The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|

The Thadée Natanson Panels: A Vuillard Decoration for S. Bing's Maison de l'Art Nouveau1 |

|||

| One of the high points of the important Chicago and New York exhibition "Beyond the Easel: Decorative Painting by Bonnard, Vuillard, Denis, and Roussel, 1890–1930" was the inclusion in New York of Vuillard's series of five decorative panels known as "The Album," painted in 1895 for Thadée Natanson (figs. 1–5).2 These gorgeous oil paintings, deep-colored and richly textured interior scenes of varying formats, represent young bourgeois women engaged in simple domestic activities, sharing an album, quietly conversing, arranging flowers, sewing, and embroidering. The curator of the exhibition, Gloria Groom, is to be congratulated for successfully reuniting all five panels of this major Nabis decoration for the first time since their dispersal in 1908.3 Groom's achievement was something of a lost opportunity, however. In the two different installations of the Album decoration in Chicago and New York, the paintings were hung in a curiously haphazard manner with no apparent attempt made to group the panels in any coherent order. Three panels were arbitrarily placed on a single wall, obvious pendants were reversed, etc. Furthermore, this casual hanging was not the result of any neglect on the part of the curator. Rather, the random installation of the Album panels was entirely in keeping with a thesis originally presented in Groom's book-length study Édouard Vuillard, Painter-Decorator: Patrons and Projects, 1892–1912, and later reiterated in Beyond the Easel, the exhibition catalogue accompanying the show.4 In both of these publications, Groom contends that the Album panels were conceived from the beginning as a kind of innovative, portable decoration intended to be hung as seen fit by its modern, mobile owners in various rooms of their Paris apartment, packed up and carried on summer vacations, and eventually installed in future residences.5 Though very original, Groom's thesis is fundamentally at odds with everything known about both Vuillard's meticulous working methods and his highly refined decorative aesthetic. His journal entries and numerous preparatory sketches for the Jardins publics (1894), for example, confirm that from the very conception of a decoration Vuillard was actively concerned with every aspect of its installation—with the lighting, dimensions, and function of the designated room, and with the format, order, spacing, and formal progression of his panels within that room.6 In short, nothing was ever left to chance in a Vuillard decoration. Moreover, there is substantial visual evidence in the panels themselves that suggests they compose a closely interrelated and harmoniously unified, continuous frieze (with brief ellipses), clearly designed for a specific room of intimate scale and function. But above all, Groom fails to investigate seriously a well-known fact about the Album panels, namely that they were exhibited in S. Bing's "Art Nouveau" exhibition a few weeks after being completed. The exceptional nature of the Album cycle within the context of Vuillard's decorative oeuvre suggests a stronger connection with Bing's exhibition and purposes exists than Groom would have us believe; for the Album panels speak a much less idiosyncratic language than his preceding decorations and exceptionally experiment with the formal innovations of more mainstream contemporary movements in the decorative arts. Though Groom presents ample visual documentation to support her thesis, her proof turns out, as we shall see, to deal with subsequent, truly arbitrary installations of the Album panels rather than with the original one. The purpose of our paper is to demonstrate that the Album panels were originally designed to decorate a small model room in S. Bing's Maison de l'Art Nouveau, as part of a Nabis group commission. Logically following up a somewhat earlier collaboration with Bing, this new commission was to be a further, more important occasion for the Nabis to develop a group aesthetic and to attempt once again to regenerate the original spirit of their brotherhood. Perhaps most significantly, however, the new commission was to be a first opportunity for Vuillard and the Nabis to demonstrate to an exhibition audience their ability to complement and enhance architecturally defined spaces and to show what the function of decoration in relation to architecture should be.7 | ||||

| The only reference in Vuillard's journal to the present decoration occurs in a summary the artist wrote in 1896 outlining the major events of the previous year. The entry reads simply "November, Panels for Thadée."8 Along with his brother, Alexandre, for whom Vuillard had painted the nine-panel cycle Les jardins publics during the summer of 1894, Thadée Natanson was one of the founders of La revue blanche. In his capacity as the magazine's principal art critic, Thadée was to be an important and increasingly enthusiastic champion of Vuillard's art; moreover, he was married to Misia Godebski, the beguiling and ebullient, impulsive and kittenish muse to at least two generations of painters, poets, composers, and playwrights. From the mid-1890s to the end of the decade, Vuillard's intimacy with the Natansons grew to the point that he saw them almost daily, either in their rue Saint-Florentin apartment or during his long sojourns at their country houses in Valvins, on the Seine near Fontainebleau, and Villeneuve-sur-Yonne, in Burgundy. | ||||

|

The panels mentioned by Vuillard in his journal are without a doubt the present five paintings, which were sold by Thadée Natanson at auction in 1908, several years after his divorce from Misia. In the catalogue written by Félix Fénéon to accompany the sale, the five paintings were entitled and described in terms of a decorative ensemble. For Fénéon the unity of the series is most readily perceived through Vuillard's continuous development of an exquisite, overall chromatic harmony. Since Vuillard's suggestively imprecise, densely textured paintings are at times hard to read and his sumptuous accords of color difficult to reproduce accurately in color reproduction, it seems worth reprinting Fénéon's catalogue descriptions here:

Though Vuillard's journal provides no further documentation concerning either the circumstances of the commission or the evolution of the project, paintings and photographs made by the artist between 1896 and 1899 of rooms in the three Natanson residences tell us something about the subsequent installation of the decoration. L'album and La table de toilette are seen hanging on opposite walls of the ground floor sitting room at La Grangette in Valvins, in two paintings by Vuillard datable to the second half of 1896.14 Then, beginning in 1897, after the Natansons had given up La Grangette, views by Vuillard of the Natanson's rue Saint-Florentin salon and dining room clearly show four of the five panels hanging on background walls: L'album can be seen over Misia's piano in Cipa écoutant Misia au piano (Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe) and Le salon des Natanson (Foundation E.G. Bührle Collection, Zürich); Le pot de grès and La tapisserie are hanging to the left and right of the dining room door in Le déjeuner, rue Saint-Florentin (Misia et Cipa) (private collection).15 A corner of Le corsage rayé appears in an unpublished photograph by Vuillard of Vallotton holding an infant by a window in the Natanson dining room (Archives Salomon, Paris). Finally, photographs Vuillard took about 1899 of the billiard room in Misia and Thadée's house at Villeneuve show that L'album and Le pot de grès had been moved there for a time.16 This evidence, which suggests a curiously tentative, haphazard installation of the panels, led Gloria Groom to conclude that Vuillard expressly designed for the Natansons a kind of portable decoration whose panels could be separated and arranged according to the owner's whim.17 This deduction contradicts not only Fénéon's catalogue entries but other period sources—including Thadée himself, for whom the panels constituted an harmonious ensemble, one that had, furthermore, been exhibited as such at S. Bing's Hôtel de l'Art Nouveau in December 1895.18 |

||||

|

In the course of 1895 the German-born, Paris-based dealer-entrepreneur Siegfried Bing, whose enthusiasm for the decorative arts had already resulted in a number of highly visible commercial ventures promoting the art of Japan, determined to transform his Paris townhouse on the corner of the rue Chauchat and the rue de Provence into a showcase for the "new art" (fig. 6).19 At the time of the opening of the Maison de l'Art Nouveau's inaugural exhibition in December 1895, Bing published a lithographed program stating his intentions:

Bing had not been content merely to unite under one roof the widest possible range of decorative arts in the new style; he had approached artists to design complete interiors for his gallery. The Nabis were called upon to participate: Maurice Denis created what was to be a much-criticized bedroom and Ranson painted panels for a dining room with wainscoting and furniture by Henry Van de Velde. Vuillard—and here all recent writers are in agreement—did not design new wall decorations, but instead sent the panels created for Thadée and Misia. The paintings were indeed listed in Bing's exhibition catalogue as a "decoration in five panels belonging to Madame Thadée Natanson,"21 but since they were painted in November 1895, which Vuillard states they were, then they could have been finished only a matter of weeks before the opening of Maison de l'Art Nouveau, at the end of December. Camille Mauclair, who had been one of the Nabis's strongest supporters and wrote numerous introductions for Le Barc de Boutteville catalogues,22 sheds light on this conjunction in a sharply critical review of Bing's first exhibition. Unhappy with the new direction in Vuillard's art, Mauclair implies that Bing's Art Nouveau played a significant role in this unfortunate development. In passing he provides important information on the origins of the "Thadée Natanson" decoration:

A more authoritative source, the architect Henry Van de Velde, states categorically that Bing offered a model room to Vuillard in June 1895, as soon as he had made the decision to create L'Art Nouveau:

Until now the exact location of the small salon in which Vuillard's panels were shown has not been established. According to Arsène Alexandre, Vuillard's "harmonious and discrete panels" were in a room contiguous to the great circular salon on the central floor with decorations by Albert Besnard.25 This precision is confirmed by Edmond Cousturier, who wrote a piece on Bing's model rooms for the Revue blanche in January 1896:

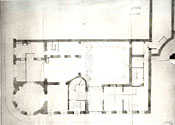

The antechamber or small salon in question can be seen in the plan of the central floor of the Maison de l'Art Nouveau (fig. 7) immediately to the right of the round salon.27 The room has five different surfaces, counting the narrow wall between the windows. Furthermore, the proportions of these walls correspond to those of the five Album panels permitting the following installation: the squarish Corsage rayé (fig. 1) on the wall opposite the windows, then moving clockwise, the longest panel, L'album (fig. 2) on the long wall, the vertical Tapisserie (fig. 3) between the windows, and the Table de toilette (fig. 4) and Le pot de grès (fig. 5)—long considered pendants on the basis of compositional features that interrelate these two panels more completely than any of the others—respectively to the left and right of the door leading into the Besnard salon. Even the slightly narrower width of the wall to the right of this door is reflected in the shorter length (by 3 centimeters) of Le pot de grès vis-à-vis its pendant. A drawing by Vuillard, which we discovered and identified in the Archives Salomon, corroborates this hypothetical arrangement and offers additional evidence that the panels must have been designed with Bing's model room in mind.28 The drawing represents five separate scenes, readily identifiable with the Album panels because of their unusual proportions.29 They appear in the same order as proposed above with the paired panels opposite the long horizontal panel. Here too, the last panel, which will become Le pot de grès, is slightly shorter in length than its pendant. Moreover, though only roughed out, the scenes in the drawing present views of women in gardens, not in interiors, implying that before he arrived at his definitive subjects, Vuillard was planning a decoration for the walls of Bing's antechamber.30 Vuillard must have first received the offer from Bing, referred to by Mauclair and Henry Van de Velde, and then found in Thadée Natanson a willing patron to back the project—Thadée would later write a spirited defense of Bing's enterprise in the Revue blanche—much as Maurice Denis succeeded in getting partial funding for his bedroom from Bing himself.31 In any event, the only true installation the Album panels ever seem to have had was in the Maison de l'Art Nouveau, where they remained on view for several months before being returned to the Natansons, to be hung in an arbitrary manner in their various residences.32 |

||||

|

|

||||

| Most writers on Vuillard are in agreement that the Album panels (figs. 1–5) are closely interrelated thematically, chromatically, and texturally through the all-pervasive, densely interwoven patterns of flowers, fabrics, and wallpaper. For the first time in his career, Vuillard openly evokes the art of tapestry in a multi-panel decoration. Furthermore, in the Album decoration Vuillard consciously alludes to his emulation of this analogous decorative aesthetic in a charming, witty conceit. The seated young woman seen "weaving" in Tapisserie (fig. 3) is not actually fabricating a true tapestry. Rather, she is embroidering a stretched canvas employing needles and dyed-wool yarns in a kind of imitation tapestry, much as Vuillard himself used brushes and oil paints to imitate woven tapestry on the stretched canvases of his Album panels. | ||||

| The Album panels are further unified by a harmonious play of light. Vuillard's little sitting room was said to be very dimly lighted, only by a curious chandelier.33 Firsthand accounts suggest that the large ground-floor windows to either side of Tapisserie, like windows in other model rooms of Bing's gallery, were blacked out or heavily curtained in order to lower the level of light, creating a hermetic environment into which the outside world could not intrude.34 With wonderful inventiveness Vuillard replaces these real windows with a painted, fictitious window in Tapisserie, and it is this sole, unreal window that Vuillard establishes as the true source of light for his entire decoration. When the Album panels are arranged in the order proposed above, all the scenes turn out to be consistently lighted by this painted window: Le corsage rayé (fig. 1), on the wall opposite the "window," is lighted from straight on; L'album (fig. 2), on the long wall to one side, is lighted from the right; and the two pendants, La table de toilette (fig. 4) and Le pot de grès (fig. 5), opposite L'album and to the other side of the "window," are both lighted from the left. But the true quality of Vuillard's magical invented light is comprehended more fully only when the viewer becomes aware of the girl in the rear of Tapisserie, who is drawing back the curtain on the window. Quite suddenly we realize that the light irradiating Vuillard's interior scenes is only just entering the "room" and that it is a simple everyday gesture—the drawing back of a curtain—that has had the effect of casting a spell on the room's inhabitants. It is this banal gesture that temporalizes Vuillard's decoration, transforming and uniting the seemingly timeless separate scenes of the Album panels, into a single, quintessential Vuillard moment that is at once intimate, poetic, and mysterious. | ||||

|

|

||||

|

Félix Fénéon was the first to recognize that the abstract linear arabesque played a fundamental role in the overall design of the Album panels. Again from his auction catalogue entries:

