The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

“In the Park”: Lewis Miller’s Chronicle of American Landscape at Mid-Century

with Emily Pugh, Jessica Ruse, and Courtney Tompkins

II. Lewis Miller, ”Guide to Central Park”: A fully annotated, digital facsimile

[III. Lewis Miller’s View of American Landscape (Therese O’Malley)]

III. Lewis Miller’s View of American Landscape

Therese O’Malley

Historians have long considered Lewis Miller’s corpus of two thousand drawings of nineteenth-century America as eyewitness accounts and, thus, a valuable source of documentation of daily life, and the vernacular and cultural landscape (fig. 1). Miller was an extraordinary chronicler, largely because of his life span, 1796-1882: his drawings date from the early republic, through the Civil War, to the Centennial. Although Miller has earned a special status as a folk artist—given his presence throughout most of the first American century— there has been little investigation into the veracity or perspective of his record. Donald A. Shelley, author of the major text on Miller, expresses the standard assessment: “Perhaps the greatest contribution of Miller’s drawings is their realistic accuracy, hence their value to the historian from a purely documentary point of view.”[1] Writing in the 1930s, Preston and Eleanor Barba argued that Miller’s reflections as “a primitive artist,” offered not only views of historic artifacts, but also insight into past experience and society.[2] A closer look at Miller, and at his work on its own terms and not simply as documentation, is overdue. This essay seeks to discover Lewis Miller’s “point of view” beyond the role of cultural reporter, and to see him as witness to a dynamic period of social and cultural transformation, and exponent of contemporary aesthetic sensibilities.

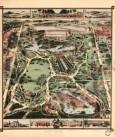

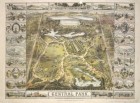

This study turns mostly on a single album that Miller made, perhaps in the 1860s, perhaps in the course of the Civil War. This little-known object of fifty-four pages of ink and watercolor drawings, now in the Henry Ford Museum, is a “guide” to what he called “the Central Park.”[3] New York City’s great park, the first urban landscape park in America, was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in 1857 and opened in 1860 (figs. 2, 3). When I first started to study this diminutive album, I wondered what insight it could offer me, a landscape historian, into the experience of a visitor to the brand-new Central Park, at a time overshadowed by the crisis of the Civil War. We have numerous prints, stereograph photos, and souvenirs books of the Park. But this was a unique voice, a folk artist’s version of this urban masterpiece. What I discovered challenged my understanding not of the Park, but of Lewis Miller himself, and made me question the shaping and complexity of his visual expression.

The original order of the album leaves is unknown: like all Miller’s work, it has been bound and rebound (fig. 4).[4] Most leaves in this album, again like so much of Miller’s extant drawings, have inscriptions of verse, prayers, botanical names, and concordances of German and English words. (See Kathryn Barush’s essay “A Pilgrim in the Park: Sacred Space in Lewis Miller’s “Guide to Central Park” in this issue of Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide.).[5] The album’s unusual compilation of texts and images raises questions of representation that impel us to question the repeated identification of Miller as a folk artist. John Michael Vlach has defined the folk artist as a member of a specific community whose work reflects that community’s ethos.[6] This essay resists that definition for Miller, whose work does not present issues of fidelity to any one collective imagination, in particular, that of the Pennsylvania German American society to which he was born. Once we better understand the context of his work and his working method, it will be possible to move away from that reductive category for Miller. Miller’s little manuscript may not be in and of itself a significant work of art, but it is an indicator of deeper trends transforming America in Miller’s lifetime, including urbanization, innovations in technology, the changing definition of public space, and the expansion and penetration of print media—all signs of an evolving modernity in America.[7]

Long before Central Park, Miller was a traveler (fig. 5). It is useful consider what it meant to be able to travel freely in the early and mid-nineteenth century. The right to travel among the various states was one of the first individual freedoms established by the Articles of Confederation. Scholars such as John D. Cox have argued that as it was denied to slaves, bondsmen, and criminals, travel was symbolic of American freedom and identity. Thus, travel writing and sketching, such as Miller’s, and in general in early America, celebrated that freedom of movement and expressed national identity.[8] In addition to the movement of people, the movement of ideas and information though modern media is critical to understanding that moment in the history of the places Miller drew, and Miller himself.

Lewis Miller, Regional Artist or Picturesque Traveler?

Lewis Miller was rediscovered as a historic figure in the early twentieth century, in the wake of moments of national nostalgia and the emergence of folk-art collecting. Frances Pohl, in her social history of American art, wrote that “the interest in American folk art was helped by . . . the promotion of Americana by the art world and the federal government throughout the 1930s. Artists and critics looked for the roots of Modernism in the world of untutored artists.”[9] Based on his drawings of quotidian life, Miller has been repeatedly described as an authentic regionalist artist—claimed by both Pennsylvania and Virginia as their own (fig. 6).[10] In his 1950 book, American Painting, Virgil Barker wrote: “Both in spirit and in technique Miller’s work was an attractively natural product of a regional society in which the semi-pictorial craft of fractur had been practised since before he was born. . . . As pictures the colored sketches document the amateur who had no technical qualms whatever and who therefore was singularly self-sufficient.”[11] While one may question whether any visual artist is ever truly self-sufficient, this essay provides evidence that Lewis Miller, in terms of his absorption of current visual culture, certainly was not.

