The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Upon visiting the city of Nancy in 1909 for the Exposition Internationale de l'Est de la France, the critic Max Durand wrote:

This summer, Nancy is a favorite destination for pilgrimage and excursion. One comes to learn, to be amused, to enjoy the natural beauty of a marvelous country, and to admire the fruits of its artistic, commercial, [and] industrial efforts.

…The [exposition's] promoters, men of goodwill and progress, motivated by the strongest patriotism, have drawn on the traditions of art and elegance which have made the former capital of [the duchy of] Lorraine a stylish and seductive city, among other things; but they have wanted also to show that the region of the East…has re-established its material prosperity and its prestige on new and durable foundations.[1]

With these words, Durand summarized well the enthusiasm for this exhibition that attracted some 2.2 million visitors between May 1 and October 31, 1909. The Exposition Internationale de l'Est de la France—often called the 1909 World's Fair—was an attempt by the leaders of this small city in eastern France to showcase the industrial and artistic progress made by their region of Lorraine over the previous forty years. The visual manifestation of this new prosperity was Art Nouveau, which had dominated the architecture and decorative art of Nancy ever since it had appeared there some two decades before, but had fallen out of favor virtually everywhere else in Europe by 1909. The staging of the Exposition Internationale de l'Est de la France marked the apex of Art Nouveau in Nancy, and, indeed, the fair represents a landmark in the history of the style, though it is often overlooked even in the literature of this specific field.[2] In Nancy, the ability of Art Nouveau to ally itself with local and regional traditions (instead of being the result of a conscious search for a new universal aesthetic) allowed it to become the cornerstone of an alternative conception of modernity during the belle époque, and to remain popular for a quarter of a century before its demise during World War I.

I argue here that the Exposition's emphasis on the cooperation between art and local industry, the political issue known as the "Alsace-Lorraine question," and the nationwide movement towards political and cultural decentralization formed the basis for the projection of Nancy's complex modern, yet regional identity, specifically as it was presented in the discourse surrounding the fair and its architecture. By 1900, Nancy had become a cosmopolitan regional center, receptive to artistic trends both from the Parisian métropole and from other countries such as Belgium and Germany, and many of these influences were readily apparent in the city's artistic scene—including, as this paper shows, the architecture and decorative art of the 1909 Exposition. Its citizens, however, were also fiercely proud of their region and its rich cultural and political heritage, which was distinct from those of the rest of France or other countries. In spite of the marked influence of these national and international forces, then, both the leaders of the fair and its critics strategically chose to downplay and discredit them in favor of what they deemed to be local sources of artistic inspiration. Their impetus for doing so was, paradoxically, to address the larger issue of the strength of the French nation in its competition for cultural superiority then being waged with the other nations of Europe.

The Development of Nancy in the Late Nineteenth Century

Nancy experienced prodigious growth over the last three decades of the nineteenth century, catapulting it to prominence and enabling the city to consider hosting an exposition as the twentieth century dawned. Before then, it had been an unlikely place for a new art movement to spring up. In 1866, the city counted barely 50,000 residents, and was overshadowed by Metz, the other principal city of the region of Lorraine, which was slightly larger and held the prestigious distinction of having hosted its own "Exposition Universelle" in 1861. One could speak of a "Metz School" of painters, interior designers, glassmakers and stained-glass artists during the thirty years preceding 1870. The city's Municipal Design School won a bronze medal at the 1867 World's Fair in Paris, whereas at the same time, Nancy's artistic scene was judged to be mediocre at best.[3]

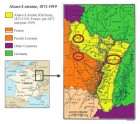

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, however, changed all that. German armies inflicted a swift and stunning series of defeats upon the French forces and captured Emperor Napoleon III, who was quickly deposed by a new government in Paris. In the Treaty of Frankfurt ending the conflict, the French ceded the region of Alsace and the northern third of Lorraine, including Metz, to the Germans (fig. 1). Nancy became the major city in the part of Lorraine retained by France, and consequently underwent a series of rapid changes and growth. The Germans gave the inhabitants of Alsace-Lorraine until October 1, 1872, to decide whether to become German citizens or to emigrate to France. By that date, some 70,000 people had flooded across the new border to settle in the département of Meurthe-et-Moselle, the area surrounding Nancy, and immigration from Alsace-Lorraine continued even afterwards.[4] Among the new arrivals in Nancy from the "lost provinces" were many prominent businessmen: the cotton magnate Emmanuel Lang brought his firm from Waldinghofen in Alsace; the printer Oscar Berger-Levrault and the barrel-maker Adolphe Frühinsholz transferred their companies from Strasbourg; and the Fould-Dupont Ironworks relocated from the city limits of Metz to the suburbs just north of Nancy (fig. 1).[5] They were joined by most of the artists of the Metz School, who over the following decades trained many of Nancy's up-and-coming artists, several of whom hailed from families that had immigrated from the lost provinces after 1871.[6] So many Alsace-Lorrainers left for France that by the late 1870s one popular saying could justifiably assert that "Metz is no longer in Metz but in Nancy."[7]

Nancy's population boomed over the next four decades, more than doubling between 1866 and 1901 and peaking at nearly 120,000 in 1911.[8] Native-born Nancy residents graciously welcomed Alsace-Lorrainers, but realized that much of the city's recent prosperity had come at the expense of their newly-arrived brethren who had been displaced from their homes.[9] Many of Nancy's citizens, including the glass artists Emile Gallé and Antonin Daum, had fought in the Franco-Prussian War and bitterly resented the terms of the Frankfurt Treaty that had divided their province.[10] They hoped that the French nation would exact revenge upon the Germans for the disaster of 1870–71 and find a way to recapture Alsace-Lorraine, but they grew ever-more dismayed with the continued refusal of the national government to take action on the issue during the 1870s and 1880s. They sensed that with every new generation, both the memory of the terrible experience of the Franco-Prussian War and the opportunities to regain the lost provinces were fading fast.[11]

This issue, often called "the Alsace-Lorraine question," was related to the debate in France in the late nineteenth century over political and cultural decentralization. Even before 1870, French citizens outside of Paris, especially in Lorraine, had come to resent the capital's domination of national affairs. This political climate was not unlike the historically complicated relationship in Spain between the national government and its provinces such as Catalonia, a situation that likewise became tense at the turn of the century.[12] For centuries, Paris had dictated fashion and taste to the rest of the country, and was often viewed by residents of the provinces as a magnet that would attract their best and brightest citizens and corrupt them with its cosmopolitan atmosphere and loose social mores. Paris's favored status was confirmed by Napoleon III, who lavished the city with the internal improvements that transformed it into the modern city we know today.[13] The resentment of this favoritism was felt by many of Nancy's citizens, who relished the fact that before 1766 Nancy had been the capital of the independent Duchy of Lorraine and had enjoyed its own artistic renaissance under the popular duke Stanislas Lesczyznski (1677–1766), the former Polish king who had commissioned the city's famous Rococo central square, the Place Stanislas (figs. 2, 3). By the turn of the twentieth century, Lorraine natives such as the writer and politician Maurice Barrès and the art critic and inspector-general of provincial museums Roger Marx had garnered national recognition with their impassioned pleas for devolved regional control of politics and culture as a means both to combat the centralized drain on local resources and to improve education.[14]

