The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut

September 11 – November 30, 2014

Catalogue:

Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901

Edited by Martina Droth, Jason Edwards, and Michael Hatt

New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

448 pp.; 303 color illustrations; biographies, bibliography, index.

$80.00

ISBN: 978-0-300-20803-0

For modernists, the phrase “Victorian sculpture” likely conjures images of decaying monuments with historicized figures, or sentimental statuettes bordering on domestic kitsch. Art history has not helped this perception, as exemplified by the words of H. W. Janson, writing about sculpture produced in England during the reign of Victoria: “There can be no doubt that the distinctive achievements of these decades in architecture, painting, and the applied arts have no counterpart in sculpture. There was a real dearth of sculptural talent.”[1] Instead, Janson reserved his praise for later works known as New Sculpture because of their visual associations with Auguste Rodin and thus their modernist tendencies, a paradigm further reinforced at the time by the scholarship of Susan Beattie.[2] Benedict Read was the only art historian of their day who praised the sculptural accomplishments of Victorian artists.[3] But his encyclopedic presentation of individuals and public monuments ultimately left scholars with gaps in their understanding as to why Victorian sculpture was so ubiquitous, and how it ranged in scale and media from medals and coins to monumental friezes and statues. Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901 at the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA) was the first large-scale exhibition to address these questions. Curated by Martina Droth, Jason Edwards, and Michael Hatt, these scholars have published in recent years a number of revised ideas about nineteenth century British sculpture, from design and materiality to display and gender issues.[4] Their exhibition, then, asked the viewer to rethink his/her assumptions about what defines sculpture and to reconsider the object over its maker. Rather than present a “greatest hits” of artists and works, or argue that sculpture fits into outdated stylistic categories from Neoclassicism to Realism, their emphasis was on sculpture-as-object in numerous media and sculpture’s relationship to production, display, and politics. They brought together 134 works for this installation, many of which were simply breathtaking and exemplified the highly skilled craftsmanship of their time.

In the entrance foyer of the YCBA the viewer encountered a preview of the exhibition in the form of a large ceramic elephant, modeled by Thomas Longmore and John Hénk and produced by Minton and Co., and first exhibited at the 1889 Exposition Universelle (fig. 1). The same work also appears on the cover of the exhibition catalogue, reinforcing its importance in the exhibition. This choice was admittedly unexpected, but this was the curatorial mission: to reconsider works that might not typically be considered sculpture because of their materiality, display, and political significance. Measuring 84 inches (213.4 centimeters) in height and standing on a pedestal, the majolica ceramic elephant forced the viewer’s engagement with its black-eyes, white tusks, swaying trunk, and exotic glazed colors. The Elephant reveals a high degree of craftsmanship that demonstrates the successful union of man and industry, but it also has a deeper meaning. Displayed as part of a cultural parade, its empty howdah decorated in Mughal textile designs and awaiting a royal occupant, the tamed elephant represents the jewel in Victoria’s crown: India and all its riches.[5] This work in the foyer thus foreshadowed others in the galleries of Sculpture Victorious: masterpieces of human and industrial design, and socio-political symbols of the British Empire.

The exhibition was located in the second floor galleries. The works on display were somewhat chronological in order, with one or more key works placed in the center of each bay to lead the viewer through the century, although this arrangement worked better in theory than reality and probably was not necessary. At the entrance the large wall text to the left, in white letters on a red wall, informed the visitor that this show was less about Queen Victoria and more about how sculpture during her reign was a form of democracy and national pride, produced in varying scales from coins with the monarch’s face to monumental sculptures of her allegorical body.[6] More importantly, during her reign from 1837 to 1901, Britain experienced an age of invention, when handcrafted talent and new technologies combined to create sculptural objects that could not have been made in the past. Despite this negation of Victoria’s importance to the exhibition, the opening presented numerous images of the queen, notably two marble busts. The first emphasized the young monarch’s beauty and innocence in a bust by Francis Chantrey, designed in 1840, while the second just beyond it quickly shifted the viewer’s attention to an oversized, elderly queen, designed in 1887–89 by Alfred Gilbert in honor of her Golden Jubilee. Baroque-style handling in the stone carving, particularly in the ugly details of the aging monarch’s face and thick trunk of a neck, gave this figure more character and depth than her predecessor, whose idealized image symbolized the dawning of a new age. Displayed in vitrines to the left and along the wall were miniature, mass-produced representations of Victoria available to middle-class consumers, derived from official images of the monarch such as the busts. One amazing feat of artistic, technical ingenuity, developed early in Victoria’s lifetime, was the sculpture-reduction machine. Prototypes had been designed and utilized by James Watt and John Isaac Hawkins, but by 1828 Benjamin Cheverton had launched the most commercially viable machine.[7] His replica of Chantrey’s bust of the queen, in ivory on a stone socle, measures about 7 inches and dates from 1842 (fig. 2). The carving arguably reveals its mechanical origins, but the delicacy in its handling and details is still extraordinary. This work was grouped with an 1862 Parian porcelain figurine produced by Minton after a marble bust by Carlo, Baron Marochetti, and Edward Onslow Ford’s 1898 bronze bust derived from a life-sized monument in Manchester.