One drawing, inscribed “Lynchburg-_negro dance, August 18th, 1853,” (fig. 7) serves to illustrate that some of Miller’s most famous drawings were, if not inspired by, at least influenced by other images made available through widely disseminated print culture. Miller must have seen the anti-abolitionist broadside of 1850, portraying a stereotypical vision of the life of southern enslaved people (fig. 8). If one can easily find visual parallels between Miller’s drawing and printed antecedents, such as this broadside, it is clear that rather than being bound by one ethnic visual culture, he absorbed a wide range of influence. Yet scholars continue to read his drawing as eyewitness accounts.

A study of the Central Park guidebook helps to show that even as an amateur or untutored artist, Miller was clearly aware of artistic vocabulary and conventions (figs. 9, 10). We only have to read his obituary, written by his friend H. L. Fisher, to learn that Miller was a “lover of the sublime . . . an amateur of no mean skills in the arts of rustic drawing.” From this statement, we can assume that Miller had some acquaintance with artistic conventions. The question remains how he came to know them. Fisher also wrote that Miller made “quaint caricatures” of local people that “neither Punch, Puck nor Harper could rival.” Fisher’s reference to the leading illustrated periodicals suggests a potential source for Miller’s rustically illustrated manuscript folios.[12] It might be impossible to document precisely Miller’s visual and artistic influences, but this paper will show how the emerging visual culture of tourism and related publishing seems to have shaped Miller’s work.

Recently, scholars have seen Miller, living as he did between York, Pennsylvania, and Christiansburg, Virginia, as a conventional first-generation German American, experiencing the gradual assimilation of his mother culture—specifically its language, customs, art, and architecture—into the dominant Anglo-American culture.[13] For example, Donald Linebaugh used Miller’s sketches, together with archeological remains, to trace a chronology of cultural changes and exchanges specifically in the study of vernacular architecture.[14] Art historians Mary Black and Jean Lipman wrote that while Miller’s work provided “homely details” of daily life otherwise lost, it also, importantly, represented the aesthetic endeavors of a rising middle class (fig. 11).[15]

How and why did the new Central Park, an elite, high-style yet forward-looking artistic and social construct, attract the attention and efforts of the folksy sixty-year old Pennsylvanian? Although Miller’s book was a singular, private production, and Central Park was the ultimate public art form, each can shed light upon the other’s purpose and reception. One way to explain Miller’s choice of topic, Central Park, is to look earlier in his life and consider the subjects of his previous artistic endeavors. Natural and historic sites were themes that remained vivid for him throughout his life. Miller’s sketches are filled with the sites he claims to have visited both abroad and in America. His European tour of 1840-41 came at a time when Americans outside the gentry class were beginning to go abroad, whether to seek their roots or for self-edification (fig. 12). In Miller’s case, it was no doubt for both reasons. In a memoir written possibly at the end of his trip, he exclaimed: “My tour of Europe was A School to Me.”[16] In contrast to the European grand tour, which had existed in some form since pilgrimages in the medieval period, the American tour route was only gradually being defined. What is of particular note is where he went and what he saw as he traveled in the United States, and why he might have chosen these sites. Miller was traveling along established routes of a burgeoning tourism industry. This essay argues that he was influenced by the new pictorial press and travel guide phenomenon that had begun in the 1820s but expanded significantly after 1840.[17] (For a discussion of Miller as a religious traveler, see Barush’s essay “A Pilgrim in the Park.”)

Sites associated with historical events or figures drew Miller’s attention, such as George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Virginia (fig. 13), which was a pilgrimage site even in the president’s lifetime. The Bunker Hill monument (built 1842–43) and Benjamin Franklin statue (erected 1856), both in Boston, were recent memorials to the Revolution (fig. 14). Miller drew the Natural Bridge in the Blue Mountains of Virginia at least three times (fig. 15).[18] In addition to these historic and natural wonders, Miller seems to have been drawn to current, new exemplars of landscape design such as rural cemeteries and public squares. He drew Prospect Hill Cemetery (dedicated 1849; fig. 16) in his hometown of York, as well as the very popular Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia (established 1836; ).

Warm springs, baths, and spas had become increasingly successful tourist destinations since the colonial period. Saratoga Springs in New York defined this genre through its innovative self-promotion through guidebooks.[19] Miller depicts Yellow Sulphur Springs, the spa town closest to where he lived while visiting his brothers in Montgomery County, Virginia (fig. 18). Many of the places Miller recorded in his drawings were topical enough to be discussed and illustrated in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine (August, 1855; fig. 19), and in print series such as Edward Beyer’s Album of Virginia, (1858; fig. 20). Thus, Miller was familiar with contemporary, even fashionable and popular culture that was not limited to his local community at all, which further distances him from the category of folk artist. In fact, his taste for picturesque landscape in design and romantic literary arts links him to national and international currents of taste.

Miller depicts places of some prestige or significance that were useful in defining what was authentically American, aesthetically important, or intellectually valuable for American culture. These sites were identified as the new nation’s rivals to the great European monumental sites and sights. Miller clearly states this idea in his “Guide to Central Park.” In a scene in which a couple is seated under a rustic arbor, Miller wrote: “Still farther back, and down to the lake, has Some points – that transferred to canvas, would bear comparison with the boasted Scenery of the old world” (fig. 21).[20]

With this background, it is not surprising that Miller chose to make an album about the most monumental and innovative undertaking in public space and landscape aesthetics of his era, Central Park in New York. With his own version of a guidebook, Miller bore witness to the birth of the public park movement in America. Within the next twenty years, every major city in the nation had at least one Olmstedian public park.

