The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Carrier-Belleuse, Le maître de Rodin

Palais de Compiègne, Compiègne, France

May 22 – October 27, 2014

Catalogue:

Carrier-Belleuse, Le maître de Rodin.

June Hargrove and Gilles Grandjean.

Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2014.

192 pp.; 180 color illus.; checklist; bibliography; index.

€ 35.00

ISBN: 978-2-7118-6158-3

A sculpted figure of a shapely young woman, intoxicated by the fruits of Bacchus, flirts with a bust of a god on a herm. She locks eyes with the ancient-styled sculpture, but the head of the god, who may be Bacchus or Hermes, seems alive, and he smiles ever so suggestively in response to her supple form. Everything soars and falls in sensuous curves: the tendrils of ivy; the long tresses of the bacchante floating in the breeze; her slender arms that encircle and decorate the god’s head with succulent grapes; her robe, gingerly clipped to her small waist with a delicate belt and clasp. In 1863, when the work was shown in the Paris Salon of that year, the critic Paul Mantz saw in this sculpture what anyone today would also recognize: “M. Carrier has the sense of life” (39).

The “M. Carrier” who sculpted this Bacchante (fig. 1) was the artist better known today as Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse (1824–1887), whose life and works were the subject of a significant retrospective exhibition recently held at the Palais de Compiègne and organized by the Réunion des Musées Nationaux Grand Palais and the Palais de Compiègne, with support from the Musée d’Orsay. Those of us who know Carrier-Belleuse’s torchères of the grand staircase at the Opera Garnier in Paris have waited a very long time for this show; according to the list of exhibitions in the accompanying catalogue, there has never before been a retrospective devoted solely to Carrier-Belleuse’s sculptures and objets d’arts. In the summer of 2011, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs presented a small show of his drawings, without a catalogue, and his works have been placed in quite a few exhibitions (I counted forty); here in a Second Empire show, there in a Sèvres show. Most often Carrier-Belleuese’s works have been included in presentations that were actually focused on his famous assistant, Auguste Rodin.

Here the tables were turned. Carrier-Belleuse, Le maître de Rodin was an exhibition with two goals: firstly, it presented the first proper retrospective of Carrier-Belleuse and worked to position him as one of the most important and prolific sculptors and decorative artists of the second half of the nineteenth century. Secondly, the exhibition served to illustrate the connections and collaboration between the artist and his assistant Rodin, especially in the years between 1863, when Rodin entered Carrier-Belleuse’s atelier, and 1886, a year before his master’s death. The importance of Carrier-Belleuse to Rodin’s career cannot be understated: according to Claire Jones, who has written about the relationship between the two artists and Rodin’s career in the decorative arts, noted that “[By 1880], Rodin was already part of a broad network of academic sculptors, primarily instigated by his contact with Carrier-Belleuse [. . .].”[1] Carrier-Belleuse hired Rodin to assist him with work for the Hôtel de Païva, and he also hired him as part of the external staff at Sèvres. Through his contacts at Sèvres, Rodin met Edmond Turquet, who would later commission the Gates of Hell. Carrier-Belleuse also supported Rodin when he was accused of taking a cast from life in the process of making his sculpture Age of Bronze. So, rather than being an exhibition of Rodin’s work with a few Carrier-Belleuse pieces thrown in, this was a show that kept the focus on Carrier-Belleuse. The exhibition succeeded in displaying each of their works beautifully and without allowing Rodin to overtake the presentation.

No one has waited as long for this retrospective exhibition, which did not travel, to come to fruition than one of its curators, June Hargrove. Thirty-eight years ago, Hargrove wrote her dissertation on Carrier-Belleuse for the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University [one year later published as The Life and Works of Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse (New York: Garland, 1977)], clearly a labor of love, and she has continued to write about him and care about his art and legacy over these many years. Hargrove co-curated the exhibition discussed herein with Gilles Grandjean, the chief curator at Compiègne. Hargrove also wrote most of the accompanying catalogue, while Grandjean contributed thirty “notices,” or extended catalogue entries, on specific sculptures and decorative artworks exhibited in the presentation.

