The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Lorenzo Bartolini: Scultore del bello naturale

Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy

May 31 – November 6, 2011 (extended to January 8, 2012)

Catalogue:

Lorenzo Bartolini: Scultore del bello naturale

With essay contributions from Cristina Acidini, Silverstra Bietoletti, Leticia Azcue Brea, Annarita Caputo, Maria Theresa Caracciolo, Maria Virginia Cardi, Grégoire Extermann, Franca Falletti, Andrea Grecco, Michele Gremigni, Elena Karpova, Anna Gallo Martucci, Barbara Musetti, Ettore Spalletti, Caterina Olcese Spingardi, and Lucia Tonini.

Florence and Milan: Giunti Editore S.p.A., 2011. (Italian and English editions).

384 pp. with 95 color and 262 B&W illustrations; bibliography.

48 €

ISBN 978-88-09-76733-1

Sometimes there are things in life for which one must give thanks. Late in November last fall, I was fortunate enough to see Lorenzo Bartolini: Scultore del bello naturale (Lorenzo Bartolini: Beauty and Truth in Marble) at the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence. The exhibition was supposed to have closed on November 6, but I walked into it on November 24—which was Thanksgiving Day back in the States—when it was still full with visitors and, as far as I could tell, had every sculpture still in place. (I later learned that while some works were removed or replaced with comparable substitutions in December, the bulk of the original exhibition was extended through January 8, 2012.) The Accademia has been, for a long time, the caretaker of Bartolini’s numerous plasters, held since 1889 in their “Gipsoteca Bartoliniana,” and which underwent a painstaking restoration in 1985 (plaster cast room, fig. 1).[1] In her introduction to the exhibition in the catalogue, the Accademia’s director, Franca Falletti, notes that one of the reasons for holding this exhibition on Bartolini was that there were “more or less joking voices” suggesting that the Gipsoteca be used to turn a profit as a space for “spectacular exhibitions.”[2] (At least these “joking” voices still considered keeping the space as cultural space: in the United States they would have leased the space to Starbucks and they would not have been joking.) Falletti, the exhibition curators, and the catalogue contributors wanted to create an exhibition that would reintroduce Lorenzo Bartolini (1777–1850) to a new public and that would also justify the use of the Gipsoteca as the open storage and viewing space for his plasters. The exhibition also gave the team an opportunity to reevaluate the holdings in the Gipsoteca and Bartolini’s oeuvre as a whole. According to the museum’s press release for the exhibition, this was the first major retrospective to be held of Bartolini’s work.

The exhibition proper was held in a long corridor-like space, small but not overly crowded with works, in a separate area from the Gipsoteca, and was divided into three parts: “Il period francese” (“The French Period”); “Il purism e la committenza internazionale,” (“Purism and International Clientele”), and “Il bello naturale” (“Natural Beauty”). The first part, “The French Period,” covered Bartolini’s youth in Paris. Starting in 1799 he studied in the studio of Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), and while there he befriended other young artists there such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) and Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret (1782–1863), with both of whom he shared working quarters at the Convent of the Capuchines on the Rue de la Paix. With Ingres, Bartolini worked on the Musée Napoléon, and he was inspired by the work in the newly opened Musée des Monuments Français at the cloister of the Petits-Augustins. Later, Napoleon sent Bartolini to Carrara to direct the sculpture school there. Bartolini was a Bonapartist and benefitted from direct commissions from Napoleon I and his family. Bartolini’s fifteen years in France were more than formative: when he returned to his native Italy after the fall of Napoleon I, he was considered “French,” and thus he experienced some difficulty gaining commissions from Italians. Visitors to the exhibition were presented with portraits of Ingres and Bartolini, each made by the other; copies of works Bartolini made after his compatriot, the Neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova (1757–1822), and the very lovely Napoléone Elisa with her Dog (1812) borrowed from the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rennes (fig. 2). Napoléone Elisa is depicted as Hebe, cupbearer to the gods, a subject popular at the time and one that Canova had also treated.[3] Elisa’s nudity may have been disconcerting to some contemporary viewers, but her chubbiness alludes to her youth and innocence, and her control of her greyhound alludes to the idea that she is herself both calm and calming.

