The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

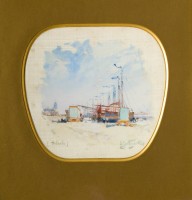

The entrance of a gouache on silk, Hollande (Holland) (fig. 1), by Nikolaĭ Nikolaevich Gritsenko (1856–1900) into the collection of the Katwijk Museum (inv. 5804) in the Netherlands is an opportunity to draw attention to this interesting but forgotten nineteenth-century marine painter and watercolorist.

Gritsenko’s gouache, which depicts the seaside at Katwijk facing south, dates from 1892. Measuring 23 cm by 24 cm, it is painted on silk, which is stretched on the back of a dull-gold mat with a fan-shaped opening, rimmed in bright gold. According to a description on the back, the mat was produced in Paris by framer Jean-Marie Boyer. Using delicate brushstrokes, Gritsenko brilliantly communicates the experience of a hot and muggy summer’s day at the beach. With masterly touches, he portrays bathing coaches and bluff-bowed fishing boats in characteristic detail. Individuals can be seen walking along the boats. Some have sought the shade. The blue sky reflects on the white of the tower and the roof of Saint Andrew’s Church in the distance.

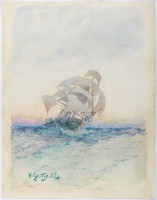

Closely related to the Katwijk gouache is a pen drawing from 1892 (fig. 2), now in the Scientific Research Museum of the Russian Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg. The drawing may be identified with a work that in the 1902 posthumous exhibition catalogue of the painter’s oeuvre is referred to as Éskiz” étoĭ kartinȳ (Sketch of this canvas).[1] “This canvas” refers to the preceding item in the catalogue, an oil painting with the title Katwyk-aan-See that Gritsenko sent to the Paris Salon of 1893, as is indicated in the catalogue. The whereabouts of this 1892 canvas are unknown. Gritsenko probably painted it in Katwijk. He later produced the pen-drawn copy of this canvas as a form of documentation.

An image of the Dutch shoreline set in a Parisian mat, painted by a Russian artist on a silk surface in the shape of a Far Eastern fan, the Katwijk gouache illustrates the international character of much of late nineteenth-century art. It also exemplifies Gritsenko himself, who, despite his origins in Russia’s heartland of Siberia and his service as an artist in the Russian navy, was a cosmopolitan artist par excellence. This cosmopolitanism did not always serve him well, particularly in the eyes of those Russian critics and collectors who favored authentic Russian art. Among the latter was the Moscow collector Pavel Tret’yakov, who was to become Gritsenko’s father-in-law. This article will place the Katwijk gouache in the context at once of late nineteenth-century cosmopolitanism and of Gritsenko’s own career, which was that of an artist torn between Europe and his homeland.

Nikolaĭ Nikolaevich Gritsenko was born on May 8, 1856 in the Siberian trading town of Kuznetsk, today’s city of Novokuznetsk. His father, Nikolaĭ Semënovich Gritsenko, was a country doctor. His mother, whose maiden name was Anna Fomina, was a midwife. From an early age the boy accompanied his father on his rounds, and so came into contact with the natural splendor of the Siberian plains, which would become part of his artistic inspiration later in life.[2]

Nikolaĭ’s first drawing-master, in the boys’ gymnasium in Tomsk, was Pavel Mikhaĭlovich Kosharov (1824–1902), a one-time pupil of Karl Bryullov and Ivan Aĭvazovski at the Arts Academy in Saint Petersburg. A traveler and explorer, Kosharov inspired in the adolescent Nikolaĭ a desire for adventure. After graduating from the gymnasium, when he was nineteen years old, Gritsenko traveled to Kronshtadt, a garrison town on the island of Kotlin in the Gulf of Finland, about thirty kilometers west of Saint Petersburg. There, he studied mechanics at the Emperor Nicholas I technical training school of the Russian navy from 1875 until 1880. Ultimately, Gritsenko would serve in the navy from 1880 until 1894.

