The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

A Missing Question Mark: The Unknown Henry Ossawa Tanner

Race remains at the heart of Henry Ossawa Tanner studies. Though he would have wished it not to be so, the issue of Tanner's African American identity defined him in the late nineteenth century and continues to be the criterion by which twenty-first-century audiences appraise his legacy. Tanner struggled and sacrificed to become a recognized and accomplished painter of spiritual narratives, while we would have him also be a reluctant hero—the artist who against all odds overcame social barriers to shine at the Paris Salons, see his work purchased by the Musée du Luxembourg, and be compared critically with James McNeill Whistler. Tanner's path to artistic success was indeed marked by instances of insult and injustice, and his career ascendancy was a remarkable feat. He lived his life, however, one that was driven by a commitment to the creation of art, in conflict with the hopeful expectations of many of his contemporaries. Tanner's conflict, one of enormous pain and complexity, was born of the fact that in his personal adult life he walked a fragile line between his whiteness and his blackness; in France, he systematically worked to remove race from the equation of his life.

In 1914 the poet and art critic Eunice Tietjens wrote an article provisionally titled "H. O. Tanner" that she had hoped to publish in the International Studio.[1] She sent Tanner a draft of the article along with a letter, which read in part:

If there is anything in the article that you don't like or don't think is true I'm afraid you'll have to expostulate to the editor, if he accepts it [the article]. The "if" seems large to me tonight, but then I'm tired . . .

Do write to me what you think of it. Here's luck to us![2]

Tanner, in his rely to that letter, stated that the one problem he had with her article was contained in its last paragraph which reads:

In his personal life Mr. Tanner has had many things to contend with. Ill-health, poverty and race prejudice, always strong against a negro, have made the way hard for him. But he has come unspoiled alike through these early struggles and through his later successes. Simple and sincere like his canvases he has quietly followed his own instinct for beauty and has already given to the world many unforgettable paintings, while there are yet many years of work before him.[3]

Tanner's objection was to the inference that he is a Negro. In the most comprehensive study done to date on the artist, the 1991 Philadelphia Museum of Art catalogue accompanying the exhibition of the same name, Henry Ossawa Tanner, Dewey Mosby characterizes Tanner's response to Tietjens's article as being revelatory of "the complicated nature of Tanner's own thinking about race."[4] Tanner's reply begins:

May 25—1914

Dear Mrs. Tietjens—

Your good note & very appreciative article to hand I have read it & except it is more than I deserve, it is exceptionally good. What you say, is what I am trying to do, and in a smaller way am doing it (I hope).

The only thing I take exception to is the inference in your last paragraph—& while I know it is the dictum in the States, it is not any more true for that reason—

You say "in his personal life, Mr. T. has had many things to contend with. Ill-health, poverty, and race prejudice, always strong against a negro"—Now am I a Negro? Does not the 3/4 of English blood in my veins, which when it flowed in "pure" Anglo-Saxon men & which has done in the past, effective & distinguished work in the U.S.—does this not count for anything? Does the 1/4 or 1/8 of "pure" Negro blood in my veins count for all? I believe it (the Negro blood) counts & counts to my advantage—though it has caused me at times a life of great humiliations & sorrow—unlimited "kicks" & "cuffs" but that it is the source of all my talents (if I have any) I do not believe, any more than I believe it all comes from my English ancestors.

I suppose according to the distorted way things are seen in the States my curly blond curly-headed little boy would be a "negro."[5]

Tanner's statement "I believe it (the Negro blood) counts & counts to my advantage" has been interpreted as "clear confirmation of his [Tanner's] pride in his own roots."[6] When this letter was cited in the Philadelphia catalogue, however, the transcription contained a significant mistake. Instead of a period—"Now am I a Negro."—Tanner actually placed a question mark at the end of that sentence: "Now am I a Negro?" This one mark completely changes the meaning of Tanner's reply. Whereas he did not discount his African American blood, he emphasized that he is more white than black: three-quarters white, perhaps as little as one-eighth "pure" Negro. Furthermore, according to Tanner, neither his whiteness nor his blackness accounted for his talent.

The phrase "Now am I a Negro?" is profound evidence that Tanner understood himself to be, by virtue of genealogy and self-definition and not according to the "distorted way things are seen in the States," not black. It was, he had come to conclude, a matter open to discussion. Yes, his African American blood counted, but again in his words, did the three-quarters of his English blood "not count for anything?"

The question mark in Tanner's original letter was also left out of the first important book on Tanner, Marcia M. Mathews's 1969 biography.[7] Almost a quarter of a century later, in 1993, the late art historian Albert Boime saw and accurately recorded the question mark in Tanner's text. His interpretation of the letter, however, misses Tanner's complex self-identification in favor of presenting him as ethnically unambiguous. Boime contends that it was Tietjens's characterization of the "psychology" of Tanner's pictures that elicited the artist's "explosive response."[8] That contention is wrong. Tanner wrote to Tietjens: "the only thing I take exception to is the inference given in your last paragraph" that he is a Negro.[9] More from Tanner's letter:

Please don't imagine, that any of this criticism of American ways applies in the least, to you [Tietjens] or yours. It absolutely does not & there are many others also. But the last paragraph made me want to tell you what I think of myself—that I am glad I am what I am. For the same reason that a Swede hates to be called a Norwegian, & Danes to be called a Swede, a Scotchman to be called an Englishman & etc.—He is no better than the other, but sometimes he thinks he is as my chickens thought the earth was made for chickens & not for turkeys—Of course I shall not write Mr. Lane but, should the article be accepted if you would recommend that your [PAGE MISSING]

It might be like what happened when my Lazarus was bought by the French Government. It was telegraphed to the States "A Negro sells picture to French Government." Now a paper in Baltimore wanted a photo of this "Negro" of course they had none, so out they go & photograph the first dock hand they came across & it looked like maybe some of my distant ancestors when they were come from Africa.[10]

Boime writes that Tanner "makes it clear at the end of his draft that he wishes to be identified ethnically as black."[11] Actually, it seems Tanner was arguing that the word "Negro" should be removed.

Tanner's letter, when it continues after the missing page, provides the reason that Tanner asked that Tietjens's paragraph be removed—because "It might be like what happened when my Lazarus was bought by the French government": a photo of any Negro would serve to identify him.

In this critically important document, Tanner's characterization of American thinking on race as "distorted" can be seen as a reference to the infamous "one-drop rule," according to which his son, he writes, would be "Negro."[12] Tanner obviously does not agree with this view. He does not believe the one-drop rule should apply to his son and, by extension, it should not apply to him, either.

Current art historical writings claim that Tanner's life work is essentially black in construct and culture. Paul Richard, an art critic writing in 1969 on a Tanner retrospective then on view in Washington, DC, pointedly questioned that premise:

He [Tanner] must have suffered. His blackness must have been thrown up at him a dozen times a day, yet he never wrapped himself within it. He would have regarded the dashikis and bush cuts of today [1969] with more embarrassment than pride. In time he came to exaggerate the whiteness of his ancestors and he did it without shame, for he never considered himself particularly black. "Now am I a Negro?" he once wrote. "Does not the 3/4 of English blood in my veins . . . which has done in the past effective and distinguished work in the U.S.—does not this count for anything? Does the 1/4 or 1/8 of "pure" Negro blood in my veins count for all . . . ?"

That same question, plaintive and ambiguous—"Now am I a Negro?"—echoes throughout the galleries of the current show.

Those who visit it search for something. They look for Tanner's blackness for some sign of that rich creative Afro-American heritage to which they're told these unfamiliar paintings so significantly contribute.

It does not show.[13]

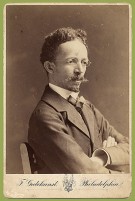

Henry Tanner's (fig. 1) birth is recorded as June 11, 1859.[14] His parents were Benjamin Tucker Tanner and Sarah Miller Tanner, a former slave whose mother had sent her children north on the Underground Railroad. Sarah was one of eleven children; six of these were fathered by a freedman named Charles Miller, and five were fathered by the white plantation owner.[15] The latter may have been Tanner's grandfather, as Henry was born fair-skinned and with reddish hair, although these traits could be also attributed to Miller, who was of mixed race.