To the right of the busts in vitrines and wall cases were a sparkling array of medals, coins, badges, and jewels, also with depictions of the queen. The 1862 First Class Badge of the Royal Order of Victoria and Albert is significant in that it was designed exclusively for women from European royal families and a select few women in Victoria’s court, and intended as a memorial to Prince Albert following his death in 1861 (fig. 3). Normally worn on a white moiré ribbon, the badge depicts double-portrait profiles of the queen and consort carved by the Rome-based cameo maker Tommaso Saulini, taken from William Wyon’s 1851 Great Exhibition prize medal. The dazzling setting in gold, silver, pastes, diamonds, and emeralds was designed by the jewelry maker R. and S. Garrard and Co. Among the medals on display was one large work celebrating Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, depicting double-portrait profiles of the older queen shadowed by her younger self, echoing the passage of time and maturing of the empire, and mirroring the effect of the two life-sized busts nearby (fig. 4). Pairing the two busts with miniaturized replicas and images of the monarch in various media succeeded in demonstrating how appropriation and reproduction were critical to the democratic dissemination of Victoria’s image. Although some works were royal commissions, such as the Chantrey bust or the Saulini/Garrard badge, others were mass-produced by manufacturers but taken directly from commissioned works, thus allowing for the commercialized propagation of sanctioned representations of the monarch. Small sculptural works in multiple media also gave people the opportunity to symbolically hold the monarch in their hands and feel they were part of her global empire.

Also in this opening section was a tall statue of Saher de Quincy, Earl of Winchester, 1848–53, normally seen with seventeen other historic statues in niches twenty-five feet above the Chamber of the House of Lords. Initially, I assumed it was a statue of Albert in historic dress, because of its proximity to Victoria, and this error on my part led to an awareness that Albert, with the exception of the badges and medals, was largely missing from the exhibition. His noteworthy absence in wall texts and object labels was surprising, considering he was an advocate of industry and design, and a connoisseur and collector of paintings and sculptures. However, the 2010 show Victoria & Albert: Art & Love at Buckingham Palace presented this topic well with a stellar exhibition, so perhaps the curators of Sculpture Victorious felt it was unnecessary to address this further.[8] Winchester was one of the barons who secured the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215 and thus his image serves as an iconographic reference to the long history of the monarchy and Parliament. The sculpture is another marvel of Victorian technology, made from zinc electroplate with copper and gilding, and the design of his chainmail armor simply was amazing when examined closely.[9] His medievalism, however, contrasted sharply with the images of Victoria in white marble and other related media, and I wondered if Winchester would have been better appreciated in the entrance near the Minton Elephant as an alternative example of sculptural materiality, technology, and politics.

