The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

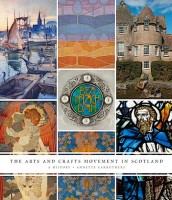

Annette Carruthers,

The Arts and Crafts Movement in Scotland: A History.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013.

424 pp.; 100 color and 250 b&w illus.; notes; bibliography; index.

$85.00

ISBN 978-0-300-19576-7

Craft and the nature of materials, joy in work and ethical making, regionalism and internationalism: these three sets of familiar themes have predominated in the literature on the Arts and Crafts movement. The myriad studies with titles beginning “The Arts and Crafts Movement in . . .” suggest that scholars have tended to focus on the movement’s regional inflections even as they have acknowledged the many international connections of its practitioners, institutions, and ideals. Annette Carruthers’ book, The Arts and Crafts Movement in Scotland, is another contribution to this genre. The book examines how Scottish designers and artisans approached the task of reforming artistic production by rethinking connections to Scotland’s regional traditions as well encouraging the broader, unbounded reach of their movement’s ideals. The contradictions, apparent or theoretical, that accompanied this approach have tended to be overlooked in favor of a celebratory focus on the movement’s social and artisanal ideals. Carruthers’ book deals forthrightly with the relationship of Scottish identity and internationalism, showing how close connections were forged with England, in particular. This finding will not surprise anyone, but the book adds to the literature by providing a substantial account of these ties. The shortcomings of this book stem from a different source: too little critical exploration of the Arts and Crafts ethos and practice.

Carruthers has been writing about the movement for many years, developing a deep familiarity with the full range of Arts and Crafts production in Scotland, from textiles and books to furniture and buildings—what has been dubbed the movement’s “polymath ideal.”[1] The sheer breadth of Arts and Crafts activity demands a full arsenal of historical tools. That many of the prominent studies of the Arts and Crafts movement have been exhibition catalogues (in addition, of course, to monographs on individual designers) suggests that scholars have had some difficulties applying these tools to its manifold aims and diverse production. The focus on individual objects or careers has provided easier navigation of the movement’s intricacies than approaches tackling issues that cut across genres, media, and personalities. Here, within the bounds of the conventional survey approach, Carruthers demonstrates a solid grasp of, and evident interest in, every dimension of the Arts and Crafts movement.[2] If there is a dominant genre in her book, it is architecture, and only because Arts and Crafts building encompassed a broad range of skilled work.

Carruthers’ story about the Arts and Crafts in Scotland helpfully begins with an overview of the wider British—primarily English—movement. It then situates Scotland’s changing economic and cultural position vis-à-vis Britain in the period from 1880 to 1930. Although the phrase “Arts and Crafts” was not formally used until 1887, when the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society was founded in London, Carruthers looks to an earlier generation of designers, writers, and social reformers who had a formative impact on the movement. Her story of origins encompasses the familiar figures: William Morris, A. W. N. Pugin, John Ruskin, and Thomas Carlyle, among others. Chapters one and two provide schematic outlines of their thought and its impact on British design from the 1850s through the early 1880s. This is well-traversed ground, but Carruthers’ contribution is to show that Scottish designers were early acolytes of the Morris Movement, a label the author usefully cites (if only once in chapter one) to remind us of the movement’s enduring inspiration and animating spirit. Chapters one and two suggest that Scottish artists and critics were quick to pick up on Morris’ writing in particular, but the paucity of specific references to published reactions at the time gives readers little sense of what they might have found so compelling in Morris’ polemics. The discussion also would have benefited from more clearly delineating the various strands of design reform, not all of which shared the arch-moralism or steadfast emphasis on hand-craftedness of the Arts and Crafts progenitors.

According to Carruthers, it was in the late 1880s that a younger generation of designers took up and popularized the cause of Morris and Ruskin. After the two introductory chapters, the book tracks this broadening and deepening of the movement both chronologically and geographically, proceeding in separate chapters that focus on a limited time-frame in either the large cities or the countryside and smaller towns. Thus, there are two chapters on the 1890s, two on the period from 1900 to 1914, and a chapter surveying production across Scotland during and after World War I, up to 1930. The vitality of Arts and Crafts work into the late 1910s and 1920s reminds us again that there were important cultural continuities between antebellum and postbellum Europe. The discussion of this late work also provides more evidence for understanding how economic and political changes were negotiated among artists and artisans in the early twentieth century outside the major European capitals, a field in which much comparative study can still be done.