One of the more poignant cruelties Sarah Tanner endured came shortly after Henry's birth. With her one-year-old son in tow, she had gone from her home in Alexandria, Virginia, into Washington to shop. At day's end, a storm came up and she attempted to ride the streetcar that connected the two cities. African Americans were not allowed to ride the cars, but it was snowing out, so Sarah pulled a veil over her face and exposed Henry's light face. Sadly, she was discovered midway on the journey. A man approached her, pulled up her veil, and said, "Who, what have we here a nigger, stop the car." Sarah and child were put out into the cold.[16] Tanner himself recorded this incident later in life, writing "I never knew this story till I was a grown man and we were in our Diamond Street house in Phila near East Park. I left the house immediately and it took several hours walking in among the trees and under the night skies to cool the heat and hatred that surged in my bosom."[17] The insult to his mother was literally unforgivable. Again, in Tanner's words: "May God forgive them for even at this distant day it is hard for me to do so." Tanner's anger at the white men on the streetcar persisted into his old age. So, too, did his full awareness that his mother used his own skin, which was so like theirs, to try and keep him warm—in spite of the risk of humiliation.

Tanner's father (fig. 2), who became a high-ranking clergyman, has been described as "stoic, circumspect and austere."[18] Photographs of the elder Tanner, showing his intense gaze and formal posture, support such a characterization. Bishop Tanner was an indefatigable worker both for the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church and for the cause of abolition, preaching and writing with intensity and conviction. He wrote that the skin of the Negro was "written by the finger of God, it is more enduring than the stones of Sinai. It remains, and will remain the badge of our suffering, the triumph."[19] He served as the longtime editor of the AME Church's Christian Recorder and in 1884 completed a comprehensive history of the denomination. The totality of his commitment to abolition is evidenced in the middle name he gave his firstborn—Ossawa—after the town of Osawatomie, Kansas, home of John Brown. Henry Ossawa Tanner thus carried with him a constant reminder of his father's great cause.

However, Henry Ossawa Tanner did not visually embody the source of the abolitionist struggle, that is, dark skin. And here begins a complex story of conflict and contradiction: Tanner is light enough to be presented as white by his mother, yet he is the son of a charismatic preacher who saw black skin as "the triumph." What we cannot know with certainty, but must consider in the examination of the artist's life, is the nature of Tanner's understanding of his own blackness as he forged his identity within the crucible of American racism. We do know that Henry Ossawa Tanner chose a career path very different from his father's and practiced it professionally and permanently in a land far from America.

Tanner recounted the beginnings of that career in his charming and highly sanitized autobiographical article, "The Story of an Artist's Life."[20] He recounts that he and his father were walking through a park when Tanner was thirteen years old and encountered an artist painting out of doors. The young Tanner was mesmerized, deciding there and then to become a painter. After a hapless try at self-teaching, it was clear to him that he needed lessons. Of his early attempts to find an instructor, Tanner made this troubling statement:

No man or boy to whom this country is a land of "equal chances" can realize what heartache this question [of finding instruction] caused me, and with what trepidation I made the rounds of the studios. The question was not, would the desired teacher have a boy who knew nothing and had little money, but would he have me, or would he keep me after he found out who I was.[21]

Tanner feared being rejected by white teachers because he is black. The part of Tanner's statement that calls for deeper consideration is this: "Would he keep me after he found out who I was." The meaning here is not altogether clear, as Tanner could be describing different scenarios. The first is that Tanner had contacted studios by letter (telephones did not yet exist), and had likewise been invited to visit by letter. Then, when he presented himself, he was refused. As Tanner wrote: "I went to Mr. —. He 'had other pupils.'"[22]

Alternatively, he may have feared being accepted as a student but jettisoned if the instructor "found out who I was," that is, an African American. Tanner's recollection reaching back forty years describes, however inadvertently, his earliest attempts to use his skin to navigate a world controlled by whites. As a young boy, he was so desperate for art instruction that he was willing to allow potential teachers to draw their own conclusions about his physical traits.

One of Tanner's early Philadelphia art instructors, C. H. Shearer, knew Tanner was African American and not only accepted him but encouraged him. Tanner recalled that he could never appreciate enough Shearer's kindness, and how Shearer helped to reduce Tanner's bitterness:

He [Shearer] would remove, at least for a time, that repressing load which I carried, a load which was as trying to me as that carried by poor Pilgrim. I was extremely timid, and to be made to feel that I was not wanted, although in a place where I had every right to be, even months afterward caused me sometimes weeks of pain. Every time any one of these disagreeable incidents came into my mind, my heart sank, and I was anew tortured by the thought of what I had endured, almost as much as by the incident itself.[23]

Like countless other African Americans, Tanner suffered greatly from racist torment. Unlike most, though, Tanner was not always perceived to be black by those he encountered. The "load" he carried, then, must have been made heavier by a heightened awareness of the fundamental irrationality of color-based discrimination: if he did not appear black but was nonetheless hated when discovered to be, was it really "blackness" that was hated or something deeper? How was a young Henry Tanner to reconcile himself to being black in the same way that other African Americans did? As he moved from situation to situation, he carried not only a "load" but a constant nervous anticipation—would he be instantly insulted and hurt, would such treatment come later, or would it not come at all, if only he kept quiet?

In 1879, Tanner entered the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts where he was enrolled on and off through 1885. His study under the fiercely independent Thomas Eakins (1844–1916) was pivotal: he came to understand the discipline required to lead an artist's life and had regular exposure to fully professional work. During the 1880s Tanner explored landscape (his first ambition was to be America's greatest marine painter), animal subjects (his next ambition was to be America's greatest animal painter), and genre painting.[24]

The fullness of these years, however, was marked by shameless cruelty from fellow students. At the academy, Tanner's racial status was known. Interestingly, he was described by the American printmaker Joseph Pennell (1860–1926) as an "octoroon," which in the parlance of the time meant one-eighth Negro.[25] Pennell, who was a student at the academy when Tanner arrived, took the one-drop rule to heart. In a memoir written years later, Pennell relates the torment Tanner endured: "Then he [Tanner] began to assert himself and, to cut a long story short, one night his easel was carried out into the middle of Broad Street and, though not painfully crucified, he was firmly tied to it and left there. And this is my only experience of my colored brothers in a white school; but it was enough."[26]

Tanner wrote that the memory of these tortures was worse than the experiences themselves, in short, the ongoing mental anguish exceeded specific instances of racism. Being black inside a white world had a price, Tanner learned, one that would be exacted at every turn in ways both blatant and subtle. The effect on Tanner of intimidation and brutality should not be underestimated: the racists of the world, and in America they were seemingly endless, could thwart one's career. Doors could be closed, opportunities denied. Not every instructor, not every colleague would be as supportive as Eakins (himself an unusual social progressive, responsible for bringing the practice of drawing from live nude models to the Pennsylvania Academy). Tanner could have a career in art in America, but it was clear to him that it would be forever fraught with obstacles.

Tanner chose early to confront these obstacles, but his initial efforts were unsuccessful. He opened a photography gallery in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1889 which proved to be a miserable experience and one injurious to his always fragile health. Tanner accepted the common belief that mountain air was curative, and he spent that summer in the Highlands, the lush mountainous region southwest of Asheville, North Carolina. While there, he made small, outdoor watercolor studies that resulted in the large, impressive oil Mountain Landscape, Highlands, North Carolina (fig. 3), a work that summarized the artist's formative education and early career ambitions. His experiences in Atlanta must have been somewhat spirit crushing: he made no money, became sick again, and saw no future there. However, why pick the remote and sparsely populated Highlands as a place to heal from apparent nervous exhaustion brought on by an ill-conceived business venture? The mountain air, of course, was the medical attraction, and the immaculate scenery was an incentive as well. The Highlands may have been recommended to him by the important friend and patron he made while in Atlanta, Bishop Joseph Crane Hartzell, a white man, of the Methodist Episcopal Church (not to be confused with the AME Church).

