The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Pigs abounded on French postcards in the medium’s golden age, ca. 1900–1914. Pig postcards are a remarkably lively, compelling, but largely forgotten feature of the Belle Époque’s richly varied, rapidly evolving visual culture. These cards offer up for study a fortuitous and suggestive conjunction: the commonest of farm animals with a long history as an indispensable food source, represented massively on a new medium that became ubiquitous and influential, precisely at a time when the pig’s role in French culture and agriculture was starting to shift significantly. Scrutinizing pig postcards can thus reveal a good deal not only about the surprising scope and impact of visual media during this period, but also about changes in pork production that were characteristic not only of the French but also of the broader Western food system’s incipient modernization.

A traditional symbol of plenty, the pig was a staple of the Gallic diet and an integral part of festive occasions, closely linked to the peasant calendar’s cycles of fat and lean, and to seasonal slaughter and consumption. Many Belle Époque pig postcards depict this traditional world of small-scale farming, local marketplaces, and time-worn ways of preserving, preparing, and serving food. Many others probe what Alberto Capatti calls our “alimentary modernity,”[1] as they portray pigs sucked into sausage-making machines, sliced in half by train wheels, driving automobiles, piloting airplanes, or surrounded by abundant ice and snow—figuring, however fancifully, emergent methods for processing, transporting, and conserving meat. Considered as a whole, the corpus of pig postcards registers an ongoing shift from the ritualized sacrifice of individual pigs to large-scale, rationalized slaughter, and more broadly from artisanal and local to industrial and remote food production. These changes, happening across the developed world at the time, were experienced in France with a particular imaginative intensity, as the inventiveness, abundance, variety, and historical double vision of such cards suggests. Looking both backward and forward, these images exhibit a striking mix of nostalgia, regret, anxiety, and enthusiasm, overemphasizing at once the persistence of vanishing customs and the impact of radical transformations that were beginning to take hold.

In recent years, increased scholarly and curatorial attention is paid to old postcards, giving rise to a new field that could be called “postcard studies.”[2] These developments have been prompted by the flourishing study of popular visual culture in general, by the sharing of major postcard collections with museums and libraries,[3] and by the rise of online auction sites that have made these specific artifacts more readily available to researchers than ever before. As several recent books and an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston demonstrate, the illustrated postcard was in its heyday a vibrant, versatile medium.[4] Postcard studies have shown that, while individuals occasionally created and mailed postcard-like documents before, the first ever postcards issued by an official, governmental entity circulated in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1869, with new postal legislation allowing for quick, easy, inexpensive sending.[5] The medium caught on quickly, as it offered a revolutionary new means for transmitting messages rapidly and inexpensively to places near and far, and a vogue for postcards soon spread around the world.[6] At first, postcards bore no images, then small illustrations were added. By the turn of the century, the space devoted to the image had expanded to fill one side.[7] Across the globe in the years between 1900 and World War I, the height of postcard mania, billions of illustrated cards were produced, sold, sent, and collected.[8] Combining images with various sorts of text (captions, inscriptions, postmarks, addresses), these richly-layered visual-verbal documents engaged in a range of revealing ways with contemporaneous issues and developments. And they reward our careful attention. As Benjamin Weiss insists in the exhibition catalog for The Postcard Age: “Postcards survive in uncountable numbers. Perhaps because of that, they tempt us to look quickly. But if you slow down and look at them one by one, they provide unusually vivid access to the past.”[9] Or, as Leonard A. Lauder asserts in the preface to the same catalog, “postcards open countless windows onto a broader collective past.”[10] I would add to this that postcards also look forward in time, by confronting the novelties of their day and, in the process, anticipating the future.

A number of studies have considered Belle Époque postcards’ relationship to such developments as the rise of tourism and colonialism, the emergence of international celebrity culture, and the impact of new technologies like the automobile or airplane, or even of old technologies like dams or bridges that were revolutionized by new materials and construction techniques.[11] To date, however, no one has focused on postcards in relation to the profound shifts in food production that were underway at the time, and Belle Époque pig postcards are of particular interest in this respect. By examining and interpreting them we delve into the imaginaire of a nation caught between traditional foodways and modern food production, and between a predominantly rural past and an increasingly urban, industrialized future. Such oppositions are significant historically, and still relevant to debates today that pit dreams of returning to traditional (“artisanal,” “local,” “organic,” “seasonal”) food production against the realities of a now solidly-entrenched industrial food system. This is, moreover, an area of inquiry at the crossroads of three burgeoning fields—visual culture, food studies, and animal studies—whose intersections have attracted recent scholarly interest, and hold promise for further investigation.[12]

Pigs and Postcards

Next to cats and dogs, pigs were the animal featured most frequently on Belle Époque postcards, and the output of pig postcards was as varied as it was substantial. Using online auction sites to sift through thousands of these artifacts, I have put together a representative corpus of over one hundred individual cards, virtually all dating from 1900 to 1914, with a few published during the Great War or immediately after, but continuing in the same vein as before. They represent their subjects across an extraordinary range of styles and registers, and do so through caricature, realistic illustration, photography, or combinations thereof.

In my discussion of these cards, I also include some relevant chromos, chromolithographic trade cards. Used for advertising instead of correspondence, these were similar to postcards in their format, themes, broad dissemination, and interest to collectors.[13] Trade cards were in fact the “direct commercial ancestor” of the illustrated postcard, as Benjamin Weiss explains:

Businesses issued these colorful lithographed cards to tempt customers and collectors alike, sometimes selling them but more often just giving them away. In the 1870s and 1880s, people collected trade cards with an ardor similar to that which they brought later to postcards.[14]

Though postcards surpassed their predecessors in popularity from the turn of the century on, trade cards continued to be produced during the Belle Époque. It is harder to date trade cards with certainty, since they lack postcards’ date notations, postmarks, and historical formatting changes (e.g., undivided vs. divided backs). However, the ones discussed here are all roughly contemporaneous with the postcards that make up the bulk of our corpus.

In his 1891 tale “The Little Pigs,” humorist Alphonse Allais imagined the residents of a town—with the appropriately charcuterie-inflected name Andouilly—afflicted by a mania for making innumerable little pig effigies from soft pieces of bread.[15] Within a decade, the mass-produced, illustrated postcard would offer the French another inexpensive medium for depicting pigs obsessively.[16] Pig postcards captivated the French imagination during the Belle Époque, as evidenced by their abundance, and by their frequent use of mises en abyme, focusing not just on the pigs they represent, but also on the process of representing them. Some (fig. 1) give formulas for how to draw cartoon pigs, treating the animal as a common, necessary part of the period’s visual culture. One postcard (fig. 2) conveys pigs’ place in artistic representation through a painter’s palette, blank except for three circular frames containing pigs’ heads rather than pigments, with three brushes alongside dipped respectively in blue, yellow, and red—as if these paints had come from the hog vignettes. Pigs are a fundamental visual element, this suggests, tantamount to primary colors. Other cards highlight artists portraying pigs. In one trade card captioned ARTISTIC INSPIRATION (fig. 3), a painter in front of his easel inside a barn looks at the porcine young woman before him, and the graceful, almost equine pig behind her, for inspiration. Elsewhere (fig. 4) an artist paints a pig in a farmyard setting, as a peasant nearby exclaims, “Ah! What a filthy profession.” Ironically, the old man with his mud-encrusted clogs, who deals with pigs daily, dismisses painting as “filthy” work. And another trade card entitled The Painter in the Village (fig. 5) also juxtaposes an urban, bohemian painter with quaint locals who watch him as he sits on an improvised scaffolding of two barrels and a plank, painting a pig on the outside wall of the village charcuterie.