Winchester also could have been a focal point of the next section, “Sculpture and National History,” emphasizing Britain’s medieval past. The curators noted: “The political role of sculpture and its place in public life is nowhere more evident than in sculptors’ extensive engagement with national history. . . . Sculpture thereby refashioned the present in the guise of the past and the past for the purposes of the present.”[10] The focal point in this gallery was the Eglinton Trophy, 1843, a work crafted in silver and silver-plated copper that glimmered in its vitrine (fig. 5). The trophy was a gift to the 13th Earl of Eglinton for hosting in 1839 one of the most lavish ‘Medieval Times’-themed historical jousts and banquets at his country seat of Ayrshire. The story behind this work may seem laughable today because of its intentionally proud historicism, something an art historian such as Janson would have abhorred, but the exquisitely made trophy entranced the viewer. Walking around the trophy and examining it from multiple angles, one could not help but appreciate the skillful craftsmanship and details in the figures and architectural design, such as in one part where a young woman in medieval dress gazes down lovingly from the winding staircase toward the knight who reciprocates her feelings, a visual allusion to the Victorian reimagining of Arthurian chivalrous love. Another fascinating work in this bay was a copper electrotype of Queen Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603). Cast from her stone effigy in Westminster Abbey, then transformed into metal by Elkington and Co., the figure was intentionally repositioned upright to make the work a portrait sculpture (fig. 6). This was one of a series of historical figures made in this manner and commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery with the intent both to display historical monarchs in that museum and to preserve their decaying monuments with replicas made from a new technology. Seen in this exhibition as an example of art and industrial innovation, the subject also reveals its political nature, as the powerful Tudor queen at the time was appropriated as an icon for Victoria and her reign as a new Elizabethan age.

The fact that the electrotype Elizabeth was intended for display reinforces the curatorial interest in the ubiquitous presence of sculpture in the lives of the Victorians. Whether seen in the form of large public outdoor monuments or miniature replicas, figurative sculpture was prolific in nineteenth-century Britain. This was perhaps no more apparent than in the 1851 Great Exhibition, where sculptures and manufactured sculptural objects based on these marbles and bronzes were the only art works on display, because of their co-existence as hand-crafted and industrially-made objects.[11] The next section in the exhibition emphasized the 1851 world’s fair for its important role in the display of sculpture, but also showed noteworthy sculptural works shown at other expositions in London and Paris over the course of the Victorian era. For instance, seen in this bay was the beautiful, life-sized Peacock designed by Paul Comolera and produced by Minton in 1873 as one of a dozen (fig. 7). Made sixteen years before the Minton Elephant, the Peacock demonstrates the historicist interest in modern reproductions of Renaissance majolica, but also relates to the rising Aesthetic Movement with its love of stuffed peacocks and their feathers decorating stairwells throughout the homes of artists and the upper middle classes in London.

On display elsewhere in this bay was another technological innovation that won top prizes at the Great Exhibition: Parian ware, a form of ceramics developed in the 1840s in which statuettes were crafted with the texture and appearance of marble. John Gibson’s Narcissus was one of the earliest Parian figurines to be mass-produced by Copeland and Garrett, the credited inventors of Parian ware (fig. 8). Gibson’s life-sized Narcissus was his Royal Academy diploma work, first exhibited publicly in 1838. It was praised by the press as one of the best sculptures on display that year, one critic writing that “nothing can be more graceful than the general contour; while the flesh seems as if it would yield to the touch.”[12] The appreciation of the sculpture for its combination of classical form and naturalism, as well as its appeal to sentiment in order to evoke an aesthetic response, made it an appropriate work to select for a miniature replica that could be brought to the masses. These statuettes were significant for collectors at that time because they represented the latest innovation in the ceramics industry, and their very existence as marble-like works enhanced their appeal as fine art objects. Numerous reports were published at the time in journals such as The Art-Union, explaining the process in depth.[13] The dissemination of the Parian Narcissus by lottery through the Art Union of London also was seen as a tool to educate the masses about art, thanks to the collaboration of an important sculptor with a manufacturer. These figurines, crafted after ancient and modern works, populated mantelpieces throughout the homes of the middle classes, and were actively collected by Victoria and Albert as well.