The Highlands had also been advertised as a place where there were no African Americans (fig. 4).[27] Nonetheless, by the time Tanner visited in 1889, some African Americans were to be found. Still, his time in the Highlands may have been the first instance in Tanner's life when he could move about freely and unharrassed (fig. 5), painting in open air as he pleased precisely because he did nothing to advertise that fact that he was African American and, as he knew, no one—unlike his fellow students in Philadelphia—knew of his family background.

Tanner returned to Atlanta in the fall and taught at Clark Atlanta University. He knew, as did so many late-nineteenth-century American artists, that for his career to advance European study was required. That study was funded by his Atlanta patrons Bishop and Mrs. Hartzell, who arranged an exhibition of Tanner's work and subsequently bought every painting in the show. Tanner arrived in Paris in 1891 and enrolled at the Académie Julian, the privately run studio school popular with Americans and an alternative to the government-sponsored Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Many of Tanner's experiences in France followed a familiar pattern for the aspiring art student: he refined his proficiency in drawing at the academy; he labored over a large painting for the all-important Salon; he painted out of doors in the countryside (specifically, in Pont-Aven and then Concarneau); and enjoyed the camaraderie of fellow artists. One of these was the Utah artist James Taylor Harwood (1860–1940), who painted Tanner into a charming luncheon-on-the-grass scene that included Harwood's new wife, Harriet Richards, while all three were staying in Pont-Aven (fig. 6).

Harwood had first arrived in Paris and the Académie Julian in 1888. He had returned to Utah Territory briefly, then went back to Paris to marry Richards on June 25, 1891. He and his new wife had planned to stay in Concarneau over the summer, but they found it crowded and headed for the smaller resort of Pont-Aven. Once there, the Harwoods met Tanner, and their subsequent friendship was recalled in Harwood's memoirs:

Soon after we got settled a foreign-looking young man was placed opposite us at the table, but we noticed his French had a very decided American twang, delivered with some spluttering and stumbling. We soon learned his name was H. O. Tanner, the now very famous Negro artist. We became very friendly with him and never knew his race 'til a long time afterwards.[28]

This recollection provides our first incontrovertible evidence of Tanner's willingness to conceal the African American component of his extraction. He and Harwood, artists and both far from home, most definitely would have talked about their backgrounds. Harwood was a non-Mormon from Utah, with a strange and colorful story to tell. He had been to the California School of Design, whereas Tanner had been to the Pennsylvania Academy. Both enjoyed photography, both were nondrinkers (Harwood's aversion to alcohol was its impractibility; he espoused no religion). They must have had numerous story-filled conversations into the late, quiet hours at Pont-Aven. And, there was the lovely painting Harwood made in 1891 of his wife, Harriet, and Tanner having lunch on the grass (posed with wine and cigarettes to make the scene appear cosmopolitan). How could Harwood not know Tanner's race "'til a long time afterwards," which would not have been weeks, but years?

Tanner must have never shared this information with Harwood. He told Harwood that he was a Methodist, but not that he was a member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He did not talk about being abused by fellow students at the Pennsylvania Academy, or that his mother had gone North on the Underground Railroad. Instead, Tanner allowed their friendship to develop predicated on their mutual interests in art alone. To do this, he must have suppressed information about his race and his family. Tanner was able to control how he presented himself to the Harwoods from the time of their first meeting because of his experience in the Highlands of North Carolina; he had done this before.

Had Harwood been aware of Tanner's African American status, he would have treated his fellow painter differently. When he first crossed the Atlantic on his way to Paris in 1888, Harwood and other American artists amused themselves with the daily harassment of a black man aboard the ship, the details of which Harwood recounted in a letter home. That letter includes these ominous words: "The Darkie got it again last night. Marvin told him through the day we were going to make a white man out of him. Before he went to bed M. sprinkled flour all over the bed. The boys say they will give him a send off to night, as it is the last."[29]

Harwood did not provide details of what the "send off" consisted of, though we may assume it was not pleasant. Harwood referred to the group torment of the black man as "foolin'" and happily reported that "I laughed till I was almost sick."[30] Had Harwood known of Tanner's background, Harwood would not have painted Tanner lounging on the grass with his, Harwood's, new bride.[31] As it was, both Harwood and Tanner spent what was very important time together, as they were both working on their all-important Salon submissions, and they must have critiqued each other's work. Both submitted paintings to the Paris Salon in 1892; Harwood's was accepted, Tanner's was not.[32]

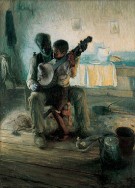

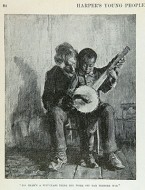

Tanner returned home in 1893, once again suffering from ill health—this time from a life-threatening bout with typhoid fever. Back in America, he completed his iconic image, The Banjo Lesson (fig. 7).[33] The artist's turn to African American subject matter on his return to Philadelphia coincided triply with his convalescence, a period of work for the AME church, and with being back in a country where racist caricatures were the order of the day. It was also a time when Tanner was working to save money toward a planned return to Paris. Tanner had already supplied illustrations for Harper's Young People in 1888, and, once again in need of money, he took on new assignments. It was this illustration work specifically that led in a straight line to the creation of his best-known painting.

The direct inspiration for TheBanjo Lesson was the short story, "Uncle Tim's Compromise on Christmas," by Ruth McEnery Stuart (1849–1917), which appeared, with Tanner's illustration, in Harper's Young People in 1893.[34] Stuart describes the tender story of a grandfather who has but one valuable possession—a banjo—and he makes a gift of it to his grandson on Christmas morning. The "compromise" is that they will both share it. Tanner based his illustration for "Uncle Tim's Compromise" (fig. 8) on a photograph he himself staged (fig. 9).[35] His illustration (most likely a grisaille) was a near replica of the photo. It even includes the shadow that appears in the photo on the wall to the left, but not the canvas behind the figures in the photo since, of course, Uncle Tim would not have had a canvas leaning against the wall of his cabin.

While his illustration was rather perfunctory, Tanner must have been moved by Stuart's sympathy for her characters. Her prose, although in stereotypical dialect, nonetheless evoked genuine pathos. Tanner's composition illustrates the following passage:

The only thing in the world that the old man held as a personal possession was his old banjo. It was the one thing the little boy counted on as a precious future property, and often, at all hours of the day or evening, old Tim could be seen sitting before the cabin, his arms around the boy, who stood between his knees, while, with eyes closed, he ran his withered fingers over the strings, picking out the tunes that best recalled the stories of olden days that he loved to tell into the little fellow's ear. And sometimes, holding the banjo steady, he would invite little Tim to try his tiny hands at picking the strings.[36]

In The Banjo Lesson, Tanner masterfully elaborated on the core idea present in his illustration, taking visual cues straight from Stuart's prose. The moonlight from the window that Stuart describes as a "long panel of light upon its [the cabin's] smoke-stained wall" forms the backdrop for Tanner's old man and young boy whose poses are fully derived from the text in Stuart's story.

The simple instrument in the photograph became the equally simple-looking banjo in the black-and-white illustration. In the painting, though, the instrument is elaborate, with gold tuning knobs on a finely carved headstock and ivory inlay on the fretboard. How would the impoverished grandfather have owned such an instrument? What internal logic was Tanner following that allowed him to create a scene where all was poor and humble, save for this instrument? Again, he took his conception directly from Stuart's story. In the following passage, the grandfather explains to his grandson how he came to own such a fine instrument:

But having once started to speak, the old man was seldom brief, and so he would continue: "It's true dis ole banjo she's livin' in a po' nigger cabin wid a ole black marster an' a new one comin' on blacker yit. (You taken dat arter you' gran'mammy, honey. She warn't dis heah muddy brown color like I is. She was a heap purtier and clairer black.) Well, I say if dis ole banjo is livin wid po' ignunt black folks, I wants you ter know she was born white.

Don't look at me so cuyus, honey. I know what I say. I say she was born white. Dat is, she descended ter me f'om white folks. . .

Why, boy, dis heah banjo she's done serenaded all de a'stocercy on dis river 'twix' here an' de English Turn in her day. Yas, she is. An' all dat expeunce is in 're breast now; she 'ain't forgot it . . .

