The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Introduction

In 1882, Antonios Alexandrides (1837–1912), an artist who had returned to his native Ottoman-ruled Crete after having studied at the Academy of Vienna (1860–64), offered a painting as a present to the new Metropolitan Bishop of Crete, Timotheos Kastrinoyiannakis (fig. 1).[1] The painting, a religious allegory, showed the resurrected Christ, enthroned above the tomb from which he has risen, around which a crowd gestures in despair. Directly below the tomb, a widow-like figure clad in black, hand on a carriage of lilies, sits despondently. In the foreground, a young defeated soldier has collapsed in the arms of a mother-figure, still holding on to his broken sword with one hand and clasping the staff with the withered Greek flag, half-covering a canon, with the other. An inscription on the open sarcophagus reads in Greek: “All ye who pass by, behold and see if there be any sorrow, like unto my sorrow,” quoting Jeremiah (Lamentations 1:12), who is represented on the right side of the sarcophagus.[2]

There could be no mistake at the time about the meaning of the painting. The resurrection of Christ and the Greek flag signified the ongoing struggle of the Cretans in the name of faith and country for the island’s union with the motherland, Greece. Τhe destruction of Jerusalem alluded to by the verses of Jeremiah’s Lamentations was a certain reminder of the Fall of Constantinople but also a reference to the reality of the equally “fallen” and suffering island of Crete. The meaningful triple parallel of the fallen Jerusalem, Constantinople, and Crete, was underscored by the representation of the widow-like figure sitting in abandonment, solitary and in grief, in the foreground, just as described in the opening verses of Lamentations (1:1–2): “How doth the city sit solitary, that was full of people! How is she become as a widow! She that was great among the nations and a princess among the provinces, how is she become tributary! She weepeth sore in the night and her tears are on her cheeks.”

The Sanctuary Screen Paintings at the Monastery of Epanosifi

In exactly the same year, 1882, when he donated the Resurrection painting to the Metropolitan Bishop of Crete, Alexandrides completed his share of work for the church of the monastery of Epanosifi. He had been working for the church of the monastery, together with Ioannis Stavrakis (1841–1909),[3] an artist who had also recently returned to Crete after having completed his studies at the School of the Arts in Athens.[4]

Situated in the center of the municipality of Heraklion, the monastery of Epanosifi was founded in the first decades of the seventeenth century under Venetian rule. It retained an exceptional place in the reverence of the Christian laity at the time of the long Ottoman rule that followed.[5] Flourishing toward the end of the eighteenth century, the monastery is recorded as subsequently suffering from great damage both during the revolution of 1821 and from a severe earthquake in 1856. Its central double-naved church, the Church of St. George and the Transfiguration, was thus rebuilt by special permission in 1862,[6] but was only decorated twenty years later.[7] The contract for the paintings for the church’s sanctuary screens (fig. 2), found recently in the municipal archives of Heraklion,[8] shows that it came from the Council of Elders, presided over by the Metropolitan Bishop of Crete Meletios Kavasilas, acting as representatives of the monastery.[9] It was signed in 1880, and the works assigned were completed by June 1882.[10]

The contract for the sanctuary screens’ paintings contains a detailed description of the iconographic program,[11] and it specifies the length of time in which the work was to be completed, the payment terms, the residence of the artists while at work, and even the manner of transportation of the works from the artists’ workshops, after their completion.[12] Among the various demands made by the commissioning body, two clauses deserve special attention: the sixth clause clearly states that the artists had to adhere to “the type (typos) accepted by the Eastern Orthodox Church,” and the eighth clause specifies that their completed work was to be examined by specialists (eidēmones) and, if found unacceptable or lacking in any way, the artists would be called back to make the necessary changes.[13] In other words, the artists were obliged by the contract to adhere not only to a given iconographic program, but also to specific stylistic requirements.

As indicated by the series of payment documents (a series of handwritten notes written by the Metropolitan Bishop of Crete ordering the bank to make payments to the artists for specific works already delivered, notations by the bank that it had made payment, and the receipts for the payments written and signed by the two artists),[14] the works were executed between 1880 and 1882 and paid for at delivery in the given time span of one and a half years, exactly as agreed. As no changes were demanded, we may surmise that the works were approved by the specialists and, thus, were thought to conform to “the type (typos) accepted by the Eastern Orthodox Church.”

In the context of the contract specifications, it comes as somewhat of a surprise that the works by the two artists, present today on the sanctuary screens of the central church of the monastery, are clearly western in style and iconography.[15] Executed in oils, they are largely based on nineteenth-century Western European prototypes. More specifically, the two artists extensively used as models Nazarene engravings, especially from Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld’s Bibel in Bildern (1860). In addition, they used Gustave Doré’s Illustrated Bible (1866), and Old Master paintings, such as Raphael’s St. Michael Slaying the Dragon (Musée du Louvre, Paris), the same artist’s Transfiguration (The Vatican Museums, Rome), and Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper (Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan), all widely known in Greece at the time from contemporary engravings.[16] Indeed, the Epanosifi paintings stand out today as the first known use of these artistic sources to be accepted by the church authorities of Crete during the Ottoman rule.[17] They represent the official adoption by the Cretan church of what is known as “improved Byzantine art,” which had been programmatically promoted by the free neo-Hellenic state and its autocephalous Church since the 1840s.[18]

The “Improvement of Byzantine Art”[19]

The “improvement of Byzantine art” was introduced programmatically in the neo-Hellenic state during the rule of the Bavarian King Otto. Its Greek spokesmen presented it as primarily an aesthetic improvement, growing from the need for post-Byzantine icon painting “to be purged of all its defects.”[20] They advocated the introduction of perspective and chiaroscuro and, in general, the application of what were deemed "scientific rules” to icon painting, and they often made debasing comments on what they considered at the time to be the defects of Byzantine style icon painting.[21] In short, they in fact proposed a Byzantine art divested of almost every one of its central characteristics.[22]

This was the time when the Bavarian program for the rebirth of the golden age of Pericles revived interest in classical Greece, while concurrently the spirited call of the Megali Idea kindled irredentist hopes.[23] The proponents of improvement tried to reconcile irredentism and the ideology of the revival of classical Greece in their argumentation, but references to Constantinople and the Byzantine past of Greece always remained uneasy.[24] They may have praised “the glorious works of Christian Greece,” the study of which was deemed “of grave national importance,”[25] but they in fact undermined the role of the art of the Byzantine era by suggesting to Greek artists that they copy Western Christian art works. More specifically, they argued that just as ancient Greece had been the wellspring of Western art, the imitation of Western art prototypes was to be considered as a payback to the modern Hellenes.[26]

Among the sources they promoted and prototypes they proposed as exemplary were first and foremost the works executed in Athens by artists belonging to the Nazarene circle.[27] The work at the Russian church of Athens, Soteiras Lykodimou, by Ludwig Thiersch, who was also appointed professor at the School of Arts in Athens, was praised as a supreme example of the new “Hellenic Christian art.”[28] So, too, Alexander Maximilian Seitz’s work at the grand cathedral Church of the Annunciation in Athens soon became exemplary of the revival of icon painting in the modernized and Europeanized neo-Hellenic state.[29]