One of the more creative installations in the exhibition also appeared in this section, and it aptly demonstrated how display was critical to the reception of Victorian sculpture. This was the installation of three enslaved female figures, each of whom appeared remarkably different, but whose grouping offered viewers an opportunity to think about issues of gender, race, and colonialism during the nineteenth century (fig. 9). The best known work in this trio was Hiram Powers’s Greek Slave, and it was grouped with a reduction in marble of Harriet Hosmer’s Zenobia in Chains and John Bell’s bronze American Slave, a pathos-driven work that outshone the others. Powers’s statue was the great success story of the 1851 Great Exhibition, its allusion to American slavery apparent to most viewers (fig. 10). Although made by an American sculptor working in Rome, potentially challenging its inclusion in this exhibition for nationalist reasons, its successful display in London led to numerous British-made reproductions in Parian ware, textiles, photographs, prints, illustrated books, and other media, a selection of which were on display nearby as well.[14] In Zenobia, Hosmer depicted the third-century Syrian queen as a regal, classical figure imprisoned in shackles (fig. 11). The first version, measuring nearly seven feet in height, had been lost for many years, but was eventually rediscovered and is now in the collection of the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California. Although this work also was by an American sculptor based in Rome, it premiered in London at the 1862 International Exhibition, as did an electrotype version of Bell’s American Slave. Cast in smooth, polished bronze with silver chains, this version of Bell’s sculpture in the installation offered a sharp contrast to the austerity of the white marbles (fig. 12). The head of The American Slave bears some resemblance to the 1851 Bust of an African Woman by Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier, a replica of which Victoria and Albert themselves owned, but as Hatt argues in his catalogue essay for this work, Bell’s sculpture was intended to be a direct response to Powers’s statue. First exhibited in plaster at the 1853 Royal Academy, his statue directly addressed the issue of slavery in America with a powerful, sentimental figure. She is an emaciated beauty, her attenuated torso, bare breasts, tousle of thick hair, and squinting, downcast eyes surprisingly resembling some supermodels today. But the harsh realization of her life as a captive slave weighs down her sensuality with gravitas. She is, to quote one contemporaneous reviewer, “clever to the point of being painful.”[15]

The Crystal Palace’s afterlife in Sydenham Park as a showplace for plaster reproductions of ancient, Renaissance, and modern sculptures was the theme of the next bay. Although this was an important component of the exhibition and demonstrated the strong role of sculptural display during the nineteenth century, the reliance on photographs and books and only one painted plaster cast of the effigy of Eleanor of Aquitaine was a let-down, particularly after the previous installation of the three life-sized slaves. This could have been an opportunity for the curators to talk more about the production of plaster casts and their incredible popularity at the time, by showing at least one other work and perhaps a plaster mold to demonstrate the making of sculpture. It was refreshing, then, to move on to the next bay, “Sculpture and Antiquity,” with reproductions of ancient works, including casts of sections of the Parthenon frieze, and new classical interpretations, such as those by John Gibson, who arguably was the paradigm of classicism in the Victorian period.[16] Gibson’s statue Cupid Disguised as a Shepherd Boy, a recent acquisition for the YCBA, was the main work in this gallery (fig. 13). Commissioned in marble in 1834 by Robert Peel, the same year he was elected Prime Minister, this figure became the sculptor’s most reproduced work, with at least eight more commissions in marble produced afterward. Rather than merely emulate the classical past, however, Gibson and his followers embraced modernism by seeking out special crafts and new technologies in order to disseminate antiquity to the masses. The Parian Narcissus discussed above was one such example. Another seen in this bay was Gibson’s large painted plaster relief of Phaeton Driving the Chariot of the Sun, 1852, paired with a cameo designed by Tommaso Saulini after the relief, allowing one to wear sculpture as jewelry.

The next section of the exhibition was called “Craft and Art” and emphasized guild-minded New Sculpture from the 1870s on. According to the curators, these sculptures “were made with a purposeful ethos of craft, bringing a decorative idiom to bear on all facets of sculptural work,” and they exemplify “a shared commitment to a craft-orientated production, often collaborative in nature, but with an emphasis on the artisanal identity of the autonomous maker.”[17] Among these “autonomous makers” were names such as Alfred Gilbert that recent scholarship in Victorian sculpture has made more popular, but many of the works on display here were largely unknown sculptural objects. One of the more dynamic works was the life-sized statue of Dame Alice Owen, 1897, by George Frampton, made to commemorate the founder of the eponymous charitable school she established in the seventeenth century (fig. 14). Frampton used a combination of different marbles grouped with alabaster, bronze, paint, and gilding to create a hauntingly naturalistic representation of this woman. Another significant, and better known, piece on display was Edward Onslow Ford’s Singer, 1889 (fig. 15). Recently conserved, the sculpture has a restored green patina and gilding, giving it a refreshing appearance that more suitably places it within the Aesthetic Movement milieu. One of the more outstanding works in this gallery, however, installed near the end, was by William Reynolds-Stephens, a sculptor who clearly deserves a full reevaluation for his artistic achievements. The massive sculpture A Royal Game, 1906–11, shows Elizabeth I and Philip II playing an imaginary game of chess using ships, referencing the ultimate defeat of the Spanish Armada and the assertion of England over Spain in the late 1500s (figs. 16 and 17). Parallel in its installation to the effigy portrait of Elizabeth I in the “Sculpture and National History” section, the sculptures both reference the historical legacy of Elizabethan England in Victorian England, with two powerful female monarchs. But the two works also were made from electrotype technology, demonstrating aptly how sculpture at this time exemplified the joining of craft and technology with ideas of civic pride.

