The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Readers familiar with Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women may well remember the character of Amy, the youngest of the March sisters who longed to be a professional artist, only to give up on that dream after marrying Laurie. What is less well known is that Amy’s character was based largely on Louisa’s youngest sister May, who similarly was an artist and longed to travel to Europe to pursue her professional goals. It is also true that both May and Amy were pampered by family members, worried about the shape of their noses, and liked fine things—and in respect to May, the latter trait is quite apparent in a portrait painted by her Parisian roommate, Rose Peckham (fig. 1).[1] However, that may be where the resemblances end. May was able to independently forge a successful career as an artist, and was more interested in empowering other women to do the same rather than fashioning herself into a graceful, domesticated butterfly.[2]

Like many other American artists of the period, May sought to improve her skills and gain greater critical acclaim through study with European artists, such as T. L. Rowbotham Jr. in London and Edouard Krug in Paris. Somewhat unusually for an American woman artist of the period, she made not just one but three distinct and purposeful study trips to Europe (primarily London and Paris) during the 1870s before settling in Meudon, France, following her marriage in 1878 to a Swiss businessman, Ernest (Ernst) Nieriker. May regularly wrote letters to her family about her artistic and social experiences abroad, excerpts from which have been published in the only biography on May Alcott Nieriker to date, written in 1928 by Caroline Ticknor.[3] Yet she also found time to write for a public audience, composing at least five newspaper or journal articles,[4] an unpublished 309-page travel narrative,[5] and her best-known work, an 87-page travel guide entitled Studying Art Abroad, and How To Do It Cheaply (1879). Art historians have turned to this latter work, one of the first guidebooks written for American artists, for its forthright commentary on artistic life in Paris, London, and Rome.[6]

Excerpts from Alcott Nieriker’s Studying Art Abroad, as well as her letters, can also be found in primary source anthologies such as Sarah Burns and John Davis’s American Art: A Documentary History,[7] and Wendy Slatkin’s Voices of Women Artists.[8] Yet, there has been little in-depth analysis of her written oeuvre.[9] In this article I will pursue a line of inquiry suggested by Slatkin, who noted that Studying Art Abroad is a “valuable document of the growing feminist awareness among women artists by the last decades of the nineteenth century.”[10] Through a focused examination of Alcott Nieriker’s published travel writings, I intend to show that she sought not only to raise awareness of discriminatory practices in the art world, but also to empower women of modest means (like herself) to venture abroad, in order to pursue their serious study of art.

May Alcott Nieriker’s Journey as an Artist

To better understand what motivated May Alcott Nieriker’s publications, we need to consider the prolonged and convoluted trajectory of her career as a professional artist, especially in light of the obstacles she faced as a middle-class American woman. Alcott Nieriker’s artistic journey and creations, to date, have received less attention than her writings;[11] what follows is an initial foray into this topic, upon which future research can build.

Given the Alcott family’s persistent financial difficulties during May’s formative years (her philosopher-father, Amos Bronson, owed several thousand dollars to creditors in 1840, the year May was born),[12] it is astonishing that the youngest daughter was able to pursue artistic training at all. But thanks to her indomitable passion for art, the support of liberally-minded parents, and financial assistance from her sister Louisa and other female relatives and family friends, May was able to cobble together relatively brief periods of artistic instruction from a variety of sources into a bona-fide art education. Her first formative experience was at the Boston School of Design, which May attended from at least December 1858 until April 1859.[13] The first art school in Boston, the Boston School of Design was founded in 1851 by Ednah Dow Cheney in order to give women an opportunity to gain skills as designers for manufacturing firms, a growing field of employment for women following the Civil War.[14] Yet May was interested in being a fine artist rather than a designer, and thanks to the teaching of Stephen Salisbury Tuckerman (1830–1904), she at least learned how to draw the human body, albeit from the study of casts of ancient sculpture.[15] May’s brief experience at the School of Design must have revealed to her that women artists needed more options in order to gain an education that was on a par with that of their male counterparts.

To make up for this institutional deficit, May received instruction in drawing, painting, and sculpture for brief periods throughout the 1860s from three of the foremost artists in Boston, namely David Claypoole Johnston (1799–1865), William Rimmer (1816–79), and William Morris Hunt (1824–79).[16] At the same time she taught drawing, first at Dr. Wilbur’s asylum in Syracuse, NY, then at Frank Sanborn’s school in Concord, and eventually at her own private studio in Boston.[17] According to Louisa, by 1868 May was offering five or six drawing classes in Boston, which provides some evidence of her success as a teacher.[18]

In 1868, May also provided four illustrations to part one of Louisa’s Little Women (see fig. 2 for one example), however, due to her lack of figure study, they were met with mixed reviews.[19] Clearly there was more for the young artist to learn, and having exhausted the limited educational opportunities for women artists in Boston, May’s next step, as was the case for many American artists in the nineteenth century, was to go to Europe. Not only did its museums present an abundance of artistic masterpieces for study and emulation, but Europe also offered highly qualified teachers and more esteemed exhibition opportunities. May had expressed a strong desire to go abroad as early as 1863;[20] yet, travel and study in Europe required a substantial investment of money. Serendipitously, like her alter ego Amy March, May (albeit at the more advanced age of 30), was invited to go to Europe as the travel companion of Alice Bartlett, a wealthy young family friend;[21] Louisa also was to come as their “duenna.”[22] Together the three women made the popular grand tour of Europe between April 1870 and May 1871.[23] This experience was critical for May as she gained confidence in venturing out on her own in foreign cities, a behavior that at least some of her American compatriots would have considered risky at best.[24] In a letter to her sister Anna, May wrote, “I am quite hardened now, and think nothing of poking round strange cities alone.”[25] Armed with a dagger “in case of emergencies,”[26] Alcott Nieriker was driven by her need to experience the world and its art, even if it meant riding on top of a carriage, despite the protestations of her travelling companions that she was “insane.”[27]

Trying to capture the beauty of the picturesque European sights quickly frustrated May, especially because she lacked experience in landscape painting. In a letter to her sister Anna she wrote, “If I could only use colors easily all would go well, but never having painted from nature, I am timid about beginning.”[28] Fortunately, at the conclusion of their European sojourn in May 1871, May stayed on in London to take watercolor lessons from T. L. Rowbotham, Jr.,[29] thanks to Louisa’s largesse.[30] Her studies were cut short, however, when in November 1871 she was needed back home in Concord due to the ill health of both her mother and Louisa.[31] Although May readily fulfilled her familial duties, she was not about to give up on her dream of being a fine artist. So in April 1873, again with Louisa’s financial support,[32] she returned to London to further develop her portfolio. Being in Europe, away from the constant demands of family life, was clearly liberating for May, who wrote, “So free, so busy, so happy am I that I envy no one, and find life infinitely rich and full.”[33] She soon came to realize both critical and financial success as an artist. Her copies of J. M. W. Turner’s paintings in the National Gallery not only sold well,[34] but also were critically hailed by John Ruskin, whose praise reverberated in the American press.[35] As Jacqueline Marie Musacchio has shown in her intriguing case study of Emma Conant Church, copy work could be instrumental in establishing an artist’s reputation, and was thought to be a suitable task for women artists given its reproductive nature.[36] Yet as critic James Jackson Jarves noted of Turner’s paintings, “It is as difficult to adequately understand as to copy him.”[37] Thus, May’s ability to successfully reproduce these paintings testifies to her skill as well as her penchant to seek challenges.