Upon its opening, the Park was an immediate success. Within two years, it had almost two million visitors per annum (fig. 22).[21] This is not the place to rehearse the whole history of the building and evolution of Central Park, a subject with a rich body of literature.[22] It is, however, useful to look at it in comparison with one other park of the same period, to see how each strata of society had its preferred public sites for different purposes. According to social historians Roy Rozenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, Jones Wood was a park where many ethnic groups, especially Germans and Irish, retreated for outdoor exercise and socializing (fig. 23).[23] It was a place where immigrants went for summer excursions and festivals, and where they could listen and dance to band music. German immigrants in particular thought of Jones Wood as a place where they could retain their cultural traditions.[24] In spite of the popularity of Jones Wood and the links to the German community, we have no trace of Miller going there. Instead, he focused on Central Park, where German or Irish immigrants were often unwelcome. They were excoriated in the media for not behaving in a way designated by Olmsted and Park commissioners as suitable for the new Park. As scholars have written, Central Park was not a place for republican equality, but for the elevation of public sensibilities.[25] There was a decorum to Park behavior that was defined by posted rules and enforced by police called park keepers, both of which Miller captured in several drawings (fig. 24). Central Park’s strict controls were commented upon in the press and parodied in cartoons (fig. 25).

Clearly, Olmsted’s vision demanded a different use of this space than that at Jones Woods. We can see from his “Guide to Central Park” that while Miller was not among the elite in carriages or on horseback, neither was he among the unrefined lower classes. He seems to represent a middle class of visitors—walkers—who carried guidebooks and who could afford to enjoy the aestheticized landscape and natural world.

Before looking closely at Miller’s “Guide,” a word of caution is needed regarding the chronology and identification of his drawings. It is quite difficult to date much of Miller’s work, in spite of its relationship to actual events or even the presence of dates on the work. A case in point is one drawing of the Crystal Palace from the Great Exhibition in London (fig. 26) that scholars generally associate with all his other views from sites he is assumed to have visited while abroad in 1840-41.[26] The Crystal Palace, however, was not built until a full decade later.[27] A visual comparison with an illustration from Harper’s (fig. 27) suggests that Miller copied it, cutting away the central section, condensing the width, and covering the disparity with trees in order to fit the very wide original image on his sheet.

With this new understanding of Miller’s working method, even a cursory search for visual sources revealed many potential models for his drawings. Another comparison, Miller’s illustration of the Natural Bridge, and one from Harper’s, underscores the proposition that printed illustrations helped Miller remember his subjects, and to compose subjects which he may never have visited (figs. 28, 29). This drawing is not an exact copy, but a paraphrase rather than metaphrase, or, one might say, Miller’s translation into his own idiom. Miller relied upon a combination of field sketches and printed images from guidebooks and prints to compose the drawings that have come down to us. It should be mentioned that throughout his extant oeuvre, each page is a finished drawing, showing little sign of sketching, erasure, or preparatory stages. This is true of the inscriptions as well, which, clearly, are copied. Finally, two more drawings of European sites from Miller’s album “Landscape’s [sic] In the State of Virginia,” in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, provide the most direct evidence of Miller’s copying from published sources. These are two of many drawings that have never before been identified as anything other than “Miller’s European sketches.”[28] The original prints on which Miller based his work are found in picturesque travel books from 1836 and 1840 (figs. 30, 31, 32, 33).[29]

With this new awareness of Miller’s working method, we can examine his “Guide” from a fresh perspective. Two dates appear in the album: on what is bound as page 16, Miller inscribed the drawing of the entrance at Eighth Avenue with, “New York, 1864” (fig. 34). On page 40, which shows the Bell Tower and statue of “Commerce,” Miller inscribed: “May 23, 1867, I was in the park” (fig. 35). It cannot be determined with any certainty when Miller made his book. We can, however, ascertain what point in the Park’s construction he represented because at least one structure, the Bell Tower, was temporary and replaced in 1869.[30] Thus, he portrays Central Park within the first decade of its twenty years of construction.

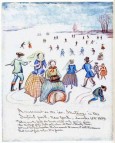

We can infer from dated drawings that Miller had been to New York City at least twice, if not three times before. His first drawing is dated 1840, when he sailed from Castle Gardens in lower Manhattan for Europe. He dates a drawing of the great Croton Reservoir at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue as October, 1842 (fig. 36).[31] This system, which would supply drinking water to the whole city, was a monumental civic achievement in terms of building construction and technology. Another sketch inscribed “Skateing in the Senterel Park, december 15th, 1859,” (fig. 37) suggests a winter visit, which would be at the earliest point in the Park’s existence but before most of the Park features in his guide were constructed. Ice skating was a new recreation for women, and was quickly becoming a fad.[32] Skating, horseback riding, and outdoor concerts were new points of entry for women into the public sphere, and these activities were well illustrated in the pictorial press. Harper’s (1861) reported:

The excellent facilities which the frozen waters of the lake afford for the noble exercise of skating have of late, given such a marvelous impetus to that merry sport as to have made it one of the most attractive social features of winter life in the city (fig. 38).[33]

Winslow Homer’s first drawing of life in New York for Harper’s Weekly was a skating scene in Central Park (fig. 39) and Currier and Ives made one of the early prints of it as well (fig. 40).[34] With this kind of attention in the press, Central Park was immediately elevated to a must-see site on the American tourist circuit.[35] This Park’s prestige was caught up in the success of illustrated newspapers, magazines and guide books. New York City was the center of this industry and the city’s attractions were, not surprisingly, popular subjects.[36] During the late 1850s, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and then Harper’s Weekly pioneered a process of wood engraving that enabled the inclusion of illustrations within the text (fig. 41). With rapid mechanical improvements and innovations such as electrotyping, this period experienced unprecedented mass production of illustrated periodicals and books. These advances occurred in the period before the Civil War and the opening of Central Park, and these two disparate topics became frequent pictorial and literary subjects for the press (figs. 42, 43).

