflections of the metal pieces and the wrinkly look of the boy’s bare soles (fig. 3). Closing the room’s selection is Ready for the Ride, a seventeenth century Dutch-style portrait of a contemporary woman readying to go riding (fig. 4). Surrounded by a petrol blue-colored wall, the selection of these three works testified to Chase’s multifaceted artistic production and set the tone for the show.

The second room reflected on Chase’s self-profiling as a cosmopolitan artist once he returned to New York City from Munich. Titled “Chase’s Rise in New York’s Tenth Street Studio (1878–1895),” this room rendered the artist in full bloom with three portraits and four studio scenes lit with natural light from a skylight, and enhanced with a much brighter blue color on the walls (fig. 5). This explosion of light and color spoke of Chase’s ambition, given that the first action of this artist was taking up a two-story studio and decorating it with “objects of wonder”: old furnishings, Asian fabrics, great copper vessels, lamps, exotic shoes, his own copies of masterpieces, and several hundreds of photographs of Old Master paintings (fig. 6) (18). As part of this eagerness to be professionally acknowledged, John Davis notes that Chase developed “a three-year campaign of submissions to the Paris Salon” (1881–83), culminating it with the Portrait of Dora Wheeler (fig. 7) (49–51).

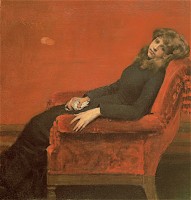

Dora Wheeler’s portrait is crucial for Chase’s project of self-fashioning both because of the sitter herself and as a work of art. Wheeler was Chase’s first private female student at a time when women artists did not have easy access to education.[3] By the time Chase painted the portrait, Dora Wheeler ran her own decorative firm partnering with her mother; the portrait’s background illustrates one of her designs (33). Chase’s investment in Dora Wheeler speaks of his willingness to include women in the artistic world as professionals in their own right. But the portrait touches on the artist’s models and strategic alliances too. Wheeler’s portrait clearly refers to James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s Portrait of the Artist’s Mother (1871), in which Whistler’s mother sits likewise in the center of the composition. With a subversive twist, Chase’s sitter is much younger, appears depicted with bright color combinations and stares defiantly at the viewer. Chase painted a pendant to Wheeler’s portrait with The Young Orphan, a work that flirts with a pastel red version of Whistler’s tonalist style (fig. 8). In the same exhibition room hung the portrait that Chase painted of Whistler himself when the former traveled to England in 1885 to meet the object of his admiration (fig. 9). After an initial period of friendship during which each artist painted each other’s portrait, Chase and Whistler parted with irreconcilable differences. The selection of works in this room could not better express Chase’s strategic moves to position himself in the avant-garde of American art, by both showing the artist’s self-fashioning and choice of professional coalitions, besides suggesting the size of his artistic ego.

The next section displayed Chase’s production of landscape painting in the 1880s (fig. 10). Bathed by the bright light reflected on the off-white walls, this room presented sixteen paintings under the title “Charting New Terrain: Chase as a Plein-Air Painter.” The title of this section was smartly chosen as the room emphasized how Chase dealt with new terrain in a geographic and thematic fashion as well as with the medium of pastels, which was new to him. In 1886, Chase likely attended the large exhibition of Impressionist art that the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel organized in New York. The exposure to Impressionism seemingly imprinted on Chase a way of looking that he materialized in impressionistic views of New York City (fig. 11). His fully lit cityscapes often presented dramatic compositions with perspectival rushes to the horizon executed with quick loose brushstrokes. This formal audacity corresponded with Chase’s choice of an American setting in the public parks of Brooklyn for his impressionist work painted en-plein-air. Barbara Dayer Gallati notes that the treatment of the setting was vague, however, lacking an explicit rendering of the urban scene and being almost emptied of human figures.[4] Indeed, a painting like A City Park evidences the abstract character of his cityscapes, removed from their physical and social urban context, and functioning purely as subjects for artistic experimentation.

Besides geographic preference, the intimacy of private scenes of daily life and the use of pastels constituted these innovations. Both The Open Air Breakfast and A Washing Day depict domestic activities taking place in Chase’s backyard. In the first case, Chase painted his wife, sister, and two daughters during breakfast time (fig. 12). The attention fell not on their figures, but on the seeming randomness of the composition capturing an uneventful moment of their lives. The latter picture renders a faceless figure in a sea of laundry lines and dispersed clothes that suggest a dancing quality (fig. 13). Impressionism inspired in Chase the locations, the compositions, and the subject matter as well as the medium. Chase started painting with pastel on paper in the early 1880s, producing works such as Young Girl on Ocean Steamer (1883), A Bit of Holland Meadows (1883) and The End of the Season (ca. 1884–85), all of them represented in the show.