As the century progressed, and after King Otto’s expulsion (1862),[30] the proposed improvement of Byzantine art came to rely on a variety of other sources. Beyond Nazarene art and the long-favored Old Masters (especially Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Guido Reni, and Peter-Paul Rubens), the list of sources came to include Doré’s Bible illustrations and later the illustrations of Alexandre Bida, Heinrich Hofmann, Bernhard Plockhorst, as well as the paintings of Antonio Ciseri, all of which were copied by Greek artists in Greek orthodox churches well into the twentieth century.[31]

The few who voiced their opposition to these sources and to the uncritical adoption of the prototypes proposed, pointing out that they were foreign both to national identity and to Greek orthodox dogma, were instantly dubbed “retrogressives.”[32] They were ignored by the official authorities of the state, the state run School of the Arts, and the autocephalous Church of Greece, and the argumentation for the necessity for the improvement of Byzantine art prevailed. Yet, despite the presentation of the proposed sources as primarily effecting a formal and stylistic (aesthetic) improvement, allowing the “spiritual content of icons to remain unaffected,”[33] the engravings and artworks proposed and disseminated as models were more than stylistic prototypes. Closely connected to the Bavarian efforts to “recreate, or invent, a Byzantium that linked German culture with Classical Greece and the East,”[34] Nazarene art had been programmatically introduced in Greece during Otto’s reign.[35] But even beyond Nazarene art and the Bavarian program, the dissemination in Greece of other Christian artworks is safely known today to have been related to Great Power geopolitical strategies in the face of the Eastern Question.[36]

The Cretan Question, Improved Byzantine Art, and the Sanctuary Screen Icons of the Monastery of Epanosifi

Cretans were well acquainted with Great Power geopolitical strategies in the East.[37] Engaged in an ongoing dual struggle for their freedom from Ottoman rule and for their union with Greece, Cretans frequently called on the Great Powers as they were “thinking on their strategies on the Eastern Question,” to consider Crete’s union with Greece.[38] While so doing, Cretans persistently underlined the religious character of their struggle. In their addresses to the Great Powers they referred to the “holy war of the Christian people of Crete,” and sent protests to the nations of “the Great Christian Powers” appealing to their philhellenic sentiment and noting in bitterness that the state officials of their countries had embarked οn an “anti-crusade.”[39]

The Cretan Church was faced with a dilemma. The political and constitutional union of Crete with Greece entailed the prospect of the union of the Cretan Church with the autocephalous Church of Greece. This meant an open breach with the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, to which the Cretan Church was subject, as were all Orthodox Christian Churches in the Ottoman-ruled territories.[40] Nevertheless, many among the prelates of the Cretan Church, in promoting the Cretan cause, openly supported and even actively participated in unionist and rebellious activity.[41]

Interestingly however, this support is also reflected in official ecclesiastical painting, and what is even more interesting is that the Cretan Church chose to promote the claim for Crete’s union with Greece by adopting the art of the “Great Christian Powers.” Thus, the Council of Elders and the Metropolitan Bishop assigned to Alexandrides and Stavrakis, for the sanctuary screens of the main church of the Epanosifi monastery, an iconographic program that addressed key issues connected to the Cretan cause, and they carefully selected improved Byzantine art prototypes to serve this purpose.

Evident at first glance is the fact that the iconographic programs of the two sanctuary screens of the church at Epanosifi are differentiated by a main distinguishing feature: the sanctuary screen of the Transfiguration nave includes numerous compositions based on the Old Testament, whereas the sanctuary screen of the nave of St. George includes compositions exclusively based on the New Testament.[42] Thus, while a free adaptation of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper is found on the gable of the St. George sanctuary screen, the gable of the Transfiguration screen shows Moses Receiving the Tablets of Law (a faithful copy of Carolsfeld’s composition). Similarly, the compositions of Jeremiah’s Lamentation, The Vision of Ezekiel, Isaiah’s Prophesy, Daniel in the Lions’ Den and Jonah Cast Forth by the Whale (based on Carolsfeld’s and Doré’s engravings) in the lower zone of this screen (figs. 3, 4, 5), are juxtaposed with the New Testament scenes of Christ Washing the Disciples’ Feet, Christ on the Mount of Olives, Peter’s Denial, and the Seventh Station of the Cross (all based on various Nazarene engravings) in the St. George screen.

Beyond this important distinction, the two screens are differentiated in another way: the main icons or despotikes (for example, fig. 6) on the sanctuary screen of St. George are direct copies of Alexander Maximilian Seitz’s (1811–88) work at the cathedral church of Athens, the Church of the Annunciation.[43] The copies of Seitz’s Athenian icons related the sanctuary screen of St. George to Athens, and additionally brought to mind the grand celebration and festivities held at the cathedral of Athens on the 25th of March, the date celebrating both the Annunciation and the national freedom from the Ottoman rule, a freedom Crete still waited to share.[44] The Athenian connection of the screen of St. George was underlined in yet another way. In Crete, it had become common practice by the 1880s to remember King George, the king of the Hellenes who reigned at the time (1863 -1913), during the feast day of St. George.[45] And this was most probably also done during the celebration of the feast day of St. George at the monastery of Epanosifi.

In contrast to the Athenian emphasis of the screen dedicated to St. George, there are a number of references to Crete in various icons on the sanctuary screen of the Transfiguration: Apostle Titus (founder of the Cretan Church), Bishop Myron (Bishop of Crete), The Ten Martyrs of Crete, and Apostle Paul Preaching in Crete all suggest that the Transfiguration screen addresses a Cretan identity. Such an interpretation is strengthened by inscriptions included in two icons. Jeremiah’s Lamentation (fig. 7), a faithful copy of Carolsfeld’s engraving of the subject, includes the inscription of the verse (1:1–2) illustrated by the Nazarene artist (“How doth the city sit solitary”; see Introduction).[46] For the Christian laity of the period, the reference in the Greek inscription to Polis (city; see detail fig. 8), must have instantly brought to mind the Fall of Constantinople (Polis, in Greece still refers to Constantinople today.) and the end of the glorious days of the center of Christendom now awaiting “redemption” exactly as Crete was. In other words, as in the painting offered by Alexandrides to the Metropolitan Bishop of Crete in 1882 (see Introduction) the icon and its inscription allude to the triple parallel of the fallen Jerusalem, Constantinople, and Crete.

