The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Constantin Meunier (1831–1905) Retrospective

Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium (Fin-de-Siècle Museum), Brussels

September 20, 2014–January 11, 2015

Catalogue:

Constantin Meunier: 1831–1905.

Francisca Vandepitte, with contributions by Michel Draguet, Dominique Marechal, Paul Aron, Denis Laoureux, Sura Levine, Peter Carpreau, Jean-Philippe Huys and Micheline Jérome-Schotsmans.

Tielt: Lannoo, 2014.

320 pp.; 209 color illus.; concise biography; selective bibliography.

Dutch and French editions

€ 39 (hardcover)

ISBN 9789401421997

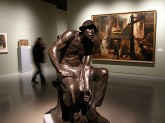

Constantin Meunier (1831–1905), one of Belgium’s most celebrated nineteenth-century artists, was the subject of a grand retrospective organized from September 2014 to January 2015 in Brussels’ Fin-de-Siècle Museum (a subdivision of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium and a welcome recent addition to the country’s cultural landscape). It is relatively well known that it was not until late in his career that Meunier came to the subject matter and medium that were to signal his international breakthrough: namely, the contemporary worker eternalized in sculpture, molded with a remarkable constraint that strips the figure of all anecdote and sentiment, and at the same time instills it with the dignity worthy of an ancient athlete.[1] Meunier was, in fact, nearing the age of fifty when he was first introduced to the industrial sites of Wallonia—Belgium’s southern region—and when, not long after, he took up sculpting after an almost three-decade-long break in favor of painting (28).

Before long, Meunier was translating his vision of modern labor in a near inexhaustible series of statues, statuettes, and reliefs, which paid homage to the anonymous men (and, on occasion, women) who slaved away in his nation’s mines, factories, and foundries. These works catapulted the middle-aged artist to the front of the contemporary art scene.[2] Indeed, by the end of the century, his international reputation was firmly established. Crowning this evolution was a retrospective of his work in 1896 in Paris, in Siegfried Bing’s famed Maison de L’Art Nouveau, which was followed by a host of exhibitions, distinctions, and commissions.[3]

So goes the familiar story, but thankfully, curator Francisca Vandepitte was not content treading well-worn paths. She took the organization of the retrospective—the first since the commemorative show in Leuven in 1909—as an opportunity to dig just a bit deeper.[4] The exhibition not only paid attention to Meunier’s iconic sculptures of heroic laborers, but also intentionally set out to highlight the paintings, drawings, and sketches, which constitute such an overlooked, yet integral part of the artist’s oeuvre; both those that Meunier made simultaneously with his sculptures at the height of his career, as well as those of a more traditional nature—religious scenes, genre paintings and history pieces—that preceded this later, so-called “industrial” period. Such a task is harder than it might seem at first glance, for there is of course a reason that the later work dominates Meunier’s artistic legacy; it is bolder and the quality is more even. Nevertheless, Vandepitte succeeded nicely in striking a balance. The result was an exhibition that managed to paint a more nuanced, well-rounded picture of an artist whose image in art historical literature is often one-sided.

The exhibition led the visitor through a selection of some one hundred and fifty artworks, which for the most part were taken from public and private collections within Belgium, and which were produced, with few exceptions, by Meunier himself. The permanent collection of the Fin-de-Siècle Museum, meanwhile, was meant to provide the broader art historical context, as was the lavishly illustrated exhibition catalogue, which bundles eight essays that explore various aspects of the artist’s life and work. The artworks were tastefully presented against walls predominantly colored in muted hues of olive green and yellow ochre, and were divided up in a total of thirteen thematic sections, each introduced by a short, one paragraph notice printed in French, Dutch, and English. Even though Meunier’s career lends itself particularly well to a clear chronological overview, the sections were only roughly arranged in chronological fashion, beginning with Meunier’s academic training and ending with the conception of the Monument to Labor that dominated the final years of his life. The through line was at times hard to distinguish, especially since the sections were unnumbered, which presumably was to allow the public to wander freely through the exhibition, but invariably led to confusion for visitors as to the extent of the exhibition and as to the most logical sequence to follow. More puzzling still is that, while each work was accompanied by a plaque that detailed the title, date, and collection of origin in three languages, the medium was never listed, a baffling choice for an exhibition that, after all, not only groups, but also essentially revolves around artworks made in a rich variety of materials, so as to demonstrate Meunier’s versatility.