At the end of a year of study in London, May returned to Concord to take over family responsibilities from Louisa so that she could again concentrate on her writing. Despite these domestic duties, in 1875 May established the first art center in Concord, which was free to both men and women, inspired by her experience of the free opportunities to study art in Europe.[38] The Art Center was a significant accomplishment in her mother’s eyes: “I feel proud of my daughter’s capability in giving this town so decided an artistic impetus. Noble girl.”[39]

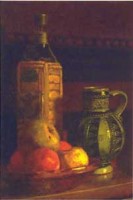

At thirty-five years of age, May had achieved success as a copyist of Turner, as a painter of decorative floral panels and watercolor vignettes of European sites,[40] and as an art teacher. Yet, she was not satisfied. In order to gain critical esteem, she needed to improve her skills in life drawing and in oil painting, which could not be readily achieved in America. Even Louisa admitted, “She cannot find the help she needs here.”[41] In September 1876, with further financial support from Louisa,[42] May left for Europe yet again, this time to study in Paris. She may have first attended the popular Académie Julian,[43] which was one of the few art schools in late nineteenth-century Paris that welcomed female students. Numerous American women, such as Elizabeth Gardner (1837–1922), Cecilia Beaux (1855–1942), and Anna Klumpke (1856–1942), attended the academy for a period of time, attracted by its promise of a rigorous course of study—one that prepared its male students to successfully apply to the esteemed École des Beaux-Arts.[44] However, May apparently grew dissatisfied with the higher fees incurred by the female students,[45] as well as the inferior studio conditions, and she soon left the academy. She found a more accommodating and reasonably-priced environment in the studio of painter Edouard Krug,[46] who also catered to female students, now coming to Paris in increasing numbers.[47] In Krug’s studio, May worked diligently to improve her oil painting technique, aided by criticism from visiting professor Charles-Louis (Carl) Müller (1815–92).[48] She soon achieved her first public success with the acceptance by the jury of the Paris Salon of 1877 of a small but accomplished still life (fig. 3).[49] As May proudly wrote to Louisa, the painting was one of 2,000 works accepted out of 9,000 submissions, and was further distinguished by being hung in a readily viewable position.[50] May commented on the potential implications of having her work hung at the Salon in an earlier letter to her mother: “If accepted it will be a very great honor, and a fine feather in my cap to start a career with, for color-dealers, picture-purchasers, and all nationalities, turn to the Salon catalogue as the criterion by which to judge of an artist whose name is unknown to them.”[51] The acceptance of Alcott Nieriker’s still life is furthermore notable because of her gender: only six other American women had artwork hung at the 1877 Salon, in comparison to thirty-eight American men.[52] Clearly, she was hitting her stride as a professional artist, even if at the relatively late age of 37.

May continued to live and paint in Paris until the fall of 1877, when she returned to London where, she believed, she had better opportunities for selling and exhibiting her works.[53] Indeed, she soon sold a painting through the esteemed Dudley Gallery, which was reported in the US press.[54] Her excitement was soon tempered, however, by the news of her mother’s death in November 1877. Despite her anguish at being far from her family, May remained in London, perhaps realizing that if she went back to the United States her serious pursuit of art would be over. While mourning her mother, May was comforted by a fellow boarder at her London rooming house, a young Swiss businessman named Ernest Nieriker, some fifteen years her junior but similarly interested in the arts.[55] The two fell in love and were married within a few months; by April 1878 the newlyweds were settled in the Paris suburb of Meudon.[56] Now a new challenge faced May, one that faced many professional women artists and writers, both actual and fictional,[57] who married: would she have to give up her artistic pursuits to tend to her household? In her letters home, May was adamant that she would not abandon her artistic career: “I mean to combine painting and family, and show that it is a possibility if let alone. . . . In America this cannot be done, but foreign life is so simple and free, we can live for our own comfort not for company.”[58] And with the support of her husband, she demonstrated that the dual role of wife and artist was possible; in fact, the years 1878–79 may have been Alcott Nieriker’s most prolific and successful period as a painter,[59] highlighted by the acceptance of a figure study titled La Negresse (fig. 4) at the Paris Salon.[60] Although her development had been slow, hampered by domestic interruptions and difficulty in finding adequate training, Alcott Nieriker had finally attained some measure of the success she had sought in the field of art. One can only wonder what more May might have achieved, had death not intervened in December 1879, just eight weeks after she gave birth to a daughter.[61]

May Alcott Nieriker as Writer and Advocate for American Women Artists

May Alcott Nieriker’s most potent legacy lives on not in her art, but rather in her travel writings, which often strikingly advocate for equal opportunities for women generally, and for women artists in particular. From her formative years May had been exposed to the need for women’s rights, both from practical and political perspectives. Her strong-willed mother Abigail May (1800–1877) struggled to find work outside the home in order to help pay the family’s bills, and as a result firmly supported her daughters’ desires to pursue careers, stating that “my girls shall have trades.”[62] Abigail additionally became an active voice in the women’s rights movement in Massachusetts, authoring in 1853 a petition to the state legislature which sought the extension of all civil rights to women, and in particular the right to vote.[63] The petition was rejected, but Abigail maintained her interest in the movement, and daughters Louisa and May took up the torch, each in her own way, to further the cause of women’s rights.[64]

This formative exposure to women’s rights, in addition to her own independent character, may help to account for some of the audacious autobiographical exploits related in Alcott Nieriker’s first articles, which originated in her letters to her family while she was abroad in Europe. Her first article, “A Trip to St. Bernard,” was one of those letters, and was to May’s surprise published in the Boston Daily Evening Transcript after her father submitted it to the editor.[65] In that narrative, May dramatically relates how she and four other women bravely ascended the famous pass in Switzerland during a thunderstorm, while their male companions had all turned back; furthermore, May was the only woman to do this on foot (the other women more conventionally rode mules). As she proudly noted later, “Everyone wonders at our performance.”[66]

Presumably encouraged by this first publication, and shrewdly responding to the popular interest in travel writing at the time,[67] Alcott Nieriker proceeded to write at least three articles in the summer of 1873, during her second period of study in London. One article, “How We Saw the Shah,”[68] similarly highlights May’s self-proclaimed “Yankee independence.”[69] The ostensible subject of the article, a chance sighting of the visiting Shah of Persia and his entourage, effectively captures the reader’s initial interest, but is soon overshadowed when May and her friends reach the river Thames. Overcome by “boating fever,” May boldly offers to take them for a row. “Horror fell upon” her friends at this bold proposal (Englishwomen only rowed in the “chaste seclusion of Papa’s grounds”), but May persisted and took to the oars by herself, with “all England watching on.”[70] As in the St. Bernard adventure, Alcott Nieriker demonstrates to her audience that travel abroad could bring women a greater degree of freedom than was possible at home, thereby encouraging women artists (and women in general) to follow suit.