In a preface written for the same catalogue of Thadée Natanson's 1908 auction, Octave Mirbeau devoted a paragraph to Vuillard in which he especially praised the artist's wall decorations, alluding thereby to the presence of the Album panels in the sale. Like Fénéon in his formal analysis of L'album, Mirbeau emphasizes the abstract quality of Vuillard's art, but he goes beyond Fénéon in maintaining that these abstractions are imbued with a sumptuous sensuousness, and that they are the rhythmic inventions of a musical imagination:

The revisions in favor of greater unity carried out by Vuillard in somewhat earlier easel paintings such as La dame en bleu (1895, oil on cardboard; private collection) and Autoportrait: Vuillard décorateur (1894/95, oil on canvas; private collection) have been developed and adapted for mural decoration in the Album panels.37 The cycle forms a continuous horizontal frieze, 65 centimeters in height, with a single vertical accent, La tapisserie (fig. 3), whose dimensions were predetermined by the two windows flanking it on the outside wall of the room. Movement from left to right throughout the entire frieze is generated by a single flowing arabesque, which operates as a billowing undulation made by the placements of flowers, the leaning of the women's heads, and the positioning of their arms. Twice the course of the arabesque is interrupted by vertical retards: first by the figure standing at right in L'album, a contravention augmented by the vertical format of the immediately succeeding Tapisserie, in which, however, the shoulder, sleeve, and work cloth of the weaver make a patch of light pointing to the right and even the folds of the curtain yield to the dynamic; and then again, though less emphatically, by the figure seen from behind, standing at right in La table de toilette (fig. 4). Vuillard's frieze is predominantly planar; the scale of the two figures entering from an indeterminate remove barely registers as a slight inflection of this planarity. However, as the arabesque advances, the flat, fused composition gives way in two instances, midway through L'album, and again in La table de toilette, swelling magically into larger waves of atmospheric space. It is in these passages that Vuillard concentrates and orchestrates his pictorial variants: modeled features, strong clair-obscur, solid colors and verticals in the midst of a decoration dominated by planar faces, soft clair-obscur, ornamental motifs, and erratic sinuosities. Critics of Vuillard have frequently had to resort to musical comparisons, and these passages are like a sweeping modulation of tone.38 With the Album panels Vuillard achieves a breakthrough in his handling of pictorial contrasts, moderating still further the virtuoso counterpoint of his 1893 pictures and inaugurating new harmonic progressions, which, while as expansive as those introduced in the Jardins publics, now seem less idiosyncratic and, appropriately, more Art Nouveau. |

||||

|

In his critique of Vuillard's model room for Bing cited above, Camille Mauclair detected and lamented the new direction Vuillard's art had taken.39 His exhibition review intimates that Vuillard had allied himself with Bing's revival of the decorative arts in France and was now working under the banner of Art Nouveau. In the context of Mauclair's remarks, it is useful to recall Fénéon's assertion above that the arabesque is the essential abstract formal feature not only of Vuillard's Album panels, but of the best works by Vuillard's contemporaries as well.40 Looking at the other model rooms decorated by the Nabis for Bing, we discover that however dissimilar the rooms may seem initially they all employ the arabesque as an underlying unifying theme: Vuillard's sitting-room decoration, Denis's bedroom frieze The Love and Life of a Woman (Frauenliebe und Leben) and Ranson's dining-room murals depicting young peasant women working in fields all propose designs dominated by the sinuous rhythms of the linear arabesque.41 Bing's role in the Nabis' development of a broadly adaptable group aesthetic is confirmed in a letter written by Bing to Denis on 30 August 1895, some two months after the original commission:

The commission for the model rooms at l'Art Nouveau undoubtedly grew out of a successful Nabis group collaboration with Bing the previous year. In February 1894 Bing traveled to New York and Boston to organize important auctions and exhibitions of Oriental art. While in the United States, he took time to assess for himself the recent, much-acclaimed progress being made by the Americans in the realm of the decorative arts. Of all the studios and workshops Bing visited, that of the stained-glass maker Louis Comfort Tiffany impressed him the most, and before returning to Europe he discussed with Tiffany the possibility of having stained-glass windows made after designs by young French artists. Upon his return to France, Bing was in touch with the Nabis through one of their members, Henri Ibels, who in turn contacted Vuillard. In a letter written in late May 1894 Vuillard tells Maurice Denis of Bing's proposal:

On the basis of correspondence exchanged between Bing and Denis, Gabriel Weisberg, in Art Nouveau Bing, determined that most of the Nabis had completed their cartoons by the end of October 1894.44 Vuillard notes in a journal entry of 4 November that Bonnard, Roussel, and Ranson had all met with Bing concerning the stained-glass windows: "Monday morning Bonnard busy with Bing, Viau, Hoentschel . . . the afternoon . . . caught Bonnard who got paid this morning with Kerr and Ranson (the Ibel's business)."45 In the end Tiffany created thirteen stained-glass windows after designs by eleven French painters, eight of whom were Nabis: Maternité by Bonnard, Paysage by Maurice Denis, Été by Ibels, Moisson fleurie by Ranson, Le jardin by Roussel, three small windows by Sérusier, Parisiennes by Vallotton, and Marronniers by Vuillard—the three remaining artists were Albert Besnard, P. A. Isaac, and Toulouse-Lautrec.46 The windows were exhibited first at the Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts on the Champs-de-Mars, which opened on 25 April 1895, and then again at Bing's Salon de l'Art Nouveau at the end of the year.47 It has generally been agreed ever since that the Nabis achieved a remarkable degree of homogeneity in their Tiffany stained-glass designs through the bold compartmentalization of form and the shared application of a cloisonniste aesthetic. Along with the model rooms for Bing, which would mark a high point of Nabis involvement with Art Nouveau, the Tiffany windows are an important chapter in the history of the brotherhood. Both of Bing's commissions stimulated the Nabis to develop a group aesthetic in the broader context of a concerted effort to renew the original spirit of their brotherhood.48 |

||||

|

Claude Roger-Marx was the first writer on Vuillard to evoke the heightened Symbolist aura of the Album panels:

Roger-Marx's invocation of Maurice Denis in this context is especially appropriate, for the bedroom frieze conceived by Denis for Bing's Maison de l'Art Nouveau presents not only striking formal similarities with the Album panels, but also certain spiritual affinities. There is another artist, however, not cited by Roger-Marx, who is a spiritual and formal source for both Vuillard's and Denis's art—an artist who was later referred to by Denis as the very origin of plastic symbolism, "the Mallarmé of painting": Odilon Redon.50 In 1892 Albert Aurier had in effect predicted that the Nabis would fall under the spell of Redon's symbolism much as they already had the synthetism of Redon's younger contemporary Gauguin:

Born in 1840, Redon had produced more than half of his lithographic oeuvre before he was given his first retrospective, at the Galerie Durand-Ruel in the spring of 1894. The show was a revelation for the Nabis and it stimulated Thadée Natanson to write the first of a series of reviews in support of the artist he dubbed the "Prince of Dreams":

Later in 1897 Thadée published a piece on a new lithographic album by Redon, La maison hantée: "The whites powder, quiver; glimmers, vapors, flashes, reflections, shivers, variegated patterns, contribute to the magic of the blacks, and if they don't create them altogether, they complete their splendor, make the essence of their velvet glisten and make something miraculous of their absolute darkness."53 Then in 1899, on the occasion of a group exhibition at Durand-Ruel that was in effect an hommage à Redon by the younger generation, including Vuillard, Thadée wrote:

Vuillard owned a copy of Redon's lithographic album Les origines (1883), that he probably bought in 1893.55 The influence of these, as well as other of Redon's early tormented visions, on Vuillard's own lithography is most apparent in the lithographic programs Vuillard designed for the Symbolist Théâtre de l'Oeuvre in 1894. During that season Vuillard's evocations of scenes from plays by Ibsen, Hauptman, and Maurice Beaubourg become, with his growing mastery of the lithographic medium, utterly hallucinatory in their frightening intensity.56 Yet for a number of these same L'Oeuvre programs of 1894 Vuillard also designed more debonair lithographs advertising La revue blanche that were printed beside the dramatic scenes on the same sheet of paper, though they presumably appeared on the back when the programs were folded in two. These prints (figs. 8, 9), while presenting the same Redonesque obscurity, blurring, and sfumato effects as their pendants, have none of the nightmarish quality associated with the theater scenes. With their linear arabesques, their imprecision, and their gentle air of reverie they reflect instead the shift toward a more serene and lyrical imagery perceptible in Redon's lithography after 1890. More important, Vuillard's Revue blanche lithographs represent an unexpected adaptation of Redon's art, applying, as they do, a rarefied Symbolist aesthetic to the banal "observable and verifiable" motif of women in interiors, with flowers, reading—La revue blanche.57 Along with other of Vuillard's prints dating to 1894/95, these images are important, if small scale, charming antecedents of the Album panels, where Vuillard would draw more deeply on the art of Redon to generate an intensified Symbolist aura of mystery and reverie, and explore further the magical transforming potential of light and atmosphere.58 |

||||

|

Vuillard's decision to translate the imagery and effects of his black-and-white art into the muted colors and dense patterns of the present decoration may also have been prompted by Redon's example, possibly even with the encouragement of Thadée Natanson. It was only with the 1894 Durand-Ruel retrospective that Redon's admirers first became aware of the lithographer's recent experiments with oil and pastel and his new interest in color, which Gloria Groom has already suggested may have influenced the new color effects of the Album paintings.59 Again from Thadée's review of that exhibition:

Although Redon's well-known paintings and pastels of women in profile and flowers date to after 190061 and the incandescent colors associated with his works of the mid-1890s seem far removed from the muted coruscation of Vuillard's contemporary palette, Redon's sudden desire at the age of fifty-five to reinterpret his visionary art in terms of exquisite color relationships must have proved a major source of inspiration for the young Vuillard. |

||||

| In the context of meeting Bing's conditions for the creation of a harmonious ensemble of model rooms at the Maison de l'Art Nouveau, Vuillard has visualized an homage to an older artist who was finally gaining recognition—thanks in large part to Thadée Natanson—as the father of plastic symbolism. But the Album panels are also a moving testament to Vuillard's deep affection for Thadée Natanson, their aesthetic affinities, and their shared enthusiasm not only for the art of Redon but also for the whole range of literary symbolism. Therefore, while Vuillard painted the Album panels for a model sitting room at Art Nouveau (and thus not for Thadée Natanson's rue Saint-Florentin apartment), in another sense he did paint the decoration for Thadée. Thadée had been behind every one of Vuillard's decorative commissions thus far, he had frequently bought Vuillard's pictures, and he had even organized Vuillard's only one-man exhibition to date in the offices of the Revue Blanche.62 In his most generous gesture of all, one intended to introduce the decorative art of Vuillard to a public audience, Thadée paid for a decoration designed not for his own residence but for a room in a temporary exhibition gallery. At this juncture in his career, Vuillard probably had no other friend or patron who would have done the same. On the most personal level, then, Vuillard's decoration may well be an expression of his profound gratitude to the friend who had been his most fervent and faithful supporter. This sentiment is perhaps nowhere better summed up than in Vuillard's only surviving written reference to the decoration: "panels for Thadée." Finally, in more historical terms, the Album panels are an important chapter in late-nineteenth-century artistic patronage and an early example of a temporary exhibition mediating the relationship between the artist and the patron-art critic. | ||||