Upon his graduation as a marine mechanics engineer in 1885, Gritsenko was approached by the admiralty. The naval authorities took an interest in his artistic talents and wanted him to become a painter in the service of the Russian navy. To this end, he enrolled in the Imperial Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts, studying art while performing his naval duties. From 1885 until 1887 he attended drawing classes as a vol’noprigodyashchiĭ (auditor), and took some informal lessons with the famous Russian landscape and marine painter Lev Feliksovich Lagorio (1828–1905). On Lagorio’s recommendation, the admiralty, in 1887, sent Gritsenko with a two-year scholarship to Paris to study with the Russian marine painter Alekseĭ Petrovich Bogolyubov (1824–96). The latter was living in the French capital as chief painter of the Russian navy.[3]

Bogolyubov was a respected painter of landscapes and seascapes, and an advocate of plein air painting. He knew everyone in the Parisian art world and for many years supported—professionally, socially, and financially—a host of young Russian artists who came to Paris to study under his supervision. He accompanied his pupils to expositions, private studios, and the annual Paris Salons to show them the new Western artistic ideas. At one time or another, Il’ya Repin, Vasiliĭ Polenov, Konstantin Savitskiĭ, Nikolaĭ Dmitriev-Orenburgskiĭ, and Aleksandr Beggrov all were part of his circle.[4] Because he held a central position in the Russian émigré community in Paris, Bogolyubov was perfectly equipped to introduce European painting to a younger generation of Russian artists, with many of whom he formed close friendships. Although Gritsenko had been instructed by the Russian navy to study with Bogolyubov, he decided to study as well with the reputed teacher Fernand Cormon (1845–1924).

Gritsenko’s time in Paris lasted with some interruptions for more than ten years, from 1887 until 1898, during which time he produced a steady output of art works for the Paris Salon. Painted en plein air, with loose brushstrokes, these included seascapes and views of the harbors of Le Havre, Marseille, Le Tréport, and Kronshtadt, as well as views of Moscow. Gritsenko also painted landscapes, beach scenes, and ships, and worked as an illustrator for the Parisian magazines L’Artiste and L’Illustration and later for Russian magazines as well.[5]

From July 1890 to August 1891, navy officer Gritsenko traveled around the Eurasian continent on board the Russian frigate Pamyat Azova (Memory of Azov) in the company of the Russian heir to the throne, Tsesarevich Nikolaĭ Aleksandrovich, the later Tsar Nicholas II. Gritsenko painted more than three hundred watercolors on the trip. They are scenes of triumphant entries into ports, and depictions of monuments and glamorous costumes.[6] These works were exhibited in 1892 in the Parisian art gallery of art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831–1922). It was Gritsenko’s first large solo exhibition. Seven works came into the possession of the later Tsar. Two were bought by author-publisher and crew member Esper Ukhtomskiĭ (1861–1921).[7] Some two hundred drawings were later used for the production of an album that was offered to Nicholas II as a reminder of his Eurasian trip. Also, two hundred photographs were taken by crew member Vladimir Mendeleev (1865–98). The whereabouts of the album or the photos are not known.[8]

After his return from the trip with Tsesarevich Nikolaĭ Aleksandrovich, Gritsenko worked in the south of France, Normandy, and Brittany, and traveled to Italy and Holland. His two trips to Katwijk date from this period. In the course of the second half of the nineteenth century, this North Sea fishing village had developed into a fashionable artists’ colony visited by painters from all over the world, who were attracted at once by the village’s good accommodations and its picturesque subject matter of seashore, fisher-folk in their traditional costumes, and traditional fishing boats with broad flat bows painted in muted colors.[9] In the village’s heyday, from about 1880 to 1910, more than five hundred artists worked here. In 1898 alone, 61 of the 878 visiting bathers were artists.[10]

Gritsenko worked in Katwijk for two summers, in 1889 and again in 1892. Both times he traveled to Holland from Paris, where he studied with Bogolyubov. His stay in 1889 was a most prolific one. The 1902 exhibition catalogue lists under the heading G. Katwyk-aan-See. Gollandiya (T. [Town] Katwijk-aan-zee. Holland) some twenty drawings.[11] During his second stay, in 1892, he produced the canvas Katwyk-aan-See and the pen-drawing Éskiz” étoĭ kartinȳ (Sketch of this canvas).[12]

In Paris, in the early 1890s, Gritsenko befriended the Russian family Ziloti. Vera Pavlovna Ziloti (1866–1940) and her husband, the pianist Aleksandr Il’ich Ziloti (1863–1945), were touring through Europe. Between 1892 and 1894, they lived in the French capital with their children.[13] Vera Pavlovna Ziloti was the daughter of the Moscow textile industrialist, art collector, and patron of the indigenous Russian school of painting Pavel Mikhaĭlovich Tret’yakov (1832–98). It is in the family circle of the Zilotis that Gritsenko makes his acquaintance with his future wife, Lyubov Pavlovna Tret’yakova (1870–1928), who was Vera Pavlovna’s sister. Lyubov had come to help her sister, who was expecting her fourth child.[14]

