The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

In late 1849, Massachusetts native George Fuller (1822–84) traveled throughout the Deep South in pursuit of portrait commissions.[1] Like many of his northern contemporaries, Fuller sought a receptive and less competitive climate below the Mason-Dixon Line. The artist’s journey placed him directly in the midst of a region addicted to the institution of slavery, and while it may not have been his intention to observe astutely the lives of human chattel, Fuller was increasingly aware of their plight and recorded his observations in a sketch diary. Fuller’s drawings and subsequent commentary revealed neither his political inclinations about the “great divide” that was gripping the nation nor his moral position on the subject. This was, however, his third trip to the region, and while his sketches remained dignified depictions of black plantation life, his words reflected growing concern over certain “rituals” conducted in the South.

One of these rituals, a slave auction involving a beautiful quadroon, affected him profoundly. Fuller had witnessed slave auctions before, but the sight of men bidding over a nearly white slave like a farm animal caused him to write:

Who is this girl with eyes large and black? The blood of the white and dark races is at enmity in her veins—the former predominated. About ¾ white says one dealer. Three fourths blessed, a fraction accursed. She is under thy feet, white man. . . . Is she not your sister? . . . She impresses me with sadness! The pensive expression of her finely formed mouth and her drooping eyes seemed to ask for sympathy. . . . Now she looks up, now her eyes fall before the gaze of those who are but calculating her charms or serviceable qualities. . . . Oh, is beauty so cheap?[2]

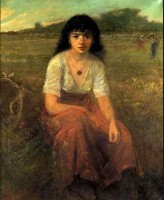

Fuller never translated his disturbing encounter into a narrative painting of a slave auction, but instead internalized the image of the helpless girl for years. In 1880, he purged that memory by painting The Quadroon (fig. 1), a scene of a brooding, fair-complexioned young slave woman staring out beyond the confines of the canvas as darker-skinned slaves labor behind her in a cotton field. Although Fuller made no direct commentary or judgment about the institution of slavery in the work, he clearly offered an opinion as to the quandary women like her faced daily—she remains an isolated figure who does not fully fit in either the white or black race. Instead, he depicts her as one in a struggle to claim a racial identity and as the ultimate “victim” of America’s ambivalence over her societal placement.

Unfortunately, Fuller missed the opportunity to add a dramatic chapter to the visual chronicling of the slave-selling experience, but by the time of the painting’s creation, slavery was fifteen years in the past and the immediate impact of the social and moral damnation of the practice was negligible. Still, he revisited an issue, “white slavery,” that served as a potent contrivance in the abolitionist’s agenda.[3]

This paper examines two paintings from the antebellum period, The Slave Market (fig. 2) by an anonymous artist and The Freedom Ring (fig. 3) by Eastman Johnson (1824–1906), which involve the purchase of nearly white female slaves, and delineates the motivation for presenting these images before the public. I address and clarify the practice of “white slavery” in America and show how abolitionists adapted the growing visibility of “white slaves” as a means of expression that not only widely exposed the plight of those who looked as if they were part of the dominant culture yet were treated as wholly subordinate, but also provided them with a source for images that proved to be an effective propaganda tool in support of their ideals.

Although the focus of this paper is on two paintings that unmistakably demonstrate the thematic power of addressing the institution of slavery through the lens of perceived whiteness, it must be understood that the presence of African Americans, slave or free, was common in art of the nineteenth century.[4] However, paintings depicting slaves being sold either in private quarters or in open public auctions apparently had no widespread appeal and offered little financial incentive for most nineteenth-century artists. Southern artists probably viewed the subject as a mundane part of everyday life, a simple business transaction that held no interest for the art-buying public. Any southerner inclined to absorb the visual stimulation inherent in a slave auction would not have to travel a great distance to witness such a spectacle. Even one potential source of clientele, those who were involved in the exchange of money for human beings, likely wished to distance themselves from dehumanizing imagery once they returned to the comforts of their homes. Furthermore, paintings of slaves and slave auctions simply had no place in southern art collections, especially after paintings of slaves at auction began to take on decidedly abolitionists overtones. Art historian Kirk Savage noted:

The power of abolitionist imagery was so strong that it made it very difficult for those sympathetic to slavery to create any convincing alternative imagery of the institution. In fact, it was problematic for the proslavery forces to make any visual representation of their system at all. By the mid-nineteenth century much of the traditional imagery of slavery had been appropriated by abolitionists.[5]

Thus, any imagery of slaves in distressed situations—chained, laboring, or on the auction block—inevitably became a potent tool of abolitionists in advancing their cause through visual manipulation of real or perceived plights. Therefore, it is not surprising that surviving paintings of slaves being bought and sold, although not numerous based on extant examples, come from northern artists with ties to the abolitionist movement.[6]

White Slaves: A Real and Tragic Presence

George Fuller’s encounter with the young quadroon says much about the impact those of mixed race were having on the antislavery debate. The 1860 census records more than 588,000 mulattoes in America.[7] Their growing numbers, raising from 11.15 per cent of the total black population in 1850 to 13.35 percent in 1860, indicates a rapidly increasing presence that likely attracted more public attention, North and South, and caused greater scrutiny over the “color parameters” of chattel slavery. If imported “pure” African slaves were acceptable to many Americans based on skin color and their perceived inferior qualities—and thus destined for perpetual servitude—mulattoes created uneasy quandaries as to their ultimate assignment and acceptance in antebellum society. Their presence in the South, in particular, often complicated matters of where racial lines should be drawn and accelerated slavery toward a system based on acute racial classification. The “one-drop rule,” though widely accepted throughout America, often blurred upon scrutiny of certain “persons of color,” and numerous reports surfaced from the South describing slaves indistinguishable from whites. As mulattoes begot quadroons and as quadroons begot octoroons, the defense of slave trading grew increasingly problematic. If the peculiar institution started in America as a practical and profitable model for the organization of farm labor, the ascendance of trafficking in “white slaves” transformed it, in large part, into a business of pleasure for profit. As a result, the economic power inherent in the lucrative business end of slavery, always driven by supply and demand, often dictated that there were no boundaries of whiteness that were off limits, and near-white concubines were as easily commodified as were prime field hands and domestic servants. The buyers of these concubines, given the high prices paid for them, likely insisted that “whiter was better” on the auction block and back on the plantation, and that the “one-drop rule” be applied literally.

If southerners involved in the slave trade wished to keep the increasing number of “white slaves” a regional secret, it inevitably failed. Astonished foreign visitors to the South, dumfounded visiting northerners, descriptive newspaper announcements seeking the return of runaways, sensationalized abolitionist accounts, and stories and stage performances centered on the “tragic” mulatto or octoroon all drew attention to the practice of selling slaves with light complexions.[8] The issue of “white slavery” increasingly became an enormous burden on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. Fugitive slaves light enough to pass for white could easily blend into the mainstream in the North and be hard to identify by bounty hunters. Their secretive blending into northern white society also raised concerns for those for whom the “comfort” of racial purity rested solely on unquestionable knowledge of family background. Some auctions involving the sale of “white slaves” were followed by reports of disruptions caused by outraged observers who drew distinct color lines during the process. In some instances, accounts circulated that even pure whites fell victim to enslavers who kidnapped them and placed them on the auction block with the claim that their bloodline was “tainted.”[9]

The rise in published accounts documenting “white slaves” increased public awareness of this growing trend in America and abroad. Reverend Calvin Fairbank, for example, wrote that while in Lexington, Kentucky he observed a woman sold at auction who was “one of the most beautiful and exquisite young girls one could expect to find in freedom or slavery . . . being only one sixty-fourth African.”[10] Reverend Philo Tower, a New Englander on a visit to New Orleans, saw a young slave woman at auction who mesmerized him. He noted she was

one of the most beautiful, I think, I ever saw, aged from sixteen to twenty. Though thinly and cheaply dressed, none could be insensible to her beauty. She was much whiter than many, nay, than most of the Anglo-Saxon ladies, one medium size, well developed, beautiful black hair and sparkling eyes that pierced wherever they darted. . . . Rudely drawing the covering from her neck and shoulders, . . . [the auctioneer] exhibited a bust as plump and purely white as the snow-tinged image of Venus.[11]

Tower went on to say she sold for two thousand dollars. He also witnessed, immediately after this auction, the selling of a woman he described as “a rather darkish mulatto woman” and “her daughter nearly white.”[12] He noted that the auctioneer made an effort to sell the two together, but, in the end, they went to separate bidders.[13]

Fredrika Bremer, a Swedish novelist and humanitarian, wrote that on a trip to Georgia around 1850, she witnessed a slave auction where “many of these children were fair mulattoes and some of them very pretty. One young girl of twelve was so white that I should have supposed her to belong to the white race; her features, too, were also those of whites. The slave-keeper told us that the day before, another girl, still fairer and handsomer, had been sold for fifteen hundred dollars.”[14]

During his travels in the American south in 1837 and 1838, Captain Frederick Marryat, a British naval officer, wrote of his encounter with a “white slave” in Louisville, Kentucky. He said, “I saw a girl, about twelve years old, carrying a child; and, aware that in a slave State the circumstance of white people hiring themselves out to service is almost unknown, I inquired of her if she were a slave. To my astonishment, she replied in the affirmative. She was as fair as snow, and it was impossible to detect any admixture of blood from her appearance.”[15]

Even the slave narrative of William Wells Brown, the abolitionist, author, historian, and son of a white plantation owner and his black slave concubine, contained a reference to a “white slave” he encountered in Hannibal, Missouri. Wells wrote:

A few weeks after, on our downward passage, the boat took on board, at Hannibal, a drove of slaves, bound for the New Orleans market. They numbered from fifty to sixty, consisting of men and women from eighteen to forty years of age. . . . There was, however, one in this gang that attracted the attention of the passengers and crew. It was a beautiful girl, apparently about twenty years of age, perfectly white, with straight light hair and blue eyes. But it was not the whiteness of her skin that created such a sensation among those who gazed upon her—it was her almost unparalleled beauty. She had been on the boat but a short time, before the attention of all the passengers, including the ladies, had been called to her, and the common topic of conversation was about the beautiful slave- girl. She was not in chains. The man who claimed this article of human merchandise was a Mr. Walker—a well-known slave-trader, residing in St. Louis. There was a general anxiety among the passengers and crew to learn the history of the girl. Her master kept close by her side, and it would have been considered impudent for any of the passengers to have spoken to her, and the crew were not allowed to have any conversation with them. When we reached St. Louis, the slaves were removed to a boat bound for New Orleans, and the history of the beautiful slave-girl remained a mystery.[16]

Finally, Edward Sullivan, an Englishman visiting New Orleans, shared Philo Tower’s curiosity over the sale of a “white slave.” He wrote, “I have seen slaves, men and women, sold in New Orleans, who were very nearly as white as myself. . . . Although it is not actually worse to buy or sell a man or woman who is nearly white than it is to sell one some shades darker, yet there is something in it more revolting to one’s feelings.”[17]

These accounts, and scores of others, left no doubt that “white slavery” not only existed in the South, but was a common and thriving state of affairs.[18] As abolitionist activities expanded in the North, knowledge of the practice became a powerful tool to fuel their crusade.[19] William Jay, an abolitionist whom Frederick Douglass called “our wise counselor, our fine friend, and our liberal benefactor,” was aware of the situation and linked it to the abolitionist cause. He stated, “People at the North are disposed to be incredulous when they hear of white slaves at the South: and yet a little reflection would convince them not only that there must be such slaves under the present system, but that in the process of time a large proportion of the slaves must be as white as their masters.”[20]

The Displaying of Near-White Bodies to Advance a Cause

In order for visual representations of “white slaves” to attain their intended impact among curious or concerned northerners, it was necessary for some abolitionist-inspired artists to draw motivation from tragic mulatto, quadroon, and octoroon elements commonly found in widely circulated literary sources. Born largely from tales of fugitive slaves, in particular in the form of slave narratives and novels detailing plantation life, images produced by abolitionists served to provide visually verifiable evidence of the atrocities inherent in the system and, ultimately, undermine it.[21] For that reason, these literary formats were powerful and radical forms of antislavery propaganda that exposed the institution as a malevolent societal construct. Yet the majority of published slave narratives came from a male perspective as many supporters and readers of this literature surrendered to gender biases galvanized by the dominant perception of women—black or white—strictly serving in domestic and subservient roles.[22] However, interest in the plight of near-white female slaves—most often portrayed as helpless victims of sexual predators doomed to meet tragic fates because of their “tainted” blood—gradually grew as news of their existence spread northward and allowed for them to attain a prominent position in abolitionist discourse. In fact, prominent abolitionist Lydia Maria Child practically invented the literary character type of the tragic mixed-race female in 1842 with the short story, The Quadroons. In addition, the popularity of the exalted role bestowed upon the runaway mulatto Eliza Harris in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), and the tragically torn and conflicted mixed-race Zoe found in Dion Boucicault’s immensely popular play, The Octoroon (1859), pushed the plight of near-white slaves to new heights within the dominant culture. Therefore, it is not surprising that around this period images of “white slaves” began to appear in American paintings.

As a precursor to paintings of “white slaves,” abolitionists circulated photographs in the North that depicted near-white slaves that proved to be an extremely effective device in advancing their cause.[23] One of the earliest of these images was that of Mary Mildred Botts, a seven-year-old child from Virginia who showed no outward appearance of black ancestry (fig. 4).[24] Her “discovery” in 1855 attracted the attention of Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts who, in turn, used her in his appeal for widespread emancipation. He drafted a letter that the Boston Telegraph and the New York Daily Times printed in which he drew comparisons between Botts and the fictional protagonist of Mary Hayden Pike’s novel Ida May (1854). In that work, considered by many to be a close rival to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Ida May appears as a young white girl who is kidnapped from Pennsylvania and sold into slavery. Sumner wrote of Botts, “She is bright and intelligent—another Ida May. I think her presence among us [in Boston] will be more effective than any speech I can make.”[25] As will be shown, similar photographs grew steadily in distribution in the North and played a large part in the translation of “white slave” imagery to oil and canvas.

As interest in “white slaves” gained momentum in abolitionist circles and American popular culture, the auction block provided artists with the perfect setting to maximize reactions of sympathy and indignation from their audiences by graphically depicting the seamy underpinnings of the “flesh for sale” business. Many abolitionists reasoned that most northerners were geographically, economically, and emotionally detached from slavery and, therefore, less motivated to join or support their cause. Consequently, the use of fugitive slaves as authors and lecturers proved an effective strategy in awakening the population in the North from its slumber over the racial divide that accelerated the country toward civil war. Eventually, artists added a visual dimension to the debate over emancipation and created images that made visible antislavery rhetoric.

Slave auctions, in fact, presented African Americans at one of their most helpless moments. If abolitionists wanted to convince visually a skeptical northern population of atrocities committed against southern slaves, they had to deliver their message with maximum impact, and depictions of fair-skinned children and young women facing the auction block fulfilled that requirement. By presenting slavery through the lens of women who resembled white northerner’s sisters, daughters, close relatives, or neighbors, abolitionists and abolitionist-minded artists found a commanding platform to assist in dismantling bondage in the South.

Art historian Albert Boime said of this clear and easily understood connection,

The “tragic octoroon” became a stereotyped heroine especially in pre-Civil War fiction. Although the plots changed, invariably the beautiful octoroon is a daughter of a well-established Southern plantation owner and his mulatto mistress and is raised and educated as white. Through negligence or indifference in obtaining proper papers, she is sold into slavery after the death of her father. Her degradation reaches a dramatic culmination at the slave auction.[26]

In addition, the strong linkage between the visual and the literary in paintings of slave auctions that featured near-white women also provided knowledgeable viewers with a unique insight into “morally corrupt” southerners. Art historian Sarah Burns clearly defined the strong bond shared between the image and the printed word as exemplified in George Fuller’s previously mentioned The Quadroon. She stated:

The sentimental appeal of Fuller’s The Quadroon has other associations as well. Although she was painted in 1880, her counterparts are to be found in the anti-slavery literature of the 1840s and 1850s. A number of abolitionist works of fiction featured as heroine an exotically beautiful quadroon or octoroon, the tainted but blameless victim of the Southern caste system. Whether the outcome of such tales was happy or tragic, the quadroon was invariably subjected to terrible sufferings and indignities, against which she was powerless. Because of her beauty, her helplessness, and her near-whiteness, the quadroon appeared as a highly pathetic figure, more so, perhaps than the slave of pure African ancestry.[27]

The Selling of a Fancy Gal

It is the dilemma of racial ambiguity and societal status that frames The Slave Market, a painting that unmistakably puts the practice of dealing in “white slaves” squarely before the viewing public. The anonymity of the artist and lack of any known recorded response to the painting precludes knowing the full background and motivation that led to its creation.[28] Yet the rich antislavery imagery composed as a series of individual slave-related vignettes unified by the centrally located auction process clearly shares much in common with printed melodramatic descriptions of the period. And while the artist depicts this auction as an idealized, almost tranquil accounting, it nevertheless, upon careful scrutiny, reveals a variety of appalling activities conducted by villainous slave dealers, thus reinforcing its importance as a major work of liberation appeal.

While unpacking the entire meaning of The Slave Auction is hampered somewhat by the lack of detailed information as to its construction and ultimate intention, the artist nonetheless carefully weaves an intuitive narrative that surely reflects a decided antislavery agenda that lessens the need for pure speculation of the unfolding action. Each figure in the painting has a clear and distinct role, which plays out fully in accordance with perceived or expected behaviors of Old South mores and customs regarding the selling of slaves. Consequently, there is nothing truly surprising about the painting—similar visual expressions had long appeared in related forms of public media such as book illustrations, etchings, drawings, and lithographs—except the revelation that the centralized female is a victim of the auction block.

The painting’s main focus is the bidding process during the sale of a “white slave.” Such women, particularly in the New Orleans region, were known as “fancy gals”; a term sometimes used loosely to refer to enslaved females of admirable beauty and light complexion whom white owners often forced into providing sexual favors.[29] Adrienne D. Davis explained of this aspect of their expected “duties”:

Slavery also extracted sexual labor from enslaved women. Enslaved women found themselves coerced, blackmailed, induced, seduced, ordered and, of course, violently forced to have sexual relations with men. Sexual access was enforced through a variety of structural mechanisms. Most overtly, the South established markets that sold enslaved women for the explicit purpose of sex. In so-called “fancy girl” markets, principally in southern port cities, enslaved women could be bought to serve as the sexual “concubines” of one man, or to be prostituted in the more contemporary understanding of the term. According to one historian, we might understand “fancy” as referring to markets “selling the right to rape a special category of women marked out as unusually desirable.”[30]

On purely economic terms, “fancies” were expensive to buy and profitable to sell. Some estimated their purchase price to be thirty percent more than the best female field slaves or, according to one source, they “occasionally reached three hundred percent of the median prices paid in a given year—prices above $1500 in the first decade of the century and ranging from $2000 to $5233 afterwards.”[31] Former slave Solomon Northup echoed, “There were men enough in New Orleans who would give five thousand dollars for such an extra fancy piece . . . rather than not get her.”[32]

Compositionally, The Slave Auction is set in front of a countryside hotel somewhere along a river in the Deep South, likely New Orleans, where the artist portrays the selling of a beautiful young light-complexioned slave dressed in an elegant gown. At first glance, the woman could easily be mistaken for a white, but on closer inspection, it is clear that she is the object of a slave auction. As the auctioneer extols her virtues and the slave trader mentally tallies his profit margins, the young woman submits by force to the unwanted physical contact of a potential buyer while half a dozen more white men stare intensely and lustfully. As a result, the young woman turns her head to the side, forlorn over the humiliating incident. At the bottom of the composition and placed at a direct diagonal from her, a young black man in a position of supplication gazes intently at the “prize” of the auction. This arrangement suggests that the two share some type of relationship and that he is now helpless to offer protection—a truly emasculated black man. Presented in this manner, the auctioned slave is clearly the white man’s ultimate sexual fantasy, who, as property, must fulfill her owner’s every wish, and whose final purchase price is appraised based on her potential for long-term service as a bed wench. The hotel setting suggests that after the transaction becomes final, the first stop in this new liaison will be a room inside.

A bevy of auction-related activity surrounds the young auctioned woman. Secondary to her plight is a dark-complexioned slave woman to her left who places her infant child on the ground in order to cling desperately to an older child whom a slave trader attempts to remove forcibly. Behind her, another white collaborator raises a whip to strike the blow that will forever separate mother and child. And behind them, more slaves huddle on the ground contemplating their immediate fate and their unknown future.

The use of the very light-skinned woman as the focal point of this painting is, again, consistent with abolitionist writings and popular plays. Her depiction as a victim of “white slavery” and of a society steeped in aggressive objectification of defenseless black bodies allowed white northern viewers, the intended audience, to more readily identify with the appalling dehumanization of the auction experience (the narratives, novels, and plays had already successfully established this pattern of behavior). In this process of visual confirmation of slave practices in the South, the artist introduces an additional layer of abolitionist reasoning, and moves the painting’s narrative beyond the obvious physical black/white confrontations depicted, and reaches a level wherein a subtle underlying commentary casts the white male participants in a different light—other than merely evil, stereotyped, savage predators. This negotiation of the painting requires a little more work from the less-informed viewer, but it is, nevertheless, an important and perhaps necessary part of fully decoding The Slave Market and other similar art works. Viewed from the perspective of the white males, the dynamics of the business end of slave auctions unfolds sharply—some men are paid to separate, restrain and punish; one receives compensation for auctioning off black bodies; one sits back and counts his profits as the bids rise; and more importantly, the majority of those depicted—the “lords of southern aristocracy” and the ones with real power—stand by and calculate the monetary value of the auctioned slave for profit, pleasure, or both.

Therefore, it is possible that the painting also offers direct commentary on the considerable financial sway that the wealthy slave-owning class exerted on the South. In other words, those capable of purchasing these women wielded as much influence, dominance, and authority in southern society and the shaping of its destiny as they did with a “fancy” on an intimate level. Walter Johnson suggests how “fancy gals” played an important role in this dynamic of private and public clout.

For, though “fancy” women were sold through private bargaining as well as public crying, the open competition of an auction—a contest between white men played out on the body of an enslaved woman—was the essence of the transaction. . . . The high prices were a measure not only of desire but of dominance. No other man could afford to pay so much; no other man’s needs could be so substantially measured; no other man’s desires would be so spectacularly fulfilled.[33]

Paintings like The Slave Auction that feature “white slaves” inevitably bring into question the complexities of their existence and their place in American society. In the real world, painted on canvas, or carved in stone, “white slaves” surely pondered, in these incarnations, a satisfactory accounting of their racial status in American society and their role as a caste caught between those deemed as “superior” and those designated as “inferior.” Of course, a definitive answer to the specificity of the racial identity of an individual remains as elusive in the present as it did during the antebellum period. Indeed, every portrayal rendered of “white slaves” reflected the strong subtext of a nation grappling with defining and confirming the boundaries of racial lines.

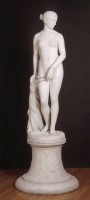

The Slave Market echoes an earlier work of art embraced by the abolitionists as symbolic of their mission, Hiram Powers’s marble statue, The Greek Slave (fig. 5). The sculpture presents a helpless white woman forced into a state of bondage and nudity in which the preservation of their virtue appears fleeting. Powers’s work, rendered in the popular neoclassical style, depicted a captured Christian girl placed for sale in a slave market in Constantinople by the Turks.[34] When the work came to America for extensive exhibition in New York, New England, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Louisville, St. Louis, and New Orleans, contemporary accounts and recorded public reaction indicate that any connection of the sculpture to American slavery was lost on the majority of its audience.[35] Still, the power of the statue, from its skillful rendering to its compelling background narrative, earned it the reputation of being arguably the most famous sculpture of the nineteenth century. However, only abolitionists and their supporters seized upon the work as embodying a not-so-veiled linkage to African Americans in bondage.[36] According to Alexander Nemerov, the Vincent Scully Professor of the History of Art at Yale University, Powers’s motivation to create the work actually sprang from deeper, race-based American roots. He stated, “Powers was angered by the notion of slavery and this anger became his inspiration for The Greek Slave. The sculpture became an allegory for abolition and slavery in America.”[37]

Similarly, one contemporary critic for the Eastport Sentinel seized upon the connection between The Greek Slave and the continued practice of dealing in human chattel in the United States, saying:

There is a painful significance . . . in the fact, that this masterpiece of our gifted American Artist should represent a youthful female slave. In no country could the truth and reality of the picture be better felt and understood. It brings home to us the foulest feature of our National Sin; and forces upon us the humiliating consciousness that the slave market at Constantinople is not the only place where beings whose purity is still undefiled, are basely bought and sold for the vilest purposes, — and the still more humiliating fact that while the accursed system from which it springs has well nigh ceased in Mahomedan countries, it still taints a portion of our Christian soil, and is at this very moment clamoring that it may pollute yet more.[38]

Thus, the abolitionists’ decoding of The Greek Slave proved correct, and the statue, for them, became a visual metaphor for black bondage in America, especially slaves vulnerable to sexual predators in the guise of slave owners and traders.[39] Despite the lack of any overtly physical racial qualifiers found on The Greek Slave, Charmaine A. Nelson suggests that “the symbolic trigger in The Greek Slave that located the possibility of an abolitionist interpretation was the chains.”[40] Apparently, the restraints alone were enough to provide visible resonance among those lobbying against slavery. At the very least, they could capitalize on the statue’s popularity and wide viewership to provide a new and readily identifiable platform from which to further their agenda.

Nelson also asserts that Powers—by rendering his slave as white and Greek “in the midst of the political turmoil of American slavery”—missed the chance to make a profound statement against American chattel slavery.[41] She also comments on Powers’s need to keep the defining limits of black beauty under wraps at that time, saying, “If one looks at the landscape of black female subjects in neoclassical sculpture of the era, we see not the absence of black female subjects as slaves, but their absence as beautiful subjects rendered in compositions which produced narratives that called for the dominantly white audience to view them as equals and/or as sympathetic victims of slavery.”[42] Again, the main female character in The Slave Market not only subverts the genre through her subtly understood “blackness,” but also challenges its viewers to measure their tolerance of “acceptable” black beauty.

The Greek Slave, as viewed by those attuned to its connection to American slavery, translated and equated the white marble body of the sculpted woman to the white flesh of an octoroon “captive,” metaphorically and morally. The woman in Powers’s work, like the octoroon in The Slave Market, is in desperate need of rescuing from forces that defile the sanctity of womanhood in the Victorian era. In this case, she is young, innocent, white, and Christian—a potent combination for sympathy and liberation.

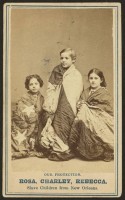

Similarly, commenting on widely circulated cartes de viste of three near-white slaves (fig. 6) discovered and freed in New Orleans in 1863, historian Mary Niall Mitchell tied the plight of the fictional woman embodied in the The Greek Slave to the immediate reality of the abolitionist’s crusade in redeeming “white slaves.” She stated:

Although the visual clues given in the photographs of Mary, Rosa, and Rebecca are quite different from those belonging to The Greek Slave and [Erastus Dow Palmer’s] The White Captive [1858], a narrative of lust was common to all of them. If the sculpted women were poised at the threshold of a horrifying scene, the white-looking slave girls stood on the slim ground of girlhood—their youth, their skin, and the knowledge that they had been enslaved combining to suggest a harrowing future. Also, by their perceived powerlessness, both sculptures and the white-looking girls seemed to hold the viewers sway. Yet though audiences had no control over the fate of The Greek Slave or The White Captive, abolitionists made the point that for little slave girls (and young mixed-race women) in the South, it was not too late. Where the sculptures could only inspire agony, the images, as propaganda, could inspire action. The endangered virtue of white and white-looking little girls, in turn, made appeals for their protection all the more urgent and made the thought of not helping them a scandalous one.[43]

Thus, the abolitionists, again, incorporated racially sensitive visual fodder in photographs of “white slaves” to command the public’s attention and strategically harvest the seeds of righteous indignation over their secure place in American society.

The Redeeming of Pink

In The Slave Market, the abolitionists profoundly delivered their message in visual terms that brought the issue of “white slavery” disturbingly close to all who viewed it in the North. The strategy of art utilized as an abolitionist “weapon” also appears in Eastman Johnson’s, The Freedom Ring, which depicts a “white slave” child contemplating her recent emancipation.[44] Unlike The Slave Market, this work, based on an actual person and event, carries a historiography that places it firmly within the antislavery movement’s public illumination of the lives of near-white slaves.

The origin of The Freedom Ring is well documented and emerged from the leadership provided to the members of the Plymouth Congregational Church of Brooklyn, New York, by its pastor, Henry Ward Beecher (1813–87).[45] From the time he preached his first sermon at the church in 1847, Beecher, the brother of abolitionist author, Harriet Beecher Stowe, announced that his teachings from Christ’s Gospel would not ignore contemporary issues including slavery.[46] Beecher, true to his word, led the congregation at Plymouth Church on a path of love, healing, and freedom that often confronted the bigotry of race relations and bondage in America directly.

Beecher’s most effective and visible method of addressing slavery was to hold mock auctions in his church. This arose from his participation, in 1848, in a rally sparked by the capture of the Pearl, a schooner involved in the smuggling of 77 slaves from Washington, DC to the North. Most of those fugitives quickly returned to bondage and some, including two light-complexioned teenage girls, Mary and Emily Edmondson, found themselves sold to the Deep South. Following their transport to New Orleans, their owner subsequently moved to Alexandria, Virginia, to escape an epidemic. The girls’ father, Paul, desperately sought their release and eventually requested that Beecher intervene. The price of the sisters’ freedom was $2,200 and Beecher, from the pulpit of Broadway Tabernacle in New York City, imitated “the call of a slave trader’s auction, [and] encouraged people in attendance to contribute the large sum of $2,200 to secure their freedom.”[47] So moving was Beecher in his plea for justice that a witness to the proceedings proclaimed that the abolitionist pastor “would have made a capital auctioneer if he had chosen that business.”[48] The Edmonson sisters gained their freedom through this process, and Beecher continued to use mock auctions as part of his theology of liberation.

One of his earliest attempts at slave redemption within the walls of Plymouth church involved the auctioning in 1856 of Sarah, described as a young mulatto about twenty-two or twenty-three (fig. 7). Sarah was the daughter of a Virginia slave owner and one of his slaves. Her father wished her sold further south. The slave trader entrusted to sell her was so moved by her beauty and the prospect of her dreadful future as a concubine that he contributed $100 toward the purchase of her freedom and allowed her travel to New York to help raise her $1,200 purchase price.[49] The New York Daily Times recounted her introduction to Beecher’s congregation of three thousand: “The slave rose in her seat, a tall fine looking woman, with barely enough tinge in her complexion and wave in her hair to betray her colored blood, and hardly an eye in the immense audience but as wet with sympathetic tears, as she, trembling, and completely with emotion, stumbled up the pulpit stairs.”[50] Beecher then questioned his parishioners, “What will you do now? May she read her liberty in your eyes? Shall she go out free? Christ stretched forth his hand and the sick were restored to health; will you stretch forth your hands and give her that without which life is of little worth? Let the plates be passed and we shall see.”[51] As before, Beecher acquired the purchase price and Sarah gained her freedom.[52]

Beecher’s use of mixed-race slave children and young women served as a “lightning rod” for redemption. He assumed correctly that his congregation would be more receptive to contributing money for their emancipation when the “auctioned” slave’s skin color approximated their own. His appeal also carried the implicit subtext that female “white slaves” were not destined for the fields, but for sinful sexual encounters with men who counted them as property. Thus, Beecher’s mock auctions can also be viewed as mock trials designed to indict and convict the practice of “white slavery” by publically exposing the “dirty, private secrets” of immoral southerners.

Furthermore, these mock auctions, when viewed on the level of theatrical performances (which they inevitably were), offer a different perspective on the role Beecher played as auctioneer/redeemer/actor before his captive audiences. Although Beecher claimed the moral and religious high ground as a basis for rescuing young female slaves, he was, nonetheless, complicit in extending the trade to the North—bodies exchanged for money even for a more favorable outcome still profits slave owners—thus making his church an actual auction house where the thrill of the sale, for the congregation, enveloped Plymouth as much as any slave-trading center in the South. According to Jason Stupp:

Looking back at Beecher’s auctions, however, reveals a contradiction: while claiming to celebrate freedom, the performances simultaneously reinforced white superiority and situated white spectators as moral redeemers who could participate in the horrors of slavery without endangering their religious beliefs. Indeed, although they worked under the abolitionist banner, Beecher and his congregation were still actors complicit in the system of buying and selling slaves. Could Plymouth Church, then, be understood as a distinct form of slave marketplace?[53]

Beecher brought another slave into Plymouth Church in February 1860, for the purpose of emancipation. She, like those who preceded her, took center stage and Beecher elucidated her dire predicament. Her name was Sally Maria Diggs (c. 1851–?), but nicknamed Pink for her white complexion, and described as “too fair and beautiful a child for her own good.”[54] Pink’s future was easily foretold—a life in the South where her innocence was only temporary and where, within a few years, she would be vulnerable to unbridled sexual advances, much like the fate realized by the octoroon in The Slave Market.

Pink’s journey to Beecher’s church was typical for Beecher’s brand of slave purchasing. She was born into slavery in 1851 in Port Tobacco, Charles County, Maryland. Their owner sold her mother and two brothers to the state of Virginia when she was seven years old and she and her grandmother were sold to a slave owner in Baltimore. The grandmother eventually secured the funds to purchase her own freedom, but could not do so for Pink. The grandmother contacted Beecher, and Pink was “negotiated” to the North backed by the preacher’s solemn promise to return her if the agreed-upon price was unattainable.[55]

According to one account, the congregation “saw Pastor Henry Ward Beecher mount the pulpit, accompanied by a trembling nine-year-old Negress. Then, while many a woman became hysterical, while many a man shed tears, famed Abolitionist Beecher turned his pulpit into a slave-pen, his sermon into an auctioneer’s harangue, asked his hearers to bid $900 for this fine piece of colored flesh.”[56] The attending members had the power to free the child from a tragic life as a slave and the collection plate circulated among them. Amid the emotionally charged offering of which Beecher said, “And rain never fell faster than the tears from many of you here,” a woman in the congregation, author Rose Terry Cooke dropped an exquisite opal ring into the collection plate.[57] When Beecher realized they raised enough money, more than $2000, to secure Pink’s liberty, he took the ring from the plate, placed it on the girl’s finger, and said, “With this ring I do wed thee to freedom.”[58] Shortly after attaining her emancipation, Pink resided with a family in Brooklyn and changed her name to Rose Ward, in honor of her benefactors (fig. 8).[59]

Beecher commissioned Eastman Johnson to paint the child and the ring that helped free her. Johnson was a New Englander who received extensive art training abroad. He studied in the major European art centers of Dusseldorf, The Hague, and Paris from 1849 to 1855. Upon his return to America, he became aware of the intensifying debate over slavery and the effect it was having on the country’s political, social, and economic climate. Johnson’s first encounter with slaves as subjects in his compositions came in 1857, when he traveled to Mount Vernon to render scenes of the famous home of George Washington. Included in the resulting paintings were slaves who still resided on the plantation.[60]

However, it was his next depiction of African Americans as slaves that garnered him a national reputation and great public acclaim. This painting, Negro Life at the South (fig. 9), was not set on an agricultural estate in the Deep South, but, instead, in Washington, DC, close to the residence of his father.[61] In fact, the setting was readily identified as urban in early reviews, but it slipped into the realm of “happy darkies down South” when it became more commonly known as Old Kentucky Home after the popular Stephen Foster song.[62]

Negro Life at the South was a large composition that demonstrated Johnson’s mastery of manipulating and balancing multiple, clearly delineated figures (thirteen in all) within a restrictive pictorial space. The scene displays city-dwelling slaves caught at a time of leisure, situated in an open area next to their owner’s home. Behind them is an old dilapidated building, presumably their home. Johnson presents his figures in groupings; an old banjo player anchors the center of the painting surrounded by a thoroughly entertained mother and several amused children. To the right, a white woman, accompanied by her attending slave, gazes inquisitively into the world of chattel property. To the left, a young couple engages in the act of courting, the woman portrayed as a fair-skinned mulatto, quadroon, or octoroon much like those redeemed at Beecher’s church. And above them, in a second-story widow, a “mammy-type” and a baby bask in the tranquility of slave life in Washington.[63]

Negro Life at the South’s rise to prominence came after Johnson exhibited it at the National Academy of Design in April 1859. Hailed as an unqualified masterpiece, viewers and critics still had different opinions of the painting’s meaning. Some interpreted it as the quintessential visual testament that assured slave life was one of perpetual contentment and fulfillment. Others saw it as an indictment of the institution, the crumbling building in the background as an allegory for the unsteady foundation on which the nation teetered over the slavery issue Still others were perplexed over its intended messages, but, nevertheless, likely admired it for its attempt at portraying African Americans in a realistic manner. According to the New York Evening Post, “Above all, Negro Life at the South was commended for the characteristic types it catalogued visually, for its seeming “truthfulness of expression,” “reality of character,” and “honesty of painting.”[64] Johnson appears to have kept his political beliefs private at the time he unveiled Negro Life at the South and his views of African Americans, at least on his canvases, ambiguous. Yet, for a painting that gained Johnson such instant celebrity, his true intentions remained a close secret that left his audience contemplating contradictory binaries of the period—slavery or freedom, justice or inequality, and tolerance or bigotry.

It is likely that Beecher saw Negro Life at the South in New York and judged Johnson’s sympathies as lying with the abolitionists. Johnson’s family was decidedly pro-Union, and while a student in The Hague, he produced a painting based on the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In addition, the Pearl incident took place in Johnson’s former hometown, Washington, DC. But Beecher’s choice of Johnson to bring Pink’s predicament to canvas and a wider audience suggests that he knew something about the artist that made him the perfect candidate. Consequently, it is possible that Johnson, by living in New York, was influenced by Beecher’s sermons and may have even attended his church. Johnson’s depiction of Pink in The Freedom Ring shows her sitting alone on the floor of a dimly lit room, her attention fixed on the symbolic ring that she wears on her right index finger.[65] Her face reflects not a trace of African ancestry, in keeping with Beecher’s appeal. An open trunk, perhaps the one that contained her meager possessions on her journey to New York, and a shawl-strewn stool frame her small body. Johnson’s portrayal of Pink may seem an overly sentimental and romanticized handling of the issue of “white slavery,” but the fact that the painting originates from a real-life incident with a satisfying ending justifies his idealistic treatment. For those who knew her story, Pink appears safe from the true auction block, the lash of the whip, and the abuse of a cruel master. Johnson, through his sensitive interpretation, rewards Pink with a moment of solitude and reflection over her newfound freedom, the extreme opposite of the ordeal suffered by the octoroon in The Slave Market.

Beecher did not own The Freedom Ring, but he knew its worth as a valuable piece of abolitionist propaganda. Prints were made of the painting (Beecher had one hanging in his parlor) to enhance Pink’s tale as it circulated widely in the North.[66] Johnson showed the painting in the National Academy’s 1860 spring exhibition along with two other slave scenes, Kitchen at Mount Vernon (1857) and Mating (1860), and he continued to explore African American themes throughout the Civil War and into Reconstruction. His interest in “white slavery” resurfaced during the time he spent with Union troops as a sketch artist at the battle of Bull Run near Manassas, Virginia. There, he witnessed a slave family fleeing their captivity on horseback. He later transferred that memory into a painting, A Ride to Liberty—The Fugitive Slaves (ca. 1862), which contained a near-white mother seated behind her husband and child, a clear indicator that he was still intrigued with the plight of “white slaves.”

An American Dilemma Above and Below the Mason-Dixon Line

Although the creators of The Slave Market and The Freedom Ring clearly staged and manipulated representations of “white slaves,” they both portrayed innocent victims of an insidious, sexually depraved side of slavery. As news of near-white girls being sold on the auction block filtered to the North, many of its citizens reacted with shock, yet they clamored for more information of the practice in the form of newspaper accounts, novels, short stories, slave narratives, and theatrical productions.[67] And, as has been discussed, some abolitionists found opportunity to advance their mission by placing the issue of “white slavery” at the forefront in visual terms. The result for some, particularly in the North, was an increased demand for immediate action to save very light-complexioned slaves from peril.[68]

The paintings of the Fancy Gal and Pink also represent a unique and uncomfortable allure developed by the northern public, in and out of abolitionist circles, over the plight of mixed-race slaves. While abolitionists used these works to advance their cause through empathy and moral outrage, the images also carried a degree of voyeuristic curiosity and “too close to home” racial confrontation. Painted depictions of slaves in the antebellum period, particularly related to their sale, uniformly showed mixed race or near-white young women for a specific reason. The messages contained in these works, fully realized or implied, condemn the practice of dealing in human chattel and expose its consequences on several levels. If northern creators and consumers of this art linked emancipation with a demand for egalitarianism, the need to supplant a dark body with a white body, pictorially, was unnecessary. But this was not the case, as near-white slaves, whether in literary form or on canvas, forced many northern whites to reflect on their own tolerance of racism and their views of racial identity boundaries.

The visual narratives contained in both paintings share a deeply infused balance of sanctified redemption and cultural racism. If the Fancy Gal and Pink represented a mirror to the soul of whites, that reflection foretold a future where racial purity was uncertain and, ultimately, jeopardized the perpetuation of white privilege and white supremacy. The fascination with “white slaves” for many northerners, including the abolitionists and their supporters, centered on the same one drop of “black blood” that justified slave traders in selling them. For those advocates of emancipation, however, that one drop was all that was required for “white slaves” to be marginalized, objectified, and unqualified to join the white race on equal terms.

In addition, portrayals of mulattoes, quadroons, and octoroons supported, for many in the North, the notion that they maintained a moral and religious advantage in the debate over slavery and the perpetuation of the institution. Northerners and southerners had long argued the acceptance or rejection of slavery based on biblical interpretation. Proslavery advocates found blessed reassurance of God’s approval of human bondage in the chapters of the Old Testament (the curse of Ham was a favorite) and antislavery advocates rallied around the linkage of the institution with unequivocal sin that led to damnation.[69] The mere existence of “white slaves” and the commodifying of their images, therefore, gave abolitionists a visible means to connect the sexual transgressions of white men in the South to moral degradation. According to Jules Zanger:

The octoroon, to the North, represented not merely the product of incidental sin of the individual sinner, but rather what might be called the result of cumulative institutional sin, since the octoroon was the product of four generations of illicit, enforced miscegenation made possible by the system of slavery. The very existence of the octoroon convicted the slaveholder of prostituting his slaves and selling his children for profit. Thus, the choice of the octoroon rather than the full-blooded black to dramatize the suffering of the slave not only emphasized the pathos of the slave’s condition but, more importantly, emphasized the repeated pattern of guilt of the Southern slaveholder. The whiter the slave, the more undeniably was the slaveholder guilty of violating the terms of the stewardship which apologists postulated in justifying slavery.[70]

Thus, the Fancy Gal and Pink are both symbolic of the innocent and the illicit. In this regard, perhaps sorting out blood fractions for the sake delineating social limitations was the definitive manifestation of the “white man’s burden,” in the North and in the South.

Paintings like those presented in this article are pure abolitionist artistic propaganda rendered to engage the viewer at a visceral level and appeal to Victorian standards of purity, justice, and decency. Audiences standing before these works with any knowledge of the predicament of “white slaves” certainly felt an emotional connection to their plight. These paintings, and others like them, struck a responsive chord in viewers that likely cared little about the mistreatment of dark-skinned slaves far removed to the cotton fields of the South. If the sale of “white slaves” served as an increasing source of public embarrassment below the Mason-Dixon Line, then their artistically rendered equivalents in the North served as a powerful catalyst for change that required northerners to view slavery in a different light. As has been shown, artists like the unknown painter of The Slave Market and Eastman Johnson transformed themselves into effective contemporary spokespersons about “white slavery” and gave the abolitionists and their supporters another means to move toward the eradication of the institution.

I thank Dr. George Dimock for his guidance, support, and friendship.

[1] Sarah Burns, “Images of Slavery: George Fuller’s Depictions of the Antebellum South,” The American Art Journal 15, no. 3 (1983): 36.

[2] Ibid.

[3] I use the terms “white slaves” and “white slavery” from their common usage during the antebellum period. They reference any slave of mixed racial heritage whose complexion and physiognomy was close to or indistinguishable from Caucasians. The words mulatto, quadroon, and octoroon, although originally designated to represent racial admixtures of one-half, one-fourth, and one-eighth black ancestry, eventually became interchangeable as descriptors of racial pedigree. In theory, one pure white parent and one pure black parent produced a mulatto; one pure white parent and mulatto parent produced a quadroon; and one pure white parent and one quadroon parent produced an octoroon. Degrees of blackness and limits of whiteness have long been a point of contention in the United States with the “one-drop rule” becoming the de facto qualifier for many. Even Thomas Jefferson wrestled with this quandary and declared that after three racial crossings (an octoroon) the person was white and entitled to citizenship. Of course, if he fathered children with his slave, Sally Hemings, he would have classified them as octoroons and, therefore, considered white and free. The demand for “white slaves” negated serious consideration and adoption of this social structuring, and anyone light enough with the potential for profit, no matter how little “black blood” they contained, could find themselves on the auction block. See F. James Davis, Who is Black?: One Nation’s Definition (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991).

[4] African Americans have appeared in American art from as early as 1710. By the nineteenth century, their presence graced the oeuvre of many noted and lesser-known American artists, usually as subjects in genre scenes. Although blacks were used mostly within compositions to give them a unique American distinction, many genre paintings of this period, including Eastman Johnson’s, portrayed African Americans in a positive manner that advanced their humanity. See Guy C. McElroy, Facing History: The Black Image in American Art 1710–1940 (San Francisco: Bedford Arts, 1990); and Albert Boime, The Art of Exclusion: Representing Blacks in the Nineteenth Century (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990).

[5] Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997), 23.

[6] Hugh Honor, in his study of the black image in western art, states that, “there seems to have been as little demand from abolitionists for depictions of the horrors of slavery as from opponents of blood sports for hunting scenes.” Hugh Honor, From the American Revolution to World War I, The Image of the Black in Western Art 4 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989), 202–3. He implies that visual images of slavery were most likely found as engravings and prints as illustrations in slave novels and narratives beginning with Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852. Still, there are several extant paintings and sculptures created during this period that contain strong anti-slavery messages, including early works such as Liberty Displaying the Arts and Sciences (1792) by Samuel Jennings and Portrait of Cinque by Nathan Jocelyn (1839), even though there was no unified effort among large abolitionist groups to promote them. It must be assumed, however, that these works were created by artists who shared an abolitionist objective or were commissioned by those who did. In addition, a multitude of prints and photographs of slaves were circulated in and out of abolitionist circles, those being more easily disseminated to the public. To be counted as an abolitionist, one did not have to belong to a recognized and organized group. Rather, the choice to become an abolitionist began as an individual decision to oppose the enslavement of human beings and then to connect with others sharing that ideal.

[7] The 1860 Census Had Three Race Categories: White, Black, and Mulatto. See “Multiracial in America,” Chapter 1: Race and Multiracial Americans in the U.S. Census, Pew Research Center, June 11, 2015, accessed July 20, 2016, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/06/11/chapter-1-race-and-multiracial-americans-in-the-u-s-census/.

[8] Joel Williamson, New People: Miscegenation and Mulattoes in the United States (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995), 68–70.

[9] Lawrence R. Tenzer, The Forgotten Cause of the Civil War: A New Look at the Slavery Issue (Manahawkin, NJ: Scholar’s Publishing House, 1997), 34–35. Also see Russel B. Nye, Fettered, Freedom: Civil Liberties and the Slavery Controversy (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1972), 308–9. Nye stated, “If a person who is 99.99 percent white could, through the status of the mother, be made a slave upon claim of the mother’s owner, the next step was an easy one to take. The fugitive slave laws and the Prigg [1842] and Dred Scott [1857] rulings [in the Supreme Court] tended to strengthen the argument. If there was no distinction between white and black slavery, and if a slaveholder possessed the right to pursue a slave into any state, he might kidnap and claim ownership of a white person.”

[10] Calvin Fairbank, During Slavery Times: How He Fought The Good Fight To Prepare The Way (Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2010), 26.

[11] Philo Tower, Slavery Unmasked, Being a Truthful Narrative of a Three Years’ Residence and Journeying in Eleven Southern States (Rochester: E. Darrow Brother, 1856), 307.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Frederika Bremer, The Homes of the New World: Impressions of America (London: Arthur Hall, Virtue & Co, 1853), 1:382.

[15] Frederick Marryat, Diary in America with Remarks on Its Institutions (New York: D. Appleton, 1839), 191.

[16] William Wells Brown, Narrative of the Life of William W. Brown, An American Slave (London: Charles Gilpin, 1849), 33.

[17] Tenzer, Forgotten Cause, 27.

[18] For a detailed account of this practice, see ibid.

[19] Early abolitionist interest in the plight of “white slaves” is found in the first work of United States antislavery fiction. See Richard Hildreth, Archy Moore: The White Slave or Memoirs of a Fugitive Slave, with a New Introduction Prepared for This Edition by Richard Hildreth (New York: Miller, Orten, and Mulligan, 1856). This book, first published in 1836, centers on the protagonist, Archy, the completely white-looking son of a slave-holding father and his slave mistress. The heroine, Archy’s lover, Cassy, is also the offspring of Archy’s owner/father and another slave. Hildreth’s detailing of Cassy as a victim of repeated attempts of sexual abuse from whites sets the tone for future tragic mulatto depictions in American literature and art.

[20] William Jay, Miscellaneous Writings on Slavery (Boston: John P. Jewelt and Company, 1853), 26.

[21] Slave narratives appeared in American literature from the 1830s to the 1860s, usually as a propaganda tool of the abolitionists advocating the end of slavery by exposing the insidious side of the institution through the lens of those formerly enslaved. Their first-hand testimonies, either personally written or dictated, not only provided readers with insightful accounts of the conditions that led to intense suffering and indignities they endured at the hands slave owners and their supporters, but also projected and reinforced the humanity of people of African descent largely based on well-understood religious and moral principles. Finally, slave narratives also allowed those living outside the South to gain additional knowledge of the customs and traditions of a region that would eventually go to war to preserve its way of life. As is shown, the paintings discussed in this essay share the same function in visual terms.

[22] See Sterling Lecater Bland, Jr. ed., Understanding 19th-Century Slave Narratives (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2016), 10.

[23] See Mary Niall Mitchell, Raising Freedom’s Child: Black Children and Visions of the Future after Slavery (New York: New York University Press, 2008).

[24] The Massachusetts Historical Society has identified the subject of this daguerreotype as “probably Mary Botts.”

[25] Quoted in Mitchell, Raising Freedom’s Child, 73–74.

[26] Boime, Art of Exclusion, 83–84. The terms mulatto, quadroon, and octoroon are often used interchangeably in nineteenth-century vernacular. In this case, Boime is describing a “beautiful octoroon,” but he is actually defining the racial admixture of a quadroon.

[27] Burns, Images of Slavery, 55–56.

[28] This painting is in the collection of the Carnegie Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. W. Fitch Ingersoll.

[29] These light-complexioned females were also referred to as “fancy girls,” “fancy women,” or simply as “fancies.”

[30] Adrienne D. Davis, “Slavery and the Roots of Sexual Harassment,” in Directions in Sexual Harassment Law, ed. Catharine A. MacKinnon and Reva B. Siegel (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 459.

[31] Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman, “New Orleans Slave Sale Sample, 1804–1862,” August 4, 2008, University of Rochester, ICPSR07423-v2 (Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research), doi:10.3886/ICPSR07423.v2.

[32] See Sue Eakin and Joseph Logsdon, eds., Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slave (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1968), 58.

[33] Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 113.

[34] Letter from Hiram Powers to Edwin W. Stoughton, November 29, 1869, cited in Linda Hyman, “The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers: High Art as Popular Culture,” Art Journal, 35, no. 3 (Spring 1976): 216.

[35] Charmaine A. Nelson, The Color of Stone: Sculpting the Black Female Subject in Nineteenth-Century America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 78.

[36] Editorial (unsigned), “Powers’s Statue of the Greek Slave,” Washington, DC National Era, September 2, 1847, accessed August 3, 2016, http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/sentimnt/snar01at.html; and Letter from S.F. to Frederick Douglass (editor), “The Greek Slave,” Rochester North Star, October 3, 1850, accessed August 3, 2016, http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/sentimnt/snar03at.html.

[37] Jordan Konell, “Nemerov Talks American Art, ‘The Greek Slave,’” Yale Daily News, September 21, 2011, accessed October 12, 2014, http://yaledailynews.com/blog/2011/09/21/nemerov-talks-american-art-the-greek-slave.

[38] Clipping from the Eastport Sentinel dated August 23, 1848, quoted in Vivian M. Green, “Hiram Powers’s Greek Slave: Emblem of Freedom,” American Art Journal 14, no. 4 (Autumn 1982): 38n40.

[39] For a thorough account of The Greek Slave and its linkages to the abolitionist ideal, see Nelson, Color of Stone; and Beth Fadely, “A White Slave in America: Hiram Powers’s Greek Slave and the Cultural Construction of Race” (master’s thesis, University of South Carolina, 2010), accessed August 20, 2014, http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/171 [login required].

[40] Nelson, Color of Stone, 86.

[41] Menachem Wecker, “The Scandalous Story Behind the Provocative 19th-Century Sculpture ‘Greek Slave,’” Smithsonian.com, July 24, 2015, accessed, August 9, 2015, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/scandalous-story-behind-provocative-sculpture-greek-slave-19th-century-audiences-180956029/?no-ist.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Mitchell, Raising Freedom’s Child, 77–78. The “Mary” referenced here is Mary Botts. In the January 30, 1864, issue of Harper’s Weekly, northerners were introduced to a large engraving that featured Charles Taylor, Rebecca Huger, and Rosa Downs, three newly emancipated slave children who appeared to have no discernible “black features.” Public interest grew substantially when a public tour of the group in New York and Philadelphia was accompanied by the printing of dozens of individual and small-group portraits on cartes de visite. While many viewed the members of the group as mere curiosities, abolitionists distributed their images for fund-raising and increasing awareness to their plight.

[44] This painting is located in the Hallmark Fine Art Collection, Hallmark Cards, Inc. Kansas City, Missouri.

[45] For a detailed account of the life and work of Henry Ward Beecher, see Debby Applegate, The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher (New York: Doubleday Religious Publishing Group, 2007).

[46] H. Henry Howard, “Henry Ward Beecher: Plymouth Church,” Sidney Morning Herald, October 29, 1927, accessed June 20, 2016, http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/28054523. Also see “Henry Ward Beecher,” Our History, Plymouth Church, updated June 28, 2014, accessed July 23, 2016, http://www.plymouthchurch.org/history/article388259.htm?links=1&body=1.

[47] Frank Decker, “Working as a Team: Henry Ward Beecher and the Plymouth Congregation in the Anti-Slavery Cause,” International Congregational Journal 8, no. 2 (Fall 2009): 36.

[48] William C. Beecher and Samuel Scoville, A Biography of Henry Ward Beecher (New York: Charles L. Webster and Co., 1888), 293.

[49] Wayne Shaw, “The Plymouth Pulpit: Henry Ward Beecher’s Slave Auction Block,” American Transcendental Quarterly 14, no. 4 (December 2000): 335.

[50] “An Affecting Incident at Mr. Beecher’s Church—a Slave Girl upon the Platform—$883 Contributed on the Spot for Her Redemption,” New York Daily Times, June 3, 1856, 3.

[51] Beecher and Scoville, Biography of Henry Ward Beecher, 298.

[52] Some money had previously been donated in Washington to purchase Sarah’s freedom prior to her coming to New York. In the aftermath of emancipating Sarah, her story becomes conflicted. Apparently, Beecher failed to reveal that Sarah was already the victim of a sexual predator, a physician from Baltimore, who impregnated her. It was only after she ran away to Baltimore to escape her own father’s advances that her owner agreed to sell her. Beecher also raised enough money to buy her child’s freedom. See, “An Affecting Incident at Mr. Beecher’s Church,” 3.

[53] Jason Strupp, “Slavery and the Theater of History: Ritual Performance on the Auction Block,” Theater Journal, 63, no. 1 (March 2011): 72.

[54] Shaw, “Plymouth Pulpit,” 340. Diggs was also referred to as “Little Pinky.”

[55] “Negroes Again: Pinky,” Time Magazine, May 23, 1927, 68.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Shaw, “Plymouth Pulpit,” 341.

[58] Quoted in Patricia Johnston, ed., Seeing High and Low: Representing Social Conflict in American Visual Culture (Berkley: University of California Press, 2006), 108.

[59] Pinky eventually returned to Washington and attended Howard University. She became a schoolteacher and later married a lawyer, James Hunt. Pinky retained a copy of her “bill of sale” into old age. See “Negroes Again: Pinky,” 68.

[60] For a detailed account of the life and work of Eastman Johnson, see Teresa Carbone and Patricia Hills, Eastman Johnson: Painting America (New York: Rizzoli, 1999).

[61] Johnson’s father, Phillip, did not own slaves, but his second wife, Mary Washington James Johnson, owned three. The number of slaves included in Negro Life at the South, therefore, precludes them from all belonging to the Johnsons and suggests that Eastman selected other blacks from the neighborhood to serve as his models. In addition, some art historians believe that one of Johnson’s his sisters is the white woman that looks into the slave compound. See, John Davis, “Eastman Johnson’s Negro Life at the South and Urban Slavery in Washington, D.C.,” Art Bulletin 80, no. 1 (March 1998): 70.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Quoted in Davis, “Eastman Johnson’s Negro Life at the South,” 70.

[65] Eastman Johnson painted this portrait after seeing Pinky sitting on the ground looking at her “freedom ring.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 21, 1934, 1, cited in “Pinky Looking at Her Freedom Ring,” Brooklyn in the Civil War, Brooklyn Public Library, accessed August 2, 2016, http://www.bklynlibrary.org/civilwar/cwdoc013.html.

[66] Beecher used other visual images to elicit sympathy and support for his cause. Three months after Pinky gained her freedom, another child, this time from Virginia, was brought before Beecher to be redeemed. Her name was Fanny Cassiopeia Lawrence. According to the story surrounding her, Fanny was found “sore, tattered, and unclean” by a nurse caring for Union soldiers in Fairfax, Virginia. The slave girl, indistinguishable from white, was taken to New York where public attention made her somewhat of a national celebrity. Beecher saw great value in promoting Fanny, like the others, as the “ultimate victim” of slavery and, therefore, the ultimate propaganda tool. Several carte de visite photographs were taken of her, reproduced, and enthusiastically collected in the North. Young Fanny was later taken on a tour of major northern cities and “displayed” before those familiar with and sympathetic to her story.

[67] Tenzer, Forgotten Cause, 33–37.

[68] See Mitchell, Raising Freedom’s Child, 73–90.

[69] See John R. McKivigan, The War Against Proslavery Religion: Abolitionism and Northern Churches, 1830–1865 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984).

[70] Jules Zanger. “The Tragic Octoroon in Pre-Civil War Fiction,” American Quarterly 18, no. 1 (March 1966): 66.