In two other published articles, “A Hint to London Visitors” and “A Letter from an Art Student in London,”[71] May’s bold behavior shifts from social transgressions of a physical nature, to provocative criticism of the contemporary art world. In the “Hint to London Visitors,” Alcott Nieriker not only describes the opportunities to study J. M. W. Turner’s art in London, but laments that British watercolorists fail to emulate Turner’s “pure, transparent tones.” Additional criticism of contemporary British watercolor painting is found in the slightly earlier “Letter From an Art Student.” Alcott Nieriker also includes in that article some disparaging remarks about the lack of free opportunities to study art in America, now more apparent given her experiences in London: “I want a really good collection of the best pictures which shall be open to all. . . . When we get this, and schools such as we find here, then we need not run away from home and roam about gathering up the advantages of the Old World.” Indeed, the main thrust of the article is to encourage American women to go abroad and take advantage of the opportunities to study art in Europe: “Daily I long for an opportunity to tell many of the girls who are struggling to find the right help in America, how easy a thing it is to cross the Atlantic with no escort but one of the kind and courteous captains of the Cunard Line.”[72] What is particularly striking here is the advice to women to travel solo, which, although not unheard of, was still far from the norm and thus frowned upon by society.[73] Alcott Nieriker’s positive words and successful example may well have inspired women artists to come to London, for the American scholar and author Moncure D. Conway states in a November 1876 newspaper article that “the number of American ladies who come to England to study pictorial art increases.”[74]

During this same period in London, Alcott Nieriker also worked on a book-length travel narrative titled “An Artist’s Holiday.”[75] The manuscript consists of a series of vignettes which relate the adventures and insights of an American woman artist studying art in England. Alcott Nieriker’s strong desire to empower women of modest means to take action and travel abroad in their pursuit of an independent career as an artist is a recurring theme, as is evidenced in this passage:

But for a woman and an artist, particularly if not a good linguist, more can be learned & enjoyed in London at a moderate cost, than any spot I have ever seen or heard of. For not only does an Art Student have more precious use for her time than in sewing, trimming bonnets or housekeeping, but there is a large class of women with love for the beautiful, but of small means, who would gladly find a land where taste, accomplishments & education may be brought within their reach.[76]

May wrote some 309 pages, and then sent the manuscript to Louisa for editing and possible publication, but all that was published was one of the chapters, which Louisa submitted to the popular serial, The Youth’s Companion.[77]

Alcott Nieriker’s desire to encourage other American women artists to experience life abroad found its fullest expression in published form some six years later, after she and her husband had moved to Paris. May first mentions working on the manuscript that was to become Studying Art Abroad, and How To Do It Cheaply in a diary entry dated June 28, 1879:

Have been busy writing a little book of hints and suggestions to art students wanting to study in London, Paris, or Rome, which I think will prove useful to many who are perhaps about to make a first trip across the Atlantic. There is little art in it as I am not learned enough on the subject to write upon it, but have had some experience in knocking about alone in foreign cities, and think facts and figures are sometimes what people want more than any fine writing.[78]

May was well aware that there was a surfeit of travel narratives and guidebooks being published in this period,[79] yet smartly found her niche by gearing her publication to artists, the first such guidebook to do so.[80] Even more uniquely, she primarily directed her content to women artists, although the publication’s title does not betray this intention. At least one (presumably male) reviewer of the book took issue with the obscured female orientation of the book, writing, “Evidently it is the woman-student that the writer has in mind, and the title ought to say so.”[81] Although it is uncertain who determined the title of the guidebook, its gender-neutral nature likely enabled Alcott Nieriker’s artistic and social criticism (to be discussed below), safely ensconced within the more conspicuous travel advice, to reach a broader audience, which otherwise might not have bothered with a guidebook geared to women.

When Alcott Nieriker does identify her target audience in the introduction of Studying Art Abroad, she speaks not merely of women artists, but more specifically of those who, like her, could be characterized as “a thoroughly earnest worker, a lady, and poor, like so many of the profession, wishing to make the most of all opportunities, and the little bag of gold last as long as possible.”[82] By emphasizing the woman artist’s intentionality, frugality, and strong work ethic, Alcott Nieriker presents a positive ideal of the American woman abroad that stands in sharp contrast to the “indiscreet, husband-hunting, title-seeking butterfly”[83] evidenced in popular literature of the period, such as Henry James’s Daisy Miller (1878), and contemporary journal articles.[84] American women artists also had come under public attack in the press in this period, particularly by Paris correspondent Lucy Hooper. In an 1877 commentary, Hooper criticized these women for their purported lack of morality in studying the nude figure in mixed-gender studios, and accused them of repudiating “more appropriate” subject matter such as still-life.[85] Hooper’s comments were met with lengthy rebuttals from other American women in Paris,[86] and may have given Alcott Nieriker further impetus to advocate for the rights of women artists in her guidebook.

Studying Art Abroad (fig. 5) is an unillustrated, 87-page guidebook divided into five chapters focusing on three of the main destinations for American artists of the nineteenth century: London, Paris, and Rome.[87] In the introductory chapter the author states the guidebook’s goals, provides general encouragement for women desiring to study abroad, and offers experienced advice on ocean travel and what to pack. The next two chapters are devoted to London, the European city May knew best. London, in her opinion, was the best locus for aspiring watercolor painters as well as for artists interested in the decorative arts. Paris and its environs, the subject of the fourth chapter, is nevertheless given the greatest amount of attention due to its primacy as a venue for studying oil painting.[88] In the London and Paris chapters, Alcott Nieriker also informs readers as to where the frugal woman artist can find suitable lodging, art teachers amenable to teaching women, and the best art supply stores, based on her extensive experience abroad. She additionally notes where women can make savvy clothing purchases, including furs (London is best) and dresses (Paris, of course). The guidebook concludes with a comparatively brief chapter on Rome, which May characterizes as “the place for a student of sculpture rather than of painting.”[89]

Unlike other authors of nineteenth-century travel guidebooks, Alcott Nieriker makes few observations in Studying Art Abroad concerning the cultures she encounters abroad, no doubt to maintain her unique focus on the art world. But when she does make societal observations, her feminist outlook becomes strikingly apparent. In the first chapter, “En Route,” the artist stops in Warwick on her way to London and describes Leicester Hospital, ostensibly due to its picturesque late fourteenth-century architecture. She relates how the hospital was founded by the Earl of Leicester as a charity for twelve old men, and playfully imagines “twelve old men sitting comfortably smoking their twelve clay pipes”[90] in their twelve identical rooms. Yet then the tone turns more serious: Alcott Nieriker adds that upon talking with a local clergyman, she “took advantage of the occasion to ask why the present earl did not found a like comfortable home for twelve old women.”[91] If the clergyman responded, his answer goes unrecorded, nor does she return to the subject, apparently satisfied with having raised the question of gender inequity.