|

1. This article is a chapter from a book-length study entitled "Reconsidering Vuillard." Written originally to accompany the Vuillard catalogue raisonné, our texts are the product of five years of research in the Archives Salomon, Paris, as well as in French public libraries and archives. These years were also devoted to the completion of the Vuillard catalogue raisonné, most of which was assembled and organized by Annette Leduc Beaulieu. This version of the catalogue was accepted in 1993 for publication by two French publishers—Flammarion and Adam Biro. Collaboration with Adam Biro was at an advanced stage when in 1996 Antoine Salomon abruptly changed publishers. The new publisher, the Wildenstein Institute, rejected our texts and commentaries, and, as a consequence, our names were removed from the title page of the catalogue raisonné. A copy of our manuscript remains on deposit in the Archives Salomon, where, through a contractual agreement with Antoine Salomon, we retain exclusive rights to its use. 2. "Series of Five Decorative Panels known as 'Album,' 1895," in Groom 2001, pp. 126–31, nos. 35–39. Groom's exhibition and catalogue were the subject of a spirited and justifiably enthusiastic review in the first issue of Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide; see Roos 2002, unpag. 3. Natanson sale 1908, nos. 51–55. The five Album panels were reunited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the exhibition's second venue, from 26 June to 9 September 2001. 4. See "The 'Relative' Installation of the Album Panels, Rue Saint-Florentin," in Groom 1993, pp. 3, 84–90, and Groom 2001, p. 131. 5. In Groom's (1993, p. 3) words, "the [Album series] paintings were never intended for 'permanent' installation, but to be moved at whim within the Natansons' city and country residences." 6. For Vuillard's journal entries on the Jardins publics, see Vuillard, Journal, MS. 5396, carnet 2, fols. 66r–67r (January 1894), 44r (16 July 1894), 45r (23 July 1894), 45v (24 July 1894), 46r (27 July 1894), 46v (2 August 1894), 48r (7 August 1894), 48v (21, 30 August 1894), 49r (after 30 August 1894), 50r (10 September 1894). (Vuillard's journal is interrupted in 1895, but where it resumes, in 1907, his daily entries demonstrate that he consistently devotes the same attention to the conception, evolution, and installation of his decorations.) Vuillard's preparatory sketches for the Jardin publics cycle have been discussed by Frèches-Thory (1979, pp. 305–12) and Groom (1993, pp. 59–64). 7. The authors wish to thank Dr. Gabriel Weisberg, as well as an anonymous reader of this article, for suggestions and criticisms which have been incorporated throughout. 8. Vuillard periodically made lists of the most significant events that had shaped his life. Fifteen such outlines—which we have termed autobiographic summaries—are preserved in Vuillard's multi-volume journal manuscript deposited in the library of the Institut de France, MSS. 5396–99. The full citation reads: "30 octobre [1896]. Les évènements les plus capitaux, les idées les plus fécondes sont ceux dont on ne parle pas au jour le jour ainsi que ci-dessus qu'est-ce en comparaison de ce qui vient de se passer—Pour prendre date, septembre [1895] le service de Schopfer, octobre les 28 jours—Nancy.—Ahurissement profond à cette rentrée—Conserver surtout le souvenir qu'un changement de vie amène une vraie régénération cérébrale—novembre les panneaux de Thadée" (Vuillard, Journal, MS. 5396, carnet 2, fol. 57v, 30 October 1896). Vuillard also included the Album panels in two later autobiographic summaries; see Vuillard, Journal, MS. 5396, carnet 2, fol. 78r, ca. 1905, and MS. 5397, carnet 2, fol. 13v, 11–12 November 1908. An incomplete transcription of these two autobiographic summaries appears in Easton 1989, pp. 143–44. 9. "Au centre, un groupe de trois dames sur un canapé considèrent un album ouvert. Une, à droite, dispose des fleurs, deux se groupent à gauche ; la septième est au bord du cadre. . . . Effet général rouge et vert avivé de jaune. Il se ramasse au fond, en taches menues juxtaposées, mais se répand en se nuançant dans le reste de la composition, le rouge descendant jusqu'à des marrons et des noirs, pour monter jusqu'à des vermillons et des roses, le jaune s'éteignant jusqu'au beige. La couleur, tantôt se divise en toutes petites touches, tantôt s'étend en masses à peine nuancées, les deux procédés ne contrastant nulle part plus qu'au centre" (Fénéon in Natanson sale 1908, no. 51; reprinted in Fénéon 1970, p. 258). 10. "Sur une table où traînent des fleurs, des étoffes, des cahiers, des cartons, le pot de grès porte un bouquet épanoui. Quatre dames groupées deux à deux, une assise et trois debout, l'environnent, allant du premier plan de droite au fond de gauche. Presque tous les éléments de couleur des tableaux L'album et La table de toilette" (ibid., no. 52). 11. "Entre deux bouquets et de chaque côté d'une table, deux dames. De l'une ne paraissent que le haut de la tête, une part du corsage et de la jupe avec ses plis et le bras ; de l'autre, que le chignon, le profil perdu, la nuque, le dos et les bras ; ses mains reposent sur un meuble drapé, au premier plan. La nature morte comprend un vase, une boîte, un miroir, des étoffes. Ce qui distingue ici l'aspect général, analogue à celui du L'Album, c'est un gris de deux tons éteints, allié à des roses tendres et des beiges et avivé par des rouges, un accent orangé éclatant, un rouge rehaussé de noir et un accord vert et orange" (ibid., no. 53). 12. "De la main gauche elle coud ses laines sur le canevas tendu ; la droite retient sur son genou un écheveau dont les brins pendent jusqu'aux pelotons de la corbeille. Entre la tisseuse et la fenêtre, dont le rideau est tiré à deux mains par une fillette, un buisson de branches fleuries s'interpose. Face à la jeune femme, une autre enfant dont on ne voit que le buste. Seule particularité, une grande tache noire où se découpe une arabesque rouge vif" (ibid., no. 54). 13. "Deux dames respirent des fleurs disposées en bouquets dans des vases. Un enfant entre, au fond. L'effet général, ici plus ramassé, n'en paraît que plus précieux. L'élément nouveau serait, avec un éclat jaune et rose à droite en haut, une tache tissée de rouge et de beige" (ibid., no. 55; reprinted in Fénéon 1970, p. 259). 