Between the chapters on the 1890s and early 1900s is an interlude of four thematic case-study chapters covering the artist Phoebe Anna Traquair, architect Robert Lorimer, W. R. Lethaby’s Melsetter House, and the medium of stained glass, respectively. Carruthers reveals the important place of stained glass in Scottish Arts and Crafts, the origins of which she traces to the controversy over the installation at Glasgow Cathedral of glass imported from the Royal Bavarian Glassworks from 1859 to 1864. Because it sustains a cogent analysis of the interconnected issues of regionalism and internationalism, the economics of craft production (even if at a very basic level), and the aesthetic principles of the movement, it is the best single chapter in the book. Overall, these thematic chapters are the book’s most successful: the focus on inherently interesting subjects enlivens the more or less unvarying chronological procession of names and projects that characterizes the rest of the book.

A great benefit of organizing the material by time and geography is comprehensiveness of coverage. All of the major and many minor figures find their place in the book with at least one accompanying illustration. There is also some flexibility in the arrangement of material within each chapter according to themes, so that stylistic, institutional, or personal connections are discussed across discrete periods of time. By the end, the reader has surveyed a large quantity of production, traversed the countryside and the major cities of Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen, and Dundee three or four times over, and encountered a long roster of artists and patrons. As the endnotes and bibliography attest, Carruthers has assimilated a sizable specialized literature. This impressive feat constitutes an argument that the Arts and Crafts movement in Scotland was a definite historical phenomenon with reasonably clear contours, actors, and timeline. This has not been the view of all commentators. For instance, an important survey of Scottish architecture by Miles Glendinning, et al., eschews the Arts and Crafts label entirely and instead puts most of the architectural work discussed by Carruthers, and much else, into the catch-all category of “Traditionalism.”[3] Carruthers’ book makes it a tough sell for others who would deny Scotland its Arts and Crafts.

If the book succeeds in bringing new material to a wider audience and in establishing reasonable boundaries around its subject, it nonetheless falters in several ways that blunt its effectiveness and insights. We are told, in what amounts to the book’s thesis, that “Scottish artists, architects, designers and makers played a vital role in an extraordinarily rich cultural movement that transformed British architecture and changed the design of everyday things” (xv). This is both a sweeping and unremarkable thesis. Such shallow interpretive waters do not provide enough current to sustain a book as long and as wide in scope as this one. Contributing to this unambitious argument is an overly simple conception of the Arts and Crafts, as well as a serious deficit of interpretive analysis. And, despite the author’s insistence on the collaborative aspect of the movement, this is a book primarily about individual creators and their singular products. As a result of all these factors, the text largely reads as a roll-call of artists, projects, and craft products.

Many of these troubles are first evident in chapters two and three, which are made to do a lot of work. These chapters review the origins of Arts and Crafts practice in Scotland in the 1860s and 1870s, consider Scotland’s contributions to broader British developments, and survey the decade of the 1880s when the movement “truly came into existence” (39). For Carruthers, the most important early influences on the Arts and Crafts in Scotland were Philip Webb’s Arisaig House of 1863; Morris’ stained glass at Old West Kirk in Greenock, begun in 1865; the Morris-designed textiles of Alexander Morton & Co. in Darvel, Ayrshire; and the architectural work of Robert Rowand Anderson in the 1870s. But as a champion of the Scots, she is overzealous in arguing that “Scottish attitudes were essential to the development of the beliefs that underpinned the activities of Morris and his colleagues” (37). Little direct evidence of foundational or catalyzing “Scottish attitudes,” which remain undefined, is presented in these chapters, and it is a big leap to claim that they played any role in forming the beliefs or directing the activities of Morris and his collaborators. Although she paints in overly broad strokes, readers can, however, agree with Carruthers that “Scots were enthusiasts for Arts and Crafts ideas from the very first stirrings of the Movement” (37).

