The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

The Forgotten Pendant of Christian August Lorentzen’s Model School at the Academy

Christian August Lorentzen (1746–1828) executed Model School at the [Royal Danish] Academy (fig. 1) prior to the institution’s pedagogical expansion of the 1820s, which introduced supplementary instruction in painting from life under natural light. The work’s subject matter, a Professor blandly lecturing to his pupils, may have inspired similar scenes of artistic training by Wilhelm Bendz (1804–32), Christen Købke (1810–48), and Martinus Rørbye (1803–48), among others; and its content sounded the death knell of classical pedagogy’s stranglehold on the Danish academic curriculum.[1] Model School at the Academy, now in the collection of the Museum of National History at Frederiksborg Castle, was likely displayed in Lorentzen’s apartment, the site of his private collection and a gathering place for local artists and visitors to Copenhagen.[2] Despite the picture’s significance and visibility, it is only partially understood. Seldom mentioned in relation to the painting is its missing pendant (sidestykke) The Monk Barthold Schwartz, Inventor of Gun Powder.[3] Documentation of the companion piece exists from its public debut in the annual spring exhibition held at Copenhagen Academy’s Charlottenborg Palace in 1824 and its eventual sale in the auction of a sizeable collection of Lorentzen’s works at Moltkeske Billedgallerie in 1829;[4] thereafter, it fell into obscurity. It is my position that a painting recently sold at auction under the title The German Monk Auerbach in His Workshop Discovers Gunpowder is actually the long-lost pendant of Model School at the Academy.

The pair remained in Lorentzen’s possession until his death.[5] Notations pencilled into the margins of the 1829 auction catalogue (fig. 2), now in the collection of the Danish National Art Library, document the pictures’ separation and the amount paid for each.[6] Only surnames accompany the sale prices. A collector with the patronymic name of “Sivertsen” bought Model School at the Academy, while an individual of noble birth called “Krabbe” purchased The Monk Barthold Schwartz.[7] Later, Model School at the Academy belonged to a Danish ship owner, the Consul General of Austria-Hungary and art enthusiast Johan Hansen (1838–1913), until the Museum of National History acquired the painting in 1934.[8] Further research is needed to address a brief lacuna in the painting’s early provenance, otherwise it is complete.[9]

The Monk Barthold Schwartz, however, disappeared completely from the public eye after the sale of Lorentzen’s paintings. Circumstantial evidence gathered from the Yearbook of Danish Nobility (Danmarks Adels Aarbog) suggests that a Danish army officer, Lieutenant General Ole “Oluf” Krabbe (1789–1864), may have been the purchaser of The Monk Barthold Schwartz at the 1829 auction.[10] The historical subject of gunpowder’s discovery certainly would have interested a military man like Krabbe.[11] A 1971 exhibition catalogue, written by a former curator at Frederiksborg Castle named H. D. Schepelern (1912–2001), provides the only reference to the missing painting after its sale.[12] Model School at the Academy was exhibited at the monographic show C. A. Lorentzen: An Exhibition in the 225th Year of the Painter’s Birth. Its catalogue entry referred to The Monk Barthold Schwartz as its pendant, but neither reproduced an illustration of the picture nor indicated its current location.[13] Clearly, Schepelern’s knowledge of the missing pendant derived from the 1829 auction catalogue, which he cited in his essay.

The Copenhagen-based auction house Bruun Rasmussen sold a painting titled The German Monk Auerbach in His Workshop Discovers Gunpowder in December 2002 without identifying it in the auction catalogue as the companion piece to one of Lorentzen’s best-known works.[14] The painting was bought without fanfare and at a nominal price by an art dealer who has since placed the work with an unidentified collector.[15] After conducting a review of archival material, I have found convincing evidence that Bruun Rasmussen’s painting is in fact The Monk Barthold Schwartz. Similarly titled, The German Monk Auerbach bears Lorentzen’s signature and the year 1818, a creation date that is consistent with documentation of the work’s display at the Charlottenborg exhibition in 1824.[16] The exhibition records and auction catalogues from which Lorentzen’s oeuvre can be established contain no mention of the title given by Bruun Rasmussen. Even more compelling is the match found between a small thumbnail image provided by the Danish auction house (fig. 3),[17] perhaps the only published photograph of the painting in question, and the scene described in the 1829 catalogue:

[Barthold Schwartz] has placed gunpowder on the hearth in his laboratory, weighing it down with stones after ignition. Surprised by the unexpected effect, the monk is shown turning away [from the experiment]. Despite his alarm, [Barthold Schwartz] expresses presence of mind and courage. However, the workshop assistants in the background are most fearful, and the boy in the foreground even covers his face with both hands. Alchemical vessels and equipment are scattered here and there.[18]

Moreover, the dimensions of Model School at the Academy correspond exactly with those provided by Bruun Rasmussen.[19]

Reunited with its companion, The Monk Barthold Schwartz (if known only from a photographic reproduction) complicates the accepted portrayal of Lorentzen and encourages a more nuanced interpretation of Model School at the Academy. The professorial term (1803–28) of Lorentzen, a minor figure in the historical record, overlapped with celebrated painters Nicolai Abildgaard (1743–1809) and Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg (1783–1853). To Denmark’s first art historian, Niels Laurits Høyen (1798–1870), Lorentzen’s tenure represented a period of stagnation at the Academy, which began with the deaths of Jens Juel (b. 1745) in 1802 and Abildgaard in 1809 and ended with Eckersberg’s faculty appointment in 1818. Lorentzen’s style and the perceived simplicity of his compositions led to the formation of a negative posthumous reputation.[20] Model School at the Academy, according to several art historians, serves as a straightforward distillation of his old-fashioned artistic ideology.[21]

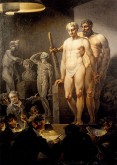

Upon closer examination, however, Lorentzen’s work conveys a critical attitude toward the accepted practices of the Academy. An article by Henrik Bramsen for the newspaper Berlinske Tidende, which has not been cited since it was written in 1971, repositioned Lorentzen as an observant humorist. The essay, coincident with Schepelern’s exhibition, insightfully interprets Lorentzen’s Model School at the Academy as a mockery in the vein of William Hogarth (1697–1764) of the institution’s traditional program.[22] The picture, executed between 1815 and 1820,[23] shows the professor performing his duties as a member of the Academy faculty. According to Bramsen, his facial expression is quite revealing. Lorentzen expresses little enthusiasm for the various facets of artistic instruction on display: the study of antique statuary, as represented in the plaster casts of the Medici Venus and a portrait bust of Faustina the Younger at far left; Andreas Weidenhaupt’s (1738–1805) écorché (fig. 4), an anatomical sculpture of the body’s muscular and skeletal structure; and live models studied under artificial light to the right.[24]

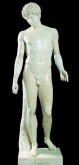

Referring to their exaggerated physiques, Bramsen described the models as “two big, dumb meat mountains.” [25] The art historian was probably alluding to the likelihood that Lorentzen had not observed these idealized figures in the flesh. The 1829 catalogue for the sale at the Moltkeske Billedgallerie identified the source for the bearded model in the background as the Farnese Hercules, while scholar Jan Zahle recently noted a similarity between the figure in the foreground and the Capitoline Antinous (fig. 5).[26] In fact, both statues were displayed prominently in the Academy’s Hall of Plaster Casts at the time of the painting’s execution.[27]

One might expand on Zahle’s identification of the Capitoline Antinous as inspiration for the fair-haired model positioned at the fore. I believe that an illustration found in Johann Daniel Preissler’s popular drawing manual The Theory Invented by Practice . . . (Die durch Theorie erfundene Practic, oder Gründlich-verfasste Reguln, deren man sich als einer Anleitung zu berühmter Künstlere Zeichen-Wercken bestens bedienen kan) (1743–47), which was used at the Copenhagen Academy,[28] also bears a close resemblance to Lorentzen’s model in the muscular physique, loose curls, and orientation (fig. 6).[29] Moreover, the model’s engaged left leg counterbalanced with his right arm fully extended is clearly derived from the Preissler illustration. Lorentzen may have synthesized existing sources in the creation of his work rather than studying his painting’s “live models” from the flesh. Oblivious to Lorentzen’s apparent disinterest, the eager young students in Model School at the Academy absorb his lecture and sketch the two “live” models. Contemporary viewers would have understood these topical references; however, records indicate that he never exhibited the painting publicly. Given the work’s private display, it is unlikely that its message directly brought about change at the Academy.