Directly above Jeremiah’s Lamentation is the composition of The Ten Martyrs of Crete (fig. 9).[47] Based on a free adaptation of Carolsfeld’s engraving of Christ Sending Out the Twelve Apostles, it includes two inscriptions. The lower one refers to their martyrdom and death under Roman Emperor Decius, while directly above it, on a plaque with a sword placed upon it, another inscription reads: “Fight for Faith and Motherland” (fig. 10). It is the famous line from Alexander Ypsilantis’s call for revolt against the Ottoman occupation of Greece in 1821[48] and undoubtedly was understood as a call to the Christian Cretans to continue the “unfairly on-going Greek War of Independence.”[49] Depictions of the Ten Martyrs of Crete bearing the same inscription had acquired a central place in the imagery of the Cretan struggle against the tyranny of the Ottomans during this period, leaving no doubt as to the reason for the inclusion of this icon on the sanctuary screen with the Cretan identity.[50]

Another well-understood image, bearer of an explicit message for the Christian populace of Crete, was the icon of the Three Hierarchs, included in the middle zone of the Transfiguration sanctuary screen. The feast-day of the Three Hierarchs (Church Fathers of the Eastern Orthodox Church and Ecumenical Teachers) had become an established celebration for newly founded schools all over the island.[51] During these celebrations speeches were given stressing the symbolic significance of the Hierarchs for Hellenism and Greek learning while also underlining the role of education to promote the Cretan cause.[52] Thus, the combined compositions of Jeremiah’s Lamentation, The Ten Martyrs of Crete and The Three Hierarchs must have been clearly understood as a message of continued revolution in the name of Faith and Country for the unredeemed island of Crete, be it by the sword or by pen.

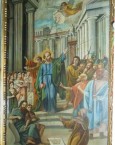

The inclusion in this sanctuary screen of the icon of The Apostle Paul Preaching in Crete, found today at the far end of the central middle zone (fig. 11) is interesting in many ways. Based on a free adaptation of Carolsfeld’s engraving of The Apostle Paul Preaching in Athens, the scene is unusual because Paul had never preached in Crete, but instead instructed his disciple Titus to remain on the island to spread Christianity and found the Cretan apostolic church.[53] Moreover, in his Epistle to Titus Paul had made disturbing references to Crete and the Cretans. The Apostle had quoted Epimenides’s denunciation, when warning Titus that: “Cretans are always liars, evil brutes, lazy gluttons” (Titus 1:12).[54] He had noted their easily aroused rebellious spirit and their independent nature (Titus 3:1). So, though the scene of Paul Preaching in Crete may be interpreted as a reference to the appointment of Titus, who is commemorated on the sanctuary doors together with the Bishop Myron (fig. 12), it is also possible that it was to establish a symbolic relationship between the Greek and the Cretan Church, as Pauline and Apostolic.[55]

Among the icons of this screen, the Old Testament scene of Moses Receiving the Tablets of the Law (fig. 13), in the gable, stands out. Indeed, the unusual presence of Moses Receiving the Tablets of the Law as a key composition in this particular screen indicates its importance.[56] The story of Moses, leader of the people of Israel during the Exodus, had been a well-established metaphor for the Christian Cretans and their ongoing struggle for Crete’s freedom from Ottoman domination and the island’s union with Greece. Indicative of this is the address of the Metropolitan Bishop of Crete Timotheos Kastrinoyiannakis, who on the occasion of his enthronement in 1882 said: “As once was Moses, so am I called today, to lead you in your exodus from Egypt.” He closed his speech by expressing this wish: “And may you be the new people of Israel always heeding Moses’s voice so that you may finally enter the Promised Land.”[57] Equally well understood as a reference to Crete’s ongoing struggle, was the theme of the God-given laws alluded to by the composition of Moses Receiving the Tablets of the Law. As noted in a number of contemporary sources, Crete had been the birthplace of laws, since, according to Plato, King Minos had received laws directly from Zeus allowing him to rule effectively and peacefully. Greece and the West owed their laws to Crete, yet despite this heritage the island was unjustly and unlawfully ruled by the Ottomans.[58] In other words, the Old Testament composition of Moses Receiving the Tablets of the Law alluded to the fact that the Great Powers owed to Crete the laws by which they were governed, and also invited a comparison of the Cretans with the ancient people of Israel who had also been banned from their motherland.

A frequent term in the Cretan discourse about Crete’s union with Greece was the word “resurrection.”[59] A well-established symbol for this resurrection, often also used in history painting of the Greek War of Independence, was the Resurrection of Christ.[60] At Epanosifi, the Resurrection crowns the gable of the Transfiguration screen (fig. 14). Moreover, since the Transfiguration of Christ is a preview and an anticipation of his resurrection, the whole screen could be read metaphorically as the anticipated resurrection of Crete.[61]

The panel of the Resurrection is juxtaposed with the Crucifixion of Christ, which crowns the screen dedicated to St. George (fig. 15), further elucidating the distinction between the two screens: anticipated redemption for the Transfiguration (Cretan) screen and the fulfilled deliverance of Athens and the Greek state for the Georgian screen. The redemptive message of the overall iconographic program, in which politics and religion are engaged in a constant dialogue, may, thus, also be interpreted as entailing an interplay between the terms Lytrosis (redemption) and Alytrotismos (unredeemed).[62] Analogously, in keeping with Eastern Orthodox typological interpretations, the two screens, read together, may be considered as presenting the Economy of Salvation, whereby Crete is metaphorically presented as anticipating redemption, while Athens or, in broader terms, the Greek state, is presented as already redeemed. While in the Transfiguration screen redemption is promised, prefigured, and foretold, in the screen of St. George it is completed and fulfilled.[63]

It is evident, then, that at the heart of the iconographic program of the two sanctuary screens lay the Cretan claim for the island’s union with Greece. And this now explains why in 1882 Alexandrides chose to offer to the newly appointed Metropolitan Bishop of Crete a religious allegory showing the Resurrected Christ and the withered Greek flag.

In conclusion, this case-study of the Epanosifi sanctuary screens sheds new light on the introduction of improved Byzantine art in ecclesiastical painting. It demonstrates that improvement was used by the Church of Crete for the promotion of the Cretan cause. More specifically, it is clear that the adoption of the new style was intended to align Cretan ecclesiastical painting with neo-Hellenic ecclesiastical painting, in an attempt to visually express the claim for the union of Crete with the motherland. At the same time, the Cretan claim is also shown in the iconography of the panels, which was carefully planned to express notions of union, redemption, and resurrection, which all were terms of the unionist agenda. The Epanosifi works thus illuminate the hitherto unacknowledged role played by ecclesiastical art in the long Cretan struggle for the island’s union with Greece that was finally realized on December 1, 1913.[64]

General Plan and Iconographic Program of the Sanctuary Screens

According to the Contract (1880)

The Sanctuary Screen Dedicated to St. George (South)

1 Christ on the Cross

2 The Virgin Mary

3 The Weeping Women at the Tomb

4 John

5 Longinus

6 Busts of 21 Prophets (placed around the gable as indicatively

shown by the three circles)