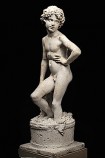

In the second part of the exhibition, “Purism and International Clientele,” viewers were introduced to the style of Italian Purism in post-Canovian sculpture.[4] Purism (sometimes called “Florentinism”) in the nineteenth century was an Italian style in painting and sculpture that moved away from the idealized ancient classicism found in Neoclassicism and towards an emphasis on realistic detail and emotional sentiment.[5] Purist artists of the period were closely aligned with Romanticism, and they were strongly influenced by the Italian quattrocento, especially because of that period’s naturalism and emphasis on spirituality. To make this point visible, the curators displayed a portrait of a woman with flowers by Bartolini that was very similar in its arrangement to Andrea del Verrocchio’s Lady with Primroses (1475–80) borrowed from the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence. An excellent example of a Purist sculpture, Bartolini’s Grape Presser (also called Young Bacchus, ca. 1820), a marble loaned by the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, was also exhibited here (fig. 3). One could almost feel the experience of the young male nude, with his feet buried deep in the sticky softness of the perfectly carved, little round grapes. The influence of Verrocchio persists here in the boy’s posing, which recalls his David (ca. 1465). Also in this section, visitors were given the sense and the breadth of Bartolini’s international reach through examples of his portrait busts: his clients included George Gordon, Lord Byron (whose portrait Bartolini finished only two years before Byron’s death); the American wife of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Fanny; the English industrialist Thomas Wilson Patten; the Spanish-Cuban banker Diego Peñalver; the Russian beauty Marina Dmitrievna Gurieva (née Naryshkina); and most importantly the Russian Demidoff family (especially Paul and Anatole Demidoff), for whom Bartolini made some of his most important works.

In a separate text, Sandra Berresford has noted that Bartolini was central to the Purist movement because he “revolutionized Italian sculpture by preferring the 'natural beauty’ of the Renaissance over the 'ideal beauty’ of the Greeks.”[6] This was the theme of the third part of the exhibition, entitled “Natural Beauty.” The highlight of this section was without doubt the supple and emotion-filled life-sized sculpture entitled Faith in God (1834–35) borrowed from the Museo Poldi Pezzoli in Milan (figs. 4, 5, and 6). In the nineteenth century, before finally reaching the patron Marchesa Rosa Poldi Trivulzio, the sculpture caused a sensation in Florence, Parma, and Brera where it traveled.[7] The sculpture was widely influential, inspiring many sculptures of young girls, both nude and clothed, shown in a spiritual trance, including Hiram Powers’ The Greek Slave (1844) and Vincenzo Vela’s La Preghiera del mattino (Morning Prayer) from 1846.[8] While Vela was not included in the exhibition or catalogue, there is no doubt we will learn more of Bartolini’s influence on Vela (which was quite strong) when the Museo Vincenzo Vela presents Bartolini’s drawings, an exhibition currently in development. Faith in God is the ultimate example of Tuscan Purism, combining the naturalistic study of anatomy with a sense of the spirituality one also finds in fifteenth-century art. Every inch of this marble is perfect, from the perfect curls of hair in front of the ears and the creases of skin at the soles of the feet. The figure’s nudity symbolizes perfectly her unblemished (read: virginal) body, her human vulnerability, and the innocence and purity of her heart and soul. A detail of the hands in prayer exhibits Bartolini’s excellent attention to the most subtle anatomical features (fig. 7).

There were three sculptures included in this final part of the exhibition that would have been of particular interest to American visitors: Horatio Greenough’s Gino Capponi (1840), a bust version of Powers’ The Greek Slave, and the plaster model of the Demidoff Table (ca. 1845). Greenough’s bust was a gift from him to the city of Florence, in gratitude for his long sojourn there. Annarita Caputo’s catalogue essay discusses the connections between Bartolini and Greenough, including the latter artist’s drawing after the Grape Presser. The bust of The Greek Slave by Powers was recently purchased by the Palazzo Pitti in 1995. Both artists knew Bartolini while they were residing in Florence (Greenough introduced Powers to Bartolini) and, according to Caputo’s essay in the catalogue, “it was Bartolini’s influence that prompted [Powers] to work from live models, to study anatomy, to heighten a sensitivity for delicately natural forms and to dedicate utmost attention to polishing the marble.”[9] The use of nudity as a symbol of one’s purity and innocence, as seen in Powers’ sculpture, is highly characteristic of Tuscan Purism.