Seeds are Sown, ca. 1850–1880

Let us, for clarity’s sake, distinguish between sections that relate to the period before and those that relate to the period after the decisive shift in Meunier’s oeuvre, when the artist turned both to the figure of the modern laborer and to the discipline of sculpture, a logical distinction which is also used to organize the catalogue’s introductory survey of Meunier’s artistic career (21–35). The exhibition opened with the section “Academy,” which was devoted to the schooling Meunier enjoyed at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels as a teenager; hence the reason why it was somewhat unfortunate to have the section be preceded by the portrait bust made of the elderly artist by Victor Rousseau (1865–1954), instead of opting for an image of Meunier as a young man, a soon-to-be avant-gardist, eager to craft his own artistic path. Of special significance here was the academic study of a muscular man—nude but for a piece of cloth that covers the groin—turning his torso slightly and looking off into the distance. Meunier would assimilate the prominence attributed to the male nude in traditional academic training, and would transform the classic nude into the sculpted icons of modern industry for which he is known today. The time spent at the Academy would mark Meunier’s career in a more momentous way as well, for although he had trained for years to be a sculptor, it seems that the exhaustive regimen merely served to fill the artist with a weariness of the medium.[5] At the middle of the century, sculpture was much more conservative than painting, tied as it was to conservative patrons and costly materials. When Gustave Courbet’s painting Stonebreakers was presented in Brussels in 1851, it made a profound impression on the then 23-year-old Meunier. Great things were afoot in painting, he sensed, while sculpture seemed to lag hopelessly behind (22). Before long, Meunier abandoned sculpture in favor of painting and drawing, and for over a quarter of a century did not look back.

In the handful of sections that followed, it quickly became apparent that even in his twenties, Meunier showed greatest promise when directing his attention to the common man’s struggle with existence. In his catalogue essay, Dominique Marechal attributes Meunier’s deep seated melancholia to the harsh conditions of his childhood, which was profoundly affected by his father’s unexpected passing (53).

Religion was the common thread linking the works grouped in the sections “Devotion” and “Ora et labora.” Genre scenes like The Holy Water Stoup (1854) and Young Girls in the Church (ca. 1854) are almost endearingly clumsy; the figures are rather stiff and lifeless, and the tone is unconvincingly sweet. Just a few years later, however, Meunier’s periodic immersions in the life of quietude and sobriety at the abbey of Westmalle appear to have encouraged a major artistic leap forward. In The Funeral of a Trappist (1860), Meunier represented a funeral procession at the abbey with an arresting austerity (fig. 1). While dawn breaks at the horizon, a crowd of hushed figures pours out of the church, the coffin in tow. The bold depiction of the monks’ habits especially stands out; and it is hard to shake the impression that Meunier observed the Trappists not merely with a painter’s, but also with a sculptor’s gaze, thinking in terms of volume and solidity (59–60). Of a more romantic sensibility is Monks Plowing (1863), hung on the opposite wall (fig. 2). In the vein of Jean-François Millet (1814–1875), the painting depicts two monks in a deserted field in the early morning, one crouching to adjust the plow, the other standing still, his gaze upturned. It was created together with Meunier’s colleague, the Belgian artist Alfred Verwee (1838–1895), who, although visitors remained uninformed of the terms of the collaboration, would presumably have been responsible for the two oxen, as he was a noted animal painter.

In 1868, Meunier and Verwee were founding members of the Société Libre des Beaux-Arts, an avant-garde exhibition society devoted to disseminating realism in Belgium. In fact, Verwee and Meunier are shown seated next to each other on the society’s group portrait made by Edmond Lambrichs (1830–1887), which sadly was absent from the exhibition, though it is on view in the permanent wing of the museum. Even if visitors were supposed to find their own way there, however, the painting’s plaque does not identify the sitters, nor does the caption that goes with the image in the exhibition catalogue—an unfortunate oversight.

