The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

| Please note: selected figures are viewable by clicking on the figure numbers which are hyperlinked. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sarah Bernhardt: The Art of High Drama |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

According to the myth inseparable from her name, she slept in a coffin and kept a menagerie of wild animals in her home. Twice married and the mother of a son out of wedlock (perhaps fathered by a Belgian prince), her lovers, male and female, were said to include Victor Hugo, the well-known classical actor Mounet-Sully, and the artists Alfred Stevens, and Louise Abbéma. She toured America nine times, traveling in her personalized train, and played there to packed houses and wildly enthusiastic crowds, as she did in Cairo, Istanbul, Tahiti, Rio de Janeiro, and throughout Europe. Following the amputation of her leg in 1915, at age seventy-one she voyaged to the war front to perform patriotic pieces for French soldiers, arriving in a sedan chair. On her death in 1923, throngs of Parisians came out for her funeral procession, which passed in front of the theater named for her, site of some of her most memorable performances in roles both male and female as well. Born in 1844 to a Jewish courtesan, she became the most celebrated actress of her day, in an era of immense popularity for the theater. At the same time, she became a living legend, her larger than life status rendered by Georges Clairin in his eight-foot high portrait showing her sensual serpentine body draped across a divan, a vision in white satin and feathers. "Was she magnificent?" a wide-eyed Marilyn Monroe asks about her in The Seven-Year Itch, in a clip projected on a screen at the entrance to Sarah Bernhardt: The Art of High Drama, at The Jewish Museum in New York. The response provided by this groundbreaking exhibit, the first major museum show of its kind devoted to Sarah, and by its equally superb catalog, co-curated and co-edited by Carol Ockman and Kenneth E. Silver, is a resounding 'Yes!' | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abbott Miller and Michelle Reeb's stunning installation for the show echoes one of its two main themes: Sarah Bernhardt as the inventor of modern stardom. The deep incandescent blue of the walls, intensified by stage lighting that creates pockets of dramatic illumination and dark shadow (with no ill effect to the viewing of the approximately 250 items on display), evoke both Sarah's renown as a stage performer and a 'stardust memories' quality reminiscent of old Hollywood (figs. 1 and 2). The vaporous blue also serves as an effective foil for both the warm wood found in artifacts such as Sarah's ornate standing mirror (fig. 3) and the rich, patinated colors of other objects in the show.1 The appearance at the entrance to the show, in oversized capital letters glowing with a neon effect, of a rebuke traditionally addressed to histrionic young women—"Who do you think are, Sarah Bernhardt?" (fig. 4) —can be reread upon exiting the show in a more literal fashion: aspiring stars the world over do indeed think they are Sarah Bernhardt. As Carol Ockman asserts in her catalog essay, "Was She Magnificent? Sarah Bernhardt's Reach," Bernhardt "established the template for show business icons as we know them" (71). Numerous display cases enclose single items and are set apart either on pedestals or against a large space of blue wall, lit up by incandescent bulbs positioned as footlights (fig. 5). This singling out of selected artifacts—the skull given to Sarah by Victor Hugo inscribed with a verse from Hernani; her ermine capelet with high collar (fig. 6); her handkerchief, handed down like a talisman through the generations from a celebrated older female actress to a younger one on the occasion of a great performance by the latter (fig. 7)—reinforces their iconic status in their association with this first modern diva. In other display cases, by contrast, groups of artifacts are clustered together in a style reminiscent of the fin-de-siècle esthetic of bric-a-brac that Sarah made her own (fig. 8). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

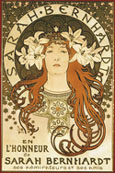

| Miller and Reeb's installation is thus a worthy set piece for this "most popular figure of her time," as Joan Rosenbaum, the Helen Goldsmith Menschel Director of the Jewish Museum, reminds us in her foreword to the catalog (ix). At the same time, the installation provides a setting in which the show's remarkable variety of rarely exhibited artifacts—costumes (fig. 9), jewelry (fig. 10), furniture, fine books, letters, ephemera— and media—painting, sculpture, film, sound recording, graphic and decorative arts—can both cohere and dialog. For example, Alphonse Mucha's series of Bernhardt posters confronts a series of the actress's film clips being projected across from them. The multi-media approach skillfully developed by the co-curators, which distinguishes this exhibit from all previous ones devoted to Bernhardt, is thus an entirely appropriate vehicle for both mirroring and interrogating Sarah's own innovations in this domain. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The star-worthy installation is one among many features of the exhibit that serve to perpetuate the Bernhardt legend; we are clearly in the realm of Sarah-worship here. At the same time, however, the exhibit succeeds in deconstructing the legend and probing how and why Sarah rose to become "the first modern star in the West" (xv). To provide the richly textured explanations for Sarah's stardom that are one of the hallmarks of this show and its catalog, art historians Ockman and Silver, and their collaborators, rely on an interdisciplinary approach encompassing social and cultural history, gender and queer studies, Jewish and cultural studies. This approach, in turn, makes possible a fascinating exploration of the second major theme of the show: Sarah Bernhardt as both unique and emblematic of her times, and especially of a peculiarly paradoxical modernity associated with the turn of the twentieth century. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How, then, did Sarah achieve stardom? First, by being one of the earliest artists to take advantage of the many new technologies of the late nineteenth century, and the new media they spawned, in order to create her image, and then to control it. She arrived on the scene at a fortuitous moment in the history of technology: the early nineteenth century development of photography, followed by its application to increasingly mechanized (and less costly) printing procedures, and then the introduction of color, all contributed to the so-called photomechanical and color "revolutions" of the last two decades of the nineteenth century. This era was also, simply, "the age of paper," or so proclaimed the title of an 1898 woodcut by Félix Vallotton in an allusion to the proliferation and influence of not only daily newspapers, but also books, posters, calendars, maps, postcards, playbills, sheet music, menus and myriad other forms of printed products.2 At the same time, accelerating literacy rates and enhanced purchasing power were among the factors engendering a public avid to consume such a flood of images. And both the liberation of the press and publishing in France in 1881, for the first time in a century, and the expanding rail and maritime networks of this period, facilitated the proliferation and circulation of these images not only in France, but internationally. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Photography first. The series of portraits of twenty-year-old Bernhardt by the pioneering Nadar, taken in 1860, figure her as a budding tragédienne at the time of her debut at the Comédie Française, swathed in sensual drapery and leaning against a column, the expression dignified and pensive (fig. 12 and fig. 13). Although her real dramatic success was still ten years in the future, these images seem to point ahead prophetically (albeit willfully on the part of both photographer and subject) to the emerging destiny of this star in the making (25-28). In tandem with improvements in photographic techniques, Bernhardt turned her "brilliant instincts about visuality and repetition," as Janis Bergman-Carton writes in her catalog essay (109), to the creation of a bank of photographic (and other) images of her. These included cabinet cards—the principle vehicle for commercial portraiture in the latter nineteenth century—showing Bernhardt costumed in faux-Byzantine splendor in her role as the Empress Théodora (fig. 14), for example, or stretched out in her infamous coffin (fig. 15). Other photographs displayed her equally idiosyncratic homes, overflowing with furs, fronds, and bibelots—emblems of her "extravagant esthetic" (13). The mass production of such photographic ephemera featuring Bernhardt clearly marked her as a celebrity; photo-portraits of this type began to circulate widely during this era, for example in the annual Albums Mariani series, published and financed beginning in 1894 by the creator of a popular coca-laced wine tonic and featuring images of a mini-Pantheon of France's contemporary glories from the fields of politics, journalism, the military, and the arts. Moreover, the photographs of Bernhardt's homes, most likely featured in the press, belonged to an emerging genre of photojournalism that allowed the public to glimpse the private lives of celebrities—a kind of "Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous" or "Cribs" avant la lettre. Such photographic 'visits' to celebrity homes paradoxically both elevated these individuals and at the same time—as culture became increasingly democratized in Third Republic France—superficially drew them nearer to their public. In Sarah's case, moreover, such visions of her opulent homes further blurred the distinction between the magnificence of both her life and her art. And like the four albums of nearly 200 photographs of himself compiled by Bernhardt's friend, the poet and archetypal dandy Count Robert de Montesquiou—and titled by him, simply, "Ego Imago"—the profusion of images produced under Sarah's direction were also meant to assure her immortality.