To categorize any particular work as part of the Arts and Crafts Movement requires “knowledge of the circumstances of its making,” as Carruthers writes. She continues, “‘Arts and Crafts is a method, not a style’ is another way to put this, but the style which resulted from Arts and Crafts method is easily copied and it is difficult to judge intention when confronted with solid reality” (13). This is a serious, though not insurmountable problem; unfortunately, it is ignored in the rest of the book. Objects and buildings are routinely categorized as “real” Arts and Crafts or merely “in the style of” the movement, but the reader finds few explicit criteria to separate the authentic from the superficial. This omission is especially egregious when the text turns, even briefly, to major architects and designers including the hard-to-categorize Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Edwin Lutyens, and Baillie Scott. Mackintosh and Scott, for instance, were usually identified with Art Nouveau, as Carruthers acknowledges. These three figures occupy the book’s fringes, but the (presumably good) reasons for sidelining their contributions to Arts and Crafts remain as obscure as their professional or personal identities in this book. Their ambiguous position also highlights the ambiguity of the distinction between the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau more generally. It would be too much to ask Carruthers to resolve this many-faceted issue in a book only about Scotland, and she was right to not attempt it. However, except for one paragraph where she notes that because Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau “shared many features” it “complicates the matter” of distinguishing them easily, Carruthers disregards the complexity of the issue (16). This has the effect of giving readers who are not deeply familiar with the literature the false impression that there is a clear-cut division between Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau.

The brief discussion of Lutyens' design for extensions to the Georgian Ferry Inn at Rosneath, Argyllshire, commissioned by Princess Louise in 1896, is a typical case of the too-simple view of Arts and Crafts production. Except for some very general and brief comments about its adoption of local materials and vernacular-inspired forms, the author never says what exactly makes the work part of the Arts and Crafts movement, and the claim is put forward that its “broad horizontality” made it “less Scottish in form” (126). But if it eschews a regional or national inflection, is it necessarily less Arts and Crafts? And what about its method of construction? In Arts and Crafts criticism, building method usually counted for more than mere style. But if it is less artisanal, is it closer to Art Nouveau? The discussion, however, remains stuck in generalizations about style. The author concludes that Lutyens “later moved away from the Arts and Crafts towards classicism, though he always felt strongly about the right use of local materials and joined the Art Workers' Guild in 1903” (126). Elsewhere, Carruthers writes that Lutyens was “not entirely in tune” with the Arts and Crafts (304). So, where does this leave Lutyens in the larger account? If the questionably Arts and Crafts Ferry Inn project was followed by work that was unambiguously not part of the movement, why include Lutyens at all? He should rather be confined, if even mentioned, to a passing reference to his interest in vernacular form, or to the endnotes. The author’s reasons for including discussion of two of his works remain as unclear as his status in relation to the movement. As the Lutyens examples demonstrate, the lack of engagement with substantive issues as well as the lack of clarity about the boundaries of the Arts and Crafts label undermine even the utility of the descriptive passages since the reader is given few tools with which to analyze buildings and objects and no clear criteria with which to identify genuine Arts and Crafts work.

In the case of architecture, little attention is paid to issues other than style and the identification of materials. Numerous opportunities are passed over to proffer more critical, analytical reflections. Thus, for instance, in the description of Robert Lorimer’s “restoration” work at Earlshall in Fife we find no discussion of what restoration, as opposed to creative interpretation of historical fabric, meant to Arts and Crafts architects. According to Carruthers, Lorimer’s “decision to leave the walls bare shows his interest in the texture of stone and a lack of concern about revealing—or a desire to indicate—where alterations had been made in the past, whereas the harled surface at Glenlyon presented an ‘as new’ appearance” (119–20). Several critical issues implicitly raised in this short passage—about restoration, materiality, and “age value”—are left unexplored.

While the book’s chronological organization provides a sense of development over time and highlights the role of artistic influences, the organization of material into alternating city and country chapters provides fewer compelling insights. Instead, the arrangement stifles the narrative and contributes to its episodic, catalogue-like quality. The differences in patronage, social context, style, and production between Glasgow and Edinburgh emerge as possibly more interesting and substantial than do the differences between city and country. There are references to the individual characteristics of Glasgow and Edinburgh in a number of places, but they do not cohere into a clear picture.