The exhibition began on the ground floor of the palace, just to the left of the grand staircase that led up to the main three rooms where the core of the presentation was held (fig. 2). The exhibition was entitled Carrier-Belleuse, Le maître de Rodin (Carrier-Belleuse, The Master of Rodin), and so Rodin’s thoughtful, patinated terra cotta bust of his mentor from 1882 (Cat. 124, Musée Rodin, Paris) opened the show on the ground floor. The bust displays Carrier-Belleuse’s age; his cheeks no longer have the plumpness that they had had in his youth, as seen in period photographs in the catalogue, and the ends of his mustache are trimmed short. Rodin, however, does imbue the face of his master with seriousness, intelligence, and gravitas. A bronze cast of this work was later placed on the older artist’s tomb, four years after its creation. Four other works, all created by Carrier-Belleuse, surrounded the introductory text and entrance to the exhibition: the Bacchante previously mentioned, which had spent more than one hundred years outside in the Tuileries (Cat. 17, 1863, marble, Musée d’Orsay, Paris); two large, extraordinary polychrome objets, Vase des Arts (Cat. 48, 1883, bronze “patiné,” Musée les Arts Décoratifs, Paris), made with the collaboration of Gustave-Joseph Chéret, and Vase des Élements (Cat. 103, 1878, bronze and hard-paste porcelain, Cité de la Céramique – Sèvres et Limoges), the latter created in the “pâte-sur-pâte” method, which creates a fine surface of transparent decorated layers; and finally Entre deux amours (Between Two Cupids, Cat. 19, 1867, marble, private collection, Paris), a delightful marble showing a cupid whispering into the ear of a young mother caressing a baby. The grouping of works was carefully selected to create a perfect plat de hors d’oeuvres to the exhibition. The visitor was immediately offered two examples of the artist’s Salon successes, two of his large-scale decorative works, and one portrait bust by Rodin, the latter establishing Carrier-Belleuse as the mentor of the leading sculptor at the end of the century.

Visitors ascended the grand staircase to the right and entered the exhibition proper on the second floor (fig. 3). A large reproduction of an illustration from Le Monde illustré showing artists converging in Carrier-Belleuse’s studio was displayed alongside the only painting in the show, a portrait of the artist from 1877 by Fernand Cormon (1845–1924). Again in both images the artist is shown as serious and thoughtful, and in the painting he is sporting the rosette of the Legion of Honor. The entire exhibition was accentuated by a dark purple color that was used on the bases, partitions, and wall texts. Once around the partition that held the painting, the visitor entered a grand space, bathed in natural light (fig. 4). The brilliant luminosity beautifully accentuated the works placed opposite the windows, but made the bronze works directly in front of the windows a little difficult to see (this may have not been much of a problem at different times of day).

To the right, a viewer could begin with a stunning group of portraits and an allegorical bust by the artist (fig. 5). Four terra cotta busts of female figures in the main, central space were particularly enticing: a posthumous portrait, possibly a model for a tomb sculpture, of the actress Aimée Desclée (Cat. 35, ca. 1874, Musée Carnavalet, Paris); a haughty bust, less decorative but full of expression, entitled Hortense Schneider (Cat. 34, ca. 1855, Musée National du Palais, Compiègne); a sweet-faced allegorical female figure, with a head heavy in grapes and vines, entitled Automne (Cat. 82, 1868, private collection, Paris); and an absolutely glorious bust entitled Buste de fantaisie, Marguerite Bellanger (Cat. 33, ca. 1866, Musée National du Palais, Compiègne), the face of which appears on the cover of the exhibition catalogue. The bust of Bellanger, who was a mistress of Napoleon III in the mid-1860s, is absolutely flawless in its execution (fig. 6); Carrier-Belleuse was known to finish his casts with his own flourishing hand. The loose, wispy curls of Bellanger’s hair are entangled with leaves, roses and rosehips, natural foliage that reappears below her neck. Her garment lightly covers her hair, cascades down over her shoulders, and concludes in a knot at her breast. The terra cotta garment is carefully and meticulously punched through to resemble the finest lace, complete with simulated embroidered details. Even the lips of the figure have tiny wrinkled lines to make them look perfectly real. The rich, creamy texture of terra cotta imbues so much warmth and life into sculpture. When one compares a cast sculpture, for example, Carrier-Belleuse’s Bust de femme avec des roses (Bust of a Woman with Roses, Cat. 42, 1858, iron, Musée de Picardie, Amiens) with any of his terra cotta busts, one easily sees how the details disappear, how the finesse fades, in the metal works. Maybe it is not fair to compare terra cotta with cast iron, the latter of which does not capture details very well and always appears particularly dull-looking in everyone’s sculpture. However, the superiority of the clay works over some of the metal sculptures is particularly evident in the art of Carrier-Belleuse, especially because he worked with such a fine touch in clay.

