The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Félicie de Fauveau. L’amazone de la sculpture (1801–1886)

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

June 13, 2013–September 15, 2013

Previously at:

Historial de la Vendée, Les Lucs-sur-Boulogne, France

February 15–May 19, 2013

Catalogue:

Félicie de Fauveau. L’amazone de la sculpture.

Jacques de Caso and Sylvain Bellenger, with contributions by Hélène Becquet, Jean-Loup Champion, Anne Dion-Tenenbaum, Isabelle Dupire-Willette, Ophélie Ferlier, Barthélémy Jobert, Jack Johnson, Silvia Mascalchi, Erika Naginski, Florence Rionnet, and Claude Schopp.

Paris: Editions Gallimard in association with the Musée d’Orsay, 2013.

366 pp.; 154 ill. (color and b&w); bio-chronology; list of works; bibliography; index of names.

€45.00

ISBN: 978-2-35433-126-9 (Musée d’Orsay);

ISBN: 978-2-07-014008-4 (Gallimard) (softcover with jacket)

The Aim

After the exhibition on princess Marie d’Orléans (1813–1839) as a romantic artist at the Louvre in 2008, and the 2011 exposition Sculpture’Elles, Les sculpteurs femmes du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours at the Musée des Années ‘30 in Boulogne-Billancourt, the theme of the nineteenth-century female sculptor was on the cultural agenda in Paris once more in the summer of 2013.[1] The first retrospective exhibition dedicated to the French-Italian sculptor Félicie de Fauveau (1801–1886) was on display in the Musée d’Orsay—somewhat strange given her birthdate, that would generally attribute such an event to the Louvre (fig. 1). Even though it was a relatively small show for the museum (accommodated in rooms 8a, b, c and 9), no fewer than seventy sculptures, paintings, art objects and documents were on show (fig. 2). The focus this time around was not so much on the artist’s gender, but on her role and position in nineteenth-century sculpture.

The exhibition was organized jointly by a historical museum, the Historial de la Vendée (Christophe Vital), where it was to be seen first, and a fine arts museum, the Musée d’Orsay (Ophélie Ferlier), in cooperation with sculpture connoisseurs Jacques de Caso (professor emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley) and Sylvain Bellenger (Art Institute of Chicago). Manifestly, long and joint research by all partners preceded this project, providing it the potential to grant the artist her rightful place in art history.[2]

While it is generally assumed that Romanticism first broke through in sculpture at the 1831 Salon, de Fauveau had already presented a romantic work on her debut at the 1827 Salon—at the age of 26—with her high relief Christine, reine de Suède, refusant de faire grâce à son écuyer Monaldeschi [Christine of Sweden Refusing to Spare Monaldeschi, her Master of the Horse], a seventeenth-century historical subject (fig. 3). The archaic work, reminiscent of the troubadour painters, instantly received a gold medal second class, and the praise of important critics such as Alexandre Dumas and Théophile Gautier. Critics noted its originality, and according to Stendhal, Félicie de Fauveau was capable of replacing and/or succeeding Canova with the new path she was taking.[3]

In 1831 L’Artiste, a strong advocate of the ‘nouvelle école’ [new school] in sculpture, placed de Fauveau on a level with romantic sculptors such as Antonin Moine and Henri de Triqueti.[4] The latter has already received a proper exhibition, as have François Rude and Auguste Préault. In the mid-1830s Le Musée situated the innovative and inspiring character of de Fauveau’s work at the intersection between iconography and style; La Mode called her “the hope of the young art of sculpture”.[5] In 1842 Armande Loyer de Maromme, a friend of Félicie’s mother, wrote three long articles in L’Artiste on ‘Mademoiselle Félicie de Fauveau, sculpteur’ [Miss Félicie de Fauveau, sculptor] in which she called de Fauveau “original”. A copy of one such article could be seen in a showcase in the first room (figs. 4, 20). In the same year, the Bulletin des Salons was in no doubt about the innovation that Félicie was bringing: “She seems to have opened up a new direction for sculpture, and to date she is the only one taking it.”[6] One year after her death, Baron de Coubertin, too, described her work as new and inventive.[7]

In line with such contemporary critics, the exhibition presents de Fauveau as “original”, as a pioneer and innovator, on the one hand because she was “the first” woman sculptor (actually one of the first) to turn professional, living off her art, irrespective of her noble birth; and on the other hand because of the artistic characteristics of her work, described as a “new direction”.[8] Given the focus on innovation in modernist art history, this thesis may contribute to a more secure position for Félicie de Fauveau in the art historical canon. A possible risk of being typified as “original”, “unique” or “exceptional”, however, can have exactly the opposite effect: marginalization as a result of deviating from the norm. Many (women) artists suffered that lot, especially in twentieth-century art history. De Fauveau, together with Marcello and Camille Claudel, was one of the few nineteenth-century sculptresses not to be scrapped from the canon altogether in the course of the past century.