The emphasis on large exhibitions is more fruitful. Their instrumentality in raising public awareness of Arts and Crafts ideals and in bringing together artists and craft workers from across the country are recurring themes. The focus on the planning of exhibitions and on cataloging items and exhibitors leaves less room, it must be admitted, for the discussion of small-scale amateur or “home industries” production, which is much more difficult to document and assess since it requires sources other than the catalogues and art journals that recorded and commented on the exhibitions. This trade-off notwithstanding, the sections on exhibitions, and the related issue of institutional support for craft and artisanal work, are some of the most satisfying.

Carruthers spends more time on the Edinburgh Art Congress of 1889 than any other single event or work, except for the chapter on the Melsetter House and the penultimate section on the Scottish National War Memorial at Edinburgh Castle. Marking the “real beginning of the Arts and Crafts Movement in Scotland”, the 1889 congress of the inelegantly-named National Association for the Advancement of Arts and Its Application to Industry (NAAAAI) was organized to bring artists, craft workers, and manufacturers together to discuss ideas for changing the standards of British manufacturing of decorative products (63). The NAAAAI had first met a year earlier in Liverpool, but only “several Scots” attended then. At the Edinburgh meeting, William Morris chaired the decorative arts section, and Scots were better represented. It had been thought that the “considerable social prestige” of the organization would lead to nothing but positive effects in Scotland (64). Carruthers’ account, however, shows that the meeting was poorly organized; only about 500 attended, whereas the Liverpool meeting had attracted over 2,000 people. Morris himself considered it a failure, writing to his daughter that it “has not been much of a success” and noting with dismay that he had sat through “some monumentally dull papers” (65).

But the biggest disappointment was the failure to raise interest among manufacturers. Even the artists “remained split on the value of commercial production in competitive industry” (67). In fact, the failure of Scottish Arts and Crafts champions to attract manufacturing interest emerges as a key to understanding the limitations of the movement. A fuller discussion of the issue would help clarify the issues at stake and examine the reasons for the Scottish movement’s failure to engage industry. The measurable effects of the exhibitions, then, were rather local and diffuse. Certainly, they forged connections between Scottish and English artists and publicists within the movement. They helped crystallize the aims and achievements of designers and craft workers and brought wider public awareness of the issues. And they supported “the reassertion of the dignity of the work of the arts of decoration,” in the prepositionally immoderate words of Edinburgh University art teacher Gerard Brown (68). But these were unsystematic achievements; artistic “connections” and “assertions of dignity” are both hard to document and difficult to evaluate.

As a whole, Carruthers’ book has the rudiments of a good survey, but the manuscript needed a much stronger editorial hand to strengthen its interpretive content and enliven its narrative. As it stands, the whole is less than the sum of its parts. Its contribution lies in bringing together a large amount of material in one volume, ably demonstrating the fecundity of this episode in Scottish design history. And the book itself is a lovely product. Thin lines frame the top and outer margins of each page, creating an effective visual enclosure. As we expect from Yale art books, the production value is high, and well suited to the work it presents. It may not be itself a handcrafted object, but it nicely evokes the Arts and Crafts ethos. Yet, because of its perfunctory narrative and lack of interpretive curiosity, The Arts and Crafts Movement in Scotland falls short of its promise to be an authoritative account.

Paul A. Ranogajec

Independent art historian

New York, NY

pranogajec[at]gmail.com

[1] Elizabeth Cumming and Wendy Kaplan, The Arts and Crafts Movement (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 87.

[2] In this regard, she furthers the tradition of broad expertise shown by a number of recent Arts and Crafts specialists. See, for instance, ibid.; and Cumming, Hand, Heart and Soul: The Arts and Crafts Movement in Scotland (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2006); Cumming, Phoebe Anna Traquair 1852–1936 (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2005); and Alan Crawford, C. R. Ashbee: Architect, Designer and Romantic Socialist (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985).

[3] Miles Glendinning, Ranald MacInnes, and Aonghus MacKechnie, A History of Scottish Architecture from the Renaissance to the Present Day (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), 334–84.