In his incisive 1974 essay, “The Postcard Vision,” artist and avid postcard collector Tom Phillips speculates about the potential “importance of the postcard as a source document for the social historian and anthropologist.”[17] Belying its apparent simplicity, he suggests, the postcard relates in complex, surprising, and profound ways to the everyday, present reality it seems to reflect. “Life aspires to the condition of the postcard,” Phillips asserts, “more than the postcard aspires to the imitation of life.”[18] Along similar lines, he claims, “The postcard creates the future of the site shown in it.”[19] Seen this way, the postcard is close to what commentators like Jean Baudrillard or Umberto Eco have characterized as the simulacrum, as not a copy of the real, but as somehow truer, and more captivating than reality itself. The postcard may thus be seen as a form of hyperreality, a sort of parallel universe or, as Phillips suggests, “the postcard is its own world (as if it described a distant but related planet).” This is a wondrous realm where miracles are “commonplace,” as if in a dream; indeed he maintains that “The postcard is to the world as the dream is to the individual.”[20] Collectively, cards convey what Phillips calls “the postcard vision,” rich in creative, imaginative possibilities that extend far beyond specific postcards’ ostensible literal meaning or documentary value.

Accordingly, while no single Belle Époque pig postcard tells all, together they paint a fascinating, nuanced picture of a world in transformation, but still rooted in a past in which pigs played a key role in the diet as in daily life. The cards get at all this in many suggestive ways, probing the sometimes unsettling, even uncanny closeness (both in resemblance and proximity) between pigs and humans; the long-standing conjunctions of terroir and tradition that persisted; and the sacrificial rituals that endured, yet were on the brink of yielding to a new regime of industrialized slaughter, as pigs themselves, like methods of pork production, seemed to be running headlong into modernity.

Pigs and People

“As for me who’s only good for eating, my death is assured,” cries the pig in La Fontaine’s fable Le Cochon, la Chèvre et le Mouton, comparing his plight to that of his fellow creatures, the goat and the sheep, as they’re hauled to market.[21] Unlike other farm animals that were also useful when alive (cattle pulled plows and, like sheep and goats, they supplied milk; sheep provided wool as well and hens laid eggs) pigs were raised for what they yielded when dead—meat and especially fat (the all-important lard in the “larder”), but also bristles, skin, or bladder. Cheap to raise, fast to grow, wondrously prolific, and incomparably bounteous—every part gets consumed, from snout to tail[22]—the pig is arguably the most useful of farm animals, but that utility can only be realized with the pig’s demise. For as long as humans have kept them, this state of affairs has conditioned our relationship to pigs, focusing attention on the necessary outcome: our killing them. In recent times, however, the nature of this inevitable ending has changed profoundly, and the Belle Époque in particular was a pivotal period of transition from traditional sacrifice to modern, industrial slaughter.

From ancient Gaul through the Middle Ages, pigs were fattened in forests, where they reproduced regularly with wild boar, keeping their genetic stock wilder; indeed, images from this period display the “extreme rusticity” of pigs hairier, darker, longer-legged, and fiercer-looking than their modern counterparts.[23] The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw new demands for wood, however, particularly for shipbuilding, and the resulting deforestation led to reduced pork production and consumption. By the eighteenth century, there were four times fewer pigs relative to the human population than in the thirteenth century.[24] With supply diminished, and the gabelle or salt tax raising the cost of the salt needed for preserving meat, prices rose. The wealthy could still afford—but largely spurned—pork, turning instead to veal, now considered more refined.[25] Meanwhile common folk had trouble affording pork products for traditional dishes from cassoulet to crépinettes, pois au lard to potée auvergnate.

Yet forces underway would reverse these trends. Starting in the mid-eighteenth century, potatoes were introduced in certain regions, providing cheap, plentiful nourishment for pigs. Over the following one hundred years they would reach the entire country, making it possible again for farmers across France, no matter how modest their means, to keep a pig or two. And the revocation of the gabelle under the Revolution (even if other, less despised salt taxes would persist until 1946), lowered the cost of preserving the flesh.[26] By the middle of the nineteenth century, the author of an agronomic handbook on raising swine could declare confidently that “The pig is an animal of prime importance in a farm,” found everywhere, even in poor households lacking any other kind of livestock. Pigs alone thrive “in all regions” and constitute “the most tangible form of wealth in many places . . . the sole resource of many settlers and unfortunate proletarians.”[27] Or as Michel Pastoureau remarks, “Once again the pig came to represent for the European peasant a kind of safety net, just as it already was in the Middle Ages.”[28] And this cottage pork production renewal offers an alimentary counterpart of the flourishing medievalism in nineteenth-century French arts and letters: a seemingly simple, joyous return to the Middle Ages’ neglected if not entirely forgotten bounty. Indeed porcophilia and nineteenth-century medievalism intertwine tellingly in a text like Maguenousse’s Histoire de Boulot: Impressions d’un cochon du Moyen Âge, illustrated by Robert Tinant, the tale of a runaway pig caught, killed, and appreciated more dead than alive: “He is more appreciated as sausage meat than he ever was in flesh and bone.”[29] Such self-conscious medievalism indulges in much the same archaic fantasy that we find at work in many Belle Époque pig postcards.

But simultaneously with this apparent return to the Middle Ages, changes were underway that would modernize and eventually completely industrialize pork production. Attempts to improve porcine races for human use began in England around 1740, leading to larger, stockier pigs that yielded more meat and lard. Things evolved slower in more deeply, extensively rural France, but the English trends were popularized through agronomic publications and competition for prize animals in the increasingly popular and influential comices agricoles, or agricultural fairs.[30] By the 1860s the new breeds had been introduced throughout France and were progressively replacing older, less profitable varieties.[31]

In addition to selective breeding, the standardization and commercialization of feed (which included growing amounts of agricultural and later industrial by-products), as well as the increasing confinement of pigs in specially designed structures, made production more efficient. Over time refrigeration, modern transportation, and the development of large modern slaughterhouses would further streamline and thus boost production. Still, through the mid-twentieth century, across rural France, individual pigs continued to be raised and slaughtered as they had been for centuries, with the time-honored ritual of the tue-cochon, literally the “pig-kill,” carried out at the farm, among family, friends, and neighbors, who gathered for the sacrifice, butchering and preparation of the meat, and ensuing festivities. But such holdouts in the face of inevitable modernization were effectively ended in 1971 by an executive order that required pigs be killed in a slaughterhouse, with only tightly-regulated exceptions for animals consumed exclusively by the family.[32] The long reign of homemade boudins drew to a close, ushering in the age of cellophane-wrapped, supermarket pork chops.

Forces already in motion during the Belle Époque—urbanization, the accompanying rural exodus, new technologies of all sorts—would in the long run industrialize food production massively, estranging the French from tradition, terroir, and the natural realm in general, alienating French consumers from how their food is made, and particularly from how living things become dinner. While profound, these transformations were gradual, or at least progressive, with rapid advances in food production accompanied by surprising holdovers. In this respect as in so many others, the Belle Époque stood at the crossroads of opposing historical tendencies. In contrast to so much modernization of the food industry at the time, the nineteenth-century revival of widespread medieval-style, small-scale, artisanal pork production continued—realizing the ideal not of Henri IV’s “chicken in every pot,” but rather of a pig on every farm, supplying traditional pork products to enjoy throughout the year.

In a general way, modernizing trends renegotiated connections between humans and animals. For example, dogs had long been used as beasts of burden, to haul carts with human passengers or cargo, especially in coal mines and on rural mail routes: man’s best friend condemned to hard labor. But in France, the latter part of the nineteenth century saw new regulations banning such use of dogs, alongside a telltale flurry of postcards evoking these vanishing practices.[33] The French were investing ever more heavily in their affective links with animals deemed pets—the novel pet cemetery in Asnières opened in1899, for example.[34] So for the most part, the period witnessed an ever-sharper divide, within human-animal relationships, between domesticity and utility. Cats and dogs fell on the side of domesticity; cattle or sheep, increasingly subjected to large-scale industrial production, on the side of utility. Pigs however, in a historical anomaly and a kind of animal exceptionalism, increasingly exemplified both domesticity and utility.

Over time, and especially across the nineteenth century, pigs and their circumstances had changed. Bred for greater domesticity, and fattened on the farm rather than in the woods, these more docile, more dependent creatures lived in closer quarters with humans, almost as members of the household. This fostered in the French the sense of a more intimate connection with pigs, a cozy vision of communality as well as of ostensible continuity with ancestral closeness to the land, and to the good things raised there.