7 The Last Supper

8 (dodekaorton) a/ The Birth of John the Baptist, b/ The Birth

of the Virgin, c/ the Presentation of the Virgin, d/ The Annunciation,

e/ The Nativity, f/ The Presentation οf Christ at the

Temple, g/ The Baptism, h/ The Road to Calvary, i/ The Crucifixion,

j/ The Resurrection, k/ Doubting Thomas, l/ The Ascension,

m/ The Pentecost

9 The Decapitation of St. George

10 The Madonna Enthroned

11 Christ Enthroned

12 St. John the Baptist

13 Christ Washing the Feet of the Disciples

14 Christ Praying at the Mount of Olives

15 Apostle Peter

16 Apostle Paul

17 Peter’s Denial

18 Station of the Cross

The Sanctuary Screen Dedicated to the Transfiguration (North)

1 The Resurrection

2 The Myrrbearers

3 Mary at the Tomb

4 Moses receiving the Tablets of the Law

5 Busts of 21 Prophets (placed around the gable as indicatively

shown by the three circles)

6 (dodekaorton): a/ The Samaritan Woman, b/ The Pool of Bethesda,

c/ The Raising of Lazarus, d/ The Entry into Jerusalem, e/

The Decapitation of John the Baptist, f/ The Healing of the

Blind Man, g/ The Myrrbearers, h/ The Healing of the Paralytic,

i/ The First Ecumenical Council at Nicaea, j/ All Saints,

k/ Mid-Pentecost, l/ Paul of Thebes, Savvas, and Euthymios,

m/ Sts. Nicholas, Charalambos, and Athanasios.

7 The Archangel Michael

8 Apostle Paul Preaching in Crete

9 The Death of the Virgin

10 The Transfiguration

11 The Three Hierarchs

12 The Ten Martyrs of Crete

13 Jeremiah’s Lamentation

14 The Vision of Ezekiel

15 The Bishop Myron

16 Apostle Titus

17 Isaiah’s Prophesy

18 Daniel in the Lions’ Den

19 Jonah Cast Forth by the Whale

NOTE: The iconographic program given in written form in the contract follows the Eastern Orthodox theological significance of the icons commissioned. It provides specifics only on which screen and in which zone the icons were to be placed. This does not allow certainty today regarding the exact original order of the placement of those icons which are either uncommon or, if common, not always found in a specific place and in a specific order on sanctuary screens of the same period. In the case of the Epanosifi sanctuary screens, questionable is the order of placement of: no. 8 The Apostle Paul Preaching in Crete, no. 11 The Three Hierarchs, and no. 12 The Ten Martyrs of Crete (three main icons on the Transfiguration sanctuary screen) and no. 13 Jeremiah’s Lamentation, no. 14 The Vision of Ezekiel, no. 17 Isaiah’s Prophesy, no. 18 Daniel in the Lions’ Den, and no. 19 Jonah Cast Forth by the Whale (the five lower zone compositions on the Transfiguration sanctuary screen).

I would like to thank the reviewer Jeanne-Marie Musto for her important recommendations and the editors Petra ten Doesschate Chu and Robert Alvin Adler for all their helpful suggestions and insightful observations which greatly improved the final version of this paper.

All translations by the author unless otherwise indicated.

[1] Referred to in an editor’s note as “a painting showing Christ amidst a sorrowful crowd,” in the newspaper Minos (Heraklion), December 4, 1882, 2. Timotheos Kastrinoyiannakis was enthroned on September 22, 1882 and was the last Metropolitan Bishop of Ottoman-ruled Crete. During this period of Ottoman rule (1645–1898) the Metropolitan Bishop of Crete was elected by the Ecumenical Patriarchate to which the Cretan Church was subject, until Act 276/1900, when the Church of Crete became semi-autonomous (self-governed, but under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate), which it remained until after Crete’s Union with Greece in 1913. For permission to photograph the painting and publish the image, gratitude is owed to His Eminence Archbishop of Crete Irinaios and to His Eminence Metropolitan of Rethymnon and Avlopotamos Evghenios.

[2] “PANTES OI PARAPOREVOMENOI ODON, EPISTREPSATE KAI IDETE EI ESTIN ALGOS KATA TO ALGOS MOU.” English trans., The Holy Bible, King James version. In the background a priest-like figure seems to be represented under an arch of a building which is also faintly discernible. However, heavy varnish layers do not allow clarity, and deter interpretation.

[3] For the two artists, their professional activity in Crete and their work at the Epanosifi Monastery see Denise-Chloe Alevizou, “Archeiakes martyries ghia tēn epagelmatikē drastēriotēta tōn zōgraphōn Antōniou Alexandridē kai Iōannē Stavrakē kai ē koinē anathesē ghia to katholiko tēs I. Monēs Epanōsēphē (1880–1882)” [Archival evidence on the professional activity of the artists Antonios Alexandrides and Ioannis Stavrakis and the joint commission for the church of the Epanosifi Monastery (1880–1882)], Cretica Chronica 32 (2012): 155–230.

[4] For a full account of the history of the School of the Arts in Athens (Polytechnic School), at the period, see Antonia Mertyri, Ē Kallitechnikē ekpaidephsē tōn neōn stēn Ellada [Artistic education of the youth in Greece (1836–1945)] (Athens: NSC-NIR, 2000).

[5] For the history of the monastery see Emmanouil Petrakis, “O Aghios Geōrghios Apanōsēphēs (Ē istoria mias Monēs)” [St. George Apanosifis (The history of a monastery)], Cretica Chronica 10 (1956), 29–100.

[6] At that time, special permission from the Sublime Porte (a common contemporary metonym for the Ottoman government) was necessary for the rebuilding of Christian orthodox churches in Ottoman-ruled Crete. For the specific permission see Petrakis, “O Aghios Geōrghios,” 81.

[7] See Petrakis, “O Aghios Geōrghios,” 83–84. As noted in this study, the monastery had been completely destroyed again in 1866 “from the menace of the Turks” following which it was deserted by its head and monks, from fear of further Ottoman attacks. However, as also noted, it had served as a secret meeting place of revolutionaries during the ensuing revolution of 1877, which indicates that it must have been rebuilt again after 1866 but left undecorated until 1882, when we know that Alexandrides and Stavrakis completed the works assigned for the sanctuary screens.

[8] The 1880 contract is a manuscript comprised of 3 folios found today at the Department of the Historical Archives, Municipal Library of Heraklion, archive ref. no. 2 157-214/215/ 216. The full text of the contract is transcribed in Alevizou, “Archeiakes martyries,” 161–66.

[9] In accordance with the 1870 Constitution of the Patriarchal and Parish Monasteries of Crete, a charter in effect until 1900, the Council of Elders was designated as the supervising authority of the Monasteries and was presided over by the Metropolitan Bishop of Crete. At the period, the Metropolitan Bishop of Crete was Meletios Kavasilas, known as “the Kalymnian,” due to his origins from the isle of the Dodecanese Kalymnos (terms of office: 1868 - 1874 and 1877 – 1882). After his death in August 1882 he was succeeded by Timotheos Kastrinoyiannakis (see note 1).