Art Nouveau and the Ecole de Nancy

These developments coalesced with the appearance of Art Nouveau in Europe during the 1890s. The support for decentralization among Lorraine artists grew increasingly stronger over the course of that decade. In the summer of 1894, the local architect Charles André organized an exposition on Lorraine decorative art at the Galéries Poirel in central Nancy, where seventy-five artists and architects from the region displayed some of their most recent work. The goal of the exposition was to "encourage the creators…who attest to the persistence of the artistic genius of Lorraine and contribute to determine the style…of our province and our time" as well as to show that "the collaboration between the artist and industrialist should be beneficial for each of them."[15] The work displayed at the 1894 exposition was not revolutionary in a formal sense, however. Louis Majorelle, who would later go on to become one of the leading exponents of Art Nouveau, exhibited pastiches of Louis XV-style furniture (fig. 4) recalling the region and nation's Rococo heritage that was popular in France in the 1890s. Nonetheless, critics immediately hailed the exhibition as a landmark event in the region's artistic development, a veritable "renaissance" that would add another chapter to Lorraine's artistic heritage, and called on all Lorrainers to resist the "prejudices, so often frivolous, of Paris."[16]

In February 1901, the artistic heritage of Nancy reached its peak when Emile Gallé (1846–1904) founded, along with several other artists and architects, a group called the "Ecole de Nancy," or, alternatively, the "Alliance Provinciale des Industries d'Art."[17] Like other regional artists' associations around Europe, such as the Darmstadt Artists' Colony in Germany and La Nova Escola Catalana in Barcelona, they hoped to foster a collaborative effort among artists in diverse fields (furniture, glassmaking, ironwork, bookbinding, leatherworking, architecture, sculpture, and painting, among others) and aimed to ensure a high quality of work among artists in the Lorraine region. Keenly aware of the popularity of Art Nouveau at the time, the members of the Ecole saw themselves as some of the most prominent advocates of the style on the continent and explicitly made it the preferred stylistic vocabulary for their work. The organization was a "school" in the sense that its members shared common goals and artistic practices, but it was not an educational institution. Some of its members, such as Gallé, the brothers Antonin (1864–1931) and Auguste Daum (1853–1909), and the furniture manufacturer and ironworker Louis Majorelle (1859–1926), were artists who were heads of large enterprises. The Ecole de Nancy also included industrialists of various occupations, such as postcard magnates, barrel manufacturers, and printers. Still others were journalists and critics who acted as the mouthpieces of the group.[18]

The members of the Ecole were deeply influenced by the political, social, and cultural developments in Nancy over the previous thirty years. In their various exhibitions in Paris, Nancy, and Strasbourg over the following decade, the group continually pushed for a regionalist cultural and political agenda, and stressed the close relationship between their art and architecture and local industry (fig. 5).[19] Through their own scientific studies of the forms of local flora and plant life (endeavors which many of them, especially Gallé, passionately pursued)[20], they developed a system of semiotic vegetal motifs and local symbols to constantly make references to the Alsace-Lorraine question in their work.[21] For many Nanciens, the work of the Ecole represented the embodiment of modernity and proved that their city was at the forefront of cutting-edge European art.[22]

The Ecole de Nancy was fiercely committed to cultural decentralization within France, a stance that sometimes created tension between it and the artistic community in Paris. Upon the showing of the Ecole's work at the Marsan Pavilion in Paris in 1903, for example, Emile Nicolas, a journalist and member of the Ecole, remarked,

It is good that Lorraine decorative art, with all its suggestions, again reminds Paris that it is one of those places that contains the deepest thought, logic, and truth…[since] in the great city…they have the haughtiness of dictating to the provinces fashions and tastes. The province is carefully pushed aside, especially when it shows its strong personality. It is only through the talent of our fellow citizens that we can claim and they can recognize our influence on the regeneration of the arts in France at the end of the nineteenth century.[23]

This haughty declaration was not well-received in the capital, where critics argued that the 1903 exposition merely showcased the luxury Art Nouveau pieces from Nancy department stores as a commercial ploy, not as the fruit of serious artistic development over the previous decade.[24] Yet, even though the Ecole's works failed to impress the critics in Paris in 1903, other exhibitions of the group's work revealed that the Nancy-Paris artistic dynamic could be quite cordial, and even friendly. When the group exhibited in Nancy in the fall of 1904 (fig. 6), Henri Marcel, the central government's new Directeur des Beaux-Arts, remarked during the opening ceremonies that the decentralizing programs of Nancy had been merely a "half-success" that the Ecole de Nancy had shrugged off over the past year. In their place, he asserted, the Ecole had adopted a new "provincial patriotism," which, "far from enfeebling French nationality… multiplies its force of influence and propaganda, [just as] the vitality of a country resides in the vigor and cohesion of groups that compose it."[25] The artists of the Ecole de Nancy readily agreed with his words, emphasizing their continued devotion to the French nation as displayed in their works and downplaying the devolved local control for political and cultural matters that they fervently craved.[26] Thus the Ecole's members frequently walked a fine line between cooperation and antagonism with their Parisian colleagues.

Planning and Designing the Exposition: Universal, Regional, or International?

Nancy's civic leaders who planned the exhibition understood that it represented, on one hand, an opportunity to showcase their region's achievements in business, industry, and culture, and that such an objective required strategically casting Nancy and Lorraine in a certain light. First proposed in 1904 by the editor of a local construction journal, Emile Jacquemin (1850–1907), the Exposition caught the attention of members of the Chamber of Commerce of Meurthe-et-Moselle, who initially planned to hold it in 1906, but conflicts with other European fairs caused the date of the exhibition to be pushed back to 1909.[27] The Exposition's proponents advocated the fair's "universal" nature, in the sense that it would offer exhibition space for all kinds of products, materials, and curiosities. Geopolitically, the exposition was conceived as having a "regional" and "cross-border" character.[28] These were, in fact, two different ideas; Jacquemin explained that the fair should demonstrate how the region had developed over the past forty years, and particularly that it should be "a decentralizing manifestation" that excluded any products that came from Paris, in order to show that Nancy could "produce and furnish it just as well, if not better than the capital."[29] Within France, the fair was intended as an example of how local control over politics, culture, and economics was ultimately beneficial to the nation, as such administration allowed the provinces to develop their own vitality and strength.

In using the "cross-border" label, the exposition's organizers recognized Nancy's geographic position on the frontier, and specifically the special relationship that the city wanted to cultivate with the nearby regions and countries of Alsace-Lorraine, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Switzerland. The exposition was intended to foster good relations with these areas, especially since the city's leaders knew that some of the industrial prowess of Lorraine rested on foreign investment, such as the Belgian Solvay Company's soda plant located just south of Nancy.[30] In particular, they hoped to strengthen the ties between French Lorraine and Alsace-Lorraine in order to remind both the central government in Paris and the Germans of their desire to see the lost provinces returned to France.