Finally, the artist’s commitment to innovation in art took him to associate himself with the Society of American Artists (president 1880–81; 85–95), and to co-found the Society of American Painters in Pastel in 1883. The progressive character of these institutions and the novelties he introduced to his work hint at Chase’s modernity and at his avant-garde aspirations during the 1880s.

The key passage of the exhibition took place within the fourth section “At Home/At Play: Chase’s Interior World” (figs. 14, 15). This was the most ambitious section both in terms of the vastness of the exhibition space—with three full rooms—and in the quantity of works of art exhibited (more than twenty). It combined walls in off-white with the petrol blue color to display Chase’s production, capturing the female world in which he lived. His wife and daughters as well as his female students populated scenes that ultimately reflect on the art of painting itself. For instance, the painting Hall at Shinnecock, hanging next to the wall text, epitomized all these aspects (fig. 16). It renders Chase’s wife Alice Gerson and two of their daughters at their home at Shinnecock in a room full of works of art and exotic objects, such as the large Japanese vases. One of the little girls is observing a Japanese book on the floor, and in the mirror inserted in the closet right door the artist has painted his self-portrait. The clear reference to Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656) makes the work a statement not only about his cherished source of inspiration, but also about his domestic world functioning as a truly artistic sphere.

The rest of this room displayed other works that added to the poignancy of Hall at Shinnecock (fig. 17). In Tired, Chase painted a portrait of one of his young daughters where he explored the combination of pastel pink tonalities with dark brown applied in thick loose brushstrokes (fig. 18). In the Studio (Interior: Young Woman at a Table, 1892–93) captures Alice absorbed in the observation of a bound collection of prints. She stands not only in the interior of a room filled with art, but is also physically framed by several works. Finally, An Artist’s Wife is another witty exploration of the activity of art making and art appreciation (fig. 19). Alice sits in front of a painting and turns her head to the viewer as if suddenly disrupted from her absorptive observation of the work behind her. That work shows Alice in a landscape, playing with the theme of the picture within the picture by adding the same person in both. According to Nicolai Cikovsky, Chase was consciously trying to annul the boundaries between painting and the real world by challenging the distinction between art and actuality.[5]

This critical blurring of borders reappears in the next room within the same section, now devoted to female models posing with kimonos (figs. 20, 21, 22). Japanese art and culture fascinated Chase, who possessed Japanese books and vases, as well as kimonos, textiles and fans. In this series of works, Chase combined Japanese motifs and pictorial devices. For instance, the pastel Spring Flowers (Peonies) depicts a woman seated on a table and smelling the peonies arranged in a large vase (fig. 23). The woman is wearing a red kimono sprinkled with white decorations and is holding a Japanese fan. The white peonies, which mean good fortune and embody romance in Japanese culture, loom large in comparison to the woman’s face. Given the clear competition for attention between the flowers and the woman, Gallati reads the function of the figure as staffage, “yet another still-life component.”[6] Indeed, the same can be said of multiple female figures, who populate Chase’s works, posing with their heads turned away from the viewer (as in Washing Day), or revealing their face to the viewer but with a blurry quality. This is an aspect of his oeuvre that seemingly removes the vividness of their look (as in Hall at Shinnecock), but requires further research.

The opposite could be said of the female’s portraits that hang in the last room of the section “At Home/At Play: Chase’s Interior World,” where both his physical and spiritual daughters (his female pupils) appeared displayed in their own right (fig. 24). The portrait of Lydia Field Emmett, characterizes Chase’s attraction to “new women,” independent transgressive women perceived at the time as an American product (fig. 25). In a very compelling article within the exhibition catalog, Erica C. Hirshler argues that the way Chase expressed this fascination was both by making the women active participants in the painted scenes, and by posing them after male sitters’ postures captured by Old Master painters (25–27). An Artist’s Wife, disguised in seventeenth-century Dutch clothing and adopting the stance of Frans Hals’ Isaak Abrahamsz. Massa (1626) represents a clear example of his depictions of these bold women (fig. 19). The portrait of his former student Lydia Field Emmett constitutes another example. He portrayed her as a self-assured person who had become a successful society portrait painter.