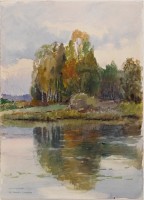

Lyubov and Vera were the daughters of Pavel Tret’yakov, founder of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. Although he was a collector and patron of the arts, Tret’yakov wanted his daughters to marry men with a commercial talent rather than artists or musicians, because he did not think much of their moral qualities.[15] In November 1893, Gritsenko was introduced to his future father-in-law. The latter’s impression of Gritsenko was anything but positive. Lyubov wrote to her sister Aleksandra Botkina that “father made his acquaintance, and pulled a face. He only said that he was old and ugly.”[16] Yet, as time went on, Tret’yakov’s affection for Gritsenko would grow (fig. 3) and the couple would marry in Russia on June 10, 1894.[17] The artist was 38; his wife 24.

After the marriage, Gritsenko was released from naval service and was appointed by the admiralty as Painter of the Russian Navy. A new period in his career began, marked by oil-painting commissions from the navy and trips to distant corners of the Russian Empire to produce documentary watercolors for the Imperial Russian Geographical Society.[18]

It would seem that Gritsenko’s marriage to the daughter of Russia’s foremost collector of contemporary Russian art might have been advantageous for the artist. A year before their first contact, Pavel Tret’yakov had donated his collection of almost two thousand works of art to the city of Moscow. Russia’s primary promoter of contemporary Russian art, he loved the work of the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers), a cooperative of artists who focused on the many-sided aspects of life in Russia in paintings often critical of social and economic inequalities and injustices, but also showing the beauty of folk life and the Russian landscape.

Gritsenko’s art represented a trend in Russia that ran counter to the indigenous Russian school of painting of which his father-in-law had been a most ardent advocate. At the same time that the Peredvizhniki achieved success in Russia, new and exciting art ideas had entered the country from the West. Embracing these ideas offered opportunities for Russian artists to gain Western recognition or even world-wide fame, and make money in the West, where the art market was more developed than in Russia. Indeed, these were the objectives of many Russian painters who crowded the art scene in Paris. Gritsenko’s stance in this East-West debate leaned toward the West. Granted, in the watercolors that he produced for the Imperial Russian Geographic Society, he showed that he was a brilliant depicter of the vast Siberian wilderness, and in his own words, he “insanely much loved that Russian school [of painting].”[19] But he preferred to achieve an international rather than a Russian reputation and ardently hoped to become a successful European artist.

Regardless of his dislike for Western-style Russian painting, Tret’yakov paid serious attention to Gritsenko’s work, and certainly appreciated some of it. But he did not hesitate to point out flaws where he saw them. Referring to L’Entreprenante à Toulon, a painting Gritsenko had entered into the Paris Salon of 1895, he wrote,

The painting by Nikolaĭ Nikolaevich is very boring: it is not even a painting, but rather a sketch, . . . and, moreover, a sketch should not only be excellently executed, but must also be interesting in its subject matter—and what can be more uninteresting than a ship being built?[20]

But Tret’yakov also purchased work from Gritsenko. In 1893 he bought a painting for three hundred rubles. The artist was delighted. In December of that year he wrote from Paris,

Dear Mr. Pavel Mikhaĭlovich! I am extremely grateful that you did me the honor of purchasing my painting and I hope that later I will deserve your attention with work more serious than this simple preliminary model study.[21]

In the summer of 1896, Nikolaĭ Gritsenko traveled with his wife and her youngest sister Mariya to the south of Russia. This was a tour of duty for the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, of which Gritsenko was a member. In less than a month, they covered a distance of over 4,000 miles by train, by boat, and on horseback. Gritsenko produced numerous watercolors and oil paintings. A few months later, from December 15 to 31, 1896, eighty-three watercolors and twelve paintings were displayed in Gritsenko’s second one-man exhibition at Paul Durand-Ruel’s gallery. The critic François Thiébault-Sisson wrote the preface for the catalogue in which he praised the “colorful” works for being “as lively as they are delicate, as impertinent as they are subtle.”[22] In the announcement for the exhibition in a French art newspaper, the author of the article (O. F.) wrote,