An' yer know, baby, I'm a-tellin' you all dis," he would say, in closing, "caze arter while, when I die, she gwine be yo' banjo, 'n' I wants you ter know all 'er ins an' outs."[37]

Surely Tanner would not have missed the grandfather saying that the boy's grandmother was "purtier and clairer black," and that the grandson takes after her. This dynamic is represented In Tanner's photograph: the adult portraying the grandfather in the photo is not clearly black, yet the boy is. Therefore, Tanner interpreted "clairer black" as more purely black, not light-skinned. In The Banjo Lesson, this issue of the grandfather's diluted color is lost. He becomes "clairer black," and it is his grandson who lightens.

In the latter half of 1893, when Tanner was working first on his illustration for "Uncle Tim's Compromise" and then on The Banjo Lesson, he wrote (using the third person): "To his mind many of the artists who have represented Negro life have only seen the comic, the ludicrous side of it, and have lacked sympathy with and appreciation for the warm big heart that dwells within such a rough exterior."[38] This statement gives us some idea of what Tanner might have said when he spoke at the Congress on Africa at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. In these few words, Tanner recognizes the preponderance of stereotypical imagery in American art, a catalogue of caricature that was but one manifestation of the monolithic American racist mind set.[39]

Some historians have understood Tanner's TheBanjo Lesson as a rejoinder to those comic and ludicrous images of Negro life; some, indeed, believe that The BanjoLesson subverted American genre painting.[40] However, knowing the literary source of Tanner's painting—Stuart's short story—gives us a very different sense of Tanner's motivations.[41] He was moved by the sentiment of this Christmas story and the valuable lessons it imparted about teaching, sharing, and continuing traditions. In giving masterful form to these important values, he simultaneously countered prevailing stereotypical imagery by transforming simple virtues into the extraordinary.

It is critical to recognize, too, that in The Banjo Lesson, Tanner hewed visually to the narrative of "Uncle Tim's Compromise on Christmas," a narrative written by a white woman as a children's story for Harper's Young People, a magazine that had a white audience. Knowing now that Tanner's painting originated as a work for hire, we may examine how it relates to standard late-nineteenth-century white narratives of the black experience. The painting does not represent as dramatic a departure from certain of those narratives as previously assumed, including those painted by Tanner's teacher, Thomas Eakins. Eakins's Negro Boy Dancing (fig. 10) shares with The Banjo Lesson similar pedagogical aspects: the older teaching the younger. Tanner's magisterial oil painting is free of caricature and the same could be argued for Eakins's smaller-scaled watercolor.

Revised interpretations of The Banjo Lesson are urgently needed precisely because it remains central to our cultural and artistic understanding of Tanner and his legacy. Typical of recent judgments is that "[Mary] Cassatt's Banjo Lesson pictures are as white as Tanner's is black."[42] Another art historian writes that Tanner's BanjoLesson is "a document of protest, liberation, and transformation."[43] Given the verifiable source of The Banjo Lesson, Tanner's own subsequent treatment of it, and—most important—Tanner's own racial self-identification, these judgments are now subject to modification.

Despite the importance today of The Banjo Lesson, Tanner not only never claimed it as a work of African American genre, after he became well known he never even mentioned it—or showed it. According to Darrell Sewell: "In his autobiography and in other articles and interviews, Tanner never mentioned The Banjo Lesson or The Thankful Poor, and perhaps even more noteworthy, he seems not to have requested them for exhibitions of his work, including his first retrospective in New York in 1908."[44]

More than one admirer of the artist wished he had remained in America and served as an exemplar of expertise and accomplishment for African Americans, but Tanner was drawn back to Paris, where, as he later wrote, he was surrounded with "helpful influences."[45] One of those "helpful influences" was the French Salon where TheBanjo Lesson was accepted in 1894. Although even recent scholarship has questioned whether TheBanjo Lesson was actually in the Salon, Tanner himself made this perfectly clear in a formal letter (Tanner uses "we" in referring to himself) of May 1894 to none other than Frederick Douglass:

A plan is now afoot to present the "Bagpipe Lesson" to Hampton Institute. As to its artistic merit the fact that it was well hung in the very representative exhibition held at the Penn. Academy of Fine Arts during the winter of 93 & 94, and also that it was one of forty chosen to make an illustrated catalogue (no. 329) speak volumes for it, also the fact that before leaving Paris we were given a letter of commendation by Benjamin Constant and Jean Paul Laurens, and our picture "The Banjo Lesson" is now in Paris at the Salon speaks somewhat for our ability.[46]

The importance of Salon recognition for emerging artists cannot be overestimated, and for Tanner it was a clear signal of professional confirmation. In 1895 he painted the first version of Daniel in the Lion's Den (now lost) that was accepted at the Salon of 1896 and awarded an honorable mention. This honor revived Tanner's dreams and, in his own words, he "went to work with a new heart."[47] Though Tanner never returned to African American subject matter, it has been suggested that he transferred his sensitivity to social issues into his religious work.[48] Of Daniel, Dewey Mosby observed: "Informed by his family background and his desire to represent profound issues of black life, Tanner now looked to the Bible for some of his most vital themes."[49]Tanner's Daniel does evoke themes of imprisonment, trial, and endurance, but it is no longer certain that TheBanjo Lesson established in the artist a desire to represent issues of black life that would be sustained in subsequent work.

Tanner's Salon recognition gained the attention of the prominent American collector Rodman Wanamaker, whose support would accelerate the artist's professional success. Wanamaker sponsored Tanner's travel through Palestine and Egypt in that year, as he would again in 1899. This patronage is not without significance, as it tied Tanner to the support of a white man's money and inextricably linked him to the prevailing aesthetic and expectations of Wanamaker's social class and milieu. Wanamaker's support was not based on the few African American paintings Tanner had made in Philadelphia, but rather on the religious imagery he made in Paris that echoed aspects of Whistler, Rembrandt, and Symbolist poetry.

In 1897 Tanner's La Résurrection de Lazare (The Resurrection of Lazarus) was awarded a third-class medal and was purchased by the French government for the Musée du Luxembourg. Tanner became, and would remain, the subject of numerous art world articles in America—almost always identified in some way as a "Negro artist." This constant need for the American art community to see Tanner as black was noted in an 1897 article praising the Lazarus, one that also pointedly discussed how un-African Tanner looked:

His father is a minister, now a bishop in the colored Methodist Church. How much a proportion of colored blood is in Mr. Tanner's veins I am ignorant, for he has one of the faces that shows few of the familiar traits. His skin is as fair as the average descendent of the Latin race, and it is only a second scrutiny that hints of his African descent.

This fact has really nothing to do with his work. Among the charming notices that have been written in the French journals concerning the success of this last picture [the Lazarus] not one has alighted on this, to Americans, rather picturesque fact, partly because the artist has kept himself so secluded in his studio that few know him personally, and, perhaps, too, because in France we are more accustomed to clever men of African descent.[50]

The sympathetic author of this review, who found Tanner's Lazarus to be superior to many of the canvases by the "big names," apparently tried to interview the artist for her article and, again apparently, it seems Tanner would not talk about himself. For biographical information, she relied on a friend of Tanner's:

Mr. Tanner cannot be interviewed, because he has nothing to say; that is, nothing about himself. He has no skill at grasping at pictorial incidents in his life. He cannot be convinced that the reading public cares a rap about him, and at the moment he prefers to talk of Jerusalem to anything else. Nevertheless, an acquaintance of several years and admirer of his undoubted talent may be permitted to introduce him to American readers.[51]

Since Tanner had "nothing to say . . . about himself," the reporter must have learned of his African ancestry from this third party. Tanner's "admirer" also shared with the Herald writer Tanner's opinion of his father, Bishop Tanner: "Mr. Tanner affirms that he has the best father on earth, and when he wished to study art, which seemed the pursuit of a chimera that time, this father gave him every support and encouragement in his power."[52]

Having just won a third-class medal at the 1897 Paris Salon and, beyond that, having that picture purchased by the French government would seem the perfect occasion for an artist to grant an interview and revel in the publicity. Not Tanner. He was content to have an acquaintance speak on his behalf. We might cite a combination of his shyness, humility, and the possibility that he did not wish to address the issue of race, which might take the focus off his artistic achievement. Unfortunately, his race— this "picturesque fact"—remained a fixture in American articles on Tanner's Parisian progress. However much he longed to be considered an artist first, the press routinely qualified him—and thus his achievements—as "Negro."