Also portrayed in the group painting is Charles De Groux (1825–1870), another Belgian realist painter, whose masterpiece Grace (1861) is part of the collection of the Fin-de-Siècle Museum. De Groux and Meunier met during the latter’s studies; and De Groux—seven years Meunier’s senior—was to have a decisive influence on Meunier’s artistic outlook.[6] When Degroux died unexpectedly at age 45, Meunier appears to have hit a period of fundamental doubt, one which Vandepitte also ascribes to financial worries and the need to establish a clientele (24). This was clearly apparent in the section “Bourgeoisie,” which grouped a set of genre scenes devoted to the world of the middle class. Especially surprising was The Visit (ca. 1870–75), hung near the later portrait of Meunier’s daughter Jeanne (ca. 1885), which is similar in terms of imagery, if not style. Both show an elegantly attired, wistful young woman posing in a bourgeois interior: an entirely atypical subject for Meunier, modeled obviously after the genre scenes that had earned Alfred Stevens (1823–1906) fame in Paris in the years previous.[7] In fact, The Visit is wholly reminiscent of Stevens’ Departure for the Walk (1859), though Meunier cannot match the latter’s keen evocation of elegance and splendor (24).

The results were much more compelling when Meunier tried his hand at history painting in the course of the 1870s, as evidenced in the section “Common People,” so titled because the subjects again demonstrate Meunier’s concern for the heroism of the everyday, for the plight of the anonymous masses. This speaks clearly from the cycle of paintings devoted to the Peasants’ War of 1798, a phrase that refers to various skirmishes and revolts against the French occupation of the Southern Netherlands, in the area that today comprises parts of Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany. Meunier’s Episode of the Uprising in the Vendée (1872) is an easy stand-out, noteworthy for the bold, simplified outlines and loose application of paint (fig. 3). The work depicts a group of peasants armed with rifles, scythes, and pitchforks, rallying for the cause in a barren, snowy landscape before an outdoor crucifix. Meunier was less in his element when, a couple of years earlier, he painted his Allegory of the Death of Lincoln (1865), which was on view in the same section. The painting turned up only shortly before 1990 in a private collection in the United States, before being acquired by Michigan’s Grand Valley State University in 2002.[8] Though unremarkable from a technical point of view, it too stands as a testament to Meunier’s societal commitment with its central image of a family of newly freed black slaves paying homage to the fallen president, while on the right are represented the working people, who have also come to pay their final respects.

The Industrial Period, ca. 1880–1905

The next group of sections roughly corresponded to what constitutes the second half of Meunier’s career following the key turning point that occurred around 1880. At the end of the 1870s, Meunier encountered heavy industry firsthand when visiting the foundries, rolling mills, and other factories of the present-day province of Liège—and just like that, the middle-aged artist found what was to be his subject par excellence. What better way to demonstrate this than the striking Foundry of Seraing (ca. 1880), hung in the section “Steel and Glass Industry” (figs. 4, 5)? Deep within the infernal bowels of the foundry, men toil and moil, their glistening torsos cast in a strong chiaroscuro by the combined effects of fire and steam. Even today, the painting is a sight to behold; and though Meunier was far from the first to direct his attention to industry, it is easy to forget that his ability to infuse modern labor—and the modern laborer—with such grandeur was refreshingly new at the time, not to mention appropriately timely in an age marked increasingly by social turmoil.[9]

The shift in Meunier’s career was consolidated when, in 1881, he travelled through the so-called Black Country—an industrial region in Wallonia so named for the omnipresence of coal mines—in the company of the artist Xavier Mellery (1845–1921) and the writer Camille Lemonnier (1844–1913), in the context of the latter’s book project, La Belgique. For those aware of its significance, an original copy of the book could be found lying inconspicuously spread open in one of the display cases in the section “L’Art Moderne”; though surely it could have been awarded a place of greater centrality, ideally accompanied by a monitor, so as to let visitors digitally leaf through the book and examine the thirteen illustrations provided by Meunier.[10]

Just as Meunier began tapping into this treasure trove of imagery, he was briefly pulled away, for nothing less than a six-month stay in Seville, represented in the section of the same name (fig. 6). He was sent there in 1882 by the Belgian government, which entrusted him the assignment to copy a Descent from the Cross by a Flemish master, meant for a much contested Museum of Copies that would never come to be. Though Meunier was initially reluctant to set out for Spain, his stay proved to be a pivotal stage in his career; hence the reason why it was already the subject of a small scale exhibition in the Royal Museums in 2008–2009, during which time it was reviewed for this very journal by Marjan Sterckx.[11] The impression from the works gathered is that the visit offered Meunier a breath of fresh air, and reinforced the evolution begun in Belgium. The paintings made in Seville feel very much alive; the brushstrokes are more direct than ever before, the colors are more vibrant, and, perhaps most significantly, the ability to capture life around him has deepened (28).[12] A case in point is the chef-d'oeuvre The Tobacco Factory (1882–83), which shows a sea of female workers engrossed in their task, seated underneath the impressive vaulted ceilings of the Real Fabrica de Tabacos (fig. 7). Two other women are placed convivially together in the front right, and add a picturesque flavor to the scene, all the more so since the strap of one woman’s dress has slid seductively off her shoulder. More revelatory still was the selection of sketches and scribbles Meunier made in Seville, hung on the wall opposite. Though at first sight they may not appear noteworthy, they reveal an artist capable of rapidly capturing his impressions on paper, as well as an artist unafraid of trying his hand at different materials from charcoal and pencil to ink and gouache, and any combination thereof.

