The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Angels and Tomboys: Girlhood in 19th-Century American Art

Newark Museum

Newark, New Jersey

September 12, 2012–January 20, 2013

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art

Memphis, Tennessee

February 16–May 12, 2013

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Bentonville, Arkansas

June 29–September 30, 2013

Catalogue:

Angels and Tomboys: Girlhood in 19th-Century American Art.

Holly Pyne Connor, with contributions by Sarah Burns, Barbara Dayer Gallati, and Lauren Lessing.

Newark, N.J.: Newark Museum; San Francisco: Pomegranate Communications, 2012.

183 pp.; 102 color illus.; 34 b&w illus.; exhibition checklist; index.

$39.95

ISBN: 978-0-7649-6329-2 (hardcover)

The visual and material cultures of childhood have been the subject of several significant exhibitions during the past decade.[1] One of the most recent, Angels and Tomboys: Girlhood in 19th-Century American Art, organized by Holly Pyne Connor of the Newark Museum, offered an excellent overview of artists’ contributions to cultural discourses about girlhood during a period when girls and young women were increasingly popular subjects.[2] The exhibition showed artists exploring issues of race and social class, fashion and family, health and decorum, modernity and maturity as they sought to capture on canvas, marble, or paper what it meant to be a girl. Angels and Tomboys was divided into nine sections, with the first three largely comprised of images that presented a demure and passive model of girlhood. Works of art in the remaining sections offered visions of girls, including tomboys, adolescents, and members of the working-class, that were potentially disruptive of the angelic ideals defined in the preceding galleries. Connor did not oversimplify, however, by creating too hard a dividing line. In some cases, works that promoted an angelic ideal hung beside those in which halos were not as firmly affixed. Below each section title on the gallery wall a quotation from a contemporary text, such as Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868–69) or Marion Harland’s Eve’s Daughters; or Common Sense for Maid, Wife, and Mother (1882), provided a brief, but pointed, period voice on the subject of girlhood (fig. 1). The quotes were a clever reminder that paintings, sculptures and prints contributed to nineteenth-century ideals of girlhood just as surely as did popular novels and etiquette books, and that literary ideals influenced the production and reception of the works of art on display.

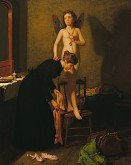

Angel (1887, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC), a serenely beautiful painting in which Abbott Handerson Thayer cast his eleven-year-old daughter Mary as an icon of purity, served as the exhibition’s leitmotif (fig. 2). The painting appeared on the cover of the exhibition catalogue and presided over the streets of downtown Newark, where her image rippled on banners celebrating the city’s cultural offerings (fig. 3). The painting hung on its own wall in the second gallery and was dramatically framed by the entrances to the first two galleries as you approached the exhibition (fig. 4). When I visited in December, the museum shop had installed a display table in front of the exhibition entrance, somewhat impeding the carefully orchestrated sight line, but likely increasing holiday sales. Angel still effectively beckoned, however, drawing the viewer forward as its altarpiece-inspired, gilt frame gleamed in the spotlights.[3]

The exhibition’s first section, “Childhood Androgyny ~ Is the Sitter a Girl or a Boy?” was designed to disrupt assumptions about the naturalness of twentieth- and twenty-first-century visual markers of children’s gender identity. The small gallery was filled with portraits that attested to the very similar manner in which younger girls and boys were represented in the early decades of the nineteenth century when “infants and young children were characterized as angelic and androgynous, since parents wanted to de-emphasize the sexual identity of their children” (29). This emphasis on asexuality was an outgrowth of the romantic ideal of childhood as a period of innate innocence and purity. For example, Ammi Phillips’ Boy in Red and Girl in Pink (both ca. 1832, Princeton University Art Museum) hung side by side, so that visitors could readily note the similarity in the children’s clothing, hairstyle, gaze, and even the strawberries they clutch as attributes (fig. 1). Wall text instructed viewers in how to decode the paintings, noting, for example, that the position of the strawberry over the girl’s womb is likely a reference to fertility, while the boy’s hammer alludes to his masculinity. Boys were often represented in more active poses, and flowers were popular for, but not exclusive to, girls. While the titles of the Phillips’ paintings revealed the sitters’ genders, the ambiguous titles of other portraits in this section, such as Erastus Salisbury Field’s Mrs. Paul Smith Palmer and Her Twins (1835/1838, National Gallery of Art), meant that viewers had to use pose and attributes to determine whether the subjects were boys or girls (fig. 5).