[10] For the completion of the works by June 1882, see Alevizou, “Archeiakes martyries,” 161–66, 169–70. For permission to photograph and publish images of the works, gratitude is owed to His Eminence Archbishop of Crete Irinaios and to the head of the monastery, the Very Rev. Archimandrite Bartholomew.

[11] A General Plan and Iconographic Program of the Sanctuary Screens According to the Contract (1880) is provided here in order to help the reader. The iconographic program shown is based on the information given in text in the contract. The plan shows the works executed by the two artists as they appear on the two sanctuary screens today.

[12] The icons of the sanctuary screens were portable icons, usually executed in the artists’ workshops, and intended to be fitted in their designated place (according to the iconographic program), on the sanctuary screens after their completion.

[13] See the relevant passages of the contract in the Greek text in Alevizou, “Archeiakes martyries,” 165–67 on the otherwise unspecified reference in the contract to “specialists,” (eidēmones).

[14] For the payment documents found at the Department of the Historical Archives, Municipal Library of Heraklion, see ibid., 167–70, 179–82.

[15] See the General Plan and Iconographic Program of the Sanctuary Screens According to the Contract (1880).

[16] A detailed analysis of all the sources used and comparative studies of the works executed by the two Cretan artists are provided in Alevizou, “Archeiakes martyries.”

[17] For the previous work of the two Cretan artists and a general overview of the introduction of engravings, particularly those of Carolsfeld and Doré, in Cretan ecclesiastical painting, see Denise-Chloe Alevizou, “To epagelma tou zōgraphou stēn Krētē sta telē tou 19ou aiōna” [The profession of the artist in late 19th century in Crete], 11th International Cretological Congress, Rethymnon, October 21–28, 2011 (Proceedings publication forthcoming).

[18] In the 1840s Greece was ruled by the Bavarian King Otto. The reign of the young King Otto of Greece, son of King Ludwig I of Bavaria, commenced in 1832 (under the London Convention) and more specifically in 1835, after a three-year period of Regency, and lasted until his deposition in 1862. It was in 1833, during the Regency, when the autocephaly of the “Orthodox Eastern Church of the Kingdom of Greece” was proclaimed by royal decree. The king of Greece (who was, notably in this case, a Roman Catholic) was henceforth thus considered as its head having power to appoint the members of the Holy Synod, and whose permission was necessary for any acts to be passed by the Synod. The Church thus became, in essence, subject to the state. More importantly, the decree lead to an immediate breach with the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Patriarch Anthimos the Fourth, finally recognized the autocephaly in 1850, but only with the understanding that the Greek Church be governed without any secular intervention, a condition which was, however, in essence ignored.

[19] Greek bibliography was recently enriched with two important dissertations offering new insight on the issue of the “improvement of Byzantine art”: Nikolaos Graikos, “Akadēmaikes taseis tēs ekklēssiastikēs zōgraphikēs stēn Ellada kata ton 19 aiōna. Politismika kai eikonographika zētēmata” [Academic trends of ecclesiastical painting in Greece during the 19th century: Cultural and iconographic issues] (PhD diss., Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, School of Philosophy, 2011), Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, accessed March 20, 2011, http://invenio.lib.auth.gr/record/125564?ln=el%E2%80%8E, in which improvement is analytically presented together with an overview of Greek ecclesiastical painting throughout the nineteenth century; and Fani K. Spachidou, “Ē Vyzantinē technē ston ellēniko Typo tou 19ou ai.” [Byzantine art in the Greek press in the nineteenth Century] (PhD diss., Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, School of Philosophy, 2010), accessed December 13, 2011, http://invenio.lib.auth.gr/record/115173?ln=el, a well-documented account of articles, speeches, etc. published at the time, offering an overview of contemporary Greek sources on the discussion on Byzantine art and what was understood as “Byzantine” at the time. For the history and use of the term “improvement of byzantine art” by its Greek advocates see Graikos, “Akadēmaikes taseis,” 242–50. Additionally, see the treatment of the “improvement of byzantine art” as a “representational theorem” (anaparastatiko theōrēma) in Graikos’s introduction to “Akadēmaikes taseis,” lxxv; but see also Nikos Hadjinikolaou, Ethnikē technē kai prōtoporia [National art and the ideology of Avantgardism] (Athens: Ochima 1982), 20, in which improvement is considered as a “representational ideology” (parastatikē ideologhia).

[20] See Gregorios Papadopoulos’s 1870 speech “Peri tēs kath’ ēmas ekklēsiastikēs technēs kai idiaiterōs peri Ellēnikēs aghiografias” [On Eastern Greek ecclesiastical art and particularly on Greek icon-painting] Pandora, no. 485, (June 1, 1870), 102. The full text of the speech is also in Spachidou, “Ē Vyzantinē technē,” app. D1, 333–40. Gregorios Papadopoulos (1819–73), was a historian and Greek tutor who also taught art history at the School of Fine Arts in Athens. Among the other spokesmen of improved byzantine art, the most prominent were the Archimandrite Theoklitos Pharmakides (1784–1860), a fervent supporter of the autocephaly of the Greek Church; the architect and, for a period, director of the School of Fine Arts in Athens, Lyssandros Kaftantzoglou (1811–85); and the theologian and archaeologist Georghios Lampakis (1854–1914), one of the founders of the Christian Archaelogical Society.

[21] See Gerasimos Mavroyiannis, “Peri Vyzantinou Rhythmou” [On Byzantine style], Chrysallis, no. 1, January 1, 1863, 17, also quoted in Spachidou, “Ē Vyzantinē technē,” 46.

[22] Spachidou, “Ē Vyzantinē technē,” 177. It should be noted here that Spachidou’s observation is made in retrospect, since during the period the art of the Byzantine era still remained little known. For the first Greek efforts to collect and rescue “Christian art” at the end of the nineteenth century, and the first efforts towards the systematic study of the art of the Byzantine era in Greece in the next century, see for example Andreas Lapourtas, ed., 1884-1930: From the Christian Collection to the Byzantine Museum, exh. cat. (Athens: The Byzantine and Christian Museum - Greek Ministry of Culture, 2002).

[23] The Bavarians acknowledged very early on the importance of the legacy of ancient Greece as the most important factor in shaping the identity of the modern Greek state. For the Bavarian program for the “rebirth of the age of Pericles” under the reign of King Otto and particularly on neoclassicism in Athens, see Marilena Kassimati, ed., Athēna-Monacho: Technē kai politismos stēn nea Ellada [Athens-Munich: Art and culture in modern Greece], exh. cat. (Athens: Alexandros Soutzos Museum - National Gallery - Greek Ministry of Culture, 2000). Οn the shaping factors of Greek national identity in general and particularly in connection to the “Megali Idea” during this period see Elli Skopetea, “To Protypo Vasileio” kai ē Megalē Idea. Opseis tou ethnikou provlēmatos stēn Ellada (1830–1888) [“The Prototype Kingdom” and the Megali Idea. Aspects of the national problem in Greece (1830–1880)] (Thessaloniki: Polytypo, 1984). But see also Thomas W. Gallant, Modern Greece (London and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 68 on the two “opposed Greek identities”: “one as ‘Hellenic’ that emphasized western values that derived from antiquity and that de-emphasized the importance of Orthodoxy, and the other as ‘Romioi,’ Roman, that emphasized the oriental characteristics and traced its roots to the Orthodox Byzantine Empire.”