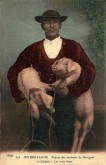

On a number of Belle Époque postcards, individual peasants or whole families pose proudly with their pigs, in images that bespeak both physical and sentimental closeness. On some, captions make this more explicit, as peasant women declare that they prefer piglets to their men, or beg spouses to grant their favorite little hogs clemency—notably in a series of cards produced by St. Brieuc-based Breton regionalist and postcard publisher Émile Hamonic, illustrating the song “The Little Piglet” by his friend the Breton author, composer, and singer Théodore Botrel (fig. 6). But might the husbands share such affection for their swine? One card (fig. 7), in which a Breton peasant man in traditional garb poses for the camera holding a little pig under each arm, is titled IN BRITTANY Peasant from the Huelgoat and Carhaix area—the three Friends. On the surface, this could appear a straightforward paean to pig-human companionship—set, appropriately it seems, in a remote, inland part of the Finistère that remains a pork-producing area today. Upon closer examination, however, the card proves ambivalent in important ways. Unlike postcards of peasant women with their beloved pigs, tenderness is conspicuously lacking here. The man has a determined look in his eyes as he gazes straight ahead, not downward at his would-be “friends,” held unceremoniously, almost roughly, as they dangle, perhaps resisting his grasp. Indeed the pigs would have good reason to squirm, since they’re attached to ropes, which is typically how they would be led to market, to be sold either for immediate consumption, or more likely for fattening and eventual harvesting. However the women folk might feel about them, for the serious fellow here these pigs seem less objects of affection than commodities, less a sentimental entanglement than business as usual.

But is that the whole story? Not really, for scrutinizing the circumstances of the card’s production complicates matters further. While there were a number of leading postcard publishers based in Brittany at the time, like Nozais and Artaud in Nantes,[35] this card was produced by a major Parisian firm, E. Le Deley. Though it is not possible to know for sure how this provenance affects the card’s perspective, one could certainly exclude the local pride that might accompany a card produced in St. Brieuc, Nantes, or Quimper, and suppose instead the condescending eye of the capital lumping together the “three Friends,” a phrase suggesting not just camaraderie but equivalency between peasant and pigs, seen as similarly subhuman. At the same time, the man’s costume seems too clean and perfect for a real, working, pig-handling peasant, particularly in our hand-colored version, with his shirt a bright white, and his jacket a rich, velvety maroon, punctuated by shiny, brass buttons, all of which stands out too crisply against a telltale studio backdrop. Posed and contrived, this is no authentic scene, but rather an attempt to evoke one, crafted in a studio perhaps not in Brittany but in Paris, far from any local hog raising, and featuring a “farmer” who might well be a professional model.[36] The inauthenticity is telling for, despite whatever ironic distance the caption implies, this card betrays a nostalgic desire to linger upon a kind of primal scene of the peasant and his pigs, a vision of their closeness to each other and to the land. It is a prototype for the urban fantasy of terroir that has become such a standby in advertising modern, industrially produced food products, awash in verdant fields, happy family farms, and imaginary places names like “Nature Valley” or “Hidden Valley,” the ersatz appellations d’origine for brands of processed granola bars and salad dressing.

At times in this corpus, humans’ connections to pigs seem too close even for comfort. In one emblematic card (fig. 8), set in a vague, undefined farmyard setting, a pig pokes its long tongue into a peasant woman’s nether region as she crouches to relieve herself—an intimate scene of interspecial cunnilingus, coprophagia, urophagia, or some combination of these. The title, adopting the opportunistic pig’s perspective, reads, Ah! Maman. Profitons-en pendant que c’est chaud (“Ah! Momma. Let’s get it while it’s hot”). Telling correspondences underline the link between human and swine: the pink flesh of the woman’s rump matches the pig’s adjacent snout, while the bright red of its tongue echoes her flushed cheeks and bonnet. The startled look on the woman’s face also mirrors our astonishment, as viewers, over this unsettling spectacle. And the card’s depiction of the space is as disorienting as whatever is transpiring there. A clumsy, curious partition runs between the characters; however the perspective is all off, and it’s unclear how the structure is standing, what’s supporting it, or why, instead of ending cleanly along its upper edge, it appears to fade into thin air. This is a badly drawn but revealing illustration. Its ineptness points to an underlying malaise over changes underway at the time that were transforming venerable patterns of interrelation and interdependency with animals, so closely bound up with how food was cultivated, prepared, and consumed. The woman, her stereotypical rustic clogs perhaps a deliberately archaic touch, also wears a sort of sloppy Phrygian cap, with her blue skirt, white blouse, and red headgear emulating the French flag, casting her as a kind of peasant Marianne, a French Everywoman. Meanwhile, within a farmyard context in which the pig is presumably being raised for harvesting, its outrageous incursion into the woman’s private parts and functions satirizes an idealized eternal chumminess with swine that, like the tradition of peasants forever shod in clogs, was already on the wane. At the same time, the seemingly substantial yet visually unconvincing and practically ineffectual boundary figures a still largely hypothetical divide between humans and pigs that would materialize and solidify over the decades ahead, as the French became more and more cut off from the animals that supplied their food—including, eventually, pigs.

Instead of hypothetical separation, numerous other cards take an equally fanciful but opposite tack, conjuring up scenes of hypothetical closeness. Unlike more plausible images of pigs with peasants, these cards take swine from the farm into the drawing room, as elegant women or couples care for and play with little porkers. In one good-luck card that features four-leaf clover motifs and circulated in the Côte-d’Or in 1908 (fig. 9), a stylishly-dressed lady bottle-feeds a piglet cradled in her arm, while the rest of the litter surrounds her, jumping up eagerly toward the multiple flounces of her dress, like pig siblings vying for their mother’s abundant teats. In another (fig. 10), a fashionable couple dressed for a night on the town plays with a litter of piglets perched upon a lovely art nouveau side table.[37] Such incongruous mixing of high society with lowly farm animals suggests a nostalgie de la boue reminiscent of Marie-Antoinette’s frolicking with perfumed cows in her Hameau at Versailles. However, there does not seem to be any evidence that such encounters actually took place in Belle Époque France. Still, these fantasy scenes of pigs as genteel playthings point to pervasive notions about pigs’ newfound domesticity, and to a lingering desire to retain a personal connection to the land, however implausible that might be.

While vegetarianism was gaining some ground in France at the time, out of both ethical and health concerns,[38] most of the French continued to eat meat, so no matter how sanitized a view of human-pig relations got served up on such cards, people could not overlook the traditional role for pigs, condemned to death to provide people food. On one card sent from Lyon to London in 1901, for example, the image and inscription are revealingly at odds (fig. 11). A young woman in an elegant silk dress and long white gloves cuddles with a bonneted pig on her lap. Below the pair the polite façade seems to continue, with cordial greetings from “Henriette.” But then the postscript, “I should inform you that a sausage is on its way,” conveys a different, far more realistic view of a little pig’s destiny—as pork, not as pet. On this card, and more broadly across the whole corpus of Belle Époque pig postcards, seemingly contradictory visions coexist: the pig as delightful companion, and four-legged larder.

Many cards depict pigs as humans, whether in human dress (from tutu to top hat, depending upon the context), or doing human things (ice skating, reading, riding bikes or cars, smoking pipes, sharing a four-poster bed, etc.), or both. Others, however, construe the identification conversely, casting humans as pigs by implication. This may involve women in more or less flattering contexts, like the attractive young woman mentioned above, playing a loving mama pig nourishing her offspring; or the stouter lass posing in the barnyard scene entitled ARTISTIC INSPIRATION (fig. 3). More commonly, cards address a male recipient as “vieux cochon” or “sale cochon,” “old” or “dirty” pig, with the accompanying image illustrating the identification. One particularly suggestive example (fig. 12) that circulated in Auvergne in 1907—entitled NATURAL HISTORY, just like the naturalist Buffon’s magnum opus—showcases a creature with a pig’s body and man’s head, surmounted by the humorous couplet, “Here, from all of Buffon’s animals, is the one who resembles you the most, you DIRTY PIG!”[39]

Pigs, in Michel Pastoureau’s apt formulation, are humankind’s “ill-loved cousin,”[40] close to us in so many ways: biologically, anatomically, culturally, gastronomically, temperamentally, sexually, and even intellectually. Indeed pigs’ keen intelligence, housed in a vessel so oft considered ignoble, both fascinates and unsettles. Reaching back in time and across cultures, further contradictions abound in our age-old love-hate relationship with pigs: even before their increasingly intense domestication during the nineteenth century, pigs could be seen as at once tender companions and a thrifty, dependable, cherished food source. The incredibly polyvalent pig has been regarded as the most valuable and vilest of animals, the object of lavish, blanket praise for its delicious, snout to tail utility, and of endless scorn and suspicion for its supposed moral shortcomings. Across the centuries, representations have ranged wildly from praise to blame, depicting pigs as the best and worst of creatures, their embodiment of all virtues and vices underscoring their real and perceived proximity to humans.[41] In France during the Belle Époque, when a mix of historical forces was at once bringing pigs closer and distancing them from people, postcards puzzled with new intensity over pigs and pork identified not just with humans in general, but with the French in particular.