The visitor moved forward in time in the second section, “Attributes of Girlhood ~ Flowers, Pets and Dolls” (fig. 6). The majority of the paintings dated from the 1880s and 1890s, and included narrative scenes as well as portraits. A change in wall color from rich mauve to light yellow signaled the shift in focus. This section demonstrated the popularity of flowers, pets, and dolls in paintings that presented “girls as demure, domestic, dependent, and sweet” (29). William J. McCloskey’s Feeding Dolly (If You Don’t Eat It, I’ll Give It to Doggie, (1890, Hudson River Museum) demonstrated the importance of dolls as symbols of and tools for the production of future domesticity (fig. 7). Frank Duveneck’s portrait of Mary Cabot Wheelwright (1882, Brooklyn Museum), in which there is an uncanny resemblance between the young sitter and the doll she clutches, revealed the way in which girls themselves were frequently portrayed as doll-like and passive during the period (fig. 8). While the first section focused primarily on younger children, the works in “Attributes of Girlhood,” including John Singer Sargent’s elegant portrait of 15-year-old Katherine Chase Pratt (1890, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts) posed in front of a wall of hydrangeas, portrayed a range of ages. The inclusion of Charles Courtney Curran’s Lotus Lilies (1888, Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago), in which two women collect eerily large aquatic blooms, revealed how notions of girlhood, female adolescence, and womanhood merged at the time in a troubling, at least to twenty-first century viewers, manner (fig. 9). Thayer’s Angel presided over this section of the exhibition, a visual reminder of the ideals of purity and innocence that unified the nearby paintings of earthbound girls with their flowers, dolls, and pets. The seductive combination of idealism and realism with which the artist portrayed his daughter eloquently revealed just how ardent was his and some of his contemporaries’ desire that girlhood truly be a period of angelic purity.

“Attributes of Girlhood” flowed into “The Innocence of Girlhood,” which was moored by William Merritt Chase’s Idle Hours (ca. 1894, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas) and Winslow Homer’s Girl and Laurel (1879, Detroit Institute of Arts) (fig. 10). The range of media in this section expanded to include sculpture, prints, and photographs, with many of the images suggesting that the natural world was the best breeding ground for girlish innocence. Randolph Rogers’ Daughter Nora as the Infant Psyche (ca. 1871, The Chrysler Museum), a bust-length marble portrait of his little girl emerging from acanthus leaves, provided the most literal depiction of the nineteenth-century conflation of nature, innocence, and femininity (fig. 11). On the rear wall of the gallery, commercial studio photographs of children posed against earthen backdrops suggested just how deeply rooted were the association between childhood innocence and the natural world and the related idea of the naturalness of such innocence (fig. 12). Other works in this part of the gallery made the visitor begin to question the parameters of girlhood innocence, however, by introducing the question of how race affected definitions of girlhood. Myron H. Kimball’s photograph of Emancipated Slaves Brought from Louisiana by Col. Geo. H. Hanks (1863, New-York Historical Society), in which a line of freed slave children stare tensely at the viewer, hung below Ann Hall’s portrait of Louisa and Eliza Macardy (ca. 1845, New-York Historical Society). In the latter, the ivory support accentuates the figures’ light skin as the mother protectively clasps her daughter around the waist.[4] The pairing of these images suggested that to be truly innocent was a privilege dependent on race and class, and was an example of Connor’s thoughtful juxtaposition of works throughout the exhibition.[5] The African-American girl playing a game of dress up in Height of Fashion (1854, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs), a Jean Baptiste Adolphe Lafosse lithograph after Lilly Martin Spencer, alluded to nineteenth-century fears about the potentially corrupting effects of a taste for fashion and ornament, even for those whose means were too limited to indulge in reality.[6]