The fair's directors quickly assembled a team of architects, all of whom were renowned for their Art Nouveau work in Nancy, to design the pavilions and grounds. They included Emile André, Gaston Munier, Louis Marchal, Emile Toussaint, Louis Lanternier, Eugène Vallin, Lucien Bentz, Charles-Désiré Bourgon, Paul Charbonnier, Lucien Weissenburger, Alexandre Mienville, Léon Cayotte, and Georges Biet. The choice of these men was very strategic: as one local magazine reported, "the group…affirms its artistic sympathy for the Ecole de Nancy, [such that] none of [them] remain indifferent regarding the Ecole's work."[31] The Ecole itself announced early on that it would have its own pavilion, designed by Vallin, whose completion was highly anticipated as one of the fair's premier attractions.[32]

The exposition was held in the Parc Sainte-Marie in the rapidly-expanding southwest part of Nancy. It was laid out in three distinct sections (fig. 7). From the entry gate, located at the eastern end on the rue Jeanne d'Arc, the visitor followed a long, straight promenade past the Alsatian Village and the local Ecole des Beaux-Arts before reaching the wooded parkland that contained the Ecole de Nancy's pavilion and most of the smaller exhibition structures, which were laid out along winding paths. This part of the fair housed official services, a café, and the attractions for pure amusement, including a water chute, a children's puppet theater, and a miniature railroad that encircled the grounds (fig. 8).

Finally, the visitor entered the Blandan grounds, named for the street bounding the exposition to the west (fig. 9).[33] This area contained a plaza surrounded by a U-shaped array of the seven major exhibition pavilions—the Palais des Fêtes (Main Building) in the center,[34] flanked by the individual themed structures: the Pavilion of Mines and Metallurgy, the Electricity Pavilion, the Textiles Pavilion, the Food Pavilion, the Pavilion of Liberal Arts, and the Transportation Pavilion. At the center of the plaza was a small garden. This layout echoed the U-shaped court or lagoon around which the major structures were arranged at both the 1900 World's Fair in Paris and the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago; at each of these fairs the main (or administration) buildings were placed at the juncture of the two wings of the U (figs. 10, 11), as in Nancy in 1909.

Many of the architects of the Exposition Internationale de l'Est de la France also derived their use of ornament from past World's Fairs, décor that could hardly be described as Art Nouveau. The pavilions were wood-framed structures disguised by a covering of white stucco, with flamboyant Baroque- or Rococo-inspired ornament and décor that roughly resembled the structures at the 1900 World's Fair in Paris (fig. 12), the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago (fig. 13), and the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis (fig. 14), but on a much smaller scale. Alexander Mienville and Léon Cayotte's Palace of Liberal Arts[35] and Food Pavilion (figs. 15, 16), which sat side-by-side on the south side of the Blandan court, each recalled the design strategies used in railway stations in Paris and Nancy in the mid-nineteenth century. The three-gabled Palace of Liberal Arts, for example, which was illuminated by day by rows of skylights on its hipped roof, begs comparison with the roofs of train sheds for Parisian stations such as the Gare Saint-Lazare (fig. 17). The front of the pavilion, with its heavy modillions and molded cornice, recalls the gabled façades of the Gare de l'Est and Nancy's own main train station (figs. 18, 19)—buildings that were pivotal travel points for most visitors to the exhibition. The barrel vault of the Food Pavilion, which also relied on skylights for illumination, resembled an alternative structural form used by contemporaneous architects for train sheds and main station concourses as well as for exhibition buildings. Surprisingly, however, none of these connections to such architectural types or monuments were made in print by either the directors of the exhibition or the attendees.[36]

The Relationship Between Art and Local Industry

One connection that the Exposition's directors did hope to highlight was the link between art and industry in Lorraine, a theme that was explicitly celebrated in Louis Lanternier and Eugène Vallin's Pavilion of Mines and Metallurgy (fig. 20), the structure on the Blandan grounds that justifiably attracted the most attention. This building occupied the entire north side of the central court, and, like the other major pavilions, used a rectangular, open plan and hipped roof. Its Art Nouveau façade, however, clearly set it apart from the others. Vallin was responsible for its design, which consisted of five elongated sections of gridded windows usually seen in factories set into a framework of flat-topped arches. These arches were separated by spandrels decorated with the exaggerated imagery of chimneys rising above the pavilion's long horizontal roofline. The ends of the façade were marked by stout, multi-sided pylons that were also supposed to evoke the forms of tall chimneys at a steel mill. Vallin had originally imagined these pylons and the spandrels to hold functional torches (fig. 21), and in the final design they were equipped with modern lamps that at night glowed red like the fiery exhaust from factory smokestacks.[37] Vallin's son Auguste, meanwhile, painted several panels at the base of the façade that showed the steps in the fabrication of iron, leaving no doubt about the inspiration for the building's design. Observers marveled at the connections that the building drew with the industrial architecture of the region,[38] and indeed, the pavilion essentially inverted the strategy used elsewhere on the Blandan grounds. Instead of hiding the industrial character of the structure behind a stucco covering, here Vallin allowed the true nature of the building to pierce through the white skin and become manifest on the exterior.

The connection between art and industry was also apparent in the central bucolic park, where visitors encountered the "Maison des Magasins Réunis," the pavilion of the Nancy-centered Magasins Réunis, the only major French department store chain based outside of Paris (fig. 22). The store was headed by the Art Nouveau patron Jean-Baptiste Corbin, who had built the chain into a commercial empire of more than a dozen stores throughout Lorraine and in Paris.[39] Designed by Lucien Weissenburger, the company's house architect, the rectangular pavilion was fronted by a stairway leading up to an arched doorway flanked by two towers, each terminating in a webbed metal sculpture. This design recalled not only the twin-towered scheme for department stores such as the Magasins Réunis in downtown Nancy, but also mimicked a cathedral façade (which led to the use of the nicknames "cathedrals of consumption" and "temple of commerce" for department stores).[40] The religious connotations were extended by Weissenburger's use of an allegorical sculpture of commerce above the pavilion's main entrance, like a tympanum over the main doorway of a church. Inside were several model rooms furnished for modern living, equipped largely with items that were sold in the store's branches, including Art Nouveau furniture, vases and stained glass designed by members of the Ecole de Nancy (fig. 23). Thus the pavilion not only used Art Nouveau as a seductive means to advertise the industries of clothing and interior décor, but the use of the style in furnishings reminded visitors of the extent to which Art Nouveau permeated the everyday life of the residents of French Lorraine and remained the hallmark of the newest, most fashionable designs produced there.