The final work, the plaster model for Bartolini’s Demidoff Table, was interesting to see because the marble version is a well-known work in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 8). Made for Anatole Demidoff, the table once turned on its base, an idea that Bartolini possibly borrowed from Canova’s Paulina Borghese as Venus Victrix (1805–08, Galleria Borghese, Rome), which also rotated on its base. The Demidoff Table utilized allegories of love (its original title was La Table aux Amours) and focuses on the enjoyment of earthy pleasures over rational thought. The catalogue is instructive in showing how much detail is left out of the plaster model in comparison with the finished marble, which is rich in floral elements and signs of the zodiac on the edging of the table.[10] Other important works in this final section of the exhibition included Bartolini’s Nymph with a Scorpion (1843–44), shown in the Paris Salon of 1845 and which immediately registers as an influential source for the later, and more scandalous, Woman Bitten by a Snake (1847) by Auguste Clésinger (fig. 9). The marble used for Bartolini’s Nymph is creamy white, and he perfectly renders, in hard, cold marble, the sense of the soft, warm silkiness of young skin. The facial expression of the Nymph is not overly pained, but the way in which she pulls back her big toe to check her wound is strikingly real.

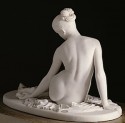

Bartolini could not completely ignore the ancient sculpture constantly in his midst, both in Italy and at the newly-established museums in France and they informed his exploration of natural beauty. As noted in the catalogue entry by Isabelle Leroy-Jay Lemaistre, his Nymph with a Scorpion has links in pose with the ancient sculpture Girl Playing Astragaloi (“Knucklebones”) from 130–150 AD. Similarly, Bartolini’s marble Dirce (also called Bacchante, ca. 1834), now owned by the Louvre, is posed similarly to the ancient Sleeping Hermaphrodite (fig. 10). One of the ten known versions of the Sleeping Hermaphrodite was purchased by the Louvre in 1807; undoubtedly Bartolini saw it there during his French period. Dirce sits up rather than reclines fully, she is awake, and she lacks the delicate and somewhat shocking organ on her pelvic region that so entices viewers of the Sleeping Hermaphrodite. However, the links to Roman copies of Greek sculptures was made evident in Bartolini’s work as well.

Rather than moving some fragile works into the exhibition proper, some of Bartolini’s plasters were kept in the Gipsoteca and were not moved into the temporary exhibition rooms. While it may not have been immediately clear that the two sections were connected, signage was present and the discussion of Bartolini continued in the Gipsoteca on wall labels and base labels, in a matching color scheme to the exhibition proper (the very nice, soft palette of light blue and periwinkle was used throughout by the designers), and this helped to connect these two separate areas of the exhibition. In the Gipsoteca, a very instructive video was presented so that visitors could see how sculptures were made in the period, and what role the plaster casts played in the creation of the marble and bronze sculptures. Many of the plasters in the Gipsoteca are “pointed” for transfer and thus provide good examples of this process.

The exhibition catalogue was available in Italian and English, but if one reads Italian, it would probably be better to purchase the Italian edition. The English translation, like most of the type that are published by museums in Italy, is not much of one. The translation is rough: for example, in the first essay by Maria Viginia Cardi, Bartolini the person is twice referred to as a “statuary.”[11] In the second essay one finds grammatically incorrect sentences like “the sisters had deserted the convent which was closed and subsequently, for a modest sum, given over to artists who did not have where to work.”[12] All original quotes are left in their original language (French or Italian) and are not translated at all. Basically the English reader has to overcome (and forgive) the errors in English and then slog through the primary quotes in two different foreign languages.

Once the reader is past these language issues, however, the quality of the writing, research and photography produced for the catalogue is very strong. It is a comprehensive text, including eleven essays covering all aspects of Bartolini’s life and work, including his training in France; his influences and his influence; his international clientele; and it includes an interesting section called “Ideas for Study” with three shorter essays on the Banca Elisiana (a mutual aid society that had its own “sculpture factory”), on Bartolini and the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence; and Bartolini’s subjects and photographic imagery. Every sculpture treated in the catalogue is given an extended, researched entry and is beautifully reproduced, mostly in color which greatly benefits scholars. In many cases a photograph of a marble sculpture is juxtaposed with its plaster model, making for some very interesting observations on the issue of transferring plaster to marble. Catalogue entries were written by an extensive team of important sculpture specialists from France and Italy, and the bibliography at the end of the text is extensive. The catalogue will no doubt remain the standard text on Bartolini for many years to come, and no sculpture library should be without it.