The viewer passed through a doorway into an adjoining gallery to view the rest of the exhibition, which was laid out in an S-shape. “Mothers, Daughters and Sisters,” the first section in this gallery, explored the family roles that helped to define girls’ identities. For example, Bessie Potter Vonnoh’s sculpture Enthroned (1902, cast 1906, Colby College Museum of Art) and William Merritt Chase’s Mrs. Chase and Cosy (ca. 1895, Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska-Lincoln) offered seemingly timeless images of attentive mothers and loving daughters (fig. 13). In contrast to these iconic representations of familial bliss, Lilly Martin Spencer’s War Spirit at Home (Celebrating the Victory at Vicksburg) (1866, Newark Museum) presented a darker perspective on the nineteenth-century family, one in which contemporary events intrude upon the domestic idyll as a distracted mother reads the newspaper while a baby flails on her lap and her older children march boisterously around the dining room (fig. 14). Spencer’s painting was an ironic response to Training Day (1866, The Old Print Shop), a Currier and Ives print in which the martial spirit is absorbed seamlessly into the domestic realm. The print is discussed in the catalogue, but unfortunately was not included in the exhibition itself (23, 97). “Mothers, Daughters and Sisters” was the smallest section of the exhibition and could have been fruitfully expanded. Seymour Joseph Guy’s A Bedtime Story (1878, Private collection), which was included in the second section, would also have fit comfortably here, speaking as it did to ideals of—and perhaps slight departures from—sisterly duty, as an adolescent girl masterfully frightens her younger siblings with the tale of Goldilocks and the three bears (fig. 15).[7] However, there were a number of works in the exhibition that would have been at home in several sections, which speaks to the rich and varied interpretive possibilities the images in Angels and Tomboys offered.

“Dressing Up ~ Undressing” included formal portraits such as Frank Weston Benson’s Gertrude (1899, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), in which the sitter’s costume signals proper gentility and decorum (fig. 16). Connor used the various states of undress of girls in other works in this section to raise the thorny questions of whether nineteenth-century artists always meant their images of girlhood to appear so innocent, and whether it is possible for twenty-first century viewers to see works of art with nineteenth-century eyes. For example, in Chauncey Bradley Ives’ sculpture The Truant (1871, New-York Historical Society), a schoolgirl’s dress slips revealingly down her shoulder and up her thighs (fig. 17). The work’s title suggests the girl’s mischievous state, while her absorption in listening to a shell—a sign of her affinity with nature—speaks to her innocence. Connor pointed out in the wall text that while the sculpture appears undeniably sensual to modern eyes, “nineteenth-century writers—and by implication viewers—did not consider images of naked children to be provocative or disturbing but rather to capture the innocence and naivety of youth.” She went on to note, however, that the ambivalent readings of Ives’ sculpture echo Henry James’ novella The Turn of the Screw (1898), in which the specter of childhood corruption is raised, but never resolved, wisely letting the visitor decide how to interpret The Truant. Nearby, Seymour Joseph Guy’s Dressing for the Rehearsal (ca. 1890, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC), in which a pubescent nude wearing butterfly wings looks dolefully aside while her body casts a menacing shadow, reminded visitors that given the romantic belief in the innate innocence of childhood, puberty signaled the start of an inevitable, but tragic, fall from grace (fig. 18). Dressing for the Rehearsal was visible through the doorway to the third gallery as you approached Angel in the second, and functioned as a melancholy doppelganger to Thayer’s painting. While Thayer sought to immortalize the state of girlish purity, Guy anxiously alluded to the inevitability of sexual development.