Miller’s guidebook takes on new significance when seen in a context of a constellation of textual and literary sources, both American and foreign. The Park’s fame went well beyond the United States, showing up in European periodicals (fig. 44). This context helps one see Miller at mid-century as a person who is up to date with what is happening at a far greater scale than the regional or local. This was largely due to the penetration of print media and the explosion of visual information, which has been referred to in the period between 1825 and the Civil War as “the currency of culture.”[37]

Miller’s “Guide” must have been shaped by the influx of popular visualizations of the much-touted park. Study of some of the most popular guides and illustrated journals suggests that Miller was very much aware not only of the wood engravings, but also of that other new inexpensive technology that exploded in the period of the Civil War, photography.

The Impact of Printed Guides’ Views of Central Park on Louis Miller’s “Guide”

Among published sources, one guidebook to Central Park that could have been available to Miller stands out in a comparison with his “Guide”: The Central Park: Photographed, by W. H. Guild Jr., with descriptions and a Historical Sketch by Fred B. Perkins, published in New York in 1864 (fig. 45). Miller inscribes that same year, 1864, on what might have been his title page (bound as page 16; see fig. 34). The books share several themes in both text and image.[38] Perkins and Guild’s book is directed not at the equestrian or carriage set, but rather those who walked and took the streetcar. It opens and closes with directions to find the correct “red cars” or streetcars from downtown. The preface is written in a mode that had become convention in guidebooks, one in which the author is witness to the scenes depicted:

The descriptions in this book were written in the presence of the scenes described. They are set down as if in the course of a walk about the Park, and as if orally delivered to a companion, with the pictures in hand meanwhile. Various things are thus told which the pictures do not show, but which may be seen at the places mentioned, or were seen there; and the book becomes, to a certain extent, a guide to the Park, as well as a series of descriptions of it.[39]

Similarly, Miller, on the title page for his guide, claims, “I was in the Park,” and declares the work to be his own “original sketches of drawings.” This eyewitness conceit was commonplace in both written and visual works, as seen in the subtitle “from nature,” meaning as seen by the artist, on G. W. Fasal’s 1862 series of lithographs, Central Park Album.[40] Another example is the claim by artist C. H. Wells that his original drawing for an 1853 print of Mount Vernon, was made “on the spot and in colors.”[41] Such a statement is meant to attest to the faithfulness of the images and texts. It was a conceit used by Miller his whole life. On one of Miller’s late works, he wrote:

From the year 1799-1870.

All of this Pictures Containing in this Book.

Search and Examin.The are true Sketches

I myself being there upon the places and Spot and

Put down what happened (fig. 46).[42]

On ten pages of his guide to Central Park, Miller illustrates himself sketching (fig. 47), a visual correlative to stating one’s presence as eyewitness in text. In a long- established convention, the spectator looks over the shoulder of the artist to see what the artist sees (figs. 48, 49). In ten other sketches, a park visitor/Miller is pointing to something in the scene as if directing the viewer’s gaze and attention (fig. 50). Perkins uses the equivalent trope of speaking in the first person, or explaining that what the camera has not captured the author will describe to you as you walk together: “Reader, suppose yourself standing with me.”[43]

A second shared theme, that of free access—the publicness of the new Park—also appears on what might have been the title page of Miller’s manuscript (see fig. 34): “The Entrance free,” is inscribed across the page. In his preface, Perkins on this same idea: “The Park is what I have already called it—a great democratic pleasure-ground . . . To be a visitor is to exercise ownership in it. It is his who will but enter and enjoy.”[44] Perkins praises the artistic value of the Park, and all connected to it: “The merit of first suggesting this great public work . . . belongs to the thoughtful and musical Poet, the practical, clear-headed and strong-minded editor and fearless and thorough-going friend of humanity and freedom, William Cullen Bryant.”[45] Bryant, renowned for his poems of natural scenery, meditations of the American landscape, and travel accounts, was among the first to propose the city park and was deeply involved in its founding.[46] Miller quotes Bryant’s poetry several times in his “Guide” (fig. 51).

“In the Park,” a phrase used by Perkins also, is repeated thirteen times in Miller’s text accompanying his sketches. While making the claim for the authenticity of his experience, the phrase becomes almost a musical refrain (fig. 52). It captures the sense of entering, walking, experiencing the Park with all the senses. Sight, smell, touch, taste and certainly sounds are evoked in both texts: Perkins writes about, “the subtler pleasures of music.” Miller depicts musicians and writes titles and lyrics of songs throughout the guide. (fig. 53). He also proclaims: “The birds pour forth their notes of Spring, in Sunshine and in Shade, they Sing Sweet Singers, ever Sing.”[47] For the sense of taste, Miller shows picnickers eating, but adds a warning: “Enough is a feast, too much a vanity” (fig. 54).