[24] See for example Spachidou’s observations on Kaftantzoglou’s views. Spachidou, “Ē Vyzantinē technē,” 84–92, 185–86.

[25] See the prologue to The Christian Archaeological Society Founding Statute (1885) (Athens: Korinis, 1901), a-c, signed by Georghios Lampakis (director of the newly founded “Museum of Christian Archaeology and Art,” and a fervent proponent of “improvement”), in which references to the history of Hellenism as “indivisible,” are followed by appeals for the collection and rescue of “Hellenic Christian art” of the Byzantine period as “tokens of faith, love and devotion,” the study of which is also now noted as “of grave national importance.” For publications during this period establishing “the long Greek history” (i.e., the first historical studies to include the Byzantine era in the history of Greece, thereby establishing the continuum of Greek history from ancient times through to modern-day Greece) see Konstantinos Th. Dimaras, Ellēnikos Rōmantismos [Greek Romanticism] (Athens: Ermis, Neoellinika meletimata-3, 1982), and esp. 421–25, 462–71 in reference to Konstantinos Paparigopoulos’s contribution.

[26] On this payback, or counter-loan (antidaneio) ideology, as used by the spokesmen of improvement, see in Spachidou, “Ē Vyzantinē technē,” 190–91.

[27] For the influence and impact of Nazarene art in Greece during the period see Dimitris Papastamos, Ē Epidrasē tēs nazarēnēs skepsēs stē neoellēnikē ekklēssiastikē zōgraphikē. Kōnstantinos Fanellēs, Ludovikos Theirsios, Spyridon Chatzēghiannopoulos, Kōnstantinos Artemēs [The Influence of nazarene thought in neo-Hellenic ecclesiastical painting. Konstantinos Fanellis, Ludwig Thiersch, Spyridon Chatzigiannopoulos, Konstantinos Artemis], exh. cat. (Athens: Alexandros Soutzos Museum - National Gallery, 1977).

[28] For contemporary texts on Thiersch’s work at the Russian church Soteiras Lykodimou (1853–55) see Spachidou, “Ē Vyzantinē technē,” 166–69. On his work as supposedly based on studies of the mosaics at the monastery of Daphni and St. Luke’s see Andreas Xyngopoulos, Schediasma istorias tēs thrēskeftikēs zōghraphikēs meta tēn Alōsin [An outline of the history of religious art after the Fall of Constantinople] (Athens: The Archaeological Society, 1957), 353–54. On the introduction and significance of the term “EllēnoChristianos” [Hellenic-Christian] during this period, see Dimaras, Ellēnikos Rōmantismos, 606n477.

[29] For the commission, impact, importance, and influence of Alexander Maximilian Seitz’s work at the cathedral of Athens on Greek ecclesiastical painting see Graikos, “Akadēmaikes taseis,” 296–98. For the efforts to modernize and Europeanize the modern Greek state and the importance of the European identity for Greeks both politically and culturally during this period see Skopetea, “To Protypo Vasileio,” 141–213.

[30] The expulsion of King Otto was followed by the reign of the Dane George I, “the king of the Hellenes.” He was nominated by the Great Powers, and reigned from 1863 until his death in 1913. In 1867 he married the Russian Christian Orthodox Olga Constantinovna, granddaughter of Tsar Nicholas I and first cousin of Tsar Alexander III; notably, it was Queen Olga and King George’s second son, Prince George (1869–1957), who was appointed High Commissioner of Crete by the Great Powers after the fall of the Ottoman rule (1898), during the transition period known as the Cretan State, or the period of Autonomy, which preceded the isle’s Union with Greece (1913).

[31] A detailed account of the various sources proposed is provided in Graikos, “Akadēmaikes taseis,” pt. B, chaps. 1–6, with extensive material and illustrations demonstrating their use by Greek artists.

[32] See for example the criticism for the use of the proposed Nazarene art prototypes as a foreign and dangerous influence on Greek national identity, and the severe criticism of Ludwig Thiersch’s role in Greek artistic education, in Mertyri, Ē Kallitechnikē ekpaidephsē, 156–60, and Spachidou, “Ē Vyzantinē technē,” 159–76. The issue of the “progressives” versus the “retrogressives,” is discussed at length in Spachidou, “Ē Vyzantinē technē,” 194–212.

[33] See Spachidou, “Ē Vyzantinē technē,” 189–90; and Graikos, “Akadēmaikes taseis,” 248.

[34] See Jeanne-Marie Musto, “Byzantium in Bavaria: Art, Architecture and History between Empiricism and Invention in the Post-Napoleonic era” (PhD diss., Bryn Mawr College, 2007), in which Musto argues that the “Byzantine Revival” had been central in the shaping of Bavarian identity and programmatically promoted by Ludwig I.

[35] The Eastern connection to Bavarian politics in reference to King Ludwig I’s political aspirations (which included the Bavarian program for the Byzantine Revival in Greece) is extensively discussed in Musto, “Byzantium in Bavaria.” The significance of the Eastern Question in connection to the art of the Nazarenes is also particularly underlined by Albert Boime, Art in an Age of Counterrevolution, vol. 3, A Social History of Modern Art (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 35. It should be noted that Greek bibliography lacks studies on the connection between Bavarian politics, Bavarian nationalism, and the role played by Nazarene art in the Bavarian program of the “Byzantine Revival” in Greece and the East. However, political patronage of Nazarene artists during the reign of King Otto is well documented in Greek studies. One need only refer to the appointment of Ludwig Thiersch as professor at the School of Arts in Athens, or to the impact and symbolic importance of commissions such as to Cornelius’s pupil Alexander Maximilian Seitz, for the central cathedral church of the Annunciation (1860) to sufficiently demonstrate the significance of Bavarian politics and Nazarene art in Greece—a significance which was also acknowledged by contemporaries (see the criticism quoted in Mertyri, Ē Kallitechnikē ekpaidephsē, 156–60, and Spachidou, “Ē Vyzantinē technē,” 159–76).

[36] In contrast to Bavarian politics and the “Byzantine Revival,” well established in Greek bibliography is the connection between Russian geopolitical strategies on the Eastern Question and Russian artworks and their dissemination in Greece during this period, mainly via the workshops of Russian monks who had settled in 1833 at Mount Athos. Graikos, “Akadēmaikes taseis,” 502–10, 506n844.

[37] For an overview of the Cretan Question, Great Power strategies, and the Cretan revolutions during this period see Leonidas Kallivretakis, “A Century of Revolutions: The Cretan Question between European and Near East Politics,” in Eleftherios Venizelos: The Trials of Statesmanship, ed. Paschalis M. Kitromilides (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006), 11–35, HELIOS, National Hellenic Research Foundation, accessed April 20, 2013, http://helios-eie.ekt.gr/EIE/handle/10442/8787.