Moving along in the gallery, the mood lightened again with images of “Tomboys and Mischievous Little Girls.” This section featured representations of high-spirited, physically active girls that appeared in art and literature, primarily after the Civil War (fig. 19). Into Mischief, a Currier and Ives lithograph after Louis Maurer (ca. 1857, The Old Print Shop), invites the viewer to chuckle at a grinning little girl who has turned her father’s top hat into a mixing bowl and up-ended her doll in a pitcher, as if gleefully inverting the ideal of easily domesticated girlhood presented in works like McCloskey’s Feeding Dolly. The direct gaze, active pose, and disheveled hair of the rosy-cheeked little girl in John George Brown’s Swinging on the Gate (ca. 1878–79, Taubman Museum of Art) provided an alternate vision to the paintings of girls passively basking in the sun in “The Innocence of Girlhood” section. Brown’s painting and Eastman Johnson’s Winter, Portrait of a Child (1879, Brooklyn Museum), in which his daughter Ethel posed as if taking a break from sledding, visualized the increasingly popular idea that the healthfulness of the nation’s future mothers depended on exercise and fresh air during girlhood. Winslow Homer’s “Winter”—A Skating Scene (Private collection), an 1868 illustration for Harper’s Weekly, ended this section with a reminder that nineteenth-century girls were expected to outgrow their tomboyish ways as they approached womanhood. The wall text pointed out that Homer’s energetic young girls “are contrasted to the older skaters, whose upright poses, tightly braided hair and long skirts that fall to the ice, modestly covering their bodies, indicate their reserved demeanor.” As noted in the exhibition catalogue, very few images of tomboys were truly subversive of nineteenth-century gender roles (90–91).

The tomboy’s relative freedom contrasted with images of “Working Girls” in the next section, revealing how social class inflected representations and experiences of nineteenth-century girlhood (fig. 20). The walls of this and subsequent sections were lavender, the contrast with the sunny yellow of the previous sections effectively signaling a transition to more serious themes. For example, in John George Brown’s Little Servant (ca. 1880, Private collection), a ten-year-old girl takes a break from sweeping in a darkened interior and pulls back a curtain to stare meditatively outside into the sunshine. The inclusion nearby of Jacob Riis’s photographs I Scrubs and Girl and Baby at Doorstep (both ca. 1890, Museum of the City of New York) served as a reminder of the constructed nature of the images on view in this section, as well as in the rest of the exhibition (fig. 21). Like advice literature and fiction, visual representations offered models of girlhood that may or may not have aligned with reality, but certainly influenced how contemporaries thought about real girls. While Riis’s images were intended to spur reform through their doleful presentation of girls too young for the responsibilities they bear, John Lewis Krimmel’s Quilting Frolic (1813, Winterthur Museum), in which a grinning African-American girl blithely holds a tray heavily weighted with china, suggests that such duties fall lightly on small shoulders. And while we are perhaps meant to understand Brown’s servant girl as longing for the freedom that the tomboys in the previous section enjoyed, she appears strong and clean, as if her work is the foundation for a healthful future. Connor pointed out on the wall label that “artists rarely dealt with the grim realities that faced children who had to work for a living,” and only occasionally represented working-class African-American girls.

Winslow Homer’s A Temperance Meeting (Noon Time) (1874, Philadelphia Museum of Art), with its depiction of healthful rural labor and intimation of budding sexuality, transitioned the visitor into the “Adolescence ~ Rite of Passage” section. Like Guy’s Dressing for the Rehearsal, several images in this section visualized the cultural anxiety that attended the idea of female maturity during the nineteenth century (fig. 22). The apprehensive expressions on the faces of the girls in Eastman Johnson’s The Party Dress (The Finishing Touch) (1872, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art) and William Merritt Chase’s Young Girl in Black: The Artist’s Daughter in Mother’s Dress (ca. 1897–98, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution) spoke to the sense of loss that the end of childhood produced and also echoed the ambivalence about growing up that a number of nineteenth-century women vividly recalled in their memoirs (119) (fig. 23). These paintings address the sartorial transitions that were such important and concrete markers of the nineteenth-century girl’s passage to womanhood and that often sparked the memoirists’ ambivalence. Corsets, long skirts, and elaborate hairstyles bespoke greater sophistication, but also literal and symbolic limitations on maturing girls’ activities. While Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ relief portrait of Sarah Redwood Lee (1881, Courtesy of Chesterwood, A National Trust Historic Site, Stockbridge, Massachusetts) presented an adolescent who seemed to be serenely sailing through this transitional phase, other images, including Chase’s portrait and Cecilia Beaux’s Dorothea in the Woods (1897, Whitney Museum of American Art), which hung as pendants, alluded to the moody, psychological disruptions that psychologist G. Stanley Hall and his colleagues had firmly identified with the life stage by the turn-of-the-century (figs. 24 and 25). In Beaux’s portrait of the teenage Dorothea Gilder seated glumly at the base of a tree, the natural world appears neither a source of innocence nor liberation, but instead oddly foreboding.