Representing Alsace-Lorraine

The exposition's organizers also specifically wanted the fair to demonstrate what they saw as a special relationship between French Lorraine and the lost provinces, a theme that was particularly evident in the Pavilion of the Ecole de Nancy. To the right of the entrance inside the structure, the group placed a portrait of its founder Gallé, who had died in 1904 and had become famous for injecting his works with explicit iconographic references to the Alsace-Lorraine question. One of Gallé's most famous works, a large inlaid table known as Le Rhin ("The Rhine"), created for the 1889 World's Fair (figs. 24a and b), sat under the pavilion's central rotunda. The frieze that spans the tabletop depicts, in the center, a bearded god, representing the Rhine River, warding off an armed group of Germans, on the right, from a woman that he holds in his arms, representing Lorraine. On the left half of the frieze is an armed group of warriors, representing France. Inlaid above the scene are the words "The Rhine separates the Gauls [from] all of Germany," a reference lifted from Tacitus.[41] Between the table's legs, Gallé included the words "I cling to the heart of France,"[42] as well as a large thistle (a symbol of both Nancy and Lorraine associated with retribution). Gallé was referencing the German seizure of Alsace-Lorraine, and claiming that the natural border between Germans and Frenchmen really was the Rhine, the eastern border of Alsace. He implied that Lorraine sought retribution against those who sought to harm her, and specifically the Germans who had divided the region. Around the exterior walls of the pavilion stood individual booths containing the Art Nouveau work of the various members of the Ecole, as if to illustrate the centrality of Gallé's political and artistic philosophy as an inspiration for them.

The explicit association of the region's premier artists with the Alsace-Lorraine question was extended to Emile André's design of the Alsatian Village, a cluster of buildings near the entrance to the fair that was supposed to evoke the countryside of the region (figs. 25, 26). Inside many of the buildings were genuine Alsatian residents dressed in traditional costume performing the everyday tasks of rural Alsatians. The attempt was to recreate the Alsatian landscape and regional architecture as closely as possible, implying that French citizens were innately familiar with Alsatian traditions and customs and that Alsace was naturally a part of France, not Germany.

The Alsatian Village helped to reawaken for many French visitors a sense that the issues surrounding the lost provinces remained unfinished political business. The tribute to Alsace-Lorraine went beyond the thinly-veiled claim that the region should be returned to French control, however. As we have seen, Nancy's citizens realized that the growth and vitality of their city after 1871 was in large part due to the influx of immigrants from the lost provinces. According to one observer,

You know what has happened in Lorraine since the mutilation of 1871. Prosperity has flowed to heal the wound. We say "heal," and not "close." A great number of those from the lost provinces, wanting to remain French, brought to Meurthe-et-Moselle their home, their genius, their industriousness. A marvelous amount of work has been accomplished at the extreme frontier of the country. These are the fruits of this labor that they present us, in a sort of great basket.[43]

In some ways, therefore, Nancy's residents viewed the exposition (and particularly the Alsatian Village) as a means of thanking their brethren for their contributions to the city's newfound prosperity. It was even reported that since many of the members of the Ecole de Nancy had come from the lost provinces and "their patriotic exodus had only further imbued them with the qualities of the [French] race," their experiences thus served as the inspiration for the erection of the Alsatian Village as a means to commemorate this "fecund alliance of fraternal efforts."[44] The exhibit acknowledged that the heritage of the lost provinces was now an integral part of the construction of the city's identity, in a way that was not apparent before 1871. The recognition of this "mixed" heritage extended to the celebrations that punctuated the exhibition's run. Frequently, musical groups from Alsace-Lorraine were invited to perform at the exhibition, and one day of festivities even involved a parade of several people dressed up as characters from Lorraine history, including Jeanne d'Arc, who was popularly viewed as a protector of Lorraine and symbolized the hope for reunification of the northern part of the province with France.[45]

Decentralization and Regional Pride

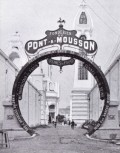

As noted above, as early as the planning stages of the fair, the discourse surrounding it was sympathetic to the longstanding movement in Lorraine towards political and cultural decentralization, aiming to demonstrate how the industrial activities of the provinces worked both in concert and in competition with the Parisian metropole. The exhibits of the iron foundries of the city of Pont-à-Mousson, just north of Nancy, illustrate the cooperative efforts of Lorraine industry with corporations in the capital. Between the Palace of Liberal Arts and the Palace of Textiles, the foundries installed a giant iron ring used for the construction of underground subway tunnels (fig. 27).[46] The company proudly adorned the ring with signs that advertised the fact that this was the model used for its fabrication of the recently-completed tunnels of the Paris Métropolitain running under the Seine.[47] Crowning the display was a small iron representation of a thistle symbolizing Lorraine, emphasizing the fact that the realization of the most modern and innovative constructions of French mass transport depended on the provincial industrial factories in Lorraine.

The importance of local enterprises to the overall industrial strength of the nation was likewise apparent in the main entrance gate to the exhibition. This skeletal steel structure designed by Paul Charbonnier (fig. 28) took the form of two tapering pylons some twenty-three meters high, flanking a horseshoe arch crowned by the coat of arms of the city of Nancy and six French flags. The entire gate was built by the Fould-Dupont steelworks in Pompey, the same company that had supplied the iron for the Eiffel Tower in 1889 (fig. 29), and despite obvious differences in overall design and scale, the Nancy structure no doubt recalled the Parisian tower from twenty years before: visitors similarly had entered the southern portion of the 1889 Fair by passing underneath Eiffel's arches. Formally, however, Charbonnier's gate invited a much closer comparison to René Binet's monumental entrance gate to the 1900 World's Fair (fig. 30), which consisted of an ornate three-legged horseshoe arch flanked by two obelisk-like pylons. In this sense the 1909 fair could be seen as a hybrid of these two previous manifestations of French Art Nouveau. The 1889 fair, held at the dawn of the style's existence, had likewise celebrated the triumph of modern industry, while the 1900 fair had heralded the return to traditional, French craftsmanship by injecting the style with a Rococo-inspired classicism with organic, naturally-inspired décor.[48] The undulating scrolls that followed the span of the arch further suggested the gilded curves of the ornament covering Emmanuel Héré and Jean Lamour's Rococo iron gates for the Place Stanislas from the 1750s (see fig. 3), thereby placing the design's roots in line with Nancy's own rich industrial and artistic heritage.

Observers, however, ignored any such connections that Charbonnier's gate exhibited with models from either Paris or previous eras. According to Louis Laffitte, the director of the 1909 Exposition, the gate symbolized "the power and boldness" of Lorraine's steel and iron industries,[49] while one Parisian observer was struck by the way that the gate was "picturesquely decorated with corrugated iron, folded rails, cartwheels, towing bars, [and] V-shaped iron pieces; in short, all the pieces which a great steelworks produces."[50] For contemporary observers, the importance of the architecture of the Exposition lay primarily with its aspects that linked it to the region's recent accomplishments, not with the capital, whose influence clearly also had contributed to Nancy's success.