The absence of women in this English setting is countered by the prominence of strong women (and striking absence of men) experienced later in one of Alcott Nieriker’s descriptions of picturesque venues outside of Paris. A scene that caught her eye, although likely not for aesthetic reasons, was the weekly pig market in Dinan, France “where the women do the trading, fighting valiantly with an obstinate or enraged animal, and sometimes conquering only by mounting him, squealing loudly, on to their shoulders, and so bearing him off in triumph, amid the commendations of the crowd.”[92] Certainly Alcott Nieriker’s lengthy description adds an element of local color and humor to the guidebook, but in the context of her overall goal of empowering women, the passage vividly reinforces that women could succeed in traditional male roles when given the opportunity.

Equal opportunity for women in the art world is indeed one of the underlying themes of Studying Art Abroad. Alcott Nieriker for the most part maintains a positive tone, highlighting those institutions and ateliers that both welcome and challenge women artists. Yet she also cautions her readers against specific studios or institutions because she deems them inadequate or discriminatory. In her discussion of art training in London, for example, Alcott Nieriker is critical of the Female School of Art, which was then one of the foremost institutions in London for women artists,”[93] claiming that it is “rather elementary.” She bluntly adds that its annual exhibition “does not strike the visitor, from its standard of merit, as surprisingly creditable to the royal patroness,”[94] i.e., the Princess of Wales.

The issue of gender inequity in studio practices is especially evidenced in the Paris chapter. Like other women artists, May had come to Paris specifically to improve her figure drawing and oil painting techniques. But she soon found out that some painters refused to teach women altogether, while others, who did allow women in their studios, would invariably give them less attention and charge them a higher fee, since they were assumed to be wealthy amateurs. Alcott Nieriker had first raised the gender inequity issue in 1876, soon after her arrival in Paris. In a letter addressed to the Boston Evening Transcript, she openly criticized the popular Académie Julian, where women would encounter “very inferior advantages at more than double the cost charged the men, and in this as in so many other ways the injustice toward women who are trying to help themselves is very apparent.”[95] Instead, she recommended the studio of Edouard Krug, writing that “unlike [Thomas ] Couture & many other French painters he thinks women have as much right to study art as men, & give a fair promise of success.”[96] For reasons that we can only imagine, this letter seems never to have been published,[97] which is doubtlessly the reason she repeated her criticism in Studying Art Abroad, over which she had greater authorial control. Indeed, not much had changed in the intervening three years. In Alcott Nieriker’s view, Krug’s studio was still the best atelier for the female artist, given that other studios continued to be “overcrowded, badly managed, expensive, or affording only objectionable companionship.”[98]

Alcott Nieriker was not content merely to identify injustices in the Parisian art world, however. Following her commentary on studio conditions, she proposes that women artists band together and form their own atelier, outlining such steps as hiring a studio, choosing a critic, and engaging models.[99] Perhaps referring to a woman’s cooperative studio of which the American painter Elizabeth Gardner had been a part,[100] she notes that some women had attempted to do this in the recent past, but adds that they lacked a leader with the time to commit to the effort. Nevertheless, Alcott Nieriker asserts that it is “the only way open at present to successfully rectify the injustice of prices charged by Parisian masters for art instruction to women.”[101]

As a final means of encouraging her countrywomen, Alcott Nieriker comments on the successes of American women artists exhibiting in Paris, particularly Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) and Sarah Dodson (1847–1906).[102] She boldly claims that “in many instances” the paintings done by these and other American women are “far superior and, what is somewhat surprising, far stronger in style than most of that done by the men.”[103] May reinforces her argument by adding that their painterly achievements should be a source of pride for the United States, since even among the more populous French artists relatively few women had achieved renown. Of those women, Alcott Nieriker most highly regards the nineteenth-century animal painter Rosa Bonheur (1822–99), whom she praises for her “bold, almost masculine use of the brush, compared with the more delicate, even uncertain style of her brother, Jules Bonheur.”[104] Through these stylistic comparisons, the author demonstrates that, like the strong French women in the Dinan pig market, women artists could equal and even surpass the exploits of their male peers, thereby further encouraging American women to live out their dreams.

The Impact of May Alcott Nieriker’s Writings

Studying Art Abroad, and How To Do It Cheaply was published by Louisa May Alcott’s primary publisher, Roberts Brothers of Boston, in September 1879. Approximately 1,000 copies were printed, which seems to have been an average publication run for that firm,[105] and made available at fifty cents each. Today, relatively few original copies are extant in library collections,[106] perhaps an indicator that the pocket-size volume was put to practical usage. Even though it was ostensibly an unpretentious travel guidebook, Studying Art Abroad did receive critical attention, being reviewed in numerous sources, including the New York Times and The Nation.[107] Reviewers primarily focused on the guidebook’s novelty, practicality, and accessibility to a broader audience. For example, one commentator noted that although it was geared to women artists, the book was nevertheless “full of interest for the general reader.”[108] Only one reviewer objected to some of the more feminist-oriented content, stating his displeasure about Alcott Nieriker’s comment that women artists should be able to study from the nude model alongside male artists; nevertheless, he acknowledged that the section on Paris studios was “good, and calculated to set an enquiring pupil in the right direction.”[109] May was gratified by the positive press, noting in her diary for November 1879, just weeks before she died, “My little book is also published & the notices so far have been favorable & more than I could expect such an unpretentious work would be thought to deserve.”[110]

The exact impact of May Alcott Nieriker’s writings in the late nineteenth century is difficult to assess. It is true that many more American women artists went abroad to study in Paris in the 1880s and 1890s,[111] and art historians Erica Hirshler and Jacqueline Marie Musacchio have suggested that these artists likely relied upon Studying Art Abroad. [112] In addition, a related guidebook on The Art Student in Paris (directed to both male and female artists)[113] and numerous articles concerning American women artists abroad were published in the 1880s and 1890s,[114] which suggest that Alcott Nieriker’s publication may have set a precedent. Yet in terms of the Parisian studio situation, which May so vocally criticized, change was more elusive. The Académie Julian expanded its number of studios for women artists, but they remained crowded (one atelier had some 90 students), and fees remained discriminately higher even though instruction occurred less often.[115] However, it is interesting to note that Monsieur Julian had apparently become more sensitive to the needs of his foreign art students, likely to prevent further negative press. When American painter Cecelia Beaux left one of his ateliers after attending for a few months in 1888 and 1889, Julian is said to have done “everything in his power to ensure she said favorable things about his atelier.”[116]

Alcott Nieriker’s influence may be more noticeable in the creation of formal and informal women artists’ groups in Paris. The American Girls Art Club was founded in 1893 in order to help aspiring artists with reasonable lodging, an annual exhibition, and other forms of support so that they could concentrate on their creative endeavors.[117] More informally, women artists at the turn of the century in Paris are said to have “clubbed together on a cooperative system,”[118] sharing the expenses of hiring a model and allowing for less-crowded studio space, just as Alcott Nieriker had advised in Studying Art Abroad. Although her career was cut short, May Alcott Nieriker’s travel writings demonstrated to American women artists of limited income that it was possible to pursue their dream of international study and advancement. Then as now, it is difficult to imagine a reader not being inspired by May’s words of encouragement, her practical advice, and her passion for art.