The final section, “The Young Scholar,” presented paintings and sculptures that addressed expanded educational opportunities for girls. The rise in the number of girls pursuing high school and college degrees as the nineteenth century progressed created new professional opportunities for women, particularly in the areas of writing and teaching. In William Hahn’s Learning the Lesson (Children Playing School) (ca. 1880, The Oakland Museum of California), a girl who stares down at her “pupils” with a serious expression and a switch behind her back seems naturally suited for her future role as an educator. This section addressed the expanded educational opportunities for African-American as well as caucasian girls in the years after the Civil War. While John Rogers’ sculpture Uncle Ned’s School (1866, New-York Historical Society), with its African-American adolescent patiently reading with a middle-aged bootblack offered a hopeful vision, Edward Lamson Henry’s Kept In (1889, Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York), in which a disheveled African-American girl looks disconsolately out a schoolroom window where her classmates play in the sunshine, presented a more ambiguous meditation on post-Reconstruction educational opportunities (fig. 26). By ending with images that addressed female education, the exhibition looked ahead to the gradual expansion of opportunities for women in American society during the following century.

The exhibition extended into the museum at large through a series of object labels in the permanent collection galleries that connected works such as a Bridal Ensemble Worn by Ntombiyise Mandwandwe Shiza, a Zulu woman from South Africa, (1960s, Newark Museum) with themes addressed in the Angels and Tomboys exhibition. This intervention by intern Ellen Crosier was an effective means of positioning the exhibition’s nineteenth-century American art in a broader historical context.

The exhibition was accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue, which includes five thematic essays that address some of the works included in the exhibition in depth while introducing additional images to broaden the discussion. In the opening essay, “The Flowering of Girlhood Narratives, 1850-1870,” Holly Pyne Connor adeptly traces the rise of girlhood as a subject among American artists, crediting Lilly Martin Spencer with creating “the earliest narrative images focusing solely on American girlhood” in the 1850s (13). Over the next two decades, male painters, including Seymour Joseph Guy, Eastman Johnson, Winslow Homer, and Thomas Eakins, also embraced narrative paintings of girls, a subject already popular in European art. Connor explains that artists like Spencer and Johnson used girlhood to explore serious social issues related to the aftermath of the Civil War, while Homer seems to have “viewed girlhood as a minor subject” (25). Regardless of how light or weighty were artists’ approaches, by the 1880s “girlhood had become an established subject in American art” (25).

In the second essay, “Angel Children: Defining Nineteenth-Century Girlhood,” Connor discusses the practice of representing young “children as asexual, angelic beings” and details the shift from Calvinist ideas of the innate sinfulness of children to the romantic model of childhood innocence sparked by John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau during the Enlightenment (31). The remainder of the essay analyzes many of the paintings included in the first two sections of the exhibition, laying out in greater depth than possible in the galleries the use of poses, settings, and especially attributes to differentiate and define gender over the course of the nineteenth century.