In 1898 Tanner met Jessie Macauley Olssen (1873–1925), a white opera singer from San Francisco (fig. 11). The very next year, Tanner did something that an African American man in America never could: he married her. In America an interracial couple would have been not only unthinkable, but in most states illegal. How did Tanner summon the courage, for courage is the appropriate word, to make this bold move?

Among the factors to be considered is love. Tanner loved her, and Jessie wrote to him in 1899: "Come to me."[53] He did. Then, too, they married in London[54] and planned to remain in Europe, so that whatever sanctions existed in America would not apply to them. A third factor is that Tanner did not particularly like to socialize in groups and, significantly, he and his new wife did not appear to be interracial. There would be few situations, if any, giving rise to confrontation or requiring accountability. In America, Tanner was the great "Negro artist" in news articles.[55] In France, in his day-to-day life, he was the French-speaking Monsieur Tanner, a painter from America.

Tanner was able to take a white woman for a wife in France because by this time he had refashioned his racial identity. He lived his daily life well outside the parameters of what it meant to be black in America.[56] By first presenting himself as not necessarily black ("Now am I a Negro?"), he could elicit different, more egalitarian treatment from other Americans in Europe as well as from European colleagues. His was a problematic racial strategy, though one that left no clear racial identification for himself and one that always left a door open for discrimination.

Seeing himself as mostly white did not, simply put, always work. The American artists living in Paris knew of his ancestry, and it mattered. Tanner presented himself to them as having only "a touch" of Negro blood, but that was enough for them to treat him with disdain despite Tanner's Salon success. American artist Guy Pène du Bois (1884–1958), a member, as was Tanner, of the American Art Association in Paris, recalled this anecdote from 1905: "Tanner, who had a touch of Negro blood, once had the innocence or the folly to permit his name to be put up for election to the house committee. He failed to get even the vote of his sponsor. This little corner of Paris, like its spittoons, was definitely American."[57]

Surely Tanner was humiliated by this incident. As Pène du Bois noted, it was surprising Tanner would have attempted to hold an elected office among Americans—even among his alleged friends and colleagues—but this "folly" makes sense knowing that Tanner was living in between his whiteness and his blackness. That is, Tanner knew that the contours of racial discrimination were different in Paris as he felt his way forward, ever testing the limits of his freedom. Because he had won medals at the Salon and his work had been purchased by the Musée du Luxembourg, his peers were not in a position to publicly question his artistic merit. That question had been officially decided. Instead, no matter what his standing in the French art world, they could let him know by way of a unanimous vote that he was not really welcome in their group.[58]

The most dramatic demonstration that Tanner did not "consider himself particularly black" came in 1917, not long after his letter reciting that he was three-quarters English, when he enlisted at age fifty-eight in the American Red Cross (fig. 12). As John F. Hutchinson, author of Champions of Charity: War and the Rise of the Red Cross, notes, "Once the United States entered the war and national fund-raising drives were organized, Red Cross patriotism reached a fever pitch."[59] Tanner, living in a country where the war was being waged, was not unaffected by a sense of duty, yet he most certainly knew that the American military was racially segregated. So, too, was the American Red Cross—once African Americans were allowed to serve. Again according to Hutchinson: "It is scarcely surprising that the Red Cross mirrored the social divisions of American society (and of the army) by having separate "colored branches" that provided assistance to the "colored" units of the armed forces: Some soldiers—just like some citizens—were evidently more equal than others."[60]

Tanner enlisted with the American Red Cross not in America, of course, but in France. He obtained a letter of introduction from Walter Hines Page who was the United States ambassador to England, working in London. Page's letter reads in full:

My dear Colleague:

This introduces you to Mr. H. O. Tanner, an American whom I have long known, a painter of great distinction, and a man of philanthropic impulses and activities. He will explain to you an interesting scheme that he wishes to further in connection with convalescent hospitals.[61]

In the United States, Page had been the editor of World's Work and published Tanner's "Story of an Artist's Life" in that periodical in 1909. Page, a friend to Booker T. Washington, is often cited as an exemplary social progressive of the era. However, his progressivism needs to be contextualized, as was done in a brief literary review by Roger D. Launius for the Journal of Negro History:

The portrait [of Walter Page] that emerges is not that of a high-minded reformer who seeks to make America a utopia, rather it is that of a man who blended expediency with morality, pragmatism with idealism. Page's style of Progressivism, therefore, possessed a certain shadowy side that arose out of cultural misconceptions and long-standing notions. Consequently, Page was not in favor of open immigration because it would, among other repercussions, dilute pure nationalism. He disliked many labor unions because they destroyed the freedom of the marketplace. And he did not see the need for full equality of the races because of the "inherent inferiority" of non-whites.[62]

Indeed, Page was very much a man of his times on the issue of presumed black inferiority. His personal letters are spotted with remarks typical in their casual but clearly deeply embedded racism.

Why, then, did Page provide Tanner with a letter of introduction to the American ambassador in France? Inconsistent as his progressivism could be, Page nonetheless believed in education for all races and economic classes in America, a stance represented by his editorial efforts for the World's Work. Having known Tanner since at least 1909 when Tanner wrote for him, and knowing full well that Tanner was African American, Page would have been impressed with Tanner's dramatic success in Paris. And Page of course supported the efforts of the Red Cross and the Allied forces. These reasons combined would have been sufficient for him to give Tanner a letter of introduction. However, the ardent Anglophile Page may also have been open to Tanner's argument that he, Tanner, was three quarters English and "did that not count for anything."

Tanner took this letter to ARC headquarters in Paris in late 1917, and enlisted as an "American," which he was, and bypassed the issue of race.[63] At that time, blacks were not authorized to serve in the American Red Cross. Even black nurses could not serve until June 1918 and, despite that authorization, were turned away as late as October of that year. When, because of the desperate need for nurses, the American Red Cross finally authorized them to serve, it required them to wear badges that clearly identified them as African American, "so that there was no possibility of assigning them to duty without reference to their color," and their records were maintained in a "separate file."[64] Racism was an issue within the American Red Cross, whether at home or abroad even as late as 1942, when the ARC had a policy of segregating African American blood for transfusions.[65] In 1917, therefore, Tanner's race, had it been known, would have prevented him from serving alongside white Americans.

Yet serve he did, as a lieutenant in charge of a program to raise much needed vegetables. It is submitted here that Tanner's success in working with white officers was because they did not know his racial background. A handwritten recollection by Tanner describes a disturbing racist incident that occurred at Neufchâteau in 1918. In Tanner's words:

It had been a rather gay dinner when Capt R—— continuing his accounts of a trip to the front which had fired us all said "but we will have to kill several of those niggers down home before we will be able to get them back in their place." Now I had not known that the —— Regiment which they had been talking about was a N—— regiment.

Capt R—— and I had seen I to I on many subjects and had become quite friends which surprised me—as I knew the first time I met him that he was from the South. He came from Miss—— and like a good many people from the South he talked a great deal on religion. After the remark called forth by I have forgotten what he continued quite a tirade against the Negro. There was little said for or against his leading remark, as nearly all forgot to apply any of Christ's Spirit upon a subject in which their own prejudices and weaknesses were concerned . . . [Capt R] was I know as blind as when Isaac blessed Esau.[66]

This recollection is telling in the extreme. Given our extensive knowledge of the historical horrors of racism in the American South, it is next to impossible to envision a Southerner of that time having dinner with an African American, war or no war, especially when the service in question—the American Red Cross—initially barred blacks before being officially segregated. Had Captain R known Tanner's identity, surely Tanner would have been confronted with very different, direct, and personal aggression. As it was, Tanner sat silently through the tirade. Captain R, he knew, "was . . . as blind as . . . Isaac." The story Tanner relates makes sense if and only if Captain R was not aware of Tanner's racial identity.

