The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

L’Art Nouveau: La révolution décorative

Pinacothèque de Paris

April 18–September 8, 2013

Exhibition catalogue:

Marc Restellini, artistic director; with contributions by Victor Arwas, Paul Greenhalgh and Dominique Morel.

L’Art Nouveau: La révolution decorative.

Milan: Pinacothèque de Paris and Skira, 2013.

40 € (hard cover)

ISBN: 978-8-857219-50-9

The Pinacothèque de Paris is assuredly an unexpected addition to the museum community of Paris. Founded by art historian Marc Restellini in 2007, this private museum flies in the face of French museum culture on several fronts. First, it is privately funded and operated. Second, it showcases temporary exhibitions that cover whatever time period and historical style the organizers wish to present; offerings have included everything from Roy Lichtenstein (2007) to The Soldiers of Eternity (2008) featuring the Xi’an terra cotta warriors. And third, the exhibition space is located in a re-purposed building adjacent to a gourmet food market on the fashionable Place de la Madeleine. In 2011, the Pinacothèque expanded to another building nearby on the rue Vignon (fig. 1); and in May 2013, the museum announced plans to open the Singapore Pinacothèque de Paris in an historic colonial building in the local arts district.[1] In short, the Pinacothèque de Paris has created an entrepreneurial model for museums, which is extremely rare in France.[2]

In 2012, the Pinacothèque began presenting two related exhibitions simultaneously, starting with Van Gogh: Dreaming of Japan and Hiroshige: The Art of Travel.[3] The second pair of exhibitions opened last spring with Tamara de Lempicka: La reine de l'Art déco and L’Art Nouveau: La révolution décorative. These two exhibitions were presented separately and developed by independent curators, but linked by the historical progression from art nouveau to art deco. This review focuses exclusively on the art nouveau exhibition.

It must be noted at the outset that L’Art Nouveau: La révolution décorative focused exclusively on French decorative arts and on three major collections from Gretha and Victor Arwas, Robert Zehil, and the Mucha Trust. In keeping with art nouveau’s characteristic blurring of the lines between artistic disciplines, the 200+ objects on display encompassed both traditional decorative art forms, such as furniture, glass, and ceramics as well as popular commercial products, such as advertising posters and luxury goods like custom-made jewelry. Sculpture, drawings and paintings were also represented in a variety of media. Pinacothèque director Marc Restellini describes the show as the “first French Art Nouveau retrospective in Paris since 1960,” perhaps a surprising observation in light of several major exhibitions on the subject in more recent years.[4] For example, the Pinacothèque’s guest curator, Paul Greenhalgh, organized Art Nouveau, 1890–1914 in 2001 during his tenure as Head of Research for the Victoria and Albert Museum, an exhibition that also traveled to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. where it introduced a new generation of Americans to the art and ideas behind this early modern movement. Likewise, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam has made a number of contributions to the subject of art nouveau with the 2004 exhibition, L’Art Nouveau: The Bing Empire, guest curated by Gabriel P. Weisberg of the University of Minnesota, and the 2007 show Barcelona 1900, guest curated by Teresa-M. Sala of the University of Barcelona.[5] In addition, there have been a number of exhibitions centered on the role of Japonisme in art nouveau as well as the importance of Montmartre as the urban heart of avant-garde culture in fin-de-siècle Paris. Given this abundance of both scholarly research and public appreciation, it is startling to learn that the Pinacothèque de Paris exhibition is the first French retrospective in over fifty years.

Paul Greenhalgh, now the director of the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts at the University of East Anglia, organized L’Art Nouveau: La révolution décorative around four themes: “The Role of Nature”; “Sense and Sensuality: Eroticism”; “Modern Mysticism”; and “Selling the New Style”. Within the modest gallery spaces located on two separate levels, this thematic structure allowed visitors to consider the ideas and concerns that prompted the emergence of art nouveau within the context of the complicated, intertwined social, technological and economic changes of the decades surrounding 1900.