The Monk Barthold Schwartz, which depicts a monk and alchemist sometimes credited with the independent discovery of gunpowder in medieval Denmark, contrasts with its pendant in the actions and expressions of its excited protagonist and fearful peripheral characters. [30] Here, Schwartz’s apprentices recoil in terror, as opposed to Lorentzen’s keen pupils, who lean forward in their seats. Conceived as a pair, the paintings might address the antithetical relationship between originality and derivation. One picture emphasizes the scientific contributions of a mythologized Dane, while the other displays reliance on foreign artistic models.[31] As previously mentioned, The Monk Barthold Schwartz was exhibited without its pendant at the Academy’s exhibition; yet, the two hung together in the artist’s apartment.

Lorentzen communicates the pendants’ combined meaning through the selected subject matter—the partnership of science and art, a popular theme in the eighteenth century. An earlier, unpublished sketch titled Art and Science Crown a Bust (fig. 7), held in the Royal Collection of Graphic Art at Statens Museum for Kunst, shows allegorical representations of the disciplines celebrating the patronage of a figure, perhaps a bust of Frederik VI (Crown Prince Regent of Denmark until 1808).[32] The goddess Minerva, protector of science and art, stands guard in the background. However, the reading of Lorentzen’s Model School at the Academy offered above indicates that this alliance had weakened at the storied educational institution in the second decade of the nineteenth century.

Professor Eckersberg and his colleague Johan Ludvig Lund (1777–1867) expressed these sentiments when, in April 1822, they proposed an elective course in painting from life during the morning hours of the summer holidays, initiating a pedagogical shift toward realism at the Academy. The idea had been inspired by their training under Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825); however, Eckersberg’s disenchantment with the prescribed curriculum predated his French tuition. A satirical drawing in the Royal Collection of Graphic Art (fig. 8) suggests the pedantry demanded of the Academy’s students in the first decades of the nineteenth century. A professor, whose authority is conveyed with a disproportionately large head and dismayed expression, admonishes young Eckersberg in the presence of his classmates; some laugh at his expense. Following an inscription later added to Satire of the Academy’s Model School, art historians have identified the instructor as Abildgaard; others have suggested it represents Lorentzen.[33] However, I believe it is instructive to compare the caricature to Hans Hansen’s Portrait of Nicolai Dajon (fig. 9). Clearly, the professor more closely resembles Dajon (1769–1828), a student of Jacques-François-Joseph Saly (1717–76) and disciple of Johannes Wiedewelt (1731–1802). Wiedewelt had articulated the Academy’s founding objectives in a concise aesthetic treatise titled Reflections on Taste and the Arts in General (Tanker om Smagen udi Konsterne i Almindelighed) (1762), served as Chair of the Model School (1761–1802), and acted as an intermittent Director of the Academy (1772–77; 1780–89; 1793–95), all the while exerting great influence on the curriculum.[34] Dajon joined the faculty in 1803 to replace the recently deceased Wiedewelt, and by all accounts, he adhered to the classical methods that his mentors championed.[35] He shared the responsibility of teaching the life class with his colleagues and, thus, Eckersberg would have received instruction from him.

Dajon had also served as Director of the Academy from 1818 until 1821,[36] during the very same period that Lorentzen is believed to have composed the pair under consideration. Therefore, it seems likely that Model School at the Academy and its pendant The Monk Barthold Schwartz examine the ossified curriculum of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts through a critical lens, and signal the paradigm shift that would soon follow.

Leslie Anne Anderson-Perkins

landerson[at]gc.cuny.edu

This article developed from a piece I wrote for Statens Museum for Kunst’s online art history resource Art Stories (Kunsthistorier), which addresses the popular motif of the artist and the live model in nineteenth-century Danish painting. The following people and organizations allowed me to realize this project. I am particularly grateful to Kasper Monrad, who encouraged my research and made valuable suggestions along the way. Thomas Lyngby and Morten la Cour graciously invited me to their institutions and granted access to paintings by Lorentzen. My archival investigation in Denmark was facilitated by Patrick Kragelund, Jens Toft, and Frederik Tygstrup; and it was supported by the Danish-American Fulbright Commission, the American-Scandinavian Foundation, and the Society for the Advancement of Scandinavian Study. Thor Mednick and Michelle Facos read my manuscript and offered thoughtful comments. Finally, I would like to thank Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, Robert Alvin Adler, and Isabel Taube for their assistance in preparing this article for publication.