14. La lecture (1896, oil on cardboard, formerly Thadée Natanson collection) is described by Fénéon in Natanson sale 1908, no. 47; La conversation (1896, oil on cardboard, Vincent O'Brien, Cashel, Ireland) is reproduced in Burlington Magazine 104, no. 716, (November 1962), ill. p. 71. In 1896 Vuillard spent most of the month of July and, except for a few days, the entire period between 20 October and 20 December with Misia and Thadée Natanson at their country house, La Grangette, on the edge of the Seine in Valvins, not far from Fontainebleau. These extended sojourns, separated by a period of intense productivity back in Paris, were to be Vuillard's first true villégiatures; they initiated a rhythm of alternating city and country existence, a pattern that would become an increasingly vital assurance of regeneration for Vuillard and his art. See Vuillard, Journal, MS. 5396, carnet 2, fols. 57v, 78r. 15. Le déjeuner (1897, oil on cardboard, laid on cradled panel) is reproduced in Groom 2001, p. 134, fig. 1. Le pot de grès is also seen hanging in the dining room of the rue Saint-Florentin apartment in Misia et Vallotton (1898, oil on board, William Kelly Simpson, New York); reproduced in Groom 1993, p. 86, fig. 144. For a photograph taken by Vuillard of Misia standing next to La tapisserie, see Bernier 1983, p. 13; reproduced in Groom 2001, p. 131, fig. 1. Other, unpublished, photographs of the Natanson dining room by Vuillard are in the Archives Salomon, Paris. 16. One of Vuillard's photographs of the Natanson billiard room at Villeneuve is published in Bernier 1983, p. 9; reproduced in Groom 2001, p. 131, fig. 2. L'album is seen hanging at the back of the room; Le pot de grès is barely visible at right. Another, unpublished, photograph in the Archives Salomon, Paris, confirms the identification of Le pot de grès as being the second picture in the billiard room. 17. See "The 'Relative' Installation of the Album Panels, Rue Saint-Florentin," in Groom 1993, pp. 84–90. Groom's thesis is repeated in Groom 2001, pp. 126–31. 18. Writing for the Revue blanche in 1896 on Vuillard's recently completed decorations for Dr. Vaquez (1896, Petit Palais, Paris), Thadée recalls earlier decorations by Vuillard including his own: "On a pu voir à l'Art Nouveau un autre ensemble de panneaux décoratifs diaprés de femmes et de fleurs" (T. Natanson, "Peinture," La Revue blanche 11, no. 84 [1 December 1896], p. 518). While Thadée refers to his cycle in passing, Groom (1993, p. 76), who misdates the reference to February 1897, has erroneously interpreted the remainder of the passage, actually a description of the Vaquez panels, as a description of the Album panels. Bareau (1986, p. 44, nn. 4, 5) also misdates Thadée Natanson's article as 1 June 1896. 19. For the transformation of Bing's townhouse into the Maison de l'Art Nouveau by the French architect Louis Bonnier, see Weisberg 1982, pp. 241–49; "The Creation of L'Art Nouveau," in Weisberg 1986, pp. 46–95; Marrey 1988, pp. 31–41, 167–82. 20. "L'ART-NOUVEAU a pour but de grouper parmi les manifestations artistiques toutes celles qui cessent d'être la réincarnation du passé—d'offrir, sans exclusion de catégories et sans préférence d'Ecole, un lieu de concentration à toutes les oeuvres marquées d'un sentiment nettement personnel. 21. Salon de l'Art Nouveau, Premier catalogue (Paris, 1895), no. 210. Vuillard also exhibited an important painted porcelain dinner service commissioned by Jean Schopfer, although the service does not appear in the catalogue. See Schopfer 1897, pp. 252–55. For a period photograph of Vuillard's plates as they were displayed in Henry Van de Velde's dining room at the Salon de l'Art Nouveau, see Weisberg 1986, pl. 57. For color reproductions of several plates from the service, see Weisberg 1986, pls. 17–19; Frèches-Thory and Terrasse 1990, p. 192; and Troy 1991, pl. 3. 22. A convert to avant-garde painting, Le Barc de Boutteville owned a gallery on the rue le Pelletier that became a veritable showcase for the Nabis, offering regular exhibitions of their work from 1891 until 1896. Albert Aurier, writing for the Mercure de France in 1892, described Le Barc's efforts as follows: "Avoir délibérément offert aux jeunes artistes novateurs, encore contestés par la critique et dédainés par les chalands et généralement bafoués par les marchands et les jurys, un asile permanent où ils puissent exposer au jugement du public, sans craindre de trop infamantes promiscuités, les résultats de leurs travaux et de leurs recherches, c'est assurément une belle et généreuse idée" (G.-Albert Aurier, "Deux Expositions: Berthe Morisot; Deuxième exposition des peintres impressionnistes et symbolistes," Mercure de France 5, no. 30 [June 1892], p. 166). 23. ". . . M. Bing s'était adressé aux deux jeunes gens dont on vantait le plus les qualités décoratives, M. Vuillard et M. Denis, et il leur avait donnés un salon et une chambre à coucher à orner. M. Vuillard, dont j'ai parlé souvent avec sympathie et dont l'on sait d'exquises petites toiles japonisantes, a envoyés quelques panneaux qui ne se lient à rien, qui n'ont pas de sens relativement aux éclairages de la pièce, et qui rééditent, en un empâtement de taches disgracieuses, un motif banal de femmes émergeant de fouillis de fleurs sans caractère" (Camille Mauclair, "Choses d'art," Mercure de France 17, no. 74 [February 1896], pp. 267–68). For a discussion of Mauclair's strange and damaging turnabout with regard to the Nabis, see Mauner (1967) 1978, pp. 137–40. Camille Pissarro referred to the Vuillards exhibited at Bing's as a "disaster." See Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, 30 September 1896, in Correspondance, edited by Janine Bailly-Herzberg, vol. 4 (Paris: Valhermeil, 1989), no. 1305. 24. "Des travaux à exécuter pour l'exposition "L'Art Nouveau", il me réservait la part du lion : une salle à manger en cèdre incrusté de cuivre rouge, un fumoir en padouk congolais avec des panneaux en mosaïque de verre, un cabinet de collectionneur et une rotonde dont les lambris en bois de citronnier encadreraient de fades et élégants panneaux de Besnard. Il confierait l'exécution de la décoration murale de la salle à manger au peintre Ranson, au peintre Besnard celle du salon et, au vingtiste Georges Lemmen, des panneaux de céramique ou de mosaïque et des tapis. Au peintre Maurice Denis, Bing commanderait la réalisation du mobilier et de la décoration d'une chambre à coucher ; à l'artiste anglais Charles Conder, l'ensemble d'un boudoir. Une antechambre serait décorée par Vuillard et, pour le restant, le programme était encore à l'étude, Bing comptait inaugurer L'Art Nouveau au mois d'octobre prochain." See Van de Velde 1992, pp. 267–68. 25. The passage reads: "La migraine commence à me gagner, l'énervement me court au bout des doigts, je suis à point pour goûter l'Art nouveau. Dans une rotonde je vois un plafond ravissant et des paysages diaprés de M. Besnard, l'homme qui a su, de notre temps, mettre sa verve et sa virtuosité surprenantes, le plus audacieusement, au service de nos mauvais instincts. C'est un corrupteur de premier ordre ; mais nous le savions. Dans une pièce contiguë, ce sont des panneaux harmonieux et discrets de M. Vuillard, mais éclairés par un lustre absurde où de grosses mouches tournoient en nous éclairant avec leur derrière transparent "(A. Alexandre, "L'Art Nouveau," Le Figaro, 28 December 1895, p. 1). 