The exhibition opens with one of Alphonse Mucha’s theatrical posters, La Dame aux camélias (1896, Mucha Trust, Prague), flanked by didactic panels on either side (fig. 2). Immediately to the right of the compelling image of Sarah Bernhardt as Marguerite Gautier is a large scale, three-column text by Restellini that reproduces his introduction to the exhibition catalogue. Although it offers visitors a clearly written overview of the exhibition, it also requires that visitors stop for some time in order to read a sizeable amount of text in one location, potentially creating a crush of people at a point when they are just beginning to enjoy the show. The didactic panel to the left of the Mucha poster is more succinct, offering specific information about the genesis of art nouveau as well as a statement about its international scope and its relative place in the history of art. One quibble that this reviewer had with this panel, however, is that although there was a reference to the creation of the term “art nouveau” and an even more specific reference to the seminal gallery known as La Maison de l’Art nouveau, there is no credit given to Siegfried Bing, the man who was responsible for both coining the term and creating the gallery. Since Bing’s contribution is covered extensively in the exhibition catalogue, this seems an odd omission in the explanatory text for the public.

Moving into the display areas, there is another didactic panel on “Le rôle de la nature” [The role of nature] (fig. 3). Here, the viewer is introduced to ‘nature’ as understood within the emerging context of scientific inquiry into evolutionary development. Greenhalgh’s discerning catalogue essay “Le style de l’amour et de la colère: L’Art nouveau hier et aujourd’hui” [The style of love and anger: Art nouveau yesterday and today] explains the changing perceptions of the natural world as a source of inspiration. He points to nature as a primary principle of art nouveau, and notes that Darwin’s publications, particularly The Descent of Man (1871), altered our understanding of how humanity fits into the scheme of things. No longer was humanity perceived as the pinnacle of God’s creation, but rather as a part of nature similar to any other species. This revised positioning of humanity led to an interest in transformation images (women becoming furniture being only marginally different from Daphne turning into a laurel tree in ancient Greece) as well as fantasy imagery that linked sexuality and cruelty with the forces of natural selection (16–17).

The inspiration of nature in art nouveau decorative arts becomes clear as the viewer peruses the niches and vitrines of the first gallery space. The dim lighting of the gallery and intimate scale of the spaces allow visitors to experience the objects in close proximity, as in the example of the enamel and wrought silver bowl on top of Eugène Gaillard’s display table (fig. 4). The large bowl (1895, private collection) designed by Lucien Hirtz for the distinguished jeweler Frédéric Boucheron reveals a combination of sea creatures (dolphins perhaps) on the wrought silver handles with an enameled image of a woman swathed in leaf-like forms on the bowl itself (fig. 5). Although the bowl is loosely based on the paintings of Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, who created a number of images featuring wind-blown women in fall landscapes, Hirtz’s image is both more abstract and more sensual as the woman emerges from a watery realm into the swirling leaves of the air.

In a nearby vitrine, Charles Vital-Cornu’s bronze vase Sommeil [Sleep] (ca. 1900, private collection) continues the theme of women’s connection to the natural world with a bas-relief of a sleeping figure beneath extravagantly modeled organic forms ringing the top of the vessel (fig. 6). To the left of Sommeil are two Vases Coquillage [Shell Vases] (1900, private collection) by the Atelier de Glatigny, a ceramics studio established in the 1890s to produce high quality objects at affordable prices. Like Sommeil, these two small porcelain vessels on silver bases possess a dramatic presence that stems in part from the curving forms, which in this case are complemented by the naturalistic appearance of the glazing. In contrast, Georges de Feure (1868–1943) used an understated porcelain form for his 1902 Vase (Collection Robert Zehil, Monte Carlo) but covered it with the images of abstracted flowers, water, and a swan expressed through the use of arabesque lines so often associated with art nouveau.

The theme of nature continues into the next gallery where the work of architect and designer Hector Guimard (1867–1942) is celebrated with two vases and a clock, all from the collection of Robert Zehil (fig. 7). The visitor is introduced to Guimard through another wall-mounted didactic panel that provides a brief discussion of his architecture and then notes that he also designed ceramics, metalwork, and furniture. None of this information pertains specifically to the works on display in the exhibition, thus allowing the viewer to approach each object without preconceived ideas about how to interpret the art. Whether or not this strategy is appreciated by museum-goers remains an open question. Guimard’s small stoneware vase from 1900 invites interpretations of its abstract glazes in much the same way that clouds evoke whatever shapes and forms the viewer perceives; it seems to suggest both crystals forming and leaves falling (fig. 8). Ten years later, when he designed the bronze vase and clock, Guimard’s style had begun to evolve into smoother forms. The 1910 vase presents a more conventional shape with deeply sculpted curves culminating in undulating forms at the rim. In comparison, the bronze clock is an exercise in refined understatement with its crisp lines and smooth, easy curves.