Reactions to the Fair

The reaction to Charbonnier's monumental gate was typical of those to the exhibition in general. If the fair was profitable for Nancy in an economic sense, on a national level it was also highly successful in projecting an image of the city and region that confirmed the regional identity that the Exposition's organizers had set out to mold. This success was mostly due to the enthusiastic Parisian response, which emphasized both the admirable example that Nancy set for the rest of the nation to follow as well as the contributions that Nancy and Lorraine had made to the French nation.

Significantly, both the national and regional press associated the exposition's "home-grown" character with the issue of Nancy's artistic progress over the previous forty years. As one publication insisted,

For those who know how to look, see, and appreciate, [Nancy] is more than simply a banal modern city loaded with all the advantages of hospitality. It is a home of art, a perfect poem of architecture and history of which all the edifices, all the monuments, all the stones recall a period or write a page in the annals of the city.[51]

The respect Nancy's artists had shown for the city's history was one of the keys to creating a modern and vibrant artistic movement. Nancy's modernism was laudable precisely because it was not a complete break from the past, but fit into a sense of tradition. It was, according to one Parisian observer, the regional character of Nancy's artistic development that had allowed its brand of Art Nouveau to succeed where that of the capital had failed:

It is in Nancy that the "modern style,"[52] after its somewhat-too-timid manifestation at the Paris World's Fair, in 1900, seems to have found its voice…and in recalling the memories which it borrows from a visit to the galleries of the esplanade des Invalides, the amateur who travels to the real exposition at Nancy—the Palace of [Liberal Arts], the exposition of decorative arts, the Gas Pavilion, the various installations, and above all, the pavilion of the Ecole de Nancy—can measure the distance that has been established between an intense, yet too hasty effort…and the logical deduction of rational and fecund principles.

…The principle of "Lorraine art" is the same from which the "modern style" proceeded: the interpretation of nature; but from this premise, against its predecessor, it draws the rational consequences, with this practical sense, this taste, this measure, this equal aversion for that which is complicated and vulgar, which are the mother qualities of the Lorraine spirit.[53]

The careful devotion to the scientific study of nature, and the rational and practical application of the forms and designs of the natural world, as originally advocated by Gallé, had produced the admirable Lorraine brand of Art Nouveau. These qualities had resonated with Nancy's residents and allowed it to overtake Paris as the leading center of Art Nouveau in France by the end of the first decade of the century.

Even more importantly, Parisian writers described the fair as a celebration of national unity and pride. The press jubilantly noted the patriotic oration made by Louis Barthou, the French Minister of Public Works, at the inauguration, which was received by a thunderous ovation. The Revue de Tourisme declared that "Nancy can offer to the artist, the observer, and to the tourist, an altogether complete and harmonious ensemble of the evidence of the genius of the race."[54] As Jean Lefranc concluded in Le Temps, "The friends and the admirers of Lorrainers—that is to say, all Frenchmen—have no more dear desire than the perpetuation of this entente."[55]

At first glance, it may seem surprising that, in light of the longstanding uneasy relationship between Paris and the provinces, Parisian observers remained complementary and seemingly unconcerned by this cultural challenge. However, as Nancy Troy has shown, in 1909 the French remained deeply worried about their empirical predominance in cultural—and particularly artistic—production among European countries, a position that had been growing ever-more precarious over the previous thirty years.[56] The French rivalry with the German-speaking countries was especially intense, and foreigners were well-aware of the historical tendency in France towards centralization and the complicated relationship between Parisians and the provinces. As the Frankfurter Zeitung declared, "When one speaks of France, ninety-nine times out of a hundred one means to say 'Paris.'"[57] Some in Germany viewed the fair as evidence of growing decentralization, and documented the prodigious growth of Lorraine industry. They believed that because Parisians were worried about their cultural and economic dominance within France, they had purposely ignored such developments, an oversight that, the Nancy critic Pol Simon surmised, the Germans hoped would prove detrimental to the French nation.[58] It thus seems likely that, in emphasizing the issue of French decentralization, the Germans were attempting to drive a wedge between Paris and the provinces so as to thwart any such coordination of French industrial, economic, and cultural interests.

The Germans also credited the advances in Lorraine art and industry not to the French themselves, but to many of the Alsace-Lorrainers who had immigrated after 1871.[59] One reviewer from the Viennese paper Die Zeit argued that there was nothing interesting about the fair at all, as it was really merely the work of Germans who had moved to territory that had only a tenuous claim to being French.[60] Nancy critics dismissed the Austrian's assessment as the work of a "pan-Germanist" who refused to give the French credit for their own progress,[61] but it seems that the writer was influenced by other concerns. The critic Eugène Martin began a review of the fair by recalling a 1904 piece from the Heidelberg revue Korrespondenz aus Südwestdeutschland that had expressed dismay over the fact that Nancy had grown so rapidly since 1871 that by 1900 it overshadowed both Metz and Strasbourg, the two major cities in German-controlled Alsace-Lorraine, as the undisputed "artistic capital of the entire region."[62] The Germans were dismayed that France had benefited from the loss of territory in 1871 because most of the economic assets of the lost provinces had been transferred to the other side of the border. The reviewer for Die Zeit may thus have been hoping simply to downplay the entire exhibition altogether so as to assuage the German fears that the development of Alsace-Lorraine had not been as prodigious as the economic growth on the French side of the border.

Conclusion

From a wider perspective, then, the fair was not simply a means by which Nancy revealed to the wider world how Art Nouveau had developed into an emblem of regional economic, artistic, and industrial prowess. Instead, it indicated that Lorraine Art Nouveau and the industries associated with it had become a lightning rod for the ongoing cultural competition between France, Germany, and other European nations. Eventually, what some officials in France dubbed the "artistic war with Germany"[63] would be subsumed into the bloodbath of the First World War.

As with most temporary exhibitions, nearly all of the structures of the Exposition Internationale de l'Est de la France were destroyed within a year of the fair's closing.[64] Nonetheless (and contrary to popular opinion), the fair did not represent the "swan song" of Art Nouveau in Nancy, which continued to attract both elite and bourgeois enthusiasts in Lorraine until 1914, encouraging collaboration in the style between architects, artists and industrialists of the Ecole de Nancy.[65] As a permanent reminder of the region's economic and artistic vitality, the fair's director, Louis Laffitte, produced a lavishly-illustrated 900-page report, which was not published until 1912 but remains the definitive account of the exhibition.[66]

It was, however, the war that put an end to Art Nouveau in Nancy; some of its artists moved away, many of the city's decorative art firms never recovered, and a few of its major Art Nouveau landmarks were destroyed, including Corbin's Magasins Réunis. The recapture of Alsace-Lorraine in 1919 meant that Strasbourg replaced Nancy as the most important city on the eastern frontier. Gradually, Nancy was re-assimilated into Parisian-dominated circles of French art, which fell under the spell of Art Deco after 1920.[67] Even so, the attitudes shown by Nancy's citizens during the belle époque and the preservation of the dozens of surviving Art Nouveau monuments and furniture in Lorraine since then have marked the period as an integral piece of the region's historical and current identity, still being rediscovered by art historians, that is unlikely to be relinquished.