This article is an extended variation on papers given by the author at the “Artists’ Writings 1850–Present” conference, Courtauld Institute of Art, London (June 2009) and the Feminist Art History Conference, American University (November 2013). I would like to acknowledge the superb assistance provided by the staff of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, and crucial financial support from the University of Minnesota, Morris, Faculty Research Enhancement Fund (FREF).

[1] The Peckham portrait was sent to the Alcott family in Concord, Massachusetts upon its completion, where it was given a place of honor in Orchard House and served as a bittersweet memorial of May, who died two years later. Little is currently known about Rose (or Rosa) Peckham Danielson (1842–1922), who studied art in Paris with her sister Kate between 1875 and 1878, and was a student of Jules-Joseph Lefebvre. Lois M. Fink, American Art at the Nineteenth-Century Paris Salons (Washington, DC: National Museum of American Art; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 379.

[2] In her essay, “My Girls” (1878), Louisa May Alcott writes of the splendid physical appearance of a group of young women as belonging to the “butterfly species”; but upon talking to the women she learns that they are in fact “industrious bees,” studying such professions as law, medicine, and art. Daniel Shealy, Joel Myerson, and Madeleine B. Stern, eds., Louisa May Alcott: Selected Fiction (Boston: Little, Brown, 1990), 328- 337. As Stern indicates (at page xxxvii) Louisa’s characterization of the artist is “clearly based on her sister May.”

[3] Caroline Ticknor, May Alcott: A Memoir (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1928).

[4] The following articles were published under May Alcott’s name: “A Letter from an Art Student in London,” Boston Evening Transcript, July 17, 1873, 6; and “A Hint to London Visitors,” Boston Evening Transcript, August 28, 1873, 6. “A Trip to St. Bernard,” published in the Boston Daily Evening Transcript, August 18, 1870, 2, is not credited to May, but directly corresponds to a letter that she wrote. Two of May’s compositions were published under her sister Louisa’s name in The Youth’s Companion in order to enhance publication sales: “How We Saw the Shah,” August 14, 1873; and “London Bridges,” July 23, 1874. These articles will be discussed further below.

[5] An extant copy of the manuscript, titled “An Artist’s Holiday,” is in the collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University (MS Am 1817/54).

[6] See, for example, the numerous references in Erica Hirshler, “At Home in Paris,” in Americans in Paris, 1860–1900, ed. Kathleen Adler, Erica E. Hirshler, and H. Barbara Weinberg (London: National Gallery, 2006), 57–114; and also see Frances Borzello, A World of Our Own: Women Artists Since the Renaissance (New York: Watson-Guptill, 2000), 125, 132–37.

[7] Sarah Burns and John Davis, American Art: A Documentary History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 778–80.

[8] Wendy Slatkin, The Voices of Women Artists (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1993), 127–32.

[9] The few scholarly sources on Alcott Nieriker or her guidebook to date are Judy Bullington, “Inscriptions of Identity: May Alcott as Artist, Woman, and Myth,” Prospects 27 (2002): 177–200; Debra A. Corcoran, “Another Dimension of Women’s Education: May Alcott’s Guide to Studying Art Abroad,” American Educational History Journal 31, no. 2 (2004): 144–48 (which primarily summarizes the guidebook’s contents); and Julia K. Dabbs, “The Multivalence of May Alcott Nieriker’s Studying Art Abroad, and How to Do It Cheaply,” Studies in Travel Writing 16, no. 3 (September 2012): 303–14. The author is currently working on a book project that will examine May Alcott’s travel writings in further depth.

[10] Slatkin, Voices of Women Artists, 126.

[11] There are currently no monographs on Alcott Nieriker, and she has been the subject of only one exhibition: “`Lessons, Sketching, and Her Dreams’: May Alcott as Artist,” held at the Concord Free Public Library Art Gallery, Concord, Massachusetts, November 3, 2008-January 30, 2009.

[12] Odell Shepard, Pedlar’s Progress: The Life of Bronson Alcott (Boston: Little, Brown, 1937), 292. “Bronson” was the name that Alcott preferred as an adult (John Matteson, Eden’s Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father [New York, W.W. Norton, 2007], 14), and is thus how he is often referred to in later sources.

[13] Louisa May Alcott, The Journals of Louisa May Alcott, ed. Joel Myerson and Daniel Shealy (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997), 92, 94.

[14] Martha J. Hoppin, “Women Artists in Boston, 1870–1900: The Pupils of William Morris Hunt,” American Art Journal 13, no. 1 (Winter 1981): 18.

[15] Erica E. Hirshler, A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston 1870–1940 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2001), 9. Unfortunately, when the School of Design was superseded by other institutions, such as the Lowell Free School, women were again left with a limited design curriculum and unsatisfactory studio conditions, according to May Alcott Nieriker, Studying Art Abroad, and How To Do It Cheaply (Boston: Roberts Bros., 1879), 28.

[16] Alcott, Journals, 100, 121. Louisa notes her sister’s studies with Hunt in Louisa May Alcott, The Selected Letters of Louisa May Alcott, ed. Joel Myerson, Daniel Shealy, and Madeleine B. Stern (Boston: Little, Brown, 1987), 123.

[17] Alcott, Journals, 100, 105, 158.

[18] Ibid., 162.

[19] For these comments, see Beverly Lyon Clark, ed., Louisa May Alcott: The Contemporary Reviews (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 61–66.

[20] May Alcott, Diary for 1863–1865, entry for October 18, 1863, MS Am 1817/57, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[21] Ticknor, May Alcott, 71.

[22] Alcott, Journals, 175.

[23] For the Alcott sisters’ letters home from this trip, see Daniel Shealy, ed., Little Women Abroad: The Alcott Sisters’ Letters from Europe, 1870–1871 (Athens and London: University of Georgia Press, 2008). Their series of adventures also would be commemorated by Louisa in her fictionalized 1872 travel narrative, Louisa May Alcott, Shawl-Straps (Boston: Roberts Bros., 1872).