Art nouveau glass is presented in the next grouping, introduced again by a large didactic panel entitled “Une forêt de verre” [A forest of glass]. French glassmakers during this time conducted sophisticated investigations into new production techniques as well as new aesthetic concepts, and ultimately created a new design vocabulary for modern art glass. Dominque Morel’s catalogue essay on “Le verre Art nouveau: De Gallé à Lalique” [Art nouveau glass from Gallé to Lalique] provides a useful guide to the major figures in this movement, with detailed discussions of each designer’s contribution to the discipline (30–37).

The city of Nancy in the eastern French province of Lorraine was one of the most important centers for art nouveau glassmaking; it was here that both Gallé and Daum Frères were based, and it was here that the scientific knowledge of glass production was frequently combined with experimental design work. A grouping of three vases spanning 1895–1900 illustrates this development clearly (fig. 9). The earliest of these vases is by Burgun Schverer & Cie, and entitled Chardons [Thistles] (1895, Collection Robert Zehil, Monte Carlo). The conventional form of this piece serves as a blank slate for the combination of swirling red and green-colored glass overlaid with an asymmetrical placement of raised thistle plants. The choice of thistles as a motif is equally unorthodox; it is not a charming poppy or dreamy rose, but a prickly herb that rarely provokes delight. It, however, does speak to the edginess that is part of the art nouveau designer’s understanding of nature as a force that is often filled with difficult challenges.

The other two vases in this grouping also demonstrate a willingness to experiment with techniques in order to produce compelling design. The small pedestal vase by Eugène Michel (1900, Robert Zehil collection, Monte Carlo) offers a cloudy glass surface against which the designer has placed opaque fish and plant life as if to suggest an underwater view of the scene--an unexpected perspective courtesy of the designer. Also from 1900, Emile Gallé’s Vase (Robert Zehil collection, Monte Carlo) is far less literal in conception than the other two vases in this display; rather, the abstracted eddy of colored glass animates the ever-widening vase with increasingly light, bright colors; as with Guimard’s stoneware vase from 1900, the interpretation of the imagery is entirely up to the viewer. One last example of innovative glass is the Vase (1890, Robert Zehil collection, Monte Carlo) by François-Eugène Rousseau (fig. 10). Designed at the very end of Rousseau’s career, this work reflects the influence of Japanese design in both the subject matter of fish swimming through seaweed and in its use of a seemingly unintentional dripping blue glass at the rim. By allowing this blue glass element to appear random and imperfect, Rousseau embraced the apparently arbitrary processes of nature, a characteristic also found in the Japanese wabi-sabi aesthetic.

The next grouping of objects addresses the theme of sensuality and eroticism in art nouveau objects. Here too, the explanatory panel provides an introduction to the topic and substitutes for detailed labels adjacent to the artworks. A close look at one of the vitrines reveals some rather traditional subject matter—the classical figure of Juno as well as the Judeo-Christian Adam and Eve—but the handling of these stories takes on a decidedly erotic tone (fig. 11). In the foreground is a Sèvres porcelain figure entitled Le Rocher aux pleures [The Rock of Tears] designed by Hector Lemaire (1900, Victor and Gretha Arwas collection, London) depicting a nude weeping woman draped over a rock. Traditionally, this type of image would have reflected Homer’s ancient tale of Niobe, a Phrygian woman whose hubris resulted in the murder of her children. When she flees to Mount Sipylus, she is turned into stone and condemned to weep for all eternity.[6] Lemaire’s rendition of a weeping woman on a stone transforms this tale of the consequences of pride and maternal grief into a sensual tour-de-force of soft flesh against hard stone. The contours of the woman’s body are both elegant and erotic, and although the title implies that she is crying, the image suggests that she is perhaps simply shielding her face with her hair while she awaits someone who will appreciate her beauty.

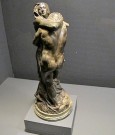

Louis-Auguste Théodore-Rivière’s patinated bronze sculpture of Adam and Eve (1903, Robert Zehil collection, Monte Carlo) in the same vitrine takes the implication of sexuality further into an overtly erotic expression (fig. 12). The exhibition catalogue lists two other titles for this work, Etreinte (Embrace) and Paradis perdu (Paradise Lost); both are less transgressive than Adam and Eve, a title that allows no room for speculation as to who this couple represents. The Genesis story is clearly illustrated in the couple’s erotic embrace, but the physicality of such obvious sexuality would have been in conflict with the nineteenth-century teachings of the church; the resulting tension thus underscores the contradictory—and subversive—impulses of art nouveau designers.