26. ". . . descendons [from the upper floor] au salon en rotonde décoré par M. Besnard. Une antichambre le précède où des panneaux de M. Édouard Vuillard mettent en scène des femmes d'intérieur. Du plafond pend un lustre de M. Pierre Roche. M. Vuillard est un harmoniste rare; il sent le charme de l'intimité, l'énigme où semble vivre tout être solitaire. Il vocalise en mineur; ses tons sont neutres et sourds, ses combinaisons subtiles" (E. Cousturier, "Galeries S. Bing: Le mobilier," La revue blanche 10, no. 63 [5 January 1896], p. 93). The hanging lamp by Pierre Roche is number 596 in the Salon de l'Art Nouveau exhibition catalogue: "Lucioles, pour éclairage électrique." 27. This floor plan has been published by Weisberg (1986, p. 52, fig. 36). 28. The authors regret that they were unable to obtain a reproduction of this important document from the Salomon Archives. 29. Édouard Vuillard, project sketch for the Album series, 1895, pen and india ink, pastel on paper (20.2 x 31 cm), Archives Salomon, Paris. In her important article on the reconstruction of the Jardins publics series, Frèches-Thory (1979, pp. 307–9, figs. 2, 3) published two pastel sketches by Vuillard similar in style and purpose to the project sketch for the Album series. These drawings, today in the collection of the Musée d'Orsay, originally belonged to the Archives Salomon and are repoduced in Groom 1993, figs. 101, 102. 30. Groom (1993, p. 69) suggests that in choosing such unusual and varying formats for the Album panels Vuillard may have wished to evoke the idea of an album or portfolio: "His choices of format and loosely connected themes may have been intended to resemble a portfolio arrangement, wherein individual prints with a general rather than specific connection are brought together." 31. T. Natanson, "'Art Nouveau,'" La revue blanche 10, no. 64 (1 February 1896), pp. 115–17. Thadée Natanson's enthusiasm for Bing's Art Nouveau also resulted in his important patronage of Henry Van de Velde. Van de Velde, who had arrived in Paris in December 1895 to oversee the installation of his model rooms for L'Art Nouveau exhibition, records dining at the Natansons on 20 December with Toulouse-Lautrec, Vallotton, Bonnard and Vuillard. On 28 December, Van de Velde was again invited to dinner and in the course of the evening Misia commissioned a bedroom from him. Finally, in 1899, Thadée engaged Van de Velde to redesign four rooms at the offices of the Revue blanche. See Van de Velde 1992, pp. 279, n. 3, 305, n. 7, 405, 411. On Bing and Maurice Denis, see Weisberg 1986, pp. 67, 273, n. 26. 32. Fénéon, in his catalogue entries for Thadée's auction of 1908, presents the Album panels in a different order than that which we have proposed above. He may have never registered, or perhaps had by now forgotten the original disposition of the panels at Bing's Art Nouveau. In any event, with a public auction the priorities would have changed: since the ensemble was now being broken up and dispersed, it would not have been in the interest of the sale to emphasize the decoration's original unity and sequential order. The auction catalogue logically began with the most important picture (L'album [fig. 2]), followed by the two horizontal pendants (Le pot de grès [fig. 5] and La table de toilette [fig. 4]), then La tapisserie (fig. 3), and finally the smallest picture Le corsage rayé (fig. 1). See notes 9–13 above. 33. See note 25 above. 34. The windows were in fact blacked out in Henry Van de Velde's "back room," located on the upper floor, directly above Vuillard's antechamber. See Weisberg 1986, fig. 57. 35. "C'est à propos de cette peinture et de l'ensemble auquel elle appartient, qu'on pourrait faire une observation qui s'applique, moins qu'elle ne s'appliquait, mais s'applique aux oeuvres de l'auteur et de meilleurs parmi ses contemporains ; savoir : le dessin, ou la détermination des objets, n'a dans les tableaux que sa valeur plastique d'arabesque. Le plaisir de nommer les objets intervient sans doute dans celui que donnent les images, mais il n'en est pas l'essentiel, qui est abstrait" (Fénéon in Natanson sale 1908, no. 51). 36. "Vuillard, dont le raffinement me paraît le plus directement, le plus voluptueusement sensuel, me paraît aussi le plus impassible parmi la tendresse ou l'acuité des sensations qu'il évoque courageusement dans leur complexité. Sa volonté n'intervient dans le ragoût de ses combinaisons que pour marquer sa personnalité. Son unique souci est délibérément abstrait. Il semble demeurer d'autant plus abstrait d'intention qu'il est plus délicieusement, plus somptueusement sensuel. Si sa sensibilité a quelque chose d'enivrant, il est assez subtil et ingénieux pour la maintenir toujours savamment en équilibre. J'ajoute qu'il n'est jamais plus à l'aise et qu'on ne le goûte jamais mieux que quand son imagination—je la voudrais dire musicale—peut se donner carrière sur d'assez amples surfaces : il faut des murs à sa magie." O. Mirbeau, "Préface," in Natanson sale 1908, p. xv. 37. La dame en bleu is reproduced in Thomson 1988, colorpl. 9; Autoportrait: Vuillard décorateur is reproduced in ibid., p. 32, pl. 18. In these and other paintings datable to 1894, Vuillard renounces the brilliant counterpoint of his 1893 pictures—the virtuoso spatial manipulations, the seemingly unlimited juxtapositions, alternations, and interplays of opposing pictorial elements—in favor of interjecting a single, enlivening dissonance into a unified field of general accord. 38. This valid tendency has nevertheless led more than one writer astray. In a chapter of her exhibition catalogue entitled "The Music of Painting: Homages to Misia," Easton based a discussion of Vuillard and the Symbolist doctrine of synaesthesia on a brief text jotted down by Vuillard on a loose scrap of paper. This piece of paper, which was tucked into Vuillard's journal at some uncertain date, reads as follows: "L'impression qu'on reçoit par les beaux-arts n'a pas le moindre rapport avec le plaisir que fait éprouver une imitation quelconque. Qui dit un art dit une poésie. Il n'y a pas d'art sans un but poétique. Il y a un genre d'émotion qui est tout particulier à la peinture. Il y a une impression qui résulte de tel arrangement de couleurs, de lumières, d'ombres, etc. C'est ce qu'on appellerait la musique du tableau." Although there is little doubt that Vuillard shared the sentiment expressed in this passage, he is not, as Easton (1989, p. 105) believes, its author. These lines were in fact written by Eugène Delacroix and published in Oeuvres littéraires, vol. 1, Études esthétiques, Bibliothèque dionysienne (Paris: G. Crès, 1923), pp. 66, 63. Vuillard owned a copy of the 1923 edition of Oeuvres littéraires and therefore Vuillard most likely copied out Delacroix's lines some time after 1923, not in January 1894 as Easton implies. 39. See note 23 above. 40. See note 35 above. 