We do not know the thoughts that went through Tanner's mind at this dinner, and it would be presumptuous to speculate. We do know, however, that he could serve in the American Red Cross as a lieutenant because he did not look African American. This was a conflict with no resolution. Tanner enjoyed near-unprecedented freedom for a black American of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but he did so only by living away from America and by not foregrounding the African American aspect of his heritage. The personal pain this caused Henry Ossawa Tanner cannot be known, though we might on sustained reflection sense its enormity: he could not paint African American subject matter; his family never visited him in France; he was aloof from the Harlem Renaissance;[67] and no letters between him and his father survive. His professional and personal life were circumscribed and defined by the complexities associated with his self-styled racial identity.

Henry Ossawa Tanner embraced the role of the artist as defined in late-nineteenth-century Europe, replete with its conventions, conformities, and aesthetic. Tanner's expatriation to France in 1894 coincided with his abandonment of African American subject matter. No reason of persuasive explanatory power has, to date, been given. It is reasonable to reconsider his shift to painting exclusively religious subjects as mirroring his repositioning of himself in the world. He had left America and its one-drop-rule glass ceiling, freeing himself from America but simultaneously losing the pulse of its day-to-day realities. Just as that culture could no longer impose its strictures on him, so, too, could he no longer claim to be an intimate of that world. Gradually redefining himself as no longer black ("Now am I a Negro?") but also not as white, as no longer American but not French, Tanner was left to paint spiritual narratives not of his own time or experience. Along the way, even his devout Methodism gave way to a religious catholicity that saw truth unbounded by dogma and the presence of God stretching through the universe and "extending to worlds other than our own." At the end, he believed that man should not submit passively to his fate, and he had not.[68] However, it is not altogether clear now that in resisting fate, he was reconciled to the choices he had made. His achievements, ultimately, were grounded in a life of complex compromise lived in between his blackness and his whiteness, a compromise forced on him by racism.

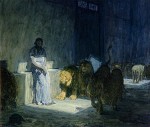

Among the spiritually compelling images Tanner made in Europe is his later version of Daniel in the Lions' Den (fig. 13), painted during the War years. We see the Old Testament prophet Daniel, half in light, half in shadow, his hands bound, and surrounded by lions that seem uninterested in his presence. The idea that Tanner sublimated racial issues into religious themes is not without merit, and, of course, there is Tanner's own justification for making religious imagery:

It is not by accident that I have chosen to be a religious painter. I am very glad to say that I have not been forced to paint any pot boilers for twenty years and I never do them. I paint the things I see and believe. I have no doubt an inheritance of religious feeling, and for this I am glad, but I have also a decided and I hope an intelligent religious faith not due to inheritance but to my own convictions. I believe my religion. I choose religious subjects not primarily because I believe they will interest people, nor because I consider them saleable. I am very glad if they do interest the people, and certainly am glad to sell them. Yet, I have chosen the character of my art because it conveys my message and tells what I want to tell to my own generation and leave to the future.[69]

Tanner's wish for his own legacy is clear: he hoped for us to experience the Christian faith through his art. Instead, Tanner and his paintings continue to be critically examined primarily through the lens of racism. In his 1914 letter to Eunice Tietjens, Tanner made several points clear—he acknowledged his African American blood and that it counted to his advantage; he cited his English ancestry and asked pointedly whether or not that ancestry "counted for anything"; and he judged the American view of race as "distorted." Generations before the identity politics of our own time, Tanner wished to define himself independently, rejecting no aspect of his heritage. One hundred years after his birth, Americans remain preoccupied with race, and historians of American art with Tanner's sense of his blackness. Tanner's ethnicity has consistently been considered as incontrovertible fact, but the artist was not so sure. His question about himself—"Now am I a Negro?"—a challenge in 1914, continues to this day.

[1] On Tietjens, see her memoir, The World at My Shoulder (New York: MacMillan, 1938).

[2] Eunice Tietjens to Henry Ossawa Tanner (hereafter HOT), May 12, 1914, in Archives of American Art, Washington, DC, Henry Ossawa Tanner Papers, (hereafter Tanner Papers), roll D306, frame 0113.

[3] "H. O. Tanner," draft for an article by Eunice Tietjens, 1914, Tanner Papers, roll D307, frames 1975–76.

[4] Dewey F. Mosby, "Reflections on Race, Public Perception, and Critical Response in Tanner's Career," in Mosby and Darrell Sewell, Henry Ossawa Tanner (New York: Rizzoli in association with the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1991), 13. (hereafter Mosby and Sewell, Tanner). Tanner's letter to Eunice Tietjens, May 25, 1914, is a draft letter of three pages (incomplete), handwritten in pencil, in the Tanner Papers. This document viewed by the author in Washington, D.C., 11 July 2007. The final page appears to have been torn in half. The letter in its entirety may be viewed online at Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/searchimages/images/item_7211.htm (accessed September 2, 2009).

[5] HOT to Tietjens, Tanner Papers.

[6] Mosby, "Reflections on Race," 13.

[7] Marcia M. Mathews, Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969), 143.

[8] Albert Boime, "Henry Ossawa Tanner's Subversion of Genre," Art Bulletin 75, no. 3 (September 1993): 418.

[9] Jennifer J. Harper also identified Tanner's clear intention in his letter. Harper, "The Early Religious Paintings of Henry Ossawa Tanner: A Study of the Influences of Church, Family, and Era," American Art 6, no. 4 (Autumn 1992): 83: "In a letter of 25 May 1914 to the author of an article describing his career it is clear that the typically sensitive and tactful artist was offended by her references to him as a Negro."

[10] HOT to Tietjens, Tanner Papers.

[11] Boime, "Subversion of Genre," 418.

[12] For an overview of the one-drop rule and its application, see F. James Davis, Who Is Black? One Nation's Definition (College Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991). The author thanks Dr. Naurice Frank Woods, Jr., faculty and former chairof the African American Studies Department, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, for directing him to these and other sources. In addition, Dr. Harrell B. Roberts, formerly the director, Counseling and Testing Center, at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, has consulted with the author on psychological issues related to identity, passing, and the convoluted perceptions of "race" and ethnicity—past and present—that continue to confound our understanding of the human personality. The author further thanks Dr. George Dimock, professor of art history, and Dr. Janine Jones, professor of philosophy, both of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, for their support, encouragement, and insights. Dr. Fronia Simpson and Robert Alvin Adler provided thoughtful editing.

[13] Paul Richard, "About the Henry Tanner Hangup," Washington Post, August 3, 1969, in Tanner Papers, roll D307, frame 1086.

[14] No birth certificate, civic or familial, exists for Henry Tanner. He recorded his birth date on his passport, a copy of which is in Tanner Papers, roll D307, frame 1644.

[15] For an account of Sarah Tanner's origins, see Rae Alexander Minter, "The Tanner Family: A Grandniece's Account," in Mosby and Sewell, Tanner, 23–24. Also see Tanner's biographer, Marcia M. Mathews, who records that Tanner's maternal grandfather was of mixed racial origin. "On his mother's side Henry Tanner was the grandson of Charles Jefferson Miller, born in 1808, the mulatto son of a white planter in Winchester, Virginia. Charles Miller left Virginia in 1846 for the free state of Pennsylvania, taking his family [which would have included Tanner's mother, Sarah] with him in an oxcart." Mathews, Tanner, 6.

[16] Ibid., 10.

[17] Ibid.; Also see Tanner Papers, roll D306, frames 1611–12, for the recording of this story in Tanner's own hand; quote at frame 1611.

[18] Minter, "Tanner Family," 24.

[19] Quoted in Mosby, "Reflections on Race," 11. For a biography of Bishop Tanner, see William Seraile, Fire in His Heart: Bishop Benjamin Tucker Tanner and the A.M.E. Church (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1998).

[20] HOT, "The Story of an Artist's Life," World's Work 18 (June–July 1909), 11662.

[21] Ibid., 11663.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid., 11665.

[24] Ibid., 11663.