While Carrier-Belleuse seems to have had a special talent for sculpting gorgeous, impeccable female faces, his portraits of men are equally stunning. An example of this was found in a small but heroic bronze portrait, Napoleon III en Italie (Cat. 25, Napoleon III in Italy, 1867, Musée d’Archéologie Nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye), originally sculpted just after the Emperor’s victory at the Battle of Solferino in 1859. Another sculpture of the Emperor displayed here, composed as a marble herm (Cat. 23, 1864, Musée National du Palais, Compiègne) captures the ruler at possibly his finest hour—just before the crises in Mexico and conflicts with Prussia, and before his ill health and gallbladder stones debilitated him—and he seems to have the slightest hint of a smile beneath his finely trimmed mustache. And what a difference a decade makes: if one is familiar with Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s marble bust of the Emperor completed posthumously in 1873 [www.metmuseum.org], clearly Carrier-Belleuse captured the ruler at an equally melancholy but certainly better moment in his life and career. The spirited bust of Honoré Daumier by Carrier-Belleuse (Cat. 32, 1862, terra cotta, Musée et Domaine des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon) has rough tool marks in the clothing, but the face so truthfully captures his fellow artist that the sculpture seems to breathe.

The main, central space was a veritable feast of bronzes, terra cottas and patinated plaster sculptures, many of which were reduced versions of Carrier-Belleuse’s most successful Salon works (fig. 7). They included Ondine (Cat. 16, 1864, patinated terra cotta, private collection, Nashville), Diane victorieuse (Cat. 22, 1884, bronze, private collection, Nashville), and Angélique (Angelica, Cat. 18, 1866, terra cotta, private collection, Oise), which were exhibited near the center. Inspired by the poem The Frenzy of Orlando (1532) by the Renaissance poet Ludiovico Ariosto (1474–1533), Carrier-Belleuse’s Angelica is shown, as she usually appears in art, nude and bound to a rock, with waves of the ocean about to break over her tiny feet. The marble version of the sculpture, shown in the Salon of 1866 (but not present in the current exhibition), was widely discussed and appreciated, except by Auguste Clésinger, who compared the sculpture to Pierre Puget and Peter Paul Rubens (apparently an insult) (41). This criticism seems a bit unfair, especially since, when viewed with one’s head cocked so that the figure appears to lie on her side, Carrier-Belleuse’s sculpture clearly borrows the pose and lush decoration from Clésinger’s own Women Bitten by a Snake from 1847 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris). The most compelling of this group of small sculptures was La Messie (The Messiah, Cat. 21, after 1867, terra cotta, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Calais), a rare treatment of a religious subject by Carrier-Belleuse. The Virgin holds the Christ child above her head, with her arms fully outstretched; he in turn stretches out his tiny arms in a superb gesture that evokes both a blessing over the masses and a call for followers to join him. The original marble was shown to great acclaim in the Salon of 1867. He won a medal for the work in the Salon, and a gold medal at the Universal Exhibition of the same year. La Messie is today found at the Church of Saint Vincent-de-Paul in Paris, where it is placed in front of a gold mosaic niche that glorifies the figures and the sculpture.