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bernhardt relied not only on photography, but also on another new medium, color print advertising, for the circulation and commercialization of her image. The patenting of color lithography, and the introduction of four-color photomechanical printing, were both innovations of the nineteenth century. Their application to print advertising was in part both cause and consequence of the burgeoning mass consumer culture that was a mark of Haussmann's Paris and its successors. This materialism was evident in the opening of department stores such as Au Bon Marché, the vogue for collecting, and the taste for overstuffed decors à la Bernhardt. The artful combination of words and images in large scale color advertising had overrun Paris to such an extent, noted a bedazzled Italian visitor to the capital in 1878, a feature echoed in the colorful window displays and large gilt letters running along the balconies of the boulevards, that the city now needed to be 'read' like an illustrated book.4 Bernhardt understood that the seduction exercised by color advertising in its early stages, as well as the type of 'branding' with which it was associated, could function as a powerful instrument of her own seduction. Forecasting the placement of sports stars on Wheaties cereal boxes, her commodified image was reproduced on advertisements to sell desserts, tea, beef bouillon, biscuits, aperitifs (fig. 16), cars, and face powder. At the same time as Sarah sold the product, however, the product sold Sarah, as in a series of trading card advertisements-cum-souvenirs showing Sarah in scenes from L'Aiglon. Produced circa 1900, the same year as L'Aiglon, these images d'Epinal provided free advertising for Bernhardt's latest dramatic success. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sarah thus proved prescient in intuiting the "mechanisms of media-based celebrity" (24) especially in regard to new media such as advertising, sound recording (Edison recorded her voice, crackling yet imposing nevertheless), and also early cinema. The exhibit features clips from the films she performed in from 1908 until her death, many of them screen versions of her best-known plays such as La Tosca, thereby conflating her roles as both "the last great stage actress of the nineteenth century" and "the world's first movie star" (25). In adding her luster to these media, she helped legitimate the forms of popular culture denigrated by many of her contemporaries as the antithesis of art in their reliance on mass reproduction and integration into consumer culture. This was a doubly daring move for an actress who had originated in the distinctly high culture milieu of classical drama at the Comédie Française. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yet Sarah also understood that not all images were equal in quality, and that perhaps above all others "a designer of exceptional talent could advance her career" (13). She found this talent, for example, with the great poster artist Jules Chéret, who in an 1890 poster for "La Diaphane—Poudre de Riz Sarah Bernhardt" made Sarah into one of his trademark chérettes, a female figure whose tightly corseted, bright red torso and plunging neckline enhanced the association between carnal and consumer desire (an equivalence made more explicit by the fact that the face powder in question was known to be used by prostitutes). But most importantly, Bernhardt found this "designer of exceptional talent" in the Czech-born graphic artist Alphonse Mucha. Fifteen years younger than Bernhardt, Mucha was working in relative obscurity following his 1887 arrival in Paris until his 1894 poster of Sarah in Victorien Sardou's Gismonda set both artist and actress on the path to renown; Mucha as one of the foremost exponents of Art Nouveau design both in France and his native Czechoslovakia, and Sarah as the idol of boulevard theater. Their collaboration, however, marked an intersection of reverse trajectories: Sarah's from the world of high culture or 'art' as represented by the Comédie Française downward to the culturally devalued, yet immensely popular, world of boulevard theater; Mucha's in the opposite direction, from commercial graphic art to the legitimacy accompanying his later official commissions from the Czech government. During the six years Mucha was under exclusive contract with Bernhardt, he produced stage sets and costumes, such as the pearl-covered diadem she wore in La Princesse lointaine, co-designed by René Lalique (fig. 17), and seven posters for her plays, all on view in the exhibit. In displaying these seven-foot posters together in a row—elevated slightly above eye-level to further reinforce Bernhardt's larger-than-life stature in them (fig. 18)—the exhibit clarifies a crucial element of their collective composition: repetition. "Framed" by the name of the play at the top and that of the theater at the bottom, as well as by an elaborate decorative alcove, the full-length figure of Bernhardt occupies the greatest vertical length of each