The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Fantin-Latour: À Fleur de peau

Musée du Luxembourg

September 14, 2016 – February 12, 2017

Musée de Grenoble

March 18 – June 18, 2017

Catalogue:

Laure Dalon, director, with contributions by Xavier Rey, Valérie Lagier, Bridget Alsdorf, Laurent Salomé, and Leïla Jarbouai,

Fantin-Latour: À fleur de peau.

Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2016.

256 pp.; 210 color illustrations; bibliography; checklist; chronology; bibliography.

35€ (hardcover)

ISBN: 078-27118-6348-8

“The works of Henri Fantin-Latour are unclassifiable” (11). This succinct statement, which opens the preface to the catalogue for the exhibition Fantin-Latour: À Fleur de peau, stands as the undivided verdict in nearly all critical studies that have contended with the artist’s nebulous historiographical position. According to the curators Laure Dalon, Xavier Rey, and Guy Tossatto, the dearth of serious scholarship and attention accorded to Fantin-Latour (1836–1904) is directly attributed to his independence from the major artistic movements of his time. In truth, although he fiercely renounced any affiliation with any specific school, he was certainly not uninvolved. At the end of the 1850s, he had dabbled in Gustave Courbet’s brand of Realism but was disillusioned with its precepts by the early 1860s. During the uproar of Impressionism, he befriended its leading exponents but deemed their en-plein-air methods “atrocious” and their brushwork “slack.”[1] Finally, as he approached his twilight years, he increasingly evoked the formal abstraction of music in a pictorial language that anticipated fin-de-siècle Symbolism, an association he would reject along with invitations to Joséphin Péladan’s infamous Rose + Croix soirées.[2] Furthermore, his ambitious quartet of group portraits—Homage to Delacroix, A Studio at Batignolles, The Corner of the Table, and Around the Piano—testify to his engagement with his contemporaries. Above all, Fantin’s situation within the standard art historical periodization is compounded by another contradiction: the dialectical tension between his allegiance to objective reality and his irrepressible longing for pure fantasy.

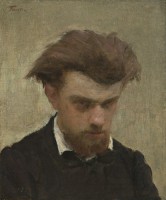

Better known for the verisimilitude of his bountiful still-lifes and the documentary value of his monumental group portraits, Fantin’s genre of artworks inspired by allegory, myth, and music have largely been overshadowed. From the enigmatic expression of the visage that graces the publicity poster (fig. 1) to the evocative title of the exhibition, Fantin-Latour: À fleur de peau clearly aspires to illuminate the more poetic vein in the artist’s enterprise. This was likewise the direction of the retrospective De la Réalité au rêve held in 2007 at the Fondation de l’Hermitage in Lausanne.[3] Referring to this earlier endeavor, Rey, in his introductory essay, reiterates the artist’s career path as “a trajectory from reality to dream . . . a gradual emancipation from what can be regarded as tradition and the real” (19). The current exhibition, previously on view at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris and now showing at the Musée de Grenoble, proposes that Fantin’s latent Romanticism and nascent Symbolist aesthetics were present from the very outset of his “journey” (20). As implied by the richly suggestive title, the idiomatic translation of à fleur de peau denotes a heightened sensibility which in its literal sense, means skin deep.[4] Paradoxically, the phrase alludes to what is not immediately visible, to what mysteriously quivers beneath the outer surface. This elusive facet of Fantin’s persona and art anchors the overarching narrative of the exhibition: “In every case, here is an intense and delicate artist, who conceals a highly sensitive sensibility under an austere gaze.”[5]

Organized chronologically and spread across five themed galleries at the Musée du Luxembourg, À Fleur de peau presented a panorama of nearly 180 drawings, paintings, and pastels spanning the artist’s career. A large photographic reproduction capturing a middle-aged artist in his studio welcomed visitors at the entrance (fig. 2). The duality that underpinned Fantin’s artistic inclinations might have been more effectively announced had an alternative photo from the catalogue been used instead (24). In the latter option, Fantin is visually framed by a lithographic stone bearing an impression of To Rossini in the foreground and the looming presence of The Reader in the background. Atmospherically lit and painted in sumptuous shades of plum and Venetian red, the first gallery was dedicated to the theme “Espérance et courage (1854–1873)” [Hope and Courage (1854–1873)]. Upon entering the narrow space, a series of brooding self-portraits on the right wall and a trio of melancholic portraits depicting his sisters on the left wall acted as a structural axis that directed the viewer’s attention to Fantin’s confident gaze in his Self-portrait Seated at Easel (1858, Nationalgalerie, Berlin) (figs. 3, 4). The haunting intensity, darkened totalities and agitated brushwork exemplified by the smaller self-portraits exuded a palpable feeling of unease while the somber stillness that lingers in the paintings of his sisters emitted a quiet sense of resignation.