[24] On this point, see Jacqueline Marie Musacchio, “Infesting the Galleries of Europe: The Copyist Emma Conant Church in Paris and Rome,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 10, no. 2 (Autumn 2011), accessed June 12, 2014, http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn11/infesting-the-galleries-of-europe-the-copyist-emma-conant-church-in-paris-and-rome. As Alcott Nieriker later writes in her unpublished travel narrative, “An Artist’s Holiday,” “Some would have thought it quite impossible for a lone woman born an enterprising American to have done many things recorded in these pages.” Quoted in Bullington, “Inscriptions of Identity,” 184.

[25] May Alcott to Anna Alcott Pratt, July 25, 1870, in Shealy, Little Women Abroad, 161. Shealy similarly notes how Alcott Nieriker’s travel experiences further developed her sense of maturity and independence. Ibid., lxxi.

[26] See Ibid., 161.

[27] May and her companion Alice sat on top of the carriage amid the baggage in order to better experience the scenery while travelling in northern Italy; as she writes afterwards, “But I wouldn’t have missed the enjoyment of the next few hours for all the ridicule in the world and the beauty of that drive from Luini to Lugano can hardly be overrated.” May Alcott to Abigail Alcott, October 8, 1870 in Shealy, Little Women Abroad, 236.

[28] May Alcott to Anna Alcott Pratt, May 30 1870, in Shealy, Little Women Abroad, 69.

[29] Thomas Charles Leeson Rowbotham (1823–75) was the son of watercolorist Thomas Leeson Rowbotham (1782–1853); together they had published two popular guides to landscape drawing and painting, The Art of Sketching from Nature, and The Art of Painting in Water-Colours. H. L. Mallalieu, The Dictionary of British Water-colour Artists Up to 1920 (Woodbridge, UK: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1976), 1:226.

[30] Alcott, Journals, 177.

[31] Ticknor, May Alcott, 101.

[32] Ibid., 187.

[33] Ibid., 122.

[34] May records receiving some $390 for her Turner copies in 1874, and $500 for one copy in 1875—the highest amount she records for any of her paintings, including original works. May Alcott Nieriker Cash Book, 1873–79, MS Am 1817 (55), Houghton Library, Harvard University. A color reproduction of one of Alcott Nieriker’s paintings after Turner can be found in Louisa May Alcott, Little Women: An Annotated Edition, ed. Daniel Shealy (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press / Harvard University Press, 2013), 334.

[35] As noted in Louisa May Alcott’s journal for March 1874, apparently Ruskin observed May painting her copies in the National Gallery, and “told her that she had ‛caught Turner’s spirit wonderfully.’” Alcott, Journals, 192. Ruskin’s praise was echoed in obituaries of May, for example in the Boston Evening Journal, January 1, 1880, 3 and the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean, January 17, 1880, 9, and in later writings concerning the artist, such as a New York Times article on “Louisa May Alcott’s Life and Letters,” April 9, 1898, and Clara Clement, Women in the Fine Arts (1904; repr. New York: Hacker Art Books, 1974), 6, entry for “Alcott, May.”

[36] Musacchio, “Infesting the Galleries of Europe.” See also Lisa Heer, “Copyists” in A Dictionary of Women Artists, ed. Delia Gaze (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997), 1:55–60 for a useful overview on the topic of women copyists.

[37] James Jackson Jarves, Art Thoughts: Experiences & Observations of an American Amateur in Europe (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1869), 217.

[38] On the Concord Art Center founded by May Alcott, see “Art in Concord,” Concord Freeman, July 24, 1875, 1; and Ticknor, May Alcott, 119–22. May was apparently assisted in this enterprise by Concord philanthropist William Munroe. Katherine Anthony, Louisa May Alcott (New York and London: Alfred A. Knopf, 1938), 235.

[39] Abigail May Alcott, Journal entry of September 22, 1876, in Ticknor, May Alcott, 126.

[40] Ticknor, May Alcott, 117.

[41] Ibid., 122. May echoes this sentiment in a letter to her mother, stating that she may need to stay in Europe for a year or more, for “I am awfully in earnest now and can do nothing at home for some time to come.” Ibid., 171.

[42] Alcott, Selected Letters, 218.

[43] Although May’s attendance at the Académie Julian is not indicated in any extant letters, her presence there in 1873 is noted in Peter H. Falk, ed., Who Was Who in American Art (Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1999), 1:76. However, that date is likely in error, given that there is no evidence that May went to France in 1873; additionally, Ticknor notes that May and Fanny Osbourne (later Stevenson) spent “many hours together at Julien’s [sic] studio,” which could only have happened in the fall of 1876. Ticknor, May Alcott, 219.

[44] For further background on the Académie and women artists, see Gabriel P. Weisberg and Jane Becker, Overcoming All Obstacles: The Women of the Académie Julian (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1999); Catherine Fehrer, “Women at the Académie Julian in Paris,” Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1100 (November 1994): 752–57; and Jo Ann Wein, “The Parisian Training of American Women Artists,” Woman’s Art Journal 2, no. 1 (1981): 41–44. The École des Beaux-Arts did not permit women artists to apply for entrance until 1897, after pressure from the Union des Femmes Peintres et Sculpteurs, a women artists’ organization in Paris. Tamar Garb, Sisters of the Brush: Women’s Artistic Culture in Late Nineteenth-Century Paris (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1994), 69.

[45] Alcott, letter to the Boston Evening Transcript, November 25, 1876 (unpublished), MS Am 1817(60), Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[46] Krug (1829–1901) was an award-winning history and portrait painter. In addition to being praised by Alcott Nieriker in Studying Art Abroad, the Krug atelier also received positive press in Alice Greene “The Girl Student in Paris,” Magazine of Art 6 (1883): 286–87.

[47] For example, whereas in the 1860s (after the American Civil War) there were approximately 85 American artists total in Paris (and presumably many fewer female than male) as noted by Lois M. Fink, “American Artists in France, 1850–1870,” American Art Journal 5, no. 2 (November 1973): 34, by July 1877 there were some 150 American women artists studying there. “American Women as Art Students in Paris,” Boston Daily Advertiser, July 12, 1877, 4.

[48] Ticknor, May Alcott, 138–39.

[49] Alcott’s Nature morte is listed in the Paris Salon de 1877 catalogue (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1977), 3. The still life currently is on display in Orchard House, Concord, Massachusetts. See further on this painting, Ticknor, May Alcott, 179–82, 192–93, 198–99.

[50] Ticknor, May Alcott, 199.

[51] Ibid., 182.

[52] These tallies are derived from information provided in Lois Fink, “List of American Exhibitors and Their Works, 1800–1899,” in American Art at the Nineteenth-Century Paris Salons, 313–409. My thanks to research assistant Rachel Kollar for her help in compiling these statistics.

[53] Ticknor, May Alcott, 240.

