The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

1914–1918, Le Patrimoine s’en va-t-en guerre

March 11–July 4, 2016

Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine,

Palais de Chaillot, Paris

Catalogue:

1914–1918, Le Patrimoine s’en va-t-en guerre.

Edited by Jean-Marc Hofman with essays by Corinne Bélier, Annette Becker, Claire Maingon, Cécilie Champy-Vinas, Jean-Marc Hofman, Sylvie Leray-Burimi, and Judith Kagan.

Paris: Norma Editions, 2016.

196 pp.; 55 illustrations; list of objects; bibliography; index.

15€

ISBN: 978-2-9155-4280-6

Hidden in the rear galleries of the cavernous spaces of the Palais de Chaillot was one of the most significant and timely of recent exhibitions in Paris. Dedicated to the exploration of the ways in which objects and locations in Belgium and France were destroyed by the Germans during World War I, the exhibition and its concise catalogue provided ample evidence of how art objects, architectural monuments, and educational institutions such as libraries were systematically destroyed and pillaged; destruction that the Germans eventually denied as their responsibility. Given the recent ruin of monuments by ISIS in both Syria and Iraq, this exhibition sounded a very important note of alarm for the western world that is timely and evocative of what has occurred in the past (fig. 1). Without a firm knowledge of historical events such as those surrounding World War I, this type of devastation could easily be repeated if an outcry is not raised by concerned scholars, collectors, educators, and government officials.

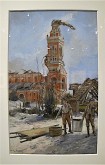

Following the introductory panel, which presented the issues addressed by the exhibition, the show was organized into three very succinct, careful, and well-developed sections. The first section was dedicated to establishing the ways in which art objects, locations, buildings, and images created by artists were used to create a “Guerre des images” (war of images). Starting with the destruction of the ancient library in Louvain, graphically revealed through documentary photographs that showed the original library building (found in a post card of the time) in contrast with its ruined state, the exhibition then moved on to ways in which artists, often men who served as war reporters at the front, created images that were reproduced in the press (fig. 2). These included works by Georges Scott for the magazine L’Illustration of the devastation of the city of Ypres after being bombarded in 1914 and 1915, or one by François Flameng, a work now housed in the Musée de l’Armée, of the destruction of the basilica of Albert in the Somme region (figs. 3, 4). When these works were shown alongside the more propagandistic prints either advocating German KULTUR or fiercely castigating what had happened, the atmosphere of a visual battle between opposing sides was apparent (figs. 5, 6). In the midst of this section, where photographs were included to reinforce the atmosphere of destruction, were documents produced by the Germans, either as books advocating their position or papers signed by some of the leading art intellectuals of the day, arguing that the destruction of artistic monuments was not the responsibility of Germany (fig. 7). Included in this list of deniers were figures such as architect and designer Peter Behrens and Justus Brinckmann, the long standing Director of the Kunst und Gewerbe Museum in Hamburg, among many others (fig. 8). Although what was uppermost in the exhibition was the way in which art was enlisted on both sides, the destruction of great monuments from the past remains a lingering, indelible image throughout this small exhibition.

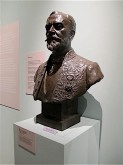

The second section of the exhibition centered on a very significant exhibition held in the Trocadéro in Paris in 1915. As the first exhibition that emphasized Germany’s vandalism, this show under the direction of Camille Enlart launched a fierce propaganda campaign against the invaders (figs. 9, 10). Bringing together images of monuments that had been destroyed, Enlart created a startling contrast with the sculptural casts from French art history—from all periods—that were also shown in the exhibition. Among the images that revealed the brutal destruction was the Smiling Angel from Reims, a sculpture that had been destroyed by the German bombardment of the cathedral and the city (fig. 11). Almost immediately the fragments from the past were seen as relics that had to be preserved even if the original had been devastated. This section became one of the most moving in the exhibition as it demonstrated that those who cared about these French monuments persevered in mounting a public exhibition to get their message out to the world.

The third section of the show emphasized The Mutilated Works of Art exhibition held in 1916 at the Petit Palais, which increased the frenzy surrounding the destruction of France’s artistic “patrimoine” (patrimony). Paul Ginisty, the organizer of the 1916 exhibition, conceived this show to inflame French anger against Germany while presenting considerable evidence of the mutilation before neutral countries who had not entered the war (fig. 12). Shown in photographs, the fragmented works, such as that of Saint Tarcisius by the nineteenth century sculptor Alexandre Falguière, became symbols of a patriotic fervor that continued to fuel the war effort. Aided by efforts in the press, the exhibition became a sort of artistic pilgrimage across France that starkly demonstrated what was happening to French culture (fig. 13). The effectiveness of the show was palpable. Similarly, the ways in which these sections of the exhibition created a tableau of desecration and destruction were used as a warning that the same thing is happening in contemporary society.

The excellent catalogue and short guide provide stimulating essays that enlarge upon a number of the themes effectively developed in the exhibition at the Palais de Chaillot. Examining the heroes of the moment, those who stood up for what was right, introduces the reader to many individuals whose roles in history have been obliterated by the passage of time. As a model of consistency, the catalogue contributes ample evidence that once the memory of this current exhibition fades away, the record of the various issues posed and discussed so insightfully will remain an educational tool for future generations. Although few visitors to Paris will take the time to see this exhibition, and even those visiting the Cité de l’Architecture might not notice the show, those that do get to see it will find it both rewarding and a model for other exhibitions to follow, especially shows motivated by history and a passion to remember.

Gabriel P. Weisberg and Yvonne M. L. Weisberg

Art History Department

University of Minnesota

vooni1942[at]aol.com