[25] Joseph Pennell, The Adventures of an Illustrator: Mostly in Following His Authors in America and Europe (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1925), 54.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Samuel Truman Kelsey, The Blue Ridge Highlands in Western North Carolina (Greenville, SC: Daily News, Pamphlet and Law Press, 1876), as reprinted in Gert McIntosh, Highlands North Carolina . . a Walk into the Past (Birmingham, AL: Birmingham Printing and Publishing Company, 1996), 48. The author thanks Richard Gantt, Department of Art and Art History, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, for this reference. Gantt has recently done original research on Tanner's time in the Highlands that awaits publication.

[28] From James Taylor Harwood, "A Basket of Chips," typescript copy of the artist's memoirs, 42, author's possession. Also see Robert S. Olpin, ed., A Basket of Chips: An Autobiography by James Taylor Harwood (Salt Lake City: Tanner Trust Fund, University of Utah Library, 1985).

[29] James T. Harwood to Harriett Richards, August 1888, written aboard ship en route to Southampton, England. Envelope postmarked Southampton, September 6, 1888, possession of the author. This letter is one of a large cache of letters given to the author by Willard Harwood, the artist's son. The other artists involved were Guy Rose (1867–1925), Eric Pape (1870–1938), and Frederick Marvin (dates unavailable).

[30] Harwood to Richards, August 1888.

[31] One would like to think that Americans were better behaved in France than at home, that their racism was tempered by being abroad. For evidence against this view, see the anecdote in this article regarding Tanner and his hopes to serve in the American Art Association in Paris.

[32] Harwood recalled he painted his first Salon picture, Preparations for Dinner, while on his honeymoon in Pont-Aven, and that their company then was "mostly Tanner." He notes that both he and Tanner entered the Salon of 1892, when Preparations was stamped to compete for honors. Harwood further recalled: "Twelve years later we [the Harwoods] returned to France. Tanner had then won the highest honors given to an American, and the picture I sent to the Salon on my return was rejected." Harwood, "A Basket of Chips," 42. For a biography of Harwood, see Will South, James Taylor Harwood (Salt Lake City: Utah Museum of Fine Arts, 1988). Tanner did not recall his time with Harwood in Tanner's "Story of An Artist's Life." His first Salon entry might have been an early version of The Bagpipe Lesson that he dated as being from "the next summer" at Concarneau (following his summer at Pont-Aven), which would have been the summer of 1892. The word "Concarneau" is conspicuously inscribed on the front of the painting. It is possible, too, that his work of 1891 is not extant. In any case, Tanner certainly knew about the Salon and worked toward acceptance there in 1891. In his article, "Story of An Artist's Life,"he implies that he did not know of the existence of the Salon until his return to Paris after the summer of 1891. Tanner never mentions Harwood in any letters or documents that survive in the Tanner Papers.

[33] Various conflicting information surrounds The Banjo Lesson. Recent claims have stated that it was painted in Paris, others say Philadelphia, while very recent scholarship shows that Tanner painted more than one version of TheBanjo Lesson, adding to the confusion. On The Banjo Lesson being painted in Paris, see Guy C. McElroy, Facing History: The Black Image in American Art, 1710–1940 (Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art in association with Bedford Arts, Publisher, 1990), 102. McElroy repeats the misconception found originally in Mathews, Tanner, 37, that The BanjoLesson was painted after sketches done during Tanner's time in the Highlands. Sewell identified Philadelphia as "the more likely locale for its production" in Mosby and Sewell, Tanner, 119. Sarah Burns, author of "Whiteface: Art, Women, and the Banjo in Late-Nineteenth-Century America," in Picturing the Banjo, ed. Leo Mazow, exh. cat. (University Park, PA: Palmer Museum of Art/ Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006), 82, contends there were two versions of The Banjo Lesson, and that the one exhibited at the 1894 Salon "may have been the one now in the Hampton Institute." The present article contends that there was only one oil on canvas, that it was painted in Philadelphia, and that it was indeed the one in the Salon of 1894.

[34] Ruth McEnery Stuart, "Uncle Tim's Compromise on Christmas," Harper's Young People 15, no. 736 (December 5, 1893), 82–84. Tanner's illustration for this article was first discovered by Eileen Southern and Josephine Wright, Iconography of Music in African-American Culture (1770s–1920s) (New York: Garland, 2000), ill. on 213. The authors did not connect the image to the text of Stuart's story.

[35] Tanner's photo is reproduced as fig. 23 in Mosby and Sewell, Tanner, 116. This photo descended in Tanner's family.

[36] Stuart, "Uncle Tim," 82.

[37] Ibid., 83.

[38] Statement in Tanner's hand in the files of the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf, Philadelphia. Quoted in Mosby and Sewell, Tanner, 116.

[39] See also E. P. Noble, "The Chicago Conference on Africa," Our Day 12, no. 70 (October 1893), 299 (printed incorrectly as 1983 in Sewell and Mosby, Tanner, 293n33), for evidence of Tanner's optimistic view of the future of African American art: "Professor Tanner . . . spoke of Negro painters and sculptors, and claimed that actual achievement proves Negroes to possess ability and talent for successful competition with white artists."

[40] See especially Boime, "Subversion of Genre," 442.

[41] Unaware of The Banjo Lesson's literary source, Jo-Ann Morgan writes: "The mystery of The Banjo Lesson persists." Uncle Tom's Cabin as Visual Culture (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2007), 202.

[42] Burns, "Whiteface," 82.

[43] Michael G. Harris, "From The Banjo Lesson to The Piano Lesson: Reclaiming the Song," in Mazow, Picturing the Banjo, 152.

[44] "The Banjo Lesson," cat. entry no. 27, in Mosby and Sewell, Tanner, 125.

[45] HOT, "The Story of an Artist's Life, II: Recognition," World's Work(July 1909): 11771.

[46] HOT to Frederick Douglass, May 7, 1894, Frederick Douglass Papers, Library of Congress. This important letter has not been cited in any previous studies on Tanner. On the issue whether or not The Banjo Lesson was in the Salon see, for example, Burns, "Whiteface," at 82: "Tanner's Banjo Lesson was exhibited at the Salon in Paris in May 1894. It may have been the painting now in the Hampton Institute, but the artist also produced another version now known only through the wood engraving published in Harper's Young People in 1893."The present author contends that the illustration in Harper'sYoung People was not "after Tanner" as suggested in the Palmer catalogue (See Leo Mazow, "From Sonic to Social: Noise, Quiet, and Nineteenth-Century American Banjo Imagery," in Picturing the Banjo, at 103: "A print after a related Tanner painting, now lost, appeared in an article by Ruth M. Stuart for Harper's Young People in 1893 with the title Dis Heah's a Fus'-Class Thing ter Work Off Bad Tempers Wid."), but rather a photomechanical reproduction of a Tanner grisaille. The original illustration is lost to us because these illustrations, once paid for, became the property of the magazine and were seldom returned. Tanner never would have entered a mere copy of a black-and-white photograph—one made to be an illustration for a children's magazine—into the Salon. The Hampton Banjo Lesson was in the Salon of 1894. The confusion in the Palmer Museum catalogue stems from the fact the authors did not work from the Tanner illustration as it appeared in Harper's Young People, but rather after a cropped image of the illustration that appeared in Ruth McEnery Stuart's Solomon Crow's Christmas Pockets and Other Tales (1896; Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1969), frontispiece. In that cropped image, Tanner's monogram signature and the date of the illustration, 1893, are missing, though they are clearly visible in Harper'sYoung People (see fig. 8). In Leo Mazow, "From Sonic to Social: Noise, Quiet, and Nineteenth-Century American Banjo Imagery," in Picturing the Banjo, 103, the cropped Tanner illustration is reproduced, cited as "after Tanner" and dated "circa 1893."

[47] HOT, "An Artist's Autobiography," Standard March 22, 1913, 866.

[48] See Mosby, "Reflections on Race," and for a specific discussion of Tanner's complex relationship with race, social pressure, and patronage, see Boime, "Subversion of Genre."

[49] Mosby and Sewell, Tanner, 93.