The touch of tristesse that suffused the first section of the gallery mirrored Fantin’s profound depression, which persisted from the time he withdrew from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1854 to the early 1860s. The correspondence dating from this period is replete with regrets, self-doubt, and aesthetic debates. In 1859, all three of his submissions to the annual Salon were rejected, one of which depicted his schizophrenic sister Nathalie who would begin her lifelong confinement at the asylum the same year. In the following decade, Fantin took on the financial burden of providing for his immediate family, the payment of Nathalie’s institutionalization fees, and the procurement of clients for his father, who was a portrait painter. Moreover, his depression was exacerbated by a restless sense of ennui that besets any young man who has yet to leave the parental home. The background on the artist’s fragile state of mind only appeared midway into the gallery where a truncated version of Laure Dalon’s essay “La Peinture est mon seul plaisir, mon seul but” (Painting is my only joy, my only goal) was displayed as a didactic wall panel. The title is excerpted from a letter written by Fantin and was used as the subtitle for the thematic heading on the central wall; each succeeding gallery adopted the same format. Despite the inclusion of another quote in which Fantin lamented his “tormented existence” and “pitiful soul,” the causes of his anxiety likely remained obscure to viewers due to the brevity of the text.

Within the context of the “Hope and Courage” theme, James McNeill Whistler’s role in uplifting Fantin’s spirits and Edwin Edwards’ instrumental part in promoting his reputation as the still-life painter du jour in Britain merited a more thorough account in the wall texts. The remainder of the gallery was devoted to Fantin’s still-lifes depicting splendid bouquets and luscious fruits alongside portraits of his future wife and sister-in-law: Victoria and Charlotte Dubourg (fig. 5). Concerning the principal narrative of the exhibition, the interweaving of Fantin’s moody portraits throughout the space reminded viewers of the Romantic undercurrent of his temperament and art (fig. 6). In fact, the placement of the artist’s very first imaginative painting, The Dream (1854, Musée de Grenoble) in a dark and unassuming corner to the right of the entrance underscored these lesser-known aspects of his work (fig. 7). This visionary scene depicts an encounter between a winged Prud’honesque figure and a slumberous nude in an Arcadian landscape. At this incipient point of what Fantin would later describe as his “projets d’imagination” (imaginative projects) the isolation of The Dream was suitable and the incongruity of its subject matter revealing.[6]

Before exiting this gallery, the viewer came vis-à-vis with Fantin’s Self-Portrait (1859, Musée de Grenoble) (fig. 8). This painting visually harmonized with two works in the adjacent room: the Homage to Delacroix (1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and his Portrait of Fantin (1861, Musée de Grenoble) (fig. 9). The juxtaposition of these three images prompted the audience to relate the figure of Fantin (in his ivory white blouson) to the one portrayed in the Homage and to the preparatory conté portrait used for the latter. Altogether, these works subtly illustrated his growing ambitions. As with the other group portraits featured in the exhibition, a diagram identified the sitters on a didactic panel next to the Homage. The content of the text, extracted from Rey’s notes in the catalogue, fell considerably short of providing an adequate account of the painting’s significance. Fantin debuted his commemorative painting at the Salon of 1864. The critical reception was uniformly negative. Reviewers disapproved of the humdrum interior setting, challenged the structural hierarchy of the sitters, reproached the inclusion of inconnus (unknown figures), and sneered at the mishmash of catatonic faces. Moreover, critics were confounded by the intrusive presence of Champfleury and Edmond Duranty—the apostle of Realism and his disciples—in a work that implicitly proclaimed an allegiance to Romanticism as embodied by Eugène Delacroix and Charles Baudelaire. Blistering diatribes in the press attested to the bafflement that this ideological confrontation provoked. Beyond the acknowledgment of the obvious tension in the Homage’s program, the didactic panel provided limited insight on Fantin’s veneration of the Romantic icon.