Ultimately Lorenzo Bartolini: Scultore del bello naturale beautifully and successfully represented Bartolini to a new audience. Bartolini’s influence was clearly widespread in Europe and significant to American artists studying in Europe, and can no longer be overlooked. Clearly the loss of the Gipsoteca would be appalling, as it remains the most significant, comprehensive and protected collections of original plasters by Italy’s foremost ottocento artist. The scholarly contribution of the exhibition catalogue to the study of nineteenth-century Purism makes this style ripe for deeper study. The exhibition was superbly organized and I was thankful to have experienced it during its extended run at the Accademia.

Caterina Y. Pierre, PhD

City University of New York at Kingsborough Community College

caterinapierre[at]yahoo.com

caterinapierre[at]kbcc.cuny.edu

Related Links

Official Press Release for the exhibition:

http://www.uffizi.firenze.it/en/mostre/mostra.php?t=4ebd73e0f1c3bce410001f6c

Review, Il Sole 24 Ore:

http://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/cultura/2011-05-31/firenze-ritrova-maestro-lorenzo-160353.shtml?uuid=AazCF9bD&;fromSearch

Digital Photo Gallery, Il Sole 24 Ore:

http://foto.ilsole24ore.com/SoleOnLine5/Cultura/Arte/2011/bartolini-mostra-firenze/bartolini-mostra-firenze_fotogallery.php?id=2

Review, Antiquari d’Italia: (Pages 7-8)

http://www.antiquariditalia.it/gazzetta/pdf/59/GA-59_I-2011-13-pp_56-83.pdf [.pdf]

[1] For an overview of the restoration of the Gipsoteca written soon after it was restored, see Franca Falletti, “Les fonds Bartolini et Pampaloni de Florence,” in La Sculpture du XIXe siècle, une mémoire retrouvée. Le fonds de sculpture (Paris: La Documentation francaise, 1986), 83–93.

[2] Franca Falleti, “Lorenzo Bartolini: An Introduction to the Exhibition,” in Franca Falletti, Silvestra Bietoletti, and Annarita Caputo, eds., Lorenzo Bartolini: Beauty and Truth in Marble (Florence and Milan: Giunti Editore S.p.A.), 12.

[3] Grégoire Extermann, “Napoléone Elisa with her dog,” cat. #13, in Lorenzo Bartolini: Beauty and Truth in Marble, 206–07.

[4] A good source on nineteenth-century Purism in Italy is Sandra Berresford, Italian Memorial Sculpture, 1820–1940: A Legacy of Love (London: Frances Lincoln Limited, 2004), 39 and 50.

[5] See Philip Ward-Jackson’s review of this exhibition in The Burlington Magazine CLIII: 1302 (September 2011): 631–32. Ward-Jackson does not use the term “Purism” in his review.

[6] Berresford, Italian Memorial Sculpture, 1820–1940: A Legacy of Love, 50.

[7] Grégoire Extermann, “Faith in God,” cat. #54, in Lorenzo Bartolini: Beauty and Truth in Marble, 310–13.

[8] For the links between Bartolini’s Faith in God and Vela’s Morning Prayer, see Filippo Morgantini, “L’Alfiere sardo di Vincenzo Vela: l’atre verista serve la cause italiana” in Quaderni del “Bobbio” Rivista di approfondimento culturale dell’I.I.S. “Norberto Bobbio” di Carignano 3 (2011): 98–101.

[9] Annarita Caputo, “The Greek Slave,” cat. #60, in Lorenzo Bartolini: Beauty and Truth in Marble, 330–31.

[10] Grégoire Extermann, “Demidoff Table or La Table aux Amours,” cat. #63, in Lorenzo Bartolini: Beauty and Truth in Marble, 336–39.

[11] Maria Virginia Cardi, “Lorenzo Bartolini in the Cultural and Political Atelier of Nineteenth-Century Florence,” in Lorenzo Bartolini: Beauty and Truth in Marble, 17.

[12] Maria Teresa Caracciolo, “‘Pour le coeur [...] Il est tout français’: Lorenzo Bartolini in France,” in Lorenzo Bartolini: Beauty and Truth in Marble, 29.