[54] This achievement was noted in the Washington, DC National Republican, December 31, 1877, 2; see also May’s comments in Ticknor, May Alcott, 245–46.

[55] Alcott, Journals, 209, 212n2.

[56] May summarizes the development of this somewhat surprising relationship in a letter to her Aunt Bond, May 14, 1878, MS Am 2745/62, Houghton Library, Harvard University. In that letter, May explains that “the right man had never asked her” previous to her encounter with Nieriker, and that as a single woman she was “finding sufficient satisfaction in her painting.”

[57] A few nineteenth-century examples of professional women artists who set aside their careers upon marriage include Emma Conant Church and Susan Macdowell Eakins. For literary reflections of this dilemma, see, for example, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps’s The Story of Avis (1877), and the unfinished novella by Louisa May Alcott, Diana & Persis, ed. Sarah Elbert (New York: Arno Press, 1978) which was based in part on May’s experiences. For a useful scholarly discussion of portrayals of women artists in literature in this period, see Deborah Barker, Aesthetics and Gender in American Literature: Portraits of the Woman Artist (Lewisberg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2000); and specifically on Diana & Persis, see also Natania Rosenfeld, “Artists and Daughters in Louisa May Alcott’s Diana and Persis,” New England Quarterly 64, no. 1 (March 1991): 3–21.

[58] Ticknor, May Alcott, 278. Italics in original.

[59] Writing in 1878, May states that she has “seven studies on exhibition in Paris, two just finished for Lille, a panel in the Manchester gallery, two in London, and an order ready for America.” Ticknor, May Alcott, 281.

[60] The original Salon painting of La Negresse is in the possession of May Alcott Nieriker’s European descendants (per Jan Turnquist, director of Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House, conversation on July 22, 2012); a smaller version, perhaps the study for the Salon painting, is at Orchard House, Concord, Massachusetts. The painting is listed in the catalogue for the Paris Salon de 1879 (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1977), 189 under “Nieriker, Mme. May,” and is illustrated in Fink, American Art at the Nineteenth-Century Paris Salons, 195.

[61] The exact cause of Alcott Nieriker’s death on December 29, 1879 is uncertain; what is known is that she suffered from a fever for weeks before her death, possibly caused by a childbed infection. Eve LaPlante, Marmee & Louisa (New York: Free Press, 2012), 267. Her daughter, Louisa May (nicknamed Lulu), was sent to Concord after May’s death to be raised by her aunt Louisa, according to her parents’ wishes. Following Louisa’s death in March 1888, Lulu returned to live with her father in Zurich, Switzerland.

[62] Abigail May Alcott, My Heart is Boundless, ed. Eve LaPlante (New York: Free Press, 2012), 88.

[63] LaPlante, Marmee & Louisa, 168. A more complete transcription of the petition can be found in Madeleine B. Stern, L.M. Alcott: Signature of Reform (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2002), 209–10.

[64] Louisa May Alcott regularly assisted the women’s rights movement, both nationally and locally, and was the first woman in Concord to register to vote (albeit limited to a school board election) in 1879. May heartily approved of Louisa’s actions, writing from Paris: “I wish I was there to have [a] finger in all the good pies & give my energy to this womans [sic] movement which interests me greatly.” May Alcott Nieriker Diary, August 6, 1879, MS Am 1817/58, Houghton Library, Harvard University. A useful summary of Louisa’s feminist writings and activities can be found in Gregory Eiselein and Anne K. Phillips, eds., The Louisa May Alcott Encyclopedia (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001), 352–54, s.v. “Women’s Movement” by Kathryn Tomasek.

[65] The letter is published in Shealy, Little Women Abroad, 132–37, and after being edited by her father, was published in the Boston Evening Transcript of August 18, 1870, 2 (“A Trip to St. Bernard”). May is not identified directly as its author; instead, the editor’s preface asks readers to guess which of the “Little Women” was involved (and it is clear from the content of the letter that it is not Louisa). May later writes to her family that she found it “very funny” that the letter was published, and if she had known, she could have described the adventure much better. May Alcott, letter to Abigail and A. Bronson Alcott, August 30, 1870, in Shealy, Little Women Abroad, 210.

[66] May Alcott to the Alcott Family, July 10, 1870, in Shealy, Little Women Abroad, 135.

[67] As Mary Schriber has noted, approximately 1700 books on foreign travel were published in the United States prior to 1900. Mary Schriber, Writing Home: American Women Abroad 1830–1920 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997), 47. See also Harold F. Smith, American Travellers Abroad: A Bibliography of Accounts Published Before 1900, 2nd ed. (Lanham, MD and London: Scarecrow Press, 1999).

[68] “How We Saw the Shah” was published under Louisa May Alcott’s name in The Youth’s Companion, August 14, 1873, and that misattribution has continued to the present day. See, for example, The Sketches of Louisa May Alcott, ed. Gregory Eiselein (Forest Hills, NY: Ironweed Press, 2001), 238. Ticknor indicates that the text was written by May (Ticknor, May Alcott, 111), and a letter of August 14, 1873 from Daniel Ford of The Youth’s Companion to Louisa confirms that the content is indeed May’s authorship (“Papers of Louisa May Alcott,” MSS 6255, Box 1, folder 80, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library). The misattribution likely was intentional, for, as Ford acknowledges, Louisa’s name would sell more copies than that of her sister.

[69] May Alcott, “How We Saw the Shah,” in Ticknor, May Alcott, 115.

[70] Ibid., 115–16.

[71] “A Letter from an Art Student in London” was published in the Boston Evening Transcript on July 17, 1873, 6, with the byline “May Alcott, June 22, 1873”; excerpts are found in Ticknor, May Alcott, 104–9. “A Hint to London Visitors” was published in the Boston Evening Transcript on August 28, 1873, 6, with the byline “May Alcott, August 3, 1873.”

[72] May Alcott, “A Letter from an Art Student in London.”

[73] See on this point Schriber, Writing Home, 24, 156–59.

[74] M. D. Conway, “London Letter,” in the Boston Daily Advertiser, November 8, 1876, 1.

[75] An extant copy of the manuscript, with some pages in Louisa May Alcott’s handwriting, is in the collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University (MS Am 1817/54). See further on this text, Bullington, “Inscriptions of Identity,” 183–84; and Judy Bullington, “The Artist-as-Traveler and Expanding Horizons of American Cosmopolitanism in the Gilded Age” (PhD diss., Indiana University, 1997), 111–22.

[76] May Alcott, “An Artist’s Holiday,” MS Am 1817/54, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[77] In a journal entry for September 1879, Louisa notes that she had printed May’s “nice little letters of An Artist’s Holyday.” Alcott, Journals, 217. However, at this point I have only found one of the chapters published, as an article entitled “London Bridges,” published in the Youth’s Companion on July 23, 1874, with Louisa credited as the author.