The theme of walking, a constant in Miller’s life and work, is also in guide: “Not only does the poor man have what ever the rich man can, in the Park, but much that he cannot. Hundreds of sweet, quiet nooks, pleasant corners of water scenery, little shade bowers, higher ‘coignes of vantage,’ accurately chosen view-points – all these must be walked to. Nature will be wooed in humility” (fig. 55).[48]

Perkins addresses the walker upon entering the Park:

Here we are at the Sixth Avenue entrance . . . faithful to the pure democracy of their doctrines, the best, most various, and most numerous views, lie along the paths of the walkers.[49]

(See Kathryn Barush’s essay “A Pilgrim in the Park” in this issue for more on Lewis Miller as a walker and pilgrim.)

Miller’s and Perkins and Guild’s guidebooks have similar scope: Miller’s has 54 plates, Perkins and Guild’s, 51. The overlap of scenes is telling; more than forty are shared, some quite closely in format and framing. A comparison of four scenes in the Park will illustrate how Miller’s drawings echo the Perkins and Guild guidebook. First, a comparison of the views of the Umbrella, a rustic seat in the Ramble near Bow Bridge designed by Calvert Vaux, reveals them to be quite similar in foregrounding the seat (fig. 56, fig. 57). Perkins points out in his text that one should be able to see the Terrace beyond, although it is not visible in the photograph.[50] Miller includes the Terrace in his drawing and writes: “From this place, A fine view of the Lake and Basin and Basement, on the opposite side.” It is almost as if Miller and Perkins are in conversation with each other.

Second, in their parallel views of the Indian Cave, Miller seems to have illustrated (fig. 58) two figures who Perkins described in his text as “phantoms”:

Here is something which the photograph does not show. While we gaze, suddenly a gay group of youths and maidens appear in the furthest depths of the cave; passing over as phantoms glide across a sorcerer’s mirror they disappear at the other side. Phantoms are no part of the Park zoology, however, so far as we know; let us go and see.[51] (fig. 59)

Miller’s drawing captures the ethereal appearance of a “maiden” and “youth” in the cave, shimmering from the light reflected by the lake. Third, in his view of the Bell Tower, in addition to the similar point of view, Miller’s watercolor and ink drawing is almost monochromatic in a sepia color that emulates the tonality of Guild’s photograph (fig. 60, fig. 61). Finally, the Music Pavilion (fig. 62, fig. 63), with its cast iron filigree design, was the centerpiece of the hugely popular concert program. Perkins extols the “cupola, dark blue, sprinkled with gilt stars, [which] is girdled with a coronet of larger stars . . . and one great gilded star crowns the tip of the finial.”[52], and Miller supplies the color in his version. These are just a few of the many comparisons that can be made between the two guides.

Many of Miller’s drawings also resemble views of Central Park from other sources in the early 1860s, a time when the Park was a frequent topic in papers and magazines. He also borrowed motifs from sources unrelated to the publication legacy of Central Park. Just one example will serve to illustrate Miller’s reliance upon the popular pictorial press. A lady on horseback appears, with slight variations, three times in Miller’s guide, depicted in high style riding outfit with fluttering veil, usually on a rearing horse (fig. 64, fig. 65, and see fig. 34). The figure is often closely framed or foregrounded. It is a motif that appears in other drawings by Miller outside the Central Park album. They seem to derive from fashion plates, a feature started by Godey’s Ladies Magazine (the most popular magazine in the antebellum period) and soon emulated by Harper’s and Frank Leslie’s because of the feature’s success (figs. 66, 67). Thomas Nast used this lady-equestrian motif for his two-page spread Central Park Winter for Harper’s Weekly (fig. 68). A hand-colored lithograph probably published in 1837, of Queen Victoria on Horseback in the Royal Park at Windsor (fig. 69) is a possible earlier source.

Miller’s Central Park views may sometimes seem at odds with one another, in that they are both nostalgic and progressive in outlook. He repeatedly draws the modern engineering achievements of the Park—its sixteen beautiful new bridges and arches, for example, which were built to support Olmsted and Vaux’s ingenious circulation system in which pedestrian, bridal, and carriage traffic were separated from each other and from the transverse crosstown traffic (fig. 70).

Similarly, on a page inscribed with a quotation from Shakespeare’s “Much Ado About Nothing” and a list of evergreen trees, Miller features the Park’s public toilets, which may have been among the first in the country (fig. 71). His drawing of the facilities “For Gentlemen,” is among the very few visual records from this period of this new building type.[53]

Miller illustrates throughout the album the famous drinking fountains that provided pure water for the public, as well as the drains that kept rainwater off the paths (fig. 72). These details of water management go unnoticed today, but in the mid-nineteenth century they were seen as innovative modern amenities for which the Park was famous.[54]

Just as the images seem to be drawn from myriad sources, the inscribed poems and snippets of descriptive text in Miller’s “Guide” can be seen in the tradition of commonplace books in which one gathered a collection of poetic sentiments for meditation or remembering. Both the acts of writing the words in one’s own hand and carefully copying images were so that one could internalize them.[55] The title page “The Book of Lewis Miller, Sketches of original drawings, New York, 1864” in the “Guide” tells us that the pictures in Miller’s guide are re-drawings of perhaps a combination of his own sketches and prints he found to copy as aide memoirs or as exemplary artistic compositions. Miller was a witness to a burgeoning visual culture that he avidly absorbed. He is not the innocent from an imagined early moment, but a man of his times, educated in the picturesque tradition, aware of the new popular press, photography, and new places of public resort—an index not so much of folkways, but modern life.