41. See Groom 2001, p. 99, for a reproduction of the original state of Denis's bedroom frieze. For a reproduction of Ranson's dining room murals, see Weisberg 1996, p. 69, fig. 57. Writing on the Van de Velde / Ranson dining room, Nancy Troy (1991, p. 24) has identified the arabesque—abstractly symbolized by the inlayed red copper motifs of Van de Velde's wainscoting—as the unifying theme for the entire room. 42. Cited in translation in Weisberg 1996, p. 56. Weisberg misread the date of this letter as 30 April 1895. See Thérèse Barruel, "Decorations for the Bedroom of a Young Girl, 1895–1900," in Groom 2001, pp. 262–63, n. 6. From the tone of Bing's letter it seems highly unlikely that he would have allowed Vuillard to decorate his antechamber with disjointed panels conceived to decorate a nonspecific interior with no particular function. On the other hand, Bing's stipulation that the Nabis rooms create a harmonious whole may have stimulated the artists to invent complementary and interrelated themes. Vuillard's young bourgeois women engaged in interior domestic activities nicely complements Ranson's young peasant women laboring out of doors in fields. And Denis's The Love and Life of a Woman may have been intended as a kind of transcendent and unifying theme, tracing a woman's symbolic, visionary voyage from girlhood to motherhood. The relative homogeneity of the Nabis model rooms is exceptional in the context of Bing's exhibition, where stylistic variety and overall heterogeneity of artistic expression were the rule. See Watkins 2001, p. 15. 43. Vuillard to Maurice Denis, 30 May 1894; excerpted and translated in Weisberg 1986, p. 49. 44. Weisberg 1986, pp. 49–50. 45. "Lundi matin Bonnard affairé par Bing, Viau, Hoentschel . . . l'après-midi . . . pris Bonnard qui avait touché le matin chez Bing avec Kerr et Ranson (hist. d'Ibels)"; Vuillard, Journal, MS. 5396, carnet 2, fol. 53r, 4 November 1894. 46. Although some of these stained-glass windows are still preserved, only the cartoon for Vuillard's Marronniers survives. In Vuillard's aerial view of a city square, more than half of the composition is given over to decorative patterns suggested by intervening horse chestnut boughs, whose ocher highlights are an idealization of the rusting tendency of horse chestnut leaves at summer's end. The overall flatness of the design is interrupted only by the presence of a building at upper left seen in two-point perspective. For color illustrations of Tiffany's stained-glass windows after cartoons by Toulouse-Lautrec (Musée d'Orsay, Paris) and Roussel (private collection), see Frèches-Thory and Terrasse 1990, pp. 185, 189. 47. Seven windows were shown at the Salon de l'Art Nouveau: those after cartoons by Bonnard, Ibels, Ranson, Roussel, Toulouse-Lautrec, Vallotton, and Vuillard. For a discussion of the critical reception of Tiffany's windows in France, see ibid., pp. 182–90. 48. Mauner (1967) 1978, p. 161. 49. Roger-Marx 1946b, pp. 53–54. For the original French text, see Roger-Marx 1946a, p. 54. 50. For Maurice Denis on Redon, see, "Quelques notices, IV: Exposition Odilon Redon" (1903) and "Cézanne" (1907), both reprinted in Denis 1913, pp. 132–34, 245–46; "L'époque du symbolisme" (February 1934), reprinted in Gazette des Beaux-Arts 76, no. 854 (March 1934), pp. 165–79. See also "Hommage à Odilon Redon," La vie, 30 November and 7 December 1912, with important testimonials by Bonnard, Denis, Mellerio, Sérusier, and others. 51. "Parmi les annonciateurs de la bonne parole, qu'aiment à invoquer les jeunes, un autre artiste aussi original, aussi profondement idéaliste, encore plus étrange et plus terrifiant, qui, par son hautain mépris de l'imitation matérielle, par son amour du rêve et de la spiritualité dut agir, sinon aussi immédiatement que les précédents, du moins par contre-coup, sur l'orientation des neuves âmes d'artistes d'aujourd'hui: Odilon Redon"; G.-Albert Aurier, "Les peintres symbolistes," Revue encyclopédique 2, no. 32 (1 April 1892), pp. 474–86. 52. "Plus profondément que dans la jouissance qu'est le souvenir de nos sensations, la pensée se complaît encore à baigner dans une atmosphère imprécise où sa fantaisie peut se jouer librement et qui l'enivre : le rêve—. . . c'est lui qui consacre les poètes et sa qualité qui fait la qualité de leurs oeuvres. Cette fois il est toute l'inspiration d'un art plastique"; Thadée Natanson, "Expositions," La revue blanche 6, no. 31 (May 1894), pp. 470–71. 53. "Les blancs poudroient, frémissent, lueurs, vapeurs, éclats, reflets, frissons, diaprures, ajoutant à la magie des noirs, et s'ils ne les créent, achèvent leur splendeur, font miroiter l'essence de leur velours, et reculer jusqu'au miracle leurs ténèbres absolues"; Thadée Natanson, "Petite Gazette d'art," La revue blanche 12, no. 88 (1 Feb. 1897), p. 140. 54. "M. Odilon Redon a appris aux jeunes qui l'entourent quelles libertés autorise le don, permis d'approfondir les ressources de leur métier par l'usage de la lithographie. Il a au plus haut point ces dons plastiques primordiaux dont ils ont avant tout le souci et le respect. Voilà qui donne un sens profond à sa présence"; Thadée Natanson, "Une date de l'histoire de la peinture française: Mars 1899," La revue blanche 19, no. 148 (1 Aug. 1899), pp. 505–6. 55. A letter from a certain E. Castillond, dated 13 January 1893 and addressed to Vuillard, proposes the sale of a Redon album (Salomon Archives, Paris). 56. See, for example, Vuillard's lithographs in Roger-Marx 1948, nos. 18, 21, 22. 57. Vuillard uses the words "observable and verifiable" in a journal entry from January 1894 (MS. 5396, carnet 2, fol. 66r). 58. See also Vuillard's Intimité (Roger-Marx 1948, no. 10), a lithograph dating to about 1895, in which Misia and Thadée are seen in their salon. 59. See Groom 1993, p. 80. 60. "Outre les admirables lithographies noires et quelques-unes des feuilles des inoubliables Albums, ce sont les pastels et les peintures qui ont fait la nouveauté et la rareté du spectacle. Sans doute l'oeil émerveillé avait comme entrevu déjà l'éclat des couleurs dans l'intensité de ses noirs. Mais jamais il n'en avait eu la joie complète. Le peintre comme le lithographe s'affirme Prince du Rêve"; Thadée Natanson, "Expositions," La revue blanche 8, no. 47 (15 May 1894), p. 470. 61. According to records preserved in the Salomon Archives in Paris, Vuillard owned two important Redon flower compositions—a painting and a pastel—as well as a coastal scene, all dating to after 1900. 62. On Vuillard's one-man show, Hermann (1959, p. 433) notes beside the year 1891 in his chronology of events from Vuillard's Nabi years: "Kleine Ausstellung in den Räumen der 'Revue blanche.'" Although there seems to have been no catalogue for this exhibition, Fénéon (1970, p. 454) confirms that it did take place: "La revue abrita dans son local exigu de la rue des Martyrs la première exposition de Vuillard." La revue blanche moved its offices to the rue des Martyrs during the summer of 1891; publication of the review was suspended between June and October. See Mauner (1967) 1978, p. 75, for a letter written by Paul Ranson to Jan Verkade in November 1891 concerning a possible Nabi group exhibition to be held in the offices of the Revue blanche: "on nous demande d'exposer à la Revue blanche." |