The professional relationship between Carrier-Belleuse and Rodin was also treated in this main space. In the realm of nineteenth-century exhibition organizing, Rodin’s name has become like a spell: it is believed that when evoked in an exhibition title, his name bewitches the public, who then proceed, en masse, directly to the museum that holds the objects that bear his blessed name. Frankly, I found the title of this exhibition a bit irritating; the works of Carrier-Belleuse can certainly hold their own strength in an exhibition, and the idea to use Rodin’s name in the show’s title seemed to excrete directly from the marketing department. I am willing, however, to concede that the inclusion of Rodin’s works in the show were nevertheless applicable, because the two artists did work together, Rodin had no other teacher in his formative years, and the younger artist did assist Carrier-Belleuse with some architectural, decorative, and freestanding sculptures. While one does not need to be reminded of Rodin’s art to appreciate the work of Carrier-Belleuse, as this exhibition made clear, it was Rodin who needed Carrier-Belleuse’s support in his early years so as to get his career started. Yet a good number of the general art viewing public (that is, the art-loving non-specialists) may have in fact been attracted to the exhibition merely by Rodin’s name in the title. This sets up a difficult balancing act, but it was one that the curators played well. It was not a “bait-and-switch” exhibition either; if visitors were actually there only to see some works by Rodin, they would not have been disappointed, as the presentation included fifteen works by the artist, many of them from the early years of his career.

The evidence for Carrier-Belleuse’s influence over Rodin during his formative years became starkly evident in this section, especially when the works of both artists were viewed in proximity to each other. A marble bust by Rodin depicting the huntress Diane (Diana, Cat. 96, marble, Musée Rodin, Paris) bears the soft treatment of the tendrils of hair and the small facial features of many of Carrier-Belleuse’s busts of allegorical figures. A Bacchante by Rodin from around 1874 (Cat. 95, terra cotta, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) bears a distinct similarity with the aforementioned Automne by Carrier-Belleuse, though the younger artist lacked the lighter touch and the realistic, careful treatment of surfaces of the master. Some of Rodin’s own sculptures actually lost some of their luster when compared with Carrier-Belleuse’s pieces in this presentation. For example, Rodin’s Jeune femme au chapeau fleuri (Young Woman in a Floral Hat, Cat. 90, terra cotta, Musée Rodin, Paris), on its own a quite lovely bust (fig. 8), visibly lacks the delicacy of Carrier-Belleuse’s Jeune femme au chapeau à plumes (Young Woman in a Feathered Hat, Cat. 84, terra cotta, Private Collection, Frankfort), clearly seen when the two works are compared. Rodin’s sculpture of the young woman, with her heavy clumps of hair, bucked teeth and deeply gouged eyes, appears clumsy when judged against Carrier-Belleuse’s lush neo-Rococo bust of the woman in a feathered hat, with her soft curls, pouty, closed lips, and bouquet of flowers which seem to grow directly from the base of her sternum. Every frill, every detail of her dress, her jewelry, her feathers; all are treated with a careful hand, and one that knows how to work the clay to replicate texture of real objects. The hat worn by the Jeune femme au chapeau à plumes is modeled in such a way that the clay replicates the texture of felt. Luckily for Rodin and his enthusiasts, these two busts were exhibited in different rooms of the exhibition.

The question of authorship sometimes ensues when discussing some of Carrier-Belleuse’s decorative and architectural sculptures from the period when Rodin was working for him, and often one runs into a wall label in a museum, or sees a film, suggesting that Rodin was the definitive author of some sculptures signed by Carrier-Belleuse.[2] Rodin, however, should receive no more credit for “making” Carrier-Belleuse’s work than Camille Claudel receives for making Rodin’s work. Rodin was sometimes charged, as were many assistant modelers during the period, to transpose Carrier-Belleuse’s terra cottas into larger adaptations. An example of this situation of the studio is L’Innocence tourmentee par l’Amour (Innocence Tormented by Love, Cat. 76, 1871, terra cotta, Musée Rodin, Paris), a twenty-six inch high maquette for a larger version, modeled in part by Rodin, an example of which is found at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, but not shown in the Compiegne exhibition (www.cmoa.org). The catalogue discusses Rodin’s contributions to this work, and also notes that the two artists’ styles converge and then shift away from each other after the early 1870s, when “one finds little after from Rodin’s studio depicting groups composed of young women playing or being teased by children” [La convergence de style entre les deux artistes est évidente au tournant de 1870. On trouve peu après chez Rodin des groupes composés de jeunes femmes jouant ou taquinées par des enfants] (113). It is clear that once Rodin, as the saying goes, took off his master’s gloves and glasses, he produced his own unique and powerful work, sculptures that certainly modernized the medium of sculpture for at least the next three decades to follow. Yet, he owed much to his early relationship with Carrier-Belleuse.