Following these explorations of sensuality and eroticism, the viewer moved along a narrow passageway hung with photographs of designers and key art nouveau locations (fig. 13). This led to a space featuring the American dancer Loïe Fuller (1862–1928) who became an overnight sensation when she first performed at the Folies-Bergère in 1892. Born in Hinsdale, Illinois, just outside of Chicago, Fuller pioneered modern dance forms by manipulating long panels of translucent silk with bamboo sticks. When she added colored theatrical lighting, the result was an enchanting potion of color, sound and light amid ever-shifting expanses of fabric. Not surprisingly, Fuller was drawn, painted, sculpted, photographed, and ultimately filmed by an extraordinary number of fin-de-siècle artists. Two bronze pieces in this exhibition attempt to capture the sense of excitement and sensual energy of Fuller’s performances (fig. 14). Bernard Hoetger’s Loïe Fuller (1901, Private collection) not only engages the viewer with the dancer’s billowing skirts, but also reveals her bare torso to the public, which was not a regular occurrence in Fuller’s performances (fig. 15). With her slightly awkward stance, she echoes the realism of Edgar Degas’s ballet dancers, but it is the externalized energy of her movement that animates the surrounding space and draws the viewer into her world. Similarly, the extravagant gilded bronze Lampe Loïe Fuller (1900, Victor and Gretha Arwas collection, London) not only conveys Fuller’s dynamism, but also seduces her audience with a seemingly unstable position and the outrageously ascending waves of hair (or is it fabric?).

Following the display of Loïe Fuller imagery, the exhibition examines the theme of mysticism in the modern world, again in the form of female figures representing a variety of both specific and abstract concepts. As the didactic panel explains, many spiritual, occult, and unconventional religious sects attracted increasing attention at the end of the nineteenth century as people reacted to the escalating number of changes brought about by industrialization and developments in science, medicine, and the new study of psychology. In fact, Greenhalgh notes that science and religion occasionally coalesced into “pseudo-science of ‘quasi-religion’” (21). An interest in spiritualist practices, such as sèances, or theosophy as promoted by the Russian occultist, Helena Blavatsky, or even the re-emergence of earlier concepts, such as vitalism, mesmerism, and rosicrucianism, were all reflections of the desire for a framework in which to formulate values that would make sense of a chaotic world.

New definitions of the role of women proved to be one of the most confusing aspects of modern life in France. Although French women enjoyed more freedom than many of their European counterparts, that did not make the process of achieving equality any easier. The dominance of the femme fatale in French culture was ample testimony to the anxiety produced by the concept of an independent woman—whether she was perceived as ‘dangerous’ or simply free of dependence on male support. Two sculptures in L’Art Nouveau: La révolution décorative illustrate this dichotomy distinctly. First is Emmanuel Villanis’s Dalila [Delilah] (1900, Victor and Gretha Arwas collection, London), a gilded patinated bronze figure with an ivory face (fig. 16). The story is a familiar one: Dalila betrays Samson to his enemies in exchange for money. Villanis’s sculpture, however, portrays Dalila not as an evil temptress with overt sexual attributes fully on display, but as a moody teenager, fully clothed except for the delicate beauty of her face. She embodies what Greenhalgh described in his essay as the hypnotic power of a “seductive nightmare” (20). She appears to be an alluring, and even sweet, young woman when she is, in fact, a calculating traitor. The anxiety produced by these contradictory elements is a strategy that art nouveau designers exploited to express their uneasiness about changing sexual mores and gender relationships.[7]

By comparison, Charles-Emile Jonchery’s portrayal of an allegorical female figure, entitled Le Vent souffle [The wind blows] (1900, Robert Zehil collection, Monte Carlo), suggests a free spirit unhampered by social restrictions (fig. 17). At two and a half feet high, the patinated bronze figure seems lost in dreams as the wind blows through her hair; even her rather skimpy clothing is decorated with plant forms that seem to grow out from the side seams and onto her shoulders; she is a creature of nature, and therefore, beyond the confines of patriarchal rules. She is less dangerous than Dalila, but certainly no more subservient. In the real world of French culture, it was the great actress Sarah Bernhardt who most directly embodied the “new woman” and, like Loïe Fuller, she was frequently the subject of paintings, sculpture, and posters. She made no distinction between male and female stage roles, playing Hamlet as well as Salomé or Phaedra, and causing much consternation in the process. In her sculpted self-portrait, however, she offers a frank, unglamorous image very different from the seductive and exotic actress of the Comédie Français (figs. 18 and 19). As an artist who routinely persuaded audiences to believe in magic, Bernhardt knew very well that it was all artifice.