Also problematic was the location of the wall announcing the theme “Ambitions et Innovations (1864–1872)” [Ambitions and Innovations (1864–1872)] in the adjacent room which was painted in red (fig. 10). This disjunction visually separated the Homage from the Studio at Batignolles (1870, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), Corner of the Table (1870, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), and the surviving sketches for the failed Toast! (figs. 10, 11). The intention behind this design decision might have been to differentiate the Romantic icon in the Homage from the forerunners of Modernism in the later portraits. Altogether, these ambitious works, the crown jewels of the Musée d’Orsay’s collections, inexorably linked the artist with the artistic collectives he portrayed and in turn, the aesthetics they exemplified. Hence, although Fantin was not directly involved with the Impressionist and Symbolist schools, his name was associated with Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine, to name a few. While the didactic panels generally addressed the theme, the complex nature of the group portraits were left to the catalogue (fig. 12). Viewers would have gained a deeper understanding of Fantin’s modernity had excerpts from Bridget Alsdorf’s illuminating essay, “Shoulder to Shoulder: At the Corner of the Table” been included. The psychological distance and lack of physical interaction between the sitters in Fantin’s group portraiture, she argues, were symptomatic of the “impossible coexistence” between the artist’s need to assert his individuality and the obligation to demonstrate group solidarity (33). On this note, the informational panel for At the Corner of the Table did not attempt to clarify why the face of the politician Camille Pellatan was chosen to grace the Musée du Luxembourg’s official exhibition poster. Beyond his attractive features and penetrating glare, attributes found in Fantin’s strikingly similar self-portrait of 1861, the rationale behind Pellatan’s prominence mystifies (fig. 13).

The following gallery, “Nature et vérité (1873–1890)” [Nature and Truth (1873–1890)] showcased Fantin’s mature still-lifes and portraits. The two partitioned rooms that comprised the gallery were painted in deep purple. The first section, “Poésie de l’intime, les ‘études d’après nature’” (“The Poetry of Intimacy, ‘Studies after Nature’”) opened with an opulent display of the artist’s most virtuosic flowers and fruits. Under the dramatic lighting, which at times was too dim, the still-lifes appeared to bloom in a setting that evoked a nocturnal garden (fig. 14). The next room presented an impressive lineup of the artist’s family members and friends. Among the highlights were the Portrait of Charlotte Dubourg (1882, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and Reading (1877, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon) (fig. 15). This pairing, by virtue of the physical proximity of the individual works and the relationship between the two sitters, conveyed an intimacy despite the pervading sense of psychological detachment. Fantin’s imposing Portrait of Edwin and Ruth Edwards (1875, Tate Gallery, London) introduced the next theme: “Famille, amis, mécènes” (“Family, Friends, Patrons”) (fig. 16). Aside from their role as Fantin’s dealers, the Edwards obligingly indulged the artist’s fondness for music with his favorite renditions of Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven during his stays in Sunbury. The couple even transcribed a piano and violin duet by Schumann for flute and piano to please Fantin. This moment was captured in the drawing A Piece by Schumann (1864, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), which was displayed in the last gallery. Ruth happily reminisced about their musical soirées in the correspondence for decades. Edwin, an amateur etcher, shared his technical expertise with Fantin. The couple’s importance in Fantin’s life merited a longer explanatory note in the didactic panels. Likewise, the majestic Portrait of Adolphe Jullien (1887, Musée d’Orsay) called for a more in depth look, considering the pre-eminent musicologist and highly respected writer for the Revue et gazette musicale provided Fantin with musical education to envy (fig. 17). He would subsequently commission the artist to illustrate his two acclaimed monographs on Wagner and Berlioz.[7] In return, he wrote the artist’s first biography.[8]

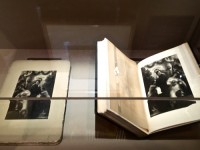

The penultimate gallery consisted of two opposite-facing rooms that distinctly stood apart from their boldly colored surroundings in a shade of unobtrusive beige. The lack of visual allure may be attributed in part to the prosaic implications of the gallery’s theme: “Fantin au travail” (“Fantin at Work”). The first room, “D’après le nu” (“After the Nude”) focused on Fantin and photography. As repeated in the exhibition catalogue, press release, and program notes, one of the most innovative aspects À Fleur de peau brings to the scholarship is the light it sheds on the vital role of nude photography in the artist’s creative process. Collectively, the brief but insightful essays written for this section of the exhibition constitute the most extensive exploration of the subject in the literature. During his lifetime, Fantin amassed an astonishing collection of over 4500 prints. Although Fantin’s widow bequeathed the photographs to the Musée de Grenoble in 1921, the artist himself stipulated that these were not to be revealed until 1936, the centenary of his birth (167). Two-thirds of the photographic archives are reproductions of famous masterpieces while the remaining third comprises of females nudes in cliché poses drawn from the sanctified galleries of the Salon.