The exhibition was not necessarily organized in a chronological fashion, which was on the whole refreshing. However, because of this, there was seemingly no logical way to view the exhibition. It was only later, after I had purchased the exhibition catalogue and read the catalogue numbers, that I realized I may have viewed the two side rooms in the “wrong” order. In my case, after looking at the entire central room, I went into a smaller room to the left of the main entrance, which was focused on “Le Beau dans l’Utile,” (roughly translated as “Beauty in the Useful”) and Carrier-Belleuse’s career at the national porcelain factory at Sèvres (fig. 9). Since Carrier-Belleuse did not become the director of Sèvres until 1876, it is possible that this room of the exhibition was to be viewed last. In any case, the “Beau dans l’Utile” room contained all manner of finery that would have been essential in the finest nineteenth-century homes, including clocks, candelabras, cassolettes, console tables, mirror frames, vases, and other such objets d’arts. An unusual but contemporary item, fueled by the European fashion for smoking Egyptian cigarettes after 1880, was exhibited here. Called a Service pour fumers (Smokers’ Service, Cat 118, 1883, hard-paste porcelain, Cité de la Céramique – Sèvres et Limoges, Sèvres), it is by far the most lovely and ornamental ashtray anyone has every seen. It had an area around the rim for placing fresh cigarettes, a flat area for stubbing them out, and three tiny vases (two held at an angle by scantily-dressed females) for placing the butts. An early sculpture of a Maltese dog (Musette, Cat. 41, 1855–68, hard-paste porcelain, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)[www.metmuseum.org], made in collaboration with Jean-Baptise Gille, would make Jeff Koons jealous. The highlight of this section of the exhibition was the sculpture installed in the center of the room, entitled La Charmeuse de serpent (The Snake Charmer, Cat. 50, 1878, bronze, gold, silver, and semi-precious stones, private collection, New York) (fig. 10). As with the Service pour fumers, La Charmeuse de serpent demonstrates evidence of Carrier-Belleuse’s treatment of Orientalist themes, albeit with less-overt eroticism. Commissioned for the vitrine of the jewelers Rouvenat and Lourdel at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, the female figure once held a cloisonné enameled snake in her right hand and a bird in her left, the latter bejeweled with “two thousand precious stones” (75). Even with the lost serpent and the replaced bird, the sculpture still sparkled in the exhibition under very well-placed lighting. The sculpture has something of the spirit and the decorative elements typical of the works of the Swiss sculptor James Praider (1790–1852), whose mixed-media sculptures Carrier-Belleuse would have certainly known. One of the main contributions that this retrospective made to art historical studies was to give equal importance to the artists’ decorative production and their academic sculpture. The lack of a specific direction for visitors to follow through the exhibition also seemed to equalize the works within the presentation.

The third room, at the far right of the entrance, was entitled “Creation and Diffusion” (fig. 11). It included at its center in the back, Carrier-Belleuse’s Léda de la cygne (Leda and the Swan, Cat. 73, ca. 1870, terra cotta, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). [www.metmuseum.org] The composition of Léda de la cygnet borrows from Michelangelo’s lost tempera painting of the same subject, known through copies. Michelangelo’s ghost reappears in the form of a historical bust (Michel-Ange, Cat. 81, ca. 1863, terra cotta, Musée National des Châteaux de Malmaison et Bois-Préau, Rueil-Malmaison), wonderfully arranged with a lively face, parted lips, wind-swept beard and tuft of hair, and, of course, his famous broken nose. A reduced version of this bust, borrowed from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Cat. 79, before 1883, silvered bronze), illustrated the point about how Carrier-Belleuse’s art was “created and disffused,” but once again the metal casts pale against the clay works [www.metmuseum.org]. The terra cotta bust of Michelangelo was nicely placed opposite the historical bust of the English poet John Milton (Milton, Cat. 80, ca. 1863, terra cotta, Musée National des Châteaux de Malmaison et Bois-Préau, Rueil-Malmaison), whose softly closed eyes give him the appearance of someone, deep in thought, or sleep, or death. Carrier-Belleuse’s historical portraits have as much liveliness as those busts that he modeled from living persons.