A dozen oil paintings of a beautiful and strong execution, of a clear and bright color; but it is especially by his watercolors that Mr. Gritsenko demonstrates he is a skilled as well as a genuine artist. . . . The artist excels especially in giving the various aspects of the sea.[23]

After Bogolyubov’s death in 1896, Gritsenko was appointed Chief Painter of the Russian Navy. Commissioned by the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, he traveled to the Volga area, Caucasus, Crimea, and Siberia (Lake Baikal, Tomsk).[24] More than seventy watercolors, drawings, studies, and sketches with Siberian subjects, and twenty watercolors of Tomsk, made during this trip, are now kept at the Scientific Research Museum of the Russian Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg.

In 1898, Nikolaĭ Gritsenko fell ill with what later turned out to be tuberculosis. His medical condition forced him to relocate to a warmer climate, and the couple returned to France. He died on December 8, 1900 in Menton on the French Riviera.[25] He was 44 years of age. That same day he was awarded the highest French decoration—the medal and title of Chevalier (Knight) of the Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur.[26] He was buried in the Russian Orthodox cemetery in Menton, France.

After her husband’s death, Lyubov organized, in December 1902, an exhibition of his work in the hall of the Imperial Society for the Promotion of the Arts in Saint Petersburg.[27] The walls were crammed with paintings, watercolors, drawings, and studies. The catalogue lists no fewer than 805 items,[28] some of which are reproduced in figs. 4–7. The event did not go unnoticed. In a 1902 letter to Il’ya Ostroukhov, who was director of the Tretyakov Gallery at the time, the celebrated painter Il’ya Repin expressed his appreciation for his colleague Gritsenko. He wrote,

A talented person, intelligent, with a love of the arts. He puts his whole soul into understanding contemporary Parisian art. . . . The whiteness of the paint, the lilac of Impressionism, the complexity of the decorator in the composition of the paintings, the dashing brushwork of the master, the cheerful tone of the paints, etc.—he has all that.[29]

Repin’s quotation brings us back to the small watercolor in the Katwijk Museum, which, despite its modest format, has all the characteristics Repin mentions and marks the work of an artist who was more French than Russian. “Gritsenko, quoique Russe, est des nôtres” (“Gritsenko, although Russian, is one of us”), wrote the French art critic Thiébault-Sisson in the Paris daily Le Temps in 1896.[30] Yet, Gritsenko never stopped loving his motherland. Many of his works depict the natural or urban scenery of Russia, and these works are more in line with Russian art, resembling the work of such contemporary Russian landscapists as his teacher Bogolyubov. Il’ya Repin recognized this and in the same letter to Ostroukhov he wrote,

I can write a whole treatise on the sacrifices [Gritsenko made] to imitate the West. . . . And all of that is “in a lot of things unbearable.” But, nevertheless, sometimes this talented person, when he denied his daily wage in the West, did outstanding, in every aspect artistic things.[31]

Jeroen van der Boon

jeroenvanderboon[at]ziggo.nl

Parts of the information in this article were published in another form in the Russian journal Nashe Nasledie: Jeroen van der Boon, “Zhivopisets-marinist Nikolaĭ Gritsenko,” Nashe Nasledie 122 (2017).

This article is part of my broader research on nineteenth-century Russian marine painters who visited my hometown, Katwijk aan Zee, Netherlands, around 1900. Transliteration of Russian names and words in the text, except for familiar Russian names of persons and places (e.g., Nicholas I; Saint Petersburg) is according to the British Standards Institution. See Terence Wade and Michael Holman, A Comprehensive Russian Grammar, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000), 1–2. All translations are by the author.

[1] Posmertnaya Vȳstavka kartin, étyudov i akvareleĭ Nikolaya Nikolaevicha Gritsenko [Posthumous exhibition of paintings, studies and watercolors of Nikolaĭ Nikolaevich Gritsenko], exh. cat. (Saint Petersburg: Tovarishchestvo Khudozhestvennoĭ Pechati, 1902), 12.

[2] Biographical background information on Gritsenko from Putevoditel’ po rukopisnȳm fondam Gosudarstvennoĭ Tret’yakovskoĭ Galerei [Guide to the manuscript storage of the State Tretyakov Gallery] (Moscow: Izdatel’stvo “SkanRus,” 2005), 30, 35, 40, 64, 65, 192, 258, 260.