In the press announcement of the catalogue, de Fauveau is positioned as a central and crucial figure in Romantic sculpture: “Ineluctable figure of Romantic sculpture, next to Antoine-Louis Barye, Antonin Moine or Auguste Préault.”[9] It is not clear, though, how sentences like these in the leaflet can, or will, be interpreted: “Her work does not comply with modernist criteria as we see them in the twenty-first century: in spite of her affinity with Romanticism and the Neo-Gothic, she travels her personal road in the margins of fashions and styles. Even the way she dresses is anachronistic (. . .).”[10] It is surely not helpful for her position in the canon to situate her in the margins of French Romanticism, instead of at its center or as its pioneer—a position that many of her contemporaries attributed to her.

On the occasion of the 1831 Paris Salon, in which she did not exhibit as she was then politically active, a critic claimed in L’Artiste that Henri de Triqueti was following in de Fauveau’s footsteps: “Unfortunately Miss De Fauveau, who fulfilled this mission with such merit in previous exhibitions, has not exhibited anything this year. Mr de Triqueti, who is following in her footsteps and works in a very similar style, took her place.”[11] The same author also praised her as a pioneer as she was the first sculptor to revive the lost wax method of bronze casting in collaboration with Jean-Honoré Gonon, who rediscovered this old process that had fallen into disuse in France.[12] In this, too, De Triqueti, and many after him, followed de Fauveau. Although she might have been one of the most archetypical Romantic sculptors, she was largely ignored from the late nineteenth century onwards, in part because of her emigration to Italy.

Unfortunately, too, for de Fauveau’s inclusion or consolidation into art history, all of the museum exhibition’s communication was offered only in French—quite unusual for the Musée d’Orsay, and curious as two main organizers (albeit of French origin) are active in the US (fig. 5). This, plus the fact that the exhibition did not travel outside France, are, however, just about the only negative points of this event, and they are undoubtedly not due to a lack of ambition, but rather to a lack of funding. The success of this exhibition is due not only to the popular Paris venue, but also to the high quality and rarity of the exhibits, the attractive scenography, the coherent set-up of the installation, and the appealing story of the artist.

The Exhibits

Félicie de Fauveau was celebrated in her time, but fell into oblivion shortly after her death, as was the case for many artists. As many of her artworks ended up in private collections, only a few were well-known, mostly through old reproductions. The greatest merit of this exhibition lies in tracing and disclosing a large number of artworks by Félicie de Fauveau and of documents relating to her. They were rediscovered in public and private collections in France, Italy, Germany, Scotland, Austria and Russia, among others. In the catalogue, a great-great-nephew of Félicie de Fauveau, who never married and never had children, is specifically thanked for making available “documents, objects and artworks”. Over a thousand pages of letters from and to de Fauveau or her entourage—a veritable treasure trove—were recovered, examined and transcribed for the first time, so the catalogue tells us.[13] They featured fragmentarily in the exhibition and catalogue, and probably deserve another publication in full.

Even some of the objects that couldn’t be traced were present, via a drawing, print or photograph, such as Le miroir de la vanité [The Mirror of Vanity], shown as a print in Le Magasin pittoresque of 1839, in a showcase in the third room (fig. 6). In this room, the visitor could also use a touchscreen to browse the album Ouvrages, from a Scottish private collection, with drawings and pictures of many of de Fauveau’s projects and realizations (among them the same mirror), an instrument of inestimable value for further investigation (fig. 7).[14]

Nothing but praise should be given to the in-depth research underlying this exhibition as well as the assembling of the artist’s many scattered works. It is a pity, though, that some of the best pieces are missing, such as the large marble Monument à Dante [Monument to Dante], depicted in Luc-Benoist’s famous essay on La sculpture romantique from 1928; this is all the more disappointing as this impressive work for the wealthy banker and collector James-Alexandre de Pourtalès-Gorgier is today in a private collection in Paris. In order to compensate for its absence, the curators (expressing their regret in the catalogue that some owners refused to lend their works) presented a later and smaller bronze variation on the lower part of the Monument à Dante, depicting a semi-nude Paolo and Francesca in hell, from another private collection (fig. 8). Similarly, Félicie de Fauveau’s lost bronze group, Charles VIII à cheval entrant en Italie [Charles VIII on horseback entering Italy], was ‘present’ via its pendant, the bronze Saint Georges terrassant le dragon [Saint George subduing the dragon] (1832, Musée du Louvre, Paris) by Paul Delaroche (fig. 9; middle object). Both pieces were commissioned by Count Amédée de Pastoret for one of the carrés [squares] of the Champs-Elysées.