[38] See “Ypomnēma tēs Genikēs tōn Krētōn Synelephseōs, en Argyroupolei, 3 Fevrouariou 1878” [Memorandum of the General Assembly of Cretans, Argyroupoli, 3rd of February 1878], Talos, vol. D (1994), 661.

[39] See “antistavrophoria” [anti-crusade] as used in reference to the bombardment of Crete by the Great Powers in 1897 in “Diamartyria kai ekklēssis Epanastatikēs Epitropēs. Pros tous Christianikous laous tou pepolitismenou kosmou, 10 Fevrouariou 1897” [Protest and appeal by the Revolutionary Committee. To the Christian nations of the civilized world, 10th of February 1897], Talos, vol. D (1994), 688.

[40] Indicative of the difficulty in openly taking sides is the acknowledgment by the Metropolitan Bishop of Crete Timotheos Kastrinoyiannakis, in 1884, of the position of the Church of Crete between, on the one hand, “the duty towards the Great Mother Church of Christ [Ecumenical Patriarchate]” and, on the other, the duty towards the beloved country and its parliament. For the text in Greek see “Pros ta Christianika melē tēs Genikēs tōn Krētōn Synelephseōs” [ To the Christian members of the General Assembly of Cretans], Minos (Heraklion), August 11, 1884. It is important to note that a series of issues during this time created great turmoil for the Cretan Church: the so-called Monastic Issue, followed by the “Episcopal Issue,” followed later by the “Metropolitan Controversy.” In addition, there was the division between those who expressed allegiance to the Ecumenical Patriarch Joachim III, known as Joachimites, and those who opposed him, known as anti-Joachimites. Beyond internal strife and power struggles among the prelates of the Cretan Church, these issues entailed secular-political, Sublime Porte, Greek state, and Great Power intervention at various levels, which were all part of Cretan Question strategies related to the role and power of the Church in Crete as subject to the Ecumenical Patriarchate. For a brief overview of the history of the Cretan Church of this period see Theocharis Detorakis, History of Crete, trans. J. C. Davis (Heraklion: printed by author, 1994), 399–403; and for a detailed analysis of that history, particularly on the stance of the official Cretan Church toward the claim for Crete’s Union and towards the autocephaly of the Greek Church, see Archimandrite Andreas Nanakis, Ē Ekklēsia tēs Krētēs stēn epanastasē tou 1897–1898. Apo tēn ethnarchikē stēn ethnikē syneidēsē [The Church of Crete in the Revolution of 1897–1898. From the ethnarchic to the national consciousness] (Thessaloniki: Pournaras, 1998).

[41] Father Michail Vlavogilakis has recently published a richly documented study on the topic: Michail Vlavogilakis, Ekklēsia kai agōnes tēs Krētēs 1856–1905 [The Church and the Cretan struggles 1856–1905] (Chania-Crete: ‘Eleftherios K. Venizelos’-Metropolis Kydonias and Apokoronou, Sideris Publications, 2011).

[42] See the General Plan and Iconographic Program of the Sanctuary Screens According to the Contract (1880).

[43] For the copies of Seitz’s works in Cretan churches see Alevizou, “To epagelma,” (publication forthcoming). For images of the works see Graikos, “Akadēmaikes taseis,” 1066.

[44] As pointed out by Thomas Gallant: “By combining the celebration of the birth of the nation with the Christian festival of the Annunciation, the bond between religion and nationalism was drawn even tighter. The day on which the announcement of the coming of Christ was made thus became now also the day on which the birth of the new nation was foretold.” Gallant, Modern Greece, 69.

[45] After the 1866 revolution it was also common practice for revolutionaries and the organized body of the Cretan Assembly of Insurgents to swear oaths of allegiance to King George. See “Psēphisma Genikēs Synelephseōs Krētōn. Kēryxē tēs Enōseōs, en Sphakiois tēs Krētēs, 21 Avgoustou 1866” [The Resolution of the General Assembly of Cretans. Declaration of the Union, in Sphakia Crete, 21st of August 1866], Talos, vol. C (1991-93), 417–18. Many other revolutionary texts, declarations, memorandums, etc. ended with acclamations to King George of the Hellenes. Such expressions of allegiance to the king did not, however, prevent expressions of bitterness for the ambivalent and often reluctant stance of the Greek state to help the Cretan struggle and the Cretan cause.

[46] “PŌS EKATHĒSE MEMONŌMENĒ Ē POLIS Ē PLĒRĒS LAŌN KATESTATHĒ ŌS CHĒRA. AKATAPAPHSTŌS KLAIEI TĒ NYKTA, KAI TA DAKRYA TĒS REOUN EPANŌ EIS TAS SIAGŌNES TĒS.”

[47] For the extant compositions today placed one above the other, see fig. 4. For the possible original placing of these icons on the sanctuary screen dedicated to the Transfiguration see the General Plan and Iconographic Program of the Sanctuary Screens According to the Contract (1880) and the relevant note.

[48] The proclamation of Alexandros Ypsilantis “Machou yper Pisteōs kai Patridos,” [Fight for Faith and Motherland] was issued on February 24, 1821 at Iasi.

[49] See for example “Ypomnēma Krētōn pros tis Megales Dynameis. To aitēma tēs Enōseōs, 15 Maiou 1866” [Memorandum of the Cretan people to the Great Powers. The claim for the Union, 15th of May 1866], Talos, vol. C (1991-93), 414, or the long account of the unfairly ongoing war as described in “Ypomnēma tēs Genikēs tōn Krētōn Synelephseōs,” 654–63.

[50] For the dissemination and importance of the icon particularly in relation to its role in support of the Cretan struggle see Michalis Troulis, “Ē Systasē tou ‘Philekpaidephtikou Syllogou Krētōn’ stēn Ermoupolē tēs Syrou (23 December 1859)” [The Founding of the “Cretan Society of Friends of Education” at Hermoupolis, Syros (23 December 1859)], in Proceedings of the 7th International Cretological Conference, 1994-95, vol. C, bk. 2 (Rethymnon: Holy Metropolis of Rethymnon and Avlopotamos, 1995), 597-608 esp. 606n48 and 607n51. For the worship of these saints in Crete in general and their significance see Theocharis Detorakis, “Oi Aghioi tēs prōtēs vyzantinēs periodou tēs Krētēs kai ē schetikē pros aphtous philologhia” [The Saints of the first Byzantine period in Crete and the relevant literature] (PhD diss., National Kapodistrian University of Athens, School of Philosophy, 1970. See also Emmanouil Vyvilakis’s use of the icon of The Ten Martyrs of Crete as a symbol against Catholic propaganda during the earlier period 1840–1860, and as discussed in Michalis Troulis, Emmanouēl Vyvilakēs. Ē Zoē, ē drasē kai to ergo tou [Emmanouil Vyvilakis. His life, activity and work] (Rethymnon: printed by author, 2005).