[78] May Alcott Nieriker Diary for 1878–79, entry for June 28, 1879, MS Am 1817/58, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[79] Alcott Nieriker, Studying Art Abroad, 5–6.

[80] Certainly, other artists, such as the British painter Anna Mary Howitt, had written about their experiences abroad (An Art Student in Munich, 1853), but the distinction here is that their publications were more of the descriptive, narrative type, rather than being practical handbooks.

[81] Review of Studying Art Abroad, and How to Do it Cheaply, Nation, November 27, 1879, 372–73.

[82] Alcott Nieriker, Studying Art Abroad, 6–7.

[83] Ibid., 49.

[84] See for example Alice Bartlett, “Some Pros and Cons of Travel Abroad,” Old and New, October 1871, 433–42; and Lucy H. Hooper, “American Women Abroad,” Galaxy, June 1876, 818–22. Excerpts from both articles can be found in Henry James, Daisy Miller, ed. Kristin Boudreau and Megan Stoner Morgan (Buffalo: Broadview Editions, 2012), 193–94, 177–79.

[85] Hooper’s letter, printed in an as-yet-unidentified New York newspaper, was quoted directly in anonymous articles titled “Women Students in Paris: Art Studies from the Nude,” New York Times, July 8, 1877, 2; and “American Women as Art Students in Paris,” Boston Daily Advertiser, July 12, 1877, 4.

[86] “Women Students in Paris: Art Studies from the Nude,” New York Times, July 8, 1877, 2; and “American Women as Art Students in Paris,” Boston Daily Advertiser, July 12, 1877, 4. May Alcott was aware of Hooper’s comments, as she writes in a letter to her mother (July 26 and 28, 1877): “I think there will be several answers to old Hooper as her letter made a great stir among my crowd and caused much indignation.” MS Am 2745/53, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[87] As Alcott Nieriker notes, Munich was another popular destination for American artists at the time, but given her brief visit there (in 1871) and her disappointing experience in its gallery, she decided to refrain from writing about it. Alcott Nieriker, Studying Art Abroad, 7.

[88] Ibid., 42.

[89] Ibid., 77.

[90] Ibid., 15.

[91] Ibid., 16.

[92] Ibid., 63.

[93] See further on this institution, Deborah Cherry, Painting Women: Victorian Women Artists (London and New York: Routledge, 1993), 58–59; and F. Graeme Chalmers, Women in the Nineteenth-Century Art World: Schools of Art and Design for Women in London and Philadelphia (Westport, CT and London: Greenwood Press, 1998), 49–64.

[94] Alcott Nieriker, Studying Art Abroad, 29.

[95] May Alcott, letter to the Boston Evening Transcript, November 25, 1876, MS Am 1817(60), Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[96] Ibid.

[97] Unlike May’s other articles, there is no corresponding newspaper clipping of this writing that was saved, based on my research at Houghton Library, Harvard University. Searches of the Boston Evening Transcript and newspaper indices have not turned up any results, either.

[98] Alcott Nieriker, Studying Art Abroad, 48.

[99] Ibid., 49.

[100] Gardner’s participation in the co-op studio is briefly discussed in Charles Pearo, “Elizabeth Jane Gardner and the American Colony in Paris,” Winterthur Portfolio, 43 (Winter 2009): 288; and in Madeleine Fidell-Beaufort, “Elizabeth Jane Gardner Bouguereau: A Parisian Artist from New Hampshire,” Archives of American Art Journal 24, no. 2 (1984): 3.

[101] Alcott Nieriker, Studying Art Abroad, 50.

[102] Dodson, although little-known today, was an established painter of classical and biblical subjects, as well as of landscapes. Chris Petteys, Dictionary of Women Artists: An International Dictionary of Women Artists Born Before 1900 (Boston: G.K. Hall, 1985), 203. She had ten paintings accepted into the Paris Salon during her career, including two paintings in 1879, the year in which Alcott Nieriker was writing. Fink, American Art at the Nineteenth-Century Paris Salons, 338.

[103] Alcott Nieriker, Studying Art Abroad, 51.

[104] Ibid., 52.

[105] Based on the Printing & Binding Records of Roberts Brothers [publishers], MS 2004M-90, Houghton Library, Harvard University. It does not appear that the guidebook was reprinted in later years. Some 43 new titles were published by Roberts Brothers in 1879, and although it was not among the largest publishing houses in the United States, it was considered “among the choicest,” emphasizing quality over quantity of titles. Raymond Kilgour, Messrs. Roberts Brothers, Publishers (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1952), 1–2.

[106] A recent search of the WorldCat database surprisingly indicates that only about 40 original copies of Studying Art Abroad are found in libraries worldwide.

[107] Studying Art Abroad was reviewed in the New York Times, October 19, 1879; in the Nation, November 27, 1879, 372–73; and in the Portland Daily Press, November 21, 1879, 17, among others.

[108] Clipping of book review (unidentified author or source), found in May Alcott Nieriker Diary for 1878–79, MS Am 1817(58), Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[109] Review of Studying Art Abroad in Nation, November 27, 1879, 372.

[110] May Alcott Nieriker Diary for 1878–79, MS Am 1817(58), Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[111] According to Kirsten Swinth, by 1888 there were approximately 1,000 American artists participating in Parisian academies or studios. Kirsten Swinth, Painting Professionals: Women Artists and the Development of Modern American Art, 1870–1930 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 39. According to Pamela H. Simpson, approximately half of all American artists were female as of 1890. Pamela H. Simpson, review of Painting Professionals: Women Artists and the Development of Modern American Art, 1870–1930, by Kirsten Swinth, Woman’s Art Journal 25, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2004): 52. Thus, approximately 500 women artists in Paris in 1888 would reflect a substantial increase from June 1877 when 150 American women artists were said to be in Paris. “American Women Art Students in Paris,” Boston Daily Advertiser, July 12, 1877, 4.

[112] Hirshler, A Studio of Her Own, 76; and Musacchio, “Infesting the Galleries of Europe,” n. 6.

[113] The Art Student in Paris was a 52-page pamphlet published in 1887 by the Boston Art Students Association.

[114] For which see Swinth, Painting Professionals, 37–38.

[115] Fink, American Art at the Nineteenth-Century Paris Salons, 136; and Swinth, Painting Professionals, 49.

[116] Gabriel P. Weisberg, “The Women of the Académie Julian,” in Weisberg and Becker, Overcoming All Obstacles, 52. Beaux was initially disappointed in the quality of the other students’ work, and subsequently disenchanted with the instruction she received. Alice C. Carter, Cecilia Beaux: A Modern Painter in the Gilded Age (New York: Rizzoli, 2005), 77, 100.

[117] Swinth, Painting Professionals, 54–55.

[118] Clive Holland, “A Lady Art Student’s Life in Paris,” Studio (1904) quoted in Charlotte Yeldham, Women Artists in Nineteenth-Century France and England (New York: Garland, 1984), 1:60.