The exhibition also realized a few unique juxtapositions. In the last room, for example, the marble holy-water font with a protecting angel, sculpted for the Countess de La Rochejaquelein, is shown next to an anonymous painting of Félicie de Fauveau working on the same object (ca. 1840) (fig. 10).[15] In the background of the portrait, de Fauveau’s Monument for Dante can also be seen. Another example is the polychrome wooden pedestal by Félicie and Hippolyte de Fauveau that, in the exhibition, supports François-Joseph Bosio’s bronze sculpture of Henri IV as a child (1826), just as Anatole Demidoff ordered it around 1845 (fig. 11).[16]

Around the same time the latter also had Félicie and Hippolyte de Fauveau decorate Paul Delaroche’s famous painting Lady Jane Grey, purchased at the 1834 Paris Salon for his villa San Donato near Florence, with a sumptuous gilded wooden frame. In the exhibition, a life-size grisaille reproduction of the canvas provided a convincing alternative to present the remaining frame fragments (fig. 11). The catalogue also shows a decorative golden frame designed by Félicie de Fauveau for the Portrait of Dante (1841–42, private collection) by her friend Antonio Marini, the Tuscan painter who shared her fascination for Dante.[17]

The Scenography

The visitor who understands French is offered plenty of information concerning the artist, her life, work and historical context, both in general and concerning specific pieces, in clear and elegantly formatted text panels, summary texts on several labels, and in a leaflet available at the entrance (containing a plan, basic information and six illustrations) (figs. 5, 8, 14).

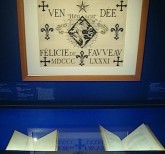

The pieces themselves are attractively presented. One color was chosen for all walls, plinths and showcases, visually linking the four rooms seamlessly: royal blue, magnificently combined with gold (inside the vertical showcases and in lettering, and recurring in the paintings’ frames) (figs. 2, 4, 5, 9, 25, 28).[18] This is no arbitrary choice, but reminiscent of the late Gothic Sainte-Chapelle in the heart of Paris, that Félicie de Fauveau knew and admired. The Gothic framing of her marble Bénitier de Saint-Louis [Holy-water font of Saint Louis] from the Palazzo Pitti in Florence reflects the exterior of the Parisian chapel, and the head of St. Louis’s statue in Sainte-Chapelle served as a model for her eponymous saint. This building was damaged during the French Revolution, but restored in the mid-nineteenth century by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, who visited de Fauveau in Florence in 1837 (followed by Honoré de Balzac a few months later). Opting for the deep, rich blue combined with warm and directional lighting makes the rooms seem somewhat dark, but it makes for a certain intimacy and sanctity, and beautifully showcases the white marble pieces with neo-Gothic and neo-Renaissance inspired forms.

The objects are nicely spread out, with a variety of paintings, reliefs, prints and drawings on the walls, sculptures positioned at different heights, usually without protective glass, while documents are presented in horizontal showcases (figs. 4, 18, 20, 23, 25). In the second room, the marble portraits are carefully placed to engage with each other in dialogue and to bring out their similarities, particularly de Fauveau’s formula for the depiction of aristocratic models embedded in an architectural framework with inscriptions in a decorative niche or mandorla, and adorned with crests and symbols linked to the monarchy of the Ancien Regime (fig. 12). Two exceptions are the more conventional, full-round, slightly baroque and meticulously chiseled marble busts of the flamboyant François Dudon and viscount Brétignières de Courteilles, presented together (fig. 13).

The Set-up and the Story

The exhibition consists of four, consecutive, rather small rooms, in which the visitor follows a clear route, yet unfortunately has to pass briefly via the common, well-lit hallway to enter the final room, which temporarily halts (or possibly finishes) his visit (figs. 2, 5). The four rooms each have one general theme, although these are only mentioned in the leaflet, except for the third room, where the general theme is identical to the caption. The other three rooms contain two to three text panels covering sub-themes. Next to all text panels, relevant works and documents are coherently and consistently grouped (figs. 5, 8, 14).

In room one, the largest of the four rooms, the general theme is ‘Le ciseau et l’épée’ [The chisel and the sword]; it contains three sub-themes/text panels summarizing Félicie de Fauveau’s life story more or less chronologically: ‘Les débuts de Mlle de Fauveau’ [Mademoiselle de Fauveau's Early Career] (fig. 14), ‘L’épopée Vendéenne’ [The Epic Events of the Vendée] (fig. 8), and ‘Florence, refuge et foyer’ [Florence, Refuge and Home] (fig. 5). Her life story runs roughly parallel with the political history of France in the first half of the nineteenth century: successfully starting her career in Paris under the Restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, she then took part in the uprising against the July Monarchy of Louis-Philippe in the Vendée, and ended up in exile in Florence, where she was visited by, and mainly worked for, (disaffected) royalist aristocrats.