Barbara Dayer Gallati explores “the iconography of girlhood as it may have been inflected by familial relationships between various artists and the children they painted” in the third essay, “Family Matters: Artists and Their Model Girls” (57). She begins with a subtle reading of Spencer’s War Spirit at Home (Celebrating the Victory at Vicksburg (1866, Newark Museum) in light of the challenges the painter faced in balancing her roles as artist and mother, and moves on to consider how the personal losses or fatherly anxieties of male painters, including Eakins, Chase, and Abbott Handerson Thayer, may have affected depictions of the girls in their families. Gallati’s essay also reveals the variability in motivation when artists used sisters and daughters as models. For example, Eakins chose to display only one of the moody domestic scenes he painted of his sisters and extended family members, while Chase built his reputation in part on the public display of imagery that spoke to the interconnectedness of art and family life.

Sarah Burns tackles less than angelic images of girlhood in her essay “Making Mischief: Tomboys Acting Up and Out of Bounds.” She argues that while few images of tomboys challenge gender boundaries in a truly disruptive manner, Spencer’s pictures of mischievous girls, such as Fruit of Temptation (1857, Courtesy of the Ohio Historical Society), are an exception. The humorous and open-ended nature of Spencer’s imagery allowed the artist to craftily celebrate subversive behavior without overtly challenging accepted ideals of proper decorum. Burns believes that some of the illustrations accompanying moralizing verses aimed at girls were similarly destabilizing, “allow[ing] greater interpretive latitude” than the verses themselves (97). This raises the frustratingly hard-to-answer question of how everyday nineteenth-century viewers, particularly girls, interpreted such imagery, but Burns argues that images of less than angelic girls ultimately offered “loopholes, or knotholes, through which beholders, not least little girls, might glimpse new and powerful roles for women” (103).

In her essay “Roses in Bloom: American Images of Adolescent Girlhood,” Lauren Lessing “examines images that both reflected and transformed American conceptions of adolescent girlhood over the course of the nineteenth century,” providing a thoughtful overview of visual representations of teenage girls during the period (108). Lessing discusses how artists, including Johnson, Chase, and Guy, explored the physical, mental, and social changes associated with female adolescence. She argues that artists like Erastus Dow Palmer and John Mix Stanley “presented adolescence as a period during which girls might alter their identities – shifting definitions of class and race in the process” (115). Whether this state of flux was viewed as a positive or negative depended, of course, on the race of the subject. Meanwhile, images of country girls countered and reflected deep-seated social anxieties about the corrupting effects of urbanization and modernity on young bodies and fears of the decline of the “American race.”

The catalogue’s exhibition checklist included the page number on which each work was illustrated, and the index referenced the names of scholars cited in the text as well as artists and subject entries. Both aspects will be helpful for scholars using the catalogue for research purposes. Several works included in the exhibition checklist were not on display in Newark. Samplers by Julia Ann Morris and Elizabeth Stone, from the Newark Museum’s collection, were shown at the other two venues, and Mary Cassatt’s The Reader (1877, Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art) was only exhibited at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Vanity (1899, Newark Museum), a work initially attributed to John George Brown, but recently re-classified as a copy in the style of Brown by scholar Martha Hoppin, was not displayed at any of the museums.

The exhibition and catalogue make important contributions to American art history as well as childhood studies. Of course, there are always additional works that one would like to have seen included. There was only one Sargent painting, and it would have been wonderful to have Mary Cassatt’s thoughtful explorations of girlhood and female adolescence more fully represented. However, Barbara Dayer Gallatti’s exhibition Great Expectations: John Singer Sargent Painting Children richly explored the painter’s depictions of childhood, and Sargent’s and Cassatt’s expatriate status perhaps argued against a fuller inclusion of their work in this case. The exhibition primarily focused on artists working in the realm of the fine arts, and an examination of a broader swath of visual culture would have led to potentially different understandings of girlhood. For example, apart from physical caricaturing in Krimmel’s Quilting Frolic, the representations of African-American girls in the exhibition were largely sympathetic, and in that respect a far cry from some of the dehumanizing illustrations and advertisements of the period.[8] Those are minor qualms, however, for the exhibition was wonderfully successful in demonstrating the visual and cultural richness of nineteenth-century American images of girlhood and in “pav[ing] the way for future, more in-depth investigations” of the subject (7). Seymour Joseph Guy’s images of girlhood, for example, would make for a fascinating exhibition in their own right.[9] More work could certainly also be done on the tomboy. Literary scholar Michelle Ann Abate has argued that the figure of the tomboy “is an unstable and dynamic one, changing with the political, social and economic events of its historical era,” which raises the question of how visual representations of tomboys and mischievous girls may have evolved from the 1850s through the end of the century.[10] Sarah Burns begins to explore the issue in her catalogue essay, providing a foundation for future research. And how did American images of girlhood align with, and depart from, those being painted in England and France during the second half of the nineteenth century?[11] What insights into American ideas about girlhood might be gained from a cross-cultural comparison? Prompting the viewer to ask additional questions about the subject being explored is surely a sign of a successful exhibition.