It is paradoxical that the creation of Central Park, ostensibly as a democratic amenity for all Americans, coincided with the period of the Civil War and, thus, a moment of profound national unrest. As one New Yorker wrote about the experience of visiting the Park in 1862: “There was nothing from which one could have guessed that we are in a most critical period of a great Civil War, in the very focus and vortex of a momentous crisis and in imminent period of grave national disaster.” [56] A second paradox, often forgotten, resides in the Park’s appearance as natural landscape. It hides the engineering technology that enabled a total transformation of the site in terms of waterways, topography and plant material. It is an artificial construct and staged experience (figs. 73, 74). The picturesque park design mediated between the intense artificiality of the street grid that was advancing northwards on Manhattan Island, and what was left of the original character of the site, which was mostly swamps and rugged rock outcroppings scattered with small enclaves of African Americans and Irish immigrants.[57] The 1858 Annual Report of the Central Park Commissioners stated that: “The Park has attractions to those that visit it merely as a picture . . . the eye is gratified at the picture, that constantly changes with the movement of the observer.”[58] The Park was a work of art that, upon opening, managed to cast its spell, despite the ongoing rock blasting, excavations, and construction that continued for twenty years. The story is often told about Horace Greely, editor of the most influential newspaper of the day, the New York Tribune, who went to see that part of the Park that was finished in the early 1860s, and said to Calvert Vaux: “They have left it alone better than I thought they would.” He was not seeing the new Park as a radically new landscape aesthetic, but as natural and local.

The artifice of the Park’s naturalistic appearance was not lost on every visitor to Central Park. A writer in Appleton’s Journal of Popular Literature, Science, and Art, in 1870, commented on the landscape design and made the connection between the Jefferson’s Natural Bridge (fig. 75) and the very popular newly-built Rustic Arch (fig. 76). He wrote: “Before us is the arch of the (artificial) natural bridge, which is prettier than the Virginia wonder, and not so big.“[59] This was a new notion of the picturesque, on an urban scale. Perkins addresses the artifice of the Park, claiming the goal of the designers was to make “its features and capacities so managed as to leave the visitor under a grateful delusion. Unless of remarkably well-trained eye, the lower park appears far larger than it really is . . . and it is very easy to lose all perception of points of compass, and thus to wander at will with almost such a sense of vastness, as that which we feel in the wild woods themselves” (fig. 77).[60] Two pages of his “Guide,” in particular, exemplify Lewis Miller’s complex vision and artfulness with which he was able to combine both contemporary and romantic perspectives as if doing so were just, as he inscribed, “a walk in the Park.” (fig. 78, fig. 79). One view is of the Spur Rock or Oval Arch, labeled “Iron Bridge near 7th Avenue.” It is a drawing of one of the earliest iron bridges in America, ornamented with Gothic spandrels filled and braced by large floral wheels with interior cusping. In the foreground, a poetic figure sits on a rock ledge. From his wishful attitude, and the accompanying inscription, he seems to beg to be removed from the city that surrounds the Park. The text reads: “Draw the curtain, and let me look upon the grass and elm trees” The second view shows a path leading up a hill to the summerhouse, with boulders in the background. Miller’s poetic comment about the scene is almost ironic: “Perfect in finish as if constructed by rules of art.” Olmsted and Vaux’s Central Park was constructed by the rules of art, as was Miller’s charming album of drawings.

Whether a sketchbook or album, a traveler’s account or memoirs, Miller’s guide to Central Park, is, like its subject, a highly self-conscious, composed compilation that erases the preliminary work of its facture. It is what Ann Leigh Litwiller Betes called an “artifact of textual tourism,” a phrase used to describe works drawn from different sources—whether historical vignette, travel article, or eyewitness experience—in order to portray a place, a memory, or a sensibility.[61] Miller’s “Guide” should thus be understood, as Perkins said of Central Park, as “a graceful delusion.”

[1] Lewis Miller and Donald A. Shelley, Lewis Miller, Sketches and Chronicles: The Reflections of a Nineteenth Century Pennsylvania German Folk Artist (York, PA: Historical Society of York County, 1966), xvii. Miller’s “Guide” is separated from the major collections of Miller’s work that can be found in the collections of the Historical Society of York, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Museum, Colonial Williamsburg, and the Virginia Historical Society. Almost two thousand of Miller’s drawings have been identified. Shelley enthusiastically claimed that Lewis Miller’s oeuvre was “one of the greatest and most complete pictorial records of an era ever created by man.” Ibid., xviii.

[2] Preston Albert Barba and Eleanor Barba, Lewis Miller, Pennsylvania German Folk Artist. Allentown: Pennsylvania German Folklore Society, 1939), 10.

[3] Lewis Miller did not title his album. However, what is now bound as page 16 looks like it could have been a title page. He wrote: “Going into the Central Park, at Eight-Avenue, Book of Lewis Miller, New York, 1864, original Sketch’s of drawing’s In the Park. Guide.” For this essay, the album will be referred to a “Guide to Central Park,” or “Guide.”

[4] The catalog of the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center states, for example, that “Prior to acquisition, the book covers [of his Travel Journal for Germany] were secured between sheets of long-fibered paper, and the spine was reinforced with cloth tape. Most sheets are loose from their binding.” Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, American Folk Paintings: Paintings and Drawings Other Than Portraits from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center (Boston: Little Brown, 1988), 135.