The portraits and scenes of his daughters bring together Chase’s domestic world and artistic self-fashioning in an intriguing way. The works show either the sitters engaging in art appreciation or in children’s games. In Did you speak to me? (1897), one of his daughters suddenly turns around to the viewer as she was interrupted from observing a work of art, reminiscent of the portrait of Alice in An Artist’s Wife. The paintings of children in general could have functioned as what Emily Burns has termed a metaphor of freshness and renewal, as the figure of the child came to represent the notions of both “the modern” and the American nation in the late nineteenth century.[7] This body of work should also be seen connected to the period’s interest in the psyche and in a return to what Kathleen Pyne calls “a child’s way of seeing the world.”[8] The paintings Hide and Seek (1888), At Play (1895), and The Ring Toss (1896) represent children in their sphere of play, where the artist adopts their lower viewing perspective to physically participate in the ludic activities. Hide and Seek explores the element of mystery as the light filters through the curtain’s edge into the darkened room (fig. 26). In addition, the large scale of the glowing velvety chair appears uncanny in comparison to the girl’s size, reinforcing the notion that the image belongs to the children’s realm where mystery and wonder rule, and inspire the modern American artist.

The section “The View from Shinnecock Hills: Chase’s Mature Years” provided a refreshing view with summer landscape paintings executed en-plein-air displayed in a room with off-white walls (fig. 27). Chase and his family spent their summers at Shinnecock Hills from 1891 to 1902, where Chase directed the Shinnecock Summer School of Art and taught painting classes daily. The landscape paintings of this period have an added sophistication in terms of design that makes them especially compelling. The painting At the Seaside constitutes an exceptional case where Chase experimented with chromatic accents in bright red, yellow, and white to animate an horizontal composition (fig. 28). Idle Hours introduces a mass of grey clouds to the left, adding a dramatic atmospheric phenomenon that also destabilizes the composition with its asymmetric character (fig. 29). In The Big Bayberry Bush, a high horizon line creates room to depict Chase’s daughters’ playground: the surroundings of Chase’s home (fig. 30). All the landscape paintings that Chase created in this period and location contained references to his private life, with the presence of either his wife or his daughters or both, and with the depiction of the house or its immediate surroundings. Although all the landscape scenes look so bright, the visual associations with Chase’s private life and his explorations of weather conditions to create specific moods function as introspective explorations of the maturing artist.

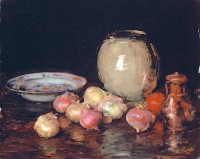

The final section of the show had a climatic effect with the display of Chase’s last self-portrait surrounded by the dark still lifes he painted in that period (fig. 31). With the title “Ambitious to the End: Chase’s Final Years at Home and Abroad,” and the accompanying wall text, the exhibition reminded the viewer of the fruitfulness of Chase’s later career. Chase received a gold medal at the Paris World Exhibition of 1900 and spent ten consecutive summers teaching art classes for Americans in European destinations. One of Chase’s fields of mastery, commonly used as demonstration pieces painted during the art classes for his students, were the still life paintings of seemingly ordinary things. In Just Onions (Onions; Still Life), he managed to create a fascinating composition that engages the rosy tones of the onions in a dialogue with the gray flower vase and copper vessel to the right (fig. 32). Still Life–Fish constitutes a great example of the fish paintings that brought Chase great renown (fig. 33). This exercise in textures, light, and color introduces again a note of uncanniness with the fish on the right disposed on the table as if caught swimming in the water. Moreover, the brown vase of the far left has a ghostly quality with the gleaming reflections of light as the only traces of its overall faded presence.

The Self-Portrait in 4th Avenue Studio encapsulated key ideas about the artist and his work, tying his private and public persona and bridging this last section of Chase’s exhibition with one site-specific show of his students’ work (fig. 34). Chase appears in a three-quarter portrait, standing in his studio in an aestheticist space. Attired in his well-known dandy style, he adopts a confident pose and defiant look. A large canvas divides the composition in two, separating Chase from the right side of the room. But the large canvas is off-center. It is his palette and brushes that take the center of the work as if making a statement about the physicality of his paintings, about the materiality of his works. Significantly, the canvas does not display a finished picture but loose almost chaotic strokes, advancing the daring abstract creations that his students would develop during the twentieth century. Indeed, Chase was a great master painter and a truly inspiring teacher as it is evidenced in the complementary section “Teacher Extraordinaire: The Students of William Merritt Chase,” where works by Georgia O’Keeffe, Edward Hopper, John Marin and Joseph Stella, all from the Phillips Collection, were on display (figs. 35, 36, 37). This last section managed to express the “individualistic ideals” that Chase encouraged his students to follow, with a representative selection of highly divergent styles and formats that embodied several strands of modernism. The message is clear: Chase was a modern master and strongly contributed to the development of an American modernism.