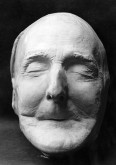

This section could have been an appropriate ending to the exhibition, but to the right was the last bay with the final component of the exhibition: “Sculpture and Commemoration.” The subject of this small area was the role of memorial sculptural programs, with an emphasis on the monument to the Duke of Wellington in St. Paul’s Cathedral. Although the Duke had died in 1852 and the commission for his monument by Alfred Stevens had begun in 1856, numerous delays stalled its completion until 1912. Designs and studies by Stevens accompanied painted plaster models of his Michelangelesque sculptures of Valour and Cowardice and Truth and Falsehood, and contemporaneous books and prints about the Duke’s funeral were presented in another area. The pièce-de-résistance in this bay, however, was the Duke’s death mask, made by George Gammon Adams three days after his death (fig. 18). The face reveals gray-tinted folds of flesh, a wrinkled brow, sunken cheeks, and a toothless mouth, and becomes a sad testament to the falling of a great hero to old age. Yet, somehow, the work also restores Wellington to life. It was an appropriate reminder as the final object that all of these sculptural works were the residual effects of long dead artists who designed, modeled, carved, cast, or inlaid them.

Sculpture Victorious was a successful exhibition in which little known, beautiful works in a variety of sizes and media were given an opportunity to be seen with fresh eyes and thus appropriately shine. For many of these objects, their strength lay not in who made them, but in how they were made, displayed, and perceived as tangible objects and symbolic images. The exhibition required of the viewer time, patience, and, most importantly, a keen eye. Only by looking intently and studying the works on display was the viewer able to take in and comprehend their texture, materiality, and craftsmanship. Indeed, the selection of objects in this exhibition reveals the keen curatorial eye that Droth, Edwards, and Hatt had in deciding what was essential to include and how to display it. This curatorial eye made the exhibition worth seeing.

If there was a major criticism to be made about the exhibition, it could be that some viewers may have left disappointed because their expectations were not met. Connoisseurs and lovers of Victorian culture may have anticipated this exhibition would highlight major artists of the period. Although famous sculptors such as Chantrey, Gibson, Gilbert, and Stevens were included, noticeably absent were sculptural works by Frederic Leighton or the Thornycrofts, which the YCBA owns.[18] The title of Sculpture Victorious, rather than simply Victorian Sculpture, also seems like a populist attempt to convince audiences of the show’s blockbuster appeal, disavowing the notion that it showed a bunch of dusty old tchotchkes from a long deceased great-grandmother’s house. If this was the intent of the curators, then certainly they succeeded, but this awkward title suggests an apology for the exhibition and potentially undermined the aesthetic power of the objects on display and the rich scholarship in the accompanying catalogue. The curators explain in the catalogue that the title emphasized the idea of victory and its symbolic association with Victoria—Christian Daniel Rauch’s Victory figurine was used to exemplify this—but this message did not come through in the exhibition because the figurine was too small and installed along the wall in the “Great Exhibitions” section. Had the work been installed in the opening section, it would have made much more sense, appearing alongside the representations of Victoria herself.