[51] Indicative is the case of the icon The Three Hierarchs on the central middle zone of the sanctuary screen at the cathedral church of Rethymnon, paid for and dedicated by the children of the three public schools of the city, in June 1859.

[52] For a contemporary source on the connection and promotion of the Three Hierarchs as a symbol of the Cretan cause, see indicatively Prof. Dorotheos Klonarakis’s speech on the occasion of the feast-day of the Three Hierarchs published in the newspaper Minos (Heraklion), February 25, 1884.

[53] See Panaghiotis Christou, “Istorika stoicheia peri Krētēs en tē pros Titon epistolē tou Apostolou Pavlou” [Historical facts regarding Crete in the Epistle of Apostle Paul to Titus], Cretica Chronica 4 (1950): 281–93.

[54] Epimenides of Knossos, a semi-mythical figure, is supposed to have lived in the 7th or the 6th century BCE. A Cretan seer famous for his legendary advanced age (157 or 299 years), his miraculous sleep of 57 years, his dealings with oracles, his wanderings outside the body. He was credited with having conducted purificatory rites at Athens in about 500 BCE and was also a reputed author of religious and poetical writings, including a Theogony, Cretica, and other mystical works. On Epimenides’s denunciation of the Cretans included in his Cretica and as quoted by the Apostle Paul, see Panaghiotis Christou, “O Apostolos Pavlos kai to tetrastichon tou Epimenidou” [Apostle Paul and the verses of Epimenides], Cretica Chronica 3 (1949): 118–26; and Christou, “Istorika stoicheia,” 290–92, where its use as a warning to Titus is considered as part of the effort of the religious reformer to address the on going worship of Zeus in Crete.

[55] For Apostle Paul as particularly revered in Athens and the iconography of Apostle Paul Preaching in Athens as used by theologians in their argumentation for legitimizing the autocephaly of the Church of Greece during this period, see the observations and the relevant bibliography noted in Graikos, “Akadēmaikes taseis,” 649.

[56] In order to establish what is considered “usual” placement or to find an established canon for the placement of icons on sanctuary screens during the specific period, comparative studies of various iconographic programs of sanctuary screens remain necessary. However, the central placement of an Old Testament composition in the gable of a sanctuary screen (below the crowning piece and above the dodekaorton, i.e., the icons of the great feasts of the Christian Orthodox liturgical year which all bear compositions based on the New Testament) is extremely unusual.

[57] “Logos ekphōnētheis en tō kathedrikō naō tou Aghiou Mēna ypo tou Sevasmiōtatou Mētropolitou Krētēs Kyriou Kyriou Timotheou kata tēn anarrhēsin Aphtou tē 22 Septemvriou 1882” [Speech given in the cathedral Church of St. Menas by the Very Rev. Metropolitan Bishop of Crete Timotheos on the occasion of his enthronement, on the 22nd of September 1882], Minos (Heraklion), September 25, 1882.

[58] See for example passages from revolutionary texts as early as 1830 and 1841 in Talos, vol. C (1991-93), 402-403, and in Ioannis Mourelos, Istoria tēs Krētēs [History of Crete] (Heraklion: Elephthera Skepsis, 1950), vol. B, 905–9. See also the various studies and theses on the Cretan heritage of the laws written by Cretans during this period, as, for example, the unpublished study by Stefanos Xanthoudidis, “Peri Eunomias,” [On Eunomia] archive ref. Xanthoudidis 6, no. 21, archives of the Historical Museum of Crete-Kalokairinos Foundation, Heraklion; and Minos Kalokairinos, “Nomothesia tou Vasileōs tēs Krētēs Minōos” [The Legislation of Minos king of Crete] (PhD diss., Law School, University of Athens, 1902).

[59] For the “resurrection of Crete,” as a commonplace reference during this period, see indicatively the official letter written in 1897 and addressed to the Defense Commission at Archanes by the fervent unionist Bishop of Petras, Titus Zographides (quoted in Nanakis, Ē Ekklēsia tēs Krētēs, 136), ending with: “May God, who was crucified and resurrected for the salvation of Man resurrect our country, from its subjugation to the heathen and barbaric nation.” For a contemporary reference on icons of the Resurrection in connection to the “resurrection of Crete,” see, for example, Dionysios Marangoudakis, To Ieron kai ēroikon tēs Krētēs Arkadi [The Sacred and heroic monastery of Crete Arkadi], written between 1911-12 but published later (Athens: Printed by the author’s family, 1989), 74, which relates that the miraculous saving from the flames at the Holocaust of Arkadi in 1866 of the crowning icon of the Resurrection from the sanctuary screen of the main church of the monastery of Arkadi had been considered by all at the time as a good omen, signifying “Crete’s and Hellenism’s forthcoming resurrection.”

[60] For the Resurrection in Greek history painting and as connected to the Greek War of Independence see examples noted in Graikos, “Akadēmaikes taseis,” 764.

[61] Notably, the theme of the anticipated resurrection is repeated in the middle and lower zones or registers of the screen: its central composition is The Transfiguration of Christ—a copy by Ioannis Stavrakis of the upper part of Raphael’s Transfiguration, in the middle zone—and the lower zone composition of Jonah Cast Forth by the Whale (Matt. 12:40), a copy by Antonios Alexandrides of Doré’s engraving, is an Old Testament prefiguration of the Resurrection (see both compositions in the detail of the sanctuary screen, fig. 5).

[62] The congregations could view both screens at all times (fig. 2). Moreover, it seems that the two artists intentionally aimed for unity from the outset since, as documented by archival evidence, they chose to work together in all the registers or zones of both screens. See a detailed analysis of their works in Alevizou, “Archeaikes martyries.”

[63] In this sense, and in relation to Eastern Orthodox typology, it would be true to say that the artists did in fact adhere to “the type (typos) accepted by the Eastern Orthodox Church,” as demanded by the 6th clause of the contract. Interestingly, too, the fact that the Cretan Church authorities chose primarily Nazarene art prototypes to allude to Crete’s identity and the Cretan claim for the island’s union with Greece, via the metaphor of the Exodus of the people of Israel before their entry to the “promised land,” poses the question of whether these works were also intended as an Eastern Orthodox answer to supersessionism. For an extensive discussion of supersessionism and anti-Judaism in Nazarene art see Cordula Grewe, “A Family Tree of German Art: Avant-garde, Anti-Judaism and Artistic Identity,” chap. 6 in Painting the Sacred in the Age of Romanticism (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009).

[64] The Sultan had resigned all his rights over Crete on May 30, 1913 (Article 4 of the Treaty of London), but the formal declaration of the island’s union with Greece was finally realized on December 1, 1913 when the Greek flag was raised on the castle of Firka at Chania, in the presence of King Constantine, the king of Greece, and Eleftherios Venizelos the prime minister of Greece. For a brief history of the events which lead to the formal union of Crete with Greece see Detorakis, History of Crete, 420–22.

_125_100.png)

_125_100.png)