His “Orbis Pictus” was unbound in 1979, and remains so today. Ibid., 141. The catalog also notes that the title page of Miller’s “Sketch Book of Landscape’s In the State of Virginia” is now numbered page 7, and that the non-Virginia subjects are executed on various sizes and types of paper, and include European scenes, suggesting that “John Hays, whose name appears on the book cover – grouped the collection, numbered the pages in their present order, and had them so bound.” Ibid., 144n1.

[5] “Guide to Central Park.” Object ID 66.142.1), The Henry Ford, Dearborn, Michigan.

[6] John Michael Vlach, “The Emergence of the Forgotten Folk Artists,” Folklore 96, no. 1 (1983): 115-120; and, for another important study on this subject, see also John Michael Vlach, Plain Painters: Making Sense of American Folk Art (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988). Miller is often put into the category of folk artists of “consummate importance to the student of nineteenth century rural American folkways,” Maurice A. Mook, review of Lewis Miller (1786-1882): Sketches and Chronicles, by Robert P. Turner and Donald A. Shelley, Journal of American Folklore 81, no. 321 (July-Sep., 1968): 266.

[7] Richard Gassan, “The First American Tourist Guidebooks: Authorship and the Print Culture of the 1820s,” Book History 8 (2005): 67.

[8] John David Cox, Traveling South: Travel Narratives and the Construction of American Identity (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2005), 4, 20. For a useful review essay on the topic of travel in early America see Susan C. Imbarrato, “Charting Early American Travel: Mobility, Mapping, and Identity,” Early American Literature 43, no. 2 (2008): 479-486.

[9] Frances K. Pohl, Framing America: A Social History of American Art (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2002), 465.

[10] The Montgomery Museum and Lewis Miller Regional Art Center includes works or prints by well known artists with local ties, such as Lewis Miller. Montgomery Museum and Lewis Miller Regional Art Center, New River Heritage Coalition, last accessed April 15, 2013, http://www.newriverheritage.org/members-montgomery.htm. For Pennsylvania ties, see Miller and Shelley, Lewis Miller, Sketches and Chronicles, xiii-xxii.

[11] Virgil Barker, American Painting, History and Interpretation (New York: Macmillan, 1950), 521-522.

[12] Henry L. Fisher, “Lewis Miller,” York Daily, September 29, 1882.

[13] Dell Upton, “Ethnicity, Authenticity, and Invented Traditions,” Historical Archaeology 30, no. 2 (1996): 1-7, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25616452.

[14] Donald W. Linebaugh, “Folk Art, Architecture, and Artifact: Toward a Material Understanding of the German Culture in the Upper Valley of Virginia” in The Southern Colonial Backcountry: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Frontier Communities, ed. David C. Crass, Steven D. Smith, Martha A. Zierden, and Richard D. Brooks (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988), 200-220.

[15] Mary Black and Jean Lipman, American Folk Painting (New York: C. N. Potter, 1966), 95-97. Black and Lipman characterized the work of similar artists as dedicated to three concepts: the republic, romanticism, and religion. This rings true for Miller as well in terms of the concerns of his life’s work. Ibid., 205.

[16] Manuscript from the Lewis Miller Archive, York Historical Society.

[17] Gassan, “First American Tourist Guidebooks,” 66.

[18] There are three drawing of the Natural Bridge in the collection of the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center. The Natural Bridge is a geological formation creating an arch 215-feet high with a span of 90 feet. It was purchased in 1774 by Thomas Jefferson from King George III for the American people. Jefferson touted the Natural Bridge in his Notes on the State of Virginia. With Niagara Falls, the two sites were considered the natural masterpieces of the American continent until exploration of the West overwhelmed their prominence.

[19] Gassan, “First American Guidebooks,” 54-55.

[20] Miller is paraphrasing Eliza W. Farnham’s Life in Prairie Land, from a passage describing a country seat on the Mississippi River. He uses this book several times in his “Guide,” perhaps as a source of descriptive language for the picturesque view. Eliza Wood Farnham, Life in Prairie Land (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1847), 373.

[21] Morrison H. Heckscher, Creating Central Park (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008), 70.

[22] Some of the best histories of Central Park are: Heckscher, Creating Central Park; Sara Cedar Miller, Central Park: An American Masterpiece (New York: Harry N. Abrams Publishers in association with the Central Park Conservancy, 2003); and Frederick Law Olmsted, Charles E. Beveridge, and David Schuyler, Creating Central Park, 1857-1861 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983).

[23] Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, The Park and the People: A History of Central Park (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992), 234-36.

[24] Ibid., 235.

[25] Dell Upton, “Inventing the Metropolis: Civilization and Urbanity in Antebellum New York,” in Art and The Empire City: New York, 1825-1861, ed. Catherine Hoover Voorsanger and John K. Howat (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), 45.

[26] In discussing Miller’s European drawings, Shelley states that “[h]is drawings, beginning with England . . . and Scotland, . . . enable us to follow the course of his travels and clearly place the greatest emphasis upon his wanderings around Germany.” Ibid., xvii. In the book’s catalog, Miller’s drawing of the Crystal Palace in London appears after a picture of Miller and his friends departing for Europe from New York Bay and is followed by Stirling Castle, Scotland, the Pont Neuf in Paris, and several towns in Germany. Miller and Shelley, Lewis Miller, Sketches and Chronicles, xvii, 122.

