The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Milcendeau, le maître des regards

L’Historial de la Vendée, Les Lucs-sur-Boulogne

April 7 – July 8, 2012

Catalogue (fig. 1):

Charles Milcendeau, sa vie, son oeuvre, 1872–1919.

Edited by Christophe Vital.

Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2012.

304 pp. 246 color illus; 29 b/w illus; bibliography.

35 €

ISBN: 9 788836 623198

While the best-known students of Gustave Moreau, one of the leading teachers at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in the late nineteenth century, remain Henri Matisse and Georges Rouault, we should consider another pupil who had a significant early career, but whose production remains known largely to specialists and collectors. This is not to say that Charles Milcendeau is less deserving of attention, although the reasons for the obscurity of his work today has to do with the fact that he remained a late naturalist, largely drawing on the people and scenes of his native Vendée on the west coast of France, rather than becoming a creator who forged new directions under the banner of modernism. To appreciate Charles Milcendeau, as was recently revealed in the excellent retrospective exhibition of one hundred and fifty–nine of his works at the Historial de la Vendée, requires a willingness to go beyond well trodden paths (fig. 2). A visitor must become interested in scenes linked to the life of the peasant, and recognize an artist of infinite power and insight whose best works were often done as charcoal drawings, pastels, or gouaches on a very intimate scale. Only then will the visitor be able to grasp the artist’s range as presented in the comprehensive exhibition at the Historial de la Vendée, in Les-Lucs-sur-Boulogne, an isolated location, far from Paris, and accessible only by automobile or bus (fig. 3).[1]

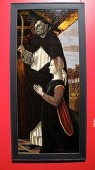

Organized as a series of interlocking thematic sections, the exhibition followed the arc of Milcendeau’s life, providing evidence of the types of work he completed at various moments in his career. From the first, Milcendeau was presented as an independent personality, an artist who enjoyed considerable success at the beginning of his career through exhibitions in Paris and thanks to supportive collectors who secured his work. The first wall text panel made the case as to why the exhibition was organized: to provide a substantial picture of his career and demonstrate that he deserved considerably more attention than he had so far received (fig. 4). The show began with the work that the artist completed at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts while under the tutelage of Gustave Moreau. Following Moreau’s advice, and in keeping with the traditional teaching at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Milcendeau spent time in the Louvre copying, in 1894, a work by Ambrogio Bergognone (ca. 1470s–1523/24) the right panel of an altarpiece documenting his skill early in his career (fig. 5).

Other works in this section show an emotionalized treatment of religious scenes such as the Pietà or the Flagellation of Christ. These works, with their distorted, expressive forms, their rich use of brilliant color, and their ability to create original compositions, provide visual evidence that Milcendeau could have moved in another direction, away from naturalism, if he had wanted to. These early works are also highly suggestive of one of his fellow colleagues at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts as they anticipate the direction of George Rouault’s work later in this artist’s career (fig. 6).[2] From these early works, establishing Milcendeau as an artist of verve and originality, the exhibition moved into an area where Milcendeau was going to excel. In this next section, his dedication to draughtsmanship above all else became the predominant message.