Gretchen Sinnett

Salem State University

gsinnett[at]salemstate.edu

My thanks to Curator Holly Pyne Connor for graciously giving me a tour of the exhibition and answering my subsequent questions.

[1] Other recent exhibitions with scholarly catalogues that explored the visual and material cultures of childhood include Barbara Dayer Gallati, Great Expectations: John Singer Sargent Painting Children (Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum in association with Bulfinch Press, 2004); Claire Perry, Young America: Childhood in 19th-Century Art and Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University, 2006); and Juliet Kinchin and Aidan O’Connor, Century of the Child: Growing by Design, 1900–2000 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012).

[2] See Martha Banta, Imaging American Women: Idea and Ideals in Cultural History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987) and Bailey Van Hook, Angels of Art: Women and Art in American Society, 1876–1914 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996) for wide-ranging discussions of American images of women in the nineteenth century.

[3] It is ironic that the frame was designed by Stanford White, whose seduction of the adolescent Evelyn Nesbit later led her unstable husband to murder the architect.

[4] These images are not discussed in the Angels and Tomboys catalogue. For a brief discussion of the Macardy portrait, see Marie-Stephanie Delamaire, “Louisa and Eliza Macardy, ca. 1845,” in Richard Brilliant, Group Dynamics: Family Portraits and Scenes of Everyday Life at the New-York Historical Society (New York: The New-York Historical Society, 2006), 124–25; and for the Kimball photograph, see Mary Niall Mitchell, “‘Rosebloom and Pure White,’ or So It Seemed,” American Quarterly 54 (September 2002), 369–410.

[5] For an important exploration of nineteenth-century discourses about childhood innocence and race, see Robin Bernstein, Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights (New York: New York University Press, 2011).

[6] This image is not discussed in the Angels and Tomboys catalogue. For a discussion of the image as “a visual joke about African-Americans’ supposed love of finery,” see Claire Perry, Young America: Childhood in 19th-Century Art and Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University, 2006), 82–83.

[7] For a discussion of depictions of female adolescents in light of late nineteenth-century discourses about proper family relationships, see my dissertation “Envisioning Female Adolescence: Rites of Passage in Late Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century American Painting” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2006), especially 22–26, 34–36, 190–234.

[8] For an examination of some of this imagery, see Carolyn Dean, “Boys and Girls and ‘Boys’: Popular Depictions of African-American Children and Childlike Adults in the United States, 1850-1930,” Journal of American & Comparative Cultures 23:3 (2000), 17–35.

[9] The most recent examinations of Guy are Lauren Lessing, “Rereading Seymour Joseph Guy’s Making a Train,” American Art 25:1 (Spring 2011), 96–111; and Bruce Weber, “Seymour Joseph Guy: ‘Little Master’ of American Genre Painting,” The Magazine Antiques 174:5 (November 2008), 140–49.

[10] Michelle Ann Abate, Tomboys: A Literary and Cultural History (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008), xii.

[11] Important explorations of images of children in nineteenth-century European art include Marilyn R. Brown, ed., Picturing Children: Constructions of Childhood Between Rousseau and Freud (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2002); Anna Green, French Paintings of Childhood and Adolescence, 1848–1886 (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2007); and Greg M. Thomas, Impressionist Children: Childhood, Family, and Modern Identity in French Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011).