Only the nudes were included in the exhibition at the Musée du Luxembourg because these were often directly transposed and transformed into languorous nymphs and muses by Fantin for his imaginative compositions. A large assemblage of photographs was displayed on the wall to the right of the entrance and a group of related chalk drawings to the left (figs. 18, 19). A horizontal glass vitrine faced the viewer and showcased individual prints as well as those compiled by Fantin in numerous scrapbooks (fig. 20). To illustrate the direct influence of nude photography on his imaginative genre, the paintings By the Seaside (1903, Musée d’Art et Industrie, Roubaix) and The Awakening (1904, Musée d’Art et Industrie, Roubaix) were positioned above the vitrine (fig. 21). The inclusion of Fantin’s Self-portrait (1885, Istituti museali del Polo Museale, Florence), which shows a pair of discernibly furrowed brows, a slight scowl and a severe black jacket, hinted at the artist’s prudish nature, one which would have benefited from the substitution of photography for real models (174).

The space directly across from this room was entirely dedicated to the genesis of Fantin’s Commemoration (1876, Musée de Grenoble) (fig. 22). The monumental painting occupied an entire wall. On one side, a trio of preliminary lithographs documented the multiple stages of development involved in Fantin’s creative process. Opposite this wall, a glass case displayed the lithographic stone on which he sketched a minor variation of the Commemoration for use as the frontispiece in Jullien’s monograph on Berlioz; this iteration was subsequently renamed The Apotheosis (1888, Musée de Grenoble) (fig. 23). In light of Fantin’s eventual fame as the lithographer par excellence of his generation, viewers might have benefited from an explanatory note on the differences between the transfer paper method of lithography versus the sur pierre (directly on the stone) approach. Nearly all of Fantin’s prints belong to the first category because the delicacy of papier végétal and the softness of the lithographic crayon were ideal for the execution of his gauzy and vaporous pictorial effects. A closer analysis of the inventive techniques Fantin employed to achieve his distinct facture would have also underscored his catalytic role in the revival of lithography.

The idea for the piece was conceived after a performance of Berlioz’s Romeo and Juliet at the Théâtre du Châtelet on December 5, 1875. Ostensibly, the symphonie dramatique had left such a profound impression on Fantin that ten days later, he was at work on his first painted pochade (sketch). Above all, the performance impelled him to re-evaluate the French composer’s position in his musical pantheon: “Berlioz,” he proclaimed was “the first to fuse drama, the modern poetic, with Music.”[9] The expansive iconographic program and the fact that Fantin regarded The Commemoration to be his “first real painting” confirm its significance. His idolization of the composer is also evidenced by his own presence in the painting. The only other example where he appears alongside one of his heroes is in the Homage to Delacroix. In his view, “He [Berlioz] is actually the first to create a Romantic art that corresponds so well to that of Delacroix’s own.”[10] Unfortunately, the watered down information on the didactic panels offered only the slightest glimpse into the work’s fascinating history. The most important, albeit obvious insight that the text did manage to articulate, centered on Fantin’s literal embodiment amidst the cast of dramatis personae in the painting: The Commemoration represented for the first time the synthesis between reality and fantasy. Fantin, seen from behind, is situated at the border of the composition, poised between the threshold of two disparate realms. This image thus set the stage for the final gallery: “Féeries” (“Enchantments”) (1854–1904).