Sculpture exhibitions are notoriously challenging to mount. The expenses involved in international shipping, as well as insuring and installing large, heavy sculptures, frequently prohibits museums and galleries from showcasing major works one might want to include. Ceiling height restrictions, such as those in the second-floor galleries of the YCBA, also limit the ability to exhibit properly sculptures that might be more than six feet in height. One anticipates that the exhibition’s second venue at Tate Britain, where spacious galleries and fewer geographical restrictions to works in British museums and private collections, will enable the curators to display more monumental and major works that will properly elucidate the wider, all-encompassing history of sculpture from the Victorian period. The exhibition catalogue promises some of the significant pieces that one would want to see: the haunting Veiled Vestal by Raffaele Monti (1847); the dynamic Eagle Slayer (cast in iron in 1851) by John Bell; Frederic Leighton’s Athlete Wrestling a Python (1877); and Hamo Thornycroft’s lustrous bronze Teucer (1881). Of these, Thornycroft’s life-sized sculpture is a wonder to behold in person for its harmonizing of classicism with naturalism, its sensuality, and its balance of tension and release, all seen in the self-conscious micro-second the archer has just released his arrow (fig. 19).

The catalogue that accompanies the exhibition is impressive unto itself (fig. 20). With over 300 color illustrations, the photographic images emphasize the beauty and craftsmanship of the works in the exhibition. But this is not just a coffee table art book. The essays and 150 catalogue entries by a team of leading specialists will make this book a long-standing critical source for the study of nineteenth century sculpture in Britain. Sections of the book matched most of the themes of each bay in the exhibition, but the catalogue allows for a more thorough explanation of the curators’ intent regarding the nuances of Victorian sculpture production, display, and political history. The section on “Sculpture and Ceremonial” is probably the most interesting. Utilizing photographic documentation, this section focused on the numerous monuments to Victoria that were erected throughout the empire, from small cities in England to Australia, India, and South Africa. This section of the exhibition project best exemplified the grandiose idea of display through the numerous public memorials constructed during Victoria’s reign, but the materiality and size of these outdoor monumental sculptures obviously made it impossible for the curators to display these works. In the exhibition a stand-in was provided through a touchscreen monitor with digital images of archival photographs, but unfortunately the monitor was not working the day I visited. Another version of this same information is available online as an interactive world map and timeline with historical imagery and brief catalogue entries about the monuments (http://www.centerforbritishart.org/victoria-monuments/map).

Sculpture Victorious was an ambitious exhibition and catalogue that resulted in showcasing numerous rarely seen works, many of which were simply stunning in their aesthetics, designs, and executions. Emphasizing objects over makers, the curators forced the viewer to engage with these works as objects from a culture that took pride in sculpture as a means by which to express nationalism and to celebrate beauty, craft, and industry, over the course of the sixty-four years that was Victoria’s reign. Contrary to Janson’s dismissal of this period as “a dearth of sculptural talent,” the curators succeeded in demonstrating that there was in fact an incredible diversity and wide array of sculptural works in multiple media that celebrated the union between man and industry and permeated the lives of the Victorians, whether it was with large public monuments they saw on the streets or coins they may have held in their hands. To dismiss the exhibition and these works as merely “a reflection of a bygone era,” as one reviewer recently has done, is to have misunderstood the object-centric intent and curatorial eye of this show. Ultimately, this exhibition reminded the viewer that all sculptures are not just flat images in a book, but three-dimensional objects with unique traits and values that must be seen in person in order to be appreciated for how they were made and how they were displayed and utilized.

Roberto C. Ferrari, Ph.D.

Columbia University

rcf2123[at]columbia.edu

My thanks to Carolyn Conroy and Caterina Pierre for their feedback on a draft of this review, and, at the Yale Center for British Art, to Betsy Kim for her assistance with images and the catalogue, and to Martina Droth for her curatorial support.

[1] H. W. Janson, 19th-Century Sculpture (New York: Abrams, 1985), 162.

[2] Susan Beattie, The New Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983).

[3] Benedict Read, Victorian Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982).

[4] See, for instance: Martina Droth, “The Ethics of Making: Craft and English Sculptural Aesthetics c. 1851–1900,” Journal of Design History 17, no. 3 (2004), 221-35; Martina Droth and Penelope Curtis, Taking Shape: Finding Sculpture in the Decorative Arts, exh. cat. (Leeds: Henry Moore Institute; Los Angeles: Getty, 2009); Jason Edwards, Alfred Gilbert’s Aestheticism: Gilbert Amongst Whistler, Wilde, Leighton, Pater and Burne-Jones (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2006); Jason Edwards and Imogen Hart, eds., Rethinking the Interior, c.1867–1896: Aestheticism and Arts and Crafts (Surrey, England: Ashgate, 2010); Michael Hatt, “Thoughts and Things: Sculpture and the Victorian Nude,” in Exposed: The Victorian Nude, ed. Alison Smith, exh. cat. (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2002), 36-49; and Morna O’Neill and Michael Hatt, eds., The Edwardian Sense: Art, Design, and Performance in Britain, 1901–1910 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

[5] The elephant harkened back to the large taxidermy version seen at the 1851 Great Exhibition Indian pavilion, but it also related, albeit indirectly, to the large papier-mâché elephant concurrently displayed at the 1889 Exposition Universelle. This French elephant later was installed outside the Moulin Rouge.