[27] Therese O’Malley, Glasshouses: The Architecture of Light and Air (New York: New York Botanical Gardens, 2005), 9.

[28] Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, American Folk Paintings: Paintings and Drawings, 144-151.

[29] Full citations: W. H. Bartlett and William Beattie, Switzerland, Illustrated in a Series of Views Taken Expressly for This Work (London: George Virtue, 1836); George Newenham Right, W. H. Bartlett, James Pattison Cockburn, Major Irton, William Leighton Leitch, and Johann Jacob Wolfensberger, The Rhine, Italy, and Greece. In a series of drawings from nature by Colonel Cockburn, Major Irton, Messrs. Bartlett, Leitch and Wolfensberger. With historical and legendary descriptions by the Rev. G. N. Wright. (London: Fisher, Son & Co.. 1840).

[30] Heckscher, Creating Central Park, 60.

[31]Visualizing Nineteenth-Century New York, on-line exhibition, Bard Graduate Center and the New York Public Library, accessed April, 11, 2013, http://resources-bgc.bard.edu/19thcNYC/maps-and-views/croton-reservoir.php.

[32] Miller, Central Park: An American Masterpiece, 123,125.

[33] T. Addison Richards, “The Central Park,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 23, no. 135, August, 1861, 298.

[34] David Tatham, Winslow Homer and the Pictorial Press (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2003), 91.

[35] For a discussion of “textual tourism” see Leigh Ann Litwiller Berte, who wrote: “The steady stream of travel writing that ran through the pages of general interest periodicals of the era documents the movement toward a destination view of geography in a new era of mobility.” Leigh Ann Litwiller Berte, “Geography by Destination: Rail Travel, Regional Fiction, and the Cultural Production of Geographical Essentialism” in American Literary Geographies: Spatial Practice and Cultural Production, 1500-1900, ed. Martin Brückner and Hsuan L. Hsu (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2007), 17

[36] An important feature of the press in 1861 was the illustrated weekly newspaper, which had been established as a news medium of significance around the middle of the 19th century. In the United States Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper emerged in 1855 and became the first successful weekly, followed by Harper’s Weekly two years later. William P. Campbell, The Civil War: A Centennial Exhibition of Eyewitness Drawings, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1961), 10-11.

[37] Elliott Bostwick Davis, “The Currency of Culture: Prints in New York City,” in Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825-1861, ed. Catherine Hoover Voorsanger and John K. Howat, exh. cat. (New Haven and New York: Yale University Press and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), 189-226.

[38] Fifty-one photographs were pasted into each copy of Perkins and Guild’s book. Hecksher, Creating Central Park, 39.

[39] Fred B. Perkins and W. H. Guild, Jr. The Central Park: Photographed, by W.H. Guild Jr., with Descriptions and a Historical Sketch by Fred B. Perkins, (New York: Clareton, 1864), 5-6.

[40] G. W. Fasel, Central Park Album, Drawn from Nature, (New York: J. Rau, 1862).

[41] The full title of the print is Mount Vernon, Drawn on the Spot and in Colors by C. H. Wells/Printed in oil colors by F. Collins.

[42] Miller and Shelley, Lewis Miller, Sketches and Chronicles, xiii.

[43] Perkins and Guild, Central Park, 9.

[44] Ibid ., 24.

[45] Ibid., 6.

[46] Perkins praises the park as the highest form of artistic achievement: “Aesthetically, - as a poet or an artist might imagine it, Mr. Inness or Mr. Bryant, for instance: -- many beautiful things, pure air, landscape views, whole chapters of spirited studies in decorative art, flower-gardens, and the collected shrubs and trees of this region and of others too; the subtler pleasures of music; the yet loftier and truer delight of seeing happy multitudes; the consciousness of belonging to a nation capable of desiring, creating, and enjoying so much beauty – all these fill the Park with the elements of beauty, with things and thoughts proper to stir into activity the best powers of artist or of poet.” Ibid., 23

[47] Lewis Miller, “Guide,” 39.

[48] Ibid., 24. “Coign: etymology: an archaic spelling of coin. 1. In the Shakespearian phrase coign of vantage: a position (properly a projecting corner) affording facility for observation or action. (The currency of the phrase is app. due to Sir Walter Scott.) coign, n.” Oxford English Dictionary Online. March 2013. Oxford University Press, accessed April 11, 2013, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/35974?rskey=pKWoRx&result=1&isAdvanced=false.

[50] Perkins and Guild, Central Park, 49.

[51] Ibid., 54.

[52] Ibid., 37.

[53] Therese O’Malley and others, Keywords in American Landscape Design, (New Haven and New York: Yale University Press, 2010), 2.

[54] Miller, Central Park: An American Masterpiece, 26.

[55] For commonplace books see “Commonplace Books,” Harvard University Open Collections Program, accessed April, 15 2013, http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/reading/commonplace.html.

[56] Hecksher, Creating Central Park, 73.

[57] Rosenzweig and Blackmar, Park and the People, 63-73.

[58] Miller, Central Park: An American Masterpiece, 11.

[59] Anonymous,“The Central Park,” Appleton’s Journal of Popular Literature, Science and Art 3, nos. 40-65, June 18, 1870, 692, as cited in Paula A. Mohr, “God in Gotham,”inAmerican Sanctuary: Understanding Sacred Spaces, ed. Louis P. Nelson (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006). 51.

[60] Perkins and Guild, Central Park, 15.

[61] Litwiller Betes, “Geography by Destination,” 172.