All translations into English are mine.

[1] Christen Købke and Martinus Rørbye began their private studies with Lorentzen before seeking instruction from Eckersberg. Such images of artistic practice include Bendz’s well-known painting The Life Class at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (1826) and Rørbye’s Artist Drawing a Model (from a sketchbook ca. 1825–26), both held at Denmark’s Statens Museum for Kunst. Købke depicted scenes from the Academy’s Hall of Plaster Casts (1830; Hirschsprung Collection, Copenhagen), plein air sketching excursions (1832; Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen), and Eckersberg’s private atelier, such as the portrait of Wilhelm Marstrand (ca. 1829; Museum of National History, Frederiksborg Castle, Hillerød).

[2] The Dane Andreas Andersen Feldborg (1782–1838) published a description of his homeland for an English-speaking audience. In the three volume text, Denmark Delineated, he mentions Professor Lorentzen’s painting-room and collection at Charlottenborg, promoting it as a space that “will amply reward the curiosity of the viewer.” Feldborg, Denmark Delineated; or, Sketches of the Present State of that Country (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd and D. Lizars, 1824), 13.

[3] The catalogue entry for Model School at the Academy in the 1829 sale of Lorentzen’s works refers to the painting as a “companion piece to the above” (“sidestykke til forrige”), which is The Monk Barthold Schwartz, Inventor of Gun Powder. Fortegnelse over en Samling originale Malerier af afdöde Professor ved Kunstacademiet i Kjöbenhavn Christian August Lorentzen, (Copenhagen, 1829), 6 [Inventory of a collection of original paintings owned by the deceased Copenhagen Academy professor Christian August Lorentzen]; hereafter, Auction of Paintings Owned by Lorentzen, Copenhagen, 1829. The sale was held at the Moltke family’s private collection called the the Moltke Picture Gallery or the Moltke Painting Collection (Moltkiske Billedgallerie), which was an exhibition space open to the public one day each week in the nineteenth century.

[4] Fortegnelse over de ved det Kongelige Academie for de skiönne Kunster offentligen udstillede Kunstværker [List of the exhibited artworks at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts] (Copenhagen, 1824), 3; hereafter, Charlottenborg Exhibition, 1824; and Auction of Paintings Owned by Lorentzen, Copenhagen 1829, 6.

[5] It is not stated explicitly in the 1829 auction catalogue of the Moltkiske Billedgallerie that it was his estate sale. Thus, I will not refer to it as such. However, the Danish National Art Library, which owns several copies of this publication, records it as a sale of Lorentzen’s “estate” (or “bo”). At least one printed version of the 1829 catalogue is titled Fortegnelse over nogle originale Malerier af afdøde Professor Lorentzen, som han har ønsket ikke maatte vorde adskilte [A Collection of original paintings by the late professor Lorentzen that he had wished remain intact]; hereafter, Collection Lorentzen wished to remain intact, Copenhagen, 1829. An official estate sale had taken place in August, 1828 at Charlottenborg. I believe the paintings sold in 1829 had belonged to Lorentzen’s estate, and that the executor’s inability to find a buyer for the entire collection intact, as was Lorentzen’s apparent wish, may have prompted this second sale. Auction of Paintings Owned by Lorentzen, Copenhagen, 1829; and Collection Lorentzen wished to remain intact, Copenhagen, 1829.

[6] Auction of Paintings Owned by Lorentzen, Copenhagen, 1829, 6. Model School at the Academy was purchased for thirty rigsbankdaler and The Monk Barthold Schwartz sold for thirty-two. The rigsbankdaler unit of currency was renamed “rigsdaler” in 1854.

[7] Ibid.

[8] H. D. Schepelern, C. A. Lorentzen: Udstilling i 225-året for malerens fødsel, exh. cat. (Copenhagen: Thorvaldsens Museum, 1971), 47. Model School at the Academy was numbered “1062” in the inventory of Hansen’s sizeable collection.