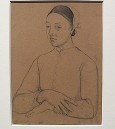

With drawings, certain basic characteristics of Milcendeau’s approach were immediately recognizable. All of them revealed that he worked without artifice, showing his sitters or scenes as they actually appeared. He often presented views of the interiors of the homes of the Vendean peasant without modifying the dour atmosphere; the scenes provided a somber environment appropriate to their lives and the actual setting (cat. no. 68, fig. 7). More than this, Milcendeau’s precise, expressive line suggested relationships with earlier artists; there are echoes in his work of a close observation of Jean Clouet (1480–1541), Hans Holbein (ca.1497–1543) and even Honoré Daumier (1808–79) as in Le Paysan mangeant sa soupe (Peasant Eating his Soup) (1898) (cat. no. 5, fig. 8). Many drawings were of his family members, especially his father; others were of Vendean peasants drinking, suggestive of paintings from the seventeenth century by Adriaen Brouwer (1605–38), an artist that Milcendeau obviously knew quite well. When Milcendeau worked as a pastellist, his works increased in expressiveness providing evidence of the ways in which he accurately remembered Brittany peasants as in Bretonne devant les falaises d’Ouessant (Breton Woman in Front of Ouessant Cliffs) (1898) (cat. no. 80, fig. 9). While many other artists had gone to Brittany to record the people and their ceremonies, Milcendeau’s series of Brittany types, wearing traditional dress, reveals his dedication to, and love for, the people of the region he knew so well. He wanted to be truthful to the way they looked, dressed, and to the experiences that shaped their faces, and their postures (cat. no. 65, fig. 10). Much as Emile Zola recorded his impressions of different locations and people in his notebooks in preparation for his novels, Milcendeau’s drawings used a similar method of objective analysis heightened by a psychological intensity appropriate to the model’s personality. The only difference here was the fact that these drawings were not studies leading to other usages; they were meant as the finished response to a scene or sitter. Milcendeau wanted his vision to be undisturbed, he did not try to change the depiction of a person or view or use it for another purpose: the drawing or pastel was the finished work. He valued drawing above everything else, a quality that was deeply appreciated by collectors at the end of the nineteenth century who treasured what the artist was trying to achieve.

In the next exhibition section, “Les Portraits Mondains,” Christophe Vital revealed that Milcendeau had the support of prominent collectors and influential art critics, including Gustave Geffroy. In 1898, owing to the critic’s patronage, the Galerie Georges Petit organized an exhibition in Paris that further established the artist’s reputation. Milcendeau added to his repertoire of peasant imagery to include portraits of some of his primary supporters such as Charles Hayem, a major patron of the Louvre and a collector of Milcendeau’s work (cat. no. 86, fig. 11). Among other individuals was Alain Jammes d’Ayzac, who eventually published a book on Milcendeau in 1946.[3] As evidenced by the examples of fashionable portraits in the exhibition, Milcendeau could have become a distinguished portraitist if that had been his intention. However, as other sections of the exhibition demonstrate, this was not what Milcendeau had in mind for his career. He cherished his independence, and was unwilling to compromise in spite of the sacrifices he had to make in order to remain true to himself and to his goals.

Spain was the subject of the fourth section of the exhibition; this country became Milcendeau’s second home (fig 12). By 1901, with the artist Francisco Iturrino (1864–1924), Milcendeau immersed himself in Spanish artistic culture in Madrid. Here he absorbed the masters of Spain’s golden age; he also began his study of gypsies, a theme that became increasingly prominent in his work. Looking for a location that mirrored what he found in France, Milcendeau went to Ledesma, a medieval city not far from Salamanca. He drew inspiration from the poverty of the people in this region, becoming immersed in the severity of what is regarded as “Black Spain” because of the misery of the inhabitants. For nine years Milcendeau worked sporadically in the region, supported in his work by the Spanish artists Iturrino and Ignacio Zuloaga (1870–1945). The works he produced in Spain reflected his growing interest in using pastels as his medium of choice. Whether he was doing studies of Gitanes (Gypsy Women) (cat. no. 98, fig. 13) or major pastel studies of old women as in his Fileuse bretonne (Breton Spinner) (cat. no. 13, fig. 14), Milcendeau’s intensity of observation deepened, the sympathy he shared with his models increased. His majestic La mère et les deux enfants(Mother and Two Children) (1901) attests to the way in which the French government responded to his work. It was purchased by the French state, under the artistic guidance of Léonce Bénédite, then Director of the National Museums, and hung in the contemporary art museum in Paris at the time.[4] Other pastels, such as his La famille autour du berceau vide (The Family Next to the Empty Cradle) (1909) suggests that the somber life of the peasant was being used as a visual metaphor for a deeply religious existence (cat. no. 123, fig. 15). The piety of these humble types could instill in others the importance of dedication and hard work. Since these drawings and pastels were well known at the time, and were exhibited in major French museums and in gallery shows, the influence they could have had on other artists, including early works by Pablo Picasso, is decidedly palpable, although not explained in the exhibition itself or in the excellent accompanying catalogue.