poster, with each of her characters holding an identifying prop, a book in the case of Lorenzaccio, a dagger in Medea's (fig. 19). While each poster is unique—with their abundant abstract patterns drawing on floral and other organic forms, arabesque lines, and soft colors making them some of the finest expressions of fin-de-siècle graphic design (fig. 20 and fig. 21)—together they rely on the same aesthetic of duplication so vital to Bernhardt's success. This 'reproductive' model, Ockman argues, was also conveyed in the repetitive form and plot line of the eight melodramas written for Sarah by Victorien Sardou (56), which to some critics conjured up the 'assembly line' quality disparagingly associated with American industrialism. The exhibit thus makes clear how the partnership between highly media-savvy performers and artists associated with popular culture—for example, between a vampish Madonna and David Fincher, director of the 1990 video, "Vogue", (itself a tribute to Hollywood icons such as Marlene Dietrich and Bette Davis)—can become a crucial vector of stardom. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Of course, Bernhardt was not the only performer to help invent herself as a monstre sacré during her time.5 Her contemporaries Enrico Caruso, Harry Houdini and Nellie Melba enjoyed the same type of public adulation that bore tribute to their celebrity—and their egos; this hyperbolic praise was conveyed in testimonies by Oscar Wilde, Mark Twain, Dumas fils, and others included in Karen Levitov's instructive and interesting essay, "The Divine Sarah and the Infernal Sally: Bernhardt in the Words of her Contemporaries." Moreover, the fin de siècle offers other examples of graphic artists creating what have become definitive images of popular entertainers, thus sending them up as stars in the emerging culture industry; Toulouse-Lautrec's posters of Jane Avril, Yvette Guilbert and Aristide Bruant, and Jules Chéret's images of Loie Fuller come to mind. Yet what separated Bernhardt from these entertainers, as Carol Ockman convincingly argues, was her 'reach.' Spanning widely disparate media, publics, countries, eras, and even conceptions of culture, nation and gender, her influence exceeded that of all others. It even extended into the late twentieth century, as suggested in Andy Warhol's silkscreen print of Sarah, from his 1980 series, Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century. To some extent reminiscent of other of Warhol's oversize head shots of female celebrities, such as Jackie O. and Marilyn, this portrait of Sarah also plays with tensions central to her image; between, for example, the real Sarah based on Napoleon Sarony's photograph and her abstracted image, and between her past and the afterglow of her image in the present. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bernhardt's commissioning of Mucha belonged to her broader entrepreneurship, a third component of her fame. While remembered primarily as an actress, Sarah was also a theater owner, producer, manager and director, with interests in several Parisian theaters including the eponymous Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt. Exercising complete creative and financial control over her productions, and starring in them as well, Sarah was an anomaly for her times, something more than a brilliant impresario on a par with her contemporary Sergei Diaghilev; as Ockman notes, she was indeed a "one woman dramatic enterprise" (56). While such an incursion into the traditionally male world of business ownership might surprise, the theater was one business where actress-owners could operate in relative freedom, due to the pariah-like status historically accorded to them. Authors and actresses such as Colette and Gabrielle Réju, albeit to a much lesser degree than Bernhardt, were intimately involved in the business of theater.6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

To the extent that this exhibit is about biography, it resonates with other recent efforts by biographers of well-known nineteenth century French women to explore how these women constructed their own identities, often in opposition to the familial and gender identities imposed on them. According to the historian Jo Burr Margadant, the 'new biography' thus no longer focuses "on the coherent self but rather a self that is performed to create an impression of coherence or an individual with multiple selves…"7 The 'performative' nature of female identity construction that has drawn the attention of some historians of nineteenth century France seems even more marked in the case of those women who were, in fact, performers: the actress turned journalist Marguerite Durand, for one, and of course Durand's friend Sarah herself. 