Félicie de Fauveau is presented as an intransigent conservative and an uncompromising legitimist—adherent of a hereditary God-given monarchy (of the Bourbons), but at the same time as an endearing, independent single woman and a somewhat masculine feminist (maybe a lesbian too).[19] This room introduces the visitor to de Fauveau through the eyes of her contemporaries beginning with a series of drawings by Camille Chenou, portraying a young girl with long hair, wearing skirts (fig. 14). From 1829-1830 on, Paul Delaroche, Ary Scheffer, and Félicité Beaudin all portray de Fauveau with her hair cut short (‘au carré’), wearing a long robe or skirt in velour, like the amazons, complemented with a man’s waistcoat, a studio apron and a red beret (fig. 15).

Several contemporaries who visited de Fauveau in Florence, such as the sculptor Jean-Marie Bonnassieux or Marie Dumas, described her outfit in similar terms and commented on “this habit of hers to dress as a man”, on her being simultaneously “homme et femme” [man and woman], or called her “mademoiselle l’abbé”.[20] For the Fratelli Alinari photographers in Florence, the sixty-year old Félicie de Fauveau posed in similar attire, with a hammer in her hand, next to one of her sculptures, explicitly manifesting herself as a sculptor (fig. 16). She also depicted herself resolutely in such costume in her marble self-portrait (1846) with her beloved dog, at the entrance of the exhibit (fig. 17).

In the catalogue, Jean-Loup Champion makes an interesting comparison between this self-portrait and Marie d’Orléans’s (1813–1839) then widely known Jeanne d’Arc (1834), an androgynous figure with similar short hair (‘au carré’) and downcast eyes, showing a similar pose, modest and introspective.[21] Champion remarks that it is surprising that de Fauveau did not depict Jeanne d’Arc, even though she must have felt an affinity with her, as a woman breaking conventions of her time, influencing the course of history and saving their king; it may even have inspired her for sporting men’s clothing and short hair. D’Orléans’ popular Jeanne d’Arc may indeed have been one of the reasons why de Fauveau did not depict her.[22]

Soon after Félicie’s birth in Livorno, Italy, her family—of French financiers ennobled in the eighteenth century—left for Paris. There she learned how to paint before discovering sculpture in Besançon (where they moved) while talking to a craftsman producing religious statues, but little is known about her training. Some deduce from this a lack of schooling and skill. De Fauveau herself maintained the myth that she was self-taught, learning her art by studying books about history, heraldry and art, and making copies from medieval, especially Gothic, and early Renaissance art. She kept those copies in albums, two of which were on display at the exhibition (fig. 18). After her father’s death in 1826, her mother returned to Paris with their four children, where Félicie embarked on an artistic career to help support the household. They lived in the Nouvelle Athènes quarter in the ninth arrondissement, at that time the place to be for the elite of the Parisian Romantic movement. Félicie’s mother hosted an influential salon there; and de Fauveau established a studio next to that of Ary Scheffer, six years her senior and initially a friend of hers (fig. 19). She also frequented Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Antoine-Jean Gros; she would later sculpt a memorial to Gros and his wife (fig. 28).

Following her first success at the 1827 Paris Salon (where Delacroix presented his Death of Sardanapulos), de Fauveau's career took off, and by 1830 she was a promising Parisian artist with an enviable reputation. She was commissioned by King Charles X, to whom she was related, to sculpt two doors for a gallery in the Louvre; she designed a tabernacle for the Metz cathedral (not executed); and for the Comte de Pourtalès, she produced the Monument to Dante. She also enjoyed the protection of the influential Duc de Duras, whose daughter Félicie (later countess de La Rochejaquelein) became her lifelong friend.

Together with her, Félicie de Fauveau compromised herself in an uprising against the new king, Louis-Philippe I, Duc d'Orléans, after Charles X was forced to abdicate in 1830. Being passionately loyal to the elder branch of the Bourbon dynasty, de Fauveau rejoined the Comtesse de La Rochejaquelein at her chateau in the Vendée, which became a stronghold of the legitimist conspiracy. Combining medieval chivalry and religious faith, de Fauveau produced emblems, symbolic works, bracelets and decorative military elements for her comrades in arms, such as the banner for La Rochejacquelein’s division (figs. 4, 8). Most feature the figure of Saint Michael, symbol of divine justice, the victory of Good over Evil, and patron saint of the French Catholic church, of medieval France, and of the legitimate heir to the throne, Henri d'Artois (later Comte de Chambord). Once exposed, de Fauveau became the “héroine de la Vendée” but was imprisoned for three months; on the prison wall she designed a monument to her deceased companion Charles de Bonnechose, which was never executed, but can be found in the exhibit as a lithograph (as it was distributed in legitimist circles at the time), as is Félicie de Fauveau’s project for her own funerary tomb (realized in Florence). This mentions the activities in the Vendée that affected her forever: ‘Vendée – Labeur Honneur Douleur’ [Labour Honor Grief] (fig. 20). In a nearby case was a copy of de Fauveau’s Mémoires, transcribed by Constance Bautte de Fauveau in 1894, which describe these two poignant and decisive years in her life.