Sometime before his departure for Seville, Meunier had taken up sculpting again, and once returned, wholly re-energized, he finished a series of three-dimensional pieces that he presented at the 1885 exhibition of Les XX. Among these were wax prototypes for what were to become two of his most famous bronzes: The Puddler (1884/1887–88) and The Docker (1885/1893), presented in the retrospective’s sections “Glass and Steel Industry” (figs. 8, 9) and “On the Waterfront,” respectively (figs. 5, 6). The puddler—a laborer in the steel industry who was responsible for continuously stirring the liquid mass of raw iron—is shown seated in a moment of rest, in a pose Meunier would prefer for other figures as well.[13] An immeasurable exhaustion is apparent from his hunched back, limp left arm, and woeful facial expression. Just as impressive as this evocation of the man’s fatigue, moreover, is the representation of his physique, making it all the more surprising that Meunier’s laborers are seldom considered in terms of the male nude. The shirtless puddler is muscular, sure, but a classical athlete or hero he is not; his is a body hardened and worn by constant manual labor in the toughest of conditions.[14] Despite the attention paid to physical constitution, the artwork is also indicative of what critics and scholars have come to praise as Meunier’s “synthetic” gaze, through which the artist offered not so much an exact portrayal of an individual model, as a synthesis based on countless observations. The longer you examine the statue, the clearer it becomes that Meunier simplified forms and sacrificed unnecessary detail.[15] The same goes for the splendid Docker, who is shown standing confidently upright in an almost exaggeratedly graceful contrapposto, both hands grasping his sides.

Sculpture had changed since Meunier had last practiced it. In the course of the 1870s, Belgian sculpture had awoken from its “marble slumber”, to use Octave Maus’ (1856–1919) eloquent metaphor; and Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) had been rocking the art scene to its core, not just in Paris, but also in Brussels where, in 1877, Rodin had presented the infamous sculpture known today as The Bronze Age (28–30).[16] (Rodin and Meunier were to become good friends, with both supporting the career of the other in their respective home countries; this aspect of their friendship remained unexplored in the exhibition, save for a quotation of Rodin’s on a panel near the entrance and exit, calling Meunier “one of the most important artists of our century”.[17]) Meunier’s innovative series of sculptures immediately received a warm welcome in the contemporary art world; and with that, the tone was set for the second stage of his career (30). The section “L’Art Moderne” constituted an attempt at reconstructing the artistic circles in which Meunier dwelled, centering on the famous art journal founded by Edmond Picard (1836–1924) (fig. 10). On view were portraits, statuettes and busts of such distinguished individuals as Lemonnier, Picard, Emile Verhaeren (1855–1916) and Henry van de Velde (1863–1957); some book illustration projects; the foundation charter and original membership list of the Société Libre des Beaux-Arts; and a host of letters from and to other members of the artistic beau monde. Still, the overall impression was somewhat haphazard, and it was not always immediately clear why the item in question was chosen, and in what way it contributed to a better insight into the artist, especially for the average visitor who lacks the necessary prior knowledge. None of the letters, for instance, had been transcribed or summarized, and among the odder choices for inclusion were a postcard from Meunier to an “unknown recipient” and a letter to “Anon”.