The final section of the exhibition unfolds downstairs in another space where the primary focus is on “Vendre le nouveau style” [Selling the new style] (fig. 20). Again the didactic wall text provides the sole information about the objects in this gallery, glossing over the significance of this moment in time when fine art and commercial art begin to merge as well as the seminal role of Siegfried Bing and Julius Meier-Graefe. The Pinacothèque de Paris director, Marc Restellini, has said that people want object labels that contain “...intelligent information on the history of the artist and the work, something not too complex, but not oversimplified.”[8] These explanatory panels, however, offer visitors only the overview and virtually nothing about specific objects. And while the exhibition catalogue fills in many of the blanks, it is unlikely to be read while touring the galleries.

That said, this final gallery showcases some of the most famous images of French art nouveau—posters advertising Job cigarette papers, performances at the Folies-Bergère and Le Chat Noir, art exhibitions, and exposition openings; book illustrations; lithographs; and the Ecole de Nancy furniture of Emlie Gallé, Louis Majorelle, Emile André, and Gauthier Poinsignon. This gallery is more open than the upper level spaces, and thus, there is room to create vignettes displaying several large pieces of furniture as an ensemble (fig. 21). Likewise, the large-scale advertising posters are more legible when viewers can step back far enough to understand the full effect of the designs (fig. 22). In short, it is a grand finale of visual delight.

As the first exhibition on French art nouveau in Paris since 1960, this exhibition presents an overview of the complex themes of this style and historical period as well as a welcome glimpse into three private collections. The full-color exhibition catalogue expands and enhances the show with much needed analysis of the role of art nouveau in the context of fin-de-siècle modernism and art historical scholarship. The one question that remains unanswered—and is no doubt beyond the scope of this exhibition—is why there has been so little interest in art nouveau in Paris for the last half century.

Janet Whitmore

jwhitmore12[at]gmail.com

[1] Georgina Adam, “Paris Pinacothèque will open $24m outpost in Singapore,” Art Newspaper, May 25, 2013. See http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Paris PinacothC3A8que will open 2442m outpost in Singapore/29654

[2] For an interview with founder, Marc Restellini, see John Lichfield, “‘They have tried to destroy me’ says rising star of Parisian art world,” The Independent, March 1, 2010. See http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/they-have-tried-to-destroy-me-says-rising-star-of-parisian-art-world-1913687.html

[3] Overviews of both exhibitions can be viewed on the museum’s website at: http://www.pinacotheque.com

[4] Marc Restellini, L’Art Nouveau: La révolution décorative (Milan: Pinacothèque de Paris and Skira, 2013), 7. “L’exposition que nous présentons aujourd’hui est la première rétrospective de l’Art nouveau français à Paris depuis 1960.” Translation by the author.

[5] In addition to exhibitions specifically on the topic of art nouveau, there has been an abundance of material published on the closely related, although not identical, topic of Montmartre and its influence on the development of art and culture. See Philip Dennis Cate, The Spirit of Montmartre: Cabarets, Humor and the Avant-garde, 1875–1905, ex. cat. (New Brunswick, NJ: Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 1996); and Gabriel P. Weisberg, ed., Montmartre and the Making of Mass Culture, (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001). See also the seminal work by Debora L. Silverman, Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siècle France: Politics, Psychology and Style, (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989). Although it is outside the scope of this review, publications on Japonisme have also played a key role in furthering art historical understanding of how art nouveau developed.

[6] The story of Niobe is first written in Homer’s Illiad and later repeated in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, VI, 145–310. It may also be accessed courtesy of The Internet Classics Archive at: http://classics.mit.edu//Ovid/metam.html

[7] The employment of the “seductive nightmare” strategy began much earlier in the work of Henry Fuseli and Eugène Delacroix, among others, and it was extremely prominent in the poetry of Charles Baudelaire in the mid-nineteenth century. However, art nouveau artists created a whole genre of imagery related to the femme fatale and the association between sexuality and death or danger. See Elizabeth K. Menon, Evil by Design: The Creation and Marketing of the Femme Fatale (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2006).

[8] John Lichfield, “‘They have tried to destroy me’ says rising star of Parisian art world,” The Independent, March 1, 2010. See http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/they-have-tried-to-destroy-me-says-rising-star-of-parisian-art-world-1913687.html