After the failed uprising, she broke off her friendship with Delaroche and Scheffer, whom she accused of treason. Notably, Scheffer became the private teacher of Louis-Philippe’s children, including the princess Marie-Louise d’Orléans, who was a sculptor too. Regardless of the princess’s political background, however, Félicie de Fauveau did respect her as an artist, and even publicly defended her against accusations concerning the authorship of her work.[23]

On her release from prison in June 1832, Félicie de Fauveau briefly took up arms again in support of the Duchesse de Berry, mother of the legitimist candidate (fig. 21). Found guilty in absentia, Félicie de Fauveau had no alternative in 1833 but to leave France and go into compulsory exile, settling in Florence for the rest of her life, in spite of the general amnesty of 1837.[24] She soon reconstructed her studio, which had been hurriedly dismantled in Paris. Nevertheless, she still sent work to the Paris Salon, but only returned to that city for six months in 1844–45.

In Florence, her work became greatly influenced by the golden age of Italian art. Room one shows her album Italiens (private collection, Edinburgh), containing mainly drawings and photographs of paintings from Tuscany, with a preference for Giotto and Domenico Ghirlandaio (fig. 18). Full-round sculpture is surprisingly under-represented, probably because de Fauveau considered sculpture an integral part of architecture, after the model of French cathedrals and Italian duomi.

For the architectural design elements of her own projects, she worked with her brother Hippolyte de Fauveau. He became her assistant, praticien and studio manager (until their break-up in 1872), and together they also bought and sold paintings. At the height of her activity around 1840, Félicie de Fauveau employed four praticiens to assist her in cutting the marble, and temporarily hired a supplementary studio. On exhibit were two anonymous portraits (one bought by the Historial de la Vendée in 2004) showing Félicie de Fauveau in her second and last studio in Florence, respectively at the Piazza del Carmine, where the family moved in 1843, and in the Via del Serragli, where they took possession, in 1851, of part of the ancient convent of Santa Elisabetta delle Convertite (fig. 5). De Fauveau’s fame acquired a European dimension as her studio became an essential stop for cultured tourists, curious art lovers and aristocratic clients. Here she first showed her finished Monument à Dante to the public in August 1836. Her studio was adorned with fabrics and wall hangings for the visits of illustrious persons like the Tsar of Russia and his daughter Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna, the Lindsay-Crawford families, or the Comte de Chambord.

Henri d'Artois, the Duc de Bordeaux, who became the Comte de Chambord under the July Monarchy, was the Legitimist pretender, whom the Vendéens unsuccessfully tried to place on the throne, as Henry V. He is a central figure in Room two, devoted to the Legitimist circles. There are two text panels: ‘Le culte d’Henri V’ [The cult of Henri V] and ‘Un légitimisme intransigeant’ [Intransigent Legitimism]. During his visit to Rome in 1839, the Comte de Chambord received Félicie de Fauveau, and their meeting was a true revelation for her (as appears from her letters to the countess de La Rochejaquelein), further reinforcing her belief in the monarchy by divine right and the royal succession based on the principle of birthright. After their meeting, he consented to pose for a portrait bust; de Fauveau made two models, and in the following years made about fifteen versions for Legitimist circles (fig. 12). De Fauveau did not so much depict the Comte de Chambord as an individual, but as the worthy heir of a dynasty. Even though his archaic portraits do not contain hands, his ‘royal’ hand was molded in plaster by Hippolyte de Fauveau, utilizing the common practice of moulage sur nature [molding from nature]. On his visit to Florence two months later, the Comte de Chambord ordered a portrait medallion (Musée du Louvre) from Félicie de Fauveau, which was shown in a showcase next to a letter he gave to her, written by King Henri IV in 1607 (fig. 22). She also realized the portrait of the count’s mother, the duchess de Berry (fig. 23).

De Fauveau’s portraits typically possess the characteristic features of their sitter, usually somewhat flattered, and mainly highlight the status and noble birth of her models—mainly legitimist aristocrats and royalist foreigners who flocked to her studio, as well as family and friends. She preferred high relief (fitted into some neo-Gothic architectural frame designed by Hippolyte) to sculpture in the round, in order to add coats of arms, royal symbols highlighted with polychrome details (mainly gold), and Gothic-style inscriptions in medieval French and Latin. Such Latin inscription can also be found on the surprisingly modern Pied droit de la danseuse Fanny Elssler [Right foot of dancer Fanny Elssler], presented in the first room. (figs. 5, 24) For this portrait and tribute in the shape of a body fragment, Félicie de Fauveau also used the process of moulage sur nature.