Though in general, the direction of the exhibition was harder to distinguish in the latter sections, these did succeed well in demonstrating that Meunier never ceased devoting himself to the disciplines of painting and drawing, even if at this stage of his career the sculptures of industrial and agricultural laborers tended to eclipse the remainder of his artistic output. Gems included the two undated pastels of industrial sites at dusk that were hung side by side in the section “The Great Disaster,” titled The Furnaces and Coalmine by Night (figs. 11, 12). Both scenes are abandoned but for a lone figure leading a horse, and both stress the brute, poetic power of the industrial landscape, demonstrating Meunier’s affiliation with fin-de-siècle symbolism (31, 130-133). Another masterpiece is the Mine Triptych (ca. 1900), apparently based on drawings (or preliminary studies?) shown earlier in the exhibition, like On the Road to the Mine (1887) in the section “The Black Country” (figs. 13, 14). The monumental painting depicts the miners’ daily shift in three panels: in the middle, the men make their way to the mine under an ashen sky; on the left, they gather at the lift for their descent into the darkness; and on the right, they emerge after a long day’s work, dazed and drained. Technically, Meunier proved his command of color even in a muted, almost monochrome palette, while he applied the paint with loose, impressionistic strokes.

The triptych was on view in the final section of the exhibition. Named “Tragic Beauty,” this gallery included the mature work of the artist, the “archetypical representations of sorrow and suffering, internalized, dismal and dejected” (fig. 15) (33, author’s translation). The most striking sculpture on view there—and for good reason, one of the best known of Meunier’s works—was Firedamp (1888–90, fig. 16). While staying with a friend in 1887, Meunier witnessed the tragic outcome of the mining disaster of La Boule, near Quaregnon, in which a total of 113 laborers lost their lives. Meunier was present when the scorched bodies were brought up to the surface for identification, and in a quick drawing captured the moment when a mother recognized her son among the fallen. Later, while living and teaching in the city of Leuven, that sketch served as the basis for the monumental sculpture seen here. The incident is portrayed with such sincerity and humanity that it is easily elevated to a symbol of universal anguish, with a timeless quality underscored by referencing the Pietà.[18] The Prodigal Son (ca. 1892), showing a seated man clasping the face of his son kneeling before him, was another stand-out, made all the more poignant by the knowledge that not long after, in 1894, Meunier was to lose both of his sons, Georges (aged 24) and Karl (aged 30, himself a promising artist).

Oddly, little attention was paid to the project that occupied much of Meunier’s thoughts since 1890 at the latest, his Monument to Labor, which wouldn’t be erected until a quarter of a century after his death, in 1930.[19] A large, grayscale photograph was plastered on one of the section’s walls, but a diagram would have been welcome, or, at the very least, additional photographs of the different sides of the monument (which includes a total of four reliefs and five free-standing figures) (fig. 15). In fact, Meunier’s public monuments could have easily merited a section of their own: in addition to the Monument to Labor, there is the statue Father Damien (1894, installed in the church garden of the Brusselsestraat in Leuven), the Mower and Sower made for the Brussels Botanical Garden (1897), the Horse at the Watering Place (1899–1901, installed on the Square Ambiorix in Brussels) and the Monument to Emile Zola (of which a plaster model was displayed from 1905, the year of Meunier’s death).[20] I was, however, pleasantly surprised to find the Great Miner (1900) included in the section, since until recently it was kept in the reserves of the Meunier Museum in Ixelles. The small scale bronze—its name indeed appears to be almost ironic given its modest dimensions—is remarkable because not only is the figure almost entirely nude, but also his wiry body is one of, if not the most individualized of Meunier’s figures, showing chest hair to boot.[21]

When exiting the exhibition, the visitor was greeted by three display cases and a final notice, which were meant to clarify the technical aspects of sculpting, specifically molding processes and bronze casting. Placed outside of the actual exhibition space, however, this tiny semi-section could not help but feel like somewhat of an afterthought. It might have been a better option to integrate the explanation into the actual retrospective, and, at the very least, to highlight different materials used in the sculpting process when actually presenting Meunier’s creations. An especially nice touch might have been to provide reproductions—say of a croquis and a bronze—for the visitor to feel and touch, as was the case in the retrospective of the French sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827–1875) in the Musée d’Orsay, in 2014. Though this semi-section was indicative of the occasionally incoherent set-up of the exhibition as a whole, it concluded a commendable fresh look at one of the fixtures of the Belgian nineteenth-century art world, hopefully paving the way for many more exhibitions in the Fin-de-Siècle Museum.

Thijs Dekeukeleire

Visiting professor at the Ghent School of Arts

thijsdekeukeleire[at]hotmail.com

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to the editors of Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide and to prof. dr. Marjan Sterckx for their helpful remarks.