[6] Having the introductory wall text on the left did create some confusion as to which direction the exhibition continued. Had the text been on the right wall, it would have led the viewer more logically in the direction in which the exhibition was intended to flow. My thanks to Caterina Pierre for this observation.

[7] For more on sculpture reduction machines and other related technologies of the early nineteenth century, see Michele Bogart, “In Art the Ends Just Don’t Always Justify Means,” Smithsonian 10 (June 1979), 104-11, and Meredith Shedd, “A Mania for Statuettes: Achille Collas and Other Pioneers in the Mechanical Reproduction of Sculpture,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts (July/August 1992), 36-48.

[8] Jonathan Marsden, ed., Victoria & Albert: Art & Love, exh. cat. (London: Royal Collection, 2010).

[9] It would have been useful in the exhibition to have an explanation of electroplate technology, in which sheets of metal were applied chemically onto metal or core objects. It is related to electrotyping, which chemically created metallic objects. For more information, see The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s video and summary from its exhibition (http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2011/electrotypes).

[10] “Sculpture and National History,” in Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901, eds. Martina Droth, Jason Edwards, and Michael Hatt, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 148.

[11] A recent exhibition and catalogue that explored the decorative arts in association with the world’s fairs was Jason T. Busch, et al., eds., Inventing the Modern World: Decorative Arts at the World’s Fairs, 1851–1939, exh. cat. (New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2012). Few of the essays address sculpture or the sculptural quality of works directly, but one essay by Martin P. Levy, “Manufacturers at the World’s Fairs: The Model of 1851,” 34-49, offers insights into manufacturers and art in the Victorian period and offers further information about these relationships addressed in Sculpture Victorious. My thanks to Janet Whitmore for reminding me of this source.

[12] “Exhibition of the Royal Academy,” Literary Gazette, June 2, 1838, 346.

[13] See, for instance, “Illustrated Tour in the Manufacturing Districts. Stoke-upon-Trent. The Works of Copeland and Garrett,” The Art-Union, November 1, 1846, 287-300. For more on the history and production of Parian ware, see Paul Atterbury, ed., The Parian Phenomenon: A Survey of Victorian Parian Porcelain Statuary and Busts (Shepton Beauchamp, Somerset, England: Richard Dennis, 1989). For more on Gibson’s involvement with Parian ware, see Roberto C. Ferrari, “Beyond Polychromy: John Gibson, the Roman School of Sculpture, and the Modern Classical Body” (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, CUNY Graduate Center, 2013), 203-9.

[14] It seemed unusual that the YCBA borrowed the Greek Slave from the Newark Museum of Art when the Yale University Art Gallery has a replica. Nevertheless, this became an opportunity to see each replica in proximity to one another and compare in person their similarities and differences.

[15] “The Royal Academy,” The Athenaeum, no. 1337 (June 11, 1853), 710.

[16] Gibson is most famous for the Tinted Venus, 1851–53, which premiered in London at the 1862 International Exhibition to mixed reviews. This sculpture appears in the catalogue, but disappointingly was not included in the exhibition, as it would have made for an excellent example of the revival of polychrome sculpture that developed over the century.

[17] “Craft and Art,” in Sculpture Victorious, 370.

[18] Leighton’s Self-Portrait, 1880, which shows the painter with plaster casts of the Parthenon frieze in the background, was displayed as a representation of a major Victorian artist’s interest in and reliance on sculpture for his oeuvre. However, the YCBA owns statuettes of The Sluggard, ca. 1895, by Leighton, and Thomas Thornycroft’s Queen Victoria on Horseback, 1853, and these could have been exhibited to provide evidence of works by these artists.