The third room, entirely devoted to the decorative arts (‘La renaissance des arts décoratifs’), revealed and positioned de Fauveau as an all-round artist, not restricting herself to the fine arts, but transcending the boundaries between disciplines. Like the Renaissance sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini, whom she admired and was compared to as ‘Benvenuto Cellini in skirts’, or like her contemporary Henri de Triqueti, she worked with many different materials and formats, realizing different types of objects with different functions.[25] De Fauveau designed and realized jewelry (bracelets, brooches, necklaces, and earrings), watches, rosaries, crowns, paper knives, daggers, mirror frames, picture frames, chimney pieces, ceiling decorations, and stained-glass windows (fig. 11, 25, 26). The Franco-Belgian lithographer and photographer Marcellin Jobard, then director of the Musée de l’Industrie of Brussels, wrote in 1842 that: “There isn’t anyone of importance visiting Florence who doesn’t take pride in getting a walking stick handle, a dagger handle or some bronze vase from Miss Fauveau, worthy follower of Cellini.”[26]

In the same year, Armande Loyer De Maromme pointed out Félicie de Fauveau’s versatility as an artist with Cellini as an inspiration: “Miss de Fauveau was destined to be a sculptor, not like Canova or de Bosio, but in the tradition set by Benvenuto Cellini and Michelangelo; in the sense and spirit of Renaissance; at the same time sculptor, architect and colorist, embracing art both as monument, decoration and industry.”[27] Many of her contemporaries, however, did make strict distinctions between the different disciplines; her wooden, richly decorated, yet morally charged Miroir de la Vanité [Mirror of Vanity], though admired by Théophile Gautier, was refused for the Paris Salon by the fine arts jury for being an industrial object, and by the industry jury for being an art object (fig. 6).[28]

Yet Félicie de Fauveau never developed a lucrative serial or industrial production; her refined art objects were almost always unique and made in close collaboration with only the best collaborators-artisans, such as the renowned foundry master, Honoré Gonon, who produced the lost-wax casting of her amazing Lampe de saint Michel [Lamp of Saint Michael], recently acquired by the Louvre and providing the publicity image of the exhibition (figs. 1, 25, 27). This polychrome and abundantly detailed object is also ‘telling’ in the sense that inscriptions add symbolic meaning. It is indicated on the lamp that it has been realized on the patron’s day of Saint Michael—birthday of the Comte de Chambord—of 1830, the first day of the reign of ‘Henri V’ as expected by his followers, and it bears the name of the psalm that inspired the lamp: “Orate et vigilate” [pray and keep watch].

The last room treats the religious and—once more—royalist piety of Félicie de Fauveau (“Piété religieuse, piété royaliste”) by showing the recurring religious objects, funerary monuments and decorative items in her work for princes and aristocratic patrons. In the second exhibition room the visitor saw de Fauveau’s album with photos of clergy, aristocrats, benefactors and intimates. In the fourth room, the importance of aristocratic patrons was again highlighted, this time in the form of projects for Russian royalty. Following commissions from Maria Nikolaevna, the Grand Duchess of Russia, de Fauveau met her patron’s father, Tsar Nicolas I, whose autocratic rule de Fauveau much admired. On a visit to her studio in 1846, the Tsar commissioned a marble Fountain with Nymph and Dolphin—the central piece of the last room—for the terrace of the Cottage Palace in Peterhof, a rare example of a female nude in de Fauveau's work (fig. 28).

In the back of this room was an extraordinary marble high-relief of Saint-Michel terrassant le dragon [Saint Michael subduing the dragon], partially gilded and combined with a sword and spear in real metal, representing the archangel chasing the evil before the gate of a castle, symbol of the gates of paradise (fig. 29). It was bought, without de Fauveau’s knowledge, for the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, Adolphe Thiers, by the sculptor Carlo Marochetti, which she considered treason.

In another part of the room, a Gothic church was successfully evoked as a setting for the religious works that Félicie de Fauveau—deeply religious—produced for Catholics, Anglicans, and the Orthodox, such as a poignant wooden Christ on the Cross for the chapel of the La Rochejaqueleins (fig. 28).[29] The preparatory drawings for the three angels at the upper ends of the cross could be noticed by the attentive visitor on the touchscreen presentation in room three. In the 1850s and 1860s Félicie and Hippolyte de Fauveau realized numerous funerary monuments for churches in Italy, France and the UK (there mainly for the Lindsay family). Several of de Fauveau’s saints and holy-water fonts were primarily intended for private devotion, however, and were elevated to the level of precious objects.

The Catalogue

The beautiful book accompanying the exhibition is a true scholarly work full of new information—in text as well as images. The book consists of three parts (yet not named as such). First, nine essays treat different aspects of the sculptor and her historical context. Secondly, the catalogue contains nine illustrated articles discussing specific groups of works, such as the portraits, jewelry, architectural realizations, or death in the oeuvre of Félicie de Fauveau. Thirdly, the appendices, some 65 pages, conveniently in paper of another color and texture, consist of a bio-chronology, a list of works, a bibliography, an index of names and the photo credits.