[50] Ethelyn Friend, "A Success of the 97 Salon: H. O. Tanner's Fine Picture, the 'Raising of Lazarus,'" New YorkHerald, June 18, 1897, Tanner Papers, roll D396, frames 1618–19. Friend's contemporaneous assessment that Tanner had only a "hint" of African descent is dramatically underscored in Marcus Bruce, Henry Ossawa Tanner: A Spiritual Biography (New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, 2002). In this recent book, a biographical study of the artist, a black-and-white photographic portrait is reproduced on page 95 along with the caption, "Henry Ossawa Tanner, early 1920s." This photograph is not of Tanner but of Tanner's white friend Atherton Curtis. This mistake underscores how, even today, in a study specifically on Tanner, his African American status can be missed.

[51] Friend, "Success," Tanner Papers, roll D396, frames 1618–19.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Tanner Papers, roll D306, frame 0019.

[54] Interracial marriage was not illegal in London. According to Lucy Bland, "White Women and Men of Colour: Miscegenation Fears in Britain after the Great War," Gender & History 17, no. 1 (April 2005): 29–61, at 31. "Hostility towards interracial relationships in Britain has never taken legislative form, but this was not true of some of its colonies . . . European women were being encouraged to migrate to the colonies, and their presence and protection were repeatedly invoked to clarify racial lines."

[55] Indeed, articles on Tanner in America began to proliferate not long after he married Jessie: E. F. Baldwin's "A Negro Artist of Unique Power" appeared in the Outlook in 1900, while Helen Cole's, "Henry O. Tanner, Painter," appeared in Brush and Pencil in that same year. Tanner continued to exhibit at the Paris Salon in the early part of the new century, as well as in Philadelphia, New York, Pittsburgh, Chicago, St. Louis, and even in the American West in Portland and eventually Los Angeles.

[56] A fascinating correspondence exists between Tanner's language in his 1914 letter to Tjietens and that in James Weldon Johnson's The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, published anonymously in 1912 (New York: Sherman, French and Company), two years before Tanner's draft. The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man is a fictional story of a black man who chooses to pass for white. In the final paragraph of the novel, the "ex-colored man" (who narrates the story) regrets the choice he has made but nonetheless declares: "My love for my children makes me glad that I am what I am [italics added], and keeps me from desiring to be otherwise; and yet, when I sometimes open a little box in which I still keep my fast yellowing manuscripts, the only tangible remnants of a vanished dream, a dead ambition, a sacrificed talent, I cannot repress the thought, that, after all, I have chosen the lesser part, that I have sold my birthright for a mess of pottage." Also at the end of Johnson's novel the narrator says of his children, "there is nothing I would not suffer to keep the 'brand' from being placed upon them." Compare this with Tanner's contention regarding his own son. The narrator also writes, in the penultimate paragraph, of the great black social activists of his, and thus of Tanner's, time: "Even those who oppose them know that these men have the eternal principles of right on their side, and they will be victors even though they should go down in defeat. Beside them I feel small and selfish. I am an ordinarily successful white man who has made a lot of money. They are men who are making history and a race. I, too, might have taken part in a work so glorious." It is not known that Tanner read this novel, but significant parallels may be drawn between the "ex-colored man" and Tanner's own life. Like the "ex-colored man," Tanner was an artist (a painter as opposed to a musician, one who gave up African American themes as opposed to ragtime music, which the ex-colored man abandoned). Like the "ex-colored man," Tanner had married a white woman. And, Tanner's own father was one of the great black activists, and Tanner himself, had he remained in America, might have taken part in a "work so glorious." Finally, in 1925 Tanner donated twenty-five dollars to the NAACP and he received a thank-you note from James Weldon Johnson. Johnson's note is reprinted in Mathews, Tanner, 196–97.

[57] Guy Pène du Bois, Artists Say the Silliest Things (New York: American Artists Group, with Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1940), 110.

[58] Discrimination against African Americans existed in France among the French, as well, not just among expatriate Americans. For an overview, see William B. Cohen, The French Encounter with Africans (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003).

[59] John F. Hutchinson, Champions of Charity: War and the Rise of the Red Cross (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996), 268.

[60] Ibid., 270.

[61] Tanner Papers, roll D306, frame 0158. Letter dated November 26, 1917.

[62] Roger D. Launius, book review of Robert J. Rusnak, Walter Hines Page and The World's Work, 1900–1913 (Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1982), in Journal of Negro History 68, no. 1 (Winter 1983): 104–5.

[63] In the records of the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, Tanner is listed in the 'Directory of Paris Personnel/American Red Cross.' This directory, dated May 1918, is included in a file within "Reports and Lists" (file class 942.308), Red Cross Commission to France, 1917–34, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

[64] "We have recently authorized the enrollment of colored nurses and will take steps to select from lists which have already been submitted to us those who are eligible for enrollment." Jane A. Delano, director, Department of Nursing, American Red Cross, to the Division Director of the ARC, 10 June 1918, in Negro Personnel file folder, 300.1, Records of the American National Red Cross, 1917–34. This same letter describes how badges for colored personnel would be issued and their records kept in a separate "colored" file. Contrast this to information on the official American Red Cross website, where it is stated that Frances Elliott Davis was the first black nurse approved in 1917. See http://www.redcross.org/museum/exhibitis/aaexhibit_2.asp.

On the issue of black nurses being disallowed as late as October 1918, see the letter in this same file from Mary F. Waring, head of the National Association of Colored Women: "On October 10, Camp Sherman sent a call for nurses saying, 'Do not wait to write or telephone.' October 11, ONarriving applying to Miss. Leary, head Red Cross Nurse, this [colored] nurse was told she could not be used. This unpatriotic head nurse turned this trained nurse way while colored soldiers were falling in the ranks from influenza, dying in the hospitals from lack of nurses, and suffering unattended because of the epidemic which made the usual nursing force inadequate. Are colored nurses to be forever humiliated? Is there not some way by which we may know our status?"

[65] See Earnest L. Perry, Jr., "It's Time to Force a Change: The African-American Press' Campaign for a True Democracy," Central Michigan University, online at http://list.msu.edu/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind9910a&L=aejmc&T=O&P=5452 (accessed August 25, 2009). See also Foster Rhea Dulles, The American Red Cross: A History (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1950), 419: "The Red Cross originally ruled, in concurrence with both the Army and Navy, that only the blood of white persons would be accepted. . . . A new policy, again jointly agreed upon by the Red Cross and Army and Navy authorities, was thereupon adopted whereby Negro blood was accepted but processed separately from that of white persons."

[66] Mathews, Tanner, 176–77. The original jotting by Tanner is in Tanner Papers, roll D306, frame 1636.

[67] On Tanner's relationship to the Harlem Renaissance, Dewey Mosby writes: "It would be impossible to imagine the succeeding generation of African American artists who contributed to the Harlem Renaissance without the example of Tanner's single-minded pursuit of artistic success and his subsequent international recognition." See Mosby, "Henry Tanner," in Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, African American National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2008), 7: 486. However, philosopher Alain Locke in 1925 found Tanner distant from the Renaissance: "There have been notably successful Negro artists, but no development of a school of Negro art. Our Negro American painter of outstanding success is Henry O. Tanner. His career is a case in point. [He] has never maturely touched the portrayal of the Negro subject. Who can be certain what field the next Negro artists of note will command, or whether he will not be a landscapist or a master of still life or of purely decorative painting? But from the point of view of our artistic talent in bulk—it is a different matter. We ought to and must have a school of Negro art, a local and racially representative tradition. And that we have not, explains why the generation of Negro artists succeeding Mr. Tanner had only the inspiration of his greatness to fire their ambitions, but not the guidance of a distinctive tradition to focus and direct their talents." Alain Locke, ed., The New Negro (New York, 1925; reissued New York, 1968), 265–66.

[68] Jesse Ossawa Tanner, "Introduction," in Mathews, Tanner, xiii. "Though my father felt that the presence of God stretches out through the cosmos and his love extends to other worlds than our own, he also felt that man has an active role to play and should not submit passively to his fate."

[69] HOT, "An Artist's Autobiography," The Advance, March 20, 1913, 14.