[1] Sura Levine and Françoise Urban, Hommage à Constantin Meunier, 1831–1905 (Antwerp: Pandora, 1998), 11.

[2] Pierre Baudson, “De voorstelling van de arbeid in de beeldhouwkunst: Omtrent Constantin Meunier,” in De 19de-eeuwse Belgische beeldhouwkunst [19th-century Belgian Sculpture], ed. Jacques Van Lennep (Brussels: Generale Bank, 1990), vol. 1, 219.

[3] Grove Art Online, s.v. “Meunier, Constantin,” accessed May 18 2015; Levine and Urban, Hommage, 31.

[4] For an interesting essay on the 1909 retrospective, see: Sura Levine, “Constantin Meunier’s Monument to Labour at the 1909 Meunier Exhibition in Leuven,” in Constantin Meunier: A Dialogue with Allan Sekula, ed. Hilde Van Gelder (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2005), 11–18.

[5] Pierre Baudson, “Meunier, Constantin,” in De 19de-eeuwse Belgische beeldhouwkunst [19th-century Belgian Sculpture], ed. Jacques Van Lennep (Brussels: Generale Bank, 1990), vol. 2, 497.

[6] Levine and Urban, Hommage, 13; Baudson, “Meunier,” 499.

[7] For the Alfred Stevens exhibition review in this journal, see Marjan Sterckx, “Alfred Stevens,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 9, no. 1 (Spring 2010), accessed May 14, 2015, http://19thc-artworldwide.org/spring10/alfred-stevens.

[8] Levine and Urban, Hommage, 15.

[9] Baudson, “De arbeid,” 221ff.; Levine and Urban, Hommage, 21.

[10] Levine and Urban, Hommage, 17.

[11] Marjan Sterckx, “Constantin Meunier in Sevilla: De andalusische ouverture,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 1 (Spring 2009), accessed May 14, 2015, http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring09/constantin-meunier-in-sevilla-de-andalusische-ouverture.

[12] Grove Art Online, s.v. “Meunier, Constantin,” accessed May 18 2015; Baudson, “Meunier,” 499.

[13] Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal [Dictionary of the Dutch Language], s.v. “puddelen,” accessed May 18 2015; M. Waller, quoted in: Baudson, “De arbeid,” 218.

[14] Thijs Dekeukeleire, “Tussen naakt en bloot: Constantin Meuniers Grote Mijnwerker en het negentiende-eeuwse mannelijke naakt,” Article: Studiarttijdschrift 14 (Spring 2015), 10–13.

[15] Micheline Jerome-Schotsmans, Constantin Meunier: Sa vie, son œuvre (Brussels: Bertrand, 2012), 156, 293, 347; Baudson, “De arbeid,” 219; Gisèle Ollinge-Zinque, ed., Les XX en La Libre Esthétique: Honderd jaar later [Les XX and La Libre Esthétique: One Hundred Years Later] (Brussels: Royal Museums for Fine Arts of Belgium, 1993), 456, 458, 466, 486, 498.

[16] Octave Maus, “L’Exposition Centennale de l’Académie des Beaux-Arts,” L’Art Moderne 20, no. 50 (1900): 399.

[17] Frédéric Leseur, “Rodin en Brussel: Kroniek van een lange vriendschap,” in Brussel: Kruispunt van culturen [Brussels: Crossroads of Cultures], ed. Robert Hoozee (Antwerp, Brussels: Mercatorfonds, Paleis voor Schone Kunsten, 2000), 114-116; Marjan Sterckx, “Constantin Meunier and Leuven (1887–1897): A Love-Hate Relationship,” in Constantin Meunier: A Dialogue with Allan Sekula, ed. Hilde Van Gelder (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2005), 19–58.

[18] See for instance: Levine and Urban, Hommage, 27–29; Baudson, “De arbeid,” 223–224.

[19] Baudson, “De arbeid,” 232; Baudson, “Meunier,” 500; Levine and Urban, Hommage, 31; Levine, “Meunier’s Monument,” 11–18.

[20] Like the Monument to Labor, the Monument to Emile Zola would be installed only posthumously, in 1924 on the Avenue Emile Zola in Paris, but would sadly be lost in the Second World War. See: Baudson, “Meunier,” 503; Levine and Urban, Hommage, 33.

[21] Dekeukeleire, “Tussen naakt en bloot,” 10–13.