[9] The exact date of Hansen’s purchase is unknown and it was not provided in the published inventory of his works. It was certainly before 1913, when he died.

[10] Dansk Adelsforening, Danmarks Adels Aarbog (Copenhagen: Dansk Adelsforening), s.v., “Krabbe af Damsgaard,” published every 3 years, and whose editions of 1938 and 1988 I consulted, provides the genealogies of Danish and Norwegian noble families. Based on his age at the time of sale and his residency in Copenhagen, Ole “Oluf” Krabbe emerges as the most likely purchaser of the painting. It should be noted that The Monk Barthold Schwartz was the only work acquired by Krabbe at the auction, and it may have had special significance to the buyer, whereas Model School at the Academy was one of several paintings purchased by “Sivertsen.”

[11] Dr. Patrick Kragelund, Director of the Danish National Art Library, made this astute observation when I discussed my research with him in May 2013.

[12] Schepelern, C. A. Lorentzen, 47.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Arne Bruun Rasmussen, “Lot 1749,” in Danish and International Paintings, Drawings and Prints (December 2002). Literature on the topic of gunpowder’s invention offers several names and nationalities of proposed inventors. J. R. Partington, A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 94–95.

[15] Kasper Nielsen, e-mail message to author, April 14, 2013.

[16] Rasmussen, “Lot 1749”; and Charlottenborg Exhibition, 1824, 3. The Monk Barthold Schwartz was one of six paintings exhibited by Lorentzen at the Academy’s spring exhibition in 1824. He had not shown any of his works in the 1818 exhibition. Ibid; and Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Fortegnelse over de ved det Kongelige Academie for de skiönne Kunster offentligen udstillede Kunstsager [List of the exhibited artworks at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts] (Copenhagen, 1818).

[17] Rasmussen, “Lot 1749.”

[18] “Paa Skorstenen i sit Laboratorium har han lagt endeel Krudt, og betynget det med Stene; dette har han just antændt. Overrasket ved den uventede Virkning, sees Munken vel at vende sig om, dog udtrykker hans Mine Aandsnærværelse og Mod, da derimod tvende i Baggrunden arbeidende Medhjelpere vise den største Skræk, ligesom og en Dreng i Forgrunden tildækker Ansigtet med begge Hænder. Rundtom ligger adspredt chemiske Kar og Apparater.” Auction of Paintings Owned by Lorentzen, Copenhagen, 1829, 6.

[19] Per the 1829 estate auction catalogue, the dimensions of the pendants are the same: “33 T[omme] h[øjde], 29 T[omme] b[redde].” The measurements are in “thumbs” (“tommer”), similar to inches today. Bruun Rasmussen’s The German Monk Auerbach is 86 x 61 centimeters; Denmark’s Museum of National History records the dimensions as 87 x 61 centimeters. Auction of Paintings Owned by Lorentzen, Copenhagen, 1829, 6.

[20] Poul Gammelbo refers to the negative reception of Lorentzen’s works by art historians Høyen, Karl Madsen (1855–1938), and Henrik Bramsen (1908–2002). Gammelbo, “Barnlig skaberglæde er ingen ringe kunstneregenskab,” Newspaper Clipping, March 1, 1971, Lorentzen File, Hjalmar Bruhn Collection, Danmarks Kunstbibliotek, Copenhagen, Denmark.

[21] Schepelern, C. A. Lorentzen, 47; Jan Zahle, “Christian August Lorentzen, Akademisk malerskole, ca. 1815–20,” in Spejlinger i Gips, ed. Pontus Kjerrman, exh. cat. (Copenhagen: Forfatterne og Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademis Billedkunstkolers, 2004), 140.

[22] Henrik Bramsen, “Maler, professor, komediant,” Berlingske Tidende, February 26, 1971. Bramsen’s article followed two publications by H. D. Schepelern, which portrayed Lorentzen as an important figure in the development of genre painting in Denmark. The attempt to resurrect Lorentzen, which was initiated by Schepelern, proved unsuccessful in the forty years following these publications. H. D. Schepelern, “Professor Chr. August Lorentzen—maleren fra Sønderborg,” Sønderjysk Månedsskrift, November 1971, 409–13; and H. D. Schepelern, C. A. Lorentzen.