[1] Max Durand, "Nancy, II: A Travers l'Exposition," Les Annales Politiques et Littéraires, August 8, 1909, 129.

[2] See, for example, Frank Russell, ed., Art Nouveau Architecture (New York: Rizzoli, 1979); Paul Greenhalgh, ed., Art Nouveau 1890–1914 (London: V&A Publications, 2000); Béatrice Foulon, ed., 1900 (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2000); and Gabriele Fahr-Becker, Art Nouveau, trans. Paul Aston, Ruth Chitty, and Karen Williams (Cologne: Könemann, 2004).

[3] Pierre Barral, Françoise-Thérèse Charpentier, and Jean-Claude Bonnefant, "La Capitale de la Lorraine Mutilée (1870–1918)," in Histoire de Nancy, dir. René Taveneaux (Toulouse: Privat, 1979), 393. On Metz's predominance, see Christiane Pignon-Feller, "Les Fêtes de l'Art et de l'Industrie: Lieux d'Echanges entre Metz et Nancy," in Metz/Nancy-Nancy/Metz: Une histoire de frontière, 1861–1909, ed. Monique Sary, Isabelle Bardiès, and Christian Debize (Metz: Musées de la Cour d'Or/Editions Serpenoise, 1999), 60–64.

[4] Hélène Sicard-Lenattier, Les Alsaciens-Lorrains à Nancy: Une Ardente Histoire 1870–1914 (Haroué, France: Gérard Louis, 2002), 56.

[5] On the émigrés from Alsace-Lorraine to France, see François G. Dreyfus, "Le malaise politique," in L'Alsace de 1900 à nos jours, ed. Philippe Dollinger (Toulouse: Privat, 1979), 99–101; Francis Roussel, Nancy Architecture 1900, vol. 1, De la rue de l'Abbé Gridel à la rue Félix Faure (Metz: Serpenoise, 1992), 5–6, 16; Jean-Pierre Klein and Bernard Rolling, Histoire d'un imprimeur:Berger-Levrault 1676–1976 (Nancy: Berger-Levrault, 1976), 98–104; David H. Barry, "The Effect of the Annexation of Alsace-Lorraine on the Development of Nancy" (PhD diss., University of London, 1975), 321–37 and 345–49; Sicard-Lenattier, Les Alsaciens-Lorrains à Nancy, 116–49; and Barral, Charpentier, and Bonnefant, "Capitale de la Lorraine," 406–10.

[6] See Barry, "Effect of the Annexation," 398–432; and Sicard-Lenattier, Les Alsaciens-Lorrains à Nancy, 194–204.

[7] François Roth, "La Lorraine Divisée," Taveneaux, Histoire de Lorraine, 392.

[8] Barral, Charpentier, and Bonnefant, "Capitale de la Lorraine," 393.

[9] Sicard-Lennatier, Les Alsaciens-Lorrains à Nancy, 10, 216–20.

[10] Gallé and Daum both wrote about their wartime experiences. See Alain Dusart and François Moulin, Art Nouveau: l'épopée Lorraine (Strasbourg: La Nuée Bleue/Editions de l'Est, 1998), 13–15; and Philippe Garner, Emile Gallé, rev. and enl. ed. (New York: Rizzoli, 1990), 19–20, 25–26.

[11] François Robichon, "Representing the 1870–1871 War, or the Impossible Revanche," trans. Olga Grlic, in Nationalism and French Visual Culture, 1870–1914,ed.June Hargrove and Neil McWilliam (Washington, DC/New Haven: National Gallery of Art/Yale University Press, 2005): 82–99; and Robert Allen Jay, "Art and Nationalism in France, 1870–1914" (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1979), 211–12.

[12] See Judith Rohrer, "Artistic Regionalism and Architectural Politics in Barcelona, c. 1880-c. 1906" (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1984), for more on the turn-of-the century relationship between Barcelona/Catalonia and the Spanish government.

[13] On Napoleon III's improvements, see David Pinckney, Napoleon III and the Rebuilding of Paris (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1958). On French regionalism and the Paris/province dynamic, refer to Alain Corbin, "Paris-Province," in Realms of Memory: The Construction of the French Past, dir. Pierre Nora, vol. 1, Conflicts and Divisions, dir. Pierre Nora, ed. Lawrence Kritzman, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996): 427–64; also Jean-Claude Vigato, L'Architecture Régionaliste: France 1890–1950 (Paris: Institut Français d'Architecture/Editions Norma, 1994), esp. 19–73.

[14] Robert Gildea, The Past In French History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), 177–82. Also Richard Thomson, "Regionalism versus Nationalism in French Visual Culture, 1889–1900: The Cases of Nancy and Toulouse," in Hargrove and McWilliam, Nationalism and French Visual Culture, 210–11.

[15] "Programme de l'Exposition," in Exposition d'art decorative et industriel lorrain, juin-juillet 1894: catalogue (Nancy: Berger-Levrault, 1894), n.p.

[16] X., "Exposition des Arts Décoratifs: Préliminaires," in Le Progrès de l'Est, July 4, 1894, 2; and L. F., "Exposition des Arts Décoratifs," in L'Est Républicain, July 7, 1894, 2; Emile Badel, Les Arts Décoratifs en Lorraine: Notice Sur l'Exposition de la Salle Poirel, Juillet 1894 (Nancy: Imprimerie A. Voirin et L. Kreis, 1894), 3–10; Emile Badel, "Exposition des Arts décoratifs—Visite d'ami. Les Oeuvres nouvelles," in L'Immeuble et la Construction dans l'Est, July 29, 1894, 99–101.

[17] In English, the "School of Nancy," and "Provincial Alliance of Industries of Art."

[18] Many of them were listed in the original copy of the Ecole de Nancy: Statuts (Nancy: Barbier and Paulin, 1901).

[19] The Ecole de Nancy held expositions at the Pavillon de Marsan in Paris in March 1903; at the Galéries Poirel in Nancy in October-November 1904, and at the Palais de Rohan of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Strasbourg in 1908. On these, see Emile Gallé, "Programme de l'Ecole de Nancy," in Exposition de l'Alliance Provinciale de Industries d'Art/Ecole de Nancy, Mars 1903 – Catalogue Officiel Illustré, 3–5; Emile Gallé, L'Exposition de l'Ecole de Nancy à Paris (Paris: A. Guerinet, 1903), n.p.; Emile Jacquemin, "Les Arts décoratifs lorrains – Salle Poirel à Nancy," L'Immeuble et la Construction dans l'Est, October 30, 1904, 211. Also see "L'exposition d'art décoratif," in L'Impartial de l'Est, October 26, 1904, 2; and Alexandre Tourscher, "Strasbourg-Nancy: Autour de l'exposition de l'école de Nancy en 1908," in Strasbourg 1900: Naissance d'une capitale, dir. Rodolphe Rapetti (Paris/Strasbourg: Editions d'art Somogy/Musées de Strasbourg, 2000), 142.