'Performativity' emerges from the exhibit as a final component of Sarah's celebrity; her status as a star seemed to depend on her 'dying nightly' in a different way each time, sometimes in her famous 'death spiral' from La Dame aux Camélias. (Paired with Melandri's 1880 photo of Sarah ensconced in her coffin, these images also evoke what Ockman terms "the cult of invalidism" that was a staple of the fin-de-siècle iconography of women [52].) Her nightly death scenes typified both her famously physical style of acting in her thousands of performances (fig. 22) and, more generally, the theatrics that the public associated with her, and expected from her, both onstage and off as integral to her persona. Her costumes, such as her resplendent cape for Théodora (fig. 23), were flamboyant. Likewise, her two-story atelier near Paris's elegant Parc Monceau brimmed with the lush palms, patterned carpets, fringed throws, and Asian bibelots commensurate with her status as a member of theater's royalty, and as an artist in her own right, by virtue of her activities as a sculptor; her studio is depicted in an 1899 painting by Walford Graham Robertson, within which Clarin's own portrait of Sarah also appears (fig. 24). Her ascension in a hot air balloon over the 1878 Paris World's Fair, her arrival in the 'new world' aboard her private train, 'Le Sarah Bernhardt,' and her equally dramatic departure from it on her 'farewell tour;' her posing with her acting troupe in full rain gear at Niagara Falls (as contemporary photographs reveal) were publicity stunts geared to generate buzz about 'la divine Sarah.' Everything in Sarah's life, this exhibit suggests, was a performance, in which the boundaries between art and life, actress and persona, real and invented blurred. Even the title of Sarah's 1907 memoir, Ma Double Vie (My Double Life)—covering only half her life and "scripted to present the star in a flattering light" (24) affirm that the types of paradoxes conveyed by the metaphor of acting were essential to her success. The theater was the original stage on which the "high drama" at the core of this exhibit could play out, whether in the form of the 'transgressions' represented by her male roles or in the scandals of her private life. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| If, as Carol Ockman asserts, "stardom as we know it today cannot be understood without [Bernhardt's] example" (70), neither, in a sense, can modernity. Bernhardt was, in Joan Rosenbaum's phrase, an "extraordinary figure of modernity" (ix), encapsulating and exploiting all the transformations and paradoxes of a turn of the century that, Janus-like, looked toward both past and future. Henry James called her "a child of her age—of her moment—and she has known how to profit by the idiosyncrasies of her time" (126). One of these idiosyncrasies centered on the opposition between Sarah's Catholic and Jewish identities and, more broadly, between her 'Frenchness' and her 'Jewishness.' In exploring how these important personal tensions resonated more broadly in fin-de-siècle culture, this exhibit forms part of a rich, sustained reflection on this theme, at the forefront of three previous exhibits at the Jewish Museum: The Dreyfus Affair: Art, Truth and Justice (1987), The Emergence of Jewish Artists in Nineteenth-Century Europe (2001), and The Power of Conversation: Jewish Women and their Salons, which focused in part on Jewish salonnières of the 1890s (2005). A crucial moment in the post-Emancipation history of European Jewry, the final decades of the nineteenth century witnessed both the opportunities afforded by assimilation, urbanization and secularization—in France, Jews rose to the highest levels of success in the liberal professions, administration, and academia, for example—and simultaneously, the challenges posed by the eruption of nationalism, and its corollary, anti-Semitism. This period was marked as well by the emergence of Jewish nationalism in the form of organized Zionism. How did Sarah Bernhardt, Jewish by her mother, yet raised Catholic, respond to these challenges? How did her reaction compare to those of her contemporaries? In part, Ockman and Silver argue, Bernhardt's answer involved exploiting her "equivocal religious identity" (2) in roles like Photine in La Samaritaine (1897), a beautiful Jewess who converts to Christianity and is redeemed. Featuring an exoticized Sarah, Hebrew words and 'Semiticized' lettering, Mucha's poster for the play, performed in 1897, the year of the first Zionist Congress and nearing the height of the Dreyfus Affair, perhaps suggested to Sarah's public that the same 'redemption' might await her as well (fig. 25). Resolving and transcending the contradictions in her life by metamorphosing them into characters such as Photine, the co-curators rightly argue in their introduction, Sarah Bernhardt originated a powerful myth about herself. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| While Bernhardt could perform her Jewish identity to her advantage, however, she could exert much less control over the anti-Semitic images of which she was the subject, as had been her forerunner, the great classical actress of July Monarchy France, Rachel. The 'racial' concept of Jewishness, elaborated in the anti-Semitic blockbuster of the fin de siècle, Edouard Drumont's La France juive (1886), and disseminated in an entire literature on the subject during the era referred to by the historian Pierre Birnbaum as "the anti-Semitic moment,"8 worked its way into caricatures such as the one by Alfred Le Petit, showing a frizzy-haired, hook-nosed, vermin-like Sarah absconding at the end of the theater season with sacks of gold (fig. 26). Such attempts to 'out' Jewish-born converts, such as Arthur Meyer, director of the royalist and aristocratic Parisian daily, Le Gaulois, were not uncommon in an era in which "Jewish" and "French" were often considered antithetical. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Yet Bernhardt, the former convent school student, managed to transcend not only the perceived Jewish/Catholic divide but also the Jewish/French one by choosing to incarnate a hall of fame of French national heroes and heroines. In so doing, she achieved the remarkable feat of coming to be recognized as the greatest Frenchwoman of her time—even the embodiment of France—both at home and abroad. This is the thesis of the fascinating essay by Kenneth E. Silver, "Sarah Bernhardt and the Theatrics of French Nationalism: From Roland's Daughter to Napoleon's Son," which is quite original in its analysis of Bernhardt's importance concerning the dominant political debates of her day. Bernhardt's decision to be cast, or to cast herself, as Joan of Arc, Roland's daughter Berthe, the Revolutionary heroine Théroigne de Méricourt, and Napoleon's son, the duke of Reichstadt, is significant for several reasons. First, it conveyed her recognition that her "superimpositions of legendary performer and legendary character" (91) might burnish the reputations of both in a riot of Sarah/hero worship. Second, these roles were inscribed in a vein of cultural production for the theater whose aim was to boost French morale and whip up revanchisme following the disastrous 1870 defeat of France by Prussia, in part by revisiting past moments of French glory. Thus, Sarah's tapping into the Roland legend in Henri de Bornier's La Fille de Roland (1875), a story replete with crusading knights repelling the infidel Saracens, propelled audiences back to the heroic 'origins' of French history (during an era in which the textbook by French historian Ernest Lavisse was doing the same, albeit informing French schoolchildren that their 'ancestors' were not the Franks but the earlier Gauls). Similarly, Edmond Rostand's L'Aiglon, a play written expressly for Sarah, although the role was later evoked by Maude Adams, Eva Le Gallienne, and Judy Garland, reminded largely bourgeois audiences accustomed to seeing their social and political concerns transported to the stage that a temporary fall from Promethean heights (the Napoleonic Empire; the pre-1870 Second Empire of Napoleon III) could be righted through patriotic fervor intense enough to vanquish a hereditary enemy (Austria; Prussia). Playing the seventeen-year-old l'aiglon ('eaglet'), fifty-five-year-old Sarah was surely the only actress who could channel the quest for immortality—and the megalomania—associated with the Napoleonic legend (fig. 27). She was also the only one, as Silver interestingly suggests, who could bridge France's republican and Bonapartist traditions, both onstage and in her own position as a "centrist republican with leftist leanings and a predilection for Bonapartism" (79), in order to help forge a national consensus. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Such a consensus was lacking in France when L'Aiglon debuted in 1900, in the midst of the Dreyfus Affair. Like Edmond Rostand, author of the equally popular nationalist vehicle, Cyrano de Bergerac (1897), Sarah was a Dreyfusard, her allegiance movingly expressed in a letter to Dreyfus's champion, Emile Zola (fig. 28). Unlike Rostand, Sarah was Jewish by birth. One wonders whether her recreation of identifiably 'French' heroines was in part a means of asserting her own 'Frenchness' at a time when it was being challenged by many in the anti-Dreyfusard camp (including Bernhardt's own son, Maurice). Faced with the explosion of anti-Semitism erupting from the far right and far left during the Affair, French Jews responded in a great variety of ways; this task may have been especially complicated, Silver suggests, in the case of half-Jews such as Bernhardt and her contemporaries, Marcel Proust (and his narrator Marcel), the composer Reynaldo Hahn, and others. Some French Jews urged caution during the Affair, so as not to invite further attacks. Others, conversely, such as the anarchist intellectual Bernard Lazare, expressed their Jewish identity with increased militancy, with Lazare becoming a 'convert' to Zionism. Sarah's roles suggest that one of her responses to the Affair was to passionately reiterate her 'Frenchness,' much as did the patriotic Alsatian-born soldier, Alfred Dreyfus, while his military decorations were being ripped off him and flung to the ground in the courtyard of the Ecole Militaire. While Sarah's performance of French history, then, was a multiple signifier, no one could doubt the sincere patriotism of the woman who set up a military hospital for wounded soldiers during the 1870-71 siege of Paris, who visited the front during World War I, and who was acknowledged for these efforts by being named to the Légion d'honneur. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A half-Jew playing a Christian, a middle-aged adult playing a teenager, what of a woman playing a man? Bernhardt, of course, was famous for this, starring not only as the male lead in L'Aiglon, but also in Alfred de Musset's Lorenzaccio (1896), Hamlet (1899) (fig. 29), and Pelléas and Mélisande (1905) (fig. 30). She chose these roles in part because she felt that women's greater maturity led to a more nuanced understanding, and thus a superior performance, of male characters. Her notorious gender-bending reinforced the other paradoxes essential to her persona, and resonate widely with the gender anxiety of the fin de siècle. As Karen Levitov argues, reactions to Sarah were "based largely on nineteenth-century concepts of gender and ethnicity" (127). To some, then, she was simply the 'divine Sarah,' the incarnation of the eternal feminine as rendered in Alfred Stevens's delicate portrait of her (fig. 31) or in a cabinet card showing her costumed for her role in Froufrou (fig. 32), her emblem seemingly the ladylike arabesque of both her 'death spiral' and Mucha's posters. To others, in this era when women were making important professional and legal gains, she was the femme nouvelle, a working woman by virtue of her activities as an actress, entrepreneur, and sculptor who exhibited her work at the official Salon; this last feature of her career, which has received scant attention in many accounts of her life, is thankfully on view here in a selection of Bernhardt's own work. To others still, she was the femme fatale, a 'monster' whose roles onstage and off constituted a veritable catalog of presumed female perversions (which for some observers were Jewish ones as well…): prostitution (La Dame aux Camélias), murder and suicide (Médée, Macbeth), vampirism (Cléopâtre, fig. 33), androgyny, promiscuity, lesbianism (her relationship with Louise Abbéma, fig. 34). Was she an "homme…manqué," to use the phrase of the Decadent author Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly, an amazone like her contemporaries the female authors Rachilde, "homme de lettres" and Gyp?9 Divine or infernal? To further exacerbate these tensions, she was photographed sculpting—traditionally a male profession—wearing a white satin pantsuit designed by none other than the couturier Charles Worth, known for his elegant creations for women of high society. As usual, Carol Ockman writes, Bernhardt "embodied the contradictions of her age and made them exciting" (25). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A final contradiction explored in the show, and more fully in Janis Bergman-Carton's essay, is that between art and decoration. Taking as her point of departure Bernhardt's involvement with the decorative arts as a creator, patron, consumer and muse—a unique topic that has received little if any systematic treatment—Bergman-Carton shows that this discussion concerns, once again, a number of important dialectics evoked throughout the show. One of these is that between 'high' and 'low' culture, a major theme of the exhibit. Both Sarah and fin-de-siècle decorative arts, Bergman-Carton writes, "claim early associations with elite institutions that are subsequently complicated by ties to reproductive technologies and commodity culture" (101). Having begun her career at the august Comédie Française, as Ockman points out, the 'commodified' (yet no less popular) Bernhardt, in a "startling example of downward mobility" (67), later played on the boulevards, and then in ice skating rinks, circus tents, and vaudeville halls. Similarly, the aristocratic Rococo esthetic at the origins of Art Nouveau later became compromised by the commercial production of bibelots in this style destined for a materialist bourgeois clientele. This argument is stimulating, yet the parallel made between the trajectory of a person and that of an artistic movement may give pause. Moreover, the point might be made more forcefully that, although "complicated by ties to reproductive technologies and commodity culture," both Sarah's performances and fin-de-siècle decorative arts were quickly re-legitimated. In the former case, this revalorization occurred through Sarah's own genius as actress and self-publicist, in the latter in part through the development of networks of collectors—initially devalued posters became 'collectibles' through series such as Les Maîtres de l'Affiche (1895-1900), for example—and official state patronage. Clearly, however, in all domains, the established hierarchies of 'fine' and 'applied' arts were being challenged and breaking down. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Art and decoration also echoed the opposition between masculine and feminine. Sarah's feminine image was reinforced during this era by her association with the decorative arts. In the rhetoric used by government officials and others to promote Art Nouveau (and at the same time constrict women's sphere of influence), women were seen as 'queens' of the type of ornately decorated interior decors Sarah's homes boasted.10 Moreover, bibelots and other types of decorative objects that Sarah commissioned and collected, such as serving pieces by Christofle and Henin engraved with Sarah's trademark motto, "Quand même" ("Against all odds," "Through it all") (fig. 35, see also fig. 28), were often spoken of as 'female,' in part as objects of consumption and desire.11 Of course, Sarah decorated herself as well. Following Oscar Wilde's injunction to either be a work of art or to wear one, Sarah flaunted velvet dresses, ornately embroidered kid gloves (fig. 36), and jewels by Lalique, in the process moving from the realm of the ornamental to become, herself, a "work of art" (99). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sarah Bernhardt: The Art of High Drama sets a new standard for interpreting Sarah Bernhardt and her times. The exhibit and catalog succeed in presenting the legendary Bernhardt in highly original ways, not just as a star, but as the maker of modern stardom; not just as the interpreter of French national heroes, but as France (or a certain idea of it) as well. At the same time, both the exhibit and catalog provide perceptive analyses of the turn-of-the-twentieth-century as a period of ferment, in which racial and gender anxiety, urbanization, and the intensification of both consumerism and leisure culture in conjunction with technological advances all contributed to the environment that made Bernhardt's success possible. In the end, Sarah emerges as a hybrid akin to the bronze inkwell she created depicting herself as the mysterious sphinx. But she also evokes the puzzle that shows her in her various roles that together form a portrait of Sarah as L'Aiglon (fig. 37). Sarah, too, remains a bit of a puzzle, made up of constantly scrambled pieces: actress, woman, Jew, French citizen, sculptor, icon. Was her life really as extraordinary as it seemed? Was she indeed an actress of unsurpassed talent, or simply talented as portraying herself this way? Was she magnificent? No doubt. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Willa Z. Silverman |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The author gratefully acknowledges for their assistance and guidance: Elizabeth Emery, Abbott Miller (Pentagram Design), Karen Levitov and Anne Scher (The Jewish Museum), Gabriel P. Weisberg, and Janet Whitmore. 1. E-mail correspondence with Abbott Miller, 1 Aug. 2006. 2. See Phillip Dennis Cate and Sinclair H. Hitchings, The Color Revolution: Color Lithography in France, 1890-1900 (Santa Barbara: Peregrine Smith, 1978). Félix Vallotton, "L'Age du Papier," Le Cri de Paris 23 Jan. 1898. This woodcut, whose title alludes to the power of the press during this period to mold public opinion, appeared shortly after the publication of Emile Zola's "J'Accuse…!" in L'Aurore. 3. See Philippe Thiébaut, Robert de Montesquiou ou l'art de paraître (Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1999), passim. Some of the photographs of Montesquiou contained in "Ego Imago" were taken by Nadar. 4. See Edmondo de Amicis, "Le Premier Jour à Paris," Souvenirs de Paris et de Londres (Paris: Hachette, 1880) 1-32. 5. On Bernhardt, Caruso, Melba and other monstres sacrés, see Jean-Michel Nectoux, Stars et monstres sacrés (Paris: Editions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1987). 6. See Mary Louise Roberts, "Acting Up: The Feminist Theatrics of Marguerite Durand," in Jo Burr Margadant, ed., The New Biography: Performing Femininity in Nineteenth-Century France (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000) 197 and passim. Roberts's discussion of the theater as an "important site for gender subversion" is germane to the presentation of Bernhardt in this exhibit. See also Mary Louise Roberts, Disruptive Acts: The New Woman in Fin-de-Siècle France (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2002), ch. 6, "The Fantastic Sarah Bernhadt," 165-219. 7. Jo Burr Margadant, "Introduction," in Margadant, ed., The New Biography, 7 8. Pierre Birnbaum, The Antisemitic Moment: A Tour of France in 1898, trans. Jane Marie Todd (New York: Hill and Wang, 2003). 9. Barbey d'Aurevilly, Les Bas-Bleus (1878) (Geneva: Slatkine Reprints, 1968) x. Gyp was the pseudonym of the popular novelist Sibylle-Gabrielle Marie-Antoinette de Riquetti de Mirabeau, comtesse de Martel de Janville (1849-1932), who also referred to herself as a man. Gyp was the author of Napoléonette (1913), a novel about the Emperor's female godchild who dons male clothing in order to join the emperor on the front. 10. On this theme, see Debora Silverman, Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siècle France: Politics, Psychology, and Style (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989) 63-74 and passim. 11. On the gendering of fine books as bibelots at the fin de siècle, see Willa Z. Silverman, "The Enemies of Books? Women and the Bibliophilic Imagination in Fin-de-Siècle France," Contemporary French Civilization 30:1 (Winter 2005/Spring 2006): 47-74.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||