[23] It is possible that Model School at the Academy was left undated because Lorentzen did not want to express dissatisfaction with the Academy’s leadership at the time of execution. As the article proposes, the creation date likely coincides with the appointment of Nicolai Dajon as Director (1818–21). Perhaps because the subject matter is derived from legend, and not the artist’s life, Lorentzen decided to date The Monk Barthold Schwartz.

[24] Jan Zahle suggests that the Roman bust depicts a young Marcus Aurelius. However, the bust appears more closely related to that of Faustina the Younger, which was available as a plaster cast in the Academy’s collection. Zahle, “Christian August Lorentzen,” 140.

[25] Bramsen, “Maler, professor, komediant.” Bramsen’s visual description in Danish reads: “to store, dumme kødbjerge.”

[26] Auction of Paintings Owned by Lorentzen, Copenhagen, 1829, 6–7; Zahle, “Christian August Lorentzen,” 140.

[27] Published inventories of the plaster cast collection document the presence of these sculptures. Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Ny Fortegnelse over Marmor- og Gips-Figurerne, samt Receptions-Stykkerne og flere Konstsager i det Kongelige Maler- Billedhugger- og Bygnings-Academie paa Charlottenborg med hosföyet kort Forklaring over de betydeligste Poster [New inventory of marble and plaster figures, as well as reception pieces and various art works of the Royal Painting-Sculpture-and Architecture Academy at Charlottenborg, with a brief explanation of the most significant items] (Copenhagen, 1793), 2; the inventory, with the same title, for the year 1805, at pg. 4; and the inventory, with the same title, for the year 1809, at pg. 4.

[28] Erik Fischer, Tegninger af C. W. Eckersberg (Copenhagen: Den Kgl. Kobberstiksamling, Statens Museum for Kunst, 1983), 153.

[29] Johann Daniel Preissler, Die durch Theorie erfundene Practic, oder Gründlich-verfasste Reguln deren man sich als einer Anleitung zu berühmter Künstlere Zeichen-Wercken bestens bedienen kan (Nuremburg, 1743–47).

[30] The Danish origin of the monk and the year of his scientific discovery are dubious. However, several published accounts beginning with Janssen ab Almeloveen (1657–1712) suggest that this version of the mythologized monk’s biography was popular. He is more often identified as German. Partington, History of Greek Fire, 94.

[31] The écorché, while created by the Dane Andreas Weidenhaupt, is an artistic tool that became popular at the French Academy. Similar anatomical figure studies date to the Renaissance. The écorché, like plaster casts of antique statuary in Model School at the Academy, represents an artistic methodology developed abroad.

[32] This work is related to a finished composition depicting the bust of King Frederik VI being crowned with a laurel wreath (n.d.; Museum of National History, Frederiksborg Castle, Hillerød).

[33] An inscription on the verso of the drawing labels the scenes as “Abildgaard corrects Eckersberg.” However, the inscription was made by an unknown hand, perhaps at a much later date. Presumably, the identification is based on the fact that Eckersberg studied under Abildgaard, and that Eckersberg’s son later discussed openly the contentious nature of their relationship. Kasper Monrad, conversation with the author, May 3, 2013.

[34] J. W[iedewelt], Tanker om Smagen udi Konsterne i Almindelighed (Copenhagen, 1762); Marjatta Nielsen, “An Introduction to the Life and Work of Johannes Wiedewelt,” in Johannes Wiedewelt: A Danish Artist in Search of the Past, Shaping the Future, ed. Marjatta Nielsen and Annette Rathje (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2011), 16; and Anneli Fuchs and Emma Salling, eds., Kunstakademiet, 1754–2004 (Copenhagen: The Royal Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture Publishers, 2004), 3:14.

[35] Nielsen, “Life and Work of Johannes Wiedewelt,” 29; Jan Zahle, “Wiedewelt and Plaster Casts in Copenhagen, 1744–1802,” in Nielsen and Rathje, Johannes Wiedewelt: A Danish Artist, 131.

[36] For a list of the Academy’s directors, faculty, and members, refer to Fuchs and Salling, Kunstakademiet, 1754–2004, 3:13–29.