[20] For more on this, see François Hirtz and Pierre Valck, "Nancy, Capitale de l'horticulture et de la botanique," in Dossier de l'Art, April 1999, 62–69; Philippe Thiébaut, Emile Gallé: Le magicien du verre (Paris: Gallimard, 2004), 72–74; François Le Tacon, "Emile Gallé, la botanique et les idées évolutionnistes à Nancy à la fin de XIXe siècle," in "Actes du colloque public en hommage à Emile Gallé,"special issue, Annales de l'Est 55 (2005): 73–94; Le Tacon, Emile Gallé, Maître de l'Art Nouveau (Strasbourg: La Nuée Bleue/Editions de l'Est, 2004); and Françoise-Thérèse Charpentier and Philippe Thiébaut, Gallé (Paris: RMN, 1985).

[21] Peter Clericuzio, "Nancy as a Center of Art Nouveau Architecture, 1895–1914" (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, forthcoming 2011), esp. chap. 2, "The Ecole de Nancy and Nancy's Artistic Scene, 1889–1914." Emile Gallé himself kept extensive gardens around his estate, "La Garenne," in Nancy, and was deeply involved in the scientific study of horticulture, eventually becoming a prominent member of the Société Centrale d'Horticulture de Nancyin the 1880s. See Hirtz and Valck, "Nancy, Capitale de l'horticulture," 62–69; Thiébaut, Emile Gallé, 72–74; Le Tacon, "Emile Gallé, la botanique et les idées évolutionnistes," 73–94; Le Tacon, Emile Gallé, Maître de l'Art Nouveau; and Charpentier and Thiébaut, Gallé.

[22] Hippolyte Langlois, "Nos Grandes Villes: Nancy," L'Est Républicain, October 12, 1908, 2; G. Philbert, "Histoire de l'Art," L'Impartial de l'Est March 23, 1909, 1; and "L'Exposition de la Cité moderne expliquée par le milieu," Exposition Cité Moderne (Nancy: Chambre de Commerce de Nancy/Société Industrielle de l'Est, 1913), 237–43.

[23] Emile Nicolas, "Les artistes décorateurs lorrains à Paris," L'Etoile de l'Est, February 28, 1903, 2.

[24] "A quoi sert le pavillon de Marsan?" in Occident, issue unknown, quoted in Emile Nicolas, "L'Exposition du Pavillon de Marsan," La Lorraine Artiste, June 1, 1903, 174.

[25] His remarks were printed in "Discours de M. Marcel, Directeur des Beaux-Arts," L'Impartial de l'Est, October 31, 1904, 2.

[26] Emile Nicolas, "L'Exposition d'Art Décoratif de Nancy," Le Pays Lorrain, November 25, 1904, 349.

[27] E. Collin, Exposition Internationale de l'Est de la France, Nancy, 1909: Guide Officiel (Nancy: L. Bertrand, 1909), 13. Also see Louis Laffitte, Rapport Général sur l'Exposition Internationale de l'Est de la France – Nancy 1909 (Paris/Nancy: Berger-Levrault, 1912), xi–xvii; and Béatrice Damamme-Gilbert, "The 1909 Nancy International Exhibition: Showcase for a Vibrant Region and Swansong of the Ecole de Nancy," Art on the Line 1, no. 5 (2007): 3.

[28] Emile Jacquemin, "Les Caracteristiques de l'Exposition de Nancy," L'Exposition de Nancy en 1908, July 1906, 68.

[29] Also see Charles Georgin, "Lettre d'un Parisien de Lorraine," L'Exposition de Nancy en 1908, February 1906, 35–36.

[30] Members of the Ecole de Nancy cultivated especially close ties to the Solvay company. Ernest Solvay, whose town house in Brussels was designed by Victor Horta, established a major soda-producing factory at Dombasle-sur-Meurthe, near Nancy, and became good friends with Gallé, Majorelle, and other local artists. In 1903, he commissioned Gallé to create two vases celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of the establishment of his plant in Lorraine. The example now conserved at the Musée de l'Ecole de Nancy depicts the Solvay factories, with droplets at the rim and crystalline forms at the base that evoke the process of soda production and the raw material. See François Roth, "Art et Industrie," in Françoise-Thérèse Charpentier and others, Art Nouveau: L'Ecole de Nancy (Metz: Denoël/Serpenoise, 1987), 31. Also see Gallé to Roger Marx, September 30 and October 1, 1903, both transcribed in Françoise-Thérèse Charpentier, Emile Gallé—Roger Marx: Correspondance 1882–1904 (Thèse de doctorat, Paris, 1970), 470–71, 474–76.

The Nancy connections to Solvay also include Edouard Hannon (1853–1931), a Belgian who was the supervisor at Solvay's Dombasle plant from 1877–83. A photography enthusiast, Hannon commissioned Gallé and Majorelle for the lighting and furniture of his Art Nouveau villa in Brussels, designed by Jules Brunfaut in 1903. The house is now a museum dedicated to photography and Hannon's connections with Art Nouveau. On this, see Marcel M. Celis, L'Hôtel Hannon (Brussels: Editions Contretype, 2003).

[31] Lucien Humbert, "Chez les Architectes," L'Exposition de Nancy en 1909, July 1907, 167.

[32] See "L'Ecole de Nancy à l'Exposition," L'Immeuble et la Construction dans l'Est, March 1, 1908, 348; "Exposition de Nancy 1909: Les Travaux de l'Exposition de Nancy," Revue Industrielle de l'Est, September 20, 1908, 792–93; "Nos décorateurs," L'Etoile de l'Est, May 17, 1909, 2; and "L'Ecole de Nancy," L'Eclair de l'Est, March 10, 1908, 2.

[33] Called the rue du Sergent-Blandan.

[34] Known in the original as the "Palais des Fêtes" (literally, "Palace of Festivals"), though obviously this term is somewhat awkward in English. The Main Building was the site of all the major celebrations and conventions held during the fair.

[35] Some of the pavilions were referred to as "pavilions" and some as "palaces," in both the official and unofficial literature surrounding the fair. I refer to the fair's buildings using the language of the period sources.

[36] I have found no primary sources that link the Nancy structures with the design of railway stations or specific previous exhibition buildings.

[37] Though modern observers have described these pylons as "blast furnaces," observers of the time connected them with factory chimneys. See Eugène Martin, "Comment l'Exposition de Nancy manifeste la vitalité industrielle et artistique de la Lorraine," La Croix, June 8, 1909, 3; cf. Frédéric Descouturelle, "De l'Art à l'Exposition," in Frédéric Descouturelle and others, Nancy 1909: Centenaire de l'Exposition internationale de l'Est de la France (Nancy: Editions Place Stanislas, 2009), 145–47; and Christian Debize, Emile Gallé and the "Ecole de Nancy," trans. Ruth Atkin-Etienne (Metz: Serpenoise, 1999), 45.