The fairly extensive table of contents somewhat hampers clarity, however, and its logic is not always obvious; even if the division between essays and catalogue seems lucid, it appears slightly artificial. One might ask whether some texts could not have been merged into one longer, subdivided text. The articles on de Fauveau as a Parisian sculptor and on her correspondence might have been better placed in the essay part. The involvement of thirteen authors is undoubtedly a factor in this.

The chronological list of works is an understatement for an undeniably concise, yet highly valuable catalogue raisonné, compiled by Ophélie Ferlier and Marie-Elisabeth Loiseau. Every object is listed with its basic data (dimensions, material, place, date); a summary history of the object (patron, former collections); contemporary and later exhibitions showing the work; references in literature and in correspondence; and, when possible, a reference to an illustration elsewhere in the book. The list does certainly not contain all artworks designed and made by Félicie de Fauveau (those are estimated around four hundred), but all those about which there is certainty and documentation, both localized and non-localized.[30] Each object also has a designation of whether it was exhibited in the Historial de la Vendée, in the Musée d’Orsay, or in both places. In total, 92 objects by Félicie de Fauveau are listed, some realized in collaboration with her brother Hippolyte. Also seven objects owned by her are listed, as well as eighteen letters, manuscripts and printed pieces (probably the reason for ranging the text on the correspondence in the catalogue), and 35 comparative works, such as photographic and painted portraits of Félicie de Fauveau.

Being a royalist, a Catholic, a single woman and a feminist simultaneously—not an obvious combination—Félicie de Fauveau was definitely a fascinating sculptor who committed her life and art to defending a political utopia. Hopefully this exhibition and catalogue, based on serious research and precise presentation, will be able, in spite of their monolingual French output, to contribute to a qualified consolidation of Félicie de Fauveau in art history.

Marjan Sterckx

Ghent University, Hasselt University, and MAD-Faculty

marjan.sterckx[at]ugent.be, marjan.sterckx[at]uhasselt.be, marjan.sterckx[at]pxl.be

The author only saw the exhibition in the Musée d’Orsay and not in the Historial de la Vendée. She wishes to thank Ophélie Ferlier and Annabelle Matthias of the Musée d’Orsay for their help and for allowing her to make installation views of the exhibition, as well as Janet Whitmore for her useful editing work.

[1] It is surprising that there is no reference in the de Fauveau catalogue to this exhibition and catalogue under the direction of Anne Rivière and Frédéric Chappey, whereas Félicie de Fauveau gets a prominent place.

[2] The Historial de la Vendée already bought several artworks from, or representing, Félicie de Fauveau during the last decade, as signaled by the French newsletter La Tribune de l’art.

[3] Jacques De Caso, "Félicie de Fauveau. Oubli. Naissance" in: Félicie de Fauveau. L'amazone de la sculpture (Paris: Musée d'Orsay, Editions Gallimard, 2013), 13–21; 16.

[4] Luc-Benoist, La sculpture Romantique (Paris, 1928), 89.

[5] Le Musée, 1834, 74; La Mode, 1837, 218.

[6] Bulletin des Salons, 1842, 354: "[elle] semble avoir ouvert à la sculpture une voie nouvelle, dans laquelle seule elle a su marcher jusqu’à ce jour." Translations into English by Raf Erzeel.

[7] Baron De Coubertin, "Mademoiselle de Fauveau," Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 35 (1887), 520.

[8] In the exhibit she is presented as the first professional sculptress, yet there were others preceding her, among them, in France, Marie-Anne Collot (1748–1821) and Julie Charpentier (1770–1845), for whom it was, however, harder to make a living from their sculpting; it might be better to speak of “one of the first professional sculptresses”.

[9] “Figure incontournable de la sculpture romantique à côté d’Antoine-Louis Barye, Antonin Moine ou Auguste Préault.”

[10] Exhibition leaflet, distributed at the entrance: "Son oeuvre ne répond pas aux critères de la modernité donnés par notre sensibilité du XXIe siècle: malgré ses affinités avec le romantisme et le néo-gothique, elle suit une voie personnelle en marge des modes et courants stylistiques. Son costume même est anachronique (. . .)".

[11] L’Artiste, vol. II, 1831, 14: "Malheureusement, mademoiselle de Fauveau, qui avait rempli cette mission avec tant de mérite aux expositions précédentes, n’a rien exposé cette année. M. de Triqueti, qui marche sur ses traces et travaille dans un goût tout-à-fait analogue, paraît à sa place."

[12] L’Artiste, vol. II, 1831, 14; Anne Dion-Tenenbaum, "Félicie de Fauveau et les arts décoratifs" in Félicie de Fauveau. L'amazone de la sculpture, 108–127; 111–112; Marjan Sterckx, Sisyphus' dochters. Beeldhouwsters en hun werk in de publieke ruimte (Parijs, Londen & Brussel, ca. 1770–1953), 2 vols (Brussels: KVAB Press, 2012), 355.