The fifth section of the exhibition examined a change of direction. In 1909 Milcendeau abandoned Spain, returning to France and occasionally traveling to the rugged countryside of Corsica. He then expanded his artistic parameters, as he felt more comfortable working in oils, a medium that he had been trained to use well at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, but with which he still felt insecure. The insecurity vis-à-vis painting is a recurring theme of the artist’s observations as recounted by Jammes d’Ayzac in his book on the artist. He returned to the Vendée and the people he knew well as his neighbors who, once again, became his chosen models. Living in the Vendée, at Bois-Durand, Milcendeau constructed his own universe where his modest home, decorated with wall murals (and ceramic tiles that suggest Spanish sources) he retreated inward. His health, which had never been strong, became a major concern. He focused on the lives of his friends, the people who lived in the marais, the marshes; he used them as character studies, recording their habits, their over indulgence in the illusory pleasures of smoking and drinking as fervent morality plays for the improvement of life. Among the best works from this phase of his career are L’Avare (The Miser) (1912) (cat. no. 135, fig. 16) and Les Deux Compères (The Two Friends) (1914) (cat. no.136, fig. 17), the work used by the exhibition organizers to serve as the symbolic example of his mature approach as well as the cover of the catalogue and the image used in publicity about the exhibition. (This image was also used on the site of the electronic magazine Tribune de l’Art).

The concluding section of the exhibition revealed another side of the artist’s talent; Milcendeau toward the latter part of his life had become a major landscapist (fig. 18). Hiding in the Bois-Durand (his home near Soullans) during World War I, Milcendeau fought depression and the deterioration of his health. Unable to exhibit works at the Salon in Paris, forgotten by those who had earlier championed his compositions, Milcendeau continued to work. With little amelioration of his condition, and only the steadfast dedication of his wife and a few friends, he tried to blot out the effects of World War I and his own deteriorating mental health. The marais became the symbol of life, his life, and while many of the scenes are painted with tones of grey, they possess a sweep and assuredness that link Milcendeau with the major landscape painters of the Dutch seventeenth century such as Jacob Ruisdael (1628–82). Whether one examines, Départ pour le baptème (Leaving for the Baptism) (1916) or Avant la grêle (Before the Hail Storm) (1917) (cat. no. 150) or Le Bois–Durand par temps gris (Le Bois-Durand Under a Grey Sky) (1916) (cat. no. 151), Milcendeau created a late style, a vision of his own world, where his steadfast desire to record his feelings is found in majestic, sweeping landscapes, which are the final superb summation of his artistic career (figs. 19 and 20).

It is to the credit of the organizers of this exhibition that all facets of Milcendeau’s career were presented with care and insight. Since there is so little information available on the artist—either in print or on the internet—the show provided an opportune moment for individuals to see the broad range of his work in a series of carefully selected examples drawn from museums and collections all over the world. While the tendency might have been to see Milcendeau as a regional artist, one solely linked to the peasants of the Vendée, this exhibition dispelled this notion. In its place, Milcendeau emerges as an artist of genuine significance, one who moved naturalism into the twentieth century by infusing this tradition with a depth of feeling and personal observation that demonstrates that Milcendeau is both an artist with a deeply personal vision and a creator with the capacity to move his viewers by the intensity of his approach. He is to be valued in the future and not solely collected by a few.

Gabriel P. Weisberg

University of Minnesota, Department of Art History

vooni1942[at]aol.com

[1] L’Historial de la Vendée is a history museum dedicated to the history of the Vendée in general, and more specifically to the French Revolution and the War of the Vendée.

[2] See Charles Milcendeau, sa vie, son oeuvre 1872–1919, ed. Christophe Vital (Milan: Silvana Editoriale Spa, 2012): 116–121.

[3] Alain Jammes-d’Ayzac, Un Peintre–Un Pays Charles Milcendeau le Maraichin (Paris: Éditions de Flore, 1946). See also the new edition of the book published in 2005 with a preface by Christophe Vital.

[4] See Charles Milcendeau, sa vie, son oeuvre (2012) for a reproduction of La mère et les deux enfants, 1901. Pastel lined with canvas, 105 x 85cm. Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, deposited at the Musée des Beaux-Arts, La Rochelle.