The excellent exhibition catalog provided several thematic essays that complemented an exhibition that was light in textual presence. Elsa Smithgall, the curator of the exhibition at the Phillips Collection, discussed Chase as a revolutionary figure in the early days of modern American art. Erica C. Hirshler, Croll Senior Curator of American Paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, reflected on Chase’s fascination for the “new woman,” and her representation through traditional Old Master style. Katherine Bourguignon, curator at the Terra Foundation for American Art, examined Chase’s role and performance as a teacher. John Davis, executed director for Europe and global academic programs, Terra Foundation for American Art, considered Chase’s work from an international perspective. Finally, Giovanna Ginex, independent curator for the Foundazione Musei Civici di Venezia, analyzed Chase’s relationship with Italy. Overall, the essays established the current state of the field in the study of Chase’s oeuvre, reviewed previous publications, and left room for further exploration.

William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master constituted a successful selection of Chase’s masterpieces to connect the viewer with his artistic production. The works represented Chase’s multiple sources, interests, and styles, in addition to his artistic exploration with media and radical pictorial devices. The show addressed many themes regarding Chase’s art: the artist’s studio and self-fashioning, artistic rivalry, the domestic world, the new woman, children’s play, Japonism and Orientalism in general, the Old Master tradition, and reflections on art making. Some other aspects that a close look at the works revealed were the shared uncanny quality of oversized, glowing objects (a certain material agency), the almost exclusive use of females as models and their frequent appearance as staffage (with the lack of agency that it denotes). What the exhibition managed to clearly convey was the potentiality of Chase’s painted work, the richness of this corpus of a modern American artist in want of deeper engagement. The show should therefore be celebrated as a milestone in the historiography of the scholarship on Chase’s work, and the springboard from which future studies will develop critical reflections on the master’s legacy.

Alba Campo Rosillo

PhD Student, Art History Department, University of Delaware

cmprsll[at]udel.edu

I am greatly indebted to Curator Elsa Smithgall and to Media Relations Manager Sarah Corley from The Phillips Collection for their help and support.

[1] The previous major retrospective of William Merritt Chase’s work took place in 1983, and was organized by Ronald Pisano. See Ronald G. Pisano, A Leading Spirit In American Art: William Merritt Chase, 1849–1916 (Seattle: Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, 1983).

[2] In an exchange of personal correspondence, Curator Elsa Smithgall from The Phillips Collection stated that the selection of the works was based on the “highest quality masterworks” of the artist. Elsa Smithgall, e-mail message to author, November 8, 2016.

[3] Bruce Weber notes that William Morris Hunt broke ground in 1860s Boston accepting female artists for private training, and that Chase was praised for his action. Wheeler studied with Chase from 1879 until 1881. See Bruce Weber, “Chase Inside and Out: The Aesthetic Interiors of William Merritt Chase,” Chase Inside And Out: The Aesthetic Interiors Of William Merritt Chase, exh. cat. (New York: Berry-Hill Galleries, 2004), 32.

[4] Barbara Dayer Gallati, William Merritt Chase (New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1995), 71.

[5] Nicolai Cikovsky Jr. “Interiors and Interiority.” William Merritt Chase: Summers At Shinnecock 1891–1902, D. Scott Atkinson and Nicolai Cikovsky Jr. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1987), 58–59.

[6] Gallati, William Merritt Chase, 116.

[7] Emily C. Burns, “Innocence abroad: the construction and marketing of an American artistic identity in Paris, 1880–1910” (PhD dissertation, Washington University, 2012), 205.

[8] Kathleen A. Pyne, “Response: On Feminine Phantoms: Mother, Child, and Woman-Child,” The Art Bulletin 88, no. 1 (March 2006): 44. Pyne has expanded her thinking on the topic in the manuscript Modernism and The Feminine Voice: O’Keeffe and the Women of The Stieglitz Circle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).