[13] De Caso, 2013, 15.

[14] A photo of the mirror in the album Ouvrages is depicted in the catalogue, cat. no. 16, 143.

[15] The object bears a verse from psalm 16: “Sub umbra alarum tuarum protege me” [“Hide me in the shadow of your wings”]. In La Mode (of legitimist and not of orléanist signature), which clearly came out in favor of Félicie de Fauveau and against Marie d’Orléans, daughter of Louis-Philippe, this holy-water font was praised in a separate article: “Un bénitier, par Mademoiselle de Fauveau,” in La Mode: Revue des modes, 1838.

[16] The exhibit shows an exact copy of Bosio’s work from Versailles, whereas the original is at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, just as the pedestal—an understandable choice.

[17] Silvia Mascalchi, "Félicie de Fauveau à Florence" in Sylvain Bellenger, Jacques de Caso and Ophélie Ferlier, Félicie de Fauveau. L'amazone de la sculpture, 72. Like her contemporaries she read Dante, Shakespeare, Walter Scott, etc. The Wallace Collection in London preserves the original frame designed by Félicie de Fauveau around Ary Scheffer’s large painting Paolo et Francesca, which unfortunately did not make it to Paris.

[18] In the Historial de la Vendée, purple was chosen for the color. See Didier Rykner’s review in La Tribune de l’art: http://www.latribunedelart.com/felicie-de-fauveau-1801-1886-l-amazone-de-la-sculpture.

[19] Guy Cogeval (Musée d’Orsay) uses the word lesbienne [lesbian] in his introduction to the catalogue, whereas Christophe Vital mentions on the adjacent page that Félicie de Fauveau was sans doute [without doubt] in love with the young [male] page who died in the Vendée [Charles de Bonnechose, for whom Félicie designed a monument on her prison wall]. Michelle Facos also explicitly suggests that Félicie de Fauveau might have been a lesbian in her Introduction to Nineteenth-Century Art (New York and London: Routledge, 2011), 103. Usually her relationship to the Countess de la Rochejaquelein is then referred to.

[20] "[C]ette manière qu’elle a de s’habiller en homme."

[21] Jean-Loup Champion, "Être Soi. Les Représentations de Félicie de Fauveau" in Félicie de Fauveau. L'amazone de la sculpture, 168. An illustration of Jeanne d’Arc by Marie d’Orléans can be found on http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn_08/articles/ster_27.html.

[22] Champion, 2013, 168.

[23] Isabella Blagden, "Félicie de Fauveau," The English Woman’s Journal, 2:7 (September 1, 1858), 86; De Chennevières, 1884; Sterckx, 2012, 372.

[24] Even though various sources state that Félicie de Fauveau first went into exile in Belgium before going to Italy, this little-known stay is not mentioned in the exhibition and catalogue. See Marjan Sterckx, " ‘Dans la Sculpture, moins de jupons que dans la Peinture’: Parcours de femmes sculpteurs liées à la Belgique (ca. 1550–1950)," Art&Fact 24, Femmes et créations, Alexia Creusen, ed., 2005, 56–74; 64.

[25] See De Caso, 2013, 16: “Benvenuto Cellini en jupons”.

[26] Jean-Baptiste-Ambroise-Marcellin Jobard, Rapport sur l’Exposition de 1839 (Brussels, 1842), 33: "Il ne passe pas un personnage de distinction à Florence, qui ne tienne à honneur de rapporter un pommeau de canne, un manche de poignard ou quelque vase en bronze de Mlle Fauveau, digne émule de Cellini."; Anne Dion-Tenenbaum, "Félicie de Fauveau et Les Arts Décoratifs" in Félicie de Fauveau. L'amazone de la sculpture, 108–27; 118.

[27] Armande Loyer De Maromme, "Mademoiselle Félicie de Fauveau, sculpteur," L’Artiste 3:1 (1842), 5–10; 7: "Mlle de Fauveau devait être sculpteur, non pas à la manière de Canova ou de Bosio, mais dans la ligne tracée par Benvenuto Cellini et Michel-Ange ; dans le sens et l’esprit de la Renaissance ; à la fois statuaire, architecte et coloriste, embrassant l’art comme monument, comme décoration et comme industrie."

[28] Dion-Tenenbaum, 2013, 109, 125.

[29] At the first World Fair of Paris in 1855 Félicie de Fauveau also exhibited a silver Crucifix (location unknown), and two other works, thanks to Philippe de Chennevières.

[30] No point of view is taken on a few works of art possibly attributable to de Fauveau (e.g. in the Paris Sainte-Elisabeth church, or at the Hendon cemetery for the Lindsay family). See Sterckx, 2012, vol. 2, 93, 194.