The last gallery was the largest and most visually impressive room in the exhibition at the Musée du Luxembourg. The walls continued the rich plum color from before and the space was saturated in shadow and accented with bluish purple spotlights (fig. 24). Overall, the atmosphere pulsated with a drama that perfectly complemented the theatricality of Fantin’s luminous operatic visions and lavish allegorical fantasies (fig. 25). The introductory text on the central wall brought the viewer back to the The Dream of 1854 by summing up how Fantin’s faithfulness to nature impeded the full expression of his Romantic inclinations. Known to his friends and journalists as a peintre-mélomane (music-loving painter), his love of music was first ignited by his affinity for Robert Schumann whose difficult personal life he identified with. Two walls displayed works inspired by Schumann: the chalk drawing A Piece by Schumann (1864, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and the lithograph The Final Theme of R. Schumann (1895, Musée de Grenoble). The second image is a reworking of a painted sketch from 1874, which was intended to be a full scale homage to Schumann. This project was never realized due to the death of Fantin’s father. He subsequently turned his attention to The Commemoration. This sequence of events is somewhat articulated by the carefully considered placement of The Final Theme of R. Schumann on a wall with a large opening through which the Berlioz tribute can clearly be seen (fig. 26).

Richard Wagner completed Fantin’s revered trinity of musical greats and, as with Schumann and Berlioz, he exalted the German maestro as the embodiment of “la musique de l’avenir” (the music of the future).[11] Correspondingly, the preponderance of musical oeuvres in the final gallery were adaptations from Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung, Lohengrin, Parsifal, and The Master Singers of Nuremberg: a score of lushly evocative images that are best appreciated as transpositions of mood rather than transcriptions of the libretti (fig. 27). Thoughtful pairings between Fantin’s lithographs or drawings and their reinventions in oils and pastels allowed audiences to note the distinct facture which he consistently applied across all media to lend a diaphanous, ethereal quality to his enveloppe. Two such groupings included the sketch and painted versions of Prelude to Lohengrin (1892, Musée de Grenoble; 1892, private collection) and the lithographic and painted versions of the Finale of the Valkyrie (1877, Musée Fabre, Montpellier; 1879, Musée de Grenoble, Grenoble) (figs. 28, 29).

The information on the wall that signaled Wagner’s influence on Fantin’s imaginative genre was surprisingly limited, considering the seismic effect of The Ring cycle on the actualization of the artist’s musical-visual aesthetic. In 1876, Fantin postponed his marriage in order to travel to Bayreuth for the third performance of the epic tetralogy. There, he would feel the full force of Wagner’s acoustic, musical and scenic innovations. Upon his return to Paris, he inaugurated his own cycle of lithographs inspired by the Ring, beginning with The Rheinmaidens: a favourite scene, which he would reinvent in oil and pastel (fig. 30). Victoria Dubourg’s Catalogue de l’œuvre complet indicates that during the 1870s–1880s, Fantin’s lithographic output outnumbered his works in all other media, an unusual direction given his ambition to succeed in the Salons where grande machine paintings were more reliable vehicles to fame.[12] The prolific number of lithographs he executed after Bayreuth affirms the tremendous impact of Wagner’s opera on his creativity.

Accordingly, the artist’s final group portrait, Around the Piano (1885, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) visually anchored the gallery by virtue of its size and program. The image depicts several members from Le Petit Bayreuth: the Parisian fan club for Wagner’s most ardent and erudite acolytes. Seated around the well-known composer and Wagner disciple Emmanuel Chabrier are Camille Benoît, Amédée Pigeon, and Adolphe Jullien who indefatigably championed the works of the composer even in the midst of the Germanophobic climate generated by the Franco-Prussian war. Fantin was one of the privileged attendees and relished the musical soirées, which featured piano transcriptions and orchestral arrangements of Wagner’s operas and pieces by other vanguard German composers. In contrast to Rey’s conclusion in his notes to Around the Piano, the Wagnerian agenda is difficult to overlook, even if the score on the piano may be Brahms (224). Fantin’s affiliation with Le Petit Bayreuth and contributions to the Revue Wagnérienne would unavoidably lead to an unwilling association with the Symbolists