Pigs into Frenchmen[42]

Across the territory that has become modern France, traditional pork production occupied a key place within a whole complex of time-honored means for supplying food, like local raising, slaughtering, processing, and consumption of livestock, in a tightly-knit web of community, custom, and belief. The broad lines of these practices long remained constant. Whether in Brittany, Alsace, Auvergne, or Languedoc, people followed much the same calendar for raising and harvesting their pigs. They used blood collected from the sacrifice to make boudins, consuming some of the meat fresh while preserving the rest through salting and smoking, rendering the all-important lard, and so forth, utilizing the whole hog for culinary and so many other practical purposes, from medicine to art, with bristles used for paintbrushes or bladders for storing paint. In France, and more broadly throughout Europe, these common threads formed what Pastoureau calls “a true pig civilization.”[43]

There were, however, innumerable local variations in husbandry techniques, recipes, terminology, and folklore. Accordingly, pig postcards offer a cornucopia of terroir and tradition, getting at the cultural and culinary specificity of distinct, diverse French regions. Pigs figure in endless scenes of farm, village, and town life, as cards highlight localities or regions and their different pig-related customs, including hog races in village festivals, truffle hunting in the Périgord, and local dishes like Andouillettes de Troyes (chitterling sausage from Troyes) or Pieds de cochon de Ste. Ménéhould (pigs’ trotters from Ste Ménéhould). There are market scenes galore, and in some (fig. 13) the parties to a transaction haggle in patois, adding local, linguistic color, and generally a bit of folksy humor as well (“You want more money for your pig because you gave it special food? Did you also teach it to read and write?”). On the same cards, general titles like À la Foire or Au Village (“At the Fair” or “In the Village”) are inevitably in French, with dialect or patois thus subsumed under the national language, and by extension the region subordinated to the nation.

So much a part of the traditional French cultural and gastronomic landscape, pigs also permeated the physical landscape, as evidenced by abundant pig-related place names across France.[44] And postcards feature pigs discerned in rock formations, like the results of a collective Rorschach test for a population with pigs on its mind (fig. 14).[45] Similarly, one noteworthy card made in Lyon and promoting this city known for its pig-based charcuterie, is circumscribed by the silhouette of a pig, which frames a collage of color postcard views representing the town’s principal monuments (fig. 15). The outline of this large, colorful pig stands out against a muted, repeating pattern of much smaller, shadowy pig silhouettes that, according to the card’s visual logic, represents other French localities, like towns on the map marked with pig icons rather than dots. By extension, by projecting the background pattern beyond the frame—as partial silhouettes along the edges invite us to do—this composition envisions the entire country in the image of its innumerable pigs, and the juxtaposition between a Lyon postmark and a République Française stamp echoes this dialogue between regional parts and the national whole. In contrast to a by-then established tradition of French gastronomic maps,[46] which highlight different characteristic food products for each region (mustard for Meaux, ham for Bayonne, champagne for Reims, etc.) the map of France implied by the Lyon card would instead locate pigs everywhere. Whatever else might differentiate French regions, culturally and gastronomically, they share this common connection to swine. Many other postcards associate not just pigs but also specific pork specialties with local monuments. Pigs and particularly the dishes they yield could be understood as monuments, as lieux de mémoire or realms of memory, indeed as part of what has come to be seen today as the “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity,” a cultural heritage comparable to tangible artifacts like paintings, statues, or buildings.[47] To wit, on a card entitled SOUVENIR OF Ste MÉNÉHOULD that celebrates the town’s renowned pieds de cochon (fig. 16), a little chef riding a hefty hog hoists a large platter with a giant pig’s trotter surmounting a pile of postcards that cascade out into the rest of the composition, displaying all of the town’s main historic sites. The pied de cochon, seeming most monumental of all here, looms atop and dwarfs the cards of the town’s main tourist attractions. Backward-looking in its honoring of local historical, architectural, and especially culinary traditions, the card is also resolutely forward-looking in its use of stylish art nouveau lettering and its good-natured homage to the contemporary postcard craze.[48] While a fat sow may not be the swiftest way of getting around, postcards set in motion and dispersed in every direction offer a speedy alternative, a model of rapid circulation that was indeed taking France and much of the rest of the world by storm at the time.

Another, similar, Ste Ménéhould card pushes further still in these directions (fig. 17). The text, vaunting pigs’ trotters as a local specialty, is nearly the same as that of the SOUVENIR OF Ste MÉNÉHOULD card and uses a similar art nouveau typeface. Here the oversized pied de cochon is suspended, gondola-like, from a looming dirigible, whose shape is formed largely by a postcard collage of local views, like a giant, airborne postcard display. Indeed the composition offers a mise en abyme of postcard production, distribution, and circulation. As the dirigible flies by, it frames a perfect postcard view of the distinctive Hôtel de Ville, or town hall, flanked by matching rows of trees—a transparently contrived scene that places a cut-out photographic image of the town hall within a hand-drawn landscape. The well-ordered rows of cards on the dirigible emulate their presentation in racks at newsstands or train stations. And where the first Ste Ménéhould postcard just sets cards in motion and infers their broader circulation, this one provides an exciting new mode of transportation to whisk them far away. It suggests much about what aviation would bring in the years ahead, from aerial postcard photography, to airmail, to air transport of foodstuffs, at a time when developments like these were either not yet common, or had not yet evolved, but when their effects and impact could already be imagined. In a larger sense, both Ste Ménéhould cards get at the conjunction of new and improved transportation and media technologies that were leading toward ever-greater dissemination of images, messages, passengers, and goods, bringing people to France’s diverse regions, and the products of those regions to the people. Cards like these prefigured the vogue for regional cuisine after World War I, as figures like Curnonsky and Marcel Rouff, with their 24-volume La France Gastronomique,[49] would seek to recuperate regional specialties as part of a coherent, or at least comprehensive national cuisine. But more generally, postcards that recorded, promoted, and celebrated what diverse locales had to offer—from products of the terroir to noteworthy buildings—were part of a broader evolution that was forging regional differences into a synthetic vision of the French nation.

This nascent national vision was accompanied by a new understanding, an awareness of French geography, a veritable “discovery of France.”[50] One notable feature of this was a new fascination with the land-sea dichotomy—a central structuring element within French geography and gastronomy. And in various telling ways pig postcards get at conjunctions of land and sea. For example, a card in a series of Breton views foregrounds pigs grazing dockside at the Port of Légué in St. Brieuc, with fishing boats anchored in the background (fig. 18). This surf and turf juxtaposition is emblematic of a region long known for both pork production and maritime traditions. While the card was produced locally in St. Brieuc, it was meant for sending across France or beyond, and the series’ title Picturesque Brittany identifies this scene as one worthy of national attention, within some would-be national pantheon of rustic vistas and folksy customs. There could be any number of reasons for this selection, but what’s most compelling about the card gastronomically is its depiction of a scene that, while traditional, nonetheless embodies an emergent alimentary paradigm. With its foraging pigs and fishing fleet, the card captures the longstanding coexistence on the Breton coast of land and sea, and of the foods they yielded. At the time, the landlocked majority of the country was having a budding love affair with seafood.[51] Thanks to new means of transporting and preserving food, while seafood and especially fresh seafood were once an exception, their inclusion in the diet was becoming if not the norm then at least a popular ideal. So Picturesque Brittany combines novelty and nostalgia in a way that would have resonated for contemporary viewers. And other cards serve up imaginative conjunctions of land and sea likely informed as well by the period’s seafood mania. Some flog a verbal-visual, land-sea pun on the homonyms “porc” (pork or pig) and “port” (port) as cards entitled Le port de Toulon or Le vieux porc de Marseille showcase a large pig with a panorama of the town’s port across its belly (fig. 19). More elaborate and more evocative still is one entitled THE SARDINE OF THE OLD PORT OF MARSEILLE (fig. 20),[52] in which a pig is saddened by an oversized, postcard-shaped image of Marseille highlighting a gargantuan fish removed from the water and suspended from the Pont Transbordeur, a massive modern bridge built in 1905 to connect the two sides of the port. Accompanying verses gloss the scene:

He cries, he moans, the old POR . . . of MARSEILLE

Seeing the SARDINE, his incomparable friend,

Pulled from the blue depths by the Pont Transbordeur

He cries, he moans, he’s sick to his stomach.[53]

Whatever forgotten local lore this card may reference, it is also an allegory of the land-sea dialogue in French geography and cuisine, for in addition to the giant sardine pulled from the deep, the pig’s salty tears flow into the watery surface where he sits, as he ponders the juncture between water and terra firma in the port, while the wise old moon—who regulates the tides that forever renegotiate boundaries between land and sea—looks down knowingly. The pig’s special connection with the sardine is suggestive, engaging notions of past and present, tradition and modernity, and reflecting back on his own fate. His identification with and sympathy for the victim is reminiscent of the close human relationship to pigs sacrificed in a traditional way, yet the shimmering surface beneath him also looks eerily like the blood-soaked floor in modern slaughterhouses (fig. 21. The role played here by the Pont Transbordeur, a brand-new local icon of modernity, also suggests the emergent regime of industrial slaughter. While the pig’s immersion in brine conjures up the traditional preservation of meat through salting, the mechanical bridge—moving the fish along as if on an assembly line—instead calls to mind new forms of preservation, notably canning, first used on a large scale for sardines, and easily accessible to French consumers.[54] And just as later American marketing would portray tuna as the “chicken of the sea,”[55] this card’s insistent identification between these two otherwise unlikely “friends” invites a suggestive vision of canned sardines as the pork of the sea—fatty, flavorful, abundant, inexpensive, and by this time readily available across France much like salted and smoked pork products had long been.

Other cards get at the relations of pigs or sardines to Mardi Gras and Lent. Some (fig. 22) show pigs looming in floats at Mardi Gras parades. In one noteworthy humorous card (fig. 23), an old woman (whether blind, senile, or just joking) seems to mistake the pig being slaughtered for a giant sardine, exclaiming that this will make for “a good Lent.”[56] Pork proscriptions at Lent call to mind other more general religious laws against pork consumption, notably the kashruth at a time when the Dreyfus Affair had provoked debate about Jews’ place within French society. And on Belle Époque pig postcards, religious difference defines identity implicitly, consolidating Frenchness by excluding otherness as a legitimate option, for across these cards the underlying assumption is that France is a country of pigs and pig eaters. The old French drinking song declares, “He’s one of us, he’s drunk his glass like the rest of us,”[57] making wine drinking the hallmark of group identity. So too for pork: whoever eats it is likewise “one of us.”[58]

Pigs provided the French with a kind of lowly common denominator. In The Painter in the Village, for example (fig. 5), the locals, notably a clog-wearing peasant and a top-hatted bourgeois, watch enthusiastically as an urban type, a bohemian artiste (complete with beret and pipe) paints a pig on the outside wall of the village charcuterie. These men, a small cross-section of the French population, are joined in a common homage to the ubiquitous pig, their gesture of gastronomic unity echoed by the suggestion of wine (that other great Gallic unifier) in the grapevine growing up the side of the building and the oak barrels holding up the muralist’s scaffold. Like so many other Belle Époque pig cards, this one is nostalgic, with both religious and gastronomic resonances. The men line up as if to take sacrament at the altar of popular art, partaking of the pig visually before consuming it physically, with the label “Charcuterie” defining the offering up of the pig’s transformed body, a humble, pragmatic, secular version of “This is my body.” And the card indulges as well in the neo-Rabelaisian enthusiasm for charcuterie and la dive bouteille[59] that pervades nascent culinary regionalism, whether in the work of self-appointed professional gourmands like Curnonsky and Rouff, or in the extraordinary proliferation of Third Republic illustrated menus.[60]

So Belle Époque Frenchmen might disagree on many things, from Dreyfus to Debussy, but they could agree on their shared passion for wine and swine. The Painter in the Village thus frames a mise en abyme not only of a common penchant for depicting pigs, but also of a national consensus around pigs and the snout-to-tail feast that they continued to offer. Yet despite its charmingly nostalgic air and celebration of an old-fashioned local charcuterie in particular, the specter of the modern food world lurks, a veritable wolf in pigskin, in the guise of the card’s sponsor. Félix Potin, the pioneering French grocery chain, which manufactured products like chocolate in its own factories, had been founded in Paris in the mid nineteenth century, spread throughout the Paris region by the Belle Époque, and was poised to expand across France after the Great War.[61] Beneath the card’s more obvious tribute to homegrown hogs and corner groceries past, there is a vision of industrial food production and supermarkets to come.

From Sacrifice to Slaughter

How do pigs become pork (and lard, bristles, blood sausage, etc.)? Belle Époque postcards put forth divergent versions of the fatal transformation. Some serve up a nostalgic vision of traditional, intimate sacrifice. Others, with a mix of excitement and dread, offer a largely anticipatory vision of slaughter through industrial production. Either way the pig dies, but the implications are very different.

Sacrificial practices reach far back and across cultures. Calves, goats, and lambs were common victims, but so too were pigs.[62] Deep in our past animals also provided real and symbolic stand ins for human sacrificial victims.[63] This connection becomes especially compelling with pigs, considered so close to humans in so many ways. Pigs are known to devour their own young, and sometimes ours as well, complicating matters further: should they eat one of us, what would it mean—and what would it make us—if we eat them in turn? This intertwining of mutual consumption flirts with human cannibalism and, understandably, troubled our ancestors.[64] There is ample folklore, legend, and historical documentation likening pig and human flesh, from stories about pork replacing human meat in certain ancient dishes, like Mexican pozole;[65] to the tale of St. Nicolas resuscitating three boys cut up and preserved in salt; to accounts of medieval brigands selling pieces of their human victims as pig parts.[66] Such varied and abundant evidence leads Pastoureau to conclude, “Eating pork means more or less being a cannibal.”[67]

The French peasant’s tue-cochon or pig killing was highly codified, with rules, for example, about spilling and collecting blood and transforming it into boudins or blood sausage. It was a time of renewal and reaffirmation, accompanied by extensive culinary rituals, linked to a web of other traditional practices, beliefs, and religious holidays, and in these ways reminiscent of earlier religious sacrifices, even traditional cannibalism. Far from gratuitous cruelty, cannibalism in traditional societies was built upon webs of meaningful relations and deep-rooted beliefs.[68] And the sacrificial tue-cochon resembles cannibalistic ritual, not just in the elaborate ceremonial surrounding both, but also in its broader psychological, philosophical, and spiritual underpinnings.[69] To be sure, there are economic and social dimensions to consider in the tue-cochon, which yielded sustenance for the whole year while affirming family and community ties. But on a deeper level, the whole complex of ritual, ceremony, belief, and custom accompanying the event also mitigated its violence and, as in traditional cannibalism, assuaged participants’ conscience about killing and consuming their counterpart—in this case a porcine “cousin.”[70]

Before the advent of modern industrial pork production, the traditional practices of the tue-cochon had endured, largely unchanged and a fixture of peasant life, for a millenium.[71] Despite endless local variations, the broad lines of the sacrifice were consistent: immobilizing the pig, slitting its throat, collecting its blood, removing its bristles, cutting it open and apart, preparing all sorts of dishes and charcuterie from the carcass, sharing some of this in a carnivorous feast called la Saint-Cochon, and consuming the rest of the preserved meat and lard more sparingly throughout the year. Kinship and community ties determined who could participate, and in what capacity, during the event and ensuing feast. Tasks split along gender lines, with men responsible for killing and butchering, and women for preparing the meat. Blood was a central motif, and the subject of multiple proscriptions, notably involving women.[72] Those in their menstrual period were prohibited from participating. Stirring the blood collected from the pig’s throat—so premature coagulation wouldn’t ruin the boudins—was such a critical operation that it could only be entrusted to women safely into menopause. Scheduling the tue-cochon was tricky as well. It could not take place on religious holidays, nor on the Sabbath day of rest, nor on Friday because eating flesh from warm-blooded animals on the day of Jesus’s sacrifice was prohibited.[73] In addition, it could only happen when the local saigneur was available. Responsible for killing the pig, and especially for administering the fatal blow, the saigneur was a deeply respected member of the community, the central figure of this crucial event in the peasant calendar.

In France as in much of Europe, pigs were slaughtered between December and February, with cold weather providing better conditions for keeping fresh meat, some to be consumed soon, but the rest preserved through smoking and salting, to last through the seasons. The tue-cochon was a high point in the year for the family, on the farm, and in the village. Often timed to just precede Christmas or carnival, it provided meat for those occasions. Like a holiday in itself, the feast of la Saint-Cochon was a carnivalesque event with a name patterned on religious saints’ days. The consumption of the remaining pork products through the year marked other key moments in the liturgical calendar, like the eating of a ham on Christmas Eve. And on the morning of the tue-cochon, to mark the completion of the annual cycle, the last meat from the previous year would be served for breakfast. In some regions this was a fat sausage called a Jésus, the name pointing to the underlying religious dimension in this process of renewal through sacrifice.[74]

As such practices—and the reassurance they provided—were beginning to fade into the past, Belle Époque pig postcards would record, commemorate, and celebrate them. Many focus in particular on the time-honored ceremonial of the tue-cochon. Some cards, including humorous ones, get at the gravity of the creature’s sacrifice by likening it to human execution, invoking the title of Victor Hugo’s novel The Last Day of a Condemned Man or, in a carnivalesque turn (fig. 24), showing a pig sacrificing a man (the title reads, The World Upside-down).[75] And the tue-cochon is so much a part of daily life that it may figure in the card’s handwritten inscription, instead of in its published text or image. One such card (fig. 25), sent in 1905, offers a comical image of four particularly round pigs bounding across a meadow as the sun rises, with four-leaf clover motifs in both upper corners—a sweet, banal, happy image, like countless pig-themed good luck cards. But in a note written across the card’s face, the sender remarks, “This is appropriate for the occasion, we killed him yesterday, at ‘Las Serres.’ Today the salt pork is being prepared and will be ready in September.”[76] The sender writes in correct, standard French, with elevated diction for this humble context. It is not what one would expect from a farmer, particularly at this time, and, apparently the card circulated within a family of well-to-do wine and armagnac merchants. They lived in the town of Auch, in the Gers department, but had a nearby farm (called “Las Serres”), and the card was sent by one relative to another living in the city of Orléans, in the Loire Valley.[77] Tellingly, even among the members of this urban, bourgeois family, there is no hesitation, squeamishness, or avoidance in talking about the fate of this pig (“we killed him”), and the use of the direct object pronoun “him” without any explicit antecedent shows that both parties to the communication knew the animal. Despite the modern postcard medium used to deliver the message, this all remains within the traditional realm of food produced locally, raised with care, and slaughtered and consumed with respect, dignity, and gratitude, within a tight circle of family, friends, and neighbors. Clearly, news of the pig’s sacrifice was considered important, worthy of sharing with those in that circle who couldn’t be present for the occasion.

The tue-cochon was a communal event, and in one characteristic card a group of Breton peasants (presumably family members, probably also neighbors) gather round to participate and watch, with great solemnity and sense of purpose (fig. 26). In the middle of the farmyard, in front of a traditional-looking, thatch-roofed farmhouse, the pig lies on a board atop a barrel. Two men and one older woman hold down its rear legs and midsection as the saigneur attends to the head and neck, and especially to the all-important cut he’s made there, while another old woman collects the resulting blood in a bucket below. The pig’s sacrifice has brought all else on the farm to a halt: one woman pauses in the middle of her knitting, the children have been brought here to see what’s happening, and a dog lurks, hopeful for a scrap. All watch intently, focused on the saigneur, and on his critical task. Unlike the studio-produced card IN BRITTANY Peasant from the Huelgoat and Carhaix area—the three Friends (fig. 7), this scene was clearly photographed in situ, and the onlookers’ garb, from their rumpled, soiled clothes down to their muddy clogs, seems genuine. Yet, it’s hard to tell for sure from the image if the blood is still flowing (it seems not), and certainly it would have been easier to shoot the photo with a dead, rather than a dying, flailing pig. So, perhaps this is not the scene itself, but a recreation after the fact, like a police reenactment of a crime—not exactly the real thing, though informed nonetheless by a keen desire to get it right and preserve the moment for posterity. And then there is the card’s title, nearly hidden in the thatched roof: Life in the countryside – A sacrifice.[78] The designation Life in the countryside, like Picturesque Brittany in fig. 18, points to certain types of scenes and customs to be recorded and remembered as part of the collective cultural heritage. The tue-cochon in particular (“the sacrifice”) exemplifies the larger category of rural existence (“life in the countryside”), and is subjected to an ethnographic gaze eager to capture this colorful way of life before it fades or vanishes.

In their drive to frame some elusive authenticity, ethnographically-minded tue-cochon cards like this one get up close to show the sacrifice unfolding in vivid photographic detail. Some individual cards focus on the most critical moment: the mortal blow and saignée or bleeding of the animal. There are also series featuring the stages of the sacrifice on separate cards. One series entitled Play in one act—THE DEATH OF THE PIG highlights such tableaux as “In the executioner’s hands, the fatal moment” (the saigneur slitting the pig’s throat, while his assistant helps hold the animal down), “The last grooming” (with them singeing off the bristles), or “The body on display before becoming andouilles” (as the men stand beside the carcass that’s suspended from a ladder and split down the middle, exposing its innards) (fig. 27). In short, such cards deal frankly with the death, dismemberment, blood, and guts of the sacrificial victim.

While a fascinating and revealing phenomenon, the rural tue-cochon was by far not the only means of pork production before widespread industrialization. From the Middle Ages onward, the slaughtering of hogs in towns and cities represented a significant economic activity and constituted an intermediate point between peasants’ highly ritualized, seasonal harvesting, and rationalized modern industrial production. Compared to later industrial processing, this urban butchering remained relatively small-scale and, because of limited options for transportation, tied to both the region for stock and local community for customers. But it also differed from peasant practices in the more substantial volume of meat and lard generated, possibility of nearly year-round production, obedience to practical, commercial imperatives, and, therefore, general lack of larger symbolic and spiritual considerations. And unlike the respected rural saigneur, the urban butcher, while often wealthy and powerful, was a suspect figure whose reputation for violence and cruelty survives in modern fictional characters like the bloodthirsty, anthropophagic butcher in the film Delicatessen (dir. Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro, 1991).

By the end of the eighteenth century, moreover, the practice of butchering livestock in city streets and alleyways had become suspect as well. In growing agglomerations the noise, stench, and gore of urban butchering came to be seen increasingly as offensive and unhygienic, needing to be controlled, contained, regulated, and, ideally, relegated to closed, dedicated facilities outside the center—a development exemplified by the opening of the so-called Cité du sang (City of blood), the slaughterhouse complex at La Villette, in 1867.[79] The modern slaughterhouse was thus born largely out of hygienic concerns, but there were aesthetic, moral, and philosophical dimensions to this evolution as well.[80] A new sensibility was emerging, which also informed the replacement of cities’ overflowing old churchyard cemeteries with large new modern nécropoles on the periphery, like the Père-Lachaise. Death, both human and animal, was exiled from the city center. It was a key first step toward the radical exclusion of death from the realm of the living, in our sanitized modern world of vacuum-packed pork roasts, hospitals, and even modern military technologies, from machine guns to drones that isolate us ever more from the enemy being killed.[81]

The modern meatpacking industry, in particular, is a marvel of collective denial. Noélie Vialles’s excellent study of slaughterhouses in the Adour region[82] exposes how we rely today upon a complex system of avoidances to distance ourselves from the horrors inside slaughterhouses—a far cry from the tue-cochon as a communal event and highpoint of the peasant calendar—or even from the once-common spectacle of butchers slaughtering on city streets. It is telling that, unlike the respected traditional saigneur, or the dreaded urban butcher, those responsible for killing livestock today are relegated to virtual nonexistence, their work invisible, anonymous, and designated only by euphemism (in the United States, this work often devolves to illegal aliens, at the margins of American society).

During the Belle Époque, French pork production was split between a past and a future that coexisted, however incongruously, in the present. On the one hand, there was traditional sacrifice that yielded ever less pork for a rural population itself in decline. Yet as we see in contemporary postcards, the tue-cochon held a grip on the French imagination disproportionate to the actual volume of food that it provided. On the other hand, France was already experiencing the emergence of what Pastoureau calls “true industrial pork raising.”[83] And many postcards deal in one way or another with the implications of the large-scale slaughter carried out by this nascent pork industry. Cards can appear giddy about the novelty but profoundly uneasy as well. Postcard publishers, with their stock tue-cochon and “last day of a condemned man” views and series, were used to depicting pigs’ traditional transformation into pork, but puzzled over how to handle things when the killing was divorced from the sacrificial context that had long surrounded a pig’s death and given it meaning, mitigating the accompanying violence. Some postcards get at this by recording the bleak, carceral spaces of modern slaughterhouses, bearing witness to this unsettling new state of affairs. Certain of these cards feature the facilities’ forbidding exteriors, with walls, gates, and guards shutting out both curious passersby and viewers like ourselves.[84] Others do take us inside, but just to glimpse what’s there. One photographic card, “LYON-VAISE.—The Slaughterhouses. The bleeding of the pigs” (fig. 21) shows a large workspace, illuminated by harsh electric lights, where rows of pig carcasses hang from their hind legs, dripping onto a blood-soaked floor. This is a striking departure from rustic “sacrifice” cards that foreground the heroic struggle between a single pig and a skillful saigneur and focus on the inevitable result, the pig’s demise. Here, in contrast, the card emphasizes the institutional setting, with its vats, hoists, and metal framework for suspending the carcasses—an assembly, or rather disassembly line. The slaughterhouse workers, seen from afar like the many pigs they process, seem but tiny cogs in a vast, industrial machine. Tellingly, cards like this lack the most salient feature of tue-cochon images: they don’t show pigs dying, nor dead pigs up close. Indeed the “LYON-VAISE” card exemplifies the fundamental shift in perspective that was happening at the time: all is seen from a distance, as if the workers and the whole complex of the slaughterhouse were shrinking into oblivion, fading from sight as from public consciousness. It is a critical step away from the forthrightness of traditional sacrifice, and toward the regime of avoidance and anonymity that for Vialles characterizes our relationship to modern slaughter.

Other types of pig postcards utilize different strategies for creating an effective distance from slaughter’s disturbing realities. While photographic, documentary cards use physical barriers or physical distance, illustrated comic cards rely instead upon humor and whimsy to provide a reassuring sense of detachment. In one such card (fig. 28), sent from Salon-de-Provence to Apt in 1905, an elegant couple approaches a store whose sign reads “AUTOMATIC CHARCUTERIE: HERE WE DO ALL SORTS OF PIGGY THINGS,”[85] the word play on “cochonneries” in the original French alluding to both inferior goods produced there and off-color jokes woven into the accompanying text. Out front, the old charcutier and his young male and female clerks demonstrate a fanciful Machine-Cochon, a miniature pork processing plant where a squealing pig disappears into a funnel-shaped orifice, and finished products stream out the other end. As the charcutier declares, in the first of five comic stanzas in rhyming couplets,

This evening we’re showing

The Machine-Cochon.

The pig enters, alive as can be,

And leaves as charcuterie.[86]

Press one button for ham, he explains, another for pâté, another for hard sausage. Andouille and boudin come out different-sized tubes. As if this weren’t all magical enough, should you find the preparations too salty, run the machine backwards and the pig comes out again, alive. And while ostensibly still about charcuterie, the concluding stanza turns risqué:

So enter, Sir, Madam,

Take advantage of my deals.

If you’d like a hard sausage,

Ask my salesman,

And for stuffed tongue,

My saleslady’s the one.[87]

Customers long for the handsome clerk’s “sausage” and his pretty female counterpart’s tongue. Ending on this ribald note, the card’s humorous verse injects a dose of gauloiserie to divert attention from the horror of mechanized slaughter. So, too, the whimsical technology works to deny slaughter’s reality, as well as its finality, for with this contraption the pig’s death is reassuringly reversible. And the venue is just as fanciful, taking pork processing out of a closed, institutional, industrial setting, and locating it outside, in the open, on a charmingly tree-lined, provincial street where well-dressed couples stroll and visit traditional local stores like this charcuterie. As in the Félix Potin Painter in the Village card (fig. 5), a contrived, nostalgic scenario masks or at least distracts us from the upheavals of the rapidly-evolving modern food industry.

What about the bourgeois consumers’ yearning for human flesh (“sausage” and tongue), conflated with that of the processed pig? Intriguingly, within a context evoking industrial pork production, there is also this intimation of cannibalism.[88] Taking the theme further, one chromo shows an innocent young pig that inadvertently eats his father’s remains by sampling an internationally-marketed brand of lard produced by N.K. Fairbank & Company of Chicago (fig. 29). The little porker, wearing fancy pajamas and a bib sporting the brand’s slogan, “ABSOLUTE PURITY,” takes a tub from atop a barrel marked “REFINED LARD,” and licks the contents enthusiastically. His horrorstruck mother sticks her frilly-bonneted head in the window and cries, “Stop, you unfortunate thing, that’s YOUR FATHER’S FAT!!!!!”[89] The foregrounded ears of corn are a recurrent motif in the company’s advertising from this period and promote the virtues of lard produced from corn-fed, rather than slop-fed pigs. But taken to an extreme, as in another advertising card’s slogan, “N.K. FAIRBANK & CO’S LARD is Pure CORN JUICE Boiled down,”[90] this emphasis on corn makes us wonder. Is the lard made of pig or corn? Is it animal or vegetable? The mother’s oddly bovine hooves are also disconcerting: have other animals’ parts been mixed in the lard? What of the anthropomorphic hogs whose relative’s lard has been rendered? Are we too eating our own when we consume animals who resemble us? Despite the slogans, how “refined” is this lard, how “absolute” its purity? Unwittingly, this advertisement recalls stories circulating at the time about slaughterhouse workers fallen into vats and rendered into so-called “pure” lard—most famously in The Jungle, Upton Sinclair’s influential indictment of the Chicago meatpacking industry (published in 1906, and translated almost immediately into French and 16 other languages).[91] Both the mother pig’s exclamation and subtler visual cues make us suspect that we are eating something other than what the manufacturer claims, and perhaps something we shouldn’t be eating at all. Far from traditional, intentional cannibalism in which the participants know what they are eating and why, modern industrial meat production had brought about a new form of what may be called “accidental” cannibalism. The potential for unpleasant, even dangerous surprises lurking in meat (and, for that matter, all food products) became all the greater with the nationalization and eventual globalization of food production, progressively dissociating consumers from food sources. Fairbank lard, made in Chicago but marketed abroad, provides a suggestive early example. The little pig plays the unsuspecting consumer, unaware of industrial food products’ provenance. And the mother’s desperate cry conjures up a whole panoply of modern food fears focused on this thorny issue of origins. Such fears would eventually lead to a new ideal of transparency in the supply chain, from farm to table, or, what French meat producers in the wake of the mad cow scare of 1996 began vaunting in their advertising as la traçabilité, or traceability.[92]

While the Fairbanks postcard draws attention to the death of the pig as a necessary step to obtain meat products, a 1919 chromo promoting Good sausages from the PRODIGAL PIG (fig. 30)[93] features a very alive pig slashing himself into neat sausage rounds, like a streamlined version of the earlier Machine-Cochon (fig. 28). The vivid colors, bright illumination, caricatural mode, and snappy advertising copy all suggest forced light-heartedness in an attempt to obscure grisly subject matter with humor. This advertisement for mass-produced sausage from Auvergne, with its familiar claim of “purity” to allay fears about processed meat content, offers a tellingly obfuscatory vision of industrial meat production. In contrast to rationalized slaughter’s ruthless logic, the image defies the laws of physics and biology: the bisected pig remains standing; it performs deft knife work without hands; like the three small sausage rounds, the heavy blade seems suspended in midair; and the large platform-like disks have no explicable provenance. Rather than real blood and innards displayed in tue-cochon cards, the sausage rounds and pig’s insides are made of the same composite material, a bright, festive shade of red interspersed with gold and silver flecks, like a colorful confetti mix. All the slicing is done, as if by magic, without bloodshed or apparent pain or suffering for the animal. The image’s graphic qualities, particularly its dark outlines, recall Japanese prints so influential in French art circles over the preceding half century, and the pig’s self-immolation is reminiscent of Japanese seppuku (also known informally as hara-kiri), a custom that already fascinated western observers at the time.[94] As the jolly pig becomes a brave samurai, we glimpse two emblematically divergent perspectives: his death gets redeemed as an honorable, meaningful one, with seppuku standing in for the sacrificial ritual of the tue-cochon; or his exotic cultural practice casts him as a foreigner, undoing the period’s pervasive identification of pigs with Frenchman, and figuring instead the growing alienation of the French from the pigs they ate, as from the ways the meat was processed.

Within the corpus of Belle Époque pig postcards, there are many examples of pigs smoking pipes or cigars, and many more still of pigs surrounded by ice and snow—skating on frozen ponds, frolicking in wintry landscapes, and so forth. Why? To some extent, pigs smoking can be explained by their widespread anthropomorphization on postcards, and cold can be explained by the seasonality of both the tue-cochon and of postcard publishing, since so many pig cards marked winter holidays, especially New Year’s, but also carnival and the feast of Saint Antoine. But on another level, postcards like these, along with the abundant maritime-themed cards we’ve already encountered, point to the shift in preservation techniques within the broader transition underway from local, traditional to modern, industrialized food production, and specifically from preserving meat with smoke and salt, to preserving through refrigeration, a new technology evolving rapidly at the time. In this connection, wintry pig postcards with no explicit link to winter holidays are of particular interest, as they associate pigs with cold itself, rather than with specific events during the cold season. In one such card (fig. 31), postmarked 1901, little pigs in a circle dance fervently on a snowy field around a large snow pig, its arms outstretched and a demoniacal expression on its face, like a malevolent idol in a cult-like adoration scene. Maybe this is just the illustrator’s fantasy, but in the context of the period it’s tempting to see more. A strange energy circulates here, in the almost unnatural light illuminating the composition and the zeal moving the pigs, which whirl together like a wheel, fan, or turbine spinning on a central axis, while the mysteriously frosty snow pig suggests experiments at the time with deep freezing, storing, and transporting frozen animal carcasses. The 1900 Paris World’s Fair had staged a huge, public tribute to electrical power, notably in its massive (and massively popular) Palace of Electricity, surmounted by a six meter high statue of The Fairy of Electricity[95] with similarly outstretched arms, all of which produced the greatest effect at night, when floodlit by electric lamps. Perhaps, then, this card offers a humble response to The Fairy of Electricity, an homage to artificial cold like the far more grandiose Parisian homage to artificial light, and maybe even an ironic take on the public’s wild enthusiasm for new technological marvels. On another equally evocative card (fig. 32), an elegantly-dressed belle sits upon a strangely-constituted snow pig, its body sheathed in a sort of sausage casing, like some processed frozen pork product. The pig smiles as the woman’s hand rests tenderly but possessively upon its back with index finger outstretched, as if she’s emphasizing, “this is mine” (though a snow man in the background ogles her, she picks the pig instead). Her impeccably fashionable attire and knowing gaze toward us, the card’s eager viewers, signal her connections to a burgeoning commercial culture. Rather than a peasant woman’s maternal love for her piglet, this card highlights a well-heeled consumer’s prerogative to choose what she wants: a premonitory vision of supermarket shopping as it would evolve in the decades ahead.

Perhaps the incongruity of such postcards also figures a noteworthy historical lag, since France was a leader in early refrigeration technology, but slow to adopt it for actual food industry use. In France, refrigeration remained less a part of daily reality than of an imaginary of the period, and specifically of what Capatti calls a “polar obsession,” that we glimpse in fanciful images like these.[96] Meanwhile other modern conveniences and conveyances were becoming ever more a part of daily life and of the food supply. Trains, bicycles, automobiles, and of course flying machines loomed especially large as hallmarks of modernity.

When Pigs Fly

During the pig’s sacrifice at the center of Robert Marteau’s short novel The Day the Pig Was Killed, set in the years following World War II, an airplane still provides a jarring contrast, much as it would have a half century earlier: an incursion of the modern world into the traditional scene of the tue-cochon at the farm.[97] Belle Époque postcards offer many such juxtapositions. All sorts of encounters occur between pigs and various manifestations of the modern world, like the Old Pig of Marseille confronting the Pont Transbordeur (fig. 20), the Fairbank piglet eating industrially processed lard (fig. 29), or unsuspecting swine getting fed into fanciful but suggestive automatic butchering machines (fig. 28). In postcards, modernity often takes the form of new-fangled transportation, like automobiles, bicycles, or trains, with various images of pigs run over on road or rail. For example, The Run-Over Pig (fig. 33) is one of the many popular Legend of Saint-Saulge postcards featuring colorful locals, speaking in patois, encountering various aspects of the modern world: the legal and electoral systems, advertising, posters, streetlighting, telephones, or, in this instance, trains.[98] As the pig gets sliced in half by a locomotive’s front wheel, a peasant grieves in patois, cursing “th’ nasty invention” and wondering what she’ll become without her “poor l’il porker.”[99] Further underscoring the close bond between owner and pig, the creature looks beseechingly at her in its last moment, like a faithful dog, while the locomotive chops up the carcass with the expediency of the Machine-Cochon vaunted elsewhere (fig. 28). In another postcard (fig. 34), postmarked 1908, a chauffeur-driven car with three well-dressed passengers hits a pig on a country road, and the characters react with varying degrees of composure: men look on calmly, women throw up their arms in dismay, and the victim cries, predictably, like a stuck pig, as the vehicle’s rear wheel strikes him. The title, An Obstacle, recalls one of the period’s best-known advertising slogans, “The Michelin Tire drinks up obstacles,”[100] though here rather than bits of metal or glass the tire would need, less plausibly still, to swallow the whole hog. Presumably, these forward-thinking automobilists have driven into the countryside to reconnect on their own comfortable terms with the terroir. But their desire to avoid such rustic unpleasantries as the slaughtering of hogs gets thwarted by the obtrusive “obstacle” of the pig’s body, like some kind of alimentary return of the repressed.

Such encounters between pigs and cars or trains are plausible and probably happened with some frequency, but other cards venture instead into the phantasmic realm of pigs riding bicycles, driving cars, or, most improbable of all, flying. Postcard artists exploited the aeronautic theme from every imaginable angle, spinning off pigs with wings, pigs piloting hot air balloons or primitive planes, pig-carrying zeppelins using champagne power for proto-jet propulsion, piggy banks with propellers transporting human passengers, and normally ponderous pigs transformed into lighter-than-air craft. At least on Belle Époque postcards, modernity is when pigs fly, figuring in the most emphatic way possible the development and expansion of transportation technologies that, through their ability to move foodstuffs like pork products ever further and faster, were revolutionizing the food industry.