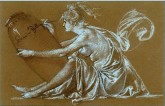

In addition to some more loosely handled terra cottas and plasters in a case (including a study for the torchères for the Opera Garnier) and stereoviews of Carrier-Belleuse’s sculptures as shown in 1867, also presented in this room were numerous drawings in various media such as ink and chalk. The white chalk drawings on brown paper were particularly impressive, for example Femme assise tenant une amphore (Seated Woman Holding an Amphora, Cat. 54, ca. 1860, chalk on brown prepared paper, Musée Bouilhet-Christofle). The lightness and attention to line is as evident in Carrier-Belleuse’s drawings as in his terra cotta works, as seen in this amusing drawing where the woman signs the artist’s name to the amphora (fig. 12). Drawing remained important to Carrier-Belleuse’s creative process, and clearly he was a master in this medium as well as in sculpture (88).

It is only in very recent times that the sculptors of the mid-nineteenth century are being given the serious attention they deserve. The year 2014 saw exhibitions focused on such contemporaries of Carrier-Belleuse as Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux and the female sculptor Marcello (Adèle d’Affry); all three of them were at the height of their careers at 1870.[3] They were the sculptors of the generation before Rodin, and they worked tirelessly to position sculpture as a modern art form that, whether considered fine or decorative, should be found in people’s homes, on the streets, in the parks, in cemeteries, and in other public arenas. The art of Carrier-Belleuse also defines a moment in art history where fine and decorative sculpture seemed to briefly and successfully merge. Art historians have kept our sculptors and our decorative artists in different academic corners, but this exhibition showed contemporary viewers that the relationship between sculpture and decorative arts was not always so clearly defined, and often in the period the connection between the two was far more fluid. Carrier-Belleuse treated all of his works, whether they were drawings, sculptures or decorative objects, with the same high level of excellence. He died young, by our standards, at the age of sixty-three. Yet, through this well constructed exhibition, he has finally had his retrospective, 127 years after his death. It and its accompanying catalogue will certainly inspire renewed interest in the decorative arts in France, and in this well-deserving sculptor.

Caterina Y. Pierre, PhD

City University of New York at Kingsborough

caterinapierre[at]yahoo.com

caterina.pierre[at]kbcc.cuny.edu

Related Links:

RMN Press Release:

http://www.grandpalais.fr/fr/evenement/albert-carrier-belleuse

University of Maryland Press Release:

http://arthistory.umd.edu/professor-hargrove-curates-ground-breaking-exhibition-albert-carrier-belleuse

Artactu.com Press Release

http://www.artactu.com/exposition-carrier-belleuse.-le-maitre-de-rodin-article003644.html

Review, La Tribune de l’Art

http://www.latribunedelart.com/carrier-belleuse-le-maitre-de-rodin-5189

Review, Culture Box, France TV Info:

http://culturebox.francetvinfo.fr/expositions/sculpture/hommage-a-carrier-belleuse-le-maitre-de-rodin-au-palais-imperial-de-compiegne-161475

Review, Le Parisien

http://www.leparisien.fr/espace-premium/oise-60/premiere-retrospective-en-france-du-maitre-de-rodin-carrier-belleuse-22-05-2014-3860289.php

I wish to express my thanks to Florence Le-Moing and Anais Tridon of the Réunion des Musées Nationaux – Grand Palais for their assistance and for providing the images for this review.

[1] Claire Jones, Sculptors and Design Reform in France, 1848 to 1895: Sculpture and the Decorative Arts (Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate, 2014), 112.

[2] The film I am thinking of here is the documentary Rodin, the Gates of Hell, produced by Gerald and Iris Cantor and David Saxon (West Long Branch, NJ: Kultur, 1981), DVD.

[3] The two exhibitions I mention here were New York and Paris, 2014, The Passions of Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (Metropolitan Museum of Art and Musée d’Orsay) and Fribourg, 2014, Marcello (Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Fribourg).