As the first retrospective held in Paris since the major exhibition jointly organized by the National Gallery of Canada, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and the Réunion des Musées Nationaux in 1982, Fantin-Latour: À Fleur de Peau at the Musée du Luxembourg sought not only to present the most comprehensive collection of Fantin’s oeuvres to date, but also to illuminate new aspects of his creative process and identity. With its atmospheric lighting, sumptuous color scheme, and dynamic vistas created by numerous partitions with slits and openings, the exhibition succeeded in enhancing the artworks and enchanting its audience. Rarely have Fantin’s prolific blooms appeared so radiant and his fantastical reveries as intangible as music itself. The scope of the exhibition, with the occasional aid of the didactic panels, also enabled viewers to discern Fantin’s engagement with contemporaneous artistic developments such as Realism and Parnassian poetics as well as influences from the past. Ultimately, the overarching objective of the exhibition—that is, to unveil the simultaneous duality between reality and fantasy in Fantin’s art—was only vaguely realized. Notably, it was not until 1887, when Gustave Tempelaere became his exclusive art dealer, that Fantin would rejoice in the complete freedom to paint his “projets d’imagination.” Under Tempelaere’s auspices, full-scale oil paintings and pastels illustrating musical, allegorical, and mythical themes became a staple in Fantin’s repertoire. The artist plunged headlong into the “genre féerique” (enchanting genre) and by the 1890s, all his Salon submissions were imaginative pieces.[13] All in all, À Fleur de peau is another variation on the réalité au rêve (reality to dream) theme. The trajectory from one realm to another, from the grounded to flights of fancy is simply too well defined to be seen in any other way. To quote the artist himself: “I began by copying the great masters, then nature. I have been painting my dreams for a few years now. I have slowly moved from reality to dream. This voyage has lasted almost my whole life.”[14]

Corrinne Chong, PhD

Independent scholar

corrinnecareens[at]gmail.com

Unless otherwise noted, all English translations are the author’s own.

[1] Letter from Henri Fantin-Latour to Otto Scholderer, April 16, 1874, in Correspondance entre Henri Fantin-Latour et Otto Scholderer (1858–1902), edited by Thomas W. Gaehtgens, Mathilde Arnoux, and Anne Tempelaere-Panzni (Paris: Éditions de la maison des sciences de l’homme, 2011), 212.

[2] Douglas Druick and Michael Hoog, Fantin-Latour, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1982), 343.

[3] Juliane Cosandier, Rudolf Koella, Nadia Schneider, et al., Fantin-Latour, de la réalité au rêve, exh.cat, (Lausanne: La Fondation de l’Hermitage, 2007).

[4] I would like to thank Professor Peter Dayan from the University of Edinburgh for clarification on the expression à fleur de peau.

[5] This quote appears in the press release and on the text panel of the entrance wall: “Dans tous les cas, un artiste intense et délicat cachant sous les glacis d’une peinture austère une sensibilité à fleur de peau.”

[6] Letter from Henri Fantin-Latour to Otto Scholderer, March 10, 1873, in Correspondance entre Henri Fantin-Latour et Otto Scholderer, 196.

[7] Adolphe Jullien, Richard Wagner sa vie et ses oeuvres; ouvrage orné de quatorze lithographies originales par M. Fantin-Latour (Paris: J. Rouam, 1886); Berlioz, sa vie et ses oeuvres; ouvrage orné de quatorze lithographies originales par M. Fantin-Latour (Paris: Librairie de l’art, 1888).

[8] Adolphe Jullien, Fantin-Latour, sa vie et ses amitiés; lettres inédites et souvenirs personnels, avec cinquante-trois reproductions d’œuvres du maitre, tirées à part, six autographes et vingt-deux illustrations dans le texte (Paris: L. Laveur, 1909).

[9] Letter from Henri Fantin-Latour to Otto Scholderer, February 9, 1876, in Correspondance entre Henri Fantin-Latour et Otto Scholderer, 242.

[10] Letter from Henri Fantin-Latour to Otto Scholderer, April 14, 1877, in ibid., 262.

[11] Letter from Henri Fantin-Latour to his parents, August 23, 1864, in Henri Fantin-Latour, Copies de lettres de Fantin à ses parents et amis par Victoria Fantin-Latour, 4 fasc. (Grenoble: Manuscrits de la Bibliothèque Municipale de Grenoble) R.8867, Cahier I.

[12] Victoria (Dubourg) Fantin-Latour, Catalogue de l’œuvre complet (1849–1904) de Fantin-Latour établi et rédigé par Madame Fantin-Latour (New York: Da Capo Press: 1969, unchanged reprint of the 1911 Paris edition).

[13] Arsène Alexandre, “Fantin-Latour,” Le Monde moderne, December 1895, 836.

[14] The original quote in French is as follows: “J’ai commencé par copier les maîtres, puis la vie. Depuis quelques années je peins mes songes. Je suis arrivé lentement de la réalité au rêve. Ce voyage a presque duré ma vie.” See Jerôme Tharaud, “Visites d’ateliers: Chez M. Fantin-Latour,” Journal des débats, June 12, 1904.