[3] Elena Terkel’, “Korabl’ moĭ plȳvët ostorozhno . . . Nikolaĭ Gritsenko” [“My ship sails cautious . . . Nikolaĭ Gritsenko”], Russkoe Iskusstvo, no. 1 (2008): 98–105 passim.

[4] Rosalind P. Blakesley and Susan Emily Reid, eds., Russian Art and the West: A Century of Dialogue in Painting, Architecture, and the Decorative Arts (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2007), 21–44.

[5] In the decade that Gritsenko lived in the French capital, the painter went through six different addresses. In 1887, he lived in Montmartre; in 1888 and 1890, at 73 Boulevard de Clichy; in 1891, in quartier Saint-Georges at 30 Rue Fontaine; in 1892 and 1893, at 11 Boulevard de Clichy; in 1894, at 23 Boulevard Gouvion Saint-Cyr; from 1895 to 1897, at 5 Rue Clément-Marot; and from 1898 to 1900, at 35 Avenue d’Eylau. Data from Pierre Sanchez and Xavier Seydoux, Les catalogues des Salons (Paris: L’Échelle de Jacob, 1999–2011), 15:1196; 16:759, 807; 17:863, 873; and 18:953–954.

[6] BSÉ (Bol’shaya Sovetskaya Éntsiklopediya), s.v. “Gritsenko.” The State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg preserves 296 watercolors by Gritsenko, of which 274 were completed during the Eurasian trip of 1890/1891. Letter to the author from Evgeniya Petrova, deputy director of scientific activities, June 28, 2016.

[7] Posmertnaya Vȳstavka Nikolaya Gritsenko, 10–11.

[8] Terkel’, “Korabl’ plȳvët,” 99.

[9] Annette Stott, preface to Dutch Utopia: American Artists in Holland, 1880–1914, ed. Annette Stott (Savannah: Telfair Books, 2009), 17.

[10] These figures come from visitors’ data that providers of accommodations (hotels, private lodgings) had to produce. See Nina Lübbren, Rural Artists’ Colonies in Europe, 1870–1910 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001), 170.

[11] Posmertnaya Vȳstavka Nikolaya Gritsenko, 9–10. Titles of the works (whereabouts unknown): Sel’dyanoĭ bot [Herring boat]; Sel’dyanoĭ bot [Herring boat]; Étyud bota [Study of a boat]; Étyud bota [Study of a boat]; Bot na peskě [Boat on the sands]; Bot na peskě [Boat on the sands]; Priboĭ [Breakers]; Priboĭ [Breakers]; Bot na peskě [Boat on the sands]; V otliv [At low tide]; Marina [Seascape]; Morskiya kupan’ya [Swim in the sea]; Utro[Morning]; Dyunȳ [Dunes]; Vecher [Evening]; V otliv [At low tide]; Pod solntsem [In the sun]; V g. Dordrecht. Gollandiya [In the town of Dordrecht. Holland]; Russkiĭ voennȳĭ kater [Russian naval boat]; Na minonostsě [On a torpedo boat]; Dama s binoklem [Lady with binoculars]; Raznȳe étyudȳ [Different studies].

[12] Posmertnaya Vȳstavka Nikolaya Gritsenko, 12.

[13] L. M. Kutateladze and L. N. Raaben, eds., Aleksandr Il’ich Ziloti 1863–1945, vospominaniya i pis’ma [Aleksandr Il’ich Ziloti 1863–1945, memoirs and letters] (Leningrad: Gosudarstvennyĭ Muzeĭ Istorii, 1963), 331.

[14] Lyubov Pavlovna Tret’yakova (1870–1928) was the daughter of Pavel Tret’yakov (1832–98) and his wife Vera Nikolaevna Mamontova (1844–99), and the third oldest of four. The four sisters differed little in age. Vera Tret’yakova was the oldest. Aleksandra followed, then Lyubov, and the youngest was Mariya. Vera Pavlovna Tret’yakova (1866–1940) married the musician Aleksandr Il’ich Ziloti (1863–1945) in 1887. Aleksandra Pavlovna Tret’yakova (1867–1959) married the physician and art collector Sergeĭ Sergeevich Botkin (1859–1911) in 1890. Mariya Pavlovna Tret’yakova (1875–1952) also married a Botkin: Aleksandr Sergeevich Botkin (1866–1936), sailor, physician, inventor, and explorer.