[38] Martin, "Comment l'Exposition de Nancy," June 8, 1909, 3.

[39] By 1910, Corbin had stores in Toul, Pont-à Mousson, Charmes, Epinal, Charleville, Longwy, Lunéville, Troyes, Vaucouleurs, Joeuf, Neufchâteau, Lens, Alençon, St-Mihiel, and Paris, where he also operated the Grand Bazar de la Rue de Rennes. See Catherine Coley, "Les Magasins Réunis: From the Provinces to Paris, from Art Nouveau to Art Deco," in Cathedrals of Consumption: The European Department Store 1850–1939, ed. Serge Jaumain and Geoffrey Crossick (Aldershot/Brookfield, VT: Ashgate, 1998), 237–39; Maisons des Magasins Réunis: Magasins de Vente, advertising flyer, c. 1907 (Archives of the Pharmacie Flesch, Commercy [France]); and the Liste des Principaux Travaux Executés Sous la Direction de Monsieur Lucien Weissenburger, Architecte Diplomé par le Gouvernment à Nancy (de 1888 à 1915), 32 pp. (Inventaire Général de la Lorraine, Dossier Weissenburger, Nancy).

[40] For a history of the development of the department store and its associations with religious architecture, see Meredith Clausen, "The Department Store—Development of the Type," Journal of Architectural Education 39, no. 1 (Fall 1985): 20–29; also consult Serge Jaumain and Geoffrey Crossick, "The World of the Department Store: Distribution, Culture and Social Change," in Jaumain and Crossick Cathedrals of Consumption, 1–45.

[41] Tacitus, Germania, part 1, opens, "The whole of Germany is thus bounded; separated from Gaul, from Rhoetia and Pannonia, by the rivers Rhine and Danube." Translation by Thomas Gordon; online text available at http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/tacitus-germanygord.html (accessed December 19, 2007).

[42] The original inscriptions are in French: on top, from Tacitus, "Le Rhin separe des Gauls tout de Germanie," and, on long stretchers between the table's legs, "Je tiens au coeur de France."

[43] Emile Hinzelin, "La Belle Exposition de la Bonne Lorraine," Le Petit Journal, June 7, 1909, 1.

[44] See Martin, "Comment L'Exposition de Nancy manifeste la vitalité industrielle et artistique de la Lorraine," La Croix, August 3, 1909, 3.

[45] Hélène Sicard-Lenattier, "L'Exposition en Fête," in Descouturelle and others, Nancy 1909, 129–32.

[46] Another of these rings was installed just inside the entrance to Vallin and Lanternier's Pavilion of Mines and Metallurgy. See Hélène Sicard-Lenattier, "Une Éclatante Démonstration du Savoir-Faire Lorrain," in Descouturelle and others, Nancy 1909, 44–45.

[47] Ibid. For more on the planning, design, and construction of the first several lines of the Paris Métro, see Malcolm Clendenin, "Hector Guimard, Political Movements, and the Paris Métro: Natural Sympathies, Governing Harmony, and Social Change" (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2008).

[48] Deborah Silverman, Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siècle France: Politics, Psychology, and Style (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), esp. 1–4, 297–98.

[49] Laffitte, Rapport general, 3.

[50] Martin, "Comment L'Exposition de Nancy," August 3, 1909, 3. Also see Maurice Leudet, "L'Exposition de Nancy," Le Figaro, June 21, 1909, 3, for similar observations.

[51] Maurice Leudet, "Les Journaux Parisiens et l'Exposition," Journal de l'Exposition de Nancy: Organe officiel de l'administration 26 (June 29 and 30, 1909): 3. This excerpt was taken from an article in the Revue du Tourisme.

[52] "Modern-style" was another name commonly given at the time to Art Nouveau.

[53] Martin, "Comment L'Exposition de Nancy," August 3, 1909, 3.

[54] Leudet, "Les Journaux Parisiens et l'Exposition," 3.

[55] Jean Lefranc, "Le progrès en Meurthe-et-Moselle," Le Temps, June 30, 1909, 2. Also see Leudet, "Les Journaux Parisiens et l'Exposition," 3.

[56] Nancy Troy, "Le Corbusier, Nationalism, and the Decorative Arts in France, 1900–1918," in Nationalism and the Visual Arts, ed. Richard A. Etlin (Washington, DC/Hanover, NH: National Gallery of Art/University Press of New England, 1991), 64–88. Also see her monograph Modernism and the Decorative Arts in France: Art Nouveau to Le Corbusier (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991).

[57] Lenore Ripee-Kühn, "Nancy, Aus Anlass der Internationalen Ausstellung," Frankfurter Zeitung, April 30, 1909, page unknown; quoted in Pol Simon, "L'Exposition de Nancy et l'Opinion," Laffitte, Rapport general, 836.

[58] "Ein neues industrielles Zentrum," Dresdener Volkszeitung, September 4, 1909, 1, quoted in Simon, "L'Exposition de Nancy et l'Opinion," 837–38.

[59] Two installments of "Ein neues industrielles Zentrum," Dresdener Volkszeitung September 4 and 9, 1909, n.p., quoted in Simon, "L'Exposition de Nancy et l'Opinion," 838–40.

[60] Article in Die Zeit, August 11, 1909, quoted in Simon, "L'Exposition de Nancy et l'Opinion," 841–44.

[61] Simon, "L'Exposition de Nancy et l'Opinion," 841.

[62] Martin, "Comment L'Exposition de Nancy," August 3, 1909, 3.

[63] Marius Vachon, an inspector of artistic education for the French government, was a fervent advocate for the improvement of national instruction in the decorative arts. During World War I he published a book, La guerre artistique avec Allemagne: L'organisation de la victoire (Paris: Payot, 1916), that likened the work of French artists to that of soldiers on the battlefield.

[64] With the notable exception of the Zutzendorf house, the main building of the Alsatian Village, which remains open to the public even today in the Parc Sainte-Marie.

[65] See Clericuzio, "Nancy as a Center of Art Nouveau Architecture, 1895–1914," esp. chap. 2. This phrase has been used by Dusart and Moulin, Art Nouveau: l'épopée lorraine, 121; also Béatrice Damamme-Gilbert, "The 1909 Nancy International Exhibition," 11; and Anne-Laure Dusoir, "L'Ecole de Nancy à l'Exposition Internationale de l'Est de la France," (Paper presented at the conference Expositions internationales et universelles - Laboratoire Historique 1, Bruxelles-Brussel, Brussels, October 22, 2005).

[66] This is Laffitte's Rapport Général. See note 27 above for the full citation.

[67] For more on this, see Catherine Coley, "L'effort moderne à Nancy dans les années vingt: Chronique du comité Nancy-Paris," Le Pays Lorrain 67, no. 1 (January-March 1986): 5–20.