[15] Kutateladze and Raaben, Aleksandr Il’ich Ziloti 1863–1945, 328.

[16] “папа с ним познакомился, покривился. Только сказал, что стар и некрасив.” O. A. Belousova and G. G. Vashchenkova, “Iz istorii sem’i Gritsenko” [“From the history of the Gritsenko family”], Nauka i obrazovanie, Materialȳ Vserossiĭskoĭ nauchnoĭ konferentsii, paper presented at the All-Russian Scientific Conference “Science and Education,” Belovo, 2004.

[17] Wedding Invitation, Source collection and file number F. 66, Ed. khr. 235, Manuscript Department, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

[18] Terkel’, “Korabl’ plȳvët,” 100. See also Belousova and Vashchenkova, “Iz istorii sem’i Gritsenko.”

[19] Nikolaĭ Gritsenko to Aleksandra Botkina, May 6, 1900, Source collection and file number F. 48, Ed. khr. 4174, Manuscript Department, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

[20] “Картина Николая Николаевича очень скучна: это не картина даже, а этюд, . . . этюд же, кроме того, что должен быть виртуозно написан, но и по содержанию должен быть интересен, а что может быть неинтереснее строящегося корабля?” Terkel’, “Korabl’ plȳvët,” 100.

[21] “Милостивый Государь Павел Михайлович! Чрезвычайно благодарю Вас, что почтили меня покупкою моей картины; надеюсь, что впоследствии заслужу Ваше внимание более серьёзными моими работами, чем этот простой этюд с натуры.” Nikolaĭ Gritsenko to Pavel Tret’yakov, December 1, 1893, Source collection and file number F. 1, Ed. khr. 1301, Manuscript Department, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

[22] Thiébault Sisson, preface to 2me exposition d’aquarelles et d’études de N. Gritsenko, exh. cat. (Paris: Galeries Durand-Ruel, 1896), 1–15.

[23] “Une douzaine de peintures à l’huile d’une belle et solide exécution, d’une couleur claire et lumineuse; mais c’est surtout par ses aquarelles que M. Gritsenko se révèle à nous comme un artiste habile autant que sincère. . . . L’artiste excelle surtout à rendre les différents aspects de la mer.” O. F., “Tableaux et aquarelles de M. Gritsenko,” Chroniques des Arts et de la Curiosité, December 19, 1896, 374.

[24] Terkel’, “Korabl’ plȳvët,” 102.

[25] Ibid., 103.

[26] “Nouvelles du jour,” Le Temps, December 13, 1900, 3.

[27] Many of these works cannot be traced. Sometime after his death, his daughter Marina became the treasurer of her father’s artistic legacy, but her poor living conditions did not enable her to safeguard all of her father’s work. A part was neglected; another part was lost in the Leningrad floods of the 1920s. Marina then decided to allocate the rest of the works. Some works were bequeathed, others were sold. Some works ended up in the Tretyakov Gallery, which, at present, possesses 85 drawings and 7 paintings. In 1948, Marina sold another part of her father’s works to the Academy of Arts of the USSR (the present Russian Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg).

[28] Posmertnaya Vȳstavka Nikolaya Gritsenko, 3–36.

[29] “Талантливый человек, умный, с любовью к искусству. Кладет всю свою душу, чтобы постичь современное парижское искусство. . . . Белизну красок, лиловость импрессионичества, сложность декоратора в композиции картин, размашистый мазок мастера, веселый тон красок и т. д.—все у него есть.” Il’ya Repin to Il’ya Ostroukhov, November 21, 1902, quoted in Il’ya Repin, Pis’ma k khudozhnikam i khudozhestvennȳm deyatelyam [Letters to artists and art officials] (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1952), 155.

[30] Thiébault-Sisson, “Un aquarelliste russe N. Gritsenko” Au jour le jour, Le Temps, December 18, 1896, 2.

[31] “Можно написать целый трактат о жертвах обезьяннического подражания Западу. . . . И все это—‘в. большом количестве нестерпимая’. И, однакоже, иногда этот талантливый человек, когда забывался от своей поденщины на Западе, делал прекрасные, вполне художественные